Exploring the Impact of Health Literacy on Fertility Awareness and Reproductive Health in University Students—A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

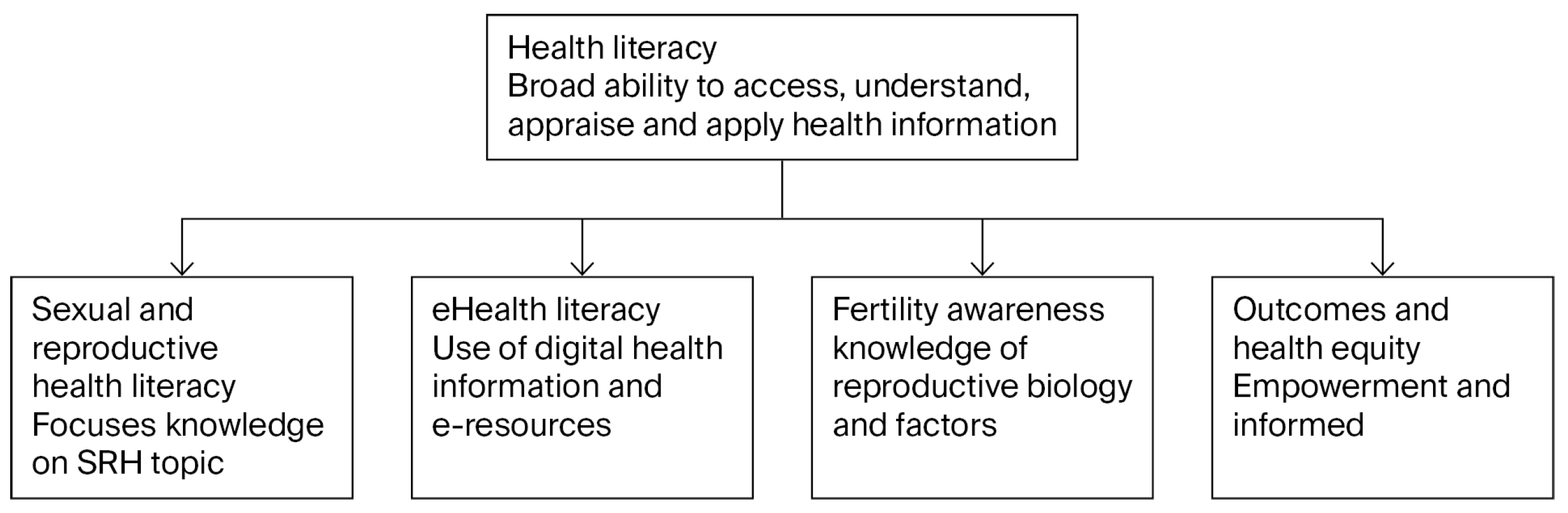

Conceptual Framework

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sources

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Search Strategy

2.4. Study Selection

2.5. Quality Appraisal

2.6. Data Abstraction and Analysis

3. Results

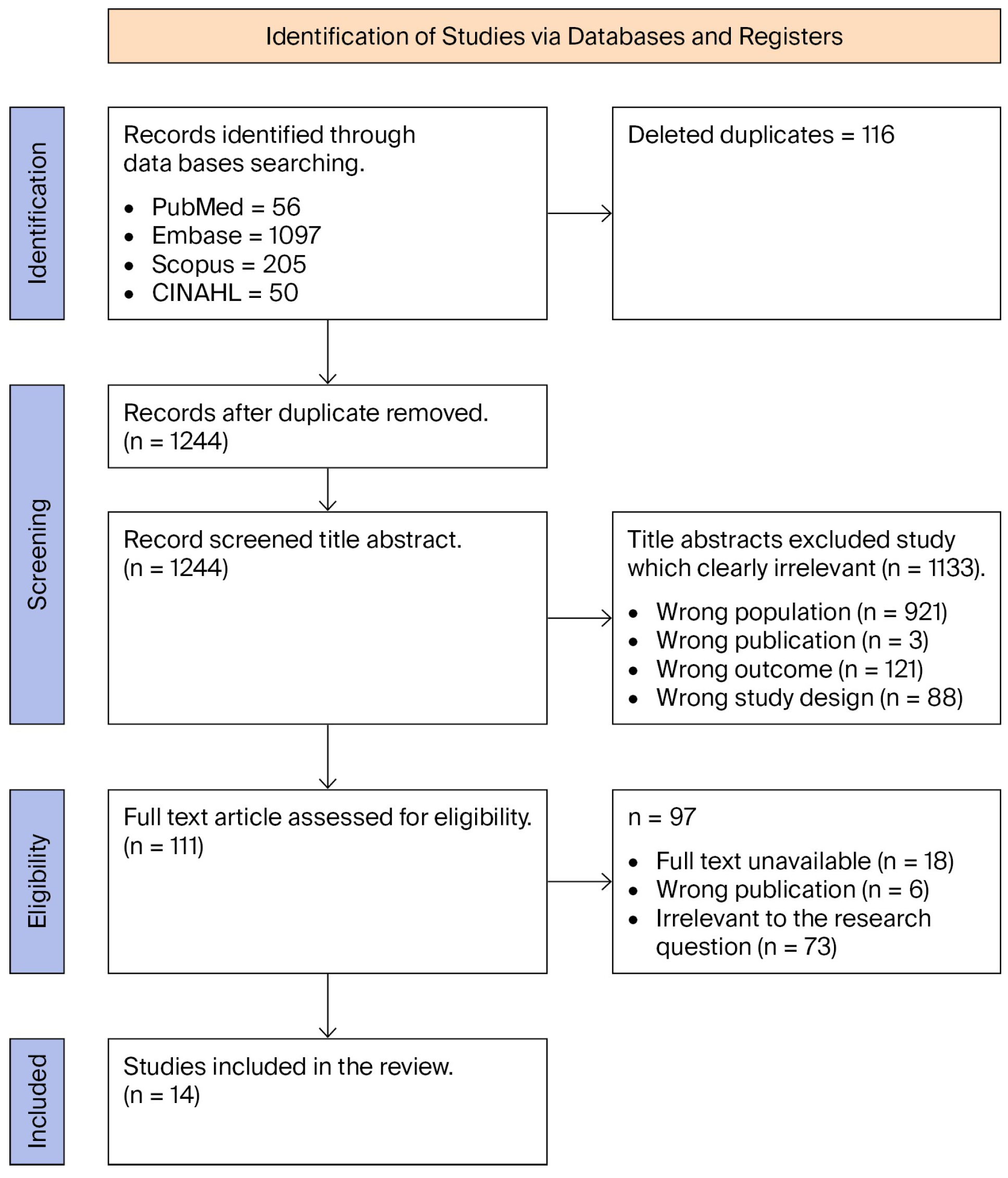

3.1. Yield of Database Search

3.2. Characteristics of Included Studies

3.3. Measurement Tools Used in Included Studies

3.4. The Main Findings from Included Studies

3.5. Health Literacy and Knowledge

3.6. Influence of Socioeconomic Factors

3.7. Gender Differences in Health Literacy

3.8. Impact of Education Intervention on Health Literacy

3.9. Technology and E-Health Literacy

3.10. Cultural and Contextual Influences

3.11. Health Literacy Levels and Associated Behaviours

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

6. Limitations

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PROSPERO | Prospective Register for Systematic Reviews |

| REALM | Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Medicine |

| HLQ | Health Literacy Questionnaire |

| PRISMA | Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| IQR | Interquartile range |

| HLS-EU | European Health Literacy Project Questionnaire |

| NVS | Newest Vital Sign |

| FA | Fertility Awareness |

| STROBE | Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology |

| MMAT | Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool |

References

- Gani, I.; Ara, I.; Dar, M.A. Reproductive Health of Women: A comprehensive review. Int. J. Curr. Res. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2023, 7, 11–25. [Google Scholar]

