Mind–Body Practices for Mental Health in Higher Education: Breathing, Grounding, and Consistency Are Essential for Stress and Anxiety Management

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

1.2. The Present Study

1.3. Aims and Research Questions

2. Methods

2.1. Procedures

2.1.1. Questionnaires

2.1.2. Data Analysis

2.1.3. Ethics

2.2. Participants

3. Results

3.1. Mental Health

3.2. Mind–Body Coping Strategies

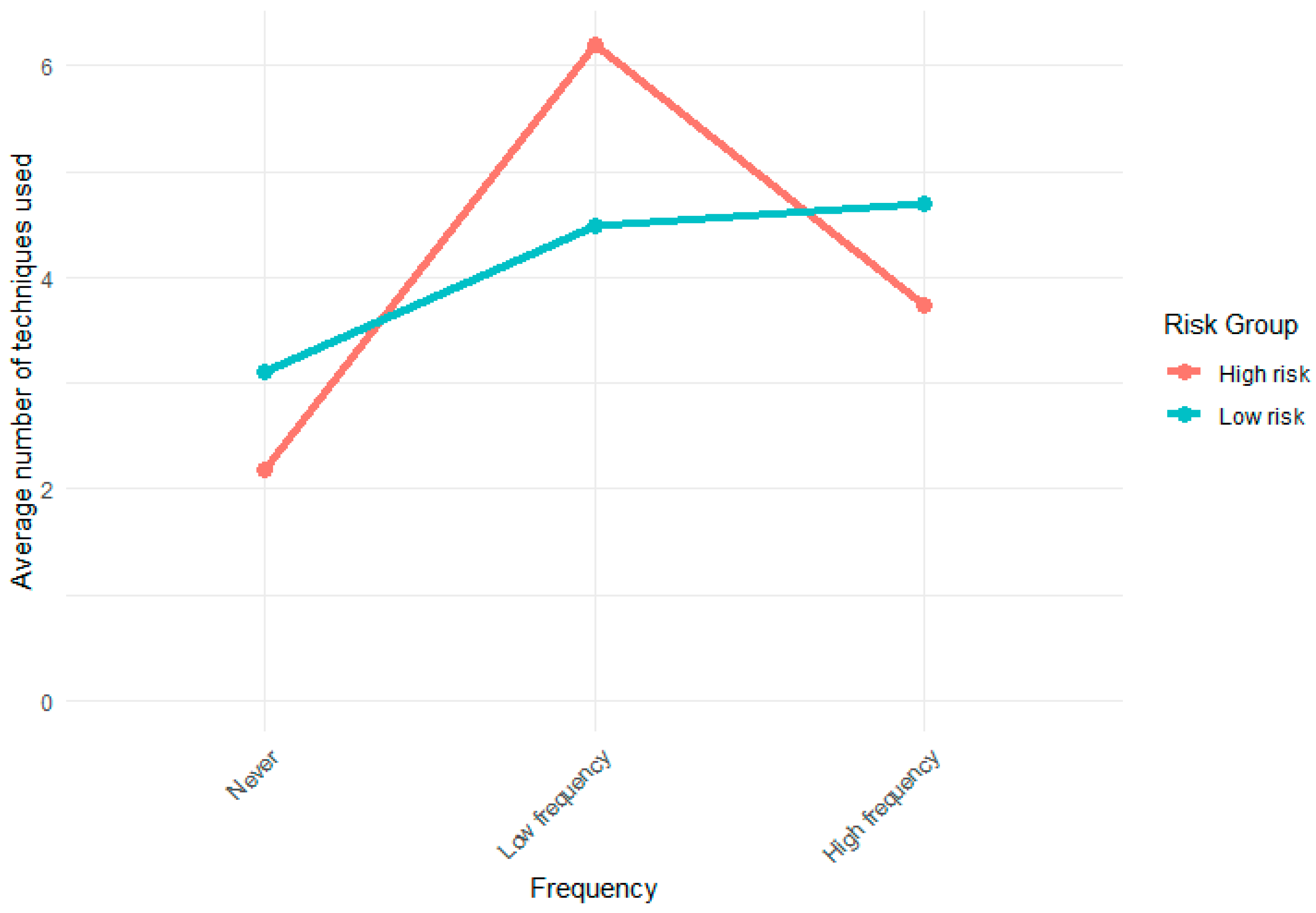

3.3. The High-Risk vs. The Low-Risk Group

4. Discussion

Study Limitations

5. Conclusions and Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Brown, J.S.L. Student mental health: Some answers and more questions. J. Ment. Health 2018, 27, 193–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lipson, S.K.; Zhou, S.; Abelson, S.; Heinze, J.; Jirsa, M.; Morigney, J.; Patterson, A.; Singh, M.; Eisenberg, D. Trends in college student mental health and help-seeking by race/ethnicity: Findings from the national healthy minds study, 2013–2021. J. Affect. Disord. 2022, 306, 138–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danmarks Evalueringsinstitut. Kortlægning af Trivsel på Universiteterne; DJØF: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2023; ISBN 978-87-7182-653-1. [Google Scholar]

- Ungetrivselsrådet. Ungetrivselsanalyse; Ungetrivselsrådet: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2022; Available online: https://psykiatrifonden.dk/files/media/document/Ungetrivselanalyse_ungetrivselsraadet_juni_2022.pdf (accessed on 27 July 2025).

- Hjorth, C.F.; Bilgrav, L.; Frandsen, L.S.; Overgaard, C.; Torp-Pedersen, C.; Nielsen, B.; Bøggild, H. Mental health and school dropout across educational levels and genders: A 4.8-year follow-up study. BMC Public Health 2016, 16, 976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazarus, R.S.; Folkman, S. Stress, Appraisal, and Coping; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1984; ISBN 978-0-8261-4191-0. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, J.R.; Chan, F.; Iwanaga, K.; Myers, O.M.; Ermis-Demirtas, H.; Bloom, Z.D. The transactional theory of stress and coping as a stress management model for students in Hispanic-serving universities. J. Am. Coll. Health 2025, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, J.J. Emotion Regulation: Current Status and Future Prospects. Psychol. Inq. 2015, 26, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brady, S.T.; Hard, B.M.; Gross, J.J. Reappraising test anxiety increases academic performance of first-year college students. J. Educ. Psychol. 