Mental Health Exploration and Variables Associated with Young Health Professionals in Early Childhood Care Centers: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Resources and Research Strategies

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

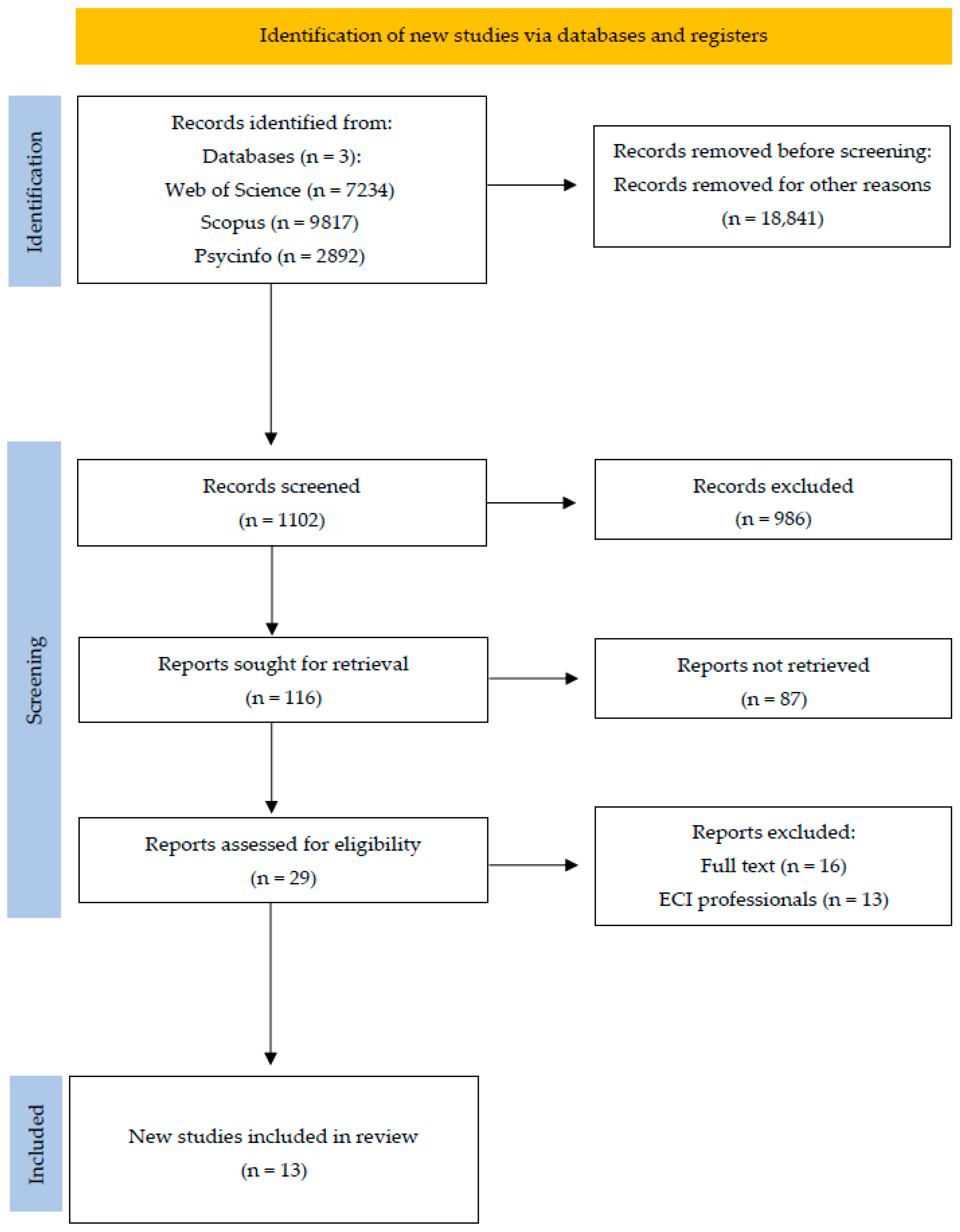

2.3. Study Selection Procedure

2.4. Data Analysis

2.5. Study Risk of Bias Assessment

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Clinical Implications for Young Professionals in Early Childhood Care

