The Role of Servant Leadership in Work Engagement Among Healthcare Professionals

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sampling Methods and Procedure

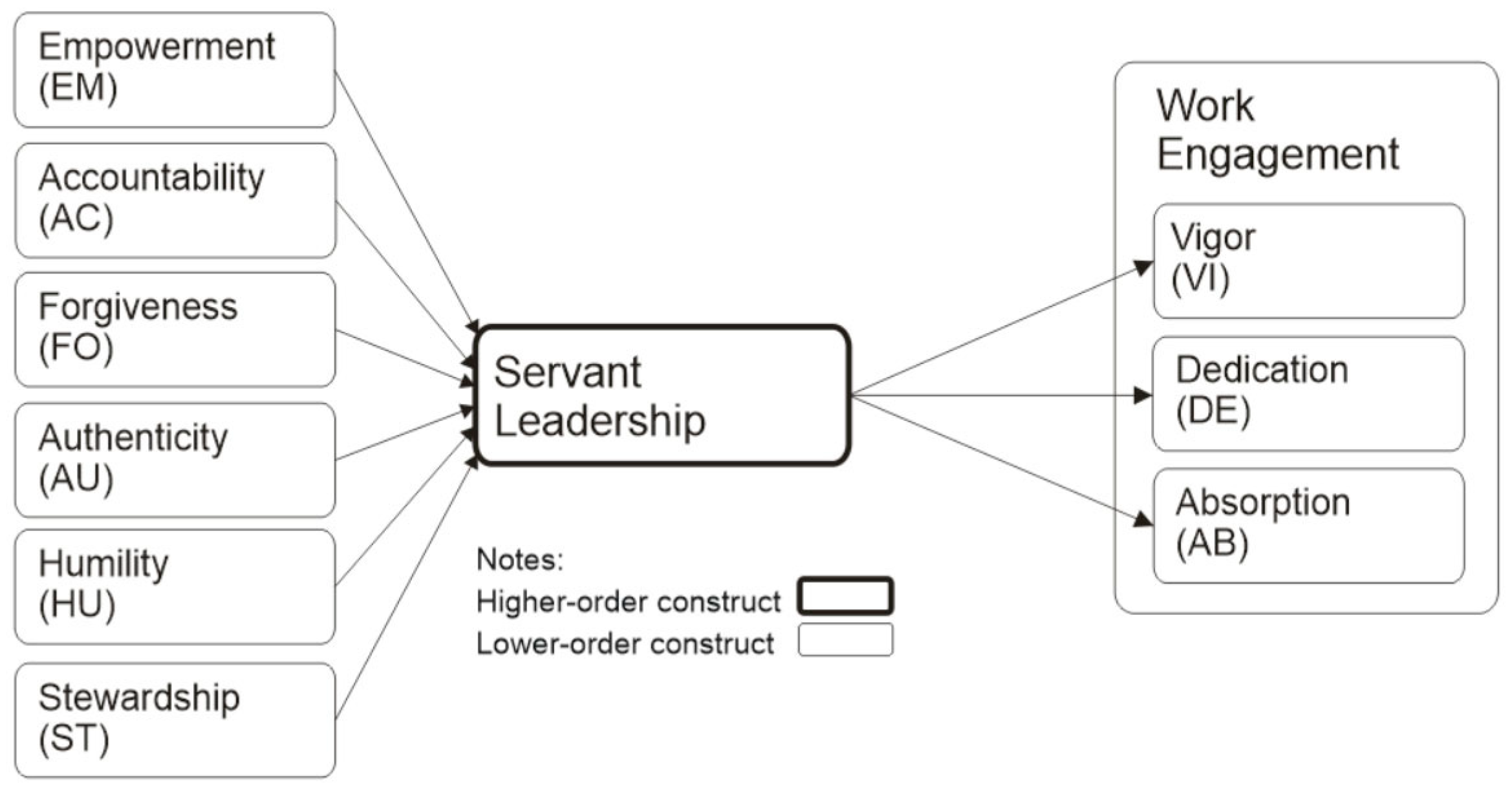

2.2. Survey Instrument and Measurement

3. Data Analysis

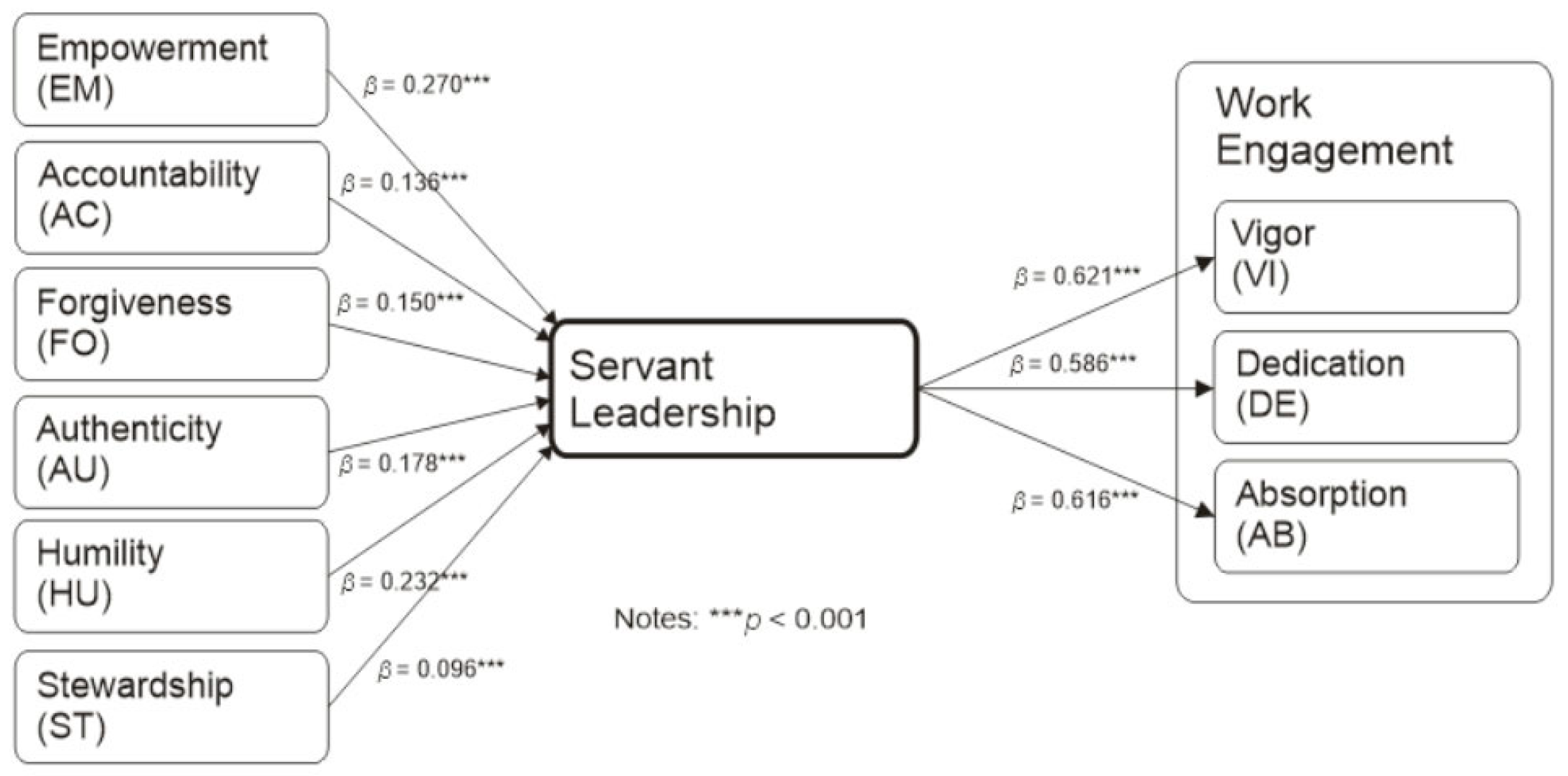

4. Results

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Galanis, P.; Katsiroumpa, A.; Vraka, I.; Siskou, O.; Konstantakopoulou, O.; Moisoglou, I.; Gallos, P.; Kaitelidou, D. The Quiet Quitting Scale: Development and Initial Validation. AIMS Public Health 2023, 10, 828–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moisoglou, I.; Katsiroumpa, A.; Katsapi, A.; Konstantakopoulou, O.; Galanis, P. Poor Nurses’ Work Environment Increases Quiet Quitting and Reduces Work Engagement: A Cross-Sectional Study in Greece. Nurs. Rep. 2025, 15, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galanis, P.; Moisoglou, I.; Katsiroumpa, A.; Vraka, I.; Siskou, O.; Konstantakopoulou, O.; Kaitelidou, D. Moral Resilience Reduces Levels of Quiet Quitting, Job Burnout, and Turnover Intention Among Nurses: Evidence in the Post COVID-19 Era. Nurs. Rep. 2024, 14, 254–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galanis, P.; Moisoglou, I.; Katsiroumpa, A.; Malliarou, M.; Vraka, I.; Gallos, P.; Kalogeropoulou, M.; Papathanasiou, I.V. Impact of Workplace Bullying on Quiet Quitting in Nurses: The Mediating Effect of Coping Strategies. Healthcare 2024, 12, 797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galanis, P.; Moisoglou, I.; Malliarou, M.; Papathanasiou, I.V.; Katsiroumpa, A.; Vraka, I.; Siskou, O.; Konstantakopoulou, O.; Kaitelidou, D. Quiet Quitting Among Nurses Increases Their Turnover Intention: Evidence from Greece in the Post-COVID-19 Era. Healthcare 2023, 12, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, D.; Hylton, R. Servant Leadership: Is This the Type of Leadership for Job Satisfaction Among Healthcare Employees? Indian J. Posit. Psychol. 2020, 11, 210–212. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, J.; Samad, S.; Comite, U.; Ahmad, N.; Han, H.; Ariza-Montes, A.; Vega-Munoz, A. Environmentally Specific Servant Leadership and Employees’ Energy-Specific Pro-Environmental Behavior: Evidence from Healthcare Sector of a Developing Economy. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 7641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alahbabi, A.M.F.M.; Robani, A.; Al-shami, S.A. A Framework of Servant Leadership Impact on Job Performance: The Mediation Role of Employee Happiness in UAE Healthcare Sector. Acad. Strateg. Manag. J. 2021, 20, 69–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.M.; Mubarik, M.S.; Ahmed, S.S.; Islam, T.; Khan, E.; Rehman, A.; Sohail, F. My Meaning is My Engagement: Exploring the Mediating Role of Meaning Between Servant Leadership and Work Engagement. