Resilience and Mobbing Among Nurses in Emergency Departments: A Cross-Sectional Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Literature Review

1.2. Mobbing, Mental Resilience, and WHOQOL-BREF Among Nursing Staff in Emergency Departments

1.3. Mental Resilience as a Protective Factor

1.4. WHOQOL-BREF Implications

1.5. Significance and Importance of the Study

- Strengthening psychological resilience;

- Fostering a greater sense of purpose and professional identity;

1.6. Scope and Aims of the Research

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Place of Conduct

- High volume of emergency admissions, ensuring exposure to high-stress clinical environments.

- Presence of full-time ED nursing staff, ensuring consistency in participants’ work settings.

- Institutional willingness to participate, including administrative approval and ethical clearance.

- Variability in organizational structure and culture, allowing for a broader representation of workplace conditions.

2.3. Study Population

2.4. Study Instruments

2.4.1. Workplace Psychological Violence Behavior (WPVB) Questionnaire

2.4.2. WHOQOL-BREF

2.4.3. Connor–Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC)

2.5. Data Collection Process-Research Ethics

2.6. Statistical Analysis

- The WPVB subscale scores were computed by summing the responses within each domain (range per item: 0–5), resulting in both individual domain and overall scores.

- The CD-RISC-25 total resilience score was calculated by summing the 25 items (range: 0–100), with higher values reflecting greater resilience.

- The WHOQOL-BREF domain scores were computed according to the WHO scoring manual and were transformed into a 0–100 scale, with higher scores indicating a better perceived quality of life.

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. WHOQOL-BREF and Resilience

