Validating the Gender Variance Scale in Italian: Psychometric Properties and Associations with Health and Sociodemographic Factors

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Materials

2.3. Translation Procedure

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

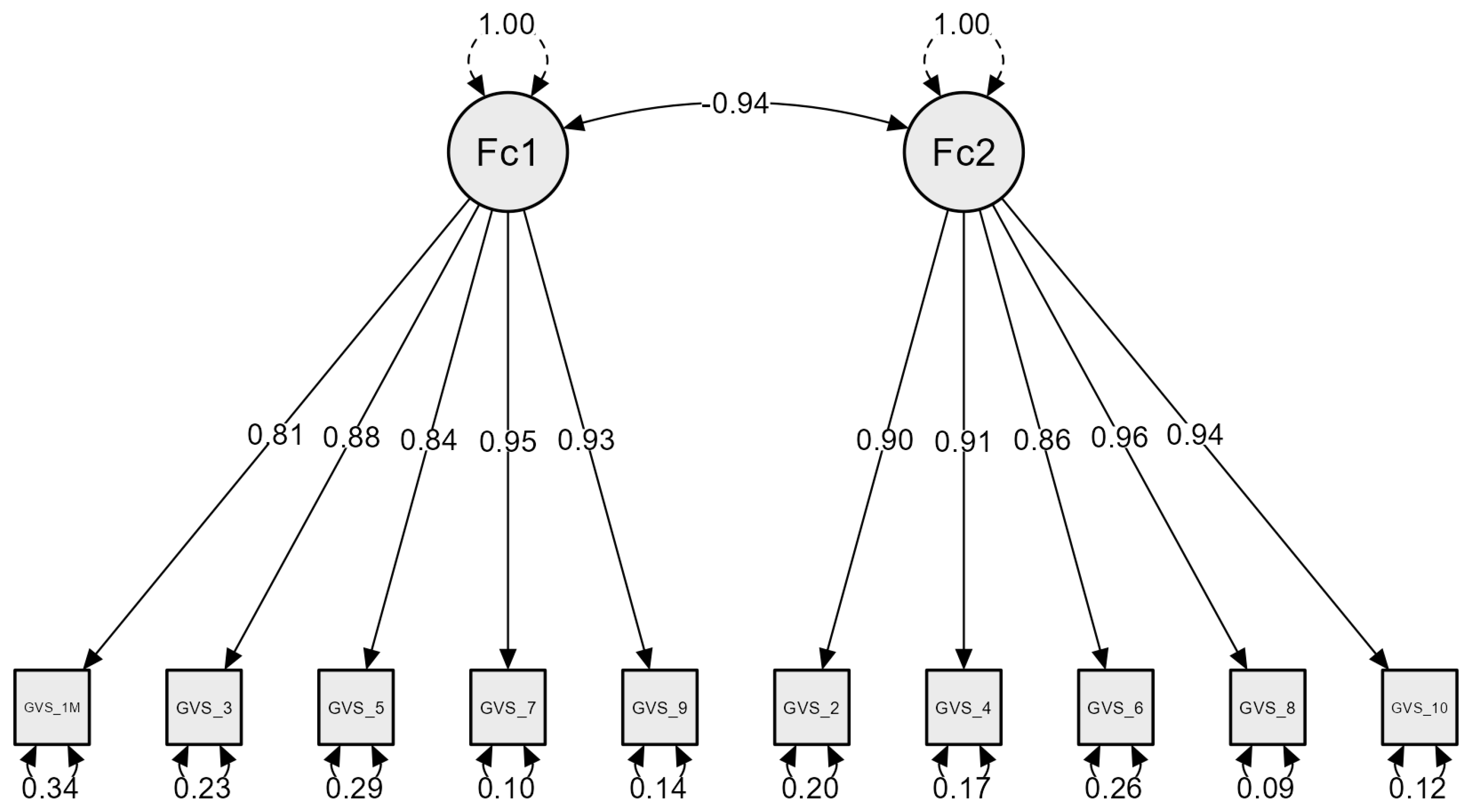

3.1. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

3.2. Convergent Validity with Health-Related Quality of Life

3.3. Group Differences in Gender Variance and Health Outcomes

3.4. Influence of Education and BMI on GVS Scores

3.5. Test–Retest Reliability

4. Discussion

4.1. Clinical and Research Implications

4.2. Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mazzuca, C.; Majid, A.; Lugli, L.; Nicoletti, R.; Borghi, A.M. Gender Is a Multifaceted Concept: Evidence That Specific Life Experiences Differentially Shape the Concept of Gender. Lang. Cogn. 2020, 12, 649–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirabella, M.; Piras, I.; Fortunato, A.; Fisher, A.D.; Lingiardi, V.; Mosconi, M.; Ristori, J.; Speranza, A.M.; Giovanardi, G. Gender Identity and Non-Binary Presentations in Adolescents Attending Two Specialized Services in Italy. J. Sex. Med. 2022, 19, 1035–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, C.; Bouman, W.P.; Seal, L.; Barker, M.J.; Nieder, T.O.; T’Sjoen, G. Non-Binary or Genderqueer Genders. Int. Rev. Psychiatry 2016, 28, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Combs, R. Gender Variance: The Intersection of Understandings Held in the Medical and Social Sciences. In Situating Intersectionality: Politics, Policy, and Power; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; pp. 131–155. [Google Scholar]

- Hsu, N.; Badura, K.L.; Newman, D.A.; Speach, M.E.P. Gender, “Masculinity,” and “Femininity”: A Meta-Analytic Review of Gender Differences in Agency and Communion. Psychol. Bull. 2021, 147, 987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, B.W.D.; Cohen-Kettenis, P.T.; Reed, T.; Spack, N. Medical Care for Gender Variant Young People: Dealing with the Practical Problems. Sexologies 2008, 17, 258–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vantieghem, W.; Van Houtte, M. The Impact of Gender Variance on Adolescents’ Wellbeing: Does the School Context Matter? J. Homosex. 2020, 67, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, W.I.; van der Miesen, A.I.R.; Shi, S.Y.; Ngan, C.L.; Lei, H.C.; Leung, J.S.Y.; VanderLaan, D.P. Gender Variance and Psychological Well-Being in Chinese Community Children. Psychol. Sex. Orientat. Gend. Divers. 2023, 11, 715–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychological Association. Guidelines for Psychological Practice with Transgender and Gender Nonconforming People. Am. Psychol. 2015, 70, 832–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scandurra, C.; Mezza, F.; Maldonato, N.M.; Bottone, M.; Bochicchio, V.; Valerio, P.; Vitelli, R. Health of Non-Binary and Genderqueer People: A Systematic Review. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yarrow, E.; Duschinsky, R.; Saunders, C.L. The Gender Variance Scale: Developing and Piloting a New Tool for Measuring Gender Diversity in Survey Research. J. Gend. Stud. 2024, 33, 244–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, C.; Bouman, W.P.; Barker, M. Non-Binary Genders. Lond. Pal Grave Macmillan 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farivar, S.S.; Cunningham, W.E.; Hays, R.D. Correlated Physical and Mental Health Summary Scores for the SF-36 and SF-12 Health Survey, V.1. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2007, 5, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salyers, M.P.; Bosworth, H.B.; Swanson, J.W.; Lamb-Pagone, J.; Osher, F.C. Reliability and Validity of the SF-12 Health Survey among People with Severe Mental Illness. Med. Care 2000, 38, 1141–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, I.; Ravens-Sieberer, U.; Ottová-Jordan, V.; Schulte-Markwort, M. Prevalence of Adolescent Gender Experiences and Gender Expression in Germany. J. Adolesc. Health 2017, 61, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Udugampolage, N.; Caruso, R.; Panetta, M.; Callus, E.; Dellafiore, F.; Magon, A.; Marelli, S.; Pini, A. Is SF-12 a Valid and Reliable Measurement of Health-Related Quality of Life among Adults with Marfan Syndrome? A Confirmatory Study. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0252864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kodraliu, G.; Mosconi, P.; Groth, N.; Carmosino, G.; Perilli, A.; Gianicolo, E.A.; Rossi, C.; Apolone, G. Subjective Health Status Assessment: Evaluation of the Italian Version of the SF-12 Health Survey. Results from the MiOS Project. J. Epidemiol. Biostat. 2001, 6, 305–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyde, J.S.; Bigler, R.S.; Joel, D.; Tate, C.C.; van Anders, S.M. The Future of Sex and Gender in Psychology: Five Challenges to the Gender Binary. Am. Psychol. 2019, 74, 171–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lefevor, G.T.; Boyd-Rogers, C.C.; Sprague, B.M.; Janis, R.A. Health Disparities between Genderqueer, Transgender, and Cisgender Individuals: An Extension of Minority Stress Theory. J. Couns. Psychol. 2019, 66, 385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frederick, D.A.; Gordon, A.R.; Cook-Cottone, C.P.; Brady, J.P.; Reynolds, T.A.; Alley, J.; Garcia, J.R.; Brown, T.A.; Compte, E.J.; Convertino, L.; et al. Demographic and Sociocultural Predictors of Sexuality-Related Body Image and Sexual Frequency: The U.S. Body Project I. Body Image 2022, 41, 109–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meneguzzo, P.; Zuccaretti, D.; Tenconi, E.; Favaro, A. Transgender Body Image: Weight Dissatisfaction, Objectification & Identity—Complex Interplay Explored via Matched Group. Int. J. Clin. Health Psychol. 2024, 24, 100441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meneguzzo, P.; Vozzi, L.; Biscaro, M.; Zuccaretti, D.; Tenconi, E.; Favaro, A. Internalized Transphobia and Body Image Concerns: A Cross-Sectional Comparison of Transgender and Gender Diverse Individuals before and after Gender-Affirming Therapy. Ital. J. Psychiatry 2024, 10, 112–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceolin, C.; Scala, A.; Scagnet, B.; Citron, A.; Vilona, F.; De Rui, M.; Miscioscia, M.; Camozzi, V.; Ferlin, A.; Sergi, G.; et al. Body Composition and Perceived Stress Levels in Transgender Individuals after One Year of Gender Affirming Hormone Therapy. Front. Endocrinol. 2024, 15, 1496160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Original (English) | Italian Translation | |

