The Role of Doctor Visits, Body Image Discrepancy, and Perceived Health in Predicting Medical Weight Problem Diagnosis

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Importance of Medical Diagnosis of Obesity

1.2. Body Image Discrepancy

1.3. Perceived Health Status

1.4. Purpose of Current Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Procedures

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Health Survey

2.3.2. Stunkard Figure Rating Scale (SFRS) [34]

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sample Descriptive Characteristics

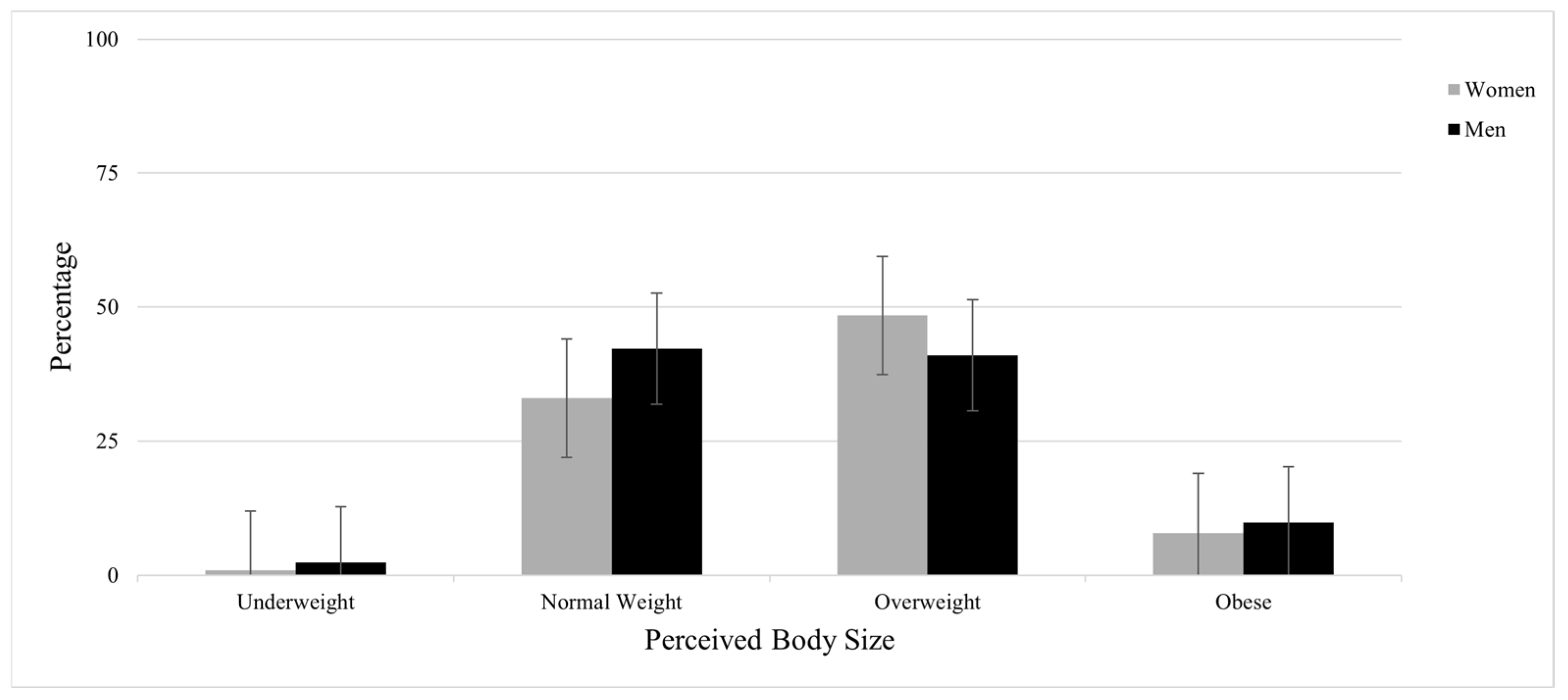

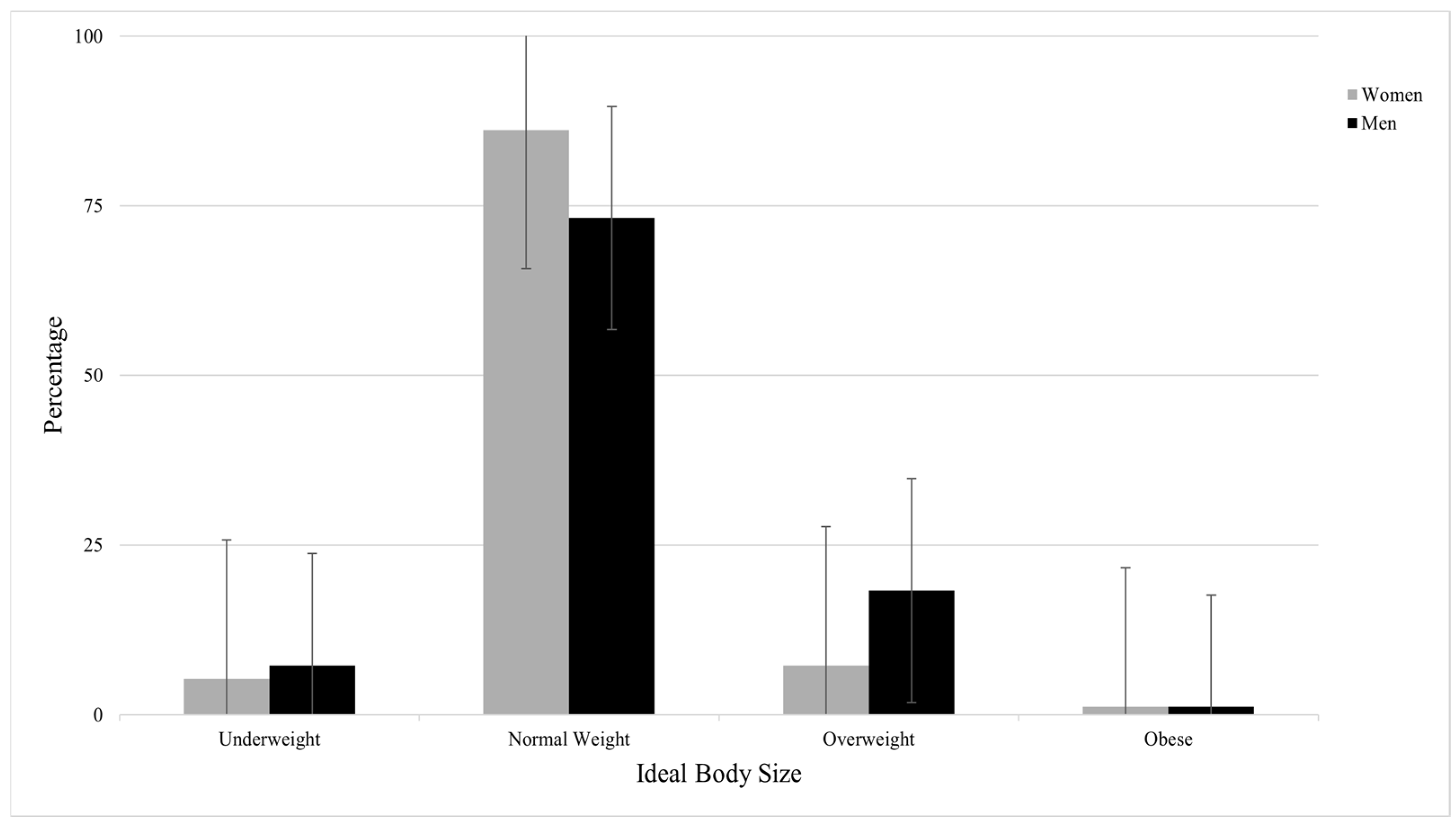

3.2. Perceived and Ideal Body Size and Body Image Discrepancy

3.3. Logistic Regression Analysis to Predict Medical Weight Problem Diagnosis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, Y.; Beydoun, M.A.; Min, J.; Xue, H.; Kaminsky, L.A.; Cheskin, L.J. Has the Prevalence of Overweight, Obesity and Central Obesity Levelled off in the United States? Trends, Patterns, Disparities, and Future Projections for the Obesity Epidemic. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2020, 49, 810–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Center for Disease Control (CDC). Overweight & Obesity. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/obesity/basics/consequences.html/ (accessed on 6 August 2025).

- Bae, J.P.; Nelson, D.R.; Boye, K.S.; Mather, K.J. Prevalence of Complications and Comorbidities Associated with Obesity: A Health Insurance Claims Analysis. BMC Public Health 2025, 25, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Center for Disease Control (CDC). Prevalence of Obesity and Severe Obesity Among Adults: United States 2017–2018. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db360.htm (accessed on 21 August 2025).