- Ara, I.; Maqbool, M.; Gani, I. Reproductive Health of Women: Implications and attributes. Int. J. Curr. Res. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2022, 6, 8–18. [Google Scholar]

- Van Gerwen, O.T.; Muzny, C.A.; Marrazzo, J.M. Sexually transmitted infections and female reproductive health. Nat. Microbiol. 2022, 7, 1116–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hock, M.; Tóth, S.; Hartmann, G.; Hartmann, T.; Bódis, J.; Garai, J. Quality of life, sexual functions and urinary incontinence after hysterectomy in Hungarian women. Am. J. Health Res. 2015, 3, 393–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Åsberg, K.; Eldh, A.C.; Löf, M.; Bendtsen, M. A balancing act–finding one s way to health and well-being: A qualitative analysis of interviews with Swedish university students on lifestyle and behavior change. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0275848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yak, E. Improving the Reproductive Health of the Student Community-the Case of the Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Kumasi, Ghana; Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology: Kumasi, Ghana, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Rod, N.H.; Davies, M.; de Vries, T.R.; Kreshpaj, B.; Drews, H.; Nguyen, T.-L.; Elsenburg, L.K. Young adulthood: A transitional period with lifelong implications for health and wellbeing. BMC Glob. Public Health 2025, 3, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.; Xie, Y.; Xu, Q.; Long, M.; Zheng, Y.; Li, L.; Niu, C. University students’ fertility awareness and its influencing factors: A systematic review. Reprod. Health 2023, 20, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chawhanda, C.; Levin, J.; Ibisomi, L. Factors associated with sexual and reproductive health service utilisation in high migration communities in six Southern African countries. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedro, J.; Brandão, T.; Schmidt, L.; Costa, M.E.; Martins, M.V. What do people know about fertility? A systematic review on fertility awareness and its associated factors. Upsala J. Med. Sci. 2018, 123, 71–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hampton, K.D.; Mazza, D.; Newton, J.M. Fertility-awareness knowledge, attitudes, and practices of women seeking fertility assistance. J. Adv. Nurs. 2013, 69, 1076–1084. [Google Scholar]

- Ayoola, A.B.; Zandee, G.L.; Adams, Y.J. Women’s knowledge of ovulation, the menstrual cycle, and its associated reproductive changes. Birth 2016, 43, 255–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghanbari, S.; Ramezankhani, A.; Montazeri, A.; Mehrabi, Y. Health literacy measure for adolescents (HELMA): Development and psychometric properties. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0149202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coughlin, S.S.; Vernon, M.; Hatzigeorgiou, C.; George, V. Health literacy, social determinants of health, and disease prevention and control. J. Environ. Health Sci. 2020, 6, 3061. [Google Scholar]

