How Do the Psychological Functions of Eating Disorder Behaviours Compare with Self-Harm? A Systematic Qualitative Evidence Synthesis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Selection Criteria

Selection Criteria Justification

2.3. Paper Selection and Data Extraction

2.4. Data Synthesis

2.5. Quality Assessment

2.6. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

3.1. Quality Assessment Results

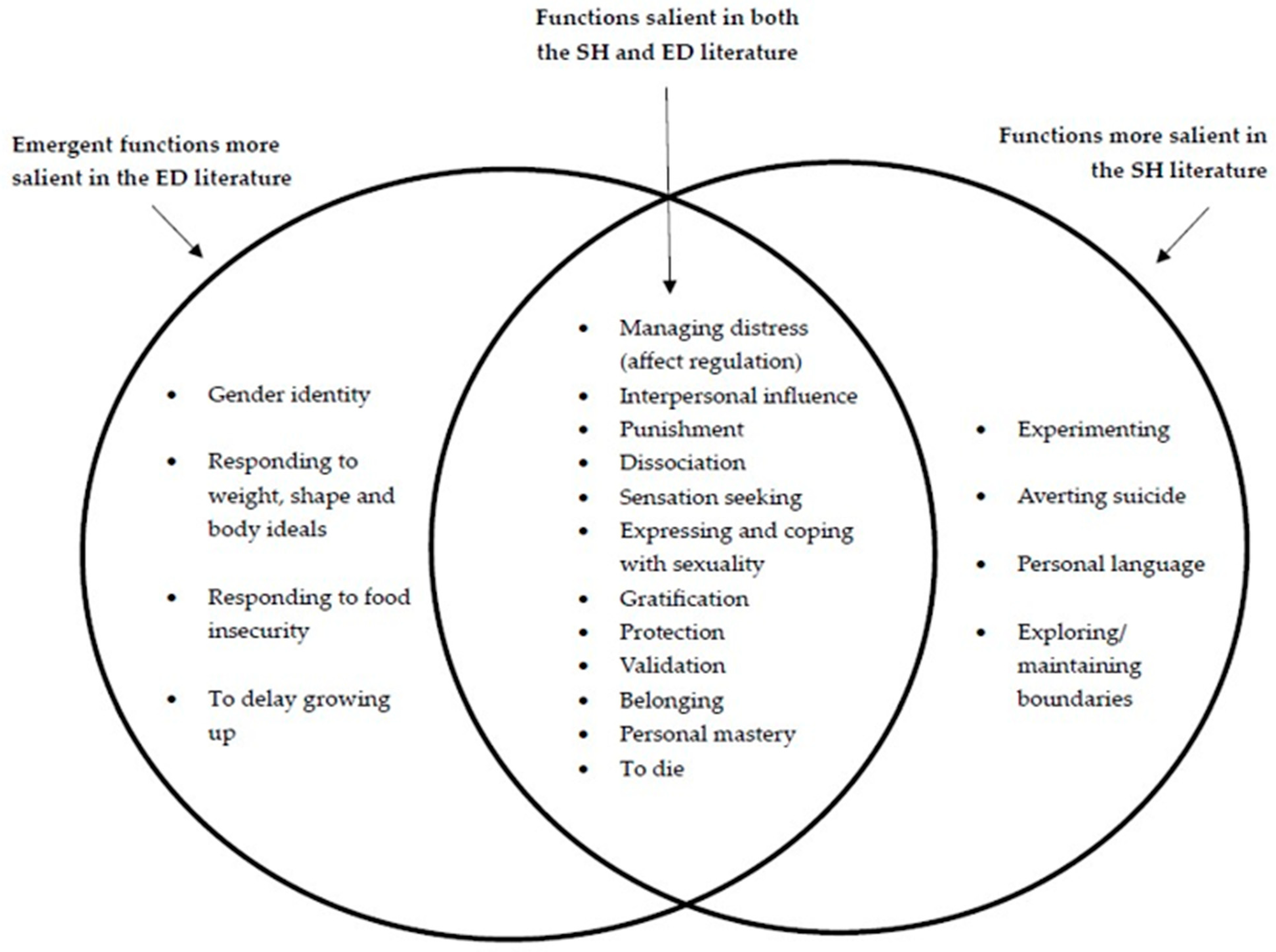

3.2. Final Framework of Reasons for ED Behaviours

- Inclusion of five new functions (to die, responding to weight, shape and body ideals, responding to food insecurity, gender identity, and to delay growing up).

- Exclusion of four functions not endorsed by the ED literature (experimenting, averting suicide, personal language, and exploring/maintaining boundaries).

- Within the function of affect regulation, replacing the subcategory ‘managing physical over emotional pain’ with ‘responding to physical sensations.’

- Addition of the subcategory ‘managing loneliness and boredom’.

- Addition of ‘positive reinforcement from others’ to the function interpersonal influence.

- ‘Taking up less space and/or disappearing’ and ‘avoiding demands of life’ as additional subcategories to the function of protection.

- Addition of subcategory ‘adhering to social norms’ to the function of belonging.

- Addition of subcategory ‘achievement/being good at something’ to the function of personal mastery.

3.3. Functions Endorsed in the ED Literature That Were Also Present in the Original SH Framework

3.3.1. Managing Distress (Affect Regulation)

3.3.2. Exerting Interpersonal Influence

3.3.3. Punishment

3.3.4. Dissociation

3.3.5. Sensation Seeking

3.3.6. Expressing and Coping with Sexuality

3.3.7. Gratification

3.3.8. Protection

3.3.9. Validation

3.3.10. Belonging

3.3.11. Personal Mastery

3.4. Emergent Functions More Salient in the ED Literature

3.4.1. To Die

3.4.2. Responding to Weight, Shape, and Body Ideals

3.4.3. Responding to Food Insecurity

3.4.4. Gender Identity

3.4.5. To Delay Growing up

3.5. Functions More Salient in the SH Literature

3.5.1. Averting Suicide

3.5.2. Maintaining or Exploring Boundaries

3.5.3. Experimenting