- Wolfe, M.K.; McDonald, N.C.; Holmes, G.M. Transportation Barriers to Health Care in the United States: Findings From the National Health Interview Survey, 1997–2017. Am. J. Public Health 2020, 110, 815–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galvan, T.; Lill, S.; Garcini, L.M. Another Brick in the Wall: Healthcare Access Difficulties and Their Implications for Undocumented Latino/a Immigrants. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2021, 23, 885–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alemán, J.O.; Almandoz, J.P.; Frias, J.P.; Galindo, R.J. Obesity Among Latinx People in the United States: A review. Obesity 2023, 31, 329–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavina, C.; Borges, A.; Afonso-Silva, M.; Fortuna, I.; Canelas-Pais, M.; Amaral, R.; Costa, I.; Seabra, D.; Araújo, F.; Tavei-ra-Gomes, T. Patients’ Health Care Resources Utilization and Costs Estimation Across Cardiovascular Risk Categories: Insights from the LATINO Study. Health Econ. Rev. 2024, 14, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Center for Disease Control (CDC). Ambulatory Care Use and Physician Office Visits. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/physician-visits.htm (accessed on 21 August 2025).

- World Health Organization. Obesity and Overweight. Available online: http://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight (accessed on 16 July 2021).

- Pantalone, K.M.; Hobbs, T.M.; Chagin, K.M.; Kong, S.X.; Wells, B.J.; Kattan, M.W.; Bouchard, J.; Sakurada, B.; Milinovich, A.; Weng, W.; et al. Prevalence and Recognition of Obesity and Its Associated Comorbidities: Cross-Sectional Analysis of Electronic Health Record Data from a Large US Integrated Health System. BMJ Open 2017, 7, e017583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loprinzi, P.D.; Davis, R.E. Promotion of Weight Loss by Health-Care Professionals: Implications for Influencing Weight Loss/Control Behaviors. Am. J. Health Promot. 2016, 31, 417–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mainous, A.G.; Xie, Z.; Dickmann, S.B.; Medley, J.F.; Hong, Y.-R. Documentation and Treatment of Obesity in Primary Care Physician Office Visits: The Role of the Patient-Physician Relationship. J. Am. Board Fam. Med. 2023, 36, 325–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenoir, L.; Maillot, M.; Guilbot, A.; Ritz, P. Primary Care Weight Loss Maintenance with Behavioral Nutrition: An Observational Study. Obesity 2015, 23, 1771–1777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pool, A.C.; Kraschnewski, J.L.; Cover, L.A.; Lehman, E.B.; Stuckey, H.L.; Hwang, K.O.; Pollak, K.I.; Sciamanna, C.N. The Impact of Physician Weight Discussion on Weight Loss in US Adults. Obes. Res. Clin. Pract. 2014, 8, e131–e139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, D.A.; Bray, G.A.; Ryan, D.H. Is 5% Weight Loss a Satisfactory Criterion to Define Clinically Significant Weight Loss? Obesity 2015, 23, 2319–2320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fitzpatrick, S.L.; Stevens, V.J. Adult Obesity Management in Primary Care, 2008–2013. Prev. Med. 2017, 99, 128–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaplan, L.M.; Golden, A.; Jinnett, K.; Kolotkin, R.L.; Kyle, T.K.; Look, M.; Nadglowski, J.; O’Neil, P.M.; Parry, T.; Tomaszewski, K.J.; et al. Perceptions of Barriers to Effective Obesity Care: Results from the National ACTION Study. Obesity 2017, 26, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrd, A.S.; Toth, A.T.; Stanford, F.C. Racial Disparities in Obesity Treatment. Curr. Obes. Rep. 2018, 7, 130–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, H.T.; Markides, K.S.; Winkleby, M.A. Physician Advice on Exercise and Diet in a U.S. Sample of Obese Mexi-can-American Adults. Am. J. Health Promot. 2011, 25, 402–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, K.H.; Gudzune, K.A.; Fischer, H.; Yamamoto, A.; Young, D.R. Racial and Ethnic Minority Patients Report Different Weight-Related Care Experiences Than Non-Hispanic Whites. Prev. Med. Rep. 2016, 4, 296–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, K.L.; Lillis, J.; Panza, E.; Wing, R.R.; Quinn, D.M.; Puhl, R.R. Body Shape Concerns Across Racial and Ethnic Groups Among Adults in the United States: More Similarities than Differences. Body Image 2020, 35, 108–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinberger, N.-A.; Kersting, A.; Riedel-Heller, S.G.; Luck-Sikorski, C. Body Dissatisfaction in Individuals with Obesity Com-pared to Normal-Weight Individuals: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Obes. Facts 2016, 9, 424–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruszka, W.; Owczarek, A.J.; Glinianowicz, M.; Bąk-Sosnowska, M.; Chudek, J.; Olszanecka-Glinianowicz, M. Perception of Body Size and Body Dissatisfaction in Adults. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, M.; Winter, V.R.; O’Neill, E.A. Body Appreciation and Health Care Avoidance: A Brief Report. Health Soc. Work. 2020, 45, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Austin, J.L.; Serier, K.N.; Sarafin, R.E.; Smith, J.E. Body Dissatisfaction Predicts Poor Behavioral Weight Loss Treatment Ad-herence in Overweight Mexican American Women. Body Image 2017, 23, 155–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldstein, M.S.; Siegel, J.M.; Boyer, R. Predicting Changes in Perceived Health Status. Am. J. Public Health 1984, 74, 611–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenstock, I. The Health Belief Model: Explaining Health Behavior through Expectancies. Health Behav. Health Educ. Theory Res. Pract. 1990, 460, 39–62. [Google Scholar]