4.2. Mobbing and WHOQOL-BREF

4.3. Resilience and Mobbing

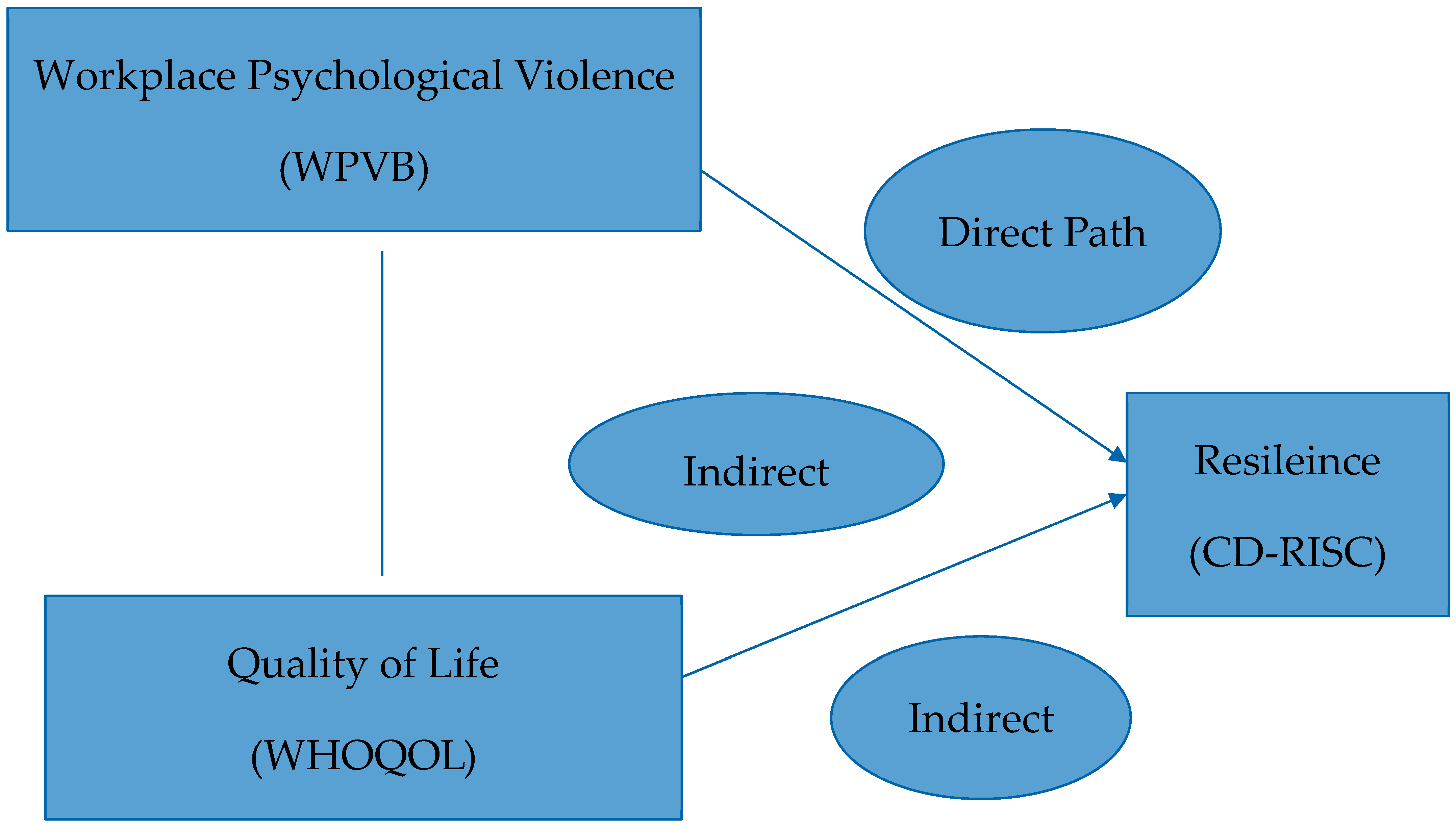

4.4. Mediating Role of Resilience

4.5. Implications for Practice and Policy

4.6. Implications and Strengths

4.7. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CD-RISC | Connor–Davidson Resilience Scale |

| DYPE | Regional Health Authority |

| ED | Emergency Department |

| ICC | Intraclass Correlation Coefficient |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| SE | Standard Error |

| SPSS | Statistical Package for the Social Sciences |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| WHOQOL-BREF | World Health Organization Quality of Life-Brief Version |

| WPVB | Workplace Psychologically Violent Behaviors Questionnaire |

| IQR | Interquartile Range |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

| β | Beta Coefficient (used in regression analysis) |

| α | Cronbach’s Alpha (internal consistency reliability) |

| ρ (rho) | Spearman’s Rank Correlation Coefficient |

| r | Pearson’s Correlation Coefficient |

| p-value | Probability Value (used to assess statistical significance) |

References

- Einarsen, S.; Hoel, H.; Zapf, D.; Cooper, C.L. Bullying and Emotional Abuse in the Workplace: International Perspectives in Research and Practice; Taylor & Francis: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Yildirim, A.; Yildirim, D. Mobbing in the workplace by peers and managers: Mobbing experienced by nurses working in healthcare facilities in Turkey and its effect on nurses. J. Clin. Nurs. 2007, 16, 1444–1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leymann, H. Mobbing and psychological terror at workplaces. Violence Vict. 1990, 5, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Einarsen, S.; Hoel, H.; Zapf, D.; Cooper, C.L. Bullying and Harassment in the Workplace: Developments in Theory, Research, and Practice, 2nd ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Zapf, D.; Einarsen, S. Bullying in the workplace: Recent trends in research and practice—An introduction. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2001, 10, 369–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Notelaers, G.; De Witte, H.; Einarsen, S. A task- and context-related stress perspective on workplace bullying. In Bullying and Harassment in the Workplace; Einarsen, S., Hoel, H., Zapf, D., Cooper, C.L., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2011; Volume 2, pp. 73–97. [Google Scholar]

- Zapf, D.; Escartín, J.; Scheppa-Lahyani, M.; Einarsen, S.; Hoel, H.; Vartia, M. Empirical findings on prevalence and risk groups of bullying in the workplace. In Bullying and Harassment in the Workplace: Developments in Theory, Research, and Practice; Einarsen, S., Hoel, H., Zapf, D., Cooper, C.L., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2011; Volume 2, pp. 73–97. [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen, M.B.; Einarsen, S. Outcomes of exposure to workplace bullying: A meta-analytic review. Work Stress 2012, 26, 309–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- General Confederation of Greek Workers (GSEE). Report on Psychological Harassment in the Workplace; General Confederation of Greek Workers: Athens, Greece, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Deligianni-Kouimtzi, V. Dignity in the Workplace and the Ethics of Resistance; Nissos Publications: Athens, Greece, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Spiridakis, M. Power and Harassment at Work; Dionikos Publications: Athens, Greece, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Bakella, P.; Giangou, E.; Brachantini, K. The influence of “mobbing syndrome” in the professional life of nurses. Hell. J. Nurs. Sci. 2013, 6, 15–21. [Google Scholar]

