Physical Therapists’ Use of Behavior Change Strategies to Promote Physical Activity for Individuals with Neurological Conditions

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Qualitative Approach and Research Paradigm

2.2. Research Team Characteristics and Reflexivity

2.3. Context

2.4. Sampling Strategy

2.5. Data Collection Methods

2.5.1. Observations of Physical Therapist–Patient Clinical Encounters

2.5.2. Semi-Structured Interviews

2.6. Data Processing and Analysis

2.6.1. Observations of Physical Therapist–Patient Clinical Encounters

2.6.2. Semi-Structured Interviews with the Physical Therapists

2.7. Techniques to Enhance Trustworthiness

3. Results

3.1. Study Participant Characteristics

3.2. Agreement Data

3.3. Aim 1: Characterization of BCT Use During Observations of Clinical Encounters

3.3.1. Observations

3.3.2. Behavior Change Strategies Reported During Interviews

3.4. Aim 2: Physical Therapists’ Perspectives Regarding Promoting Home-Based Physical Activity After Discharge from Outpatient Services

- (i)

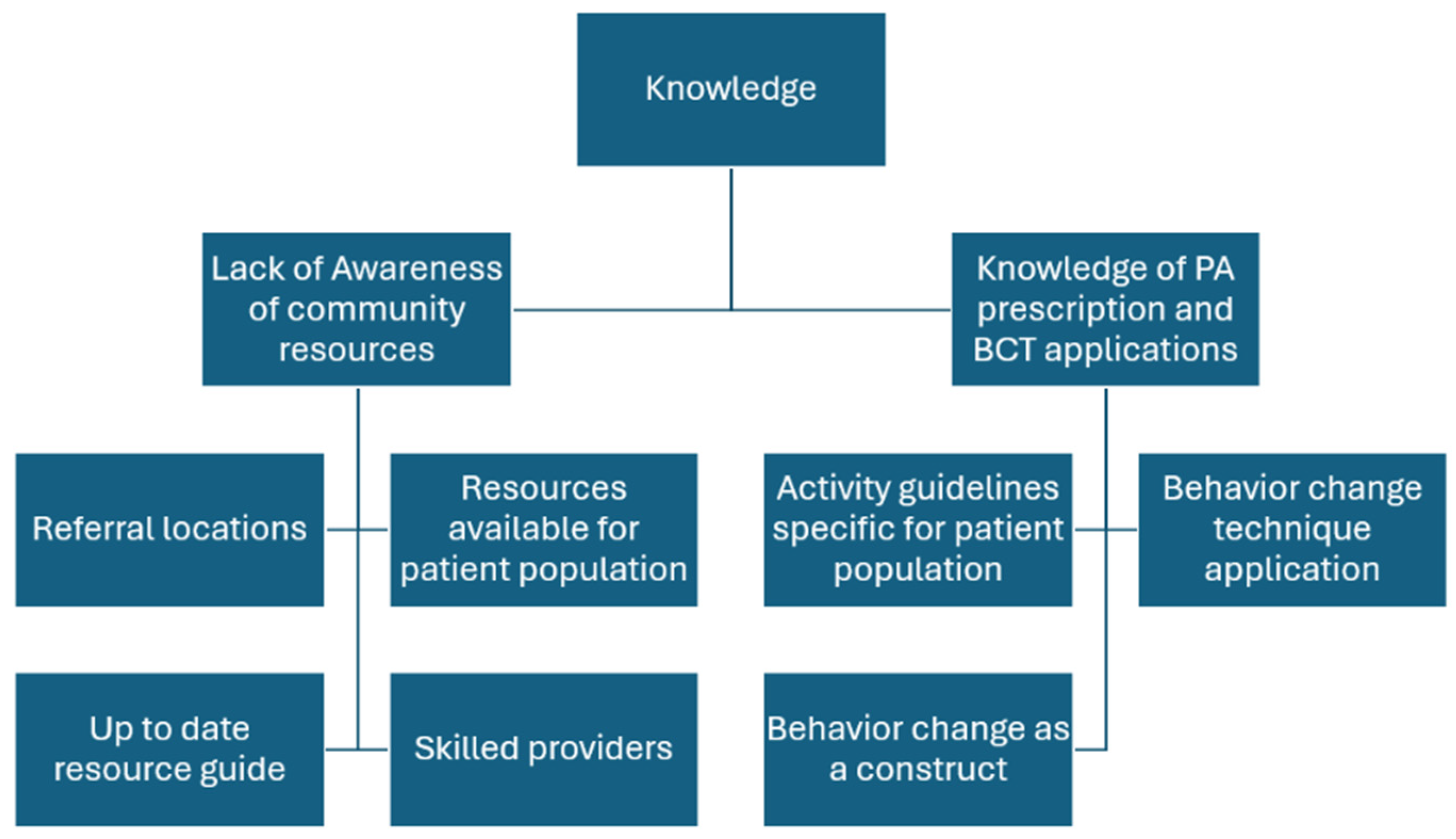

- Knowledge: Two themes aligned with knowledge: (i) awareness of community resources and (ii) knowledge of PA prescription and BCT applications.

- a.

- Lack of awareness of community resources: Participants noted a lack of awareness of up-to-date community resources and referrals, particularly for patients living in areas unfamiliar to the participants. While the hospital network did have options for referrals such as adaptive sports or community gyms, therapists expressed that options for referrals are often spread by word of mouth. Overall, therapists share the perspective that there is a lack of knowledge regarding up-to-date, accessible, and specialized services as referral sources to promote PA after discharge.