- Berkman, N.D.; Sheridan, S.L.; Donahue, K.E.; Halpern, D.J.; Crotty, K. Low health literacy and health outcomes: An updated systematic review. Ann. Intern. Med. 2011, 155, 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newton, V.L.; Dickson, J.; Hoggart, L. Young women’s fertility knowledge: Partial knowledge and implications for contraceptive risk-taking. BMJ Sex. Reprod. Health 2020, 46, 147–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alhussaini, N.W.Z.; Elshaikh, U.; Abdulrashid, K.; Elashie, S.; Hamad, N.A.; Al-Jayyousi, G.F. Sexual and reproductive health literacy of higher education students: A scoping review of determinants, screening tools, and effective interventions. Glob. Health Action 2025, 18, 2480417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kilfoyle, K.A.; Vitko, M.; O’Conor, R.; Bailey, S.C. Health literacy and women’s reproductive health: A systematic review. J. Women’s Health 2016, 25, 1237–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dózsa-Juhász, O.; Makai, A.; Prémusz, V.; Ács, P.; Hock, M. Investigation of premenstrual syndrome in connection with physical activity, perceived stress level, and mental status—A cross-sectional study. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1223787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, M.K. The Development and Evaluation of the Healthy Beverage Index for US Children and Adolescents. Master’s Thesis, Virginia Tech, Blacksburg, VA, USA, 14 May 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Guan, M. Sexual and reproductive health knowledge, sexual attitudes, and sexual behaviour of university students: Findings of a Beijing-Based Survey in 2010–2011. Arch. Public Health 2021, 79, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mowson, R.E. Reproductive Health Seeking Behaviors Among Female University Students: An Action Oriented Exploratory Study; University of South Florida: Tampa, FL, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Sons, A.; Eckhardt, A.L. Health literacy and knowledge of female reproduction in undergraduate students. J. Am. Coll. Health 2023, 71, 836–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sathe, R.; Amabile, C.; Brewer, C.; Song, K.; Athwal, S.; Wani, M.; Macam, S.; Wagman, J.A.; Swendeman, D. Understanding sexual and reproductive healthcare-seeking behaviors of college students at University of California’s on-campus health clinic. J. Am. Coll. Health 2025, 73, 2149–2157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mwamba, B.; Mayers, P.; Shea, J. Sexual and reproductive health knowledge of postgraduate students at the University of Cape Town, in South Africa. Reprod. Health 2022, 19, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Chen, K.; Wang, S.; Wang, W.; Li, Y. Initial validation of a Chinese version of the mental health literacy scale among Chinese teachers in Henan province. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 661903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vamos, C.A.; Thompson, E.L.; Logan, R.G.; Griner, S.B.; Perrin, K.M.; Merrell, L.K.; Daley, E.M. Exploring college students’ sexual and reproductive health literacy. J. Am. Coll. Health 2020, 68, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lirios, A.; Mullens, A.B.; Daken, K.; Moran, C.; Gu, Z.; Assefa, Y.; Dean, J.A. Sexual and reproductive health literacy of culturally and linguistically diverse young people in Australia: A systematic review. Cult. Health Sex. 2024, 26, 790–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patton, G.C.; Sawyer, S.M.; Santelli, J.S.; Ross, D.A.; Afifi, R.; Allen, N.B.; Arora, M.; Azzopardi, P.; Baldwin, W.; Bonell, C.; et al. Our future: A Lancet commission on adolescent health and wellbeing. Lancet 2016, 387, 2423–2478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, H.M.; Ridgeway, K.; Murray, K.; Mickler, A.; Thomas, R.; Williams, K. Reproductive empowerment and contraceptive self-care: A systematic review. Sex. Reprod. Health Matters 2022, 29, 2090057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urstad, K.H.; Andersen, M.H.; Larsen, M.H.; Borge, C.R.; Helseth, S.; Wahl, A.K. Definitions and measurement of health literacy in health and medicine research: A systematic review. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e056294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norman, C.D.; Skinner, H.A. eHEALS: The eHealth literacy scale. J. Med. Internet Res. 2006, 8, e27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stachowska, A.; Kicińska, A.M.; Wierzba, T.H. The History of Fertility Awareness Methods. Kwart. Nauk. Fides Ratio 2022, 51, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ouzzani, M.; Hammady, H.; Fedorowicz, Z.; Elmagarmid, A. Rayyan—A web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst. Rev. 2016, 5, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, Q.N.; Gonzalez-Reyes, A.; Pluye, P. Improving the usefulness of a tool for appraising the quality of qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods studies, the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT). J. Eval. Clin. Pract. 2018, 24, 459–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knottnerus, A.; Tugwell, P. STROBE--a checklist to Strengthen the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2008, 61, 323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chawłowska, E.; Lipiak, A.; Krzysztoszek, J.; Krupa, B.; Staszewski, R. Reproductive Health Literacy and Fertility Awareness Among Polish Female Students. Front. Public Health 2020, 8, 499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Small, E.; Nikolova, S.P.; Keyes, L.L.; Robinson, S.R. Sexual health literacy, parental education, and risky sexual behavior among college students in Sierra Leone. Cogent Soc. Sci. 2023, 9, 2279352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslantekin-Özcoban, F.; Gün, M. Emergency contraception knowledge level and e-health literacy in Turkish university students. Clin. Exp. Obstet. Gynecol. 2021, 48, 1424–1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manwong, M.; Thongnopakun, S.; Rodjarkpai, Y.; Wattanaburanon, A.; Visanuyothin, S. Sexual health literacy and preventive behaviors among middle-school students in a rural area during the COVID-19 situation: A mixed methods study. Health Promot. Perspect. 2022, 12, 178–185. [Google Scholar]