3.5.4. Personal Language

4. Discussion

4.1. Strengths and Limitations

4.2. Implications

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ED | Eating disorder |

| SH | Self-harm |

References

- Treasure, J.; Duarte, T.A.; Schmidt, U. Eating disorders. Lancet 2020, 395, 899–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH). Eating Disorders. Available online: https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/eating-disorders (accessed on 15 January 2025).

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Self-Harm: Assessment, Management and Preventing Recurrence. Available online: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng225 (accessed on 15 January 2025).

- Hornberger, L.L.; Lane, M.A. Identification and Management of Eating Disorders in Children and Adolescents. Pediatrics 2021, 147, e2020040279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, R.; Metcalfe, C.; Gunnell, D.J. Hospital presenting self-harm and risk of fatal and non-fatal repetition: Systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e89944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Washburn, J.J.; Potthoff, L.M.; Juzwin, K.R.; Styer, D.M. Assessing DSM-5 nonsuicidal self-injury disorder in a clinical sample. Psychol. Assess. 2015, 27, 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiekens, G.; Claes, L. Non-Suicidal Self-Injury and Eating Disordered Behaviors: An Update on What We Do and Do Not Know. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2020, 22, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warne, N.; Heron, J.; Mars, B.; Moran, P.; Stewart, A.; Munafò, M.; Biddle, L.; Skinner, A.; Gunnell, D.; Bould, H. Comorbidity of self-harm and disordered eating in young people: Evidence from a UK population-based cohort. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 282, 386–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrocas, A.L.; Holm-Denoma, J.M.; Hankin, B.L. Developmental Influences in NSSI and Eating Pathology. In Non-Suicidal Self-Injury in Eating Disorders: Advancements in Etiology and Treatment; Claes, L., Muehlenkamp, J.J., Eds.; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2014; pp. 35–53. [Google Scholar]