- b.

- Limited knowledge of PA prescription and BCT applications: Therapists noted their knowledge of population-specific PA prescription was limited. While therapists mentioned general guidelines (American Heart Association or CDC), these did not always seem suitable for the neurological population. Furthermore, while therapists reported using general strategies to promote PA during practice (e.g., education, social support, goal setting), their knowledge regarding behavior change and specific techniques was limited.

- (ii)

- Memory, Attention, and Decision Processes: One theme aligned with this domain, clinical decision-making.

- a.

- Clinical decision-making impacts how PA is promoted: Participants discussed using information regarding patients’ diagnosis, body systems (e.g., cognition, strength, balance), activity level (e.g., community ambulator), and participation (e.g., social roles) to guide recommendations of PA in the home/community setting. Impairments that impacted safety and fall risk such as balance and cognition were viewed as concerns when promoting PA that would impact the level of difficulty and type of PA promoted. Acuity of diagnosis impacted how PA promotion was approached. For example, three of the therapists mentioned they believed their patients experienced fear and anxiety regarding managing a new injury or diagnosis independently, which is heightened when discharging from outpatient physical therapy as the last structured rehabilitation after an acute injury or event. This makes it more important to promote an independent activity plan at home to help manage this anxiety. This differs from the approach to individuals with chronic conditions, where it is expected they are already managing more independently.

- (iii)

- Professional role: Two themes were linked to professional role, (i) views on the physical therapist role in health promotion and wellness services and (ii) views on the physical therapist role in community activity and participation.

- a.

- Physical therapy has a limited role in health promotion and wellness: Therapists all recognized the importance of activity in this population and the increased risk of inactivity and secondary consequences that individuals with neurological conditions have. However, the majority had the perspective that engaging in prolonged PA in the home and community was an unskilled service and/or fell under the role of personal trainers.

- b.

- PT role is for education not motivation for community activity and participation: All therapists felt that it was part of their role to help their patients with community integration, and it was connected to a sense of fulfillment that therapists had in their profession in two of the interviews. Community integration might include things such as returning to work, socializing, or getting involved with community groups. While this did occasionally have an overlap with increasing activity levels, it was not directly related. In terms of promoting community or home-based activity, all therapists felt it was part of their role to educate patients on activities and provide resources to be active. However, therapists put responsibility for the motivation and follow-through of these activities on the patient.

- (iv)

- Beliefs about capabilities: There was one theme regarding beliefs about capabilities, which was self-efficacy with BCT use for PA promotion.

- a.

- Limited self-efficacy: Physical therapists did not feel confident in their ability to successfully utilize BCTs to motivate patients to be more active. In general, they felt they were unsuccessful in their attempts to do this in practice.

- (v)

- Beliefs about consequences: Two themes mapped onto beliefs about consequences including (i) beliefs about how patient motivations, expectations, and emotions could impact the results of PA promotion and (ii) beliefs about how the patient environment (physical, social, and caregiver) could impact the results of PA promotion. There was a belief that barriers in these two domains would have negative consequences on efforts for PA promotion.

- a.

- Belief that patient motivations, expectations, and emotions impact the results of PA promotion: Most (n = 4) physical therapists felt that patients who were not motivated were “challenging”, and it was very difficult or not possible to change a patient’s exercise behaviors. Therapists also mentioned that when patients have unrealistic expectations for recovery, this can hinder the ability to promote activities that are achievable.

- b.

- Belief that the patient environment (physical, social, and caregiver) could impact the results of PA promotion: All therapists noted that logistical and environmental barriers make it challenging to encourage exercise. Cost, geographic location, transportation, and time impacts access to activity programming. Inconsistency and limited availability of PCAs is also a consideration as many community activity centers, such as gyms and adaptive programs, require a person to assist with transfers. These cumulative logistical barriers contribute to the challenge of promoting PA in this population.

- (vi)

- Goals/Intentions: One theme of goals and intentions was identified, which was therapist activity prescription priorities.

- a.

- Activity prescription priorities impact type of PA promoted: The goal of activity prescription was variable across participants. Some participants (n = 3) reported the goal for PA after discharge was to promote a home exercise program while others (n = 2) felt it was more important to emphasize community integration. One therapist felt it was important to provide clear activity guidelines, while the remainder encouraged patients just to be active in some capacity.

- (vii)

- Environmental context and resources: The themes of reimbursement structures and resources and time mapped onto this domain.

- a.

- Limitations due to reimbursement structures: Most of the therapists had the impression that using treatment time for PA and wellness-based treatments was non-billable or non-skilled (n = 4). Therapists felt that insurance coverage dictates why this is not performed in practice.

- b.

- Limitations due to resources and time: Most therapists (n = 4) reported that limited time was a barrier, both in finding time amongst many competing priorities for this complex patient population and the amount of time it takes to have difficult conversations surrounding motivation. Additionally, the availability of programs and skilled trainers to refer patients to also impacts the ability to promote PA to patients. Even in a large hospital-based clinic, the majority of therapists (n = 4) reported that finding resources that are accessible, affordable, and have the proper specialized equipment and care can be challenging to come by. Conversely, one therapist reported that within her hospital network, she felt lucky there were resources available to her patients.

- (viii)

- Social influences: Two themes mapped onto social influences, (i) healthcare team dynamics and (ii) patient/therapist dynamics.