- Faghih, M.; Kaveh, M.H.; Nazari, M.; Khademi, K.; Hasanzadeh, J. Effect of Health Belief Model-Based Training and Social Support on the Physical Activity of Overweight Middle-Aged Women: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Front. Public Health 2024, 12, 1250152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idema, C.L.; Roth, S.E.; Upchurch, D.M. Weight Perception and Perceived Attractiveness Associated with Self-Rated Health in Young Adults. Prev. Med. 2019, 120, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Essayli, J.H.; Murakami, J.M.; Wilson, R.E.; Latner, J.D. The Impact of Weight Labels on Body Image, Internalized Weight Stigma, Affect, Perceived Health, and Intended Weight Loss Behaviors in Normal-Weight and Overweight College Women. Am. J. Health Promot. 2016, 31, 484–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reesor, L.; Canales, S.; Alonso, Y.; Kamdar, N.P.; Hernandez, D.C. Self-Reported Health Predicts Hispanic Women’s Weight Perceptions and Concerns. Am. J. Health Behav. 2018, 42, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olvera, N.; Matthews-Ewald, M.; Zhang, R.; Scherer, R.; Fan, W.; Arbona, C. Weight Concern and Body Image Dissatisfaction among Hispanic and African American Women. Women 2023, 3, 486–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stunkard, A.J.; Sørensen, T.; Schulsinger, F. Use of the Danish Adoption Register for the study of Obesity and Thinness. Res. Publ. Assoc. Res. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 1983, 60, 115–120. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, J.K.; Altabe, M.N. Psychometric Qualities of the Figure Rating Scale. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 1991, 10, 615–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peña, C.M.; Guajardo, E.P. Body Image Distortion and Dissatisfaction in a mexican sample. Rev. Psicol. Cienc. Comport. Unidad acad. Cienc. Juríd. Soc. 2018, 9, 120–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Aldao, D.; Diz, J.; Varela, S.; Sanchez-Lastra, M.A.; Pérez, C.A. Reliability and validity of the SAPF questionnaire and the Stunkard rating scale amongst elderly Spanish people. An. Sist. Sanit. Navar. 2021, 44, 327–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CDC. Adult BMI Categories. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/bmi/adult-calculator/bmi-categories.html (accessed on 18 June 2025).

