Association Between Unmet Healthcare Needs and Depression in Older Adults: Evidence from the Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

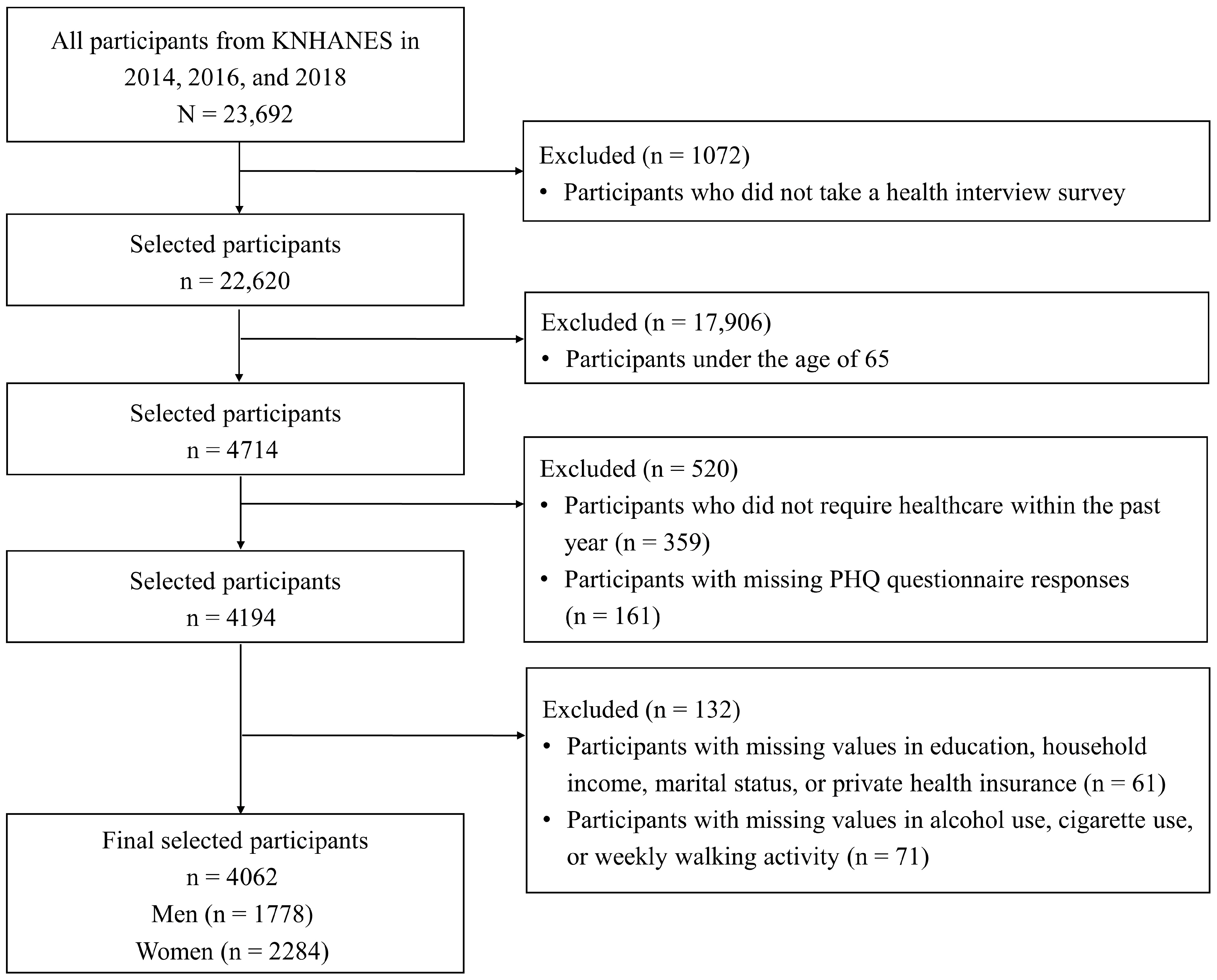

2.1. Data Sources and Study Participants

2.2. Assessment of Depressive Symptoms

2.3. Assessment of Unmet Healthcare Needs

2.4. Assessment of Covariates

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. General Participant Characteristics Between the Non-Depression and Depression Groups

