Abstract

Introduction: Negative behaviors in nursing undermine well-being, erode team cohesion, and jeopardize patient safety. Rooted in systemic stressors—workload, emotional strain, and power imbalances—they have far-reaching effects on job satisfaction and care quality. Objective: To systematically map the scientific evidence on negative behaviors among nurses in healthcare organizations. Methods: A scoping review was conducted using five databases: CINAHL, MEDLINE, Scopus, Psychology & Behavioral Sciences Collection, and RCAAP (for grey literature). The review followed the Joanna Briggs Institute methodology and PRISMA-ScR reporting guidelines. Two independent reviewers conducted data extraction and synthesis. Results: Eighteen studies published between 2017 and 2024 met inclusion criteria from an initial pool of 88 references. Eleven thematic domains emerged: (1) the cycle of violence; (2) victims profile; (3) perpetrator profile; (4) negative behaviors spectrum; (5) negative behaviors prevalence; (6) risk predictors; (7) protective predictors; (8) impact of negative behaviors on nurses; (9) impact of negative behaviors on patients; (10) impact of negative behaviors on healthcare organizations; (11) organizational strategies and the role of the nurse managers. Conclusions: The findings highlight the multidimensional nature of negative behaviors and the variability in how they are defined and assessed. This review highlights the need for conceptual clarity and standardized tools to address negative behaviors in nursing. Nurse managers, as key organizational agents, play a critical role in fostering psychological safety, promoting ethical leadership, and ensuring accountability. System-level strategies that align leadership with organizational values are essential to protect workforce well-being and safeguard patient care.

1. Introduction

Negative behaviors in the nursing profession have been widely documented as an ongoing and global issue [1]. Such behaviors significantly disrupt both formal and informal interpersonal processes that are vital to organizational functioning and healthcare delivery [2]. Rather than isolated instances of individual misconduct, these behaviors are increasingly understood as structural and systemic, deeply embedded in organizational cultures and sustained over time. The literature consistently characterizes them as “endemic” with “deep historical roots”, and as a “global phenomenon” that transcends cultural, institutional and geographic boundaries [1].

The emergence of systematic inquiry into these behaviors dates to the 1980s, with the work of Leymann, who developed the Leymann Inventory of Psychological Terror (LIPT) to categorize 45 forms of hostile workplace behavior. His studies identified healthcare workers—particularly nurses—as especially vulnerable due to rigid professional hierarchies, emotionally demanding environments, and asymmetric power dynamics [3].

Despite decades of empirical research, a coherent and unified conceptual framework remains lacking. The literature offers a variety of overlapping terminologies to describe these behaviors, such as unprofessional attitudes and improper or unacceptable social behaviors [4,5,6,7]. Different frameworks conceptualize negative workplace behaviors in diverse ways. The International Labour Organization (ILO) adopts a broad definition encompassing abuse of power, verbal and sexual harassment, incivility, and ostracism [8]. In contrast, Nemeth et al. focus specifically on nursing, framing these behaviors as harmful relational manifestations with consequences at both the individual and organizational levels [9]. While the ILO perspective emphasizes structural and legal dimensions, Nemeth’s framework highlights interpersonal dynamics within healthcare teams [8]. This review adopts Nemeth’s operational definition due to its conceptual specificity and alignment with the nursing context [9].

The persistence of these behaviors is further explained by theoretical frameworks grounded in organizational sociology. Power-conflict theory, as advanced by Coser and Dahrendorf, posits that hierarchical structures and unequal power distributions inherently generate latent tensions. When unaddressed, these tensions can escalate into aggression and dysfunctional dynamics [10,11].

Building on this foundation, Murray’s concept of silent epidemics adds a critical layer of interpretation by addressing the perpetuation of negative behaviors through processes of normalization, institutional neglect, and underreporting [12]. Together, these frameworks reveal how such behaviors arise from systemic power imbalances and become culturally ingrained as tolerated, even expected, elements of professional socialization [1].

Current scientific evidence describe the existence of four types of negative behavior in the healthcare sector: type (1), criminal intent towards the organization; type (2), from patients, family members, or carers towards the organization’s multidisciplinary team; type (3), inside the organization’s multidisciplinary team; and type (4), involving an aggressor who has a personal relationship with the victim but not with the organization [13]. This study will only focus on negative behaviors that occur among nurses (type 3).

These intra-organizational behaviors can manifest horizontally, between peers of equal hierarchical status (e.g., staff nurse to staff nurse), or vertically, involving unequal power relations (e.g., nurse manager to staff nurse or vice versa) [14].

It is well established that the vitality of any organization fundamentally depends on its human capital [5]. Therefore, healthcare organizations are inherently complex systems ripe for conflict [6,7]. Conflicts often arise from perceived incompatibilities between goals, emotions, or perspectives, and are amplified by the division of tasks, shared responsibilities, and operational interdependence. In healthcare settings, these dynamics are further exacerbated by emotionally charged environments, limited resources, and complex relational networks. Such conditions are intrinsic to organizational life and have traditionally been viewed as threats to team cohesion and productivity [4,5,6,7]. Adverse nursing practice environments are consistently associated with burnout, decreased job satisfaction, and higher turnover intentions among nurses [15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22].

Nurse managers, embedded within the organizational structure, are instrumental in mediating the relationship between negative behaviors and the quality of the nursing work environment. Effective nurse management can foster a culture of psychological safety, mutual respect, and team cohesion [15,16,17]. Conversely, the absence of formal reporting mechanisms, combined with fear of retaliation, enables the perpetuation of harmful behavior and undermines efforts at organizational accountability [23].

Although prior studies have examined specific aspects of negative behaviors in nursing, the literature remains fragmented, with no comprehensive synthesis that consolidates typologies, contributing factors, and measurement approaches into a unified conceptual framework. This gap limits the development of standardized assessment tools and evidence-based organizational interventions.

To address this, we conducted a scoping review focused on negative behaviors among nurses within healthcare organizations, identifying key domains, measurement approaches, and knowledge gaps relevant to research, policy, and clinical practice.

This effort was guided by the following research question: What is the scientific evidence on negative behaviors among nurses in healthcare organizations? The primary objective of this study is to systematically map the available scientific evidence on negative behaviors among nurses in healthcare organizations.

2. Methods

2.1. Design

We conducted a scoping review, a form of knowledge synthesis that employs a systematic and iterative approach to identify and synthetize an existing and emerging body of literature on negative behaviors among nurses. Although a scoping review protocol by Almost et al. was identified, which aimed to explore behaviors within workplace relationships, no scoping reviews were found that focused exclusively on negative behaviors among nurses [24].

The rationale for conducting a scoping review lies in its ability to comprehensively map existing evidence and examine the breadth and diversity of available knowledge. In contrast to systematic reviews, which are typically designed to inform evidence-based clinical guidelines, this approach accommodates a wider range of study designs and information sources—beyond peer-reviewed literature—offering a structured yet flexible framework to assess the current state of evidence and identify gaps for future inquiry [25,26,27].

