Quality of Life and Fatigue in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Objective

2.2. Search Strategy

2.3. Eligibility Criteria

2.3.1. Inclusion Criteria

- Studies must have investigated IBD (including ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease) with established diagnostic parameters;

- Studies must have graded quality of life using any validated instrument;

- Studies must have assessed fatigue using any validated instrument;

- Studies must involve an adult study population;

- Studies must have compared quality of life in people diagnosed with IBD with a normal population;

- Studies must have designed and included randomized controlled trials, cross-sectional, retrospective, prospective, and other controlled studies.

2.3.2. Exclusion Criteria

- Studies investigating non-fatigue comorbidities;

- Conference abstracts, posters, commentaries, and letters;

- Case reports, case series, or qualitative research;

- Animal studies.

2.4. Study Selection

2.5. Data Extraction

- Authors, publication year, study design, and setting;

- Participant characteristics, including IBD subtype, sex, disease activity status, and sample size;

- Outcome measures and results for the primary outcomes.

2.6. Quality Assessment Studies

2.7. Data Synthesis

3. Results

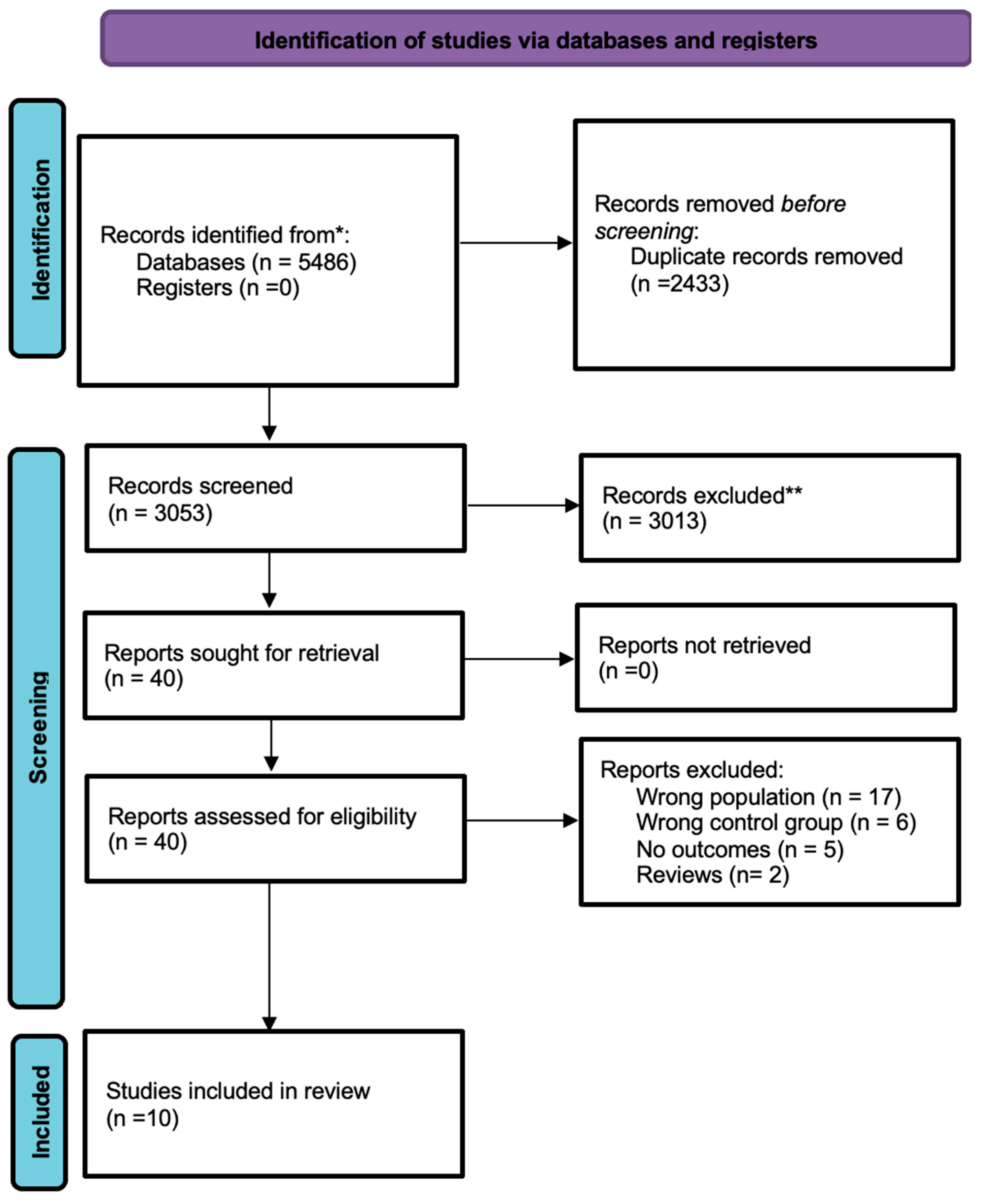

- 40 studies underwent full-text assessment;

- Of all 40, only 10 studies were included in the final analysis for meeting the inclusion parameters.

3.1. Study Characteristics

- A total of 10,661 participants were included.

- Study designs:

- ⚬

- Cross-sectional studies (n = 4);

- ⚬

- Cohort studies (n = 6).

- Study settings:

- ⚬

- Hospital-based studies (n = 6);

- ⚬

- Community-based studies (n = 3).

- Median follow-up duration: 4.89 years (range: 0.12–8.66 years);

- Gender distribution: 54% male, 46% female;

- The quality of every study included was graded from good to fair quality (Tables S1 and S2);

- Cross-sectional studies included fewer than 400 participants, while all other studies received high scores for selection, comparability, and outcome assessment.

3.2. Quality of Life

3.3. Fatigue

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| HRQoL | Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| IBD | inflammatory bowel diseases |

| QoL | quality of life |

| MDs | mean differences |

| SIBDQ | Short Inflammatory Bowel Disease Questionnaire |

| CD | Chron’s disease |

References

- Lönnfors, S.; Vermeire, S.; Avedano, L. IBD and health-related quality of life—Discovering the true impact. J. Crohn’s Colitis 2014, 8, 1281–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Silva, A.; Fox, D.E.; Nasser, Y.; Vallance, J.K.; Quinn, R.R.; Ronksley, P.E.; Raman, M. Prevalence and risk factors for fatigue in adults with inflammatory bowel disease: A systematic review with meta-analysis. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2022, 20, 995–1009.