2018, 110, 395–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiesa, A.; Serretti, A.; Jakobsen, J.C. Mindfulness: Top–down or bottom–up emotion regulation strategy? Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2013, 33, 82–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, C.J.; Hooven, C. Interoceptive Awareness Skills for Emotion Regulation: Theory and Approach of Mindful Awareness in Body-Oriented Therapy (MABT). Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seth, A.K.; Tsakiris, M. Being a Beast Machine: The Somatic Basis of Selfhood. Trends. Cogn. Sci. 2018, 22, 969–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seth, A.K.; Friston, K.J. Active interoceptive inference and the emotional brain. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 2016, 371, 20160007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conley, C.S.; Durlak, J.A.; Kirsch, A.C. A Meta-analysis of Universal Mental Health Prevention Programs for Higher Education Students. Prev. Sci. 2015, 16, 487–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rith-Najarian, L.R.; Boustani, M.M.; Chorpita, B.F. A systematic review of prevention programs targeting depression, anxiety, and stress in university students. J. Affect. Disord. 2019, 257, 568–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bamber, M.D.; Schneider, J.K. Mindfulness-based meditation to decrease stress and anxiety in college students: A narrative synthesis of the research. Educ. Res. Rev. 2016, 18, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawson, A.F.; Brown, W.W.; Anderson, J.; Datta, B.; Donald, J.N.; Hong, K.; Allan, S.; Mole, T.B.; Jones, P.B.; Galante, J. Mindfulness-Based Interventions for University Students: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomised Controlled Trials. Appl. Psychol. Health Wellbeing 2020, 12, 384–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Worsley, J.D.; Pennington, A.; Corcoran, R. Supporting mental health and wellbeing of university and college students: A systematic review of review-level evidence of interventions. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0266725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winter, E.L.; deLeyer-Tiarks, J.; Bellara, A.P.; Bray, M.A.; Schreiber, S. Mind–Body Health in Crisis: A Survey of How Students Cared for Themselves Amidst the COVID-19 Pandemic. COVID 2024, 4, 1818–1832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flammild, M.H.; Frausing, K.P. Forankret og forbundet: Grounding i psykomotorisk praksis. In Grounding: Kropslig Forankring i Professionerne; Réol, L., Wiegaard, L., Eds.; Gad: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2024; pp. 157–177. ISBN 9788712074458. [Google Scholar]

