Problematic Social Media Use and Its Relationship with Breastfeeding Behaviors and Anxiety in Social Media-Native Mothers: A Mixed-Methods Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Method

2.1. Participants

2.2. Hypothesis

2.3. Ethical Considerations

2.4. Data Collection Procedure

- In what ways has social media influenced your sense of self-efficacy or confidence in caring for and feeding your baby?

- Can you describe if and how using social media has increased your feelings of anxiety, especially regarding your role as a mother?

- Have you experienced any negative outcomes or consequences from problematic or excessive social media use during the postpartum period? Could you describe them?

- Can you share a time when social media content affected your breastfeeding practices, either positively or negatively?

- Do you believe that problematic social media use has influenced your emotional well-being or your relationship with your baby? How?

- What do you think are the biggest challenges or risks associated with using social media as a new mother, especially when it comes to feeding practices and emotional health?

2.5. Quantitative Data Analysis

2.6. Qualitative Data Analysis

3. Findings

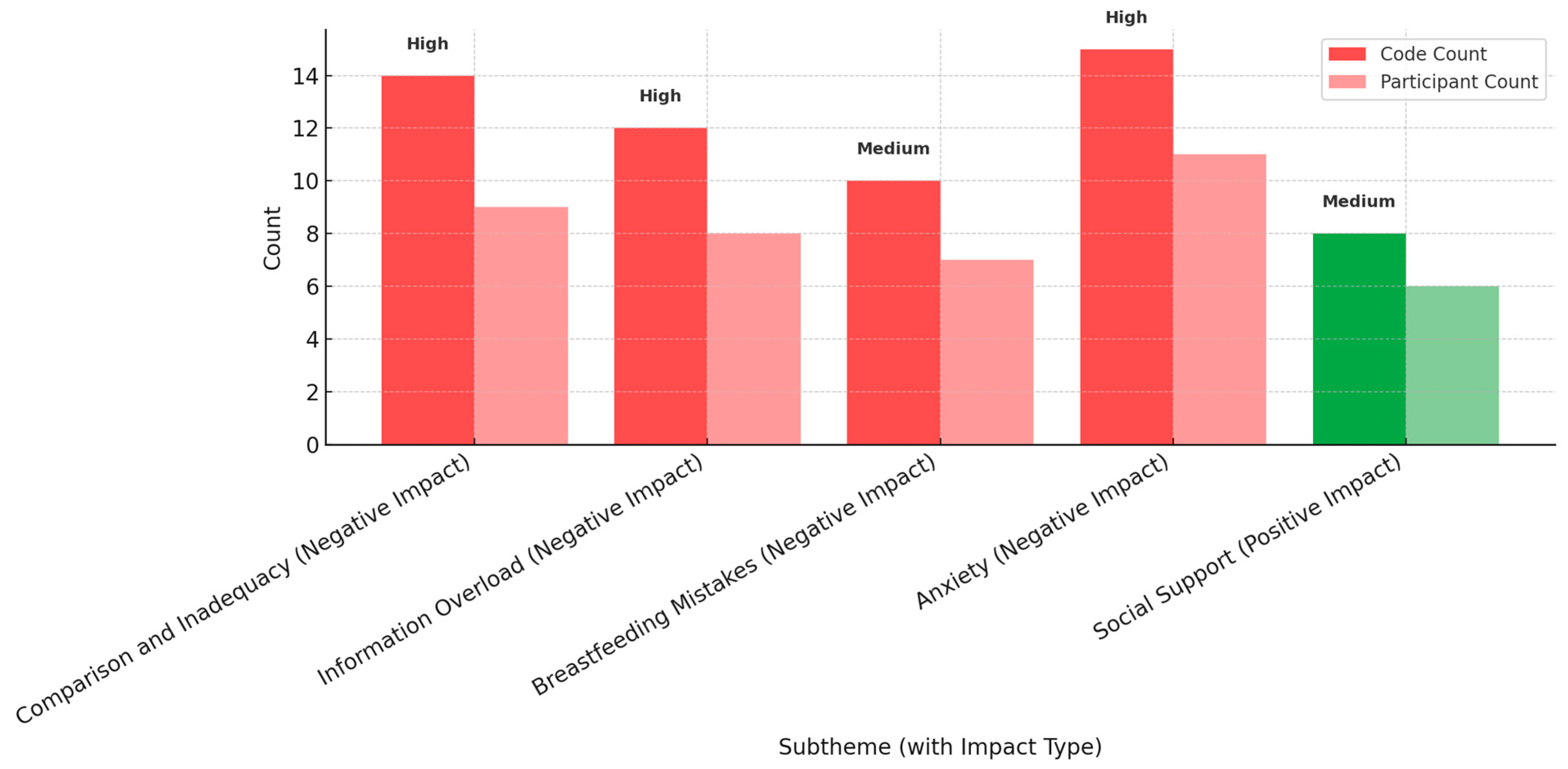

Qualitative Findings

4. Discussion

“When I see on Instagram that other mothers take perfect care of their babies and also manage the house beautifully, I feel inadequate, and my stress rises. No matter how well I do, it still feels like I’m falling short.”(Yasemin, age 24)

“Seeing that others on social media introduced complementary foods to their babies at an early age influenced me… I thought this might be a convenience, and my sleep would not be interrupted. I introduced complementary foods at the fourth month, and my baby experienced severe gas problems. Nothing changed for me, I was sleepless again and my baby’s stomach aches made me feel guilty”(Halime, 31 years)