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2021, 42, 926–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermanto, Y.B.; Srimulyani, V.A. The Relationship Between Servant Leadership and Work Engagement: An Organizational Justice as a Mediator. Acad. J. Interdiscip. Stud. 2022, 11, 403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Badi, F.M.; Cherian, J.; Farouk, S.; Al Nahyan, M. Work Engagement and Job Performance Among Nurses in the Public Healthcare Sector in the United Arab Emirates. J. Asia Bus. Stud. 2023, 17, 1019–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szilvassy, P.; Sirok, K. Importance of Work Engagement in Primary Healthcare. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2022, 22, 1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milojevic, S.; Aleksic, V.S.; Slavkovic, M. “Direct Me or Leave Me”: The Effect of Leadership Style on Stress and Self-Efficacy of Healthcare Professionals. Behav. Sci. 2024, 15, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grobler, A.; Flotman, A.-P. The Validation of the Servant Leadership Scale. SA J. Ind. Psychol. 2020, 46, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawar, A.; Sudan, K.; Satini, S.; Sunarsi, D. Organizational Servant Leadership: A Systematic Literature Review for Implications in Business. Int. J. Educ. Adm. Manag. Leadersh. 2020, 1, 63–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demeke, G.W.; van Engen, M.L.; Markos, S. Servant Leadership in the Healthcare Literature: A Systematic Review. J. Healthc. Leadersh. 2024, 16, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omanwar, S.P.; Agrawal, R.K. Servant Leadership, Organizational Identification and Turnover Intention: An Empirical Study in Hospitals. Int. J. Organ. Anal. 2021, 30, 239–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coetzer, M.; Bussin, M.; Geldenhuys, M. The Functions of a Servant Leader. Adm. Sci. 2017, 7, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bavik, A. A Systematic Review of the Servant Leadership Literature in Management and Hospitality. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 32, 347–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, R.F.; Stone, A.G. A Review of Servant Leadership Attributes: Developing a Practical Model. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2002, 23, 145–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Best, C. Is There a Place for Servant Leadership in Nursing? Pract. Nurs. 2020, 31, 128–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.M.; Mubarik, M.S.; Ahmed, S.S.; Islam, T.; Khan, E. The Contagious Servant Leadership: Exploring the Role of Servant Leadership in Leading Employees to Servant Colleagueship. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2022, 43, 847–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Dierendonck, D.; Nuijten, I. The Servant Leadership Survey: Development and Validation of a Multidimensional Measure. J. Bus. Psychol. 2011, 26, 249–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Dorssen-Boog, P.; de Jong, J.; Veld, M.; Van Vuuren, T. Self-Leadership Among Healthcare Workers: A Mediator for the Effects of Job Autonomy on Work Engagement and Health. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Salgado, J.; Domínguez-Salas, S.; Romero-Martín, M.; Romero, A.; Coronado-Vázquez, V.; Ruiz-Frutos, C. Work Engagement and Psychological Distress of Health Professionals During the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Nurs. Manag. 2021, 29, 1016–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, J.; Oh, J.; Park, J.; Kim, W. The Relationship Between Work Engagement and Work–Life Balance in Organizations: A Review of the Empirical Research. Hum. Resour. Dev. Rev. 2020, 19, 240–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydin, I. Effects of Work-Related Stressors and Work Engagement on Work Stress: Healthcare Managers’ Perspective. Cent. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2022, 11, 47–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bošković, A. Employee Autonomy and Engagement in the Digital Age: The Moderating Role of Remote Working. Ekon. Horiz. 2021, 23, 231–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storey, J.; Welbourne, T.; Wright, P.; Ulrich, D. Employee Engagement. In The Routledge Companion to Strategic Human Resource Management; Storey, J., Wright, P., Ulrich, D., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2008; pp. 299–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghazawy, E.R.; Mahfouz, E.M.; Mohammed, E.S.; Refaei, S.A. Nurses’ Work Engagement and Its Impact on the Job Outcomes. Int. J. Healthc. Manag. 2019, 14, 320–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milojević, S.; Slavković, M.; Knežević, S.; Zdravković, N.; Stojić, V.; Adamović, M.; Mirčetić, V. Concern or Opportunity: Implementation of the TBL Criterion in the Healthcare System. Systems 2024, 12, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stavrou, G.; Siskou, O.C.; Talias, M.A.; Galanis, P. Assessing Job Satisfaction and Stress Among Pharmacists in Cyprus. Pharmacy 2022, 10, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perić, G.; Slavković, M.; Gašić, M.; Đurović, B.; Dramićanin, S. Unboxing