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popov, J.; Farbod, Y.; Chauhan, U.; Kalantar, M.; Hill, L.; Armstrong, D.; Halder, S.; Marshall, J.K.; Moayyedi, P.; Kaasalainen, S. Patients’ Experiences and Challenges in Living with Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Qualitative Approach. Clin. Exp. Gastroenterol. 2021, 14, 123–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, D.T.; Peyrin-Biroulet, L.; Reinisch, W.; Tole, S.; Sullivan, L.; Park, K.T.; Regueiro, M. Inflammatory Bowel Disease Patients’ Perspectives of Clinical Trials: A Global Quantitative and Qualitative Analysis. Crohns Colitis 360 2021, 3, otab079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreiner, P.; Rossel, J.B.; Biedermann, L.; Valko, P.O.; Baumann, C.R.; Greuter, T.; Scharl, M.; Vavricka, S.R.; Pittet, V.; Juillerat, P.; et al. Fatigue in inflammatory bowel disease and its impact on daily activities. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2021, 53, 138–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maddineni, G.; AAkash, F.N.U.; Rehman, O.; Salami, A. Global burden of ibd: A comparative analysis of the two most affected regions (1990–2021). Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2025, 31 (Suppl. S1), S30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borren, N.Z.; van der Woude, C.J.; Ananthakrishnan, A.N. Fatigue in IBD: Epidemiology, pathophysiology and management. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019, 16, 247–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minderhoud, I.M.; Oldenburg, B.; Van Dam, P.S.; van Berge Henegouwen, G.P. High prevalence of fatigue in quiescent inflammatory bowel disease is not related to adrenocortical insufficiency. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2003, 98, 1088–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jelsness-Jørgensen, L.-P.; Bernklev, T.; Henriksen, M.; Torp, R.; Moum, B.A. Chronic fatigue is more prevalent in patients with inflammatory bowel disease than in healthy controls. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2011, 17, 1564–1572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Langenberg, D.; Gibson, P.R. Systematic review: Fatigue in inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2010, 32, 131–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knowles, S.R.; Graff, L.A.; Wilding, H.; Hewitt, C.; Keefer, L.; Mikocka-Walus, A. Quality of life in inflammatory bowel disease: A systematic review and meta-analyses—Part I. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2018, 24, 742–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ouzzani, M.; Hammady, H.; Fedorowicz, Z.; Elmagarmid, A. Rayyan—A web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst. Rev. 2016, 5, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wells, G.A.; Shea, B.; O’Connell, D.; Peterson, J.; Welch, V.; Losos, M.; Tugwell, P. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for Assessing the Quality of Nonrandomised Studies in Meta-Analyses. 2000. Available online: https://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp (accessed on 19 May 2025).

