Perinatal Identification, Referral, and Integrated Management for Improving Depression: Development, Feasibility and Pilot Randomised Controlled Trial of the PIRIMID System

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Universal Screening

1.2. Electronic Clinical Decision Support Systems

1.3. The PIRIMID System

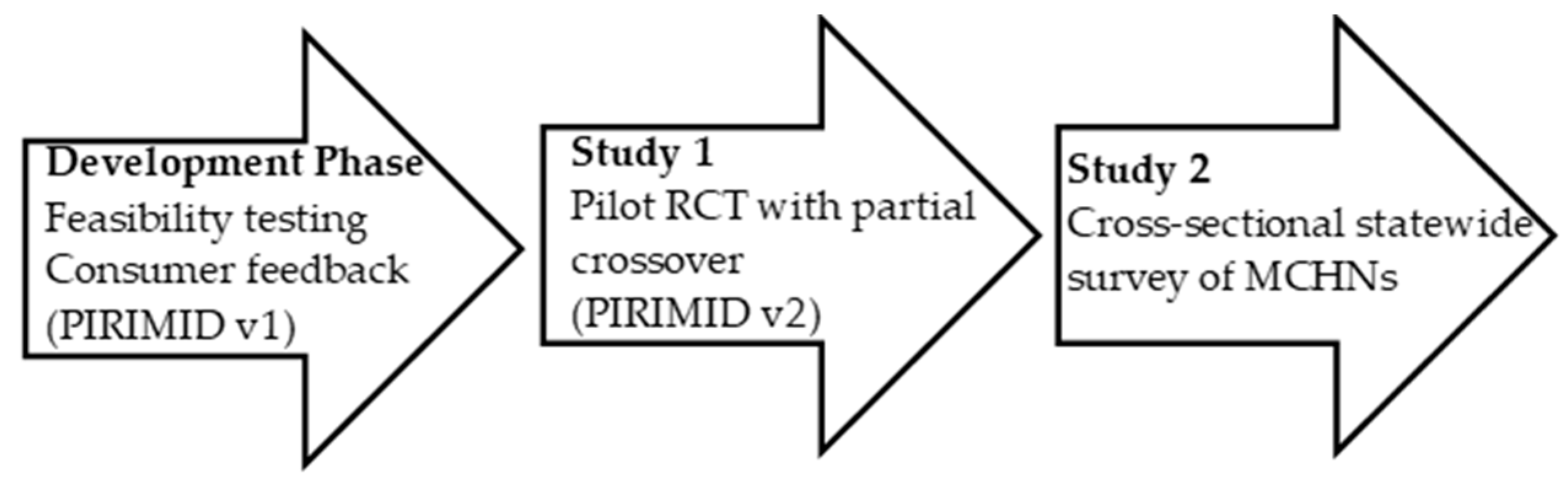

2. Methods

2.1. Development of the PIRIMID System and Feasibility

2.1.1. Conceptualisation

2.1.2. Description of the PIRIMID System

2.1.3. Feasibility and Iterations of the PIRIMID System

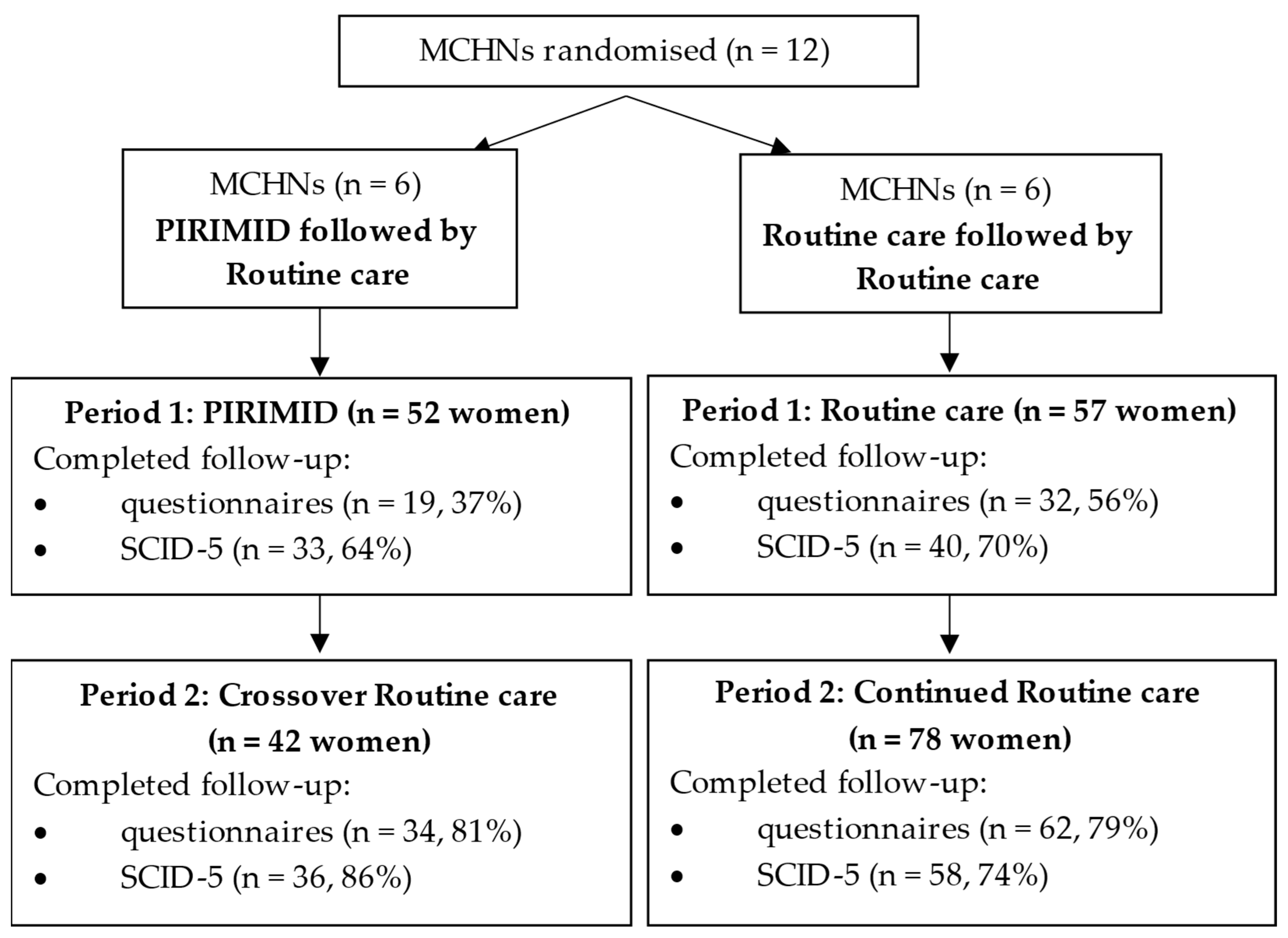

2.2. Study 1: PIRIMID Versus Routine Care: Randomized Controlled Trial with Partial Crossover

2.2.1. Trial Design

2.2.2. Participants

2.2.3. Eligibility Criteria

2.2.4. Interventions

2.2.5. Measures

2.2.6. Maternal Outcome Measures

2.2.7. MCHN Outcomes Measures

2.2.8. Sample Size

2.2.9. Randomisation

2.2.10. Blinding

2.2.11. Statistical Methods

2.3. Study 2: Statewide Survey of MCHNs

2.3.1. Study Design and Participants

2.3.2. Procedure

2.3.3. Survey

2.3.4. Statistical Methods

3. Results

3.1. Study 1: PIRIMID Versus Routine Care: Randomized Controlled Trial with Partial Crossover

3.1.1. Participant Flow

3.1.2. Baseline Characteristics

3.1.3. Maternal Outcomes

3.1.4. MCHN Outcomes

3.2. Study 2: Statewide Survey of MCHNs

3.2.1. Benefits to Using the PIRIMID System

- 1.

- Ensuring best practice

- 2.

- Efficiency

3.2.2. Barriers to Using the PIRIMID System

- 1.

