Associations Between Makeup Use and Physical, Cognitive, and Psychological Functions in Community-Dwelling Older Women

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

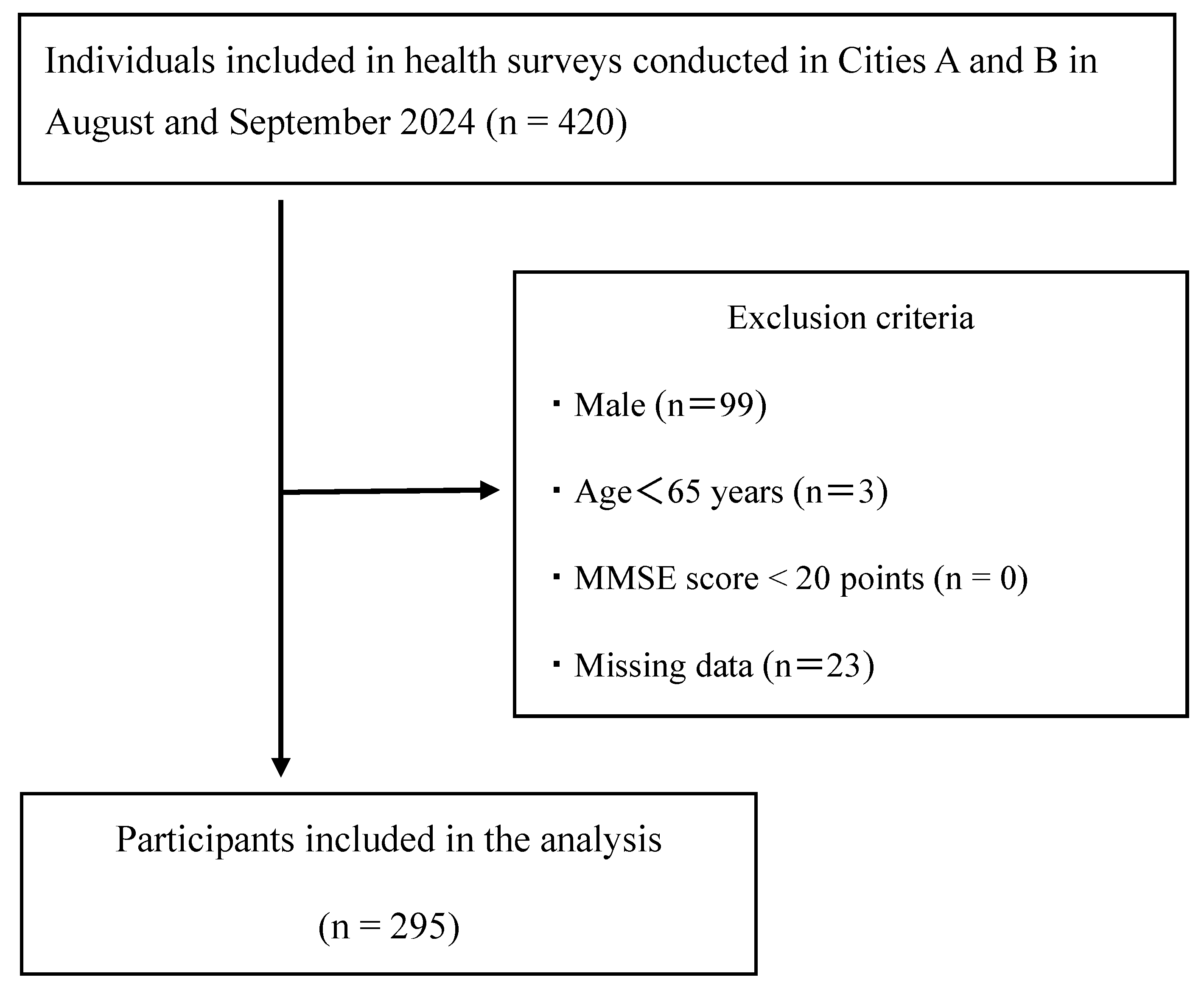

2.1. Participants

2.2. Measurements and Procedures

2.2.1. Current Makeup Usage Status

2.2.2. Physical Function

2.2.3. Cognitive Function

2.2.4. Psychological Function

2.3. Statistical Analysis

2.4. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| TUG | timed up-and-go test |

| MMSE | Mini-Mental State Examination |

| GDS-5 | Geriatric Depression Scale-5 |

| EQ-5D-5L | EuroQol 5 Dimensions 5 Levels |

References

- Japan Cabinet Office. Annual Report on the Aging Society [Summary] FY2024. Available online: https://www8.cao.go.jp/kourei/english/annualreport/2024/pdf/2024.pdf (accessed on 17 July 2025).