2.2. Protocol and Registration

Before starting the literature research, this scoping review was brought about by the scoping review protocol registered with the Open Science Framework under the following domain: https://osf.io/y4bng/?view_only=0fd4fd321f4940bd919e7ecea1bc8190 (accessed on 3 May 2025).

2.3. Eligibility Criteria

This scoping review was guided by Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) PCC framework, which is designed to support the development of inclusion criteria and structure the research question for scoping reviews. The PCC acronym stands for population, concept, and context [25,26,27]. For this specific review: population refers to the group of interest; concept focuses on the key phenomenon under investigation; and context defines the setting or environment relevant to the review. The combination of these mnemonics brought force to the review question (“What is the scientific evidence on negative behaviors among nurses in healthcare organizations?”).

The following criteria were included for this review:

Population: studies that focused exclusively on licensed registered nurses employed in public or private healthcare organizations, regardless of their specific nursing category, years of clinical experience, age, gender, academic background, or employment relationship. Only studies in which the sample consisted entirely of nurses were included; studies involving mixed samples (e.g., nurses and other healthcare providers or ancillary staff) were excluded. Nurse managers were included when their roles were explicitly clinical or when they were part of broader nursing teams in practice settings. In contrast, studies focusing solely on nurse faculty, academic nurses, educators, nursing students, nursing assistants, and practical/vocational nurses were excluded, as these groups operate in educational or support roles that differ significantly from the clinical and organizational dynamics experienced by registered nurses in direct patient care.

Concept: studies that address one or more negative behaviors or that discuss the concept of negative behavior. The concept of negative behavior providing the basis for this review consists of a set of work attitudes towards other professionals having the potential to negatively impact individuals and organizations [9]. Within the set of negative behaviors presented above, this scoping review will focus on negative behaviors such as bullying, incivility, ostracism, lateral/horizontal violence, or colleague violence [9,14].

Context: all studies reporting or discussing results from healthcare organizations, covering primary care, as well as hospital and long-term care, regardless of the type of institutions either public or private.

Types of Resources: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed-approach studies and systematic reviews that fitted the defined criteria were considered for inclusion. Although grey literature was considered eligible, no studies were retrieved from RCAAP during the search process.

Given the diversity of terminology historically associated with these phenomena, the time frame for the review was established between 2017 and 2024 to capture the period following a conceptual shift in the literature. This shift was marked by seminal contributions such as Nemeth et al. The influence of this work can be observed in a series of subsequent studies that adopted and further developed this terminology and framework [9].

This scoping review included studies published in English, Portuguese, and Spanish, with no restrictions on their geographical location. The remaining studies published in other languages were not accountable for this review. Those languages’ selection was based on the review team’s language proficiency to ensure accurate interpretation and data extraction.

This framework provides a structured approach for determining eligibility criteria and ensures that the review maintains a broad yet focused exploration of the existing literature (Table 1).

Table 1.

Research Question and PCC.

2.4. Information Sources and Research Strategies

An initial exploratory search was carried out in the CINAHL and MEDLINE databases (accessed via EBSCOhost) to identify pertinent keywords and indexing terms. These databases were selected due to their recognized relevance and comprehensive coverage in nursing-related literature reviews [28].

This scoping review was conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) guidelines [25,26,27,29] (see Supplementary Materials).

A comprehensive search strategy was implemented across five databases: CINAHL, MEDLINE, Psychology & Behavioral Sciences Collection, SCOPUS, and RCAAP. The selection of these databases was based not only on their thematic relevance to the research topic but also on their recognized authority and breadth in indexing high-quality, peer-reviewed literature in the fields of health sciences and nursing—thus supporting a robust and comprehensive evidence base [28].

The previously identified keywords were utilized in rigorous combinations using Boolean operators and truncations, with search equations tailored to the indexing structure of each database. The research was conducted on 16 December 2024. The complete search terms used in the five different databases are found in Table 2.

Table 2.

Research terms and results.

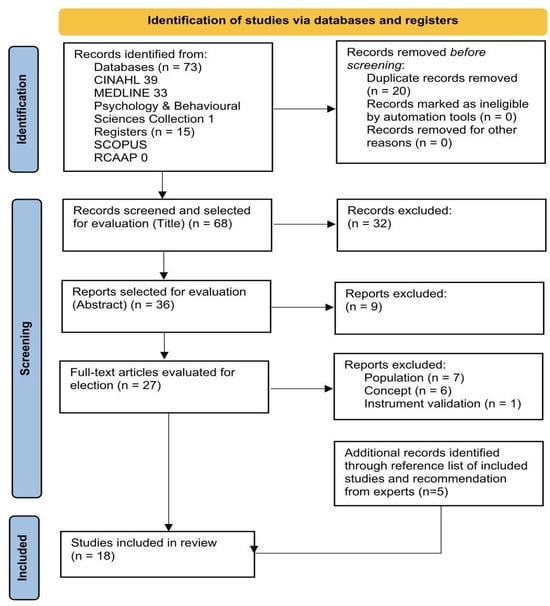

Grey literature was not included due to no relevant results being retrieved in RCAAP. This is reflected in the PRISMA flowchart diagram (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The PRISMA flowchart diagram [29].

2.5. Selection Process

All identified references were organized and imported into the Mendeley reference management software (version 1.19.8), where duplicate records were removed. The remaining studies were then imported into the Rayyan Enterprise and Rayyan Teams+ application (version 1.6.0), for screening [30].

The screening process followed a methodological framework comprising three distinct phases by the same two independent reviewers (NS and RB). In the initial step (1), the literature was screened based on titles and abstracts against the eligibility criteria defined in the review protocol. Studies deemed potentially relevant proceeded to the second phase (2), which involved full-text screening. In the final phase (3), the selected studies were consolidated, and their reference lists were examined using a manual snowballing strategy to identify additional relevant literature [25,26,27,31]. When abstracts lacked sufficient detail to assess eligibility, the full texts were retrieved and thoroughly reviewed to determine inclusion.

Any discrepancies were consensually settled between the reviewers and, when necessary, with the mediation of a third reviewer [25,26,27,31]. The identification, screening, and inclusion of studies were documented using the PRISMA-ScR flowchart diagram, ensuring methodological rigor and transparency consistent with the exploratory objectives of a scoping review [30].

Consistent with the JBI framework for scoping reviews, no critical appraisal of methodological quality was conducted. While this approach aligns with the primary goal of mapping the breadth of scientific evidence, it limits the ability to assess the internal validity of the included studies. This tradeoff was accepted to ensure inclusiveness and capture a wide spectrum of conceptual and contextual data [25].

2.6. Data Collection Process

To extract the data, an Excel file was developed based on the model proposed by the JBI [31].

Data extraction was conducted independently by two reviewers, in line with the methodological approach recommended by JBI guidelines. It was then systematized in a standardized table developed for the purpose of this study [31]. This table was built according to the review’s objective and the respective review question [27], including key information from each source: author(s); year of publication; country of origin; study purpose; sample size (when applicable); type of negative behavior analyzed; data collection instruments (when applicable); methodology adopted; main results; and limitations relevant in the framework of this scoping review.

The discrepancies between the two reviewers were solved during the selection process and data collection process; therefore, consultation with a third reviewer was not necessary.