3.2. Participant Characteristics by Met and Unmet Healthcare Needs

3.3. Association Between Unmet Healthcare Needs and Depression

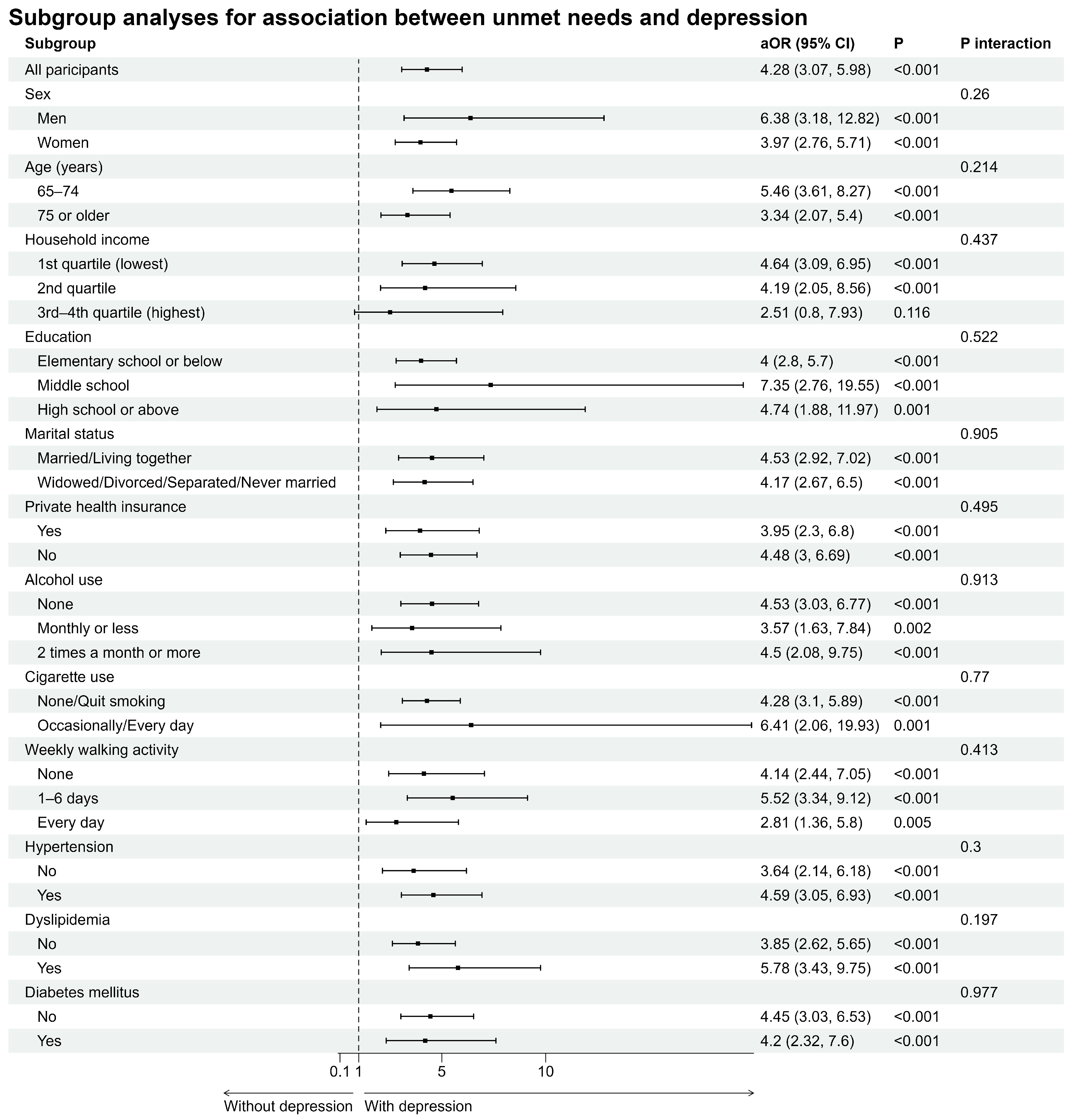

3.4. Association Between Unmet Healthcare Needs and Depression Stratified by Subgroups

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| aOR | Adjusted Odds Ratio |