- Time constraints

- 2.

- Technical barriers

3.2.3. What Makes It Possible/Easier to Use in Practice

- 1.

- Easy access such as integration with current systems

- 2.

- Sufficient time and training

3.2.4. How Screening Mothers for Depression and Anxiety Could Be Improved

- 1.

- Sufficient time

- 2.

- Timing and frequency

- 3.

- Referral pathways

4. Discussion

4.1. Rates of Referral and Treatment Uptake

4.2. Depression, Anxiety and Stress

4.3. Acceptability of the PIRIMID System

4.4. Screening Rates

4.5. Future Research

- (1)

- Version 2 of PIRIMID (used in the pilot RCT) has been updated and improved to version 3, as described in the methods, with a view to enhancing system usability.

- (2)

- Training to use PIRIMID has been completely revamped and a digital training package developed that can be completed at the user’s convenience.

- (3)

- Data collection and follow-up processes were revised to increase automation.

- (4)

- The emotional health assessment has been moved to the 8-week KAS visit. This allows MCHNs to introduce the study at the 4-week KAS visit.

- (5)

- Lack of time was an important factor repeatedly identified by MCHNs, so participating services have allocated an additional 15 min to 8-week KAS visits for study MCHNs.

- (6)

- An option to complete e-screening via a link sent to the woman’s mobile device prior to her KAS visit has been added.

- (7)

- Inclusion of a health economic evaluation to assess cost-effectiveness of the PIRIMID system.

4.6. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gavin, N.I.; Gaynes, B.N.; Lohr, K.N.; Meltzer-Brody, S.; Gartlehner, G.; Swinson, T. Perinatal Depression: A Systematic Review of Prevalence and Incidence. Obstet. Gynecol. 2005, 106, 1071–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Wang, S.; Wang, G. Prevalence and risk factors of postpartum depression in women: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Clin. Nurs. 2022, 31, 2665–2677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shorey, S.; Chee, C.Y.I.; Ng, E.D.; Chan, Y.H.; San Tam, W.W.; Chong, Y.S. Prevalence and incidence of postpartum depression among healthy mothers: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2018, 104, 235–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dennis, C.L.; Falah-Hassani, K.; Shiri, R. Prevalence of antenatal and postnatal anxiety: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Br. J. Psychiatry 2017, 210, 315–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Li, Q.; Cheng, K.K.; Caine, E.D.; Tong, Y.; Wu, X.; Gong, W.; Carona, C. Prevalence of Postpartum Depression Based on Diagnostic Interviews: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Depress. Anxiety 2023, 2023, 8403222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Abri, K.; Edge, D.; Armitage, C.J. Prevalence and correlates of perinatal depression. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2023, 58, 1581–1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letourneau, N.L.; Dennis, C.L.; Benzies, K.; Duffett-Leger, L.; Stewart, M.; Tryphonopoulos, P.D.; Este, D.; Watson, W. Postpartum depression is a family affair: Addressing the impact on mothers, fathers, and children. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 2012, 33, 445–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, A.; Pearson, R.M.; Goodman, S.H.; Rapa, E.; Rahman, A.; McCallum, M.; Howard, L.M.; Pariante, C.M. Effects of perinatal mental disorders on the fetus and child. Lancet 2014, 384, 1800–1819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bauer, A.; Pawlby, S.; Plant, D.T.; King, D.; Pariante, C.M.; Knapp, M. Perinatal depression and child development: Exploring the economic consequences from a South London cohort. Psychol. Med. 2014, 45, 51–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- PwC Consulting Australia. The Price of Perinatal Depression and Anxiety in Australia. Available online: https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/62b502ec3eba99ddd594f70a/637c637165e7d3c54a6eccd5_Cost-of-PNDA-in-Australia_-Final-Report.pdf (accessed on 16 September 2025).