“I’m tired of criticizing myself… Because influencer moms are always perfect. Our conditions are not equal, I know they exaggerated, but still, my self-confidence decreases.”(Pelin, 34 years)

“I stay up very late, and the next day I feel tired and less tolerant toward my baby. Sometimes I let the baby cry too much, I cannot get up, and then I feel guilty.”(Aylin, age 30)

“…when I spend time browsing the internet, I can’t eat properly, and it feels like my milk supply decreases.”(Yeliz, age 25)

“I told a blogger that I felt my milk supply was low, and she told me it was because my breasts were small. How frustrating! She kept pushing me to eat more and more.”(Ayşe, age 28)

“The marketed formula and milk-boosting products appeal to me. Sometimes I want to switch to formula so that the baby feels full and sleeps longer.”(Asiye, age 23)

“Thanks to the videos of a breastfeeding consultant on Instagram, I corrected my baby’s latch. It used to hurt a lot, and I was thinking about quitting.”(Buse, age 27)

“From a baby care website, I learned how to take care of myself as well. That was important and made me feel so much more at ease.”(Ceyda, age 22)

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Howe, N.; Strauss, W. The next 20 years: How customer and workforce attitudes will evolve. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2007, 85, 41–52. [Google Scholar]

- Hafızoğlu, Y. Z kuşağı seçmen davranışları. J. Educ. New Approaches 2021, 4, 141–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reer, F.; Festl, R.; Quandt, T. Investigating problematic social media and game use in a nationally representative sample of adolescents and younger adults. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2021, 40, 776–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazard, L. Digital mothering: Sharenting, family selfies and online affective-discursive practices. Fem. Psychol. 2022, 32, 540–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Infant and Young Child Feeding. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/infant-and-young-child-feeding (accessed on 27 July 2025).