- Mantziou, M.; Tsiantou, H. Harassment and aggression in emergency departments: Views of health professionals. Nosileftiki (Nurs.) 2004, 43, 45–53. [Google Scholar]

- Georgiou, K.; Alexiou, M. Comparative study of mobbing incidents in public and private hospitals. Ep. Ygeias (Health Rev.) 2007, 15, 77–88. [Google Scholar]

- Nella, P.; Gouzou, M.; Kolovos, P.; Tsiou, C.; Fragkiadaki, E. Emergency department nurses and incidents of violence—Implications for management. In Proceedings of the 16th Panhellenic Conference on Health Services Management, Alexandroupolis, Greece, 14–18 April 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Sahin, B.; Cetin, M.; Cimen, M.; Yildiran, N. Assessment of turkish junior male physicians’ exposure to mobbing behavior. Croat. Med. J. 2012, 53, 357–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Efe, S.Y.; Ayaz, S. Mobbing behaviors encountered by nurses working in healthcare facilities. J. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2010, 1, 25–32. [Google Scholar]

- Çevik Akyil, R.; Tan, M.; Saritaş, S.; Altuntaş, S. Levels of mobbing perception among nurses in Eastern Turkey. Int. Nurs. Rev. 2012, 59, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pai, H.C.; Lee, S. Risk factors for workplace violence in clinical registered nurses in Taiwan. J. Clin. Nurs. 2011, 20, 1405–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, C.M.B.; Bouthillette, F.; Raboud, J.M.; Bullock, L.; Moore, C.F.; Christenson, J.M.; Grafstein, E.; Rae, S.; Ouellet, L.; Gillrie, C.; et al. Violence in the emergency department: A survey of health care workers. CMAJ 1999, 161, 1245–1248. [Google Scholar]

- Presley, D.; Robinson, G. Violence in the emergency department: Nurses contend with prevention in the health care arena. Nurs. Clin. N. Am. 2002, 37, 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyneham, J. Violence in New South Wales emergency departments. Aust. J. Adv. Nurs. 2000, 18, 8–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simons, S.R.; Mawn, B.E. Workplace bullying among nurses. J. Nurs. Care Qual. 2010, 25, 222–228. [Google Scholar]

- Yıldırım, D. Mobbing in nursing: A systematic review. Int. J. Nurs. Pract. 2009, 15, 432–442. [Google Scholar]

- Havaei, F.; MacPhee, M.; Ma, A. Workplace violence and turnover intention among emergency department nurses: The role of perceived organizational support. J. Nurs. Manag. 2020, 28, 916–924. [Google Scholar]

- Longo, J. Prevention of workplace bullying among nurses. J. Nurs. Manag. 2014, 22, 260–267. [Google Scholar]

- Kılınç, T.; Sis Çelik, A. The relationship between workplace bullying, mental resilience, and quality of life among nurses: A cross-sectional study. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2021, 30, 1005–1014. [Google Scholar]

- Hart, P.L.; Brannan, J.D.; De Chesnay, M. Resilience in nurses: An integrative review. J. Nurs. Manag. 2014, 22, 720–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mealer, M.; Jones, J.; Moss, M. A qualitative study of resilience and posttraumatic stress disorder in United States ICU nurses. Intensive Care Med. 2012, 38, 1445–1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mealer, M.; Shelton, A.; Berg, B.; Rothbaum, B.; Moss, M. Increased prevalence of post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms in critical care nurses. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2014, 175, 693–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siriwardena, N.; Brown, A.; Davies, S. Exploring the relationship between resilience, burnout and work engagement in emergency department nurses. J. Emerg. Nurs. 2018, 44, 181–188. [Google Scholar]