- Albright, A.E.; Allen, R.S. HPV misconceptions among college students: The role of health literacy. J. Community Health 2018, 43, 1192–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akoku, D.A.; Vukugah, T.A.; Tihnje, M.A.; Nzubepie, I.B. Childbearing intentions, fertility awareness knowledge and contraceptive use among female university students in Cameroon. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0276270. [Google Scholar]

- Arifah, I.; Safari, A.L.D.; Fieryanjodi, D. Health Literacy and Utilization of Reproductive Health Services Among High School Students. J. Promosi Kesehat. Indones. 2022, 17, 79–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohbet, R.; Geçici, F. Examining the level of knowledge on sexuality and reproductive health of students of Gaziantep University. Sex. Disabil. 2014, 32, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, A.; Eckert, T.L.; Zaso, M.J.; Scott-Sheldon, L.A.; Vanable, P.A.; Carey, K.B.; Ewart, C.K.; Carey, M.P. Associations between health literacy and health behaviors among urban high school students. J. Sch. Health 2017, 87, 885–893. [Google Scholar]

- Taşçı, E.Ş.; Baş, D.; Kayak, S.; Anık, S.; Erözcan, A.; Sönmez, Ö. Assessment of health literacy and HPV knowledge among university students: An observational study. Medicine 2024, 103, e39495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Narkarat, P.; Taneepanichskul, S. Factor associated with sexual health literacy among secondary school female students in the southern province of Thailand. J. Med. Assoc. Thail. 2021, 104, 1020–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sürmeli, Y.; Yıldırım, C.; Yüzbaşıoğlu, Ü.; Güldağ, Ö. The effect of sexual health education on sexual myths and sexual health literacy among University students. Afr. J. Reprod. Health 2024, 28, 112–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wardiati, W.; Septiani, R.; Agustina, A.; Ariscasari, P.; Arlianti, N.; Mairani, T. Reproductive Health Literacy of Adolescents at Public Islamic School: A Cross-Sectional Study in Indonesia. Al-Sihah Public Health Sci. J. 2023, 15, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farih, M.I. An exploratory study of sexual and reproductive health knowledge, information-seeking behaviour and attitudes among Saudi women: A questionnaire survey of university students. J. Community Med. Health Care 2017, 2, 1020. [Google Scholar]