- Liang, L.Y. The impact of social participation on the quality of life among older adults in China: A chain mediation analysis of loneliness, depression, and anxiety. Front. Public Health 2024, 12, 1473657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Cao, X.; Wang, A.; Zhu, Y.; Lu, G.; Zhang, L.; Shen, L. A global perspective on risk factors for social isolation in community-dwelling older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2024, 116, 105211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbaniak, A.; Walsh, K.; Batista, L.G.; Kafkova, M.P.; Sheridan, C.; Serrat, R.; Rothe, F. Life-course transitions and exclusion from social relations in the lives of older men and women. J. Aging Stud. 2023, 67, 101188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, H.O.; Taylor, R.J.; Nguyen, A.W.; Chatters, L. Social isolation, depression, and psychological distress among older adults. J. Aging Health. 2018, 30, 229–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.R.; Jung, H.S. Effects of social interaction and depression on homeboundness in community-dwelling older adults living alone. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2008, 19, 3608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- US Food and Drug Administration. How U.S. Law Defines Cosmetic and Cosmetic Product. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/cosmetics/cosmetics-laws-regulations/cosmetics-us-law#US_Law (accessed on 17 July 2025).

- Yamaguchi, M.; Araki, D.; Kanamori, T.; Okiyama, Y.; Seto, H.; Uda, M.; Usami, M.; Yamamoto, Y.; Masunaga, T.; Sasa, H. Actual consumption amount of personal care products reflecting Japanese cosmetic habits. J. Toxicol. Sci. 2017, 42, 797–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Korichi, R.; Pelle-de-Queral, D.; Gazano, G.; Aubert, A. Why women use makeup: Implication of psychological traits in makeup functions. J. Cosmet. Sci. 2008, 59, 127–137. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Twigg, J.; Majima, S. Consumption and the constitution of age: Expenditure patterns on clothing, hair and cosmetics among post-war “baby boomers”. J. Aging Stud. 2014, 30, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatta, T.; Hatta, T. Cosmetic acts and frontal cortex function in upper middle-aged Japanese women. Int. J. Psychol. Behav. Sci. 2012, 1, 63–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vecoso, M.C.; Bagatin, E.; Fonseca, F.L.A.; Andreo-Filho, N.; Lopes, P.S.; Leite-Silva, V.R. Association between frequent use of makeup and presence of depressive symptoms-population-based observational study, including 2400 participants. Dermatol. Ther. 2023, 13, 1083–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, K.J. The perception of makeup for the elderly and the makeup behavior of new seniors. J. Consum. Behav. 2019, 19, 160–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, H.W.; Chen, H.C.; Lin, L.L. Association between out-of-home trips and older adults’ functional fitness. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 2014, 14, 596–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pachet, A.; Astner, K.; Brown, L. Clinical utility of the mini-mental status examination when assessing decision-making capacity. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry Neurol. 2010, 23, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, L.H.; Bundon, A. From ‘the thing to do’ to ‘defying the ravages of age’: Older women reflect on the use of lipstick. J. Women Aging 2009, 21, 198–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsushita, S.; Morikawa, K.; Mitsuzane, S.; Yamanami, H. Eye shape illusions induced by eyebrow positions. Perception 2015, 44, 529–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada, Y.; Watanabe, Y.; Ikenaga, M.; Yokoyama, K.; Yoshida, T.; Morimoto, T.; Kimura, M. Comparison of single- or multifrequency bioelectrical impedance analysis and spectroscopy for assessment of appendicular skeletal muscle in the elderly. J. Appl. Physiol. 2013, 115, 812–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwase, H.; Murata, S.; Nakano, H.; Shiraiwa, K.; Abiko, T.; Goda, A.; Nonaka, K.; Anami, K.; Hori, J. Relationship between age-related changes in skeletal muscle mass and physical function: A cross-sectional study of an elderly Japanese population. Cureus 2022, 14, e24260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wada, Y.; Shojima, K.; Tamaki, K.; Mori, T.; Kusunoki, H.; Onishi, M.; Tsuji, S.; Matsuzawa, R.; Nagai, K.; Sano, K.; et al. Association between timed up-and-go test and future changes in the frailty status in a longitudinal study of Japanese community-dwelling older adults. Clin. Interv. Aging 2023, 18, 1191–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimada, H.; Ishii, K.; Makizako, H.; Ishiwata, K.; Oda, K.; Suzukawa, M. Effects of exercise on brain activity during walking in older adults: A randomized controlled trial. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2017, 14, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folstein, M.F.; Folstein, S.E.; McHugh, P.R. “Mini-mental state.” A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J. Psychiatr. Res. 1975, 12, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinaldi, P.; Mecocci, P.; Benedetti, C.; Ercolani, S.; Bregnocchi, M.; Menculini, G.; Catani, M.; Senin, U.; Cherubini, A. Validation of the five-item geriatric depression scale in elderly subjects in three different settings. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2003, 51, 694–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wada, Y.; Murata, C.; Hirai, H.; Kondo, N.; Kondo, K.; Ueda, K.; Ichida, N. Predictive validity of GDS5 usingAGES project data. Kousei No Shihyou 2014, 61, 7–12. [Google Scholar]

