When Age Matters: How Regulatory Emotional Self-Efficacy in Managing Negative Emotions Can Mitigate the Effects of Emotional Inertia for Younger Workers

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Emotional Inertia

1.2. Buffering the Negative Effect of Emotional Inertia

1.3. The Role of Age in Affective Experiences

1.4. The Present Study

2. Method

2.1. Sample

2.2. Design and Procedure

2.3. Measures

2.4. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

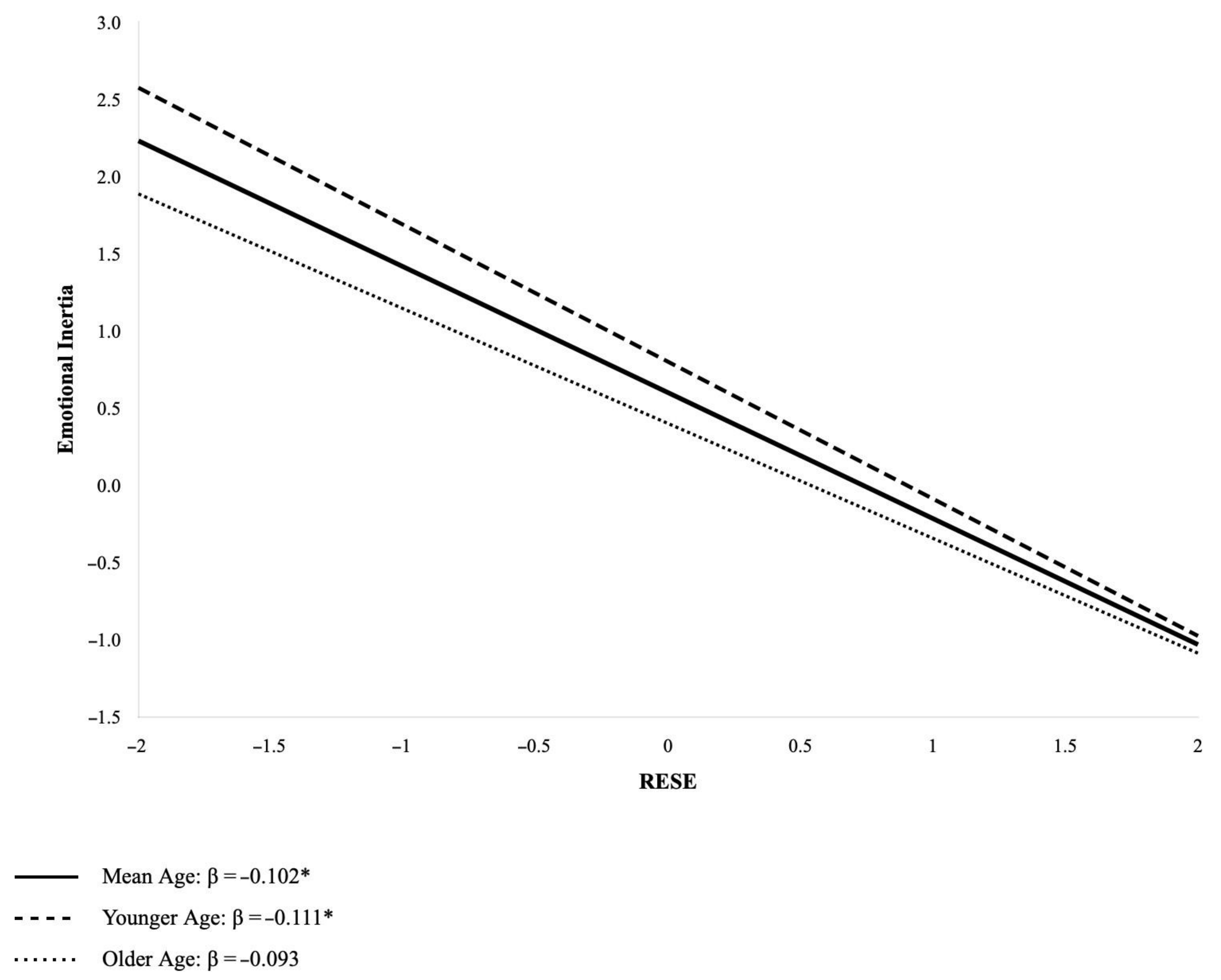

3.2. Moderation Model

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Muñoz de Bustillo, R.; Fernández-Macías, E.; Antón, J.-I.; Esteve, F. Measuring More Than Money: The Social Economics of Job Quality; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elfenbein, H.A. Emotion in organizations: Theory and research. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2023, 74, 489–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frijda, N.H. The Emotions; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Frijda, N.H. The laws of emotion. Am. Psychol. 1988, 43, 349–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weiss, H.M.; Cropanzano, R. Affective events theory. In Research in Organizational Behavior; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1996; Volume 18, pp. 1–74. [Google Scholar]

- Barsade, S.G.; Gibson, D.E. Why does affect matter in organizations? Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2007, 21, 36–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basch, J.; Fisher, C.D. Affective job events-emotions matrix: A classification of job related events and emotions experienced in the workplace. In Emotions in the Workplace: Research, Theory Andpractice; Ashkanasy, N.M., Härtel, C.E.J., Zerbe, W.J., Eds.; Quorum Books: California, CA, USA, 2000; pp. 36–48. [Google Scholar]

- Grandey, A.A.; Gabriel, A.S. Emotional labor at a crossroads: Where do we go from here? Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2015, 2, 323–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Knippenberg, D.; Van Kleef, G.A. Leadership and affect: Moving the hearts and minds of followers. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2016, 10, 799–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuppens, P.; Oravecz, Z.; Tuerlinckx, F. Feelings change: Accounting for individual differences in the temporal dynamics of affect. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2010, 99, 1042–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koval, P.; Kuppens, P. Changing feelings: Individual differences in emotional inertia. In Change in Emotion and Mental Health; Samson, A.C., Sander, D., Kramer, U., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2024; pp. 