- Ogden, P.; Fischer, J. Sensorimotor Psychotherapy: Interventions for Trauma and Attachment; W.W. Norton & Company: New York, NY, USA, 2015; ISBN 978-0-393-70613-0. [Google Scholar]

- WHO Regional Office for Europe. Wellbeing Measures in Primary Health Care/the DepCare Project: Report on a WHO Meeting; World Health Organization: Stockholm, Sweden, 1998; Available online: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/349766/WHO-EURO-1998-4234-43993-62027-eng.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 27 July 2025).

- Topp, C.W.; Østergaard, S.D.; Søndergaard, S.; Bech, P. The WHO-5 Well-Being Index: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Psychother. Psychosom. 2015, 84, 167–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eskildsen, A.; Dalgaard, V.L.; Nielsen, K.J.; Andersen, J.H.; Zachariae, R.; Olsen, L.R.; Jørgensen, A.; Christiansen, D.H. Cross-cultural adaptation and validation of the Danish consensus version of the 10-item Perceived Stress Scale. Scand. J. Work Environ. Health 2015, 41, 486–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friis, K.; Jensen, M.M.; Pedersen, M.H.; Lasgaard, M.; Larsen, F.B.; Jørgensen, S.S.; Frandsen, K.T.; Sørensen, J.B. Hvordan har du det? 2021: Sundhedsprofil for Region og Kommuner. Bind 2. Udviklingen 2010–2013–2017–2021; DEFACTUM: Aarhus, Denmark, 2022; ISBN 978-87-93657-30-4. [Google Scholar]

- Christensen, A.V.; Dixon, J.K.; Juel, K.; Ekholm, O.; Rasmussen, T.B.; Borregaard, B.; Mols, R.E.; Thrysøe, L.; Thorup, C.B.; Berg, S.K. Psychometric properties of the Danish Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale in patients with cardiac disease: Results from the DenHeart survey. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2020, 18, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Medical Association. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Participants. JAMA 2025, 333, 71–74. [CrossRef]