- Lupton, D. The use and value of digital media for information about pregnancy and early motherhood: A focus group study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2016, 16, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, M.; Kaushal, D.; Joshi, S. Adverse Effect of social media on generation z user’s behavior: Government information support as a moderating variable. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2023, 72, 103256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montag, C.; Lachmann, B.; Herrlich, M.; Zweig, K. Digital phenotyping in psychological research: A systematic review of smartphone usage and mental health. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2019, 96, 289–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, L.S.; Valentini, J.P.; Monteiro, T.H.; Costacurta, M.C.D.F.; Soares, L.O.N.; Telfar-Barnard, L.; Nunes, P.V. problematic social media use and ıts relationship with depression or anxiety: A systematic review. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2022, 25, 691–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, J.; Moreland, J.J. The dark side of social networking sites: An exploration of the relational and psychological stressors associated with facebook use and affordances. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2015, 45, 168–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreassen, C.S.; Pallesen, S.; Griffiths, M.D. The relationship between addictive use of social media, narcissism, and self-esteem: Findings from a large national survey. Addict. Behav. 2017, 64, 287–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marino, C.; Gini, G.; Vieno, A.; Spada, M.M. The associations between problematic Facebook use, psychological distress, and well-being among adolescents and young adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2018, 226, 274–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandura, A. social cognitive theory: An agentic perspective. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2001, 52, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kardefelt-Winther, D. A conceptual and methodological critique of internet addiction research: Towards a model of compensatory internet use. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014, 31, 351–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Eijnden, R.J.; Lemmens, J.S.; Valkenburg, P.M. The social media disorder scale. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 61, 478–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muskens, L.; Hulsbosch, L.P.; van den Heuvel, M.I.; Croes, E.A.; Kop, W.J.; Pop, V.J.; Boekhorst, M.G. Social media use as a risk factor for depressive symptoms during pregnancy. J. Affect. Disord. 2023, 338, 495–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinman, S.A.; Edwards, C.B.; Snider, M.D.; Tolin, D.F.; Björgvinsson, T. Preventing postpartum anxiety and obsessive-compulsive disorder over the internet: An open-trial pilot study. Behav. Ther. 2025, 56, 192–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özen, Ç.İ.; Özkaya, B.E. Digital motherhood in the postpartum period: A descriptive study. Matern. Child Health J. 2025, 29, 376–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Human agency in social cognitive theory. Am. Psychol. 1989, 44, 1175–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumeister, R.F.; Heatherton, T.F. Self-regulation failure: An overview. Psychol. Inq. 1997, 1, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, E.T. Self-discrepancy: A theory relating self and affect. Psychol. Rev. 1987, 94, 319–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Festinger, L. A theory of social comparison processes. Hum. Relat. 1954, 7, 117–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball-Rokeach, S.J.; De Fleur, M.L.A. Dependency Model of Mass-Media Effects. Commun. Res. 1976, 3, 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, E.M. Diffusion of Innovations, 5th ed.; Free Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2003; Available online: https://books.google.com.tr/books?id=9U1K5LjUOwEC (accessed on 27 July 2025).

- Douglas, S.J.; Michaels, M.W. The Mommy Myth: The Idealization of Motherhood and How It Has Undermined All Women; Free Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- DeGroot, J.M.; Vik, T.A. Fake Smile. Everything is under control: The flawless performance of motherhood. West. J. Commun. 2021, 85, 42–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padoa, T.; Berle, D.; Roberts, L. Comparative social media use and the mental health of mothers with high levels of perfectionism. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 2018, 37, 514–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aker, S.; Kartal, Y.A.; Bulut, A.; Hızlıol, B. The ıdentity of motherhood transformed by social media: A phenomenological study. Ebelik Sağlık Bilim. Derg. 2024, 7, 478–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skelton, K.; Evans, R.; LaChenaye, J.; Amsbary, J.; Wingate, M.; Talbott, L. Exploring social media group use among breastfeeding mothers: Qualitative analysis. JMIR Pediatr. Parent. 2018, 1, e11344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, C.; Hashimoto, Y.; Nakatani, Y.; Ohira, M. Smartphone use during breastfeeding and ıts ımpact on mother–infant interaction and maternal responsiveness: Within subject design. Nurs. Health Sci. 2022, 24, 224–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asiodu, I.; Waters, C.; Dailey, D.; Lee, K.; Lyndon, A. Breastfeeding and use of social media among first-time african american mothers. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Neonatal Nurs. 2015, 44, 268–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bridges, N.; Howell, G.; Schmied, V. Exploring breastfeeding support on social media. Int. Breastfeed. J. 2018, 13, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, A.; Rance, J.; Warren, L. Body ımage concerns are associated with a shorter breastfeeding duration. Midwifery 2015, 31, 80–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkpatrick, C.E.; Lee, S. Comparisons to picture-perfect motherhood: How Instagram’s ıdealized portrayals of motherhood affect new mothers’ well-being. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2022, 137, 107417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, L.; Tiggemann, M.; Haines, J. #Fitmom: An experimental investigation of the effect of social media on body dissatisfaction and eating and physical activity intentions, attitudes, and behaviours among postpartum mothers. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2022, 22, 766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doner, Ş.İ.; Uçtu, A.K. Effect of formula milk advertisements published on social media on breastfeeding: Review article. Anatol. J. Ment. Health 2024, 1, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W.; Clark, V.L.P. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research; Sage Publishing: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kütahya City Hospital Mother-Baby Friendship Programme. Available online: https://kutahyasehir.saglik.gov.tr/TR-1084581/anne-dostu-ve-bebek-dostu.html (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Buchner, A.; Lang, A.G. Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behav. Res. Methods 2009, 41, 1149–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W.; Poth, C.N. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches; Sage Publishing: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Nommsen-Rivers, L.A.; Dewey, K.G. Development and validation of the infant feeding intentions scale. Matern. Child Health J. 2009, 13, 334–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Er, G.S.; Karayağız Muslu, G.; Güner, Ö. The Turkish Version of the Infant Feeding Intention Instrument (IFI-T). J. Clin. Pract. Res. 2019, 41, 269. [Google Scholar]