- Goda, A.; Murata, S.; Nakano, H.; Nonaka, K.; Iwase, H.; Shiraiwa, K.; Abiko, T.; Anami, K.; Horie, J. The relationship between subjective cognitive decline and health literacy in healthy community-dwelling older adults. Healthcare 2020, 8, 567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herdman, M.; Gudex, C.; Lloyd, A.; Janssen, M.; Kind, P.; Parkin, D.; Bonsel, G.; Badia, X. Development and preliminary testing of the new five-level version of EQ-5D (EQ-5D-5L). Qual. Life Res. 2011, 20, 1727–1736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiroiwa, T.; Ikeda, S.; Noto, S.; Igarashi, A.; Fukuda, T.; Saito, S.; Shimozuma, K. Comparison of value set based on DCE and/or TTO data: Scoring for EQ-5D-5L health states in Japan. Value Health 2016, 19, 648–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oizumi, R.; Shibata, R. Association between lifestyle and skin moisturizing function in community-dwelling older adults. Dermatol. Reports 2024, 16, 9964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuge, K.; Kito, T. Make-up behavior in elderly women. Kurume Univ. Psychol. Res. 2015, 14, 17–24. [Google Scholar]

- Moscicka, P.; Chrost, N.; Terlikowski, R.; Przylipiak, M.; Wolosik, K.; Przylipiak, A. Hygienic and cosmetic care habits in Polish women during COVID-19 pandemic. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2020, 19, 1840–1845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fristedt, S.; Kammerlind, A.S.; Fransson, E.I.; Ernsth Bravell, M. Physical functioning associated with life-space mobility in later life among men and women. BMC Geriatr. 2022, 22, 364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Echizenya, Y.; Kazunori, A.; Haruka, T.; Ken, N.; Hoshi, F. Characteristics of balance ability related to life space of older adults in a day care center. Cogent Med. 2020, 7, 1714532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sternang, O.; Reynolds, C.A.; Finkel, D.; Ernsth-Bravell, M.; Pedersen, N.L.; Dahl Aslan, A.K. Factors associated with grip strength decline in older adults. Age Ageing 2015, 44, 269–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaei, A.; Bhat, S.G.; Cheng, C.H.; Pignolo, R.J.; Lu, L.; Kaufman, K.R. Age-related changes in gait, balance, and strength parameters: A cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0310764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meulemans, L.; Deboutte, J.; Seghers, J.; Delecluse, C.; Van Roie, E. Age-related differences across the adult lifespan: A comparison of six field assessments of physical function. Aging. Clin. Exp. Res. 2025, 37, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogawa, S.; Himuro, N.; Koyama, M.; Seko, T.; Mori, M.; Ohnishi, H. Walking speed is better than hand grip strength as an indicator of early decline in physical function with age in Japanese women over 65: A longitudinal analysis of the Tanno-Sobetsu study using linear mixed-effects models. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 15769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuevo, P.S.; Crrestani, S.; Ribas, J.L.C. The effect of make-up on the emotions and the perception of beauty. Res. Soc. Dev. 2021, 10, e3211019315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shekhawat, K. The psychological effects of makeup: Self perception, confidence and social Interaction. Int. J. Adv. Res. 2024, 12, 925–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Worrall, C.; Jongenelis, M.I.; McEvoy, P.M.; Jackson, B.; Newton, R.U.; Pettigrew, S. An exploratory study of the relative effects of various protective factors on depressive symptoms among older people. Front. Public Health 2020, 8, 579304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maier, A.; Riedel-Heller, S.G.; Pabst, A.; Luppa, M. Risk factors and protective factors of depression in older people 65+. A systematic review. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0251326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujita, W.; Wada, Y. Changes in health-related quality of life for elderly people after make-up therapy in a nursing care prevention class. Nurs. Prim. Care. 2020, 4, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Liu, Y.F.; Huang, G.D.; Wu, P.C. The relationship between physical exercise and subjective well-being in Chinese older people: The mediating role of the sense of meaning in life and self-esteem. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 1029587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keikavoosi-Arani, L.; Salehi, L. Cultural adaptation and psychometric adequacy of the Persian version of the physical activity scale for the elderly (P-PASE). BMC Res. Notes 2019, 12, 555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variables | Make-Up Group (n = 212) | Non-Makeup Group (n = 83) | t-Test p-Value | ANCOVA p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 74.1 ± 5.3 | 76.3 ± 5.1 | 0.001 | — |

| Grip strength (kg) | 22.9 ± 3.6 | 21.7 ± 4.2 | 0.011 | 0.096 |

| Sit-and-reach distance (cm) | 35.7 ± 7.9 | 35.4 ± 10.1 | 0.778 | 0.854 |

| One-leg standing time (s) | 40.0 ± 35.6 | 28.3 ± 28.5 | 0.008 | 0.148 |

| TUG (s) | 5.9 ± 0.9 | 6.2 ± 1.1 | 0.011 | 0.208 |

| Maximum walking speed (cm/sec) | 189.1 ± 30.3 | 180.3 ± 27.5 | 0.022 | 0.154 |

| MMSE (points) | 28.3 ± 1.9 | 27.9 ± 2.1 | 0.12 | 0.285 |

| GDS-5 (points) | 0.6 ± 1.0 | 0.9 ± 1.1 | 0.009 | 0.008 |

| EQ-5D-5L (points) | 0.893 ± 0.099 | 0.866 ± 0.114 | 0.049 | 0.038 |

| Variables | Lipstick | Eyebrow Products | Both | Neither | ANOVA | ANCOVA | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (a) | (b) | (c) | (d) | |||||||

| (n = 45) | (n = 40) | (n = 102) | (n = 108) | F-Value | p-Value | Post hoc | F-Value | p-Value | Post hoc | |

| Age (years) | 76.0 ± 5.6 | 72.7 ± 5.6 | 74.0 ± 4.9 | 75.6 ± 5.4 | 4.598 | 0.004 | a > b, b < d | — | — | — |

| Grip strength (kg) | 22.9 ± 3.4 | 23.3 ± 4.0 | 22.8 ± 3.8 | 22.0 ± 3.9 | 1.644 | 0.179 | — | 1.014 | 0.387 | — |

| Sit-and-reach distance (cm) | 35.0 ± 8.0 | 33.0 ± 8.7 | 37.0 ± 7.4 | 35.6 ± 9.4 | 2.305 | 0.077 | — | 2.339 | 0.074 | — |