- Reilly, N.; Kingston, D.; Loxton, D.; Talcevska, K.; Austin, M.P. A narrative review of studies addressing the clinical effectiveness of perinatal depression screening programs. Women Birth 2020, 33, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, J.; Cong, S.; Sun, X.; Xie, H.; Ni, S.; Zhang, A. Uptake rate of interventions among women who screened positive for perinatal depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2024, 361, 739–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, E.Q.; Sowa, N.A.; Meltzer-Brody, S.E.; Gaynes, B.N. The perinatal depression treatment cascade: Baby steps toward improving outcomes. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2016, 77, 1189–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gavin, N.; Meltzer-Brody, S.; Glover, V.; Gaynes, B. Is population-based identification of perinatal depression and anxiety desirable? A public health perspective on the perinatal depression care continuum. In Identifying Perinatal Depression and Anxiety: Evidence-Based Practice in Screening, Psychosocial Assessment and Management; Milgrom, J., Gemmill, A.W., Eds.; Wiley: Chichester, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Arefadib, N.; Cooklin, A.; Nicholson, J.; Shafiei, T. Postnatal depression and anxiety screening and management by maternal and child health nurses in community settings: A scoping review. Midwifery 2021, 100, 103039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medlock, S.; Wyatt, J.C.; Patel, V.L.; Shortliffe, E.H.; Abu-Hanna, A. Modeling information flows in clinical decision support: Key insights for enhancing system effectiveness. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2016, 23, 1001–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torti, J.; Klein, C.; Foster, M.; Shields, L.E. A systemwide postpartum inpatient maternal mental health education and screening program. Nurs. Womens Health 2023, 27, 179–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yawn, B.P.; Olson, A.L.; Bertram, S.; Pace, W.; Wollan, P.; Dietrich, A.J. Postpartum depression: Screening, diagnosis, and management programs 2000 through 2010. Depress. Res. Treat. 2012, 2012, 363964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, E.S.; Grobman, W.A.; Ciolino, J.D.; Zumpf, K.; Sakowicz, A.; Gollan, J.; Wisner, K.L. Increased depression screening and treatment recommendations after implementation of a perinatal collaborative care program. Psychiatr. Serv. 2021, 72, 1268–1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutton, R.T.; Pincock, D.; Baumgart, D.C.; Sadowski, D.C.; Fedorak, R.N.; Kroeker, K.I. An overview of clinical decision support systems: Benefits, risks, and strategies for success. npj Digit. Med. 2020, 3, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfoh, E.R.; Janmey, I.; Anand, A.; Martinez, K.A.; Katzan, I.; Rothberg, M.B. The impact of systematic depression screening in primary care on depression identification and treatment in a large health care system: A cohort study. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2020, 35, 3141–3147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fletcher, S.; Chondros, P.; Densley, K.; Murray, E.; Dowrick, C.; Coe, A.; Hegarty, K.; Davidson, S.; Wachtler, C.; Mihalopoulos, C.; et al. Matching depression management to severity prognosis in primary care: Results of the Target-D randomised controlled trial. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 2021, 71, e85–e94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chondros, P.; Davidson, S.; Wolfe, R.; Gilchrist, G.; Dowrick, C.; Griffiths, F.; Hegarty, K.; Herrman, H.; Gunn, J. Development of a prognostic model for predicting depression severity in adult primary patients with depressive symptoms using the Diamond Longitudinal Study. J. Affect. Disord. 2018, 227, 854–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunn, J.; Wachtler, C.; Fletcher, S.; Davidson, S.; Mihalopoulos, C.; Palmer, V.; Hegarty, K.; Coe, A.; Murray, E.; Dowrick, C.; et al. Target-D: A stratified individually randomized controlled trial of the Diamond Clinical Prediction Tool to triage and target treatment for depressive symptoms in general practice: Study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials 2017, 18, 342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, T.; Young, K.; Darragh, M.; Corter, A.; Soosay, I.; Goodyear-Smith, F. Perinatal e-screening and clinical decision support: The maternity case-finding help assessment tool (MatCHAT). J. Prim. Health Care 2020, 12, 265–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Highet, N.J.; The Expert Working Group and Expert Subcommittees. Mental Health Care in the Perinatal Period: Australian Clinical Practice Guideline. Melbourne. Available online: https://www.cope.org.au/uploads/images/Health-professionals/COPE_2023_Perinatal_Mental_Health_Practice_Guideline.pdf (accessed on 16 September 2025).