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

| KNHANES | Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey |

| OR | Odds Ratio |

| PHQ-9 | Patient Health Questionnaire-9 |

| uOR | Unadjusted Odds Ratio |

References

- Saito, K. Solving the “super-ageing” challenge. In Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development; The OECD Observer: Paris, France, 2014; Volume 49. [Google Scholar]

- Aziz, R.; Steffens, D.C. What are the causes of late-life depression? Psychiatr. Clin. N. Am. 2013, 36, 497–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blazer, D.G.; Hybels, C.F. Origins of depression in later life. Psychol. Med. 2005, 35, 1241–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tiemeier, H. Biological risk factors for late life depression. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2003, 18, 745–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, M.; Unützer, J. Geriatric depression in primary care. Psychiatr. Clin. N. Am. 2011, 34, 469–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obuobi-Donkor, G.; Nkire, N.; Agyapong, V.I. Prevalence of major depressive disorder and correlates of thoughts of death, suicidal behaviour, and death by suicide in the geriatric population—A general review of literature. Behav. Sci. 2021, 11, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prigge, R.; Wild, S.H.; Jackson, C.A. Depression, diabetes, comorbid depression and diabetes and risk of all-cause and cause-specific mortality: A prospective cohort study. Diabetologia 2022, 65, 1450–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Ma, L. Depression and cardiovascular disease in elderly: Current understanding. J. Clin. Neurosci. 2018, 47, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdoli, N.; Salari, N.; Darvishi, N.; Jafarpour, S.; Solaymani, M.; Mohammadi, M.; Shohaimi, S. The global prevalence of major depressive disorder (MDD) among the elderly: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2022, 132, 1067–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, T.; Zhao, X.; Wu, M.; Li, Z.; Luo, L.; Yang, C.; Yang, F. Prevalence of depression in older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2022, 311, 114511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasin, D.S.; Goodwin, R.D.; Stinson, F.S.; Grant, B.F. Epidemiology of major depressive disorder: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcoholism and Related Conditions. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2005, 62, 1097–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Wu, X.; Tang, M.; Shi, L.; Gong, S.; Mei, X.; Zhao, Z.; He, J.; Huang, L.; Cui, W. Late-life depression: Epidemiology, phenotype, pathogenesis and treatment before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Front. Psychiatry 2023, 14, 1017203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schoevers, R.; Beekman, A.; Deeg, D.; Geerlings, M.; Jonker, C.; Van Tilburg, W. Risk factors for depression in later life; results of a prospective community based study (AMSTEL). J. Affect. Disord. 2000, 59, 127–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borges, L.J.; Benedetti, T.R.B.; Xavier, A.J.; d’Orsi, E. Associated factors of depressive symptoms in the elderly: EpiFloripa study. Rev. Saude Publica 2013, 47, 701–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasiliu, O.; Vasile, D. Risk factors and quality of life in late-life depressive disorders. Rom. J. Mil. Med. 2016, 119, 24–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Areán, P.A.; Reynolds, C.F., III. The impact of psychosocial factors on late-life depression. Biol. Psychiatry 2005, 58, 277–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, O.P.; Pirkis, J.; Kerse, N.; Sim, M.; Flicker, L.; Snowdon, J.; Draper, B.; Byrne, G.; Lautenschlager, N.T.; Stocks, N. Socioeconomic disadvantage increases risk of prevalent and persistent depression in later life. J. Affect. Disord. 2012, 138, 322–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mezuk, B.; Rafferty, J.A.; Kershaw, K.N.; Hudson, D.; Abdou, C.M.; Lee, H.; Eaton, W.W.; Jackson, J.S. Reconsidering the role of social disadvantage in physical and mental health: Stressful life events, health behaviors, race, and depression. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2010, 172, 1238–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalánková, D.; Stolt, M.; Scott, P.A.; Papastavrou, E.; Suhonen, R.; on behalf of the RANCARE COST Action CA15208. Unmet care needs of older people: A scoping review. Nurs. Ethics 2021, 28, 149–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, J.; Pabst, A.; Weyerer, S.; Werle, J.; Maier, W.; Heilmann, K.; Scherer, M.; Stark, A.; Kaduszkiewicz, H.; Wiese, B. The assessment of met and unmet care needs in the oldest old with and without depression using the Camberwell Assessment of Need for the Elderly (CANE): Results of the AgeMooDe study. J. Affect. Disord. 2016, 193, 309–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, Y.S.; Jung, B.; Kim, D.; Ha, I.-H. Factors underlying unmet medical needs: A cross-sectional study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, B.; Wang, J. Unmet long-term care needs and depression: The double disadvantage of community-dwelling older people in rural China. Health Soc. Care Community 2019, 27, 126–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacLeod, S.; Musich, S.; Gulyas, S.; Cheng, Y.; Tkatch, R.; Cempellin, D.; Bhattarai, G.R.; Hawkins, K.; Yeh, C.S. The impact of inadequate health literacy on patient satisfaction, healthcare utilization, and expenditures among older adults. Geriatr. Nurs. 2017, 38, 334–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sari, N. Exercise, physical activity and healthcare utilization: A review of literature for older adults. Maturitas 2011, 70, 285–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valtorta, N.K.; Moore, D.C.; Barron, L.; Stow, D.; Hanratty, B. Older adults’ social relationships and health care utilization: A systematic review. Am. J. Public Health 2018, 108, e1–e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, X.; An, R.; Heinemann, A. Depression and unmet needs for assistance with daily activities among community-dwelling older adults. Gerontologist 2018, 58, 428–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alltag, S.; Stein, J.; Pabst, A.; Weyerer, S.; Werle, J.; Maier, W.; Miebach, L.; Scherer, M.; Stark, A.; Wiese, B. Unmet needs in the depressed primary care elderly and their relation to severity of depression: Results from the AgeMooDe study. Aging Ment. Health 2018, 22, 1038–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zuverink, A.; Xiang, X. Anxiety and unmet needs for assistance with daily activities among older adults. J. Aging Health 2020, 32, 491–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herr, M.; Arvieu, J.-J.; Aegerter, P.; Robine, J.-M.; Ankri, J. Unmet health care needs of older people: Prevalence and predictors in a French cross-sectional survey. Eur. J. Public Health 2014, 24, 808–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Q.; Prina, M.; Wu, Y.-T.; Mayston, R. Unmet healthcare needs among middle-aged and older adults in China. Age Ageing 2022, 51, afab235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.-S.; Lee, J.; Moon, Y.; Kim, K.J.; Lee, K.; Choi, J.; Han, S.-H. Unmet healthcare needs of elderly people in Korea. BMC Geriatr. 2018, 18, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eimontas, J.; Gegieckaitė, G.; Zamalijeva, O.; Pakalniškienė, V. Unmet healthcare needs predict depression symptoms among older adults. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 8892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, N.G.; McDougall, G. Unmet needs and depressive symptoms among low-income older adults. J. Gerontol. Soc. Work. 2009, 52, 567–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clignet, F.; Houtjes, W.; van Straten, A.; Cuijpers, P.; van Meijel, B. Unmet care needs, care provision and patient satisfaction in patients with a late life depression: A cross-sectional study. Aging Ment. Health 2019, 23, 491–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, J.; Liegert, P.; Dorow, M.; König, H.