- a.

- Healthcare team dynamics can facilitate PA promotion: Therapists felt that healthcare team dynamics including the referring physician or physiatrist support make a big difference in the effectiveness of PA promotion. Therapists report that consistent messaging across the healthcare team on the importance of PA, meeting PA guidelines, and support in promoting activity outside of PT was a facilitator to PA promotion.

- b.

- The patient/therapist dynamic impacts PA promotion: Therapists also reported that the dynamic between the patient and the therapist was important. When there was a good rapport and aligned expectations on activity, PA promotion was easier to perform, expressed by PT5. However, misaligned expectations can make it challenging.

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PA | Physical Activity |

| PT | Physical Therapist |

| BCT | Behavior Change Technique |

| SRQR | Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research |

| TDF | Theoretical Domains Framework |

| COM-B | Capability, Opportunity, and Motivation for Behavior Model |

| NCS | Board-Certified in Neurologic Physical Therapy |

| MS | Multiple Sclerosis |

| PD | Parkinson’s Disease |

| SCI | Spinal Cord Injury |

| AD | Assistive Device |

| PCA | Personal Care Assistant |

Appendix A

Appendix B. Interview Guide and Script

- ▪

- Have you ever heard of behavior change strategies?

- ▪

- Have you ever tried any strategies to promote carryover and behavior change (if they have heard of it, can also frame as motivation) in your practice? (For example, action planning, goal setting, etc.)

- What do you do? Why or why not? Follow up based on responses here

- ▪

- What is your sense of carryover based on the conversations you have? Do you track it?

- ▪

- What do you think are biggest limitations to your patients doing PA after discharge?

- ▪

- Do you feel that PT has a role in addressing any of these limitations?

- ▪

- Do you think that using these techniques would have any impact on PA?

- ▪

- I saw you used XX strategy/approach, what made you choose this approach? What made you choose XX approach with this patient specifically?

- ▪

- How do you choose with patients if you will do this?

- ▪

- Have you done any other approaches? If so, what?

- ▪

- What other factors do you weigh?

- ▪

- How often do you incorporate behavior change techniques into your practice? When do you typically start doing them within your plan of care?

- ▪

- Where did you learn about behavior change techniques? (additional training, cont ed, etc.?)

- ▪

- How do you feel about using these techniques?

- ▪

- How do you feel about others using these techniques?

- ▪

- Is there anything that would make doing this more often easier? Harder?

- Do you document these techniques? Do you bill for them?

- ▪

- What are your thoughts on the impact of using behavior change techniques in practice?promotion of physical activity

- What are your priorities for this patient to take away at discharge after your plan of care?

- I saw that you talked about (certain aspects of physical activity) with patient XX, what made you decide to bring this up?

- ○

- Did you plan on having this conversation going into the session?

- How do you think your patient responded to the conversation?

- ○

- Have you talked to this patient about PA before?

- ○

- Do you think XX will continue a PA plan after discharge? Why or why not?

- ○

- What do you think your role is in XX activity level post d/c?

- ○

- How do you typically approach physical activity conversations throughout the plan of care?

- ○

- Do you plan on doing any follow up on this conversation?

- ○

- Do you assess barriers/facilitators to physical activity in the home and community during your plan of care?

- ○

- What is the typical response you get from your patients when you bring PA up?

- I saw that you chose to talk to XX about PA but not YY, can you talk to me about why?

- ○

- What do you think makes some patients better candidates for PA outside of the clinic?

- ○

- What factors do you consider when you promote PA?

- What do you think the PT role is in promoting physical activity after discharge in xx population?

- What resources do you rely on to help promote PA?

- ○

- What resources do you wish you had?

- ○

- Do you think insurance provides sufficient resources and reimbursement to support this part of your treatment?

- Do you ever use any guidelines for physical activity conversations and exercise? How did you learn about any guidelines?

- How do you track/measure PA that happens outside of the clinic?

- Did you talk about any activity plans in this patient’s discharge? If so, what?

- ▪

- Are there any diagnoses that you are more or less likely to emphasize PA with? How about specific subpopulations (ie chronic or subacute?)

- ▪

- Are there any health conditions that make you less likely to promote PA?

- ▪

- Are there any environmental factors you consider?

- ▪

- Any personal factors?

- What specific barriers/facilitators to PA does this patient have in your opinion?

- ○

- If no, what other types of exercises and activities do you typically put into a home program at discharge?

- ○

- Is physical activity included? Why or why not?

- What are the barriers you see to your patients staying active after d/c?

- ○

- Is there anything that you think PTs can address?

- ○

- Is there anything that you think would help PTs be able to better address this barrier (resources, environmental changes, etc.)?

- What do you think PT role in health promotion is?