4.2. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Invertir en Salud Mental [Investing in Mental Health]. 2004. Available online: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/42897/9243562576.pdf?%20sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- Pan American Health Organization. Informe Mundial Sobre la Salud Mental: Transformar la Salud Mental Para Todos [World Mental Health Report: Transforming Mental Health for All]. Available online: https://doi.org/10.37774/9789275327715 (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- Robles-Bello, M.A.; Sánchez-Teruel, D. Atención Infantil Temprana en España [Early Childhood Care in Spain]. Pap. Psicol. 2013, 34, 132–143. [Google Scholar]

- Delgado, N.; Delgado, J.; Betancort, M.; Bonache, H.; Harris, L.T. What is the link between different components of empathy and burnout in healthcare professionals? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2023, 16, 447–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Losa-Iglesias, M.E.; De Bengoa, R.B. Prevalence and Relationship Between Burnout, Job Satisfaction, Stress, and Clinical Manifestatitons in Spanish Critical Care Nurses. Dimens. Crit. Care Nurs. 2013, 3, 130–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Carmen, M.G.; Herman, J.; Rao, S. Trends and Factors Associated with Physician Burnout at a Multispecialty Academic Faculty Practice Organization. JAMA 2019, 2, e199914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willard-Grace, R.; Knox, M.; Huang, B.; Hammer, H.; Kivlahan, C.; Grumbach, K. Burnout and Health Care Workforce Turnouver. Ann. Fam. Med. 2019, 1, 36–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, K.; Neff, D.M.; Pitman, S. Burnout in mental health professionals: A systematic review and meta-analysis of prevalence and determinants. Eur. Psychiatry 2018, 53, 74–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, Y.H. The meaning of early intervention: A parent’s experience and reflection on interactions with professionals using a phenomenological ethnographic approach. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Health Well-Being 2015, 10, 25891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, J.; Nguyen, T. Keeping Kids in Care: Reducing Administrative Burden in State Child Care Development Fund Policy. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2021, 32, 23–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuenca-Sánchez, L.; Sánchez-Teruel, D.; Robles-Bello, M.A. Experiences and Challenges of Health Professionals in Implementing Family-Centred Planning: A Qualitative Study. Children 2024, 11, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calero-Plaza, J.; Grau-Sevilla, M.D.; Martínez-Rico, G.; Morales-Murillo, C.P. Parenting Stress and Coping Strategies in Mothers of Children Receiving Early Intervention Services. J. Child. Fam. Stud. 2017, 26, 3192–3202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goedeke, S.; Shepherd, D.; Landon, J.; Taylor, S. How perceived support relates to child autismo symptoms and care-related stress in parents caring for a child with autism. Res. Autism Spectr. Disord. 2019, 60, 36–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, C. El Estrés en Familias con Sujetos con Deficiencia Intelectual [Stress in Families with Intellectually Impaired Subjects]. Ph.D. Thesis, Complutense University of Madrid, Madrid, Spain, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Robles-Bello, M.A.; Sánchez-Teruel, D. Psychometric properties of the Spanish version of the Family-Centred Practice Scale for use with families with children with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2021, 121, 105863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinn, E.L.; Stover, B.; Otten, J.J.; Seixas, N. Early Care and Education Workers’ Experience and Stress during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 2670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nevalainen, M.; Kuikka, L.; Pitkälä, K. Medical errors and uncertainty in primary healthcare: A comparative study of coping strategies among Young and experienced GPs. Scand. J. Prim. Health Care 2014, 32, 84–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robles-Bello, M.A.; Sánchez-Teruel, D. The Family-Centred Practices Scale: Psychometric properties of the Spanish version for use with families with children with Down syndrome receiving early childhood intervention. Child. Care Health Dev. 2022, 48, 634–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinze, K.E.; Hanson, G.; Holtz, H.; Swoboda, S.M.; Rushton, C.H. Measuring health care interprofessionals’ moral resilience: Validation of the Rushton Moral Resilience Scale. J. Palliat. Med. 2021, 24, 865–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Costa, S.; Páez, D.; Oriol, X.; Sánchez, F.; Gondim, S. Estructura de la escala de regulación emocional (MARS) y su relación con creatividad y la creatividad emocional: Un estudio en trabajadores españoles y latinoamericanos. In Inteligencia Emocional y Bienestar II, 1st ed.; Soler, J.L., Aparicio, L., Díaz, O., Escolano, E., Rodríguez, A., Eds.; Universidad San Jorge: Zaragoza, Spain, 2016; Volume 1, pp. 461–474. [Google Scholar]

