Nutrition for Children with Down Syndrome—Current Knowledge, Challenges, and Clinical Recommendations—A Narrative Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

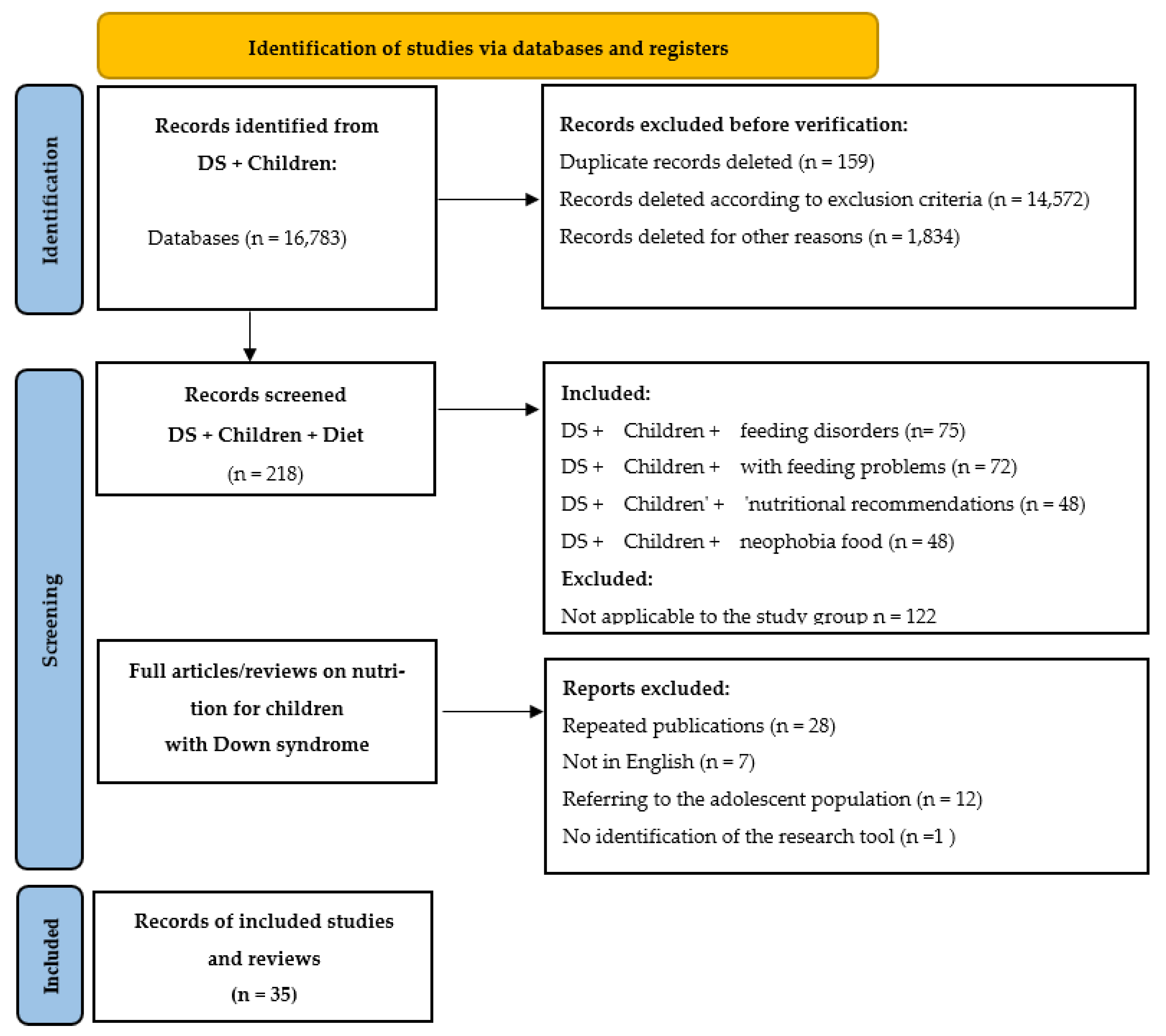

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Data Synthesis

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the Nutritional Needs of Children with Down Syndrome

3.1.1. Reduced Energy Requirements in Children with Down Syndrome

3.1.2. Body Composition of Children with Down Syndrome

3.1.3. Comorbidities and Nutritional Needs of Children with Down Syndrome

- Hypothyroidism—estimated to occur in over 15% of children with Down syndrome, it affects the metabolic rate and may increase weight gain [4]. It requires strict control of the energy content of the diet and the intake of iodine, selenium, and iron.