-H.; Riedel-Heller, S.G. Unmet health care needs in old age and their association with depression–results of a population-representative survey. J. Affect. Disord. 2019, 245, 998–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, S.A.; Safian, N.; Ahmad, S.; Nurumal, S.R.; Mohammad, Z.; Mansor, J.; Wan Ibadullah, W.A.H.; Shobugawa, Y.; Rosenberg, M. Unmet healthcare needs among elderly Malaysians. J. Multidiscip. Healthc. 2021, 14, 2931–2940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kweon, S.; Kim, Y.; Jang, M.-j.; Kim, Y.; Kim, K.; Choi, S.; Chun, C.; Khang, Y.-H.; Oh, K. Data resource profile: The Korea national health and nutrition examination survey (KNHANES). Int. J. Epidemiol. 2014, 43, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oh, K.; Kim, Y.; Kweon, S.; Kim, S.; Yun, S.; Park, S.; Lee, Y.-K.; Kim, Y.; Park, O.; Jeong, E.K. Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 20th anniversary: Accomplishments and future directions. Epidemiol. Health 2021, 43, e2021025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroenke, K.; Spitzer, R.L.; Williams, J.B. The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2001, 16, 606–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manea, L.; Gilbody, S.; McMillan, D. Optimal cut-off score for diagnosing depression with the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9): A meta-analysis. CMAJ 2012, 184, E191–E196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scott, A. Rao-Scott corrections and their impact. In Proceedings of the 2007 Joint Statistical Meetings, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 29 July–2 August 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Charlson, M.; Peterson, J.C. Medical comorbidity and late life depression: What is known and what are the unmet needs? Biol. Psychiatry 2002, 52, 226–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simsek, H.; Erkoyun, E.; Akoz, A.; Ergor, A.; Ucku, R. Unmet health and social care needs and associated factors among older people aged ≥80 years in Izmir, Turkey. East. Mediterr. Health J. 2021, 27, 772–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Liu, Q.; Fu, R.; Ma, J. Unmet healthcare needs, health outcomes, and health inequalities among older people in China. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1082517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ettman, C.K.; Subramanian, M.; Fan, A.Y.; Adam, G.P.; Abdalla, S.M.; Galea, S.; Stuart, E.A. Assets and depression in US adults during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2024, 59, 571–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.; Rosenblat, J.D.; Brietzke, E.; Pan, Z.; Lee, Y.; Cao, B.; Zuckerman, H.; Kalantarova, A.; McIntyre, R.S. Stress, epigenetics and depression: A systematic review. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2019, 102, 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assari, S. High income protects whites but not African Americans against risk of depression. Healthcare 2018, 6, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fiske, A.; Wetherell, J.L.; Gatz, M. Depression in older adults. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2009, 5, 363–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ettman, C.K.; Thornburg, B.; Abdalla, S.M.; Meiselbach, M.K.; Galea, S. Financial assets and mental health over time. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 27370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ettman, C.K.; Abdalla, S.M.; Cohen, G.H.; Sampson, L.; Vivier, P.M.; Galea, S. Low assets and financial stressors associated with higher depression during COVID-19 in a nationally representative sample of US adults. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2021, 75, 501–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ettman, C.K.; Fan, A.Y.; Philips, A.P.; Adam, G.P.; Ringlein, G.; Clark, M.A.; Wilson, I.B.; Vivier, P.M.; Galea, S. Financial strain and depression in the US: A scoping review. Transl. Psychiatry 2023, 13, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Overall | Non-Depression | Depression | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of participants | 4062 | 3749 | 313 | |