- De La Mora, A.; Russell, D.W. The Iowa infant feeding attitude scale: Analysis of reliability and validity. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 1999, 29, 2362–2380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eksioğlu, A.; Yeşil, Y.; Çeber Turfan, E. The translation and validation of the Iowa infant feeding attitude scale into Turkish. J. Educ. Res. Nurs. 2016, 13, 209–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarıçam, H.; Karduz, F.F.A. Sosyal medya kullanım bozukluğu ölçeği’nin Türk kültürüne uyarlanması: Geçerlik ve güvenirlik çalışması. J. Meas. Eval. Educ. Psychol. 2018, 9, 116–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spielberger, C.D.; Gorsuch, R.L.; Lushene, R.E. Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory; Consulting Psychologists Press: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Öner, N.; LeCompte, W.A. Durumluk-Sürekli Kaygı Envanteri El Kitabı; Boğaziçi Üniversitesi Yayınları: Istanbul, Turkey, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava, K.; Norman, A.; Ferrario, H.; Mason, E.; Mortimer, S. A qualitative exploration of the media’s influence on UK Women’s Views of Breastfeeding. Br. J. Midwifery 2022, 30, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alianmoghaddam, N.; Phibbs, S.; Benn, C. “I did a lot of Googling”: A qualitative study of exclusive breastfeeding support through social media. Women Birth 2019, 32, 147–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orchard, L.J.; Nicholls, W. A Systematic Review exploring the ımpact of social media on breastfeeding practices. Curr. Psychol. 2022, 41, 6107–6123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, E.M.; Riccabona, T.M.; Ventura, A.K. Technoference in infant feeding: The ımpact of maternal digital media use during breastfeeding on maternal attention and mother–infant interactions. Front. Dev. Psychol. 2024, 2, 1441486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morley-Hewitt, A.G.; Owen, A.L. A systematic review examining the association between female body image and the intention, initiation and duration of post-partum infant feeding methods (breastfeeding vs bottle-feeding). J. Health Psychol. 2019, 25, 207–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yiğitalp, G.; Bayram Değer, V.; Çifçi, S. Health literacy, health perception and related factors among different ethnic groups: A cross-sectional study in southeastern Turkey. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pazarcıkcı, F.; Ağralı, H.; Aydınlı, A. Annelerin Dijital Ebeveynlik Farkındalığının Sağlık Okuryazarlığı ve Çeşitli Değişkenler ile İlişkisi. Bağımlılık Derg. 2022, 23, 292–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Republic of Turkey, Ministry of Health, General Directorate of Public Health Child and Adolescent Health Department, Breastfeeding Promotion and Baby-Friendly Healthcare Institutions Program. Available online: https://hsgm.saglik.gov.tr/tr/programlar/beslenme-programlari?format=html (accessed on 27 August 2025).