- Bar-On, R. The Bar-On model of emotional-social intelligence. Psicothema 2006, 18, 13–25. [Google Scholar]

- Masten, A.S. Resilience in developing systems: Progress and promise as the fourth wave rises. Dev. Psychopathol. 2007, 19, 921–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoşgör, H.; Yaman, M. Investigation of the relationship between psychological resilience and job performance in Turkish nurses during the COVID-19 pandemic in terms of descriptive characteristics. J. Nurs. Manag. 2022, 30, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Delivering Quality Health Services: A Global Imperative for Universal Health Coverage. 2019. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241513906 (accessed on 18 June 2025).

- Nightingale, S.; Spiby, H.; Sheen, K.; Slade, P. The impact of emotional intelligence in health care professionals on caring behaviour towards patients in clinical and longterm care settings: Findings from an integrative review. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2018, 80, 106–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mealer, M.; Jones, J.; Newman, J.; McFann, K.K.; Rothbaum, B.; Moss, M. The presence of resilience is associated with a healthier psychological profile in intensive care unit (ICU) nurses: Results of a national survey. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2012, 49, 292–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacaksiz, F.E.; Tuna, R.; Seren, A.K.H. The correlation between organizational cynicism and performance in healthcare staff: A research on nurses. Acıbadem Univ. Sağlık Bilim. Derg. 2018, 9, 52–58. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory, 1st ed.; Martínez Roca: Barcelona, Spain, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. Self-Efficacy in Changing Societies, 1st ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Jex, S.M.; Bliese, P.D.; Buzzell, S.; Primeau, J. The impact of self-efficacy on stressor-strain relations: Coping style as an exploratory mechanism. J. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 86, 401–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jex, S.M.; Bliese, P.D. Efficacy beliefs as a moderator of the impact of work-related stressors: A multinivel study. J. Appl. Psychol. 1999, 84, 349–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grau, R.; Salanova, M.; Peiró, J.M. Efectos moduladores de la autoeficacia en el estrés laboral [Modulatory Effects of Self-efficacy on work stress]. Apunt. Psicol. 2000, 18, 57–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salanova, M.; Llorens, S.; Cifre, E.; Martínez, I.; Schaufeli, W.B. perceived Collective Efficacy, Subjective Well-Being and Task Performance among Electronic Work Groups: An Experimental Study. Small Group. Res. 2003, 34, 43–73. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. Self-Efficacy: The Exercise of Control, 1st ed.; Freeman: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Gil-Monte, P.R.; Núñez-Román, E.; Selva-Santoyo, Y. Relación entre el Síndrome de Quemarse por el trabajo (burnout) y Síntomas Cardiovasculares: Un estudio en Técnicos de Prevención de Riesgos Laborales [Relationship between burnout syndrome and cardiovascular symptoms: A study in occupational risk prevention technicians]. Rev. Interam. Psicol. 2006, 40, 227–232. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, T.R.; Lyons, J.B.; Khazon, S. Emotional intelligence and resilience. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2013, 55, 909–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salovey, P.; Sluyter, D.J. (Eds.) What is emotional intelligence? In Emotional Development and Emotional Intelligence: Educational Implications, 1st ed.; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1997; pp. 3–34. [Google Scholar]

- Goleman, D.; Cherniss, C. The Emotionally Intelligent Workplace, 1st ed.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Solano, A. Inteligencia Emocional en el trabajo: Sus implicaciones y el rol de la psicología laboral [Emotional Intelligence at work: Its implications and the role of work psychology]. Humanitas 2013, 10, 201–214. [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz, A.P.; Chaves, L. La empatía ¿un concepto unívoco? [Empathy, a univocal concept]. Rev. Cienc. Soc. 2013, 16, 123–146. [Google Scholar]