3. Results

3.1. Screening Results

A total of 88 records were identified through database searches, with 20 being removed due to duplication. Out of 68 records, 32 were excluded after analyzing the titles, resulting in 36 articles for screening by abstract. In the second phase, 9 articles were eliminated based on their abstracts, leading to the selection of 27 articles for full-text evaluation. Of these, 14 articles were excluded because they did not meet the eligibility criteria, due to the inadequacy of the population studied (n = 7), the concept addressed (n = 6), or because they were instrument validation studies (n = 1). A review of the list of references (hand searching) of the included studies and expert recommendations resulted in five additional articles. Thus, a total of 18 records met the eligibility criteria and were included in the synthesis. These steps are synthesized in Figure 1, following the PRISMA flowchart diagram.

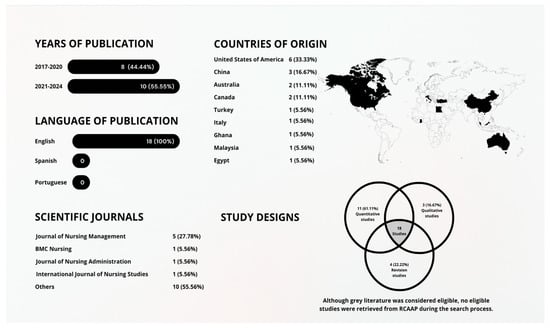

The 18 studies included were published between 2017 and 2024 (44.44% studies published during 2017–2020 and 55.55% published during 2021–2024), and all were written in English (n = 18, 100%). Figure 2 refers to the characteristics of the included studies. In short, these studies were conducted in 8 countries: 14 of them (77.78%) were conducted in high-income countries—United States [32,33,34,35,36,37], Italy [38], Canada [39,40], China [41,42,43] and Australia [1,44]; while the remaining 4 studies (22.22%) were conducted in middle-income and low-income countries—Turkey [45], Ghana [46], Egypt [47], and Malaysia [48].

Figure 2.

Main characteristics of the selected studies.

Out of the included studies, 11 (61.11%) adopted quantitative approaches [32,33,35,38,39,41,42,43,45,46,47], 3 (16.67%) were qualitative studies [1,40], and 4 (22.22%) were integrative reviews [34,36,37,44]. The samples ranged from 13 participants [1] to large groups of more than 1900 nurses [47], totaling 8500 participants for this study. This methodological and geographical heterogeneity offers, therefore, a comprehensive view of negative behaviors (Figure 2).

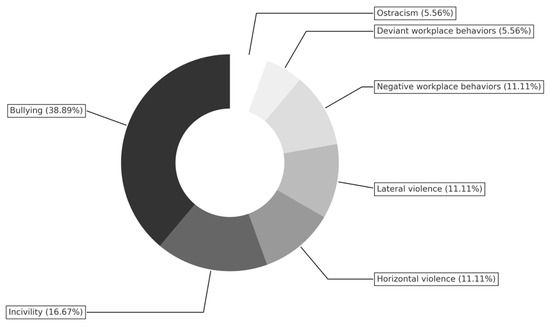

Negative behaviors were analyzed using varied terminologies across the included studies. The term bullying was the most frequently reported, appearing in seven studies (38.89%), followed by incivility in three studies (16.67%), and ostracism in one study (5.56%). Three studies (16.7%) employed broader labels, with two (11.11%) referring to negative workplace behaviors and one (5.56%) to deviant workplace behaviors. Additionally, five studies (27.78%) used peer-specific terminology: lateral violence in two studies (11.11%), horizontal violence in two studies (11.11%), and colleague violence in one study (5.56%). To provide a visual summary of the prevalence of the most reported negative behaviors among nurses across the included studies, a pie chart was constructed (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Prevalence of negative behaviors across the included studies.

To assess negative behaviors, a total of 14 data collection instruments were identified. The Negative Acts Questionnaire-Revised (NAQ-R) was the most frequently reported and utilized, with 6 out of the 18 studies (33.33%) employing this tool in their research [32,35,38,39,45,46].

Regarding the settings, the included studies encompassed various healthcare contexts: eight studies (44.44%) were conducted in a variety from various healthcare settings [32,33,35,36,39,43]; and seven studies (38.89%) were conducted in hospital environments [1,33,40,41,42,44,45], among which four studies (22.22%) focused specifically on acute care settings [1,40,41,44] and one on a public hospital (5.56%) [48].

Table 3(a,b) displays the charted data from each selected study, aligned with the review objective and research question.

Table 3.

(a) Study identification and conceptual focus. (b) Methodological features and main findings.

3.2. Analysis of the Selected Studies

As mentioned, the aim of this scoping review is to systematically map the available scientific evidence on negative behaviors among nurses in healthcare organizations. To meet this objective, 18 studies were included that address the expression of these behaviors within nursing teams, generating the following domains: the cycle of violence; victims profile; perpetrator profile; negative behaviors spectrum; negative behaviors prevalence; risk predictors; protective predictors; impact of negative behaviors on nurses; impact of negative behaviors on patients; impact of negative behaviors on healthcare organizations; and organizational strategies and the role of nurse managers.

3.2.1. The Cycle of Violence

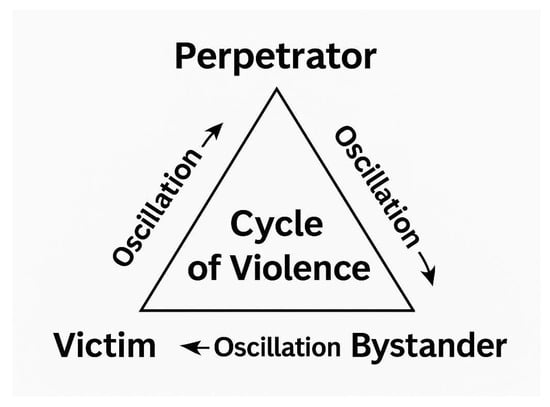

Negative behaviors in nursing often involve fluid roles of victim, perpetrator, and bystander, shaped by contextual pressures and power dynamics. As Edmonson & Zelonka [34] note, these roles shift frequently, especially in high-stress environments.

Bambi et al. [38] found that 32.4% of respondents had experienced both victimization and perpetration, illustrating how individuals may replicate harmful behaviors in response to prior exposure. Hawkins et al. [1] and Krut et al. [40] describe these dynamics as cyclical, where retaliation—such as withholding information or reducing collaboration—emerges as a learned response, reinforcing dysfunctional team patterns.

Trépanier et al. [39] emphasize the role of bystanders, whose silence or inaction can normalize aggression and perpetuate unequal power structures. Their passive complicity often sustains a permissive environment for mistreatment.

These findings underscore the opportunity for meaningful cultural transformation when organizations recognize the systemic roots of negative behaviors and invest in leadership development, team empowerment, and bystander engagement as drivers of a healthier and more supportive work environment [39], as illustrated in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

The cycle of violence.