- DerSimonian, R.; Laird, N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control. Clin. Trials 1986, 7, 177–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlQahtani, M.; AlHarbi, R.; AlAsmari, R.; AlNowaiser, L.; AlThunayan, E.; Alzaben, A.S. Health-Related Quality of Life in Individuals with Crohn’s Disease: A Sample from Saudi Arabia. J. Allied Health 2022, 51, 104–109. [Google Scholar]

- Bulut, E.A.; Törüner, M. The influence of disease type and activity to sexual life and health quality in inflammatory bowel disease. Turk. J. Gastroenterol. 2018, 30, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogut, A.; Martinac, M.; Pravdić, D.; Karin, M.; Volarić, M.; Bevanda Glibo, D.; Babić, E.; Babić, D.; Bevanda, M. Personality Traits and Health Related Quality of Life in Patients with Irritable Bowel Sindrome and Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Psychiatr. Danub. 2022, 34 (Suppl. S10), 53–62. [Google Scholar]

- Grimstad, T.; Skjellerudsveen, B.M.; Kvaløy, J.T.; Skoie, I.M.; Carlsen, A.; Karlsen, L.N.; Aabakken, L.; Omdal, R. The influence of disease activity on fatigue in patients with ulcerative colitis–a longitudinal study. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 2022, 57, 290–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holten, K.I.A.; Bernklev, T.; Opheim, R.; Johansen, I.; Olsen, B.C.; Lund, C.; Strande, V.; Medhus, A.W.; Perminow, G.; Bengtson, M.-B.; et al. Fatigue in patients with newly diagnosed inflammatory bowel disease: Results from a prospective inception cohort, the IBSEN III study. J. Crohn’s Colitis 2023, 17, 1781–1790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunovský, L.; Mitáš, L.; Marek, F.; Dolina, J.; Poredska, K.; Kučerová, L.; Benesova, K.; Kala, Z. Impact of surgery on quality of life in Crohn s disease patients: Final results of Czech cohort. Vnitřní Lékařství 2018, 64, 347–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, F.; Tu, L.; Li, J.; Chen, Y.; Xu, M.; Zhu, L. Psychological aspect of patients with inflammatory bowel disease, which may be related to the quality of life, sleep and disease characteristics. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 2021, 56, 1328–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trieschmann, K.; Chang, L.; Park, S.; Naliboff, B.; Joshi, S.; Labus, J.S.; Sauk, J.S.; Limketkai, B.N.; Mayer, E.A. The visceral sensitivity index: A novel tool for measuring GI-symptom-specific anxiety in inflammatory bowel disease. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2022, 34, e14384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveira, R.; Martins, V.; de Sousa, H.T.; Roseira, J. Food-Related Quality of Life and Its Predictors in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2024, 69, 1793–1802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romberg-Camps, M.; Bol, Y.; Dagnelie, P.; Hesselink-Van De Kruijs, M.; Kester, A.; Engels, L.; van Deursen, C.; Hameeteman, W.H.A.; Pierik, M.; Wolters, F.; et al. Fatigue and health-related quality of life in inflammatory bowel disease: Results from a population-based study in the Netherlands: The IBD-South Limburg cohort. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2010, 16, 2137–2147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavarría, C.; Casanova, M.; Chaparro, M.; Barreiro-de Acosta, M.; Ezquiaga, E.; Bujanda, L.; Rivero, M.; Argüelles-Arias, F.; Martín-Arranz, M.D.; Martínez-Montiel, M.P.; et al. Prevalence and factors associated with fatigue in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: A multicentre study. J. Crohn’s Colitis 2019, 13, 996–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artom, M.; Czuber-Dochan, W.; Sturt, J.; Murrells, T.; Norton, C. The contribution of clinical and psychosocial factors to fatigue in 182 patients with inflammatory bowel disease: A cross-sectional study. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2017, 45, 403–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burisch, J.; Jess, T.; Martinato, M.; Lakatos, P.L.; ECCO-EpiCom. The burden of inflammatory bowel disease in Europe. J. Crohn’s Colitis 2013, 7, 322–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Gönczi, L.; Lakatos, P.L.; Burisch, J. The burden of inflammatory bowel disease in Europe in 2020. J. Crohn’s Colitis 2021, 15, 1573–1587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| SN | Study Author, Year | Study Design | Setting | Study Duration | Participant Characteristics (Sample Size) | % of Gender | Measures of QoL | Measures of Fatigue |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | AlQahtani, 2022 [16] | Cross-sectional | Community | 45 days | Crohn’s disease: 109 Healthy control: 370 | Crohn’s disease M: 55% F: 45% Control M: 26% F: 74% | SF-36 | NR |

