Effect of the Primary Nursing Model on Self-Care Skills of Hospitalized Older Patients with Multimorbidity: A Quasi-Experimental Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design and Participants

2.2. Intervention

Objectives and Hypotheses

- Specific objectives:

- Hypotheses:

2.3. Measures

2.4. Data Collection

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Validation of the Psychometric Properties of the Therapeutic Self-Care Scale—Portuguese Version for People with Multimorbidity in Hospital (EATPPMH)

- Factor 1—Recognizing and managing signs and symptoms (4 items): explained 60.7% (intervention) and 49.5% (control) of variance.

- Factor 2—Managing changes in health status (5 items): explained 13.7% (intervention) and 10.8% (control).

- Factor 3—Managing medication (3 items): explained 7.2% (intervention) and 12.3% (control).

3.2. Therapeutic Self-Care at Admission, Discharge, and Follow-Up

4. Discussion

Recommendations and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Paper Section/ Topic | Item No | Descriptor | Reported? | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| √ | Pg # | |||

| Title and Abstract | ||||

| Title and Abstract | 1 |

| x | 1 |

| x | 1 | ||

| x | 1 | ||

| Introduction | ||||

| Background | 2 |

| x | 2 |

| x | 2 | ||

| Methods | ||||

| Participants | 3 |

| x | 3 |

| x | 3 | ||

| x | 3 | ||

| x | 3 | ||

| Interventions | 4 |

| x | 3 |

| x | 3 | ||

| x | 3 | ||

| x | 3 | ||

| x | 3 | ||

| x | 3 | ||

| x | 3 | ||

| x | 4 | ||

| NA | |||

| Objectives | 5 |

| x | 4 |

| Outcomes | 6 |

| x | 4 |

| x | 4 | ||

| x | 4 | ||

| Sample Size | 7 |

| x | 3 |

| Assignment Method | 8 |

| x | 3 |

| x | 4–5 | ||

| x | 4–5 | ||

| Blinding (masking) | 9 |

| NA | |

| Unit of Analysis | 10 |

| x | 3 |

| NA | |||

| Statistical Methods | 11 |

| x | 4–5 |

| x | 4–5 | ||

| NA | |||

| x | 4–5 | ||

| Results | ||||

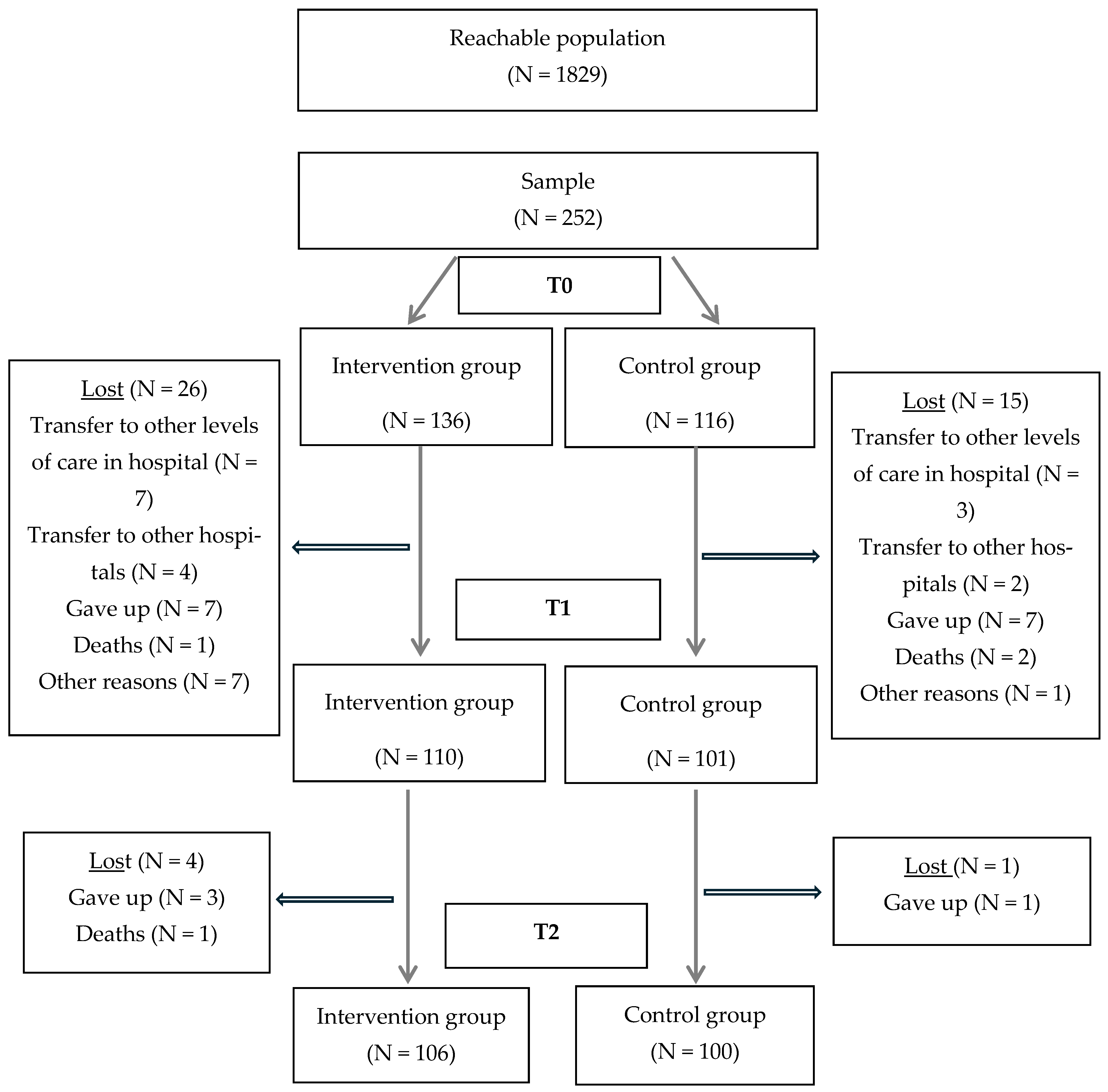

| Participant flow | 12 |

| x | 6 |

| x | 6 | ||

| x | 6 | ||

| x | 6 | ||

| x | 6 | ||

| x | 6 | ||

| NA | |||

| Recruitment | 13 |

| x | 3 |

| Baseline Data | 14 |

| x | 6–7 |

| NA | |||

| NA | |||

| x | 6–7 | ||