- Muhlisa, M.; Amiruddin, R.; Moedjiono, A.I.; Suriah, S.; Damanik, R.; Salmah, U.; Nasir, S.; Areni, I.S.; Mallongi, A. Application-based Reproductive Health Education on Reproductive Health Risk Behavior among Adolescents in Ternate City. Pharmacogn. J. 2024, 16, 942–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.L.; Mumbengegwi, D.; Haindongo, E.; Cueto, C.; Roberts, K.W.; Gosling, R.; Uusiku, P.; Kleinschmidt, I.; Bennett, A.; Sturrock, H.J.; et al. Malaria risk factors in northern Namibia: The importance of occupation, age and mobility in characterizing high-risk populations. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0252690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ács, P.; Betlehem, J.; Oláh, A.; Bergier, J.; Melczer, C.; Prémusz, V.; Makai, A. Measurement of public health benefits of physical activity: Validity and reliability study of the international physical activity questionnaire in Hungary. BMC Public Health 2020, 20 (Suppl. 1), 1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arco, D.A.-D.; Fakoya, I.; Thomadakis, C.; Pantazis, N.; Touloumi, G.; Gennotte, A.-F.; Zuure, F.; Barros, H.; Staehelin, C.; Göpel, S.; et al. High levels of postmigration HIV acquisition within nine European countries. AIDS 2017, 31, 1979–1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prémusz, V.; Kovács, K.A.; Skriba, E.; Tándor, Z.; Szmatona, G.; Dózsa-Juhász, O. Socio-Economic and Health Literacy Inequalities as Determinants of Women’s Knowledge about Their Reproductive System: A Cross-Sectional Study. Epidemiologia 2024, 5, 627–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero-Núñez, J.; Jofré-Olivares, D.; Guillén-Grima, F.; Aguinaga-Ontoso, I.; Bacho-Tapia, A.; Araya-Moraga, L.; Iturrieta-Guaita, N.; Villanueva-Pabón, L.; Correa-Butrón, M.; Briones-Lorca, M.; et al. Literacy in sexual and reproductive health as well as associated variables: Multicenter study. Rev. Esp. Salud Publica 2024, 98, e202405035. [Google Scholar]

- Prémusz, V.; Makai, A.; Perjés, B.; Máté, O.; Hock, M.; Ács, P.; Koppán, M.; Bódis, J.; Várnagy, Á.; Lampek, K. Multicausal analysis on psychosocial and lifestyle factors among patients undergoing assisted reproductive therapy–with special regard to self-reported and objective measures of pre-treatment habitual physical activity. BMC Public Health 2021, 21 (Suppl. 1), 1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Search # | Search Terms |

|---|---|

| #1 | College Student* OR Student* OR University* OR Universities OR Higher Education OR Campus |

| #2 | Health Literacy |

| #3 | Fertility OR Fertility Awareness OR Fertility Knowledge OR Fertility Intentions OR Fecundability OR Fecundity OR Fertility Incentives OR Fertility Incentive OR World Fertility Survey OR Fertility Determinants OR Fertility Preferences OR Fertility Preference OR Reproductive Behaviour OR Childbearing OR Childbirth OR Reproductive Health Knowledge OR Fertility Education OR Conception Knowledge OR Reproductive Life Span OR Pregnancy Planning OR Fertility Literacy OR Reproductive Health |

| #4 | #1 AND #2 AND #3 |

| MMAT Parameters | Low Risk of Bias | Some Concern of Bias | High Level of Bias |

|---|---|---|---|

| Strong methodology with a substantial sample size. A clear description of variables and control for confounders. Robust statistical analysis. | 10 | 0 | 0 |

| Well-described methodology with sufficient sample size and comprehensive statistical analysis. | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Clear methodology, large sample size, valid measurement tools, and proper statistical analysis conducted. | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Small sample size, clearly described methods, and possible risk of self-reporting bias present. | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| Small sample size and unelaborated methodology. | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Sufficient data, inappropriate data analysis, and unclear reporting methodology. | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total Studies | 12 | 2 | 0 |

| First Author | Study Design | Aim | Country | Topic | Age |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ewelina Chawłowska et al., 2020 [38] | Cross-sectional study | Assessing student’s knowledge related to fertility physiology and fertility patterns | Poland | Reproductive health literacy and fertility awareness | 21.95 ± 2.45 |

| Eusebius Small et al., 2023 [39] | Cross-sectional study | Assessing the relationship between sexual health literacy, parental education, and risky sexual behaviour | Sierra Leon | Sexual health literacy, parental education, and risky sexual behaviour | 24.3 ± 5.63 |