Appendix C

References

- Global, regional, and national burden of neurological disorders, 1990–2016: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Neurol. 2019, 18, 459–480. [CrossRef]

- Kalb, R.; Brown, T.R.; Coote, S.; Costello, K.; Dalgas, U.; Garmon, E.; Giesser, B.; Halper, J.; Karpatkin, H.; Keller, J.; et al. Exercise and lifestyle physical activity recommendations for people with multiple sclerosis throughout the disease course. Mult. Scler. J. 2020, 26, 1459–1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginis, K.A.M.; van der Scheer, J.W.; Latimer-Cheung, A.E.; Barrow, A.; Bourne, C.; Carruthers, P.; Bernardi, M.; Ditor, D.S.; Gaudet, S.; de Groot, S.; et al. Evidence-based scientific exercise guidelines for adults with spinal cord injury: An update and a new guideline. Spinal Cord 2018, 56, 308–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billinger, S.A.; Arena, R.; Bernhardt, J.; Eng, J.J.; Franklin, B.A.; Johnson, C.M.; MacKay-Lyons, M.; Macko, R.F.; Mead, G.E.; Roth, E.J.; et al. Physical Activity and Exercise Recommendations for Stroke Survivors. Stroke 2014, 45, 2532–2553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleindorfer, D.O.; Towfighi, A.; Chaturvedi, S.; Cockroft, K.M.; Gutierrez, J.; Lombardi-Hill, D.; Kamel, H.; Kernan, W.N.; Kittner, S.J.; Leira, E.C.; et al. 2021 Guideline for the Prevention of Stroke in Patients with Stroke and Transient Ischemic Attack: A Guideline From the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke 2021, 52, e364–e467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, N.F.; Gulanick, M.; Costa, F.; Fletcher, G.; Franklin, B.A.; Roth, E.J.; Shephard, T. Physical Activity and Exercise Recommendations for Stroke Survivors. Circulation 2004, 109, 2031–2041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhalsing, K.S.; Abbas, M.M.; Tan, L.C.S. Role of Physical Activity in Parkinson’s Disease. Ann. Indian Acad. Neurol. 2018, 21, 242–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalgas, U.; Stenager, E. Exercise and disease progression in multiple sclerosis: Can exercise slow down the progression of multiple sclerosis? Ther. Adv. Neurol. Disord. 2012, 5, 81–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quinn, L.; Morgan, D. From Disease To Health: Physical Therapy Health Promotion Practices for Secondary Prevention in Adult and Pediatric Neurologic Populations. J. Neurol. Phys. Ther. 2017, 41 (Suppl. S3), S46–S54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- English, C.; Healy, G.N.; Coates, A.; Lewis, L.; Olds, T.; Bernhardt, J. Sitting and Activity Time in People with Stroke. Phys. Ther. 2016, 96, 193–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danoudis, M.; Iansek, R. Physical activity levels in people with Parkinson’s disease treated by subthalamic nucleus deep brain stimulation. Disabil. Rehabil. 2023, 45, 2890–2895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casey, B.; Coote, S.; Galvin, R.; Donnelly, A. Objective physical activity levels in people with multiple sclerosis: Meta-analysis. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2018, 28, 1960–1969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soriano, J.E.; Squair, J.W.; Cragg, J.J.; Thompson, J.; Sanguinetti, R.; Vaseghi, B.; Emery, C.A.; Grant, C.; Charbonneau, R.; Larkin-Kaiser, K.A.; et al. A national survey of physical activity after spinal cord injury. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 4405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Global Action Plan on Physical Activity 2018–2030: More Active People for a Healthier World: At-A-Glance. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-NMH-PND-18.5 (accessed on 28 June 2025).

- Petrella, R.J.; Lattanzio, C.N. Does counseling help patients get active? Systematic review of the literature. Can. Fam. Physician 2002, 48, 72–80. [Google Scholar]