the Complex Between Job Satisfaction and Intangible Service Quality: A Perspective of Sustainability in the Hotel Industry. Sustainability 2023, 15, 14019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wee, K.Z.; Lai, A.Y. Work Engagement and Patient Quality of Care: A Meta-Analysis and Systematic Review. Med. Care Res. Rev. 2022, 79, 345–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nesic, D.; Slavkovic, M.; Zdravkovic, N.; Jerkan, N. Predictors of Perceived Healthcare Professionals’ Well-Being in Work Design: A Cross-Sectional Study with Multigroup PLS Structural Equation Modeling. Healthcare 2024, 12, 1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eva, N.; Robin, M.; Sendjaya, S.; van Dierendonck, D.; Liden, R.C. Servant Leadership: A systematic review and call for future research. Leadersh. Q. 2019, 30, 111–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palabiyik, N.; Yikilmaz, İ.; SÜRÜCÜ, L. Ways to Promote Employee Work Engagement in Healthcare Organizations: Servant Leadership and Organizational Justice. İktis. İdari Siyasal Araşt. Derg. 2023, 8, 153–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, M.; Wang, M.; Cheng, J. The Effect of Servant Leadership on Work Engagement: The Role of Employee Resilience and Organizational Support. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G.; Gul, R.; Tufail, M. Does Servant Leadership Stimulate Work Engagement? The Moderating Role of Trust in the Leader. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 925732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozturk, A.; Karatepe, O.M.; Okumus, F. The Effect of Servant Leadership on Hotel Employees’ Behavioral Consequences: Work Engagement Versus Job Satisfaction. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 97, 102994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaya, B.; Karatepe, O.M. Does Servant Leadership Better Explain Work Engagement, Career Satisfaction and Adaptive Performance Than Authentic Leadership? Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 32, 2075–2095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moisoglou, I.; Katsiroumpa, A.; Prasini, I.; Gallos, P.; Kalogeropoulou, M.; Galanis, P. Innovation Support Reduces Quiet Quitting and Improves Innovative Behavior and Innovation Outputs Among Nurses in Greece. Nurs. Rep. 2024, 14, 2618–2628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trastek, V.F.; Hamilton, N.W.; Niles, E.E. Leadership models in health care—A case for servant leadership. In Mayo Clinic Proceedings; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2014; Volume 89, pp. 374–381. [Google Scholar]