- Volpe, U.; Tortorella, A.; Manchia, M.; Monteleone, A.M.; Albert, U.; Monteleone, P. Eating disorders: What age at onset? Psychiatry Res. 2016, 238, 225–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cipriano, A.; Cella, S.; Cotrufo, P. Nonsuicidal Self-injury: A Systematic Review. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 1946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muehlenkamp, J.J.; Takakuni, S.; Brausch, A.M.; Peyerl, N. Behavioral functions underlying NSSI and eating disorder behaviors. J. Clin. Psychol. 2019, 75, 1219–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claes, L.; Muehlenkamp, J.J. Non-suicidal Self-Injury and Eating Disorders: Dimensions of Self-Harm. In Non-Suicidal Self-Injury in Eating Disorders: Advancements in Etiology and Treatment; Claes, L., Muehlenkamp, J.J., Eds.; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2014; pp. 3–18. [Google Scholar]

- St Germain, S.A.; Hooley, J.M. Direct and indirect forms of non-suicidal self-injury: Evidence for a distinction. Psychiatry Res. 2012, 197, 78–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Washburn, J.J.; Soto, D.; Osorio, C.A.; Slesinger, N.C. Eating disorder behaviors as a form of non-suicidal self-injury. Psychiatry Res. 2023, 319, 115002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, K.M.; Jorgensen, S.L.; Lawson, W.C.; Ohashi, Y.B.; Wang, S.B.; Fox, K.R. Comparing self-harming intentions underlying eating disordered behaviors and nonsuicidal self-injury: Replication and extension in adolescents. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2023, 56, 2200–2209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, K.R.; Wang, S.B.; Boccagno, C.; Haynos, A.F.; Kleiman, E.; Hooley, J.M. Comparing self-harming intentions underlying eating disordered behaviors and NSSI: Evidence that distinctions are less clear than assumed. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2019, 52, 564–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellison, C.; Philpot, U. Confusion between avoidant restrictive food intake disorder, restricted intake self-harm, and anorexia nervosa: Developing a primary care decision tree. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 2024, 74, 559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NHS. Restrictive Intake Self-Harm (RISH)—Practice Considerations for the Management of RISH Across Care Settings and Age. Available online: https://www.cntw.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/RISH-2025-final-copy.pdf (accessed on 20 May 2025).