| Unmet needs | <0.001 | |||

| No | 3624 (89.14) | 3415 (91.15) | 209 (63.82) | |

| Yes | 438 (10.86) | 334 (8.85) | 104 (36.18) | |

| Sex | <0.001 | |||

| Men | 1778 (42.89) | 1704 (44.63) | 74 (21.02) | |

| Women | 2284 (57.11) | 2045 (55.37) | 239 (78.98) | |

| Age (years) | 0.256 | |||

| 65–74 | 2541 (60.74) | 2355 (61.02) | 186 (57.21) | |

| ≥75 | 1521 (39.26) | 1394 (38.98) | 127 (42.79) | |

| Household income | <0.001 | |||

| 1st quartile (lowest) | 1916 (47.11) | 1705 (45.51) | 211 (67.22) | |

| 2nd quartile | 1089 (26.14) | 1017 (26.37) | 72 (23.18) | |

| 3rd- 4th quartile (highest) | 1057 (26.76) | 1027 (28.12) | 30 (9.6) | |

| Education | <0.001 | |||

| Elementary school or below | 2360 (57.69) | 2120 (56.15) | 240 (77.02) | |

| Middle school | 623 (15.21) | 587 (15.5) | 36 (11.58) | |

| High school or above | 1079 (27.1) | 1042 (28.35) | 37 (11.4) | |

| Marital status | <0.001 | |||

| Married/Living together | 2755 (65.54) | 2594 (67.07) | 161 (46.35) | |

| Widowed/Divorced/Separated/Never married | 1307 (34.46) | 1155 (32.93) | 152 (53.65) | |

| Private health insurance | <0.001 | |||

| Yes | 1677 (42.25) | 1581 (43.2) | 96 (30.26) | |

| No | 2385 (57.75) | 2168 (56.8) | 217 (69.74) | |

| Alcohol use | <0.001 | |||

| None | 1970 (48.41) | 1776 (47.22) | 194 (63.38) | |

| Monthly or less | 931 (22.92) | 877 (23.42) | 54 (16.63) | |

| 2 times a month or more | 1161 (28.67) | 1096 (29.36) | 65 (19.99) | |

| Cigarette use | 0.842 | |||

| None/Quit smoking | 3684 (90.93) | 3400 (90.96) | 284 (90.56) | |

| Occasionally/Every day | 378 (9.07) | 349 (9.04) | 29 (9.44) | |

| Weekly walking activity | <0.001 | |||

| None | 1089 (26.14) | 956 (24.68) | 133 (44.42) | |

| 1–6 days | 1720 (41.98) | 1613 (42.66) | 107 (33.49) | |

| Every day | 1253 (31.88) | 1180 (32.66) | 73 (22.09) | |

| Hypertension | 0.064 | |||

| No | 1879 (46.03) | 1750 (46.47) | 129 (40.44) | |

| Yes | 2183 (53.97) | 1999 (53.53) | 184 (59.56) | |

| Dyslipidemia | 0.003 | |||

| No | 2994 (74.06) | 2786 (74.75) | 208 (65.48) | |

| Yes | 1068 (25.94) | 963 (25.25) | 105 (34.52) | |

| Diabetes mellitus | 0.006 | |||

| No | 3203 (78.88) | 2977 (79.52) | 226 (70.89) | |

| Yes | 859 (21.12) | 772 (20.48) | 87 (29.11) |

| Variables | Overall | Met Needs | Unmet Needs | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of participants | 4062 | 3624 | 438 | |