| Baseline equivalence | 15 |

| x | 7 |

| Numbers analyzed | 16 |

| x | 8–9 |

| NA | |||

| Outcomes and estimation | 17 |

| x | 8–9 |

| x | 8–9 | ||

| NA | |||

| Ancillary analyses | 18 |

| NA | |

| Adverse events | 19 |

| x | 8–9 |

| Discussion | ||||

| Interpretation | 20 |

| x | 9–10 |

| x | 9–10 | ||

| x | 9–10 | ||

| x | 10–11 | ||

| Generalizability | 21 |

| x | 10–11 |

| Overall Evidence | 22 |

| x | 10–11 |

References

- Moulton, J.E.; Withanage, N.N.; Subasinghe, A.K.; Mazza, D. Nurse-Led Service Delivery Models in Primary Care: A Scoping Review Protocol Nurse-Led Service Delivery Models in Primary Care: A Scoping Review Protocol. BJGP Open 2022, 6, BJGPO.2021.0194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mercer, S.; Salisbury, C.; Fortin, M. ABC of Multimorbidity; Wiley BMJ Books; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Gonçalves, M.I.R.; Mendes, D.A.; Caldeira, S.; Jesus, E.; Nunes, E. Nurse-Led Care Management Models for Patients with Multimorbidity in Hospital Settings: A Scoping Review. J. Nurs. Manag. 2022, 30, 1960–1973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffart, N.; Woods, C.Q. Elements of a Nursing Professional Practice Model. J. Prof. Nurs. 1996, 12, 354–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairbrother, G.; Chiarella, M.; Braithwaite, J. Models of Care Choices in Today’s Nursing Workplace: Where Does Team Nursing Sit? Aust. Health Rev. 2015, 39, 489–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fawcett, J. More Thoughts About Models of Nursing Practice Delivery. Nurs. Sci. Q. 2021, 34, 458–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fawcett, J. Thoughts About Models of Nursing Practice Delivery. Nurs. Sci. Q. 2021, 34, 328–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parreira, P.; Santos-Costa, P.; Neri, M.; Marques, A.; Queirós, P.; Salgueiro-Oliveira, A. Work Methods for Nursing Care Delivery. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manthey, M. The Practice of Primary Nursing, 2nd ed.; Creative Health Care Management, Inc.: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Manthey, M. Aka Primary Nursing. JONA J. Nurs. Adm. 2003, 33, 369–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doran, D.; Sidani, S.; Keatings, M.; Doidge, D. An Empirical Test of the Nursing Role Effectiveness Model. J. Adv. Nurs. 2002, 38, 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidani, S. Self-Care. In Nursing Outcomes: The State of the Science; Doran, D., Ed.; Jones & Bartlett Learning: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2011; pp. 79–130. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Ageing and Health. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ageing-and-health (accessed on 22 August 2023).

- Payne, R.; Steakley, B. Establishing a Primary Nursing Model of Care. Nurs. Manag. 2015, 46, 11–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, I.; Mendes, D.A.; Caldeira, S.; Jesus, É.; Nunes, E. The Primary Nursing Care Model and Inpatients’ Nursing-Sensitive Outcomes: A Systematic Review and Narrative Synthesis of Quantitative Studies. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 2391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, Å.; Frank, C.; Willman, A.M.L.; Sandman, P.O.; Hansebo, G. Factors Contributing to Serious Adverse Events in Nursing Homes. J. Clin. Nurs. 2018, 27, e354–e362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, M.; Collins, R.; Drennan, J.; Halligan, P.; O’Mathúna, D.P.; Schultz, T.J.; Sheridan, A.; Vilis, E. Hospital Nurse Staffing Models and Patient and Staff-Related Outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Des Jarlais, D.C.; Lyles, C.; Crepaz, N. Improving the Reporting Quality of Nonrandomized Evaluations of Behavioral and Public Health Interventions: The TREND Statement. Am. J. Public Health 2004, 94, 361–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dal Molin, A.; Gatta, C.; Boggio Gilot, C.; Ferrua, R.; Cena, T.; Manthey, M.; Croso, A. The Impact of Primary Nursing Care Pattern: Results from a before–After Study. J. Clin. Nurs. 2018, 27, 1094–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cardoso, A.F.; Queiros, P.; Ribeiro, C.F.; Amaral, A. Cultural Adaptation and Psychometric Properties of the Portuguese Version of the Therapeutic Self-Care Scale. Int. J. Caring Sci. 2014, 7, 426–436. [Google Scholar]