| One-leg standing time (s) | 38.0 ± 36.5 | 36.6 ± 34.3 | 41.7 ± 35.4 | 31.5 ± 31.4 | 1.604 | 0.189 | — | 1.395 | 0.245 | — |

| TUG (s) | 6.0 ± 0.9 | 5.9 ± 1.0 | 5.7 ± 0.8 | 6.2 ± 1.1 | 4.166 | 0.007 | c < d | 3.085 | 0.028 | c < d |

| Maximum walking speed (cm/sec) | 187.4 ± 26.5 | 188.2 ± 35.6 | 191.3 ± 30.5 | 181.3 ± 27.4 | 2.053 | 0.107 | — | 1.366 | 0.253 | — |

| MMSE (points) | 28.3 ± 1.9 | 28.7 ± 1.9 | 28.3 ± 1.9 | 28.0 ± 2.0 | 1.276 | 0.283 | — | 0.808 | 0.490 | — |

| GDS-5 (points) | 0.8 ± 1.2 | 0.7 ± 1.0 | 0.4 ± 0.7 | 0.9 ± 1.1 | 5.094 | 0.002 | c < d | 5.153 | 0.002 | c < d |

| EQ-5D-5L (points) | 0.877 ± 0.119 | 0.891 ± 0.103 | 0.907 ± 0.089 | 0.866 ± 0.108 | 2.926 | 0.034 | c > d | 3.142 | 0.026 | c > d |

| (n = 295) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lipstick | Eyebrows | Both | ||||

| (n = 45) | (n = 40) | (n = 102) | ||||

| Variable | OR (95% CI) | p-Value | OR (95% CI) | p-Value | OR (95% CI) | p-Value |

| Age | 1.04 (0.970–1.127) | 0.248 | 0.91 (0.833–0.982) | 0.017 | 0.97 (0.912–1.032) | 0.334 |

| Grip strength | 1.07 (0.963–1.181) | 0.219 | 1.05 (0.944–1.171) | 0.358 | 1.00 (0.916–1.082) | 0.920 |

| TUG | 0.85 (0.552–1.303) | 0.452 | 1.14 (0.747–1.729) | 0.551 | 0.65 (0.448–0.952) | 0.027 |

| MMSE | 1.06 (0.889–1.272) | 0.533 | 1.17 (0.947–1.444) | 0.147 | 1.02 (0.883–1.185) | 0.759 |

| GDS-5 | 0.94 (0.662–1.328) | 0.717 | 0.88 (0.600–1.269) | 0.524 | 0.59 (0.415–0.843) | 0.004 |

| EQ-5D-5L | 1.43 (0.039–51.836) | 0.846 | 8.82 (0.158–491.944) | 0.289 | 8.16 (0.375–177.470) | 0.181 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Matori, S.; Murata, S.; Kikuchi, Y.; Nakano, H.; Katsurasako, T.; Iwamoto, K.; Mori, K.; Goda, A.; Kamijo, K. Associations Between Makeup Use and Physical, Cognitive, and Psychological Functions in Community-Dwelling Older Women. Healthcare 2025, 13, 2618. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13202618

Matori S, Murata S, Kikuchi Y, Nakano H, Katsurasako T, Iwamoto K, Mori K, Goda A, Kamijo K. Associations Between Makeup Use and Physical, Cognitive, and Psychological Functions in Community-Dwelling Older Women. Healthcare. 2025; 13(20):2618. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13202618

Chicago/Turabian StyleMatori, Shinya, Shin Murata, Yuki Kikuchi, Hideki Nakano, Takeshi Katsurasako, Kohei Iwamoto, Kohei Mori, Akio Goda, and Kenji Kamijo. 2025. "Associations Between Makeup Use and Physical, Cognitive, and Psychological Functions in Community-Dwelling Older Women" Healthcare 13, no. 20: 2618. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13202618

APA StyleMatori, S., Murata, S., Kikuchi, Y., Nakano, H., Katsurasako, T., Iwamoto, K., Mori, K., Goda, A., & Kamijo, K. (2025). Associations Between Makeup Use and Physical, Cognitive, and Psychological Functions in Community-Dwelling Older Women. Healthcare, 13(20), 2618. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13202618