- Celiac disease—diagnosed in 4.6–7.1% of children with DS [4,12,13]. If coexisting, a gluten-free diet is necessary, as it is the only effective treatment for this condition. Due to the restriction of gluten-containing cereal products, an elimination diet may lead to deficiencies in dietary fiber, B vitamins (especially B1, B6, and folic acid), and iron, which justifies the need for monitoring and appropriate supplementation [24].

- Gastroenterological disorders are common clinical problems observed in children with Down syndrome. The most common disorders include gastroesophageal reflux and chronic constipation, which may be functional or result from coexisting anatomical anomalies of the gastrointestinal tract. Due to the diverse etiology of symptoms, an individual diagnostic and therapeutic approach is necessary in treatment [25].

- Immune system disorders, which are often observed in children with Down syndrome, predispose them to recurrent infections, which can lead to periodic loss of appetite and require temporary modification of the structure and nutritional value of the diet [26].

3.1.4. Physical Activity in Children with Down Syndrome

3.2. Nutritional Disorders Typical of Children with Down Syndrome

Sucking, Swallowing, and Biting Disorders

3.3. Selectivity and Food Neophobia

3.4. Delayed Development of Independent Eating

- Fine motor skills (hand and finger coordination). Studies indicate that children with DS demonstrate delays in motor development, which affect their ability to manipulate objects such as cutlery and cups. For example, analyses of motor test results have shown significant impairments in both fine and gross motor skills [18].

- Visual-motor perception. Virji-Babul et al. reported that children with DS have difficulties in recognizing biological motion, suggesting impaired processing of global movement patterns. These deficits may adversely affect visual-motor integration, which is crucial for activities such as independent eating. The authors highlight the importance of early interventions aimed at enhancing visual integration to support skill acquisition in this group [19].

- Motor planning (praxis). A study by Fidler and colleagues (2005) assessed praxis skills in young children with DS, children with other developmental disabilities, and typically developing peers. Findings demonstrated significant deficits in planning and executing purposeful, sequential motor actions among children with DS. Notably, difficulties were observed in tasks requiring gesture imitation and performance of movement commands based on verbal instructions. The authors emphasize that praxis impairments can substantially limit the acquisition and automation of complex everyday skills—such as eating, dressing, and hygiene—underscoring the need for early, targeted therapy to support functional development in this population [20].

3.5. Key Nutrients in the Diet of Children with Down Syndrome

3.5.1. Protein

3.5.2. Fats

3.5.3. Carbohydrates

3.6. Characteristics of Nutritional Challenges in Children with Down Syndrome

3.7. Diet Therapy Models and Current Guidelines

3.7.1. Recommendations of the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP):

- The most comprehensive document on the care of children with DS is the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) position statement “Health Supervision for Children and Adolescents With Down Syndrome” [3].

- Although the document does not include a dedicated chapter on nutritional recommendations, it addresses several aspects relevant from a clinical nutrition perspective. These include the following:

- growth monitoring using centile charts specifically developed for children with Down syndrome;

- regular assessment of biochemical parameters, including iron, ferritin, vitamin D, TSH, and glucose levels;

- promotion of physical activity and a healthy lifestyle;

- weight control and early nutritional intervention in cases of risk for overweight or malnutrition.

- The AAP also emphasizes the importance of an interdisciplinary approach and recommends ensuring access to a clinical dietitian for children with DS in cases of feeding disorders, gastrointestinal diseases, abnormal weight gain, or the need for an elimination diet [3]

3.7.2. ESPGHAN and EFAD Guidelines

- reducing energy intake in children with limited physical activity and delayed development, while increasing the nutritional density of the diet;

- monitoring growth and adjusting food consistency according to oromotor abilities;

- implementing nutritional interventions based on a comprehensive assessment of nutritional status, including laboratory tests and evaluation of eating habits;

- ensuring interdisciplinary care involving physicians, dietitians, feeding therapists, physiotherapists, and psychologists.

4. Summary and Practical Recommendations

4.1. Conclusions from the Literature Review

- Growth disorders and body composition abnormalities. Children with Down syndrome are typically characterized by shorter stature, higher body fat levels, and reduced lean body mass. Their basal metabolic rate (BMR) is significantly lower, which increases the risk of overweight and obesity, even with an apparently “normal” energy intake.