- Marôco, J. Análise Estatística Com o SPSS Statistics, 7th ed.; ReportNumber, Lda.: Pero Pinheiro, Portugal, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L.; Ma, L.; Sun, F.; Tang, Z.; Chan, P. A Multicenter Study of Multimorbidity in Older Adult Inpatients in China. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2020, 24, 269–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, S.E.; Aaby, A.; Friis, K.; Maindal, H.T. Multimorbidity and Health Literacy: A Population-Based Survey among 28,627 Danish Adults. Scand. J. Public Health 2023, 51, 165–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, A.C.P.; Maximiano-Barreto, M.A.; Martins, T.C.R.; Luchesi, B.M. Factors Associated with Poor Health Literacy in Older Adults: A Systematic Review. Geriatr. Nurs. 2024, 55, 242–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belachew, A.; Cherbuin, N.; Bagheri, N.; Burns, R. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of the Socioeconomic, Lifestyle, and Environmental Factors Associated with Healthy Ageing in Low and Lower-Middle-Income Countries. J. Popul. Ageing 2024, 17, 365–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faessler, L.; Kofler, S.; Wenke-Zobler, J.; Brunner, C.; Schäfer-Keller, P.; De Geest, S.; Schubert, M.; Regez, K.; Schuetz, P.; Mueller, B.; et al. The Use of Nurse-Led Care Intervention to Improve Self-Care Abilities Subsequently Decreasing Readmission in Multimorbid Hospitalized Patients: A Quasi-Experimental Study in a Real-World Setting. Nurs. Open 2023, 6, 3787–3798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, R.; Geng, J.; Liu, J.; Wang, G.; Hesketh, T. Effectiveness of Integrating Primary Healthcare in Aftercare for Older Patients after Discharge from Tertiary Hospitals—A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Age Ageing 2022, 51, afac151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomlinson, J.; Cheong, V.L.; Fylan, B.; Silcock, J.; Smith, H.; Karban, K.; Blenkinsopp, A. Successful Care Transitions for Older People: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of the Effects of Interventions That Support Medication Continuity. Age Ageing 2020, 49, 558–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Hospital & Healthcare Federation. Using Evidence in Healthcare Management; European Hospital & Healthcare Federation: Brussels, Belgium, 2022; Available online: https://hope.be/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/Using-Evidence-in-Healthcare-Management-HOPE-Agora-2022.pdf (accessed on 14 August 2025).

| Phase | Intervention Unit | Time |

|---|---|---|

| Preparatory | Selection of primary nurses by the head nurse according to their skills. | 1 week |

| Specific training for the primary nurses. | 4 weeks | |

| Training for the rest of the nursing team. | 4 weeks | |

| Implementation | Changing the care organization model | 2 weeks |

| Start recruiting patients | 2 weeks later | |

| Evaluation | Baseline on admission (T0) | Up to 48 h after admission |

| On discharge from the unit (T1) | On the day of discharge | |

| Follow-up (T2) | 30 days after discharge |

| Intervention N = 106 | Control N = 100 | p-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 76.4 (±7.4) | 75.7 (±7.0) | 0.498 | |

| Sex, N (%) | Male | 63 (59.4) | 53 (53.0) | 0.352 |

| Female | 43 (40.6) | 47 (47.0) | ||

| Education, N (%) | Basic | 50 (47.2) | 36 (36.0) | 0.133 |

| Secondary | 27 (25.5) | 24 (24.0) | ||

| Higher | 29 (27.4) | 40 (40.0) | ||

| Household N (%) | Spouse/partner | 72 (67.9) | 66 (66.0) | 0.689 |

| Children | 11 (10.4) | 8 (8.0) | ||

| Lives alone | 23 (21.7) | 26 (26.0) | ||

| Caregiver N (%) | Spouse/partner | 51 (48.1) | 48 (48.0) | 0.334 |

| Children | 26 (24.5) | 32 (32.0) | ||

| Without a caregiver | 29 (27.4) | 20 (20.0) | ||

| Length of stay, mean (SD) | 8.7 (±7.0) | 6.7 (±5.1) | 0.020 | |

| Reason for hospitalization, N (%) | Circulatory system diseases | 26 (24.5) | 16 (16.0) | <0.001 |

| Respiratory system diseases | 31 (29.3) | 16 (16.0) | ||

| Digestive system diseases | 12 (11.3) | 11 (11.0) | ||

| Genitourinary system diseases | 15 (14.2) | 7 (7.0) | ||

| Diseases of the skin and subcutaneous tissue/Diseases of the musculoskeletal system and connective tissue | 5 (4.7) | 38 (38.0) | ||