3.2.2. Victims Profile

Findings from the included studies reveal recurring patterns regarding the profiles of nurses most frequently exposed to negative behaviors. Early-career nurses emerged as a particularly vulnerable group, identified in 33.33% of the studies (6 out of 18), often described in the literature through the expression “nurses are eating their young” [1,35,36,37,40,44]. These professionals commonly report emotional fragility, low self-esteem, and feelings of isolation, especially in workplace cultures marked by an “us versus them” mentality [1,37,44].

Newly hired staff, referenced in 5.56% of the studies (1 out of 18), also appear at increased risk, particularly during the integration phase in unfamiliar teams [1]. Similarly, nurses occupying lower hierarchical positions were reported in 11.11% of the studies (2 out of 18) as more frequently exposed to negative behaviors [1,46]. Only one study (5.56%) highlighted nurses with higher academic qualifications or experience as common targets, potentially due to perceived threats to informal power dynamics within teams [38].

Gender also emerged as a relevant variable. Despite women representing over 89% of the samples across the studies included, 16.67% of studies (3 out of 18) reported that female nurses experienced greater exposure to negative behaviors [31,41,48], suggesting an intersection between gender and organizational vulnerability.

3.2.3. Perpetrator Profile

The characteristics of individuals who perpetrate negative behaviors in nursing settings are multifaceted. Power—whether formal, informal, perceived, or contested—consistently emerges as a central element influencing interpersonal dynamics and the occurrence of such behaviors. In 1 out of the 18 included studies (5.56%), perpetrators were reported to occupy positions of authority within the nursing hierarchy, suggesting that power asymmetries may contribute to the perpetuation of negative behaviors [46].

Individual traits have also been explored. Mansor et al. identify trait anger as a potential contributing factor, although no association was found between negative affectivity and the enactment of negative behaviors, suggesting that emotional predispositions alone may not explain such conduct [48].

Certain behaviors are framed by perpetrators as professionally justified and described by Hawkins et al. as “tough love” or a means to uphold clinical standards and patient safety [1]. Age-related dynamics are observed in both directions, with reports of negative behaviors from older nurses toward younger colleagues and vice versa [31].

Psychological factors have also been reported. Edmonson & Zelonka suggest that some perpetrators may experience low self-confidence and perceive competent peers as threats [34].

Avoidance-based coping strategies, such as psychological withdrawal or rigid separation between personal and professional spheres, may limit team cohesion and indirectly sustain negative behaviors [40].

Table 4 provides a synthesis of the key characteristics associated with victims and perpetrators.

Table 4.

Victims and perpetrators profile.

3.2.4. Negative Behaviors Spectrum

The included studies demonstrate considerable conceptual diversity regarding negative behaviors in nursing settings. Mansor et al. define negative behaviors as unethical actions that violate organizational norms and harm individuals or the work environment. These behaviors range from low-severity forms (e.g., absenteeism, tardiness) to high-severity forms (e.g., theft, harassment, insubordination) and vary by periodicity (sporadic vs. systematic) and by intensity (passive vs. active) [48].

Incivility (addressed in 16.67% of the studies) is described as a low-intensity behavior with ambiguous intent to harm, disrupting interpersonal dynamics. It includes discourtesy, a dismissive tone, and the omission of basic expressions of politeness [33,42]. When persistent and intentional, it may overlap with bullying [36].

Ostracism (addressed in 5.56% of the studies) refers to a subtle social exclusion, such as avoiding interaction, restricting access to common spaces, or relocating individuals to peripheral areas, leading to perceived marginalization [47].

Colleague violence (addressed in 5.56% of the studies) encompasses psychological hostility between colleagues of the same hierarchical level, affecting team cohesion and collaboration [45]. Horizontal violence and lateral violence (addressed in 22.22% of the studies) refer to peer-directed aggression, either overt (e.g., verbal abuse) or covert (e.g., exclusion) [38,40,43].

Bullying (addressed in 38.89% of the studies) is consistently defined by three core elements: intentionality, repetition, and power imbalance. Manifestations include verbal abuse, social exclusion, and spreading rumors. Typologies include person-related, work-related, and physical bullying. Some definitions introduce temporal thresholds, such as weekly episodes over a minimum of six months [34,35,37,38,41,46].

The diversity of terminology found across studies highlights a valuable opportunity to strengthen conceptual coherence in the field. Advancing toward standardized definitions and validated assessment tools will enhance comparability and the quality of future research [45]. As a step in this direction, Table 5 summarizes the types of negative behaviors identified in the included studies, outlining their definitions and key characteristics.

Table 5.

Comparative definitions and characteristics of negative behaviors in nursing.

3.2.5. Negative Behaviors Prevalence

The prevalence of negative behaviors among nurses varies widely, shaped by conceptual definitions, data collection instruments, and contextual factors. Horizontal and colleague violence are notably recurrent. Krut et al. [40] reported that 59.1% of nurses experienced horizontal violence within a six-month period, while Bambi et al. [38] found colleague violence affecting 47% of respondents.

Bullying specifically has been extensively documented as a persistent occupational hazard. Prevalence rates range from 27% to 40%, as observed by Sauer & McCoy [35] and Anusiewicz et al. [37]. Bambi et al. [38] noted that 35.8% of nurses faced negative behaviors, with 42.3% of these exposed to weekly bullying episodes for at least six months. Similar patterns were reported by Lu et al. (30.6%) [41] and Trépanier (40%) [39]. Olender [29] further highlighted the intensity of these behaviors, with 26.3% of nurses reporting daily bullying and 35.9% experiencing it weekly.

3.2.6. Risk Predictors

Organizational antecedents such as high workloads, resource constraints, staff fatigue, and ineffective communication have been associated with increased exposure to incivility and bullying [36]. Excessive workload was also found to be a relevant determinant, though its effect may be attenuated by social support and recognition [39]. Inadequate leadership and suboptimal management, especially in planning and resource distribution, also contribute to the emergence of conflict and interpersonal tension [37].

Through logistic analysis, Bambi et al. identified several predictors of negative interactions: working day shifts, exposure to peer-directed hostility, and previous engagement in negative behaviors [38].

Geographical settings may also play a role. In rural or remote areas, lower turnover rates and sustained interpersonal ties may increase susceptibility to exclusion particularly among newly integrated staff. These dynamics seemed to have been reinforced during the COVID-19 pandemic [1].

3.2.7. Protective Predictors

Working in hospital settings was associated with a lower prevalence of bullying, suggesting that institutional structure may offer a protective effect [38]. Greater professional autonomy was inversely related to incivility [34], and strong work ethic predicted lower levels of negative behaviors [47].

Constructive coping strategies—such as open communication and proactive task adjustment—were associated with reduced interpersonal tension [45]. Social support from colleagues, mentors and external networks emerged as a key factor in mitigating psychological impact [1].

Self-care practices, including physical activity, boundary setting, and distancing from conflict, were reported to enhance emotional regulation [40]. However, their effectiveness appears dependent on broader organizational support. Resilience was noted to be beneficial but insufficient in the absence of engaged leadership and structured psychosocial resources [35].

Institutional policies promoting psychological safety and clear response frameworks were identified as essential to strengthening the overall capacity for conflict prevention and management [32,38].

To illustrate these risks and protective determinants, Table 6 was developed.