- Sharp, P.; Spence, J.C.; Bottorff, J.L.; Oliffe, J.L.; Hunt, K.; Vis-Dunbar, M.; Caperchione, C.M. One small step for man, one giant leap for men’s health: A meta-analysis of behaviour change interventions to increase men’s physical activity. Br. J. Sports Med. 2020, 54, 1208–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, N.F.; Harding, K.E.; Dennett, A.M.; Febrey, S.; Warmoth, K.; Hall, A.J.; Prendergast, L.A.; Goodwin, V.A. Behaviour change interventions to increase physical activity in hospitalised patients: A systematic review, meta-analysis and meta-regression. Age Ageing 2022, 51, afab154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motl, R.W.; Lein, D.H.; Morris, D.M.; Lowman, J.D.; Perez, P.; Bullard, C. Behavior Change Interventions for Health Promotion in Physical Therapist Research and Practice: An Integrative Approach. Phys. Ther. 2022, 102, pzab266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo-Soares, V.; Hankonen, N.; Presseau, J.; Rodrigues, A.; Sniehotta, F.F. Developing Behavior Change Interventions for Self-Management in Chronic Illness. Eur. Psychol. 2019, 24, 7–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beinart, N.A.; Goodchild, C.E.; Weinman, J.A.; Ayis, S.; Godfrey, E.L. Individual and intervention-related factors associated with adherence to home exercise in chronic low back pain: A systematic review. Spine J. 2013, 13, 1940–1950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eisele, A.; Schagg, D.; Krämer, L.V.; Bengel, J.; Göhner, W. Behaviour change techniques applied in interventions to enhance physical activity adherence in patients with chronic musculoskeletal conditions: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Patient Educ. Couns. 2019, 102, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kringle, E.A.; Gibbs, B.B.; Campbell, G.; McCue, M.; Terhorst, L.; Kersey, J.; Skidmore, E.R. Influence of Interventions on Daily Physical Activity and Sedentary Behavior after Stroke: A Systematic Review. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2020, 12, 186–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.; Xu, D.; Yang, M.; Ma, X.; Yan, N.; Chen, H.; He, S.; Deng, N. Behaviour change techniques that constitute effective planning interventions to improve physical activity and diet behaviour for people with chronic conditions: A systematic review. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e058229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Martín, J.; Roldán-Jiménez, C.; De-Torres, I.; Muro-Culebras, A.; Escriche-Escuder, A.; Gonzalez-Sanchez, M.; Ruiz-Muñoz, M.; Mayoral-Cleries, F.; Biró, A.; Tang, W.; et al. Behavior Change Techniques and the Effects Associated With Digital Behavior Change Interventions in Sedentary Behavior in the Clinical Population: A Systematic Review. Front. Digit. Health 2021, 3, 620383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, K.; Davey, R.; Keegan, R.; Kunstler, B.; Woodward, A.; Freene, N. Behaviour change techniques in cardiovascular disease smartphone apps to improve physical activity and sedentary behaviour: Systematic review and meta-regression. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2022, 19, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keyworth, C.; Epton, T.; Goldthorpe, J.; Calam, R.; Armitage, C.J. Are healthcare professionals delivering opportunistic behaviour change interventions? A multi-professional survey of engagement with public health policy. Implement. Sci. 2018, 13, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albert, F.A.; Crowe, M.J.; Malau-Aduli, A.E.O.; Malau-Aduli, B.S. Physical Activity Promotion: A Systematic Review of The Perceptions of Healthcare Professionals. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carmeli, E. Physical Therapy for Neurological Conditions in Geriatric Populations. Front. Public Health 2017, 5, 333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frese, E.M.; Fick, A.; Sadowsky, H.S. Blood Pressure Measurement Guidelines for Physical Therapists. Cardiopulm. Phys. Ther. J. 2011, 22, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhagen, E.; Engbers, L. The physical therapist’s role in physical activity promotion. Br. J. Sports Med. 2009, 43, 99–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spellman, C.; Craike, M.; Livingston, P. Knowledge, attitudes and practices of clinicians in promoting physical activity to prostate cancer survivors. Health Educ. J. 2014, 73, 566–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lein, D.H.; Clark, D.; Graham, C.; Perez, P.; Morris, D. A Model to Integrate Health Promotion and Wellness in Physical Therapist Practice: Development and Validation. Phys. Ther. 2017, 97, 1169–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buscemi, V.; Boaz, A.; Dawes, H.; Jaki, T.; Jones, F.; Lowe, R.; Marsden, J.; Paul, L.; Playle, R.; Randell, E.; et al. Physical activity and exercise interventions for people with rare neurological disorders: A scoping review of systematic reviews. Res. Sq. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulligan, H.F.; Hale, L.A.; Whitehead, L.; Baxter, G.D. Barriers to physical activity for people with long-term neurological conditions: A review study. Adapt. Phys. Act. Q. 2012, 29, 243–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newitt, R.; Barnett, F.; Crowe, M. Understanding factors that influence participation in physical activity among people with a neuromusculoskeletal condition: A review of qualitative studies. Disabil. Rehabil. 2016, 38, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rimmer, J.H.; Riley, B.; Wang, E.; Rauworth, A.; Jurkowski, J. Physical activity participation among persons with disabilities: Barriers and facilitators. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2004, 26, 419–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, B.C.; Harris, I.B.; Beckman, T.J.; Reed, D.A.; Cook, D.A. Standards for reporting qualitative research: A synthesis of recommendations. Acad. Med. 2014, 89, 1245–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunniss, S.; Kelly, D.R. Research paradigms in medical education research. Med. Educ. 2010, 44, 358–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- William, F.K.A. Interpretivism or Constructivism: Navigating Research Paradigms in Social Science Research. Interpret. Or Constr. Navig. Res. Paradig. Soc. Sci. Res. 2024, 143, 134–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxwell, J.A. Qualitative Research Design: An Interactive Approach, 2nd ed.; Sage Publications: Singapore, 2005; Volume 41, Available online: https://www.sagepublications.com (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Michie, S.; van Stralen, M.M.; West, R. The behaviour change wheel: A new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implement. Sci. 2011, 6, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cane, J.; O’Connor, D.; Michie, S. Validation of the theoretical domains framework for use in behaviour change and implementation research. Implement. Sci. 2012, 7, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- COM-B + TDF. The Center for Implementation. Available online: https://thecenterforimplementation.com/toolbox/com-b-tdf (accessed on 7 July 2025).