- Aij, K.H.; Rapsaniotis, S. Leadership requirements for Lean versus servant leadership in health care: A systematic review of the literature. J. Healthc. Leadersh. 2017, 9, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alharbi, M.F.; Kundi, G.M. Servant leadership and leadership effectiveness in healthcare institutions. Probl. Perspect. Manag. 2023, 21, 361–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cropanzano, R.; Mitchell, M.S. Social Exchange Theory: An Interdisciplinary Review. J. Manag. 2005, 31, 874–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Dierendonck, D. Servant Leadership: A Review and Synthesis. J. Manag. 2010, 37, 1228–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrington, S.M.; Lillah, R. Servant leadership and job satisfaction within private healthcare practices. Leadersh. Health Serv. 2019, 32, 148–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harness, K. Servant Leadership in Healthcare Settings: An Examination of Its Effects on Employee Engagement, Satisfaction, and Retention. Ph.D. Dissertation, The Chicago School of Professional Psychology, Chicago, IL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Kock, N.; Hadaya, P. Minimum sample size estimation in PLS-SEM: The inverse square root and gamma-exponential methods. Inf. Syst. J. 2018, 28, 227–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Institute of Public Health of Serbia. Health Statistical Yearbook of the Republic of Serbia 2022; Institute of Public Health of Serbia: Belgrade, Serbia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Westbrook, K.W.; Nicol, D.; Nicol, J.K.; Orr, D.T. Effects of servant leadership style on hindrance stressors, burnout, job satisfaction, turnover intentions, and individual performance in a nursing unit. J. Health Manag. 2022, 24, 670–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Bakker, A.B. Utrecht Work Engagement Scale: Preliminary Manual; Utrecht University: Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Petrović, I.B.; Vukelić, M.; Čizmić, S. Work Engagement in Serbia: Psychometric Properties of the Serbian Version of the Utrecht Work Engagement Scale (UWES). Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 1799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Sarstedt, M.; Hopkins, L.; Kuppelwieser, V.G. Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM): An emerging tool in business research. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2014, 26, 106–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M.; Mitchell, R.; Gudergan, S.P. Partial least squares structural equation modeling in HRM research. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2020, 31, 1617–1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Mena, J.A. An assessment of the use of partial least squares structural equation modeling in marketing research. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2012, 40, 414–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, W.W. How to write up and report PLS analysis. In Handbook of Partial Least Squares; Vinzi, V.E., Chin, W.W., Henseler, J., Wang, H., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; pp. 655–690. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.; Hollingsworth, C.L.; Randolph, A.B.; Chong, A.Y.L. An updated and expanded assessment of PLS-SEM in information systems research. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2017, 111, 442–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, A.P. Discovering Statistics Using SPSS for Windows: Advanced Techniques for the Beginner; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Stone, M. Cross-Validatory Choice and Assessment of Statistical Predictions. J. R. Stat. Soc. 1974, 36, 111–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geisser, S. A Predictive Approach to the Random Effects Model. Biometrika 1974, 61, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.-T.; Bentler, P.M. Fit Indices in Covariance Structure Modeling: Sensitivity to Underparameterized Model Misspecification. Psychol. Methods 1998, 3, 424–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S.; Islam, T.; D’Cruz, P.; Noronha, E. How Servant Leadership Averts Workplace Bullying: A Moderated-Mediation Examination. Acad. Manag. Proc. 2021, 1, 12805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Ahmad Faraz, N.; Ahmed, F.; Iqbal, M.K.; Saeed, U.; Mughal, M.F.; Raza, A. Curbing nurses’ burnout during COVID-19: The roles of servant leadership and psychological safety. J. Nurs. Manag. 2021, 29, 2383–2391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrade, M.S. Servant leadership: Developing others and addressing gender inequities. Strateg. HR Rev. 2023, 22, 52–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Category | Frequency | % |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Female | 316 | 87.3 |