- High prevalence of comorbidities. Conditions such as hypothyroidism, celiac disease, constipation, gastroesophageal reflux, and immune disorders substantially affect nutrient tolerance and absorption, necessitating the continuous monitoring of nutritional status and biochemical parameters.

- Feeding difficulties and food selectivity. Delayed development of oromotor functions, limited acceptance of textures, sensory preferences, and challenges with eating independence are common and have a critical impact on diet quality. Without appropriate intervention, these issues may result in nutrient deficiencies and contribute to social isolation.

- Lack of official, dedicated guidelines. To date, no country has developed comprehensive dietary recommendations that take into account the specific needs of children with Down syndrome, including those related to feeding disorders. In clinical practice, general pediatric guidelines are typically applied and subsequently adapted to the particular requirements arising from developmental disabilities and comorbidities, with a regular assessment of individual patient needs. It should be emphasized that although some organizations (e.g., AAP, ESPGHAN) provide partial recommendations relevant to this population, they do not constitute dedicated, comprehensive nutritional guidelines for children with Down syndrome.

4.2. Practical Recommendations for Therapeutic Teams

4.2.1. Assessment and Monitoring of Nutritional Status

- Use dedicated centile charts for children with DS (e.g., growth charts for children with Down syndrome) (EBM).

- Measure height, weight, BMI, waist circumference, body composition (BIA), and skinfold thickness every 6–12 months (EBM).

- Conduct a nutritional interview, taking into account meal patterns, consistency, preferences, selectivity, and the presence of eating difficulties (EBM).

4.2.2. Diet

- Meals should be regular (4–5 per day), calorie-controlled (10–15% reduction from normal intake), and rich in nutrients (EBM).

- Include good sources of protein, healthy fats (including omega-3), and complex carbohydrates (EBM).

- Adjust the consistency to the child’s oral motor skills, but avoid prolonged use of purees or blended foods (EBM).

4.2.3. Nutritional Therapy to Support Independence

- Work with a speech therapist/neurological speech therapist and feeding therapist to improve oromotor function (EBM).

- Encourage your child to participate in meal preparation and make simple decisions (“What to eat?”) (CP).

- Use adaptive aids: spoons, forks, plates with rims, cups with handles (CP).

- Educate the family on positive modeling and eliminating pressure during mealtimes (CP).

4.2.4. Interdisciplinary Cooperation

- Set up a therapeutic team (doctor, clinical dietitian, speech therapist/neurological speech therapist, psychologist, physical therapist) and schedule regular meetings every 6 months (CP).

- Document progress, modify recommendations on an ongoing basis, and adapt them to the child’s changing needs (CP).

4.2.5. Future Needs—Research Perspective

- develop official population-based nutritional guidelines for children and adults with DS(CP).

- conduct randomized clinical trials on the effectiveness of dietary and supplementation interventions in this group (EBM),

- implement nationwide educational and preventive programs aimed at families, schools, and institutions supporting people with intellectual disabilities (CP).

4.3. Summary

4.4. Conclusions for the Future

- Need to develop dedicated nutritional guidelines. There is a clear gap in official, evidence-based dietary recommendations for children with Down syndrome. It is essential to establish expert working groups within national and international organizations (e.g., EFAD, ESPGHAN, PTD) to develop comprehensive, population-specific guidelines tailored to the unique needs of this group.

- Development of intervention studies. The vast majority of data on nutrition in children with DS are derived from observational research. There is an urgent need for randomized clinical trials to evaluate the effectiveness of specific dietary interventions—such as supplementation strategies, family education programs, and feeding therapy—in improving nutritional status, psychomotor development, and quality of life.

- Inclusion of nutrition in early intervention programs. Incorporating nutritional assessment and care into early intervention services, along with the inclusion of clinical dietitians in multidisciplinary developmental support teams, would enable the early identification and management of feeding disorders in infancy, which may be critical for preventing somatic and functional developmental abnormalities.

- Integration of nutritional care into healthcare and education systems. Developing and implementing structured dietary care models integrated into educational institutions, daycare facilities, and rehabilitation centers is crucial. Training for parents, teachers, and therapists should systematically include a nutritional component.