- Chaitoff, A.; Sun, B.; Windover, A.; Bokar, D.; Featherall, J.; Rothberg, M.B.; Misra-Hebert, A.D. Associations between physician empathy, physician characteristics, and standardized measures of patient experience. Acad. Med. 2017, 92, 1464–1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillot-Valdés, M.; Cuenca-Sánchez, L.; Sarhani-Robles, A.; Sánchez-Teruel, D.; Serra, L.; Robles-Bello, M.A. Qualitative study on the perceptions and experiences of parents in early intervention centres in relation to family-centred practices. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2025, 171, 108196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-García, A.M. Personalidad, Afrontamiento y Apoyo Social [Personality, Coping and Social Support], 1st ed.; UNED-Klinik: Madrid, Spain, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-García, A.M. Personalidad y enfermedad. In Psicología de la Personalidad, 1st ed.; Bermúdez, J., Pérez-García, A.M., Ruiz, J.A., Sanjuán, P., Rueda, B., Eds.; UNED: Madrid, Spain, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Avendaño, C.; Bustos, P.; Espinoza, P.M.; García, F.E.; Pierart, T. Burnout y Apoyo Social en Personal del Servicio de Psiquiatría de un Hospital Público [Burnout and Social Support in Staff of the Psychiatry Service of a Public Hospital]. Cienc. Enferm. 2009, 15, 55–68. [Google Scholar]

- Orgambídez-Ramos, A.; Borrego-Alés, Y. Apoyo social y engagement como antecedentes de la satisfacción laboral en personal de enfermería [Social Support and Engagement as Antecedents of Job Satisfaction in Nursing Staff]. Enferm. Glob. 2017, 16, 208–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galán-Vera, I.; Robles-Bello, M.A.; Sarhani-Robles, A.; Valencia-Naranjo, N. Experiences and coping strategies of parents with children diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder in early care with emphasis on social skills and family cultural values: A qualitative study. Arch. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2025, 56, 151864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; Moher, D.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. PRISMA 2020: Explanation and elaboration: Updated guidance and examples for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, G.A.; Shea, B.; O’Connell, D.; Peterson, J.; Welch, V.; Losos, M.; Tugwell, P. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for Assessing the Quality of Nonrandomised Studies in Meta-Analyses; Ottawa Hospital Research Institute: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Alameddine, M.; Bou-Karroum, K.; Hijazi, M.A. A national study on the resilience of community pharmacists in Lebanon: A cross-sectional survey. J. Pharm. Policy Pract. 2022, 15, 8. [Google Scholar]

- Alwhaibi, M.; Alhawassi, T.M.; Balkhi, B.; Al Aloola, N.; Almomen, A.A.; Alhossan, A.; Alyousif, S.; Almadi, B.; Bin Essa, M.; Kamal, K.M. Burnout and Depressive Symptoms in Healthcare Professionals: A Cross-Sectional Study in Saudi Arabia. Healthcare 2022, 10, 2447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alyahya, S.; AboGazalah, F. Work-Related Stressors among the Healthcare Professionals in the Fever Clinic Centers for Individuals with Symptoms of COVID-19. Healthcare 2021, 9, 548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayuso-Murillo, D.; Colomer-Sánchez, A.; Santiago-Magdalena, C.R.; Lendínez-Mesa, A.; Gracia, E.B.; López-Peláez, A.; Herrera-Peco, I. Effect of Anxiety on Empathy: An Observational Study Among Nurses. Healthcare 2020, 8, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delafontaine, A.C.; Anders, R.; Mathieu, B.; Salathé, C.R.; Putois, B. Impact of confrontation to patient suffering and death on wellbeing and burnout in professionals: A cross-sectional study. BMC Palliat. Care 2024, 23, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, P.A.; Denieffe, S.; Gooney, M. Running on empathy: Relationship of empathy to compassion satisfaction and compassion fatigue in cancer healthcare professionals. Eur. J. Cancer Care 2019, 28, e13124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, J.L.; Kuriyama, A.; Muramatsu, K. A Model of Burnout Among Healthcare Professionals. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2024, 39, 373–376. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, J.R.; Emmons, H.C.; Rivard, R.L.; Griffin, K.H.; Dusek, J.A. Resilience Training: A Pilot Study of a Mindfulness-Based Program with Depressed Healthcare Professionals. Explore 2015, 11, 433–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maffoni, M.; Sommovigo, V.; Giardini, A.; Velutti, L.; Setti, I. Well-Being and Professional Efficacy Among Health Care Professionals: The Role of Resilience Through the Mediation of Ethical Vision of Patient Care and the Moderation of Managerial Support. Eval. Health Prof. 2022, 45, 381–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathebula, L.C.; Filmalter, C.J.; Jordaan, J.; Heyns, T. Second victim experiences of healthcare providers after adverse events: A cross-sectional study. Health SA Gesondheid 2022, 27, 1858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridremont, D.; Boujut, E.; Dugas, E. Burnout profiles among French healthcare professionals caring for young cancer patients. Support. Care Cancer 2024, 32, e74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Almeida, S.R.; Costa, A.; Teixeira, I.; Trigueiro, M.J.; Dores, A.R.; Marques, A. Healthcare Professionals’ Resilience During the COVID-19 and Organizational Factors That Improve Individual Resilience: A Mixed-Method Study. Health Serv. Insights 2023, 16, 11786329231198991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, S.S.; Weiss, L.; Clayton, R.; Ruble, M.J.; Cole, J.D. The Relationship Between Pharmacist Resilience, Burnout, and Job Performance. J. Pharm. Pract. 2024, 37, 644–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The World Bank. World Bank Country and Lending Groups. Available online: https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519-world-bank-country-and-lending-groups (accessed on 16 June 2025).