| Male | 46 | 12.7 |

| Age | ||

| <40 | 178 | 49.2 |

| 40–50 | 92 | 25.4 |

| >51 | 92 | 25.4 |

| Years within a healthcare organization | ||

| <5 | 45 | 12.4 |

| 5–10 | 55 | 15.2 |

| 11–15 | 75 | 20.7 |

| 16–20 | 61 | 16.9 |

| >20 | 126 | 34.8 |

| Construct and Items | Loadings | VIF | α | Composite Reliability | AVE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SL: Servant Leadership | ||||||

| EM: Empowerment | 0.917 | 0.920 | 0.709 | |||

| EM01 | 0.778 | 3.123 | ||||

| EM02 | 0.884 | 2.921 | ||||

| EM03 | 0.862 | 2.138 | ||||

| EM04 | 0.777 | 3.152 | ||||

| EM05 | 0.875 | 2.848 | ||||

| EM06 | 0.868 | 1.905 | ||||

| AC: Accountability | 0.815 | 0.827 | 0.730 | |||

| AC01 | 0.806 | 1.882 | ||||

| AC02 | 0.885 | 4.038 | ||||

| AC03 | 0.870 | 1.904 | ||||

| FO: Forgiveness | 0.880 | 0.880 | 0.807 | |||

| FG01 | 0.901 | 4.655 | ||||

| FG02 | 0.914 | 4.540 | ||||

| FG03 | 0.879 | 3.914 | ||||

| AU: Authenticity | 0.887 | 0.889 | 0.747 | |||

| AU01 | 0.857 | 2.364 | ||||

| AU02 | 0.844 | 2.228 | ||||

| AU03 | 0.885 | 2.776 | ||||

| AU04 | 0.871 | 2.515 | ||||

| HU: Humility | 0.903 | 0.904 | 0.720 | |||

| HU01 | 0.809 | 2.530 | ||||

| HU02 | 0.839 | 2.274 | ||||

| HU03 | 0.852 | 3.976 | ||||

| HU04 | 0.868 | 2.693 | ||||

| HU05 | 0.873 | 2.707 | ||||

| ST: Stewardship | 0.905 | 0.905 | 0.913 | |||

| ST01 | 0.956 | 4.243 | ||||

| ST02 | 0.955 | 3.145 | ||||

| Work Engagement | ||||||

| VI: Vigor | 0.800 | 0.816 | 0.628 | |||

| VI01 | 0.740 | 1.523 | ||||

| VI02 | 0.855 | 1.972 | ||||

| VI03 | 0.849 | 1.906 | ||||

| VI04 | 0.716 | 1.427 | ||||

| DE: Dedication | 0.741 | 0.774 | 0.660 | |||

| DE01 | 0.845 | 1.679 | ||||

| DE02 | 0.883 | 1.791 | ||||

| DE03 | 0.697 | 1.285 | ||||

| AB: Absorption | 0.764 | 0.786 | 0.586 | |||

| AB01 | 0.695 | 1.359 | ||||

| AB02 | 0.844 | 1.689 | ||||

| AB03 | 0.796 | 1.607 | ||||

| AB04 | 0.718 | 1.375 | ||||

| Constructs | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. AC: Accountability | 0.854 | |||||

| 2. AU: Authenticity | 0.768 | 0.881 | ||||

| 3. EM: Empowerment | 0.840 | 0.831 | 0.842 | |||

| 4. FO: Forgiveness | 0.826 | 0.840 | 0.836 | 0.923 | ||

| 5. HU: Humility | 0.817 | 0.824 | 0.887 | 0.858 | 0.858 | |

| 6. ST: Stewardship | 0.776 | 0.803 | 0.794 | 0.785 | 0.773 | 0.955 |

| Construct | Stoner-Geisser Q2 | R2 | GOF | f2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Absorption | 0.369 | 0.379 | 0.373 | 0.611 |