- Huang, R.; Wan, Y.; Yao, X.; Wang, H.; Cai, C.T.; Xu, Y.T.; Jiang, H. Predictive factors of exclusive breastfeeding attrition at week 6 postpartum among mothers of preterm infants based on the theory of planned behaviour. Matern. Child Nutr. 2023, 19, e13470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Barwani, S.; Hodges, E.A.; Thoyre, S.M.; Knafl, K.A.; Crandell, J.L.; Sullivan, C. Cross-cultural adaptation and linguistic validation of the translated arabic revised breastfeeding attrition prediction tool. J. Nurs. Meas. 2023, 31, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gökşen, D.F.Y.; Özkan, S. The effect of online breastfeeding education on breastfeeding motivation: A randomized controlled study. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2024, 75, e42–e48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckland, C.; Hector, D.; Kolt, G.S.; Thepsourinthone, J.; Arora, A. Experiences of young australian mothers with infant feeding. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2022, 22, 489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cole, J.; Bhatt, A.; Chapple, A.G.; Buzhardt, S.; Sutton, E.F. Attitudes and barriers to breastfeeding among women at high-risk for not breastfeeding: A prospective observational study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2024, 24, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chekol Abebe, E.; Ayalew Tiruneh, G.; Asmare Adela, G.; Mengie Ayele, T.; Tilahun Muche, Z.; Behaile, T.; Mariam, A.; Asmamaw Dejenie, T. Levels and determinants of prenatal breastfeeding knowledge, attitude, and intention among pregnant women: A cross-sectional study in Northwest Ethiopia. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 920355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eskici, G.; Karahan, Y.S. Attitudes and practice of turkish mothers with babies between 0–24 months regarding infant nutrition: The ıowa infant feeding attitude scale. Rev. Nutr. 2022, 35, e210097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Z. Exploring the effect of social media on post-partum depression. Lect. Notes Educ. Psychol. Public Media 2023, 29, 75–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardelia, V.; Jaro’ah, S. Exploring social media use integration based on educational level among emerging adults. Int. J. Curr. Educ. Res. 2023, 2, 106–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu-Zarzuela, J.; Munoz, I.; Truong, N.; Zahra, A.; Mallya, M.; Grayson, K. Postpartum depression and facebook: A cross-sectional study of content quality and reliability. J. Affect. Disord. Rep. 2024, 16, 100745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia-Yuan, Z.; Hui, Z.; Yubin, C.; Ling-Hui, Z.; Yuqiu, Z.; Yang, L. Parental neglect and social media addiction of adolescents: The Chain mediation effect of basic psychological need and personal growth initiative. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2025, 81, 24–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turel, O.; Serenko, A. The benefits and dangers of enjoyment with social networking websites. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 2012, 21, 512–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skogen, J.C.; Bøe, T.; Finserås, T.R.; Sivertsen, B.; Hella, R.T.; Hjetland, G.J. Lower subjective socioeconomic status ıs associated with increased risk of reporting negative experiences on social media. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 873463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bień, A.; Kulesza-Brończyk, B.; Przestrzelska, M.; Iwanowicz-Palus, G.; Ćwiek, D. The attitudes of polish women towards breastfeeding based on the ıowa infant feeding attitude scale (IIFAS). Nutrients 2021, 13, 4338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioannidis, K.; Treder, M.S.; Chamberlain, S.R.; Kiraly, F.; Redden, S.A.; Stein, D.J.; Grant, J.E. Problematic internet use as an age-related multifaceted problem: Evidence from a two-site survey. Addict. Behav. 2018, 81, 157–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santini, Z.I.; Thygesen, L.C.; Andersen, S.; Tolstrup, J.S.; Koyanagi, A.; Nielsen, L.; Meilstrup, C.; Koushede, V.; Ekholm, O. Social Media Addiction Predicts Compromised Mental Health as well as Perceived and Objective Social Isolation in Denmark: A Longitudinal Analysis of a Nationwide Survey Linked to Register Data. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, A. Maternal trait personality and breastfeeding duration: The importance of confidence and social support. J. Adv. Nurs. 2014, 70, 587–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- İnce, T.; Aktaş, G.; Aktepe, N.; Aydın, A. Annelerin emzirme özyeterlilikleri ve emzirme başarılarını etkileyen özelliklerin değerlendirilmesi. J. Dr. Behçet Uz Child. Hosp. 2017, 7, 181–187. [Google Scholar]