|---|---|---|

| Many people describe themselves and others as some combination of feminine (girlish) and masculine (boyish) because of how we feel, act, talk or dress. The next questions are about how you describe yourself. | Molte persone si descrivono, o descrivono gli altri, come una combinazione di femminile e maschile in base a come si sentono, si comportano, parlano o si vestono. Le prossime domande si riferiscono al modo in cui descrivi te stesso/a. | |

| 1 | On a scale of 1–9, where 1 means ‘not at all’, and 9 means ‘completely’, to what extent would you say that your interests are mostly those typical of a boy/young man/masculine person? | Su una scala da 1 a 9, dove 1 significa “per niente” e 9 significa “completamente”, in che misura i tuoi interessi sono tipicamente da maschio? |

| 2 | On a scale of 1–9, where 1 means ‘not at all’, and 9 means ‘completely’, to what extent would you say that your interests are mostly those typical of a girl/young woman/feminine person? | Su una scala da 1 a 9, dove 1 significa “per niente” e 9 significa “completamente”, in che misura i tuoi interessi sono tipicamente da femmina? |

| 3 | On a scale of 1–9, where 1 means ‘not at all’, and 9 means ‘completely’, to what extent would you say that you do most things in a manner of a boy/young man/masculine person? | Su una scala da 1 a 9, dove 1 significa “per niente” e 9 significa “completamente”, in che misura il tuo modo di fare sia tipicamente maschile? |

| 4 | On a scale of 1–9, where 1 means ‘not at all’, and 9 means ‘completely’, to what extent would you say that you do most things in a manner of a girl/young woman/feminine person? | Su una scala da 1 a 9, dove 1 significa “per niente” e 9 significa “completamente”, in che misura il tuo modo di fare sia tipicamente femminile? |

| 5 | On a scale of 1–9, where 1 means ‘not at all’, and 9 means ‘completely’, how masculine do you think you look? | Su una scala da 1 a 9, dove 1 significa “per niente” e 9 significa “completamente”, in che misura pensi di avere un aspetto mascolino? |

| 6 | On a scale of 1–9, where 1 means ‘not at all’, and 9 means ‘completely’, how feminine do you think you look? | Su una scala da 1 a 9, dove 1 significa “per niente” e 9 significa “completamente”, in che misura pensi di avere un aspetto femminile? |

| 7 | On a scale of 1–9, where 1 means ‘not at all’, and 9 means ‘completely’, how masculine do you feel? | Su una scala da 1 a 9, dove 1 significa “per niente” e 9 significa “completamente”, quanto ti senti maschile? |