| Criteria | Inclusion | Exclusion |

|---|---|---|

| Date of publication | 2014–2024 | Before 2014 or after April 2024 |

| Type of document | Quantitative research articles | Gray literature (websites, blogs) and review articles |

| Research area | Healthcare, mental health professionals, and young mental health professionals | Non-healthcare areas |

| Language | Articles in English and/or Spanish | Articles written in any language other than English and/or Spanish |

| Article focus | Articles focused on analyzing the relationship between mental health and healthcare professionals and/or the relationship between protective variables and healthcare professional | Articles that do not aim to analyze the relationship between mental health and protective factors in health professionals |

| Study | Selection | Comparability | Exposure | Total Quality Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alameddine [50] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 6 |

| Alwhaibi [51] | 3 | 2 | 2 | 7 |

| Alyahya and AboGazalah [52] | 3 | 2 | 2 | 7 |

| Ayuso-Murillo [53] | 2 | 1 | 2 | 5 |

| Delafontaine [54] | 3 | 2 | 2 | 7 |

| Hunt [55] | 3 | 2 | 2 | 7 |

| Jackson [56] | 2 | 1 | 2 | 5 |

| Johnson [57] | 4 | 2 | 3 | 9 |

| Maffoni [58] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 6 |

| Mathebula [59] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 6 |

| Ridremont [60] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 6 |

| de Almeida [61] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 6 |

| Weiss [62] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 6 |

| Author(s) | Year | Variables Studied | Participants | Methodology | Instruments Used | Relevant Conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alameddine [50] | 2022 | Predictor: resilience; outcome: burnout, job satisfaction, turnover intention, workload, pay, perception of safety | Pharmacists | Quantitative | CD-RISC; CBI; ad hoc | Lower levels of resilience are associated with higher levels of burnout |

| Alwhaibi [51] | 2022 | Correlational: depression, socio-demographic variables and burnout | Health professionals in hospital | Quantitative | PRIME-MD; MBI; ad hoc | Depression is characterized by burnout symptoms in the occupational setting. Interventions are needed to improve the mental health of healthcare professionals |

| Alyahya and AboGazalah [52] | 2021 | Predictor: stress; outcome: social support, work role conflict, work role ambiguity, work overload | Health professionals in primary care centers | Quantitative | PSS; MSPSS; the role ambiguity and the role conflict measure | Social support is associated with stress |

| Ayuso-Murillo [53] | 2020 | Correlational: empathy and anxiety | Nursing professionals in public hospitals | Quantitative | 16PF-5; ad hoc | Higher levels of anxiety negatively impact warmth, liveliness, social skills, and openness to change—symptoms that are closely associated with burnout |

| Delafontaine [54] | 2024 | Predictors: personality variables, meaning at work; outcome: anxiety, depression, burnout, well-being | Oncology and palliative care health professionals | Quantitative | MBI-HSS; IPWW; HADS; RSE; MS; TIPI; CSDS | Burnout is considered a defense mechanism against suffering and experiences related to death, and is often regarded as the antithesis of empathy |

| Hunt [55] | 2019 | Correlational: compassion satisfaction, secondary traumatic stress and burnout | Health professionals involved in the care of people with cancer | Quantitative | ProQOL-V; IRI; ad hoc | Higher stress levels are associated with increased burnout and secondary traumatic stress, leading to greater depression, reduced empathy, and poor communication |