- Cox, K.N.; Giglia, R.C.; Binns, C.W. The influence of infant feeding attitudes on breastfeeding duration: Evidence from a cohort study in rural Western Australia. Int. Breastfeed. J. 2015, 10, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tate, M.K. The ımpact of social comparison via social media on maternal mental health, within the context of the intensive mothering ideology: A scoping review of the literature. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 2023, 44, 854–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conway, R.; Ritchie, I.; Esser, S.; Gilligan, O. Perceived influence of commercial milk formula labelling on mothers’ feeding choices in Great Britain: A qualitative study. Arch. Dis. Child. 2023, 108, 1008–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shensa, A.; Sidani, J.E.; Hoffman, B.L.; Escobar-Viera, C.G.; Melcher, E.M.; Primack, B.A.; Myers, S.P.; Burke, J.G. Positive and Negative Social Media Experiences Among Young Adults With and Without Depressive Symptoms. J. technol. behav. Sci 2021, 6, 378–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chae, J. “Am I a better mother than you?” Media and 21st-century motherhood in the context of the social comparison theory. Commun. Res. 2015, 42, 503–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chee, R.M.; Capper, T.S.; Muurlink, O.T. The ımpact of social media influencers on pregnancy, birth, and early parenting experiences: A systematic review. Midwifery 2023, 120, 103623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samra, A.; Dryer, R. Problematic social media use and psychological distress in pregnancy: The mediating role of social comparisons and body dissatisfaction. J. Affect. Disord. 2024, 361, 702–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prashanth, G.P. Influence of social media on maternal decision-making and breastfeeding practices. World J. Clin. Pediatr. 2024, 13, 94755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.; Ho, Y.; Han, J.; Chen, S. The influence of breastfeeding self-efficacy and breastfeeding intention on breastfeeding behavior in postpartum women. Hu Li Za Zhi J. Nurs. 2018, 65, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kağitcibasi, C.; Ataca, B.; Diri, A. Intergenerational relationships in the family: Ethnic, socioeconomic, and country variations in Germany, Israel, Palestine, and Turkey. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 2010, 41, 652–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Categories | n = 222 | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Education | Primary school | 12 | 5.4 |

| Middle school | 31 | 14.0 | |

| High school | 70 | 31.5 | |

| University | 109 | 49.1 | |

| Economic situation | Income is less than expenses | 38 | 17.1 |

| Income equals expense | 132 | 59.5 | |

| Income is more than the expense | 52 | 23.4 | |

| How many children do you have? | 1 | 136 | 61.3 |

| 2 | 63 | 28.4 | |

| 3 | 21 | 9.5 | |

| 4 | 2 | 0.9 | |

| Currently breastfeeding? | Yes | 197 | 88.7 |

| No | 25 | 11.3 | |

| How many times a day should you feed your baby? | 1–3 | 6 | 3.2 |

| Between 3–7 | 5 | 2.3 | |

| Between 7–10 | 41 | 18.5 | |

| More than 10 | 145 | 65.3 | |

| Not breastfeeding | 25 | 10.8 | |

| If not breastfeeding, why did you stop breastfeeding? | Pregnancy | 1 | 5.88 |

| Breast rejection | 1 | 5.88 | |

| Health | 13 | 76.47 | |

| Curdling of milk | 2 | 11.76 | |

| Switching to supplementary food | Yes | 44 | 19.8 |

| No | 178 | 80.2 | |

| Age | Mean SD | 23.95 2.86 | |

| Minimum–maximum | 18–34 | ||

| How many weeks old is the baby? | Mean SD | 5.39 2.73 | |

| Minimum–maximum | 2–24 | ||

| Duration of breastfeeding for the previous baby (Month). | Mean SD | 17.15 8.36 | |

| Minimum–maximum | 0–24 | ||

| At what age did you switch to supplementary food? | Mean SD | 3.75 2.01 | |

| Minimum–maximum | 1–6 | ||

| Scales | Mean ± SD | Min–Max | Distortion (Skewness) | Kurtosis (Kurtosis) | Questions of Scales | Cronbach Alpha |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1—The State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI-T) | 42.89 8.41 | 21–70 | 0.178 | 0.048 | 20 | 0.826 |