- Nock, M.K. Why do People Hurt Themselves? New Insights Into the Nature and Functions of Self-Injury. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2009, 18, 78–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klonsky, E.D. The functions of deliberate self-injury: A review of the evidence. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2007, 27, 226–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suyemoto, K.L. The functions of self-mutilation. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 1998, 18, 531–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edmondson, A.; Brennan, C.; House, A. Non-suicidal reasons for self-harm: A systematic review of self-reported accounts. J. Affect. Disord. 2016, 191, 109–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McManus, F.; Waller, G. A functional analysis of binge-eating. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 1995, 15, 845–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slade, P. Towards a functional analysis of anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa. Br. J. Clin. Psychol. 1982, 21, 167–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Root, M.; Fallon, P. Treating the Victimized Bulimic: The Functions of Binge-Purge Behavior. J. Interpers. Violence 1989, 4, 90–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heatherton, T.F.; Baumeister, R.F. Binge eating as escape from self-awareness. Psychol. Bull. 1991, 110, 86–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodgers, R.F.; McLean, S.A.; Paxton, S.J. Longitudinal relationships among internalization of the media ideal, peer social comparison, and body dissatisfaction: Implications for the tripartite influence model. Dev. Psychol. 2015, 51, 706–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bardone-Cone, A.M.; Thompson, K.A.; Miller, A.J. The self and eating disorders. J. Personal. 2020, 88, 59–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kinnear, A.; Siegel, J.A.; Masson, P.C.; Bodell, L.P. Functions of disordered eating behaviors: A qualitative analysis of the lived experience and clinician perspectives. J. Eat. Disord. 2023, 11, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arcelus, J.; Haslam, M.; Farrow, C.; Meyer, C. The role of interpersonal functioning in the maintenance of eating psychopathology: A systematic review and testable model. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2013, 33, 156–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haedt-Matt, A.A.; Keel, P.K. Revisiting the affect regulation model of binge eating: A meta-analysis of studies using ecological momentary assessment. Psychol. Bull. 2011, 137, 660–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, A.; Flemming, K.; McInnes, E.; Oliver, S.; Craig, J. Enhancing transparency in reporting the synthesis of qualitative research: ENTREQ. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2012, 12, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooke, A.; Smith, D.; Booth, A. Beyond PICO: The SPIDER tool for qualitative evidence synthesis. Qual. Health Res. 2012, 22, 1435–1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smink, F.R.; van Hoeken, D.; Hoek, H.W. Epidemiology of eating disorders: Incidence, prevalence and mortality rates. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2012, 14, 406–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudson, J.I.; Hiripi, E.; Pope, H.G., Jr.; Kessler, R.C. The prevalence and correlates of eating disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Biol. Psychiatry 2007, 61, 348–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoek, H.W.; van Hoeken, D. Review of the prevalence and incidence of eating disorders. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2003, 34, 383–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchison, D.; Hay, P.; Slewa-Younan, S.; Mond, J. The changing demographic profile of eating disorder behaviors in the community. BMC Public Health 2014, 14, 943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. ICD-10: International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems: Tenth Revision; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- The EndNote Team. EndNote X9; The EndNote Team: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ouzzani, M.; Hammady, H.; Fedorowicz, Z.; Elmagarmid, A. Rayyan—A web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst. Rev. 2016, 5, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, C.; Booth, A.; Cooper, K. A worked example of “best fit” framework synthesis: A systematic review of views concerning the taking of some potential chemopreventive agents. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2011, 11, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carroll, C.; Booth, A.; Leaviss, J.; Rick, J. “Best fit” framework synthesis: Refining the method. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2013, 13, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brunton, G.; Booth, A.; Carroll, C. Chapter 9. Framework Synthesis. In Draft Version for Inclusion in: Cochrane-Campbell Handbook for Qualitative Evidence Synthesis; Noyes, J., Harden, A., Eds.; Cohrane: London, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. CASP Checklist: CASP Qualitative Studies Checklist; Critical Appraisal Skills Programme: Oxford, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Long, H.A.; French, D.P.; Brooks, J.M. Optimising the value of the critical appraisal skills programme (CASP) tool for quality appraisal in qualitative evidence synthesis. Res. Methods Med. Health Sci. 2020, 1, 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krafchek, J.; Kronborg, L. Academic emotions experienced by academically high-achieving females who developed disordered eating. Roeper Rev. A J. Gift. Educ. 2019, 41, 258–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mincey, K.A.; Hunnicutt Hollenbaugh, K.M. Exploring the Experiences of People who Engage with Pro-eating Disorder Online Media: A Qualitative Inquiry. Int. J. Adv. Couns. 