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulakos, E.D.; Arad, S.; Donovan, M.A.; Plamondon, K.E. Adaptability in the workplace: Development of a taxonomy of adaptive performance. J. Appl. Psychol. 2000, 85, 612–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, J.J.; John, O.P. Individual differences in two emotion regulation processes: Implications for affect, relationships, and well-being. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2003, 85, 348–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alessandri, G.; De Longis, E.; Eisenberg, N.; Hobfoll, S.E. A multilevel moderated mediational model of the daily relationships between hassles, exhaustion, ego-resiliency and resulting emotional inertia. J. Res. Personal. 2020, 85, 103913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wichers, M.; Wigman, J.T.W.; Myin-Germeys, I. Micro-level affect dynamics in psychopathology viewed from com-plex dynamical system theory. Emot. Rev. 2015, 7, 362–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. Self-Efficacy: The Exercise of Control; W.H. Freeman: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Alessandri, G.; Tavolucci, S.; Perinelli, E.; Eisenberg, N.; Golfieri, F.; Caprara, G.V.; Crocetti, E. Regulatory emotional self-efficacy beliefs matter for(mal) adjustment: A meta-analysis. Curr. Psychol. 2023, 42, 31004–31023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirtaş, A.S. Cognitive flexibility and mental well-being in Turkish adolescents: The mediating role of academic, social and emotional self-efficacy. An. Psicol./Ann. Psychol. 2020, 36, 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cepale, G.; Alessandri, G.; Borgogni, L.; Perinelli, E.; Avanzi, L.; Livi, S.; Coscarelli, A. Emotional efficacy beliefs at work and turnover intentions: The mediational role of organizational socialization and identification. J. Career Assess. 2021, 29, 442–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuppens, P.; Allen, N.B.; Sheeber, L.B. Emotional inertia and psychological maladjustment. Psychol. Sci. 2010, 21, 984–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Longis, E.; Alessandri, G.; Ottaviani, C. Inertia of emotions and inertia of the heart: Physiological processes underlying inertia of negative emotions at work. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 2020, 155, 210–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carstensen, L.L.; Pasupathi, M.; Mayr, U.; Nesselroade, J.R. Emotional experience in everyday life across the adult life span. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2000, 79, 644–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charles, S.T.; Carstensen, L.L. Emotion regulation and aging. In Handbook of Emotion Regulation; Gross, J.J., Ed.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2007; pp. 307–327. [Google Scholar]