- Adriaenssens, J.; De Gucht, V.; Maes, S. Causes and consequences of occupational stress in emergency nurses, a longitudinal study. J. Nurs. Manag. 2012, 20, 720–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarei, E.; Abdi, A.; Ghahramanian, A. The moderating role of resilience in the relationship between workplace bullying and quality of life in emergency nurses. Nurs. Open. 2021, 8, 1674–1682. [Google Scholar]

- Polit, D.F.; Beck, C.T. Nursing Research: Generating and Assessing Evidence for Nursing Practice, 10th ed.; Wolters Kluwer: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches, 4th ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, S.; Malecha, A. The Impact of Workplace Incivility on the Work Environment, Manager Skill, and Productivity. JONA J. Nurs. Adm. 2011, 41, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ames, C. Methodological strategies for research on motivation in education. In Student Motivation, Cognition, and Learning: Essays in Honor of Wilbert J. McKeachie; Pintrich, P.R., Brown, D.R., Weinstein, C.E., Eds.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1992; pp. 261–297. [Google Scholar]

- Leiter, M.P.; Laschinger, H.K.S. Workplace bullying and burnout. J. Nurs. Manag. 2009, 17, 851–857. [Google Scholar]

- Yildirim, A.; Yildirim, D. Development and psychometric evaluation of workplace psychologically violent behaviours instrument. J. Clin. Nurs. 2007, 17, 1361–1370. [Google Scholar]

- Parahoo, K. Nursing Research: Principles, Process and Issues, 3rd ed.; Palgrave Macmillan: Basingstoke, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Koinis, A.; Velonakis, E.; Tzavara, C.; Tzavella, F.; Tziaferi, S. Psychometric properties of the workplace psychologically violent behaviors-WPVB instrument. Translation and validation in Greek health rofepssionals. AIMS Public Health 2019, 6, 79–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Connor, K.M.; Davidson, J.R. Development of a new resilience scale: The Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC). Depress. Anxiety 2003, 18, 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. WHOQOL-BREF: Introduction, Administration, Scoring and Generic Version of the Assessment: Field Trial Version, December 1996; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Ginieri-Coccossis, M.; Triantafillou, E.; Tomaras, V.; Liappas, I.A.; Christodoulou, N.G.; Papadimitriou, N.G. Quality of life in mentally ill, physically ill and healthy individuals: The validation of the Greek version of the world health organization quality of life (WHOQOL-100) questionnaire. Ann. Gen. Psychiatry 2009, 8, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- West, C.P.; Dyrbye, L.N.; Erwin, P.J.; Shanafelt, T.D. Interventions to prevent and reduce physician burnout: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 2016, 388, 2272–2281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shapiro, S.L.; Astin, J.A.; Bishop, S.R.; Cordova, M. Mindfulness-based stress reduction for health care professionals: Results from a randomized trial. Int. J. Stress Manag. 2005, 12, 164–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruotsalainen, J.H.; Verbeek, J.H.; Marine, A.; Serra, C. Preventing occupational stress in healthcare workers. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015, 4, CD002892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gishen, F.; Whitman, S.; Gill, D.; Rampton, V.; Cosker, T. Reflective practice and wellbeing: A qualitative evaluation of students’ experiences of Balint groups. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 2016, 66, e525–e531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Medical Association. World medical association declaration of Helsinki: Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. In Proceedings of the 52nd WMA General Assembly, Tokyo, Japan, 3–7 October 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A.F. Beyond baron and Kenny: Statistical mediation analysis in the new millennium. Commun. Monogr. 2009, 76, 408–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behav. Res. Methods Instrum. Comput. 2004, 36, 717–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav. Res. Methods. 2008, 40, 879–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, R.M.; Kenny, D.A. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 51, 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sobel, M.E. Asymptotic confidence intervals for indirect effects in structural equation models. Sociol. Methodol. 1982, 13, 290–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atay, N.; Sahin, G.; Buzlu, S. The relationship between psychological resilience and professional quality of life in nurses. Perspect. Psychiatr. Care. 2021, 57, 1883–1890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hjemdal, O.; Friborg, O.; Stiles, T.C.; Rosenvinge, J.H.; Martinussen, M. Resilience predicting psychiatric symptoms: A prospective study of protective factors and their role in adjustment to stressful life events. Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 2006, 13, 194–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, B.W.; Dalen, J.; Wiggins, K.; Tooley, E.; Christopher, P.; Bernard, J. The Brief Resilience Scale: Assessing the ability to bounce back. Int. J. Behav. Med. 2008, 15, 194–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Einarsen, S.; Nielsen, M.B. Workplace bullying as an antecedent of mental health problems: A five-year prospective and representative study. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 2015, 88, 131–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giorgi, G.; Mancuso, S.; Fiz Perez, F.J.; Mucci, N. Bullying and work-related stress in the nursing profession: An empirical study. La Med. Del Lav. 2016, 107, 264–272. [Google Scholar]