Table 6.

Risk and protective predictors.

3.2.8. Impact of Negative Behaviors on Nurses

Negative behaviors are consistently associated with physical and psychological harm among nurses. Early effects include emotional distress, insecurity, cognitive impairment, and low self-confidence [33,35,40,45,47]. Persisting exposure contributes to symptoms such as chronic fatigue, sleep disturbance, gastrointestinal complaints, and headaches [35,40,45].

Among the most critical outcomes is burnout (addressed in 50% of the included studies), a progressive and debilitating syndrome resulting from sustained occupational stress. It is typically characterized by emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and a reduced sense of personal accomplishment. Burnout impairs clinical reasoning, emotional regulation, and relational engagement, ultimately affecting both individual functioning and team dynamics [33,35,37].

Moreover, Bambi et al. reported that 59% of nurses subjected to negative behaviors experienced psychophysical harm [38]. In advanced stages, prolonged exposure may evolve into severe psychopathological states such as major depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, and psychache—an intense form of psychological pain driven by humiliation, despair, and emotional breakdown [39,41,46]. Lu et al. found that negative behaviors were significantly associated with suicidal ideation and suicide attempts [41]

These adverse effects often extend into nurses’ personal lives, increasing the risk of interpersonal conflict, substance misuse, and persistent psychological rumination [31,35,45]. As reported by Hawkins et al., the emotional toll of workplace mistreatment often extended beyond the clinical setting, with participants describing severe psychological spillover into their personal lives. This was vividly illustrated through qualitative narratives in which some nurses referred to their experiences as “living hell” [1].

3.2.9. Impact of Negative Behaviors on Patients

The psychological burden experienced by nurses impairs clinical vigilance, judgment, and communication, particularly in high-acuity settings [35,37]. Anusiewicz et al. observed associations between exposure to mistreatment and increased rates of medication errors and patient falls. Emotional exhaustion and cognitive overload compromise decision making and delay interventions [37].

Hostile work environments weaken communication among team members, diminishing collective responses during emergencies [35]. As emphasized by Sauer & McCoy, these dynamics reduce collaborative capacity and elevate the risk of adverse events [35]. Ultimately, poor practice environments compromise patient safety, satisfaction, and dignity [33].

3.2.10. Impact of Negative Behaviors on Healthcare Organizations

At the organizational level, negative behaviors undermine retention, efficiency, and performance. Toxic work environments contribute to elevated attrition rates and intra-organizational transfers [1,34,36,37,38,39,44,46]. Bambi et al. reported that 21.9% of nurses experiencing mistreatment intended to exit the profession and 20% sought reassignment [38].

Although some nurses compensate for negative behaviors with increased productivity, these efforts are often unsustainable and lead to emotional exhaustion [45]. Xiaolong et al. found that incivility negatively impacts polychronicity, defined as the individual tendency to engage in multiple tasks simultaneously. This exposure weakens the positive association between polychronicity and job satisfaction, leading even highly adaptable nurses to experience emotional fatigue and disengagement [42].

Challenging work environments may also entail considerable financial implications. Edmonson & Zelonka estimated that issues related to workplace dynamics, including turnover and decreased care quality, can result in annual costs ranging from USD 4 to 7 million per hospital in the United States. In addition, team disruption and staffing fluctuations can affect continuity of care, influence performance metrics, and impact the institution’s public perception [34].

Table 7 summarizes the reported impacts of negative behaviors across multiple levels, including nurses, patients, and healthcare organizations.

Table 7.

Impacts of negative behaviors.

3.2.11. Organizational Strategies and the Role of Nurse Managers

The reviewed studies indicated that organizational context influences both the prevalence of negative behaviors and the capacity of nurse managers to address them effectively. Leadership practices do not operate in isolation but are shaped by institutional culture, available resources, and systemic support mechanisms.

Organizations that promote autonomy, emotional support, and open communication are consistently associated with lower levels of incivility and interpersonal conflict [33]. Smith et al. found that such environments reported fewer episodes of mistreatment [33], while Olender observed that staff exposed to engaged and supportive nurse managers reported reduced hostility [32].

In contrast, authoritarian or top-down leadership models appear to contribute to workplace tension. Farrell reported that hierarchical structures may reinforce power imbalances and limit open dialogue, reducing psychological safety and hindering conflict resolution [36].

Several studies highlighted the importance of leadership-led interventions supported at the organizational level. Hawkins et al. emphasized the role of nurse managers in advancing respectful and safe work environments, noting the need for multi-level strategies anchored in leadership [44]. Farrell proposed a framework that includes early identification of incivility, elimination of behavioral triggers, professional development, and the use of cognitive rehearsal techniques [36].

Policy-oriented approaches were described by Edmonson & Zelonka, who outlined steps for implementation including: recognizing the problem, mitigating aggravating factors such as overload and fatigue, training leaders in communication, enforcing behavioral standards, and promoting accountability among staff [34].

Bambi et al. recommended continuing education, anonymous reporting systems, access to occupational psychologists, and rotation of team compositions as organizational strategies to reduce interpersonal strain [38].

Despite these efforts, some barriers to implementation were noted across studies. These include fear of retaliation, limited confidence, managerial inaction, time constraints, and the perceived indispensability of certain staff members [29,31,34,36,39,43].

Table 8 was developed to present strategies to prevent and address negative behaviors among nurses.

Table 8.

Strategies to prevent and address negative behaviors among nurses.

4. Discussion

The present scoping review synthesized findings from 18 studies, highlighting the multidimensional nature of negative behaviors among nurses.

The eleven domains identified in this review—ranging from typologies and prevalence to protective predictors and organizational strategies—should not be interpreted in isolation. Rather, they constitute an interdependent framework in which individual, relational, and systemic variables interact recursively to shape the manifestation and persistence of negative behaviors in nursing environments.

These behaviors span a continuum of incivility, ostracism, bullying, and lateral violence and are deeply embedded in organizational and interpersonal dynamics. The results confirm the persistence and complexity of these phenomena, aligning with existing literature that positions them as systemic rather than isolated issues [49,50,51].

One of the most salient findings is the cyclical nature of mistreatment within nursing teams, where individuals alternate between roles of victim, perpetrator, and bystander [38]. These roles are often shaped by exposure to organizational stressors, socialization processes, and power asymmetries. Several studies described how such patterns become normalized over time, particularly in environments that tolerate aggression under the guise of disciplinary action or “tough love” [1,52]. This aligns with the concept of “organizational Darwinism”, wherein emotional detachment and competitiveness are inadvertently reinforced by hierarchical structures [53,54].

Professional seniority does not provide uniform protection. While novice and early-career nurses remain the most frequent targets [1,38,49,51,55,56], several studies reported that mid-career professionals and nurse managers may also experience negative behaviors, often related to informal power struggles or perceived threats to group cohesion [1,37,41,44]. The circularity of roles, where those previously victimized may later perpetuate similar behaviors, illustrates how negative behaviors can perpetuate themselves across generations of professionals [41,54].