- Cox, J.L.; Holden, J.M.; Sagovsky, R. Detection of postnatal depression: Development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. Br. J. Psychiatry 1987, 150, 782–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matthey, S.; Fisher, J.; Rowe, H. Using the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale to screen for anxiety disorders: Conceptual and methodological considerations. J. Affect. Disord. 2013, 146, 224–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whooley, M.A.; Avins, A.L.; Miranda, J.; Browner, W.S. Case-finding instruments for depression: Two questions are as good as many. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 1997, 12, 439–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Antenatal and Postnatal Mental Health: Clinical Management and Service Guidance. Available online: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg192 (accessed on 16 September 2025).

- Lovibond, P.F.; Lovibond, S.H. The structure of negative emotional states: Comparison of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) with the Beck Depression and Anxiety Inventories. Behav. Res. Ther. 1995, 33, 335–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- First, M.B.; Williams, J.B.; Karg, R.S.; Spitzer, R.L. User’s Guide for the SCID-5-CV Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5® Disorders: Clinical Version; American Psychiatric Association Publishing: Washington, DC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Brooke, J. SUS: A quick and dirty usability scale. In Usability Evaluation in Industry; Jordan, P.W., Thomas, B., McClelland, I.L., Weerdmeester, B.A., Eds.; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Holt, C.; Milgrom, J.; Gemmill, A.W. Improving help-seeking for postnatal depression and anxiety: A cluster randomised controlled trial of motivational interviewing. Arch. Women’s Ment. Health 2017, 20, 791–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Quantitative methods in psychology: A power primer. Psychol. Bull. 1992, 112, 1155–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Mascio, V.; Kent, A.; Fiander, M.; Lawrence, J. Recovery from postnatal depression: A consumer’s perspective. Arch. Women’s Ment. Health 2008, 11, 253–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Data Collected from Women | Data Collected from MCHNs | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4-Week KAS Visit (Baseline) | 3-Months Post-Birth (Follow-Up) | 4-Week Log | Study-End Feedback | |

| Maternal outcomes | ||||

| Referral rates | X | |||

| Treatment uptake | X | X | ||

| Depression, anxiety and stress symptoms | X | X | ||

| Depressive disorder | X | |||

| Acceptability to women | X | |||

| Participant demographics | X | |||

| MCHN outcomes | ||||

| Screening rates | X | |||

| Staff time | X | X (PIRIMID MCHNs only) | ||

| Acceptability to MCHNs | X (PIRIMID MCHNs only) | |||

| PIRIMID Followed by Routine Care | Routine care Followed by Routine Care | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Period 1: PIRIMID System (n = 52) | Period 2: Routine Care (n = 42) | Period 1: Routine Care (n = 57) | Period 2: Routine Care (n = 78) | |

| Maternal characteristics | ||||

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 31.8 (4.6) | 31.3 (3.9) | 31.8 (4.1) | 32.4 (4.1) |

| Marital status, n/N (%) | ||||

| Married/living with partner | 51/52 (98%) | 38/40 (91%) | 57/57 (100%) | 73/75 (94%) |

| No partner | 1/52 (2%) | 2/40 (5%) | 0 | 2/75 (3%) |

| Born in Australia, n/N (%) | 29/52 (56%) | 31/42 (74%) | 44/57 (77%) | 63/77 (82%) |

| Highest education, n/N (%) | ||||

| Certificate level or less | 15/52 (29%) | 13/42 (31%) | 11/57 (19%) | 19/78 (24%) |

| Advanced Diploma/ Diploma | 10/52 (19%) | 7/42 (17%) | 12/57 (21%) | 12/78 (15%) |