- McGowan, L.J.; Powell, R.; French, D.P. How can use of the Theoretical Domains Framework be optimized in qualitative research? A rapid systematic review. Br. J. Health Psychol. 2020, 25, 677–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkins, L.; Francis, J.; Islam, R.; O’cOnnor, D.; Patey, A.; Ivers, N.; Foy, R.; Duncan, E.M.; Colquhoun, H.; Grimshaw, J.M.; et al. A guide to using the Theoretical Domains Framework of behaviour change to investigate implementation problems. Implement. Sci. 2017, 12, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, C.S.; Mendes, R.; Godinho, C.; Monteiro-Pereira, A.; Pimenta-Ribeiro, J.; Martins, H.S.; Brito, J.; Themudo-Barata, J.L.; Fontes-Ribeiro, C.; Teixeira, P.J.; et al. Predictors of physical activity promotion in clinical practice: A cross-sectional study among medical doctors. BMC Med. Educ. 2022, 22, 624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGrath, A.; Lambe, B.; Matthews, E.; McDonnell, K.; Harrison, M.; Kehoe, B. Determinants of physical activity promotion in primary care from the patient perspective of people at risk of or living with chronic disease: A COM-B analysis. BMC Prim. Care 2024, 25, 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michie, S.; Richardson, M.; Johnston, M.; Abraham, C.; Francis, J.; Hardeman, W.; Eccles, M.P.; Cane, J.; Wood, C.E. The behavior change technique taxonomy (v1) of 93 hierarchically clustered techniques: Building an international consensus for the reporting of behavior change interventions. Ann. Behav. Med. 2013, 46, 81–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connell, L.E.; Carey, R.N.; de Bruin, M.; Rothman, A.J.; Johnston, M.; Kelly, M.P.; Michie, S. Links Between Behavior Change Techniques and Mechanisms of Action: An Expert Consensus Study. Ann. Behav. Med. 2019, 53, 708–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willmott, T.J.; Pang, B.; Rundle-Thiele, S. Capability, opportunity, and motivation: An across contexts empirical examination of the COM-B model. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conger, S.A.; Herrmann, S.D.; Willis, E.A.; Nightingale, T.E.; Sherman, J.R.; Ainsworth, B.E. 2024 Wheelchair Compendium of Physical Activities: An update of activity codes and energy expenditure values. J. Sport Health Sci. 2024, 13, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willis, E.A.; Herrmann, S.D.; Hastert, M.; Kracht, C.L.; Barreira, T.V.; Schuna, J.M.; Cai, Z.; Quan, M.; Conger, S.A.; Brown, W.J.; et al. Older Adult Compendium of Physical Activities: Energy costs of human activities in adults aged 60 and older. J. Sport Health Sci. 2024, 13, 13–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fife, S.T.; Gossner, J.D. Deductive Qualitative Analysis: Evaluating, Expanding, and Refining Theory. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2024, 23, 16094069241244856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, V.; Braun, V. Teaching thematic analysis: Overcoming challenges and developing strategies for effective learning. Psychol. 2013, 26, 120–123. [Google Scholar]

- Naeem, M.; Ozuem, W.; Howell, K.; Ranfagni, S. A Step-by-Step Process of Thematic Analysis to Develop a Conceptual Model in Qualitative Research. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2023, 22, 16094069231205789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shenton, A.K. Strategies for ensuring trustworthiness in qualitative research projects. Educ. Inf. 2004, 22, 63–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowman, T.; Mattos, F.G.M.; Salvalaggio, S.; Marazzini, F.; Longo, C.A.; Bocini, S.; Gennuso, M.; Materazzi, F.G.; Pelosin, E.; Putzolu, M.; et al. Classification and Quantification of Physical Therapy Interventions across Multiple Neurological Disorders: An Italian Multicenter Network. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 6483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barton, C.; King, M.; Dascombe, B.; Taylor, N.; Silva, D.d.O.; Holden, S.; Goff, A.; Takarangi, K.; Shields, N. Many physiotherapists lack preparedness to prescribe physical activity and exercise to people with musculoskeletal pain: A multi-national survey. Phys. Ther. Sport 2021, 49, 98–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heron, N.; Kee, F.; Donnelly, M.; Cardwell, C.; Tully, M.A.; Cupples, M.E. Behaviour change techniques in home-based cardiac rehabilitation: A systematic review. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 2016, 66, e747–e757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rethorn, Z.D.; Covington, J.K.; Cook, C.E.; Bezner, J.R. Physical Activity Promotion: Moving From Talking the Talk to Walking the Walk. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 2022, 52, 236–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bridging the Gap. Available online: https://neuropt.org/practice-resources/health-promotion-and-wellness/clinician-resources---tools/bridging-the-gap (accessed on 6 July 2025).

- Kennedy, W.; Curtin, C.; Bowling, A. Access to physical activity promotion for people with neurological conditions: Are physical therapists leading the way? Disabil. Health J. 2024, 17, 101517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, S.A.; Hrisos, N.; Flynn, D.; Errington, L.; Price, C.; Avery, L. How should long-term free-living physical activity be targeted after stroke? A systematic review and narrative synthesis. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2018, 15, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moniz, A.; Duarte, S.T.; Aguiar, P.; Caeiro, C.; Pires, D.; Fernandes, R.; Moço, D.; Marques, M.M.; Sousa, R.; Canhão, H.; et al. Physiotherapists’ barriers and facilitators to the implementation of a behaviour change-informed exercise intervention to promote the adoption of regular exercise practice in patients at risk of recurrence of low back pain: A qualitative study. BMC Prim. Care 2024, 25, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulligan, H.; Fjellman-Wiklund, A.; Hale, L.; Thomas, D.; Häger-Ross, C. Promoting physical activity for people with neurological disability: Perspectives and experiences of physiotherapists. Physiother. Theory Pract. 2011, 27, 399–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, T.L.; Smith, B.; Papathomas, A. Physical activity promotion for people with spinal cord injury: Physiotherapists’ beliefs and actions. Disabil. Rehabil. 2018, 40, 52–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- APTA. Skilled Maintenance Therapy Under Medicare. Available online: https://www.apta.org/your-practice/payment/medicare-payment/coverage-issues/skilled-maintenance-therapy-under-medicare (accessed on 24 June 2025).

- APTA. PTs’ Role in Prevention Wellness Health Promotion. Available online: https://www.apta.org/apta-and-you/leadership-and-governance/policies/pt-role-advocacy (accessed on 29 July 2025).