- Gkagkanteros, A.; Kontodimopoulos, N.; Talias, M.A. Does bullying in the hospital affect the health-related quality of life of health professionals? Work 2022, 73, 263–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vessey, J.A.; DeMarco, R.; Gaffney, D.A.; Budin, W.C. Bullying of staff registered nurses in the workplace: A preliminary study for developing personal and organizational strategies for the transformation of hostile to healthy workplace environments. J. Prof. Nurs. 2009, 25, 299–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laschinger, H.K.; Grau, A.L.; Finegan, J.; Wilk, P. New graduate nurses’ experiences of bullying and burnout in hospital settings. J. Adv. Nurs. 2010, 66, 2732–2742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rushton, C.H.; Batcheller, J.; Schroeder, K.; Donohue, P. Burnout and resilience among nurses practicing in high-intensity settings. Am. J. Crit. Care. 2015, 24, 412–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luther, L.; Cragun, D.; Barsky, A.R.; Kunik, M.E. Resilience training to reduce distress and increase empathy in emergency department personnel. J. Nurs. Manag. 2021, 29, 334–341. [Google Scholar]

- Yıldırım, D. The role of resilience in the relationship between workplace bullying and job satisfaction: A cross-sectional study among nurses. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2019, 28, 514–523. [Google Scholar]

- Karimi, Z.; Mortazavi, H.; Salehi, K. The mediating role of resilience in the relationship between workplace bullying and job satisfaction in nurses. J. Nurs. Manag. 2021, 29, 1132–1139. [Google Scholar]

- Mejia-Lancheros, C.; Woodhall-Melnik, J.; Wang, R.; Hwang, S.W.; Stergiopoulos, V.; Durbin, A. Associations of resilience with quality of life levels in adults experiencing homelessness and mental illness: A longitudinal study. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2021, 19, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maxwell, S.E.; Cole, D.A. Bias in cross-sectional analyses of longitudinal mediation. Psychol. Methods 2007, 12, 23–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado, C.; Upton, D.; Ranse, K.; Furness, T.; Foster, K. Nurses’ resilience and the emotional labour of nursing work: An integrative review of empirical literature. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2017, 70, 71–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| n = 90 | n | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 15 | 15.7 |

| Female | 75 | 84.3 | |

| Educational level | 2-year college | 6 | 6.7 |

| Technological University (4 years) | 64 | 71.1 | |

| University | 5 | 5.6 | |

| MSc | 12 | 13.3 | |

| PhD | 3 | 3.3 | |

| Family status | Single | 16 | 17.8 |

| Married | 72 | 80.0 | |

| Divorced | 2 | 2.2 | |

| Have children | No | 23 | 25.6 |

| Yes | 67 | 74.4 | |

| Number of children | 1 | 23 | 34.8 |

| 2 | 37 | 56.1 | |

| 3 | 6 | 9.1 | |

| Living | Alone | 14 | 15.6 |

| With others | 76 | 84.4 | |

| Professional | Nurse | 89 | 98.9 |

| Assistant nurse | 1 | 1.1 | |

| Health problems | 19 | 21.1 | |

| If yes, define | Heart problems | 3 | 15.8 |

| Arthritis or rheumatism | 6 | 31.6 | |

| Emphysema or chronic bronchitis | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Cataract | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Bone fracture or crack | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Leg problems | 2 | 10.5 | |