| 2—The Iowa Infant Feeding Attitude Scale (IIFAS) | 66.72 8.09 | 30–84 | −0.864 | 1880 | 17 | 0.665 |

| 3—The Social Media Disorder Scale (SMDS-9) | 8.70 6.10 | 0–32 | 0.782 | 0.544 | 9 | 0.799 |

| 4—Infant Feeding Intentions (IFI) Scale | Categories | n | % | 5 | 0.838 | |

| Low | 6 | 2.7 | ||||

| Middle | 49 | 22.1 | ||||

| Strong | 167 | 75.2 |

| Scales | r & p | Total Score STAI-T | Total Score IIFAS | Total Score SMDS-9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1—The State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI-T) | r p | 1 | ||

| 2—The Iowa Infant Feeding Attitude Scale (IIFAS) | r p | −0.126 0.062 | 1 | |

| 3—The Social Media Disorder Scale (SMDS-9) | r p | 0.076 0.260 | −0.110 0.103 | 1 |

| Scales | IFI Levels | n | SD | F Value | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1—The State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI-T) | Low | 6 | 42.33 ± 10.11 | 2143 | 0.120 |

| Middle | 49 | 45.08 9.38 | |||

| Strong | 167 | 42.27 ± 7.99 | |||

| 2—The Iowa Infant Feeding Attitude Scale (IIFAS) | Low | 6 | 58 10.58 | 6552 | 0.002 |

| Middle | 49 | 64.63 8.27 | |||

| Strong | 167 | 67.65 7.68 | |||

| 3—The Social Media Disorder Scale (SMDS-9) | Low | 6 | 10.16 3.76 | 0.590 | 0.555 |

| Middle | 49 | 9.36 6.34 | |||

| Strong | 167 | 8.46 6.11 |

| Scales | Education Status Levels | n | SD | F Value | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1—The State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI-T) Score | Primary school | 12 | 44.5 8.28 | 0.163 | 0.921 |

| Middle school | 31 | 43.06 8.64 | |||

| High school | 70 | 42.75 8.54 | |||

| University | 109 | 42.76 8.37 | |||

| 2—The Iowa Infant Feeding Attitude Scale (IIFAS) Score | Primary school | 12 | 63.75 8.01 | 0.600 | 0.616 |

| Middle school | 31 | 66.64 8.04 | |||

| High school | 70 | 66.77 7.04 | |||

| University | 109 | 67.05 8.75 | |||

| 3—The Social Media Disorder Scale (SMDS-9) Score | Primary school | 12 | 7.5 6.34 | 2658 | 0.049 |

| Middle school | 31 | 6.54 5.04 | |||

| High school | 70 | 10.05 6.12 | |||

| University | 109 | 8.58 6.20 |

| Scales | Income Levels | n | SD | F Value | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1—The State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI-T) Score | Income is less than expenses | 38 | 43.68 8.81 | 1532 | 0.208 |

| Income equals expense | 132 | 43.37 8.38 | |||

| Income is more than the expense | 52 | 41.09 8.08 | |||

| 2—The Iowa Infant Feeding Attitude Scale (IIFAS) Score | Income is less than expenses | 38 | 67.13 10.66 | 0.117 | 0.889 |

| Income equals expense | 132 | 66.51 7.81 | |||

| Income is more than the expense | 52 | 66.98 6.62 | |||

| 3—The Social Media Disorder Scale (SMDS-9) Score | Income is less than expenses | 38 | 6.68 5.54 | 3163 | 0.044 |

| Income equals expense | 132 | 8.81 ± 5.94 | |||

| Income is more than the expense | 52 | 9.90 6.63 |

| Variables | The State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI-T) Score | The Iowa Infant Feeding Attitude Scale (IIFAS) Score | The Social Media Disorder Scale (SMDS-9) Score | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | r | 0.043 | 0.147 | −0.231 |

| p | 0.525 | 0.028 | 0.001 | |

| How many weeks old is the baby? | r | 0.061 | 0.114 | 0.044 |

| p | 0.368 | 0.090 | 0.515 | |

| Duration of breastfeeding for the previous baby. | r | −0.242 | 0.090 | 0.149 |