- Expansion of preventive and educational measures. In light of the increasing life expectancy and improved medical care of individuals with DS, it is necessary to implement nationwide nutritional prevention programs that encompass children, adolescents, and adults with Down syndrome.

5. Strengths and Limitations of the Review

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Weijerman, M.E.; De Winter, J.P. Clinical practice: The care of children with Down syndrome. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2010, 169, 1445–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bittles, A.H.; Glasson, E.J. Clinical, social, and ethical implications of changing life expectancy in Down syndrome. Dev. Med. Child. Neurol. 2004, 46, 282–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bull, M.J.; Trotter, T.; Santoro, S.L.; Christensen, C.; Grout, R.W. Health supervision for children and adolescents with Down syndrome. Pediatrics 2022, 149, e2022057010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roizen, N.J.; Patterson, D. Down’s syndrome. Lancet 2003, 361, 1281–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gruszka, J.; Włodarek, D. General dietary recommendations for people with Down syndrome. Nutrients 2024, 16, 2656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertapelli, F.; Pitetti, K.; Agiovlasitis, S.; Guerra-Junior, G. Overweight and obesity in children and adolescents with Down syndrome—Prevalence, determinants, consequences, and interventions: A literature review. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2016, 57, 181–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anil, M.A.; Shabnam, S.; Narayanan, S. Feeding and swallowing difficulties in children with Down syndrome. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2019, 63, 992–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xanthopoulos, M.S.; Walega, R.; Xiao, R.; Pipan, M.E.; Cochrane, C.I.B.; Zemel, B.S.; Kelly, A.M.; Magge, S.N.M. Physical activity in youth with DS and its relationship with adiposity. J. Dev. Behav. Pediatr. 2023, 44, E436–E443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Moher, D. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Białek-Dratwa, A. Dietetyka oparta na dowodach naukowych—Klasyfikacja diet. In Diety Alternatywne W Poradnictwie Żywieniowym; Białek-Dratwa, W.A., Grajek, M., Eds.; Wydawnictwo Śląskiego Uniwersytetu Medycznego w Katowicach: Katowice, Poland, 2022; pp. 11–20. [Google Scholar]

- Luke, A.; Sutton, M.; Schoeller, D.A.; Roizen, N.J.M. Nutrient intake and obesity in prepubescent children with Down syndrome. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 1996, 96, 1262–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carnicer JÂ, S.; Farre, C.; Varea, V.; Vilar, P.; Moreno, J.; Artigas, J. Prevalence of coeliac disease in Down’s syndrome. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2001, 13, 263–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Book, L.; Hart, A.; Black, J.; Feolo, M.; Zone, J.J.; Neuhausen, S.L. Prevalence and clinical characteristics of celiac disease in Downs syndrome in a U.S. study. Am. J. Med. Genet. 2001, 98, 70–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frazier, J.B.; Friedman, B. Swallow function in children with Down syndrome: A retrospective study. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 1996, 38, 695–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanley, M.A.; Shepherd, N.; Duvall, N.; Jenkinson, S.B.; Jalou, H.E.; Givan, D.C.; Steele, G.H.; Davis, C.; Bull, M.J.; Watkins, D.U.; et al. Clinical identification of feeding and swallowing disorders in 0–6 month old infants with Down syndrome. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part A 2019, 179, 230–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Białek-Dratwa, A.; Żur, S.; Sokal, A.; Staśkiewicz-Bartecka, W.; Kowalski, O. Feeding challenges in Trisomy 21: Prevalence and characteristics of feeding disorders and food neophobia—A cross-sectional study of Polish children and adolescents with Down syndrome. Nutrients 2025, 17, 2030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, C.F.; Bernhard, C.B.; Smith-Simpson, S. Parent-reported ease of eating foods of different textures in young children with Down syndrome. J. Texture Stud. 2019, 50, 426–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Connolly, B.H.; Michael, B.T. Performance of retarded children, with and without Down syndrome, on the Bruininks-Oseretsky Test of Motor Proficiency. Phys. Ther. 1986, 66, 344–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virji-Babul, N.; Kerns, K.; Zhou, E.; Kapur, A.; Shiffrar, M. Perceptual-motor deficits in children with Down syndrome: Implications for intervention. Down Syndr. Res. Pract. 2006, 10, 74–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fidler, D.J.; Hepburn, S.L.; Mankin, G.; Rogers, S.J. Praxis skills in young children with Down syndrome, other developmental disabilities, and typically developing children. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 2005, 59, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Białek-Dratwa, A.; Żur, S.; Wilemska-Kucharzewska, K.; Szczepańska, E.; Kowalski, O. Nutrition as prevention of diet-related diseases—A cross-sectional study among children and young adults with Down syndrome. Children 2023, 10, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González-Agüero, A.; Vicente-Rodríguez, G.; Moreno, L.A.; Guerra-Balic, M.; Ara, I.; Casajús, J.A. Health-related physical fitness in children and adolescents with DS and response to training. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2010, 20, 716–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zemel, B.S.; Pipan, M.; Stallings, V.A.; Hall, W.; Schadt, K.; Freedman, D.S.; Thorpe, P. Growth charts for children with DS in the United States. Pediatrics 2015, 136, e1204–e1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saturni, L.; Ferretti, G.; Bacchetti, T. The gluten-free diet: Safety and nutritional quality. Nutrients 2010, 2, 16–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, G. Gastrointestinal disorders in Down syndrome. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. Bed Bench 2014, 7, 5–8. [Google Scholar]