- Carstensen, L.L. Social and emotional patterns in adulthood: Support for socioemotional selectivity theory. Psychol. Aging 1992, 7, 331–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carstensen, L.L. Socioemotional selectivity theory: The role of perceived endings in human motivation. Gerontologist 2021, 61, 1188–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Löckenhoff, C.E.; Carstensen, L.L. Socioemotional selectivity theory, aging, and health: The increasingly delicate balance between regulating emotions and making tough choices. J. Personal. 2004, 72, 1395–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truxillo, D.M.; Cadiz, D.M.; Hammer, L.B. Supporting the aging workforce: A review and recommendations for workplace intervention research. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2015, 2, 351–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheibe, S.; Kooij, D. Workplace aging: Reciprocal relationships between adult development and work. Annu. Rev. Dev. Psychol. 2024, 6, 479–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koval, P.; Kuppens, P.; Allen, N.B.; Sheeber, L. Getting stuck in depression: The roles of rumination and emotional inertia. Cogn. Emot. 2012, 26, 1412–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamaker, E.L. Why researchers should think “within-person”: A paradigmatic rationale. In Handbook of Research Methods for Studying Daily Life; Mehl, M.R., Conner, T.S., Eds.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 43–61. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.P.; Hamaker, E.; Bergeman, C. Investigating inter-individual differences in short-term intra-individual variability. Psychol. Methods 2012, 17, 567–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Longis, E.; Alessandri, G.; Sonnentag, S.; Kuppens, P. Inertia of negative emotions at work: Correlates of inflexible emotion dynamics in the workplace. Appl. Psychol. 2022, 71, 380–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Costa, P.L. Chronic job burnout and daily functioning: A theoretical analysis. Burn. Res. 2014, 1, 112–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E. Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. Am. Psychol. 1989, 44, 513–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohly, S.; Schmitt, A. What makes us enthusiastic, angry, feeling at rest or worried? Development and validation of an affective work events taxonomy using concept mapping methodology. J. Bus. Psychol. 2015, 30, 15–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pool, L.D.; Qualter, P. Improving emotional intelligence and emotional self-efficacy through a teaching intervention for university students. Learn. Individ. Differ. 2012, 22, 306–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirk, B.A.; Schutte, N.S.; Hine, D.W. The effect of an expressive-writing intervention for employees on emotional self-efficacy, emotional intelligence, affect, and workplace incivility. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2011, 41, 179–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Social cognitive theory: An agentic perspective. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2001, 52, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caprara, G.V.; Caprara, M.; Steca, P. Personality’s correlates of adult development and aging. Eur. Psychol. 2003, 8, 131–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A.; Caprara, G.V.; Barbaranelli, C.; Gerbino, M.; Pastorelli, C. Role of affective self-regulatory efficacy in diverse spheres of psychosocial functioning. Child Dev. 2003, 74, 769–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caprara, G.V.; Steca, P. The contribution of self–regulatory efficacy beliefs in managing affect and family relationships to positive thinking and hedonic balance. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 2006, 25, 603–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alessandri, G.; Caprara, G.V.; Eisenberg, N.; Steca, P. Reciprocal relations among self-efficacy beliefs and prosociality across time. J. Personal. 2009, 77, 1229–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caprara, G.; Vecchione, M.; Barbaranelli, C.; Alessandri, G. Emotional stability and affective self-regulatory efficacy beliefs: Proofs of integration between trait theory and social cognitive theory. Eur. J. Personal. 