The role of bystanders emerged as a critical factor in either reinforcing or mitigating harmful behaviors. Passive or avoidant bystanders contribute to normalization of mistreatment, while active or suppressive bystanders may help to reshape team norms [39,50]. These findings underscore the importance of fostering collective accountability and cultivating workplace cultures where interventions are encouraged and supported.

Another important observation was the inconsistency in terminology and conceptual frameworks across the studies. Studies used multiple overlapping terms, despite key differences in severity, intentionality, and duration [32,38,40,41,44,46,57]. This lack of standardization complicates measurement and intervention [49,55,58]. These challenges echo those previously reported, which identified up to 13 distinct terms describing similar workplace phenomena [59].

Contrary to isolated findings suggesting hospital settings may offer protection [38], the broader evidence shows that negative behaviors are more likely to occur in hospital-based contexts [57,60,61,62], especially in high-pressure units. Emergency departments [60,63], operating rooms [62], surgical wards [64,65], oncology units [66,67], and correctional facilities [68] were consistently associated with increased exposure to mistreatment.

Our review identified several risk factors associated with negative behaviors, which are also reflected in the existing literature. For example, maladaptive coping strategies such as avoidance and substance use have been highlighted by João & Portelada [23], while Jang et al. [51] emphasized the role of low emotional intelligence and strong meritocratic beliefs in reinforcing such behaviors within performance-oriented cultures.

Burnout was identified as both a key outcome and a mediating mechanism. Defined by Maslach et al. [69], it was consistently linked to bullying, chronic stress, and disengagement [33,34,35,36,37,38,39,44,46,70,71]. João et al. found nearly 70% of bullied nurses are at moderate or high burnout risk [72]. Ultimately, burn-on was described as a state of persistent emotional exhaustion masked by continued functionality [73].

Institutional commitment to zero-tolerance policies appears to be increasingly framed in the literature as essential for long-term workforce sustainability [34,35,38,44,51,52]. Supportive leadership—underpinned by emotional intelligence, psychological safety, and conflict management skills—emerged as a key protective factor [51]. Interventions like coaching, cognitive rehearsal, and nonviolent communication showed promise [35,74], yet several authors noted that many managers lack these competencies, often defaulting to avoidance or punitive strategies that exacerbate toxic dynamics [1,34].

Hopefully, our study unveiled multiple protective factors closely aligned with international evidence emphasizing the buffering effect of supportive environments [33,47]. The iceberg model of competencies offers a valuable lens: while surface-level skills like clinical expertise are often prioritized, hidden competencies—emotional intelligence, ethical reasoning, conflict mediation—are decisive in shaping culture [75].

To break these cycles, organizations must move beyond surface-level interventions and cultivate environments where psychological safety and collaborative competence are valued as much as clinical expertise [75]. These findings suggest that addressing negative workplace behaviors requires multi-level strategies.

Certain expressions cited in this review (e.g., “a living hell”, “nurses eating their young” [1]) were directly quoted from original studies to faithfully illustrate participants’ experiences and the language used in qualitative data. While vivid, these phrases were interpreted within a neutral analytical framework and do not reflect editorial bias.

Ultimately, power-conflict theory frames negative behaviors as outcomes of unresolved tensions and systemic asymmetries [10,11]. Addressing them requires aligning leadership with organizational structures. While nurse managers are pivotal in fostering safe environments, their effectiveness depends on the systems that support them. Sustainable change stems not from isolated actions but from integrated strategies that promote psychological safety, accountability, and relational care. In doing so, we move from “us versus them” to a culture of “we care together.”

5. Limitations and Future Prospects

This review presents several limitations that may affect the possibility of generalizing its findings. The selection of four databases and the inclusion of studies published exclusively in English, Portuguese, or Spanish may have introduced language and publication bias, potentially omitting relevant evidence from other linguistic or regional contexts.

The included studies used diverse and, at times, overlapping terminology to describe negative behaviors (e.g., bullying, incivility, lateral violence). While this conceptual heterogeneity complicates direct comparison, it also reflects the current fragmentation in the field and reinforces the need for standardized definitions.

Although validated tools such as the Nursing Incivility Scale and the Negative Behaviors in Healthcare Survey are commonly used in the field, studies employing these instruments may have been underrepresented in our results due to limitations in indexing and search string specificity. In this review, we deliberately adopted the term “nurses” alongside complementary descriptors of negative behaviors to ensure thematic focus. Nonetheless, we acknowledge that incorporating broader or truncated terms (e.g., “nursing”, “nurs*”, “registered nurs*”) could have enhanced the sensitivity of the search. Future reviews should consider such refinements to maximize retrieval scope and inclusiveness.

As noted in the methodology, and in line with JBI guidance, no critical appraisal was performed, which although appropriate for a scoping review limits assessment of evidence rigor. The findings should therefore not be assumed to derive solely from high-quality studies; acknowledging this enhances transparency and scientific integrity.

Future research should prioritize longitudinal, quasi-experimental, and mixed-methods designs to evaluate the effectiveness of leadership-based and educational interventions. Emphasis should be placed on measurable outcomes such as burnout, turnover, missed nursing care, and patient safety.

Special attention should be given to vulnerable populations—namely newly graduated nurses—and to the implementation of safe reporting mechanisms. The integration of qualitative approaches, such as interviews and ethnographic methods, will enable a more comprehensive understanding of the organizational and cultural dimensions that sustain negative behaviors.

6. Conclusions

This scoping review confirms that negative behaviors among nurses are not isolated incidents but persistent and systemic phenomena with serious consequences for workforce sustainability and patient safety. Nurse managers and healthcare leaders must move beyond reactive interventions and invest in long-term strategies that promote psychological safety, conflict literacy, and ethical leadership. Institutional commitment to zero tolerance, structured reporting, and leadership development is no longer optional—it is an urgent imperative.

Healthcare institutions must recognize negative workplace behaviors not merely as interpersonal issues but as systemic threats to workforce sustainability and care quality—requiring structural responses, not just individual interventions.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/healthcare13162079/s1, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) Checklist.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.S., R.B., P.C. and E.N.; methodology, N.S., R.B. and E.N.; software, N.S., R.B. and E.N.; formal analysis, N.S., R.B. and E.N.; investigation, N.S., R.B. and E.N.; resources, N.S., R.B. and E.N.; data curation, N.S., R.B. and E.N.; writing—original draft preparation, N.S., R.B., P.C. and E.N.; writing—review and editing, N.S., R.B., P.C. and E.N.; visualization, N.S., R.B., P.C. and E.N.; supervision, N.S., R.B., P.C. and E.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Hawkins, N.; Jeong, S.Y.S.; Smith, T.; Sim, J. A conflicted tribe under pressure: A qualitative study of negative workplace behavior in nursing. J. Adv. Nurs. 2022, 79, 711–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McPherson, P.; Buxton, T. In their own words: Nurses countering workplace incivility. Nurs. Forum 2019, 54, 455–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leymann, H. Mobbing and psychological terror at workplaces. Violence Vict. 1990, 5, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- João, A.L. Mobbing/Agressão Psicológica na Profissão de Enfermagem; Lusociência: Lisbon, Portugal, 2013; ISBN 9789728930882. [Google Scholar]

- Chiavenato, I. Recursos Humanos: O Capital Humano das Organizações, 11th ed.; Atlas: São Paulo, Brazil, 2020; ISBN 9788597023671. [Google Scholar]

- Huston, C.J. Leadership Roles and Management Functions in Nursing: Theory and Application, 11th ed.; Wolters Kluwer: Alphen aan den Rijn, The Netherlands, 2024; ISBN 9781975193089. [Google Scholar]

- Rahim, M.A. Managing Conflict in Organizations, 5th ed; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2023; ISBN 9781032258201. [Google Scholar]

- Safe and Healthy Working Environments Free from Violence and Harassment. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/publications/safe-and-healthy-working-environments-free-violence-and-harassment (accessed on 20 December 2024).