| 2 | Bulut, 2019 [17] | Cross-sectional | Community | 9 months | IBD:122 Control:42 | CD: M: 41.3% F: 58.6% UC: M: 54.68% F: 45.31% Control M: 47.6% F: 52.38% | SF-36 | NR |

| 3 | Bogut, 2022 [18] | Cross-sectional | Hospital | 6 months | IBS: 40 IBD: 40 Control: 40 | (IBS): M: 0% F:40% IBD: M: 55%; F: 45% Control: M: 42.5%; F: 57.5% | SF-36 | NR |

| 4 | Grimstad, 2022 [19] | Cohort | Hospital | 5 years, 9 months | UC: 149 Control: 22 | UC: M: 54.3%; F: 45.7% Control M: 45.5%; F: 54.5% | NR | Fatigue Severity Scale (FSS) |

| 5 | Holten, 2023 [20] | Cohort | Hospital | 3 years | IBD: 983 Control: 2287 | UC vs. Control M: 49.6%; F: 72.1% CD vs. Control M: 56.2%; F: 79.2% | NR | Generic Fatigue Questionnaire [FQ] |

| 6 | Kunovsky, 2018 [21] | Cohort | Hospital | 6 years | CD: 215 Control: 104 | Operated: M: 44.7%; F: 55.3% Non-operated: M: 33.7%; F: 66.3%; Control: M: 40.4%; F: 59.6% | QLQ-CR29 questionnaire | NR |

| 7 | Ling, 2021 [22] | Cohort | Hospital | 2 years | Diseased: 112 Control: 165 | IBD: M: 67.9%; F: 32.1% UC: M: 66.7%; F: 33.3% CD: M: 68.5%; F: 31.5% Control: M: 67.9%; F: 32.1% | SF-36 | NR |

| 8 | Schreiner, 2021 [5] | Cohort | Hospital | 1.2 years | IBD: 1208 Control: 414 | IBD: M: 63.4%; Control M: 41.2% | NR | Visual analogue scale and Fatigue Severity Scale (FSS) |

| 9 | Trieschmann, 2022 [23] | Cohort | Community advertisement | 8 years, 8 months | IBD: 74 IBS: 74 Control: 74 | Diseased IBD: F: 40% IBS: F: 40% Control: F: 40% | SF-12 | NR |

| 10 | Oliveira, 2024 [24] | Cross-sectional case–control study | Hospital | NA | CD: 69 UC: 170 Control: 126 | CD: 63.8 UC: 53.5 Control: 46.8 | Short Inflammatory Bowel Disease Questionnaire | NR |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Abdulla, M.; Mohammed, N.; AlQamish, J.; Sawaf, B. Quality of Life and Fatigue in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Systematic Review. Healthcare 2025, 13, 2203. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13172203

Abdulla M, Mohammed N, AlQamish J, Sawaf B. Quality of Life and Fatigue in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Systematic Review. Healthcare. 2025; 13(17):2203. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13172203

Chicago/Turabian StyleAbdulla, Maheeba, Nafeesa Mohammed, Jehad AlQamish, and Bisher Sawaf. 2025. "Quality of Life and Fatigue in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Systematic Review" Healthcare 13, no. 17: 2203. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13172203

APA StyleAbdulla, M., Mohammed, N., AlQamish, J., & Sawaf, B. (2025). Quality of Life and Fatigue in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Systematic Review. Healthcare, 13(17), 2203. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13172203