2013, 27, 145–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alessandri, G.; Perinelli, E.; De Longis, E.; Schaufeli, W.B.; Theodorou, A.; Borgogni, L.; Caprara, G.V.; Cinque, L. Job 650 burnout: The contribution of emotional stability and emotional self-efficacy beliefs. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2018, 91, 823–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, H.S.; Kern, M.L. Personality, well-being, and health. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2014, 65, 719–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotov, R.; Gamez, W.; Schmidt, F.; Watson, D. Linking “big” personality traits to anxiety, depressive, and substance use disorders: A meta-analysis. Psychol. Bull. 2010, 136, 768–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, P.T.; McCrae, R.R. Normal personality assessment in clinical practice: The NEO Personality Inventory. Psychol. Assess. 1992, 4, 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbaranelli, C.; Caprara, G.V. Measuring the Big Five in self-report and other ratings: A multitrait-multimethod study. Eur. J. Psychol. Assess. 2000, 16, 31–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alarcon, G.; Eschleman, K.J.; Bowling, N.A. Relationships between personality variables and burnout: A meta-analysis. Work. Stress 2009, 23, 244–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Van Der Zee, K.I.; Lewig, K.A.; Dollard, M.F. The relationship between the big five personality factors and burnout: A study among volunteer counselors. J. Soc. Psychol. 2006, 146, 31–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emeriau-Farges, C.V.; Deschênes, A.A.; Dussault, M. Emotional self-efficacy and psychological health of police officers. Polic. Int. J. 2019, 42, 598–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sommovigo, V.; Rosa, V.; Alfano, V.; Laudadio, A.; Borgogni, L. Aging and interpersonal strain: The role of self-efficacy and social drivers of inclusive workplaces. Soc. Sci. 2025, 14, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavolucci, S.; Alessandri, G.; Eisenberg, N.; Filosa, L.; Sommovigo, V.; Rosa, V. Regulatory Emotional Self-Efficacy in Managing Negative Emotion sat Work: A Validation Study. J. Personal. Assess. 2025, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sommovigo, V.; Tavolucci, S.; Filosa, L.; Rosa, V.; Carnevali, L.; Ottaviani, C.; Alessandri, G. Daily cortisol variations are predicted proximally by self-efficacy beliefs at work and indirectly by perceived self-regulatory abilities in managing negative emotions. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 2023, 193, 112244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joseph, D.L.; Newman, D.A. Emotional intelligence: An integrative meta-analysis and cascading model. J. Appl. Psychol. 2010, 95, 54–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flett, G.L.; Blankstein, K.R.; Obertynski, M. Affect intensity, coping styles, mood regulation expectancies, and de-pressive symptoms. Personal. Individ. Differ. 1996, 20, 221–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberg, N.; Cumberland, A.; Spinrad, T.L.; Fabes, R.A.; Shepard, S.A.; Reiser, M.; Murphy, B.C.; Losoya, S.H.; Guthrie, K. The relations of regulation and emotionality to children’s externalizing and internalizing problem behavior. Child Dev. 2001, 72, 1112–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinberg, M.K.; Tronick, E.Z.; Cohn, J.F.; Olson, K.L. Gender differences in emotional expressivity and self-regulation during early infancy. Dev. Psychol. 1999, 35, 175–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCrae, R.R.; Costa, P.T. Empirical and theoretical status of the five-factor model of personality traits. In The SAGE Handbook of Personality Theory and Assessment: Volume 1. Personality Theories and Models; Boyle, G.J., Matthews, G., Saklofske, D.H., Eds.; SAGE Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 273–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAdams, D.P. What do we know when we know a person? J. Personal. 1995, 63, 365–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graziano, W.G.; Jensen-Campbell, L.A.; Finch, J.F. The self as a mediator between personality and adjustment. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1997, 73, 392–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandura, A. Guide to construction of self-efficacy scales. In Self-Efficacy Beliefs of Adolescents; Pajares, F., Urdan, T., Eds.; Information Age: London, UK, 2006; Volume 5, pp. 307–337. [Google Scholar]