- Nespoli, L.; Burgio, G.R.; Ugazio, A.G.; Maccario, R. Immunological features of Down’s syndrome: A review. Ital. J. Pediatr. 1993, 19, 5–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. WHO Guidelines on Physical Activity and Sedentary Behaviour. 2020. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240015128 (accessed on 5 June 2025).

- Lewis, E.; Kritzinger, A. Parental experiences of feeding problems in their infants with Down syndrome. Down Sydrome Res. Pract. 2004, 9, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravel, A.; Mircher, C.; Rebillat, A.S.; Cieuta-Walti, C.; Megarbane, A. Feeding problems and gastrointestinal diseases in Down syndrome. Arch. Pédiatr. 2020, 27, 137–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faulks, D.; Collado, V.; Mazille, M.N.; Veyrune, J.L.; Hennequin, M. Masticatory dysfunction in persons with Down’s syndrome. Part 1: Aetiology and incidence. J. Oral Rehabil. 2008, 35, 854–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dovey, T.M.; Staples, P.A.; Gibson, E.L.; Halford, J.C.G. Food neophobia and ‘picky/fussy’ eating in children: A review. Appetite 2008, 50, 181–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopman, E.; Csizmadia, C.G.; Bastiani, W.F.; Engels, Q.M.; A DE Graaf, E.; LE Cessie, S.; Mearin, M. Eating habits of young children with DSin The Netherlands: Adequate nutrient intakes but delayed introduction of solid food. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 1998, 98, 739–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esposito, P.E.; MacDonald, M.; Hornyak, J.E.; Ulrich, D.A. Physical activity patterns of youth with Down syndrome. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 2012, 50, 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Baumer, N.; Augustyn, M. Hyperphagia and Down syndrome. J. Dev. Behav. Pediatr. 2023, 44, e444–e446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreau, M.; Benhaddou, S.; Dard, R.; Tolu, S.; Hamzé, R.; Vialard, F.; Movassat, J.; Janel, N. Metabolic diseases and Down syndrome: How are they linked together? Biomedicines 2021, 9, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordstrøm, M.; Retterstøl, K.; Hope, S.; Kolset, S.O. Nutritional challenges in children and adolescents with Down syndrome. Lancet Child Adolesc. Health 2020, 4, 455–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahidi, F.; Ambigaipalan, P. Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids and their health benefits. Annu. Rev. Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 9, 345–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kmiecik, D.; Szopa, M.; Kobus-Cisowska, J.; Przeor, M.; Jędrusek-Golińska, A.; Szymandera-Buszka, K. Słodycze jako źródło tłuszczu i nasyconych kwasów tłuszczowych w diecie. Bromatol. I Chem. Toksykol. 2016, 49, 302–307. [Google Scholar]