- Nemeth, L.S.; Stanley, K.M.; Martin, M.M.; Mueller, M.; Layne, D.; Wallston, K.A. Lateral violence in nursing survey: Instrument development and validation. Healthcare 2017, 5, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coser, L.A. The Functions of Social Conflict; Routledge: Oxon, UK, 1956; ISBN 9780415176279. [Google Scholar]

- Dahrendorf, R. Class and Class Conflict in Industrial Society; Stanford University Press: Stanford, CA, USA, 1959. [Google Scholar]

- Murray, J.S. Workplace bullying in nursing: A problem that can’t be ignored. Medsurg Nurs. 2009, 18, 273–276. [Google Scholar]

- Workplace Violence. Available online: https://www.nursingworld.org/practice-policy/advocacy/state/workplace-violence2/ (accessed on 20 December 2024).

- Layne, D.M.; Nemeth, L.S.; Mueller, M.; Wallston, K.A. The Negative Behaviours in Healthcare Survey: Instrument development and validation. J. Nurs. Meas. 2019, 27, 221–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, G.; Lucas, P.; Gaspar, F. International portuguese nurse leaders’ insights for multicultural nursing. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 12144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, P.; Jesus, É.; Almeida, S.; Araújo, B. Relationship of the nursing practice environment with the quality of care and patients’ safety in primary health care. BMC Nurs. 2023, 22, 413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, D.; Figueiredo, A.R.; Lucas, P. Nurses’ Well-Being at Work in a Hospital Setting: A Scoping Review. Healthcare 2024, 12, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, P.; Sousa, J.P.; Nascimento, T.; Cruchinho, P.; Nunes, E.; Gaspar, F.; Lucas, P. Leadership Development in Undergraduate Nursing Students: A Scoping Review. Nurs. Rep. 2025, 15, 160–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, G.; Cheng, B.; Tian, J.; Ma, J.; Gong, C. Effects of negative workplace gossip on unethical work behavior in the hospitality industry: The roles of moral disengagement and self-construal. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2021, 31, 290–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luongo, J.; Freitas, G.F.; Fernandes, M.F.P. Caracterização do assédio moral nas relações de trabalho: Uma revisão da literatura. Cult. Cuid. 2011, 15, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. Health at a Glance 2023: OECD Indicators; OECD Publishing: Paris, França, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Council of Nurses. International Nurses Day 2024: The Economic Power of Care; International Council of Nurses: Geneva, Suíça, 2024; Available online: https://www.icn.ch/resources/publications-and-reports/international-nurses-day-2024-report (accessed on 3 May 2025).