| Aslantekin-Özcoban F, Gün M 2021 [40] | Cross-sectional study | Assessing university student knowledge on emergency contraception, influencing factors and e-health literacy levels | Turkey | Emergency contraception knowledge level and e-health literacy | |

| Mereerat Manwong 2022 [41] | Mixed methods study | Investigating factors associated with SHL and preventive behaviours | Thailand | Sexual health literacy and preventive behaviours | |

| Amy E. Albright, Rebecca S. Allen 2018 [42] | Cross-sectional study | Assessing HPV knowledge and awareness | USA | HPV misconceptions and the role of health literacy | |

| Ashley Sons and Ann L. Eckhardt, 2023 [23] | Cross-sectional study | Examining health literacy and knowledge of female reproduction, contraception, and sexually transmitted infections (STIs) | USA | Health literacy and knowledge of female reproduction in undergraduate students | 19.9 ± 1.2 |

| Derick Akompab Akoku et al., 2022 [43] | Cross-sectional study | Examining the association between fertility awareness knowledge, and contraceptive use | Cameroon | Childbearing intentions, fertility awareness knowledge, and contraceptive use | 23 years (IQR = 21–25) |

| Cheryl A. Vamos, 2020 [27] | Focus Group Discussion | Assessing college students’ sexual and reproductive health (SRH) literacy experiences, specifically contraception use and STI prevention | USA | Exploring college students’ sexual and reproductive health literacy | |

| Izzatul Arifah 2022 [44] | Cross-sectional study | Examining the relationship between health literacy and use of reproductive health counselling services among high school students | Indonesia | Health literacy and utilization of reproductive health services | |

| Rabia Sohbet Fatma Gec ici, 2014 [45] | Descriptive study | Examining the level of knowledge on sexuality and reproductive health (SRH) | Turkey | Examining the level of knowledge on sexuality and reproductive health | |

| Park A et al., 2017 [46] | Cross-sectional study | Assessing health literacy using three validated measures and examining cross-sectional and prospective associations between health literacy and adolescent health behaviours and outcomes | USA | Associations between health literacy and health behaviours | 14 years |

| Elif Şenocak Taşçı, MD et al., 2023 [47] | Cross-sectional study | Assessing university students’ knowledge of HPV and the association between HL and HPV vaccinations | Turkey | Assessment of health literacy and HPV knowledge | 21.98 ± 4.72 |

| Narkarat and Taneepanichskul MD 2021 [48] | Cross-sectional study | Assessing the level of SHL and exploring factors associated with SHL | Thailand | Factors associated with sexual health literacy | |

| Yağmur Sürmeli et al., 2024 [49] | Quasi-experimental | Evaluating the effect of sexual health education sexual myths and sexual health literacy in university students | Turkey | The effect of sexual health education on sexual myths and sexual health literacy | 19.8 ± 1.37 |

| Author | Sample Size | Outcome (Measure Type) | Variables of Adjusted Analysis | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ewelina Chawłowska et al., 2020 [38] | 456 women | Assess student’s knowledge fertility-related physiology and fertility patterns | Knowledge, age, year of study, university, sources of information | Health literacy is associated with different knowledge levels; higher levels were observed in women, people with higher education, those having difficult conceiving, and those who had planned their pregnancies |

| Eusebius Small et al., 2023 [39] | 338 university students | Relationship between sexual health literacy, parental education, and risky sexual behaviour | Family social economic status (SES), STI knowledge, sexual risk behaviour | Parental health literacy is significantly associated with student’s sexual risk behaviour |

| Aslantekin-Özcoban F, Gün M 2021 [40] | 1003 senior undergraduate students | Assess university student knowledge of emergency contraception, influencing factors, and e-health literacy levels | Knowledge of emergency contraception were significantly correlated positively with e-Health literacy; therefore, improving e-health literacy of students can be key to improving knowledge of emergency contraception | |