| Parkinson’s disease | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Hypertension | 3 | 15.8 | |

| Cancer | 3 | 15.8 | |

| Diabetes | 1 | 5.3 | |

| Stroke | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Chronic mental health problems | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Rectal bleeding | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Other | 2 | 10.5 | |

| Mean | SD | ||

| Age | 43.1 | 8.4 | |

| Minimum | Maximum | Mean (SD) | Median (IQR) | Cronbach’s Alpha | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall WHOQOL-BREF | 12.50 | 100.00 | 68.4 (14.49) | 75 (62.5–75) | 0.70 |

| Physical health | 27.78 | 97.22 | 65.56 (12.53) | 66.67 (58.33–75) | 0.82 |

| Psychological health | 4.17 | 91.67 | 64.31 (12.22) | 66.67 (58.33–70.83) | 0.79 |

| Social relationships | 15.00 | 90.00 | 66.56 (13.25) | 70 (60–75) | 0.74 |

| Environment | 21.88 | 81.25 | 53.76 (12.99) | 53.13 (43.75–65.63) | 0.76 |

| Resilience score (CD-RISC) | 35.00 | 100.00 | 66.38 (12.83) | 66.5 (58–74) | 0.93 |

| Attack on personality | 0.00 | 29.00 | 4.78 (6.37) | 2 (0–6) | 0.87 |

| Attack on professional | 0.00 | 28.00 | 5.74 (6.51) | 3 (1–8) | 0.86 |

| Individual’s isolation from work | 0.00 | 45.00 | 5.82 (7.61) | 4 (1–7) | 0.89 |

| Direct attack | 0.00 | 19.00 | 1.52 (3.38) | 0 (0–2) | 0.78 |

| Total WPVB score | 0.00 | 110.00 | 17.87 (21.12) | 9 (5–23) | 0.95 |

| Overall QoL | Physical Health | Psychological Health | Social Relationships | Environment | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Resilience score (CD-RISC) | r | 0.14 | 0.30 | 0.40 | 0.35 | 0.31 |

| p | 0.189 | 0.004 | <0.001 | 0.001 | 0.004 | |

| Attack on personality | rho | −0.08 | 0.03 | −0.06 | −0.02 | −0.02 |

| p | 0.436 | 0.789 | 0.585 | 0.887 | 0.886 | |

| Attack on professional | rho | −0.17 | 0.04 | −0.08 | −0.08 | −0.17 |

| p | 0.119 | 0.710 | 0.467 | 0.482 | 0.107 | |

| Individual’s isolation from work | rho | −0.01 | −0.02 | −0.06 | −0.23 | −0.33 |

| p | 0.898 | 0.817 | 0.589 | 0.030 | 0.002 | |

| Direct attack | rho | −0.06 | −0.04 | −0.18 | −0.16 | −0.30 |

| p | 0.604 | 0.679 | 0.092 | 0.137 | 0.005 | |

| Total WPVB score | rho | −0.14 | −0.02 | −0.12 | −0.12 | −0.28 |

| p | 0.205 | 0.861 | 0.271 | 0.276 | 0.008 | |

| Overall WHOQOL-BREF | Physical Health | Psychological Health | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β (SE)+ | p | β (SE)+ | p | β (SE)+ | p | |

| Gender (Females vs. Males) | 0.52 (4.22) | 0.902 | 0.15 (3.52) | 0.966 | −2.22 (2.89) | 0.443 |

| Age | −0.18 (0.19) | 0.348 | −0.02 (0.16) | 0.927 | −0.16 (0.13) | 0.231 |

| Educational level | −1.16 (1.72) | 0.505 | 1.6 (1.5) | 0.290 | 1.7 (1.23) | 0.171 |

| Married (yes vs. no) | −3.75 (5.15) | 0.469 | 0.94 (4.48) | 0.835 | −5.09 (3.67) | 0.170 |

| Have children (yes vs. no) | −1.81 (5.07) | 0.722 | −7.72 (4.39) | 0.083 | −2.85 (3.6) | 0.430 |