- João, A.L.; Portelada, A. Coping with workplace bullying: Strategies employed by nurses in the healthcare setting. Nurs. Forum 2023, 23, 8447804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almost, J.; Wolff, A.; Mildon, B.; Price, S.; Godfrey, C.; Robinson, S.; Ross-White, A.; Mercado-Mallari, S. Positive and negative behaviours in workplace relationships: A scoping review protocol. BMJ Open 2015, 5, e007685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aromataris, E.; Lockwood, C.; Porritt, K.; Pilla, B.; Jordan, Z. JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis; JBI: Adelaide, Australia, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.D.J.; Marnie, C.; Colquhoun, H.; Garritty, C.M.; Hempel, S.; Horsley, T.; Langlois, E.V.; Lillie, E.; O’Brien, K.K.; Tunçalp, Ö.; et al. Scoping reviews: Reinforcing and advancing the methodology and application. Syst. Rev. 2021, 10, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.; Godfrey, C.M.; Khalil, H.; McInerney, P.; Parker, D.; Soares, C.B. Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. Int. J. Evid. Based Health 2015, 13, 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subirana, M.; Solà, I.; Garcia, J.M.; Gich, I.; Urrútia, G. A nursing qualitative systematic review required MEDLINE and CINAHL for study identification. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2005, 58, 20–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 69, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouzzani, M.; Hammady, H.; Fedorowicz, Z.; Elmagarmid, A. Rayyan: A web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst. Rev. 2016, 5, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollock, D.; Peters, M.D.; Khalil, H.; McInerney, P.; Alexander, L.; Tricco, A.C.; Evans, C.; de Moraes, E.B.; Godfrey, C.M.; Pieper, D.; et al. Recommendations for the extraction, analysis, and presentation of results in scoping reviews. JBI Évid. Synth. 2022, 21, 520–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olender, L. The Relationship Between and Factors Influencing Staff Nurses’ Perceptions of Nurse Manager Caring and Exposure to Workplace Bullying in Multiple Healthcare Settings. J. Nurs. Adm. 2017, 47, 501–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, J.G.; Morin, K.H.; Lake, E.T. Association of the nurse work environment with nurse incivility in hospitals. J. Nurs. Manag. 2017, 26, 219–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edmonson, C.; Zelonka, C. Our own worst enemies: The nurse bullying epidemic. Nurs. Adm. Q. 2019, 43, 274–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sauer, P.A.; McCoy, T.P. Nurse Bullying: Impact on Nurses’ Health. West. J. Nurs. Res. 2016, 39, 1533–1546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrell, J.A. Empowering nurses to build a culture of civility. J. Radiol. Nurs. 2022, 41, 136–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anusiewicz, C.V.; Shirey, M.R.; Patrician, P.A. Workplace bullying and newly licensed registered nurses: An evolutionary concept analysis. Work. Health Saf. 2019, 67, 250–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bambi, S.; Guazzini, A.; Piredda, M.; Lucchini, A.; De Marinis, M.G.; Rasero, L. Negative interactions among nurses: An explorative study on lateral violence and bullying in nursing work settings. J. Nurs. Manag. 2019, 27, 749–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trépanier, S.G.; Peterson, C.; Fernet, C.; Austin, S.; Desrumaux, P. When workload predicts exposure to bullying behaviours in nurses: The protective role of social support and job recognition. J. Adv. Nurs. 2021, 77, 3093–3103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krut, B.A.; Laing, C.M.; Moules, N.J.; Estefan, A. The impact of horizontal violence on the individual nurse: A qualitative research study. Nurse Educ Pr. 2021, 54, 103079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.E.; Sun, M.; Li, Y.; Wu, L.; Zhang, X.; Wang, J.; Huang, Y.; Cao, F. Association of workplace bullying with suicide ideation and attempt among Chinese nurses during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Clin. Psychol. Med. Settings 2023, 30, 687–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiaolong, T.; Gull, N.; Asghar, M.; Jianmin, Z. The relationship between polychronicity and job-affective well-being: The moderator role of workplace incivility in healthcare staff. Work 2021, 70, 1267–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, X.; Gan, Y.; Zeng, Q.; Xiong, L.; Zhang, F.; Xiong, H.; Chang, H.; Chen, Y.; Guan, C.; Wang, J.; et al. Nurse-to-nurse horizontal violence in Chinese hospitals and the protective role of head nurse’s caring and nurses’ group behaviour: A cross-sectional study. J. Nurs. Manag. 2022, 30, 1590–1599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hawkins, N.; Jeong, S.; Smith, T. New graduate registered nurses’ exposure to negative workplace behaviour in the acute care setting: An integrative review. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2019, 93, 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayakdaş, D.; Arslantaş, H. Colleague violence in nursing: A cross-sectional study. J. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2018, 9, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dapilah, E.; Druye, A.A. Investigating workplace bullying (WPB), intention to quit and depression among nurses in the Upper West Region of Ghana. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0305026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elliethey, N.S.; Hashish, E.A.A.; Elbassal, N.A.M. Work ethics and its relationship with workplace ostracism and counterproductive work behaviours among nurses: A structural equation model. BMC Nurs. 2024, 23, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansor, M.; Ibrahim, R.M.; Afthanorhan, A.; Salleh, A.M.M. The mechanism of anger and negative affectivity on the occurrence of deviant workplace behavior: An empirical evidence among Malaysian nurses in public hospitals. Belitung Nurs. J. 2022, 8, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Ryu, Y.M.; Yu, M.; Kim, H.; Oh, S. A Qualitative Meta-Synthesis of Studies on Workplace Bullying among Nurses. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 14120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.; Choi, S.S.W.; Im, C. Exploring Bystander Behavior Types as a Determinant of Workplace Violence in Nursing Organizations Focusing on Nurse-To-Nurse Bullying: A Qualitative Focus Group Study. J. Nurs. Manag. 2024, 1, 4653042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, S.J.; Son, Y.-J.; Lee, H. Intervention types and their effects on workplace bullying among nurses: A systematic review. J. Nurs. Manag. 2022, 30, 1788–1800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartin, P.; Birks, M.; Lindsay, D. Bullying in nursing: How has it changed over 4 decades? J. Nurs. Manag. 2020, 28, 1619–1626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desharnais, B.; Benton, L.; Ramirez, B.; Smith, C.; DesRoches, S.; Ramirez, C.L. Healthy Workplaces for Nurses: A Review of Lateral Violence and Evidence-Based Interventions. J. Appl. Bus. Econ. 2023, 25, 157–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.H.; Choi, E.H. The cycle of verbal violence among nurse colleagues in South Korea. J. Interpers. Violence 2022, 37, NP3107–NP3129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baek, G.L.; Lee, E. Impact of workplace bullying and resilience on new nurses’ turnover intention in tertiary hospitals. Nurs. Health Sci. 2022, 24, 801–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goh, H.S.; Hosier, S.; Zhang, H. Prevalence, Antecedents, and Consequences of Workplace Bullying among Nurses—A Summary of Reviews. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 8256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hampton, D.; Tharp-Barrie, K.; Kay Rayens, M. Experience of nursing leaders with workplace bullying and how to best cope. J. Nurs. Manag. 2019, 127, 30–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, L.; Hsiao, L.P.; Fang, S.H.; Chen, B.C. Effects of assertiveness and psychosocial work condition on workplace bullying among nurses: A cross-sectional study. Int. J. Nurs. Pract. 2020, 26, e12806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, K.; Francis, K.; Tori, K. Variability of terminology used to describe unwanted workplace behaviors in nursing: A scoping review. West. J. Nurs. Res. 2025, 47, 423–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maddineshat, M.; Oshvandi, K.; Sadati, A.K.; Rosenstein, A.H.; Moayed, M.S.; Khatiban, M. Nurses’ perception of disruptive behaviors in emergency department healthcare teams: A qualitative study. Int. Emerg. Nurs. 2021, 55, 100962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahm, G.; Rystedt, I.; Wilde-Larsson, B.; Nordstrom, G.; Strandmark, K.M. Workplace bullying among healthcare professionals in Sweden: A descriptive study. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 2019, 33, 582–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu-Mei, Y. Workplace bullying among operating room nurses in China: A cross-sectional survey. Perspect. Psychiatr. Care 2020, 57, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parizad, N.; Hassankhani, H.; Rahmani, A.; Mohamnadi, E.; Lopez, V.; Cleary, M. Nurses ‘experiences of unprofessional behaviors in the emergency department: A qualitative study. Nurs. Health Sci. 2017, 20, 54–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keller, S.; Yule, S.; Zagarese, V.; Parker, S.H. Predictors and triggers of incivility within healthcare teams: A systematic review of the literature. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e035471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ostroff, C.; Benincasa, C.; Rae, B.; Fahlbusch, D.; Wallwork, N. Eyes on incivility in surgical teams: Teamwork, well-being, and an intervention. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0295271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gosselin, T.K.; Ireland, A.M. Addressing incivility and bullying in the Practice Environment. Semin. Oncol. Nurs. 2020, 36, 151023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis-Pierre, L.; Anglade, D.; Saber, D.; Gattamorta, K.A.; Piehl, D. Evaluating horizontal violence and bullying in the nursing workforce of an oncology academic medical center. J. Nurs. Manag. 2019, 27, 1005–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephenson, A.; Bell, N. Finding meaningful work in difficult circumstances: A study of prison healthcare workers. Health Serv. Manag. Res. 2019, 32, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslach, C.; Schaufeli, W.B.; Leiter, M.O. Job burnout. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2001, 52, 397–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, M.; Han, J.; Qiao, Y.; Wang, J.; Jiang, M.; Zhang, M. Latent classes of personality traits and their relationship with workplace bullying among Acute and Critical Care nurses. J. Nurs. Manag. 2024, 2024, 3238636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.E.; Seo, J.K.; Macphee, M. Effects of workplace incivility and workload on nurses work attitude: The mediating effect of burnout. Int. Nurs. Rev. 2024, 71, e12974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- João, A.L.; Vicente, C.; Portelada, A. Burnout and its correlation with workplace bullying in Portuguese nurses. J. Hum. Behav. Soc. Environ. 2022, 33, 940–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsiao, S.T.S.; Ma, S.C.; Guo, S.L.; Kao, C.C.; Tsai, J.C.; Chung, M.H.; Huang, H.C. The role of workplace bullying in the relationship between occupational burnout and turnover intentions of clinical nurses. Appl. Nurs. Res. 2022, 68, 151483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.K.; Lee, K.S. Factors Associated with Quality of Life of Clinical Nurses: A Cross-Sectional Survey. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 1752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Zhu, W.; Boonyamalik, P.; Powwattana, A.; Zhang, B.; Sun, J. Exploring nursing assistants’ competencies in pressure injury prevention and management in nursing homes: A qualitative study using the iceberg model. BMC Nurs. 2025, 24, 333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).