- Dean, E.; de Andrade, A.D.; O’Donoghue, G.; Skinner, M.; Umereh, G.; Beenen, P.; Cleaver, S.; Afzalzada, D.; Delaune, M.F.; Footer, C.; et al. The Second Physical Therapy Summit on Global Health: Developing an action plan to promote health in daily practice and reduce the burden of non-communicable diseases. Physiother. Theory Pract. 2014, 30, 261–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaMarca, A.; Karim, R.; Larsen, G.; Tse, I.; Wechsler, S.; Gauthier, L.V.; Keysor, J. Behaviorally Informed Interventions to Promote Activity in the Home and Community for Adults with Neurological Disorders: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Phys. Ther. 2025, pzaf117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gauthier, L.V.; Rider, J.V.; Donkers, S. Applying Behavior Change Techniques to Support Client Outcomes in Outpatient Neurorehabilitation: A Clinician Guide. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2023, 104, 711–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donkers, S.J.; Chan, K.; Milosavljevic, S.; Pakosh, M.; Musselman, K.E. Informing the training of health care professionals to implement behavior change strategies for physical activity promotion in neurorehabilitation: A systematic review. Transl. Behav. Med. 2020, 10, 310–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Therapist | Gender | Age (Years) | Specialty Certifications | Years of Experience |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PT 1 | F | 34 | NCS | 5 |

| PT 2 | F | 41 | NCS | 15 |

| PT 3 | F | 29 | 4 | |

| PT 4 | M | 32 | NCS | 7 |

| PT 5 | F | 54 | 34 |

| Patient | Therapist | Gender | Age (Years) | Diagnosis | Ambulation Status | Caregiver in Session |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| O1 | PT1 | M | 66 | SCI | Primarily w/c user | Yes |

| O2 | PT2 | F | 62 | Stroke | Walks with AD | No |

| O3 | PT4 | F | 72 | Stroke | Walks with AD | Yes |

| O4 | PT4 | F | 32 | SCI | Primarily w/c user | No |

| O5 | PT3 | M | 81 | PD | Primarily w/c user | Yes |

| O6 | PT3 | F | 49 | MS | Walks with AD | No |

| O7 | PT1 | M | 59 | Stroke | Walks without AD | Yes |

| O8 | PT2 | M | 68 | PD | Walks without AD | No |

| O9 | PT5 | M | 62 | Stroke | Walks with AD | No |

| O10 | PT5 | M | 54 | Stroke | Walks without AD | Yes |

| BCT | Example from Field Note |

|---|---|

| Instructions on how to perform the behavior | The physical therapist brings up the documents she gave to them and repeats the instructions again for the exercise. “See how [the] walker is starting to move out, here is how you bring the walker back towards you”—(PT1, O1) |

| Behavioral practice and rehearsal | The therapist says, “let’s practice some [exercises] that I think would be good for you.”—(PT4, O3) |

| Social support | He encourages her to return to the rowing program—(PT4, O4) |

| Credible source | “I have a question for you though, which exercise is the one I’m the weakest at? What should I work on [at home]?” The therapist says “the balance”—(PT5, O10) |

| Adding objects to the environment | “You see brace clinic next week. When you get the brace, you will use it at home and it will help”—(PT3, O6) |

| Goal setting | The therapist asks “Do you have any new goals that we should work on?” and the patient reports he wants to play a round of golf—(PT2, O8) |

| Therapist Reported Strategy | BCT Used in Observation |

|---|---|

| Education (5/5) | “Instruction on how to perform the behavior” (10/10) “Credible source” (6/10) |

| Building Social support/relationships (4/5) | “Social support” (9/10) |

| Goals and planning (4/5) | “Goal setting” (5/10) |

| Personalization (5/5) | No associated BCT code |

| Behavior substitution (1/5) | “Behavioral substitution” (1/10) |

| Adding visual cues for exercise (1/5) | “Prompts and cues” (3/10) |

| Not in interview | “Behavioral practice and rehearsal” (9/10) |

| Not in interview | “Adding objects to the environment” (6/10) |

| TDF Domain | Theme | Example(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Knowledge | Lack of awareness of community resources/referrals | “I would like more geographical information or [a] flyer or handout for us to access. You know, new up-and-coming established programs. Because I think a lot of it is hearsay. There’s an email thrown out like here or there” (PT2) “I often just tell people like, ‘Go find a personal trainer’ [but] I don’t have names.” (PT4) |

| Limited knowledge of PA prescription and BCT applications | “Do you know any resources as far as exercise, prescription recommendations for the neuro population that are good? The American Heart Association [has] recommendations for exercise, but those are so out of reach, for most of my people.” (PT4) “Behavior change… I remember doing a health promotion project during PT School, where I looked at a specific model, and I can’t [remember]. I’m sure it probably influences some of what I do but could I tell you what it is?” (PT1) | |

| Memory, attention, and decision processes | Clinical decision-making impacts how PA is promoted | “I have identified a cognitive impairment, [so] I didn’t want to give him anything super hard to follow… So, the exercises I gave him [are] really basic…I just kind of thought about what would be easy enough for him to do…. or another patient, she has MS and her balance is pretty inconsistent. I want to give her something that’s not going to fatigue her too much. So that’s been kind of something I’ve kept in the back of my mind” (PT3) “I think the fear is from a patient perspective, the fear will always be that this is the last leg of rehab [ilitation] outpatient, and then I’m discharging you. ‘Oh, my goodness, am I going to be just left, hanging… like I don’t know what to do.’…. And so, releasing that hand a little slowly, would be a good idea if they are acute patients and if they’re chronic, of course they already know [what to do]. So I think that is also important to understand that in our patients [this] is the last leg of their rehab journey for the acute patients. And the discharge plan, you already think of where are they going to continue [activity]’”(PT5) |