- Manfredi, L.; López-Pérez, B.; Gregori, F.; Lundie, D.; Shannon, L.; Zuffianò, A. The inertia of anger and sadness among adolescents and adults: The role of self-efficacy in regulating negative emotions. Eur. J. Personal. 2025, 39, 292–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, J.A. A circumplex model of affect. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1980, 39, 1161–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doerwald, F.; Scheibe, S.; Zacher, H.; Van Yperen, N.W. Emotional competencies across adulthood: State of knowledge and implications for the work context. Work. Aging Retire. 2016, 2, 159–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothbart, M.K.; Ahadi, S.A.; Evans, D.E. Temperament and personality: Origins and outcomes. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2000, 78, 122–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, J.J.; Carstensen, L.L.; Pasupathi, M.; Tsai, J.; Skorpen, C.G.; Hsu, A.Y.C. Emotion and aging: Experience, expression, and control. Psychol. Aging 1997, 12, 590–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bleidorn, W.; Schwaba, T.; Zheng, A.; Hopwood, C.J.; Sosa, S.S.; Roberts, B.W.; Briley, D.A. Personality stability and change: A meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Psychol. Bull. 2022, 148, 588–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolger, N. Coping as a personality process: A prospective study. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1990, 59, 525–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heppner, P.P.; Cook, S.W.; Wright, D.M.; Johnson, W.C. Progress in resolving problems: A problem-focused style of coping. J. Couns. Psychol. 1995, 42, 279–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carstensen, L.L.; Fung, H.H.; Charles, S.T. Socioemotional selectivity theory and the regulation of emotion in the second half of life. Motiv. Emot. 2003, 27, 103–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.J.; Markides, K.S. Activity and mortality among aged persons over an eight-year period. J. Gerontol. 1990, 45, S39–S42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charles, S.T.; Reynolds, C.A.; GaÜ, M. Age-related differences and change in positive and negative affect over 23 years. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2001, 80, 136–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urry, H.L.; Gross, J.J. Emotion regulation in older age. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2010, 19, 352–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, O.P.; Gross, J.J. Healthy and unhealthy emotion regulation: Personality processes, individual differences, and life span development. J. Personal. 2004, 72, 1301–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evans, D.E.; Rothbart, M.K. Developing a model for adult temperament. J. Res. Personal. 2007, 41, 868–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caprara, G.V.; Di Giunta, L.; Eisenberg, N.; Gerbino, M.; Pastorelli, C.; Tramontano, C. Assessing regulatory emotional self-efficacy in three countries. Psychol. Assess. 2008, 20, 227–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, D.; Clark, L.A.; Carey, G. Positive and negative affectivity and their relation to anxiety and depressive dis-orders. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 1988, 97, 346–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cloos, L.; Ceulemans, E.; Kuppens, P. Development, validation, and comparison of self-report measures for positive and negative affect in intensive longitudinal research. Psychol. Assess. 2023, 35, 189–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, J.A. Core affect and the psychological construction of emotion. Psychol. Rev. 2003, 110, 145–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto, C.J.; John, O.P. The next Big Five Inventory (BFI-2): Developing and assessing a hierarchical model with 15 facets to enhance bandwidth, fidelity, and predictive power. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2017, 113, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gable, S.L.; Reis, H.T.; Elliot, A.J. Behavioral activation and inhibition in everyday life. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2000, 78, 1135–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karasek, R.A. Job demands, job decision latitude, and mental strain: Implications for job redesign. Adm. Sci. Q. 1979, 24, 285–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamantopoulos, A.; Winklhofer, H.M. Index construction with formative indicators: An alternative to scale development. J. Mark. Res. 2001, 38, 269–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, J.C.; Bernstein, I.H. Psychometric Theory, 3rd ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Asparouhov, T.; Hamaker, E.L.; Muthén, B. Dynamic structural equation models. Struct. Equ. Model. Multidiscip. J. 2018, 25, 359–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamaker, E.L.; Wichers, M. No time like the present: Discovering the hidden dynamics in intensive longitudinal data. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2017, 26, 10–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamaker, E.L.; Asparouhov, T.; Brose, A.; Schmiedek, F.; Muthén, B. At the frontiers of modeling intensive longitudinal data: Dynamic structural equation models for the affective measurements from the COGITO study. Multivar. Behav. Res. 2018, 53, 820–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamaker, E.L.; Kuiper, R.M.; Grasman, R.P.P.P. A critique of the cross-lagged panel model. Psychol. Methods 2015, 20, 102–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nickell, S. Biases in dynamic models with fixed effects. Econom. J. Econom. Soc. 1981, 49, 1417–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNeish, D.; Hamaker, E.L. A primer on two-level dynamic structural equation models for intensive longitudinal data in Mplus. Psychol. Methods 2020, 25, 610–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthén, L.K.; Muthén, B.O. Mplus User’s Guide, 8th ed.; Muthén & Muthén: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- McNeish, D.; MacKinnon, D.P. Intensive longitudinal mediation in Mplus. Psychol. Methods 2023, 28, 449–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; MacKinnon, D.P. Bayesian mediation analysis. Psychol. Methods 2009, 14, 301–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelman, A.; Carlin, J.B.; Stern, H.S.; Dunson, D.B.; Vehtari, A.; Rubin, D.B. Bayesian Data Analysis, 3rd ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lodder, G.M.; Van Halem, S.; Bülow, A.; van Scheppingen, M.A.; Weller, J.; ReiÜ, A.K. Daily fluctuations in occupation with and worry about COVID-19. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2021, 182, 111078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gelman, A.; Rubin, D.B. Inference from iterative simulation using multiple sequences. Stat. Sci. 1992, 7, 457–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, S.P.; Gelman, A. General methods for monitoring convergence of iterative simulations. J. Comput. Graph. Stat. 1998, 7, 434–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baltes, P.B.; Baltes, M.M. Psychological perspectives on successful aging: The model of selective optimization with compensation. In Successful Aging: Perspectives from the Behavioral Sciences; Baltes, P.B., Baltes, M.M., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1990; pp. 1–34. [Google Scholar]