| Jackson [56] | 2024 | Predictors: anxiety, depression and resilience; outcome: burnout | Critical care health professionals | Quantitative | Mini-Z; PHQ-9; GAD-7; BRS-J; ad hoc | Resilience decreases with depressive and anxious symptoms. Strengthening resilience, teamwork, and safety reduces burnout |

| Johnson [57] | 2015 | Predictor: resilience training program; outcome: depression, anxiety, perceived stress | Depressed health professionals | Quantitative | Intervention program | Enhancing resilience contributes to reduced depressive symptoms |

| Maffoni [58] | 2022 | Predictor: resilience; outcome: well-being, professional self-efficacy, ethical vision of patient care, managerial support | Health professionals involved in neuro-rehabilitation or palliative care | Quantitative | CD-RISC; MASI-R; MBI; ad hoc | Resilience shows a positive association with well-being and self-efficacy, contributing to improved quality of care |

| Mathebula [59] | 2022 | Correlational: second victim experience, stress, social support, self-efficacy, turnover intentions, absenteeism | Hospital professionals (including administrative staff) | Quantitative | SVEST | Professionals require active involvement from their supervisors. Adverse events are linked to decreased self-efficacy, increased turnover intentions, absenteeism, and stress symptoms |

| Ridremont [60] | 2024 | Correlational: burnout, work rewards, coping strategies, socio-demographic variables, quality of patient care | Health professionals (medicine, nursing and auxiliary nursing) dedicated to child and adolescent cancer care. | Quantitative | PCSQ; WRS-PO; WCC-R; MBI; ad hoc | Professional profiles vary according to stress levels and work rewards, indirectly affecting the quality of patient care |

| de Almeida [61] | 2023 | Correlational: resilience, social support, socio-demographic variables, working hours, overall health rating | Health professionals (medicine, nursing, psychology) | Quantitative and qualitative | Semi-structured interview; RSA; ad hoc | Social support benefits physical and mental health |

| Weiss [62] | 2024 | Predictor: resilience; outcome: burnout, job performance | Pharmacy professionals | Quantitative | BRS; CBI; ad hoc | Resilience negatively predicts burnout |

| Author (Year) | Country/Income Level | N 1 (Professional Profile) | Instruments | Estimators | Key Associations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alameddine (2022) [50] | Lebanon/upper–middle-income | 459 (pharmacists) | CD-RISC; CBI; ad hoc | CD-RISC: M = 68 (SD = 13.37); MBI: M = 56.51 (SD = 16.68) | Lower levels of resilience are associated with higher levels of burnout (β = 0.489; 95% CI, 0.282–0.849, p = 0.011) |

| Alwhaibi (2022) [51] | Saudi Arabia/high-income | 139 (health professionals in hospital) | PRIME-MD; MBI; ad hoc | MBI: EE 2 M = 31.60 (SD = 15.10); DP 3 M = 16.20 (SD = 9.70); PA 4 M = 31.50 (SD = 12.80); PRIME MD: depression (61.20%), non-depression (38.80%) | Participants with depression were significantly more likely to present high overall burnout compared to those without depression (20% vs. 16.90%; p < 0.001). |

| Alyahya and AboGazalah (2021) [52] | Saudi Arabia/high-income | 275 (health professionals in primary care centers) | PSS; MSPSS | Not reported | Social support is negatively associated with stress (β = −0.15; 95% CI, −0.149–−0.032, p < 0.01) |

| Ayuso-Murillo (2020) [53] | Spain/high-income | 197 (nursing professionals in public hospitals) | 16PF-5 | Anxiety: M = 6.38 (SD = 1.85); warmth: M = 5.58 (SD = 1.62); socially bold: M = 5.60 (SD = 1.74); open to change: M = 5.62 (SD = 1.40) | Anxiety is associated with warmth (t = 2.66, p > 0.0001), socially bold (t = −3.17, p < 0.001) and open to change (t = −5.81, p < 0.0001) |

| Delafontaine (2024) [54] | Switzerland/high-income | 109 (oncology and palliative care health professionals) | MBI; CSDS; TIPI | Not reported | Burnout is associated with positive impact on patient relations (β = −0.22; 95% CI, −0.38–−0.06, p = 0.007) and agreeableness (β = −0.18% CI, −0.34–−0.01, p = 0.03) |