- Bowring, A.L.; Peeters, A.; Freak-Poli, R.; Lim, M.S.; Gouillou, M.; Hellard, M. Measuring the Accuracy of Self-Reported Height and Weight in a Community-Based Sample of Young People. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2012, 12, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olfert, M.D.; Barr, M.L.; Charlier, C.M.; Famodu, O.A.; Zhou, W.; Mathews, A.E.; Byrd-Bredbenner, C.; Colby, S.E. Self-Reported vs. Measured Height, Weight, and BMI in Young Adults. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiggemann, M.; Lynch, J.E. Body Image Across the Life Span in Adult Women: The Role of Self-Objectivitation. Dev. Psychol. 2001, 27, 243–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rojas-Guyler, L.; King, K.A.; Montieth, B.A. Health-Seeking Behaviors among Latinas: Practices and Reported Difficulties in Obtaining Health Services. Am. J. Health Educ. 2008, 39, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, M.; Michaels-Obregón, A.; Rocha, K.O.; Wong, R. Imputation of Non-Response in Height and Weight in the Mexican Health and Aging Study. Real. Datos Y Espac. Rev. Int. De Estad. Y Geogr. 2022, 13, 78–93. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Salgado, D.; Flores, J.V.; Janssen, I.; Ortiz-Hernández, L. Diagnosis and Treatment of Obesity among Mexican Adults. Obes. Facts 2012, 5, 937–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winter, V.R.; Trout, K.; Harrop, E.; O’nEill, E.; Puhl, R.; Bartlett-Esquilant, G. Women’s Refusal to Be Weighed During Healthcare Visits: Links to Body Image. Body Image 2023, 46, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Women (n = 366) | Men (n = 92) |

|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | |

| Self-perceived Health Status | ||

| Very Poor | 4 (1.1) | 3 (3.3) |

| Poor | 18 (4.9) | 3 (3.3) |

| Average | 142 (38.8) | 25 (27.2) |

| Good | 130 (35.5) | 41 (44.6) |

| Very Good | 55 (15.0) | 9 (9.8) |

| Not Sure | 13 (3.6) | 6 (6.5) |

| Did Not Answer | 4 (1.1) | 5 (5.4) |

| Doctor Visit past 12 Months | ||

| Yes | 304 (83.1) | 74 (80.4) |

| No | 54 (14.8) | 17 (18.5) |

| Did Not Answer | 8 (2.2) | 1 (1.1) |

| Medical Weight Problem Diagnosis | ||

| Yes | 116 (31.7) | 26 (28.3) |

| No | 183 (50.0) | 40 (43.5) |

| Did Not Answer | 67 (18.3) | 26 (28.3) |

| Obesity Status | ||

| Underweight | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Normal Weight | 56 (15.3) | 8 (8.7) |

| Overweight | 79 (21.6) | 30 (32.6) |

| Obese | 109 (29.8) | 20 (21.7) |

| Did Not know (weight or heigh) | 122 (33.3) | 34 (37.0) |

| 95% CI | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participants | Variables | B | Wald | Exp(B) | LL | UL |

| Women | Age | −0.005 | 0.22 | 1.00 | 0.97 | 1.02 |

| Doctor Visit(s) | 1.61 ** | 11.56 | 5.02 | 1.98 | 12.73 | |

| Health Status | −0.47 ** | 10.97 | 0.63 | 0.47 | 0.83 | |

| BID | 0.63 ** | 28.55 | 1.88 | 1.49 | 2.37 | |

| Men | Age | 0.01 | 0.13 | 1.01 | 0.97 | 1.05 |

| Doctor Visit(s) | 2.65 * | 5.45 | 14.17 | 1.53 | 131.17 | |

| Health Status | −0.30 | 1.32 | 0.74 | 0.45 | 1.23 | |

| BID | 0.47 * | 3.99 | 1.60 | 1.01 | 2.54 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Olvera, N.; Scherer, R.; Wu, W.; Roy, T.J.; Matthews-Ewald, M.R.; Fan, W.; Arbona, C. The Role of Doctor Visits, Body Image Discrepancy, and Perceived Health in Predicting Medical Weight Problem Diagnosis. Healthcare 2025, 13, 2135. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13172135

Olvera N, Scherer R, Wu W, Roy TJ, Matthews-Ewald MR, Fan W, Arbona C. The Role of Doctor Visits, Body Image Discrepancy, and Perceived Health in Predicting Medical Weight Problem Diagnosis. Healthcare. 2025; 13(17):2135. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13172135

Chicago/Turabian StyleOlvera, Norma, Rhonda Scherer, Weiwei Wu, Tamal J. Roy, Molly R. Matthews-Ewald, Weihua Fan, and Consuelo Arbona. 2025. "The Role of Doctor Visits, Body Image Discrepancy, and Perceived Health in Predicting Medical Weight Problem Diagnosis" Healthcare 13, no. 17: 2135. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13172135

APA StyleOlvera, N., Scherer, R., Wu, W., Roy, T. J., Matthews-Ewald, M. R., Fan, W., & Arbona, C. (2025). The Role of Doctor Visits, Body Image Discrepancy, and Perceived Health in Predicting Medical Weight Problem Diagnosis. Healthcare, 13(17), 2135. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13172135