| Depression | <0.001 | |||

| No | 3749 (92.63) | 3415 (94.72) | 334 (75.45) | |

| Yes | 313 (7.37) | 209 (5.28) | 104 (24.55) | |

| Sex | <0.001 | |||

| Men | 1778 (42.89) | 1667 (45.11) | 111 (24.72) | |

| Women | 2284 (57.11) | 1957 (54.89) | 327 (75.28) | |

| Age (years) | 0.101 | |||

| 65–74 | 2541 (60.74) | 2286 (61.34) | 255 (55.79) | |

| ≥75 | 1521 (39.26) | 1338 (38.66) | 183 (44.21) | |

| Household income | <0.001 | |||

| 1st quartile (lowest) | 1916 (47.11) | 1650 (45.51) | 266 (60.2) | |

| 2nd quartile | 1089 (26.14) | 988 (26.41) | 101 (23.88) | |

| 3rd–4th quartile (highest) | 1057 (26.76) | 986 (28.08) | 71 (15.93) | |

| Education | <0.001 | |||

| Elementary school or below | 2360 (57.69) | 2030 (55.56) | 330 (75.14) | |

| Middle school | 623 (15.21) | 572 (15.65) | 51 (11.59) | |

| High school or above | 1079 (27.1) | 1022 (28.79) | 57 (13.26) | |

| Marital status | <0.001 | |||

| Married/Living together | 2755 (65.54) | 2517 (67.34) | 238 (50.79) | |

| Widowed/Divorced/Separated/Never married | 1307 (34.46) | 1107 (32.66) | 200 (49.21) | |

| Private health insurance | 0.018 | |||

| Yes | 1677 (42.25) | 1521 (43) | 156 (36.1) | |

| No | 2385 (57.75) | 2103 (57) | 282 (63.9) | |

| Alcohol use | 0.002 | |||

| None | 1970 (48.41) | 1724 (47.63) | 246 (54.79) | |

| Monthly or less | 931 (22.92) | 828 (22.7) | 103 (24.75) | |

| 2 times a month or more | 1161 (28.67) | 1072 (29.67) | 89 (20.46) | |

| Cigarette use | 0.553 | |||

| None/Quit smoking | 3684 (90.93) | 3285 (90.83) | 399 (91.78) | |

| Occasionally/Every day | 378 (9.07) | 339 (9.17) | 39 (8.22) | |

| Weekly walking activity | <0.001 | |||

| None | 1089 (26.14) | 923 (24.81) | 166 (37.08) | |

| 1–6 days | 1720 (41.98) | 1545 (42.28) | 175 (39.57) | |

| Every day | 1253 (31.88) | 1156 (32.92) | 97 (23.35) | |

| Hypertension | 0.417 | |||

| No | 1879 (46.03) | 1692 (46.3) | 187 (43.82) | |

| Yes | 2183 (53.97) | 1932 (53.7) | 251 (56.18) | |

| Dyslipidemia | 0.16 | |||

| No | 2994 (74.06) | 2689 (74.46) | 305 (70.84) | |

| Yes | 1068 (25.94) | 935 (25.54) | 133 (29.16) | |

| Diabetes mellitus | 0.945 | |||

| No | 3203 (78.88) | 2864 (78.87) | 339 (79.02) | |

| Yes | 859 (21.12) | 760 (21.13) | 99 (20.98) |

| Unadjusted Model | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| uOR (95% CI) | p Value | aOR (95% CI) | p Value | aOR (95% CI) | p Value | aOR (95% CI) | p Value | |

| Unmet needs | ||||||||

| No | 1.00 (ref.) | NA | 1.00 (ref.) | NA | 1.00 (ref.) | NA | 1.00 (ref.) | NA |

| Yes | 5.84 (4.35, 7.85) | <0.001 | 5.07 (3.7, 6.95) | <0.001 | 4.44 (3.24, 6.10) | <0.001 | 4.30 (3.12, 5.93) | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Seok, J.-W.; Kim, K.; Kim, J.U.; Yim, M.H. Association Between Unmet Healthcare Needs and Depression in Older Adults: Evidence from the Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Healthcare 2025, 13, 2635. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13202635

Seok J-W, Kim K, Kim JU, Yim MH. Association Between Unmet Healthcare Needs and Depression in Older Adults: Evidence from the Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Healthcare. 2025; 13(20):2635. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13202635

Chicago/Turabian StyleSeok, Ji-Woo, Kahye Kim, Jaeuk U. Kim, and Mi Hong Yim. 2025. "Association Between Unmet Healthcare Needs and Depression in Older Adults: Evidence from the Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey" Healthcare 13, no. 20: 2635. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13202635

APA StyleSeok, J.-W., Kim, K., Kim, J. U., & Yim, M. H. (2025). Association Between Unmet Healthcare Needs and Depression in Older Adults: Evidence from the Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Healthcare, 13(20), 2635. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13202635