- Freund, A.M. Age-differential motivational consequences of optimization versus compensation focus in younger and older adults. Psychol. Aging 2006, 21, 240–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ebner, N.C.; Freund, A.M.; Baltes, P.B. Developmental changes in personal goal orientation from young to late adulthood: From striving for gains to maintenance and prevention of losses. Psychol. Aging 2006, 21, 664–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanfer, R.; Ackerman, P.L. Aging, adult development, and work motivation. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2004, 29, 440–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carstensen, L.L.; Gross, J.J.; Fung, H.H. The social context of emotional experience. In Annual Review of Gerontology and Geriatrics: Vol. 17. Focus on Emotion and Adult Development; Schaie, K.W., Lawton, M.P., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1998; pp. 325–352. [Google Scholar]

- Sardella, A.; Lenzo, V.; Basile, G.; Martino, G.; Quattropani, M.C. Emotion regulation strategies and difficulties in older adults: A systematic review. Clin. Gerontol. 2023, 46, 280–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De France, K.; Hollenstein, T. Emotion regulation and relations to well-being across the lifespan. Dev. Psychol. 2019, 55, 1768–1774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldao, A.; Jazaieri, H.; Goldin, P.R.; Gross, J.J. Adaptive and maladaptive emotion regulation strategies: Interactive effectsduring CBT for social anxiety disorder. J. Anxiety Disord. 2014, 28, 382–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldao, A.; Nolen-Hoeksema, S.; Schweizer, S. Emotion-regulation strategies across psychopathology: A meta-analytic review. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2010, 30, 217–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, J.J. Emotion regulation: Affective, cognitive, and social consequences. Psychophysiology 2002, 39, 281–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nowlan, J.S.; Wuthrich, V.M.; Rapee, R.M. Positive reappraisal in older adults: A systematic literature review. Aging Ment. Health 2015, 19, 475–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Favaretto, E.; Bedani, F.; Brancati, G.E.; De Berardis, D.; Giovannini, S.; Scarcella, L.; Sette, S.; Pampaloni, I.; Perugi, G.; Pini, G.E.; et al. Synthesising 30 years of clinical experience and scientific insight on affective temperaments in psychiatric disorders: State of the art. J. Affective Disord. 2024, 362, 406–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothbart, M.K.; Rueda, M.R. The development of effortful control. In Devel-Oping Individuality in the Human Brain: A Tribute to Michael I. Posner; Mayr, U., Awh, E., Keele, S.W., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2005; pp. 167–188. [Google Scholar]

- Qiao, Y.; Fan, P.; Li, F.; Chen, T. Learning and adaptation of transformational leaders: Linking transformational leadership to leader self-efficacy for emotional regulation and work engagement. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2025, 98, e70016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleiman, E.M.; Rizvi, S.L.; Duberstein, P.R. Initial validation of an ecological momentary assessment measure of self-efficacy to manage negative emotions. Assessment 2023, 30, 2223–2233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuffianò, A.; Sette, S.; Manfredi, L.; Gregori, F.; Lopéz-Pérez, B.; Polias, S.; Marti-Vilar, M.; Di Giusto Valle, C.; Benito-Ambrona, T.; Pastorelli, C. The relation between self-esteem and regulatory emotional self-efficacy in daily life: A study among university students. Identity 2023, 23, 36–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doty, D.H.; Glick, W.H. Common methods bias: Does common methods variance really bias results? Organ. Res. Methods 1998, 1, 374–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conway, J.M.; Lance, C.E. What reviewers should expect from authors regarding common method bias in organizational research. J. Bus. Psychol. 2010, 25, 325–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koval, P.; Kuppens, P. Changing emotion dynamics: Individual differences in the effect of anticipatory social stress on emotional inertia. Emotion 2012, 12, 256–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delhom, I.; Satorres, E.; Meléndez, J.C. Emotional intelligence intervention in older adults to improve adaptation and reduce negative mood. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2022, 34, 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Splevins, K.; Smith, A.; Simpson, J. Do improvements in emotional distress correlate with becoming more mindful? A study of older adults. Aging Ment. Health 2009, 13, 328–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. SEX | 1 | — | — | — | — | — |