| Dedication | 0.332 | 0.341 | 0.336 | 0.518 |

| Vigor | 0.378 | 0.384 | 0.381 | 0.624 |

| SRMR | 0.062 |

| Relationship | Path Coefficient | t-Value | 95% CIs (Bias Corrected) | Results | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Formation of higher-order variables of Servant Leadership | |||||

| EM → SL | 0.270 *** | 44.316 | [0.258, 0.282] | Supported | |

| AC → SL | 0.136 *** | 30.451 | [0.128, 0.145] | Supported | |

| FO → SL | 0.150 *** | 32.766 | [0.142, 0.161] | Supported | |

| AU → SL | 0.178 *** | 32.812 | [0.167, 0.188] | Supported | |

| HU → SL | 0.232 *** | 40.378 | [0.220, 0.243] | Supported | |

| ST → SL | 0.096 *** | 28.607 | [0.090, 0.103] | Supported | |

| Servant Leadership effect on Work Engagement | |||||

| SL → VI | 0.621 *** | 16.098 | [0.537, 0.687] | Supported | |

| SL → DE | 0.586 *** | 13.991 | [0.496, 0.660] | Supported | |

| SL → AB | 0.616 *** | 16.370 | [0.532, 0.682] | Supported | |

| Relationship | β | t | p | β | t | p | β | t | p | Invariant |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||||||||||

| Female | Female | Female | Male | Male | Male | |||||

| SL → VI | 0.622 | 15.008 | 0.000 | 0.621 | 6.085 | 0.000 | Yes | |||

| SL → DE | 0.586 | 12.830 | 0.000 | 0.605 | 5.959 | 0.000 | Yes | |||

| SL → AB | 0.624 | 15.538 | 0.000 | 0.628 | 6.750 | 0.000 | Yes | |||

| Age | ||||||||||

| <40 | <40 | <40 | 41–50 | 41–50 | 41–50 | >51 | >51 | >51 | ||

| SL → VI | 0.729 | 19.083 | 0.000 | 0.547 | 6.711 | 0.000 | 0.485 | 5.036 | 0.000 | Yes |

| SL → DE | 0.688 | 16.307 | 0.000 | 0.596 | 7.376 | 0.000 | 0.343 | 3.048 | 0.001 | Yes |

| SL → AB | 0.698 | 17.861 | 0.000 | 0.595 | 7.052 | 0.000 | 0.449 | 4.805 | 0.000 | Yes |

| Years within a healthcare organization | ||||||||||

| <10 | <10 | <10 | 10–20 | 10–20 | 10–20 | >20 | >20 | >20 | ||

| SL → VI | 0.572 | 9.609 | 0.000 | 0.760 | 18.522 | 0.000 | 0.456 | 5.215 | 0.000 | Yes |

| SL → DE | 0.565 | 8.053 | 0.000 | 0.724 | 15.617 | 0.000 | 0.403 | 4.687 | 0.000 | Yes |

| SL → AB | 0.581 | 10.023 | 0.000 | 0.751 | 17.883 | 0.000 | 0.470 | 5.492 | 0.000 | Yes |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Malićanin, V.; Čivović, A.; Aničić, A.; Bugarčić, M.; Slavković, M. The Role of Servant Leadership in Work Engagement Among Healthcare Professionals. Healthcare 2025, 13, 2565. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13202565

Malićanin V, Čivović A, Aničić A, Bugarčić M, Slavković M. The Role of Servant Leadership in Work Engagement Among Healthcare Professionals. Healthcare. 2025; 13(20):2565. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13202565

Chicago/Turabian StyleMalićanin, Vesna, Aleksandar Čivović, Ana Aničić, Marijana Bugarčić, and Marko Slavković. 2025. "The Role of Servant Leadership in Work Engagement Among Healthcare Professionals" Healthcare 13, no. 20: 2565. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13202565

APA StyleMalićanin, V., Čivović, A., Aničić, A., Bugarčić, M., & Slavković, M. (2025). The Role of Servant Leadership in Work Engagement Among Healthcare Professionals. Healthcare, 13(20), 2565. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13202565