2022, 44, 660–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broomfield, C.; Rhodes, P.; Touyz, S. How and why does the disease progress? A qualitative investigation of the transition into long-standing anorexia nervosa. J. Eat. Disord. 2021, 9, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rossotto, E.; Rorty-Greenfield, M.; Yager, J. What causes and maintains bulimia nervosa? Recovered and nonrecovered women’s reflections on the disorder. Eat. Disord. J. Treat. Prev. 1996, 4, 115–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, A.P.; Larkin, M.; Leung, N. The personal meaning of eating disorder symptoms. J. Health Psychol. 2011, 16, 116–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavis, A. Not eating or tasting other ways to live: A qualitative analysis of ‘living through’ and desiring to maintain anorexia. Transcult. Psychiatry 2018, 55, 454–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roer, G.E.; Solbakken, H.H.; Abebe, D.S.; Aaseth, J.O.; Bolstad, I.; Lien, L. Inpatients experiences about the impact of traumatic stress on eating behaviors: An exploratory focus group study. J. Eat. Disord. 2021, 9, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skårderud, F. Eating one’s words, part I: ‘Concretised metaphors’ and reflective function in anorexia nervosa--an interview study. Eur. Eat. Disord. Rev. J. Eat. Disord. Assoc. 2007, 15, 163–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brede, J.; Babb, C.; Jones, C.; Elliott, M.; Zanker, C.; Tchanturia, K.; Serpell, L.; Fox, J.; Mandy, W. “For me, the anorexia is just a symptom, and the cause is the autism”: Investigating restrictive eating disorders in autistic women. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2020, 50, 4280–4296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, S.; Reid, M. Understanding the experience of ambivalence in anorexia nervosa: The maintainer’s perspective. Psychol. Health 2010, 25, 551–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordbo, R.H.S.; Espeset, E.M.S.; Gulliksen, K.S.; Skarderud, F.; Holte, A. The meaning of self-starvation: Qualitative study of patients’ perception of anorexia nervosa. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2006, 39, 556–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stockford, C.; Kroese, B.S.; Beesley, A.; Leung, N. Severe and Enduring Anorexia Nervosa: The personal meaning of symptoms and treatment. Womens Stud. Int. Forum 2018, 68, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newton, M.; Boblin, S.; Brown, B.; Ciliska, D. ‘An engagement-distancing flux’: Bringing a voice to experiences with romantic relationships for women with anorexia nervosa. Eur. Eat. Disord. Rev. 2005, 13, 317–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amirapu, A.; Brady-Van den Bos, M. Disordered eating in female Indian students during the Covid-19 pandemic: The potential role of family. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2023, 56, 143–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proulx, K. Experiences of women with bulimia nervosa in a mindfulness-based eating disorder treatment group. Eat. Disord. 2008, 16, 52–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reingold, O.H.; Goldner, L. “It was wrapped in a kind of normalcy”: The lived experience and consequences in adulthood of survivors of female child sexual abuse. Child Abus. Negl. 2023, 139, 106125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindgreen, P.; Willaing, I.; Clausen, L.; Ismail, K.; Gronbæk, H.N.; Andersen, C.H.; Persson, F.; Cleal, B. “I Haven’t Told Anyone but You”: Experiences and Biopsychosocial Support Needs of People with Type 2 Diabetes and Binge Eating. Qual. Health Res. 2024, 34, 621–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, S.; Reid, M.J. ‘It’s like there are two people in my head’: A phenomenological exploration of anorexia nervosa and its relationship to the self. Psychol. Health 2012, 27, 798–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, T.L.; Williams, M.O.; Woodward, D.; Fox, J.R. The relationship between shame, perfectionism and Anorexia Nervosa: A grounded theory study. Psychol. Psychother. Theory Res. Pract. 2023, 96, 40–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eli, K. Binge eating as a meaningful experience in bulimia nervosa and anorexia nervosa: A qualitative analysis. J. Ment. Health 2015, 24, 363–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dignon, A.; Beardsmore, A.; Spain, S.; Kuan, A. ‘Why I won’t eat’: Patient testimony from 15 anorexics concerning the causes of their disorder. J. Health Psychol. 2006, 11, 942–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyons, G.; McAndrew, S.; Warne, T. Disappearing in a Female World: Men’s Experiences of Having an Eating Disorder (ED) and How It Impacts Their Lives. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 2019, 40, 557–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simone, M.; Askew, A.J.; Beccia, A.L.; Cusack, C.E.; Pisetsky