- Romano, C.; van Wynckel, M.; Hulst, J.; Broekaert, I.; Bronsky, J.; Dall’OGlio, L.; Mis, N.F.; Hojsak, I.; Orel, R.; Papadopoulou, A.; et al. European Society for Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition guidelines for the evaluation and treatment of gastrointestinal and nutritional complications in children with neurological impairment. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2017, 65, 242–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Element | Detailed Description | Example Wording |

|---|---|---|

| P (Population) | Children and adolescents with DS (aged 0–18), regardless of gender, degree of intellectual disability or comorbidities. | Children and adolescents aged 0–18 years diagnosed with DS (Trisomy 21). |

| I (Intervention) | All dietary and nutritional interventions, such as individual diet therapy, nutrition education for parents, supplementation (e.g., DHA, vitamin D), modification of food texture, elimination diets (e.g., gluten-free), and programs to support independent eating. | Nutritional interventions including dietary counseling, food texture modification, supplementation, or elimination diets. |

| C (Comparison) | No intervention or standard dietary management used in children without Down syndrome; possibly comparison of different dietary strategies (e.g., intervention A vs. B). | Standard dietary care or no nutritional intervention. |

| O (Outcomes) | Changes in nutritional status (body weight, BMI, body composition), eating behaviors (food selectivity, independence), oromotor functions, quality of life, reduction in dietary errors. | Improvement in nutritional status, reduction in obesity risk, increased dietary diversity, improved self-feeding abilities. |

| Author, Year | Research Group (n, Age) | Research Objective/Area | Tools/Methods Used | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anil, M.A., Shabnam, S., & Narayanan, S. (2019). [7] | 17 children with DS (10 girls and 7 boys) and 47 typically developing children (20 girls and 27 boys). | Assessment of possible feeding and swallowing problems in children with DS aged 2–7 years | • Questionnaire for assessing feeding problems in children with DS (developed and validated) • Com-DEALL Checklist (assessment of oromotor skills) • Feeding Handicap Index for Children—FHI-C (assessment of the impact of problems) • Video recordings of feeding sessions • Direct observation of feeding with different foods | • Children with DS are more likely to have feeding problems—mainly with food consistency, swallowing and control in the mouth. • Reduced oromotor abilities—weaker movements of the jaw, tongue and lips compared to the control group. • Greater burden on families—parents reported significantly more difficulties in all domains (physical, functional, emotional). |

| Xanthopoulos, M.S., Walega, R., Xiao, R., Pipan, M.E., Cochrane, C.I., Zemel, B.S., Kelly, A., & Magge, S.N. (2022) [8] | 77 young people with DS (aged 10–20; and 57 people without DS, matched for age, gender, race, ethnicity and BMI | Assessment of physical activity levels and their association with visceral adiposity (VFAT) in adolescents with Down syndrome | • Sense Wear Mini accelerometer—7-day activity recording (min/day LPA, MVPA, SA, steps) • Anthropometry (BMI-Z, height, weight) • Body composition—DXA (visceral fat, VFAT) • Assessment of puberty according to stages | • Adolescents with DS took fewer steps/day and performed less MVPA (trend), but spent more time in LPA. • 63% of DS met the recommendations of ≥60 min MVPA/day (no difference vs. control group). • LPA inversely and SA positively correlated with BMI-Z and VFAT. • MVPA was negatively associated with BMI-Z and VFAT, especially in boys. |

| Luke, A., Sutton, M., Schoeller, D.A., Roizen, N.J.M. (1996) [11] | 10 children with DS (aged 5–11) and 10 healthy children | Assessment of body composition, energy expenditure, and energy and nutrient intake in children with DS compared to a control group | • Deuterium dilution (TBW, FFM) • Electrical bioimpedance (BIA) • Skin fold measurement (4-point) • Double-labeled water (energy expenditure) • 3-day food intake records (1 weekend day, 2 weekdays) • Food Processor II diet analysis | • 50% of children with DS met the criteria for obesity (weight/height index > 1.2). • No differences in body composition were found between the groups (FFM, FM). • Energy intake was significantly lower in the DS group in relation to the RDA. • Lower intake of riboflavin, vitamin B6, iron, and calcium in DS vs. control. • 50% of children with DS had Ca/Zn deficiencies; 80% had low copper intake. |

| Carnicer, J., Farre, C., Varea, V., Vilar, P., Moreno, J., Artigas, J. (2001) [12] | 284 people with DS (aged 1–25), Spain | Assessment of the prevalence of coeliac disease in individuals with DS | • Determination of AGA (anti-gliadin) and AEA (anti-endomysial) antibodies in the IgA/IgG class • In positive or symptomatic cases—small intestine biopsy | • Coeliac disease confirmed in 18 people (6.3%). • 94% of patients were AEA positive, 78% were AGA positive. • 15/18 patients had clinical symptoms (mainly intestinal), 3 cases were asymptomatic. • The authors recommend routine screening for coeliac disease in children and adolescents with DS. |