| Hunt (2019) [55] | Ireland/high-income | 117 (health professionals involved in the care of people with cancer) | ProQOL-V; IRI | Not reported; Cronbach’s alpha: compassion satisfaction (0.88), personal distress (0.71), empathic concern (0.78) | Secondary traumatic stress is positively associated with empathic concern (r = 0.27, p < 0.006). Compassion satisfaction is negatively associated with personal distress (r = −0.37, p < 0.001) |

| Jackson (2024) [56] | Japan/high-income | 936 (critical care health professionals) | Mini-Z; PHQ-9; GAD-7; BRS-J; ad hoc | Not reported | Depression (β = −0.32, 95% CI −0.41–−0.23) and anxiety (β = −0.20, 95% CI 0.29–0.10) decreased resilience |

| Johnson (2015) [57] | United States/high-income | 40 (health professionals) | CESD-10 | Pre: CESD-10: M = 15.80 (SD = 5.01) | CESD-10 mean depression scores decreased 63% from 15.80 to 5.81 (p ≤ 0.01) in Resilience Training |

| Maffoni (2022) [58] | Italy/high-income | 315 (health professionals involved in neuro-rehabilitation or palliative care) | CD-RISC; MASI-R; MBI; ad hoc | Not reported | Resilience is positively associated with ethical vision of patient care (β = 0.17, 95% CI 0.09–0.31, p < 0.05), well-being (β = 0.48, 95% CI 0.18–0.54) and professional self-efficacy (β = 0.54, 95% CI 0.39–0.65, p < 0.001) |

| Mathebula (2022) [59] | South Africa/upper–middle-income | 181 (hospital professionals including administrative staff) | SVEST | Professional self-efficacy including administrative staff: M = 2.71 (SD = 0.94) | Adverse events affect professional self-efficacy (M = 2.51, SD = 0.98) |

| Ridremont (2024) [60] | France/high-income | 262 (medicine, nursing and auxiliary nursing professionals dedicated to child and adolescent cancer care) | PCSQ | PCSQ: M = 10.30 (SD = 1.70) | Significant differences between profiles on total stress score (F = 22.05, p < 0.001), stress related to working conditions (W = 31.46, p < 0.001), stress related to relationships with patients and families (F = 4.25, p < 0.01), stress related to confrontation with suffering and death (F = 3.30, p < 0.01), and stress related to relationships with colleagues and superiors (F = 8.59, p < 0.001). |

| de Almeida (2023) [61] | Portugal/high-income | 271 (medicine, nursing and psychology) | RSA | RSA: M = 178.17 (SD = 22.44) | Medical doctors and psychologists present the highest levels in total resilience (p = 0.018) |

| Weiss (2024) [62] | United States/high-income | 942 (pharmacy professionals) | BRS; CBI | BRS: M = 3.60 (SD = 0.71); CBI: M = 3.22 (SD = 0.92) | Resilience significantly predicted both burnout (β = −0.701, p < 0.001) and job performance (β = 0.35, p < 0.001) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gómez-Herrera, S.; Robles-Bello, M.A.; Sánchez-Teruel, D. Mental Health Exploration and Variables Associated with Young Health Professionals in Early Childhood Care Centers: A Systematic Review. Healthcare 2025, 13, 2354. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13182354

Gómez-Herrera S, Robles-Bello MA, Sánchez-Teruel D. Mental Health Exploration and Variables Associated with Young Health Professionals in Early Childhood Care Centers: A Systematic Review. Healthcare. 2025; 13(18):2354. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13182354

Chicago/Turabian StyleGómez-Herrera, Sofía, María Auxiliadora Robles-Bello, and David Sánchez-Teruel. 2025. "Mental Health Exploration and Variables Associated with Young Health Professionals in Early Childhood Care Centers: A Systematic Review" Healthcare 13, no. 18: 2354. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13182354

APA StyleGómez-Herrera, S., Robles-Bello, M. A., & Sánchez-Teruel, D. (2025). Mental Health Exploration and Variables Associated with Young Health Professionals in Early Childhood Care Centers: A Systematic Review. Healthcare, 13(18), 2354. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13182354