| Mereerat Manwong 2022 [41] | 730 students; 59.2% female and 40.8% male | Investigate factors associated with SHL and preventive behaviours among middle school students | Sex, nightlife, drinking alcohol beverages, sexual intercourse experience and sexual health literacy | Significant factors associated with preventive behaviours regarding pregnancy and STDs were sex, nightlife venue, drinking alcoholic beverages, sexual intercourse experience, and SHL. The most effective factor was SHL, which was the main concept integrated into the online program |

| Amy E. Albright, Rebecca S. Allen 2018 [42] | 360 students from South-Eastern University in the USA | Assess HPV knowledge and awareness in a sample of US college students | Health literacy was not related to vaccination status; it was associated with a greater knowledge of both HPV and available vaccines. The sociocultural aspect of health literacy was also found to significantly relate to HPV knowledge | |

| Ewelina Chawłowska et al., 2020 [38] | 456 women | Assess student’s knowledge of fertility-related physiology and fertility patterns | Knowledge, age, year of study, university, sources of information | Health literacy is associated with different knowledge levels, higher level in women, people of higher education, those having difficult conceiving, and those who had planned their pregnancies |

| Park A. et al., 2017 [46] | 250 adolescents | Assess health literacy using three validated measures and examine cross-sectional and prospective associations between health literacy and adolescent health behaviours and outcomes | Age, male, White ethnicity, free lunch program | Health literacy was associated with a lower self-rating of general health, unhealthier diet, heavier weight, and greater engagement in problem behaviours and sexual behaviours at baseline. Lower baseline health literacy also was associated with a greater increase in substance use over time |

| Elif Şenocak Taşçı, MD et al., 2023 [47] | 361 university students | Assess the university students’ knowledge about HPV and the association between HL and HPV vaccination | General HPV knowledge level was significantly better among women and those with a family history of cancer and was significantly lower among students in their prep or first year of school. Higher levels of HPV knowledge and total HPV-KS score were statistically significantly higher in students with adequate/excellent HL | |

| Narkarat and Taneepanichskul MD 2021 [48] | 128 females secondary school students | Assess the level of SHL and to explore factors associated with SHL | The results showed that the grade point average (GPA) was statistically significantly associated with SHL | |

| Yağmur Sürmeli et al., 2024 [49] | 51 students; 84.3% female, 15.7% male | Evaluate the effect of sexual health education on university students’ understanding of sexual myths and sexual health literacy | Increased knowledge after training |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Prémusz, V.; Mesfin, M.D.; Atmaca, L.; Chauhan, S.; Tándor, Z.; Bodor, L.A.; Várnagy, Á.; Galgalo, D.A. Exploring the Impact of Health Literacy on Fertility Awareness and Reproductive Health in University Students—A Systematic Review. Healthcare 2025, 13, 2342. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13182342

Prémusz V, Mesfin MD, Atmaca L, Chauhan S, Tándor Z, Bodor LA, Várnagy Á, Galgalo DA. Exploring the Impact of Health Literacy on Fertility Awareness and Reproductive Health in University Students—A Systematic Review. Healthcare. 2025; 13(18):2342. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13182342

Chicago/Turabian StylePrémusz, Viktória, Melese Dereje Mesfin, Leman Atmaca, Shalini Chauhan, Zoltán Tándor, Lili Andrea Bodor, Ákos Várnagy, and Dahabo Adi Galgalo. 2025. "Exploring the Impact of Health Literacy on Fertility Awareness and Reproductive Health in University Students—A Systematic Review" Healthcare 13, no. 18: 2342. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13182342

APA StylePrémusz, V., Mesfin, M. D., Atmaca, L., Chauhan, S., Tándor, Z., Bodor, L. A., Várnagy, Á., & Galgalo, D. A. (2025). Exploring the Impact of Health Literacy on Fertility Awareness and Reproductive Health in University Students—A Systematic Review. Healthcare, 13(18), 2342. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13182342