| Book, L., Hart, A., Black, J., Feolo, M., Zone, J.J., Neuhausen, S.L. (2001) [13] | 97 children with DS (USA), Caucasian, age not specified (1–18 years) | Assessment of the prevalence and clinical characteristics of coeliac disease in children with DS in the USA | • Serological tests: IgA EMA antibodies • HLA DQA1/DQB1 genotyping • Clinical evaluation (intestinal symptoms, growth) • Analysis of first-degree relatives | • 10.3% of children with DS were EMA positive (probable coeliac disease). • Clinical symptoms were non-specific; only flatulence was more common in EMA+. • 88% of EMA+ children had a high risk of the HLA DQA10501 DQB10201 haplotype. • 10% of first-degree relatives of EMA+ children, also had EMA+. • The authors recommend routine screening for coeliac disease in children with DS. |

| Frazier, J.B., Friedman, B. (1996) [14] | 19 children with DS (retrospective study) | Assessment of swallowing function and aspiration risk in children with DS | • Retrospective analysis of feeding behavior • Assessment of swallowing phases (oral, pharyngeal) • Observation of aspiration symptoms (coughing, choking) | • Pharyngeal phase disorders were found in 16/19 children. • Aspiration occurred in 10 children, often in the form of “silent aspiration” (asymptomatic). • Oral hypersensitivity made it difficult to accept foods with a specific texture. • Aspiration was considered a significant risk factor for respiratory diseases in children with DS. |

| Stanley, M.A., Shepherd, N., Duvall, N., Jenkinson, S.B., Jalou, H.E., Givan, D.C., … Roper, R.J. (2019) [15] | 174 infants with Down syndrome, aged 0–6 months. | Assessment of the prevalence of feeding and swallowing disorders and risk factors for dysphagia in the youngest children with DS | • Retrospective analysis of medical records • Clinical assessment of feeding and swallowing problems • Videofluoroscopic Swallow Study (VFSS) • Analysis of risk factors (CHD, prematurity, low birth weight, desaturation, respiratory abnormalities) | • Dysphagia (oral and/or pharyngeal) was found in 55% of infants, and 39% required thickening of food or parenteral nutrition. • Highest risk of dysphagia: desaturation during feeding (OR = 15.8), respiratory abnormalities (OR = 7.2). • Prematurity and low birth weight increased the risk of dysphagia; severe heart defects were not significantly associated. |

| Białek-Dratwa, A., Żur, S., Sokal, A., Staśkiewicz-Bartecka, W., Kowalski, O. (2025) [16] | 310 children, adolescents and young adults with DS in Poland (4 months–25 years) | Assessment of feeding difficulties and food neophobia and their associations with age, gender, and body weight | • CAWI survey (parents/guardians) • Montreal Children’s Hospital Feeding Scale (MCH-FS) • Food Neophobia Scale for Children (FNSC) • BMI analysis according to centile charts for DS • KomPAN—frequency questionnaire | • 26.5% had moderate to very severe feeding difficulties. • 41.3% showed high levels of food neophobia (most commonly in preschool age). • Neophobia and feeding difficulties were significantly correlated with age, but not with gender or body weight. • Children with high neophobia were less likely to consume vegetables, fish, legumes, nuts, wholemeal bread and red meat. |

| Ross, C.F., Bernhard, C.B., Smith-Simpson, S. (2019) [17] | 157 children with DS (various ages; parental reports) | Assessment of the ease and difficulty of eating foods with different textures as perceived by parents | • Open questionnaire (parents indicated easy/difficult textures) • Qualitative analysis—categorization into 26 texture groups | • Most difficult textures: chewy, hard. • Easiest textures: creamy, crispy, soluble, mushy, pureed, smooth, soft. • With age, “easy” textures became crispy/dry/hard, and “difficult” textures became juicy. • The results emphasize the need to gradually expand the acceptance of textures in children with DS. |

| Connolly, B.H., Michael, B.T. (1986) [18] | 24 children with intellectual disabilities: 12 with Down syndrome, 12 without DS; age 7.6–11 years (comparable mental age) | Assessment of motor skills (gross and fine) | Bruininks–Oseretsky Test of Motor Proficiency | • Children with DS scored lower than the control group in the following areas: running speed, balance, strength, and visual-motor control. • Girls with DS performed particularly poorly in strength, speed, manual dexterity and visual-motor coordination. • Both the composite scores for gross motor skills and fine motor skills were significantly worse in the DS group. |