| Undergraduate degree | 9/52 (17%) | 14/42 (33%) | 11/57 (19%) | 22/78 (28%) |

| Postgraduate degree | 15/52 (29%) | 7/42 (17%) | 20/57 (35%) | 24/78 (31%) |

| Other | 3/52 (6%) | 1/42 (2%) | 3/57 (5%) | 1/78 (1%) |

| Income, n/N (%) | ||||

| Up to AUD80,000 | 17/51 (33%) | 6/42 (14%) | 16/57 (28%) | 14/78 (18%) |

| Greater than AUD80,001 | 31/51 (61%) | 28/42 (67%) | 30/57 (53%) | 52/78 (67%) |

| Do not wish to divulge | 3/51 (6%) | 8/42 (19%) | 11/57 (19%) | 12/78 (15%) |

| Currently receiving counselling or psychological therapy, n/N (%) | ||||

| No | 50/52 (96%) | 38/42 (91%) | 51/57 (90%) | 73/78 (94%) |

| Yes | 2/52 (4%) | 4/42 (10%) | 6/57 (11%) | 5/78 (6%) |

| Once | 0 | 0 | 1/6 (17%) | 0 |

| Occasionally | 2/2 (100%) | 2/4 (50%) | 2/6 (33%) | 2/5 (40%) |

| Regularly | 0 | 2/4 (50%) | 3/6 (50%) | 3/5 (60%) |

| Currently taking antidepressants or medication for anxiety, n/N (%) | 2/52 (4%) | 3/42 (7%) | 5/57 (9%) | 2/78 (3%) |

| EPDS score, median (IQR) | 6 (3–10) | 6 (3–9) | 4 (3–8) | 6 (3–9) |

| EPDS score, n/N (%) | ||||

| No/minimal depression (0–9) | 38/52 (73%) | 32/42 (76%) | 49/55 (89%) | 63/77 (82%) |

| Mild depression (10–12) | 9/52 (17%) | 6/42 (14%) | 2/55 (4%) | 8/77 (10%) |

| Moderate to severe depression (13+) | 5/52 (10%) | 4/42 (10%) | 4/55 (7%) | 6/77 (8%) |

| Number of children, n/N (%) | ||||

| One | 23/52 (44%) | 25/42 (60%) | 30/56 (53%) | 45/78 (58%) |

| Two | 22/52 (42%) | 14/42 (33%) | 21/56 (38%) | 23/78 (30%) |

| Three or more | 7/52 (14%) | 3/42 (7%) | 5/56 (9%) | 10/78 (13%) |

| Cluster sizes, median (range) | 7 (5–21) | 5 (0–17) | 9 (0–18) | 12 (0–28) |

| PIRIMID Followed by Routine Care | Routine Care Followed by Routine Care | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Period 1: PIRIMID System (n = 52) | Period 2: Routine Care (n = 42) | Period 1: Routine Care (n = 57) | Period 2: Routine Care (n = 78) | |

| Referred by MCHN, n/N (%) [95% CI] | 4/22 (18%) [5–40%] | 6/41 (15%) [6–29%] | 3/29 (10%) [2–27%] | 7/52 (14%) [6–26%] |

| Treatment uptake, n/N (%) | ||||

| Between birth and 4- week KAS visit | 15/44 (34%) | 15/42 (36%) | 18/53 (34%) | 26/72 (36%) |

| Between 4-week KAS visit and 3-months post-birth a | 5/19 (26%) | 8/34 (24%) | 10/32 (31%) | 16/62 (26%) |