| Living (with others vs. alone) | 13.1 (5.48) | 0.019 | 12.41 (4.77) | 0.011 | 13.51 (3.91) | 0.001 |

| Health problems (yes vs. no) | −6.18 (3.65) | 0.095 | −1.44 (3.18) | 0.652 | 1.63 (2.6) | 0.532 |

| Resilience score (CD-RISC) | 0.13 (0.12) | 0.294 | 0.25 (0.11) | 0.023 | 0.24 (0.09) | 0.006 |

| Total WPVB score | 0.08 (0.08) | 0.341 | 0.1 (0.07) | 0.142 | 0.05 (0.06) | 0.330 |

| Social Relationships | Environment | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| β (SE)+ | p | β (SE)+ | p | |

| Gender (females vs. males) | −0.72 (3.64) | 0.845 | −2.24 (4.10) | 0.588 |

| Age | −0.09 (0.17) | 0.609 | 0.00 (0.18) | 0.994 |

| Educational level | −1.20 (1.55) | 0.441 | 2.48 (1.66) | 0.139 |

| Married (yes vs. no) | −0.78 (4.63) | 0.866 | 8.43 (5.09) | 0.102 |

| Have children (yes vs. no) | −4.29 (4.54) | 0.347 | −8.98 (4.93) | 0.073 |

| Living (with others vs. alone) | 9.43 (4.93) | 0.059 | −0.85 (5.48) | 0.877 |

| Health problems (yes vs. no) | 4.21 (3.28) | 0.204 | 4.18 (3.50) | 0.236 |

| Resilience score (CD-RISC) | 0.32 (0.11) | 0.005 | 0.27 (0.12) | 0.024 |

| Total WPVB score | 0.05 (0.07) | 0.494 | −0.01 (0.08) | 0.878 |

| Predictor Variable | Outcome Variable | Indirect Effect (95% CI) | p-Value (Indirect) | Direct Effect (95% CI) | p-Value (Direct) | Mediation Significant? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total WPVB Score | Environment | −0.053 (–0.153, 0.010) | 0.10 | −0.012 (–0.162, 0.138) | 0.87 | No |

| Direct Attack Score | Environment | −0.143 (–0.740, 0.172) | 0.37 | −0.359 (–0.740, 0.172) | 0.18 | No |

| Individual’s Isolation from Work Score | Environment | −0.124 (–0.371, 0.043) | 0.14 | −0.153 (–0.550, 0.245) | 0.44 | No |

| Individual’s Isolation from Work Score | Social Relationships | −0.148 (–0.464, 0.026) | 0.09 | 0.057 (–0.317, 0.431) | 0.76 | No |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Koinis, A.; Papathanasiou, I.V.; Moisoglou, I.; Kouroutzis, I.; Tzenetidis, V.; Anagnostopoulou, D.; Sarafis, P.; Malliarou, M. Resilience and Mobbing Among Nurses in Emergency Departments: A Cross-Sectional Study. Healthcare 2025, 13, 1908. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13151908

Koinis A, Papathanasiou IV, Moisoglou I, Kouroutzis I, Tzenetidis V, Anagnostopoulou D, Sarafis P, Malliarou M. Resilience and Mobbing Among Nurses in Emergency Departments: A Cross-Sectional Study. Healthcare. 2025; 13(15):1908. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13151908

Chicago/Turabian StyleKoinis, Aristotelis, Ioanna V. Papathanasiou, Ioannis Moisoglou, Ioannis Kouroutzis, Vasileios Tzenetidis, Dimitra Anagnostopoulou, Pavlos Sarafis, and Maria Malliarou. 2025. "Resilience and Mobbing Among Nurses in Emergency Departments: A Cross-Sectional Study" Healthcare 13, no. 15: 1908. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13151908

APA StyleKoinis, A., Papathanasiou, I. V., Moisoglou, I., Kouroutzis, I., Tzenetidis, V., Anagnostopoulou, D., Sarafis, P., & Malliarou, M. (2025). Resilience and Mobbing Among Nurses in Emergency Departments: A Cross-Sectional Study. Healthcare, 13(15), 1908. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13151908