| Virji-Babul, N., Kerns, K., Zhou, E., Kapur, A., Shiffrar, M. (2006) [19] | 12 children with DS (8–15 years; adaptive age 3–7 years) vs. 12 TD (4–8 years) | Assessment of perceptual-motor abilities (motion recognition) | Tasks requiring differentiation of increasingly complex visual-motor cues | • Children with DS were able to recognize simple movement cues but had significant deficits in the perception of complex visual-motor cues. • Perceptual-motor deficits may hinder the development of motor skills and independence. • Conclusions: interventions should focus not only on “milestones” but also on improving the integration of perception and movement. |

| Fidler, Hepburn, Mankin, Rogers (2005) [20] | 16 children with DS (mean age 33 months), 16 children with other developmental disabilities (matched age), 19 typically developing children | Assessment of motor skills and praxia in young children with DS and their relationship to adaptive functioning | Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales, Mullen Scales of Early Learning, praxia task battery, object retrieval task | • Children with DS had significantly lower motor and praxia scores than the group with other developmental disabilities. • Specific praxia deficits were found (problems with hand and whole-body coordination, ineffective reaching strategies). • Praxia deficits correlated with daily functioning (Vineland Daily Living Skills). • Children with DS more often asked for help with tasks, indicating different compensatory strategies. |

| Białek-Dratwa A., Żur S., Wilemska-Kucharzewska K., Szczepańska E., Kowalski O. (2022). [21] | 195 parents/caregivers of children, adolescents and young adults with DS (aged 0.5–30 years; median age 4.5 years; 32% of nursery age, 33% of preschool age, 12% of school age, 18% of teenage age, 4% of adult age) | Assessment of eating habits and potential dietary mistakes made by parents/caregivers | The study was conducted using the CAWI method with a validated questionnaire (30 questions) covering demographic data, comorbidities, feeding methods and eating habits of children with Down syndrome. | • Nutritional status: 21% underweight, 15.3% overweight, 5.6% obese. • Comorbidities: 52.3% hypothyroidism, 9.7% lactose intolerance, 3.6% coeliac disease, 3.6% Hashimoto’s disease. • Dietary eliminations: 62.6% no eliminations, 26.2% gluten elimination, 28.7% lactose elimination, 13.3% sucrose elimination, 8.7% casein elimination. • Early nutrition: 67.2% of children were breastfed, most often for 7–12 months. • Eating habits: vegetables and fruit—most often once a day (42.6% and 44.6%, respectively); dairy products—daily 36.9%, but 20% did not consume them at all; meat |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Żur, S.; Sokal, A.; Staśkiewicz-Bartecka, W.; Kiciak, A.; Grajek, M.; Krupa-Kotara, K.; Kowalski, O.; Białek-Dratwa, A. Nutrition for Children with Down Syndrome—Current Knowledge, Challenges, and Clinical Recommendations—A Narrative Review. Healthcare 2025, 13, 2222. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13172222

Żur S, Sokal A, Staśkiewicz-Bartecka W, Kiciak A, Grajek M, Krupa-Kotara K, Kowalski O, Białek-Dratwa A. Nutrition for Children with Down Syndrome—Current Knowledge, Challenges, and Clinical Recommendations—A Narrative Review. Healthcare. 2025; 13(17):2222. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13172222

Chicago/Turabian StyleŻur, Sebastian, Adam Sokal, Wiktoria Staśkiewicz-Bartecka, Agata Kiciak, Mateusz Grajek, Karolina Krupa-Kotara, Oskar Kowalski, and Agnieszka Białek-Dratwa. 2025. "Nutrition for Children with Down Syndrome—Current Knowledge, Challenges, and Clinical Recommendations—A Narrative Review" Healthcare 13, no. 17: 2222. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13172222

APA StyleŻur, S., Sokal, A., Staśkiewicz-Bartecka, W., Kiciak, A., Grajek, M., Krupa-Kotara, K., Kowalski, O., & Białek-Dratwa, A. (2025). Nutrition for Children with Down Syndrome—Current Knowledge, Challenges, and Clinical Recommendations—A Narrative Review. Healthcare, 13(17), 2222. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13172222