- Storrie, K.; Ahern, K.; Tuckett, A. A systematic review: Students with mental health problems—A growing problem. Int. J. Nurs. Pract. 2010, 16, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djernis, D.; O’Toole, M.S.; Fjorback, L.O.; Svenningsen, H.; Mehlsen, M.Y.; Stigsdotter, U.K.; Dahlgaard, J. A Short Mindfulness Retreat for Students to Reduce Stress and Promote Self-Compassion: Pilot Randomised Controlled Trial Exploring Both an Indoor and a Natural Outdoor Retreat Setting. Healthcare 2021, 9, 910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, F.; Blank, L.; Cantrell, A.; Baxter, S.; Blackmore, C.; Dixon, J.; Goyder, E. Factors that influence mental health of university and college students in the UK: A systematic review. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 1778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chernomas, W.M.; Shapiro, C. Stress, Depression, and Anxiety among Undergraduate Nursing Students. Int. J. Nurs. Educ. Scholarsh. 2013, 10, 255–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bork, S.J.; Mondisa, J. Engineering graduate students’ mental health: A scoping literature review. J. Eng. Educ. 2022, 111, 665–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, K.A.; Singh, M.; Bernard, A.; Merianos, A.L.; Vidourek, R.A. Employing the Health Belief Model to Examine Stress Management Among College Students. Am. J. Health Stud. 2012, 27, 192–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusufov, M.; Nicoloro-SantaBarbara, J.; Grey, N.E.; Moyer, A.; Lobel, M. Meta-analytic evaluation of stress reduction interventions for undergraduate and graduate students. Int. J. Stress Manag. 2019, 26, 132–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cozzolino, M.; Girelli, L.; Vivo, D.R.; Limone, P.; Celia, G. A mind-body intervention for stress reduction as an adjunct to an information session on stress management in university students. Brain Behav. 2020, 10, e01651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blanck, P.; Perleth, S.; Heidenreich, T.; Kröger, P.; Ditzen, B.; Hents, H.; Mander, J. Effects of mindfulness exercises as stand-alone intervention on symptoms of anxiety and depression: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Behav. Res. Ther. 2018, 102, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bentley, T.G.K.; D’Andrea-Penna, G.; Rakic, M.; Arce, N.; LaFaille, M.; Berman, R.; Cooley, K.; Sprimont, P. Breathing Practices for Stress and Anxiety Reduction: Conceptual Framework of Implementation Guidelines Based on a Systematic Review of the Published Literature. Brain Sci. 2023, 13, 1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, H.; Ryu, S.; Noh, J.; Lee, J. The Effectiveness of Daily Mindful Breathing Practices on Test Anxiety of Students. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0164822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fincham, G.W.; Strauss, C.; Montero-Marin, J.; Cavanagh, K. Effect of breathwork on stress and mental health: A meta-analysis of randomised-controlled trials. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.; Lau, H.B.; Chan, M.S. Coping flexibility and psychological adjustment to stressful life changes: A meta-analytic review. Psychol. Bull. 2014, 140, 1582–1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldwin, C.R.; Schertz, K.E.; Orvell, A.; Costello, C.; Takahashi, S.; Moser, J.S.; Ayduk, O.; Kross, E. Managing emotions in everyday life: Why a toolbox of strategies matters. Emotion 2025, 25, 1122–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heffer, T.; Willoughby, T. A count of coping strategies: A longitudinal study investigating an alternative method to understanding coping and adjustment. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0186057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehling, W.E.; Price, C.; Daubenmier, J.J.; Acree, M.; Bartmess, E.; Stewart, A. The Multidimensional Assessment of Interoceptive Awareness (MAIA). PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e48230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lang, C.; Feldmeth, A.K.; Brand, S.; Holsboer-Trachsler, E.; Pühse, U.; Gerber, M. Effects of a physical education-based coping training on adolescents’ coping skills, stress perceptions and quality of sleep. Phys. Educ. Sport Pedagog. 2016, 22, 213–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vancampfort, D.; Brunner, E.; van Damme, T.; Stubbs, B. Efficacy of basic body awareness therapy on functional outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Physiother. Res. Int. 2023, 28, e1975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frausing, K.P. Grounding: En indføring i begrebet. In Grounding: Kropslig Forankring i Professionerne; Réol, L., Wiegaard, L., Eds.; Gad: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2024; pp. 27–51. ISBN 9788712074458. [Google Scholar]