| Depression, median (IQR) | ||||

| At 4-week KAS visit | 1 (0–4) | 2 (0–6) | 1 (0–4) | 2 (0–6) |

| At 3-months post-birth | 2 (0–6) | 1 (0–8) | 2 (0–8) | 2 (0–6) |

| Moderate to severe depression, n/N (%) | ||||

| At 4-week KAS visit | 4/52 (8%) | 2/40 (5%) | 5/56 (9%) | 5/72 (7%) |

| At 3-months post-birth | 1/19 (5%) | 3/34 (9%) | 6/32 (19%) | 4/61 (7%) |

| Anxiety, median (IQR) | ||||

| At 4-week KAS visit | 2 (0–6) | 2 (0–6) | 2 (0–6) | 2 (0–4) |

| At 3-months post-birth | 2 (0–8) | 0 (0–4) | 2 (0–4) | 2 (0–4) |

| Moderate to severe anxiety, n/N (%) | ||||

| At 4-week KAS visit | 6/52 (12%) | 5/40 (13%) | 8/55 (15%) | 7/72 (10%) |

| At 3-months post-birth | 0 | 3/33 (9%) | 3/32 (9%) | 5/61 (8%) |

| Stress, median (IQR) | ||||

| At 4-week KAS visit | 7 (2–12) | 8 (4–14) | 6 (2–14) | 10 (4–14) |

| At 3-months post-birth | 6 (2–10) | 6 (0–14) | 8 (6–15) | 10 (4–14) |

| Moderate to severe stress, n/N (%) | ||||

| At 4-week KAS visit | 4/52 (8%) | 2/39 (5%) | 6/56 (11%) | 6/72 (8%) |

| At 3-months post-birth | 2/19 (11%) | 4/33 (12%) | 5/27 (16%) | 7/58 (12%) |

| Depressive disorder diagnosis at 3-months post-birth, n/N (%) | 2/33 (6%) | 3/36 (8%) | 6/40 (15%) | 3/58 (5%) |

| Emotional health assessment, median (IQR) | ||||

| Helpful | 9 (8–10) n = 51 | 9 (6–10) n = 42 | 10 (8–10) n = 57 | 8 (6–10) n = 73 |

| Comfortable | 9 (8–10) n = 52 | 9 (8–10) n = 42 | 10 (9–10) n = 57 | 9 (7–10) n = 73 |

| PIRIMID Followed by Routine Care | Routine Care Followed by Routine Care | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Period 1: PIRIMID System (n = 52) | Period 2: Routine Care (n = 42) | Period 1: Routine Care (n = 57) | Period 2: Routine Care (n = 78) | |

| Screened | ||||

| EPDS, n/N (%) | 52/52 (100%) | 42/42 (100%) | 57/57 (100%) | 77/78 (99%) |

| Whooley questions, n/N (%) | 51/52 (98%) | 13/40 (33%) | 6/28 (21%) | 13/52 (25%) |

| Psychosocial risk factors, n/N (%) | 52/52 (100%) | 18/40 (45%) | 25/27 (93%) | 43/52 (83%) |

| Duration of 4-week KAS visit, median (range) | 45 (45–60) n = 21 | 45 (30–60) n = 41 | 45 (40–60) n = 29 | 45 (30–60) n = 52 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Holt, C.; Maher, S.; Gemmill, A.W.; Booker, L.A.; Braat, S.; Koye, D.N.; Pani, B.; Buist, A.; Milgrom, J. Perinatal Identification, Referral, and Integrated Management for Improving Depression: Development, Feasibility and Pilot Randomised Controlled Trial of the PIRIMID System. Healthcare 2025, 13, 2578. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13202578

Holt C, Maher S, Gemmill AW, Booker LA, Braat S, Koye DN, Pani B, Buist A, Milgrom J. Perinatal Identification, Referral, and Integrated Management for Improving Depression: Development, Feasibility and Pilot Randomised Controlled Trial of the PIRIMID System. Healthcare. 2025; 13(20):2578. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13202578

Chicago/Turabian StyleHolt, Charlene, Sarah Maher, Alan W. Gemmill, Lauren A. Booker, Sabine Braat, Digsu N. Koye, Bianca Pani, Anne Buist, and Jeannette Milgrom. 2025. "Perinatal Identification, Referral, and Integrated Management for Improving Depression: Development, Feasibility and Pilot Randomised Controlled Trial of the PIRIMID System" Healthcare 13, no. 20: 2578. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13202578

APA StyleHolt, C., Maher, S., Gemmill, A. W., Booker, L. A., Braat, S., Koye, D. N., Pani, B., Buist, A., & Milgrom, J. (2025). Perinatal Identification, Referral, and Integrated Management for Improving Depression: Development, Feasibility and Pilot Randomised Controlled Trial of the PIRIMID System. Healthcare, 13(20), 2578. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13202578