| 8 | On a scale of 1–9, where 1 means ‘not at all’, and 9 means ‘completely’, how feminine do you feel? | Su una scala da 1 a 9, dove 1 significa “per niente” e 9 significa “completamente”, quanto ti senti femminile? |

| 9 | On a scale of 1–9, where 1 means ‘not at all’, and 9 means ‘completely’, how male do you feel? | Su una scala da 1 a 9, dove 1 significa “per niente” e 9 significa “completamente”, quanto ti senti uomo? |

| 10 | On a scale of 1–9, where 1 means ‘not at all’, and 9 means ‘completely’, how female do you feel? | Su una scala da 1 a 9, dove 1 significa “per niente” e 9 significa “completamente”, quanto ti senti donna? |

| 11 | What was your sex registered at birth (The sex put on your birth certificate?) Male/Female | Qual è il tuo sesso registrato alla nascita (cioè quello indicato sui documenti di nascita)? Maschio/Femmina |

| Subscale | Group | M | SD | H | p | Post Hoc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Masculinity | Cisgender men | 38.80 | 4.63 | 247.49 | <0.001 | Trans men < Cis men (p < 0.001) Trans men < Cis women (p < 0.001) Non-binary < Cis men (p < 0.001) Trans women < Cis men (p < 0.001) Trans men < Trans women (p = 0.002) Non-binary < Cis women (p < 0.001) Trans women < Cis women (p < 0.001) |

| Cisgender women | 34.96 | 6.32 | ||||

| Transgender men | 12.89 | 8.24 | ||||

| Transgender women | 21.28 | 8.71 | ||||

| Non-binary | 13.25 | 9.16 | ||||

| Femininity | Cisgender men | 9.85 | 5.60 | 238.48 | <0.001 | Trans women < Cis women (p < 0.001) Trans women < Trans men (p < 0.001) Trans women < Non-binary (p < 0.001) Cis men < all others (all p < 0.001) Non-binary < Cis women (p < 0.001) Non-binary < Trans men (p = 0.007) |

| Cisgender women | 36.78 | 5.13 | ||||

| Transgender men | 33.10 | 7.04 | ||||

| Transgender women | 12.17 | 6.77 | ||||

| Non-binary | 17.80 | 10.02 | ||||

| GVS Total | Cisgender men | 11.05 | 5.19 | 71.64 | <0.001 | Trans women > Cis men (p < 0.001) Trans men > Cis men (p < 0.001) Cis women > Cis men (p = 0.004) Non-binary < Cis women (p < 0.001) Non-binary < Trans women (p < 0.001) Non-binary < Trans men (p < 0.001) |

| Cisgender women | 16.47 | 9.54 | ||||

| Transgender men | 20.21 | 10.68 | ||||

| Transgender women | 23.17 | 10.59 | ||||

| Non-binary | 7.64 | 5.73 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Meneguzzo, P.; Dal Brun, D.; Tenconi, E.; Bonato, M.; Scala, A.; Miscioscia, M.; Garolla, A.; Favaro, A. Validating the Gender Variance Scale in Italian: Psychometric Properties and Associations with Health and Sociodemographic Factors. Healthcare 2025, 13, 2438. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13192438

Meneguzzo P, Dal Brun D, Tenconi E, Bonato M, Scala A, Miscioscia M, Garolla A, Favaro A. Validating the Gender Variance Scale in Italian: Psychometric Properties and Associations with Health and Sociodemographic Factors. Healthcare. 2025; 13(19):2438. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13192438

Chicago/Turabian StyleMeneguzzo, Paolo, David Dal Brun, Elena Tenconi, Marina Bonato, Alberto Scala, Marina Miscioscia, Andrea Garolla, and Angela Favaro. 2025. "Validating the Gender Variance Scale in Italian: Psychometric Properties and Associations with Health and Sociodemographic Factors" Healthcare 13, no. 19: 2438. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13192438

APA StyleMeneguzzo, P., Dal Brun, D., Tenconi, E., Bonato, M., Scala, A., Miscioscia, M., Garolla, A., & Favaro, A. (2025). Validating the Gender Variance Scale in Italian: Psychometric Properties and Associations with Health and Sociodemographic Factors. Healthcare, 13(19), 2438. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13192438