- Gestsdottir, S.; Lewin-Bizan, S.; von Eye, A.; Lerner, J.V.; Lerner, R.M. The structure and function of selection, optimization, and compensation in middle adolescence: Theoretical and applied implications. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 2009, 30, 585–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| n (Total = 152) | % | Mean (SD) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| WHO-5 0–35 36–50 50+ NA | 14 32 103 3 | 9.2 21.1 67.8 2.0 | 56.7 (15.9) |

| PSS 0–12 13–17 18+ NA | 44 32 70 6 | 28.9 21.1 46.1 4.0 | 17.0 (7.04) |

| HADS-A 0–7 8–10 11+ NA | 69 45 32 6 | 45.4 29.6 21.1 4.0 | 8.00 (3.73) |

| Type of Exercise Used | Use M (SD) | Helpfulness M (SD) | Perceived Barriers’ Sum |

|---|---|---|---|

| Breathing | 3.7 (1.0) | 3.6 (0.6) | 72 |

| Grounding | 3.4 (1.1) | 3.4 (0.7) | 73 |

| Relaxation | 3.2 (1.2) | 3.0 (0.8) | 94 |

| Body scan | 3.0 (1.2) | 3.0 (0.8) | 89 |

| High-pulse exercises | 2.9 (1.2) | 3.2 (0.9) | 97 |

| Awareness | 2.9 (1.3) | 3.1 (0.8) | 96 |

| Tactile stimulation | 2.8 (1.2) | 3.1 (0.8) | 78 |

| Basic psychomotor exercises | 2.8 (1.1) | 2.8 (0.9) | 85 |

| Boundary exercises | 2.7 (1.3) | 3.2 (0.8) | 82 |

| Centering | 2.7 (1.3) | 3.1 (0.8) | 98 |

| Visualization | 2.5 (1.2) | 2.9 (0.9) | 104 |

| Increasing muscle tension | 2.3 (1.2) | 2.8 (0.9) | 108 |

| Bodily resistance exercises | 1.7 (0.9) | 2.8 (0.8) | 116 |

| Perceived Barrier | Times Mentioned in the High-Risk Group (N = 61 Participants) | Times Mentioned in the Low-Risk Group (N = 66 Participants) | Chi-Square Test | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Do not know these exercises | 76 | 83 | χ2 = 0.003 df = 1 | p = 0.953 |

| Not capable enough | 95 | 59 | χ2 = 11.5 df = 1 | p < 0.001 * |

| Do not believe in effect of these exercises | 38 | 37 | χ2 = 0.209 df = 1 | p = 0.648 |

| Too troublesome or time-consuming | 106 | 66 | χ2 = 12.7 df = 1 | p < 0.001 * |

| Do not think about it in the situation | 211 | 185 | χ2 = 4.37 df = 1 | p = 0.037 * |

| Satisfied with other coping strategies | 38 | 83 | χ2 = 13.4 df = 1 | p < 0.001 * |

| Other | 65 | 50 | χ2 = 3.32 df = 1 | p = 0.068 |

| No barriers | 280 | 355 | χ2 = 3.94 df = 1 | p = 0.047 * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Frausing, K.P.; Flammild, M.H.; Dahlgaard, J. Mind–Body Practices for Mental Health in Higher Education: Breathing, Grounding, and Consistency Are Essential for Stress and Anxiety Management. Healthcare 2025, 13, 2049. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13162049

Frausing KP, Flammild MH, Dahlgaard J. Mind–Body Practices for Mental Health in Higher Education: Breathing, Grounding, and Consistency Are Essential for Stress and Anxiety Management. Healthcare. 2025; 13(16):2049. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13162049

Chicago/Turabian StyleFrausing, Kristian Park, Manja Harsted Flammild, and Jesper Dahlgaard. 2025. "Mind–Body Practices for Mental Health in Higher Education: Breathing, Grounding, and Consistency Are Essential for Stress and Anxiety Management" Healthcare 13, no. 16: 2049. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13162049

APA StyleFrausing, K. P., Flammild, M. H., & Dahlgaard, J. (2025). Mind–Body Practices for Mental Health in Higher Education: Breathing, Grounding, and Consistency Are Essential for Stress and Anxiety Management. Healthcare, 13(16), 2049. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13162049

_MD__MPH_PhD.png)