| Professional Role | Physical therapy has a limited role in health promotion and wellness | “Because then I’ve discharged them. It’s not something that they are on my program for me to follow up in the gym. Then that’s left to the gym instructors. That’s a different role” (PT5) |

| PT role is for education, not motivation for community activity and participation | “I think we should view the continuity of care not ending an outpatient. I think it needs to be about what’s then the plan for people being integrated in communities. And it’s not just ‘are they meeting the physical activity guidelines?’ Yes, they should. But are they able to participate in society? Are they able to work? Are they able to go to a restaurant? Are they able to go to a gym?” (PT1) “[I am] providing and educating on examples of opportunities that they can take part of, but we talk about ultimately there’s only so much I can do, It’s kind of on them. And I try to make that expectation of them doing their part.” (PT2) | |

| Belief about capabilities | Limited self-efficacy | “I don’t know if I’m good at it, to be honest. I feel like I should take some community courses on it. It’s actually on my list of things to improve on cause yeah, I work hard at doing a day of motivational interviewing with people and trying to have them figure out how to make themselves better. …But I don’t know if I’ve been successful at it.” (PT4) |

| Belief about consequences | Belief that patient motivations, expectations, and emotions impact the results of PA promotion | “People are the same people they were before the injury or after the injury, like if they weren’t motivated to exercise before they’re not motivated to exercise afterward” (PT3) “You know, those are the more challenging patients to get into a routine…. The expectations that some patients have who have neuro diagnoses are sometimes a little bit far-fetched.” (PT2) |

| Belief that the patient environment (physical, social, and caregiver) could impact the results of PA promotion | “It’s a production… [it] takes all day for them to do any activity. So for them to go to the gym [or] to meet a personal trainer for half an hour… Yes, they were doing that for me but that is a healthcare thing. But when it’s not, and now they’re paying for the ride, they’re paying for the personal trainer, they’re spending half the day doing it, and [they’re paying for] their PCA… so it becomes a whole ordeal where it takes them a whole day to go to the gym. So then they don’t…. so this is probably my biggest challenge, my biggest barrier” (PT4) | |

| Goals/intentions | Activity prescription priorities impact type of PA promoted | “My goal would be to have them have like a routine and exercise program for them to continue on outside of this space.” (PT2) ‘I definitely am less focused on the exercise as a prescription and more focused on the exercise as a tool for activity and like to do life.” (PT4) |

| Environmental context and resources | Limitations due to reimbursement Structures | “I always have always been a huge advocate for creating [activity] programs. Unfortunately, now, it’s so insurance [and] productivity driven that we cannot bill these patients.” (PT5) |

| Limitations due to resources and time | “But having those conversations was quite challenging. And so I spent a lot of effort doing it…it’s a time thing. it is the setting aside the time to have the difficult conversation” (PT4) “For people who need specialized equipment, I would love to be able to send everyone to an affordable, geographically accessible, adaptive gym, where there’s a standing frame that you can use…. I think, just like in the able bodied, or non-disabled population, it’s a question of access, ease, geographic access, money. It’s going to be the same in this population. But there’s less options [to refer to].” (PT1) “I don’t know about everyone else, I can only say for myself, my patients have the resources. I mean, I hope everyone does. We’re lucky we’re here…. At [our hospital], we have the adaptive sports program…we have a lot of groups, there’s support groups here.” (PT5) | |

| Social influences | Healthcare team dynamics | “I think I’m also lucky, like one of the physiatrists… He also often makes that [physical activity] a recommendation too. So, I think we both see each other’s notes, and we’re like, “Oh, Hey, cool!” And it’s nice having people on the same page.” (PT1) |

| Patient/therapist dynamic | “So you’re interacting with them a lot. So you build up that rapport where you know this motivates them [or] that doesn’t motivate them. …. So you know, coming to therapy motivates them [to be active].” (PT5) “She had a massive aneurysm, and she always wants to walk every single time she’s here, but couldn’t really walk… the whole PT Episode, she perseverates on wanting to walk but she can’t. So we never actually get anything done because walking, was never really a reasonable goal for her…. and the discharge for her has always been really emotional for her and her mom, and everybody’s really upset” (PT4) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

LaMarca, A.; Larsen, G.; Lyons, K.D.; Keysor, J. Physical Therapists’ Use of Behavior Change Strategies to Promote Physical Activity for Individuals with Neurological Conditions. Healthcare 2025, 13, 2485. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13192485

LaMarca A, Larsen G, Lyons KD, Keysor J. Physical Therapists’ Use of Behavior Change Strategies to Promote Physical Activity for Individuals with Neurological Conditions. Healthcare. 2025; 13(19):2485. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13192485

Chicago/Turabian StyleLaMarca, Amber, Gwendolyn Larsen, Kathleen D. Lyons, and Julie Keysor. 2025. "Physical Therapists’ Use of Behavior Change Strategies to Promote Physical Activity for Individuals with Neurological Conditions" Healthcare 13, no. 19: 2485. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13192485

APA StyleLaMarca, A., Larsen, G., Lyons, K. D., & Keysor, J. (2025). Physical Therapists’ Use of Behavior Change Strategies to Promote Physical Activity for Individuals with Neurological Conditions. Healthcare, 13(19), 2485. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13192485