| Other | 17 (16.0) | 12 (12.0) | ||

| Number of chronic diseases selected for the study, N (%) | One disease | 2 (1.9) | 15 (15.0) | 0.002 |

| Two diseases | 56 (52.8) | 45 (45.0) | ||

| Three diseases | 32 (30.2) | 33 (33.0) | ||

| Four diseases | 16 (15.1) | 7 (7.0) | ||

| Type of chronic diseases, N (%) | Circulatory system diseases | 57 (53.8) | 54 (54.0) | 0.172 |

| Diabetes Mellitus | 9 (8.5) | 16 (16.0) | ||

| Neoplasms | 19 (17.9) | 19 (19.0) | ||

| Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Diseases | 21 (19.8) | 11 (11.0) | ||

| Presence of other chronic conditions, N (%) | Yes | 70 (66.0) | 63 (63.0) | 0.649 |

| No | 36 (34.0) | 37 (37.0) | ||

| Self-Care | Intervention N = 106 M | Control N = 100 M | p-Value | Cohen’s D |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Global | 4.06 | 4.29 | 0.026 | −0.31 |

| Recognizing and managing signs and symptoms | 3.67 | 4.04 | 0.017 | −0.33 |

| Managing changes in health status | 4.15 | 4.28 | 0.245 | −0.13 |

| Managing medication | 4.44 | 4.67 | 0.053 | −0.22 |

| Self-Care | Intervention N = 106 M | Control N = 100 M | p-Value | Cohen’s D | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Global | Between admission and discharge | 0.21 | 0.01 | 0.024 | 0.32 |

| Between discharge and follow up | 0.27 | 0.19 | 0.363 | 0.13 | |

| Between admission and follow up | 0.48 | 0.21 | 0.008 | 0.32 | |

| Recognizing and managing signs and symptoms | Between admission and discharge | 0.36 | 0.09 | 0.037 | 0.29 |

| Between discharge and follow up | 0.28 | 0.22 | 0.581 | 0.08 | |

| Between admission and follow up | 0.64 | 0.31 | 0.033 | 0.30 | |

| Managing changes in health status | Between admission and discharge | 0.15 | −0.04 | 0.065 | 0.26 |

| Between discharge and follow up | 0.25 | 0.22 | 0.769 | 0.04 | |

| Between admission and follow up | 0.40 | 0.18 | 0.066 | 0.26 | |

| Managing medication | Between admission and discharge | 0.10 | −0.02 | 0.232 | 0.17 |

| Between discharge and follow up | 0.30 | 0.13 | 0.058 | 0.27 | |

| Between admission and follow up | 0.40 | 0.11 | 0.014 | 0.34 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gonçalves, I.; Almeida, S.; Jesus, É.; Nunes, E. Effect of the Primary Nursing Model on Self-Care Skills of Hospitalized Older Patients with Multimorbidity: A Quasi-Experimental Study. Healthcare 2025, 13, 2457. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13192457

Gonçalves I, Almeida S, Jesus É, Nunes E. Effect of the Primary Nursing Model on Self-Care Skills of Hospitalized Older Patients with Multimorbidity: A Quasi-Experimental Study. Healthcare. 2025; 13(19):2457. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13192457

Chicago/Turabian StyleGonçalves, Isabel, Sofia Almeida, Élvio Jesus, and Elisabete Nunes. 2025. "Effect of the Primary Nursing Model on Self-Care Skills of Hospitalized Older Patients with Multimorbidity: A Quasi-Experimental Study" Healthcare 13, no. 19: 2457. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13192457

APA StyleGonçalves, I., Almeida, S., Jesus, É., & Nunes, E. (2025). Effect of the Primary Nursing Model on Self-Care Skills of Hospitalized Older Patients with Multimorbidity: A Quasi-Experimental Study. Healthcare, 13(19), 2457. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13192457