| p | 0.027 | 0.414 | 0.177 | |

| At what age does a baby start to eat supplementary food? | r | −0.018 | 0.508 | −0.245 |

| p | 0.932 | 0.008 | 0.227 | |

| Scales | Categories | IFI Levels | Chi Square | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low n (%) | Middle n (%) | Strong n (%) | ||||

| Education Status | Primary school | 1 (8.3) | 2 (16.7) | 9 (75) | 0.076 | 0.823 |

| Middle school | 1 (3.2) | 4 (12.9) | 26 (83.9) | |||

| High school | 3 (4.3) | 18 (25.7) | 49 (70) | |||

| University | 1 (0.9) | 25 (22.9) | 83 (76.1) | |||

| Economic situation | Income is less than expenses | 0 (0) | 7 (18.4) | 31 (81.6) | 3694 | 0.059 |

| Income equals expense | 3 (2.3) | 28 (21.2) | 101 (76.5) | |||

| Income is more than the expense | 3 (5.8) | 14 (26.9) | 35 (67.3) | |||

| The current number of children. | 1 | 3 (2.2) | 34 (25) | 99 (72.8) | 0.727 | 0.450 |

| 2 | 2(3.2) | 12 (19) | 49 (77.8) | |||

| 3 | 1 (4.8) | 3 (14.2) | 17 (81) | |||

| 4 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (100) | |||

| Is the mother breastfeeding the baby? | Yes | 2 (1) | 43(21.8) | 152 (77.2) | 9007 | 0.005 |

| No | 4 (16) | 6 (24) | 15 (60) | |||

| How many times a day does she breastfeed? | 1–3 | 1 (33.3) | 2 (4.7) | 4 (2.6) | 5873 | 0.017 |

| Between 3–7 | 1 (33.3) | 1 (2.3) | 3 (60) | |||

| Between 7–10 | 1 (33.3) | 9 (20.9) | 31 (2) | |||

| More than 10 | 0 (0) | 31 (72.1) | 114 (75) | |||

| Switching to supplementary food | Yes | 4 (66.7) | 12 (24.5) | 28 (16.8) | 6969 | 0.012 |

| No | 2 (33.3) | 37 (75.5) | 139 (83.2) | |||

| Scales | IFI Levels | n | SD | F Value | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Low | 6 | 23.83 ± 2.99 | 0.078 | 0.925 |

| Middle | 49 | 23.81 2.88 | |||

| Strong | 167 | 23.99 2.86 | |||

| How many weeks old is the baby? | Low | 6 | 5.08 ± 2.24 | 0.039 | 0.961 |

| Middle | 49 | 5.40 2.76 | |||

| Strong | 167 | 5.40 2.75 | |||

| Duration of breastfeeding the previous baby | Low | 6 | 4 6.92 | 4931 | 0.010 |

| Middle | 49 | 15.50 8.95 | |||

| Strong | 167 | 18.17 7.78 | |||

| At what age does a baby start to eat supplementary food? | Low | 6 | 5 | 0.193 | 0.826 |

| Middle | 49 | 3.75 1.90 | |||

| Strong | 167 | 3.67 2.18 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tosun, H.; Özkan, H. Problematic Social Media Use and Its Relationship with Breastfeeding Behaviors and Anxiety in Social Media-Native Mothers: A Mixed-Methods Study. Healthcare 2025, 13, 2216. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13172216

Tosun H, Özkan H. Problematic Social Media Use and Its Relationship with Breastfeeding Behaviors and Anxiety in Social Media-Native Mothers: A Mixed-Methods Study. Healthcare. 2025; 13(17):2216. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13172216

Chicago/Turabian StyleTosun, Hülya, and Hava Özkan. 2025. "Problematic Social Media Use and Its Relationship with Breastfeeding Behaviors and Anxiety in Social Media-Native Mothers: A Mixed-Methods Study" Healthcare 13, no. 17: 2216. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13172216

APA StyleTosun, H., & Özkan, H. (2025). Problematic Social Media Use and Its Relationship with Breastfeeding Behaviors and Anxiety in Social Media-Native Mothers: A Mixed-Methods Study. Healthcare, 13(17), 2216. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13172216

_MD__MPH_PhD.png)