| 2. AGE | 0.087 | 1 | — | — | — | — |

| 3. RESE | −0.073 | 0.076 | 1 | — | — | — |

| 4. NEUR | 0.132 | −0.195 * | −0.564 *** | 1 | — | — |

| 5. JD | −0.038 | −0.100 | 0.049 | 0.006 | 1 | 0.128 *** |

| 6. NEG | 0.098 | −0.247 ** | −0.315 *** | 0.491 *** | 0.194 * | 1 |

| Mean | — | 45.809 | 3.318 | 2.884 | 0.458 | 22.894 |

| SD | — | 12.605 | 0.614 | 0.638 | 0.720 | 19.753 |

| ICC1 | — | — | — | — | 0.368 *** | 0.682 *** |

| ICC2 | — | — | — | — | 0.945 *** | 0.984 *** |

| Parameters | Standardized Estimates | 95% CI Lower | 95% CI Upper | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Within-level | |||||

| NEGt−1 | → | NEGt | 0.259 | 0.220 | 0.294 |

| JD | → | NEGt | 0.122 | 0.096 | 0.146 |

| Between-level | |||||

| RESE | → | φNEG | −0.266 | −0.475 | −0.001 |

| RESExAGE | → | φNEG | 0.509 | 0.127 | 0.731 |

| AGE | → | φNEG | −0.158 | −0.343 | 0.088 |

| SEX | → | φNEG | 0.003 | −0.209 | 0.219 |

| NEUR | → | φNEG | −0.141 | −0.361 | 0.117 |

| JD | → | φNEG | −0.118 | −0.315 | 0.067 |

| μNEG | → | φNEG | 0.054 | −0.156 | 0.263 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tavolucci, S.; Filosa, L.; Sommovigo, V.; Rosa, V.; Alivernini, F.; Baiocco, R.; Borghi, A.; Chirico, A.; Fini, C.; Palombi, T.; et al. When Age Matters: How Regulatory Emotional Self-Efficacy in Managing Negative Emotions Can Mitigate the Effects of Emotional Inertia for Younger Workers. Healthcare 2025, 13, 2047. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13162047

Tavolucci S, Filosa L, Sommovigo V, Rosa V, Alivernini F, Baiocco R, Borghi A, Chirico A, Fini C, Palombi T, et al. When Age Matters: How Regulatory Emotional Self-Efficacy in Managing Negative Emotions Can Mitigate the Effects of Emotional Inertia for Younger Workers. Healthcare. 2025; 13(16):2047. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13162047

Chicago/Turabian StyleTavolucci, Simone, Lorenzo Filosa, Valentina Sommovigo, Valentina Rosa, Fabio Alivernini, Roberto Baiocco, Anna Borghi, Andrea Chirico, Chiara Fini, Tommaso Palombi, and et al. 2025. "When Age Matters: How Regulatory Emotional Self-Efficacy in Managing Negative Emotions Can Mitigate the Effects of Emotional Inertia for Younger Workers" Healthcare 13, no. 16: 2047. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13162047

APA StyleTavolucci, S., Filosa, L., Sommovigo, V., Rosa, V., Alivernini, F., Baiocco, R., Borghi, A., Chirico, A., Fini, C., Palombi, T., Pistella, J., Lucidi, F., & Alessandri, G. (2025). When Age Matters: How Regulatory Emotional Self-Efficacy in Managing Negative Emotions Can Mitigate the Effects of Emotional Inertia for Younger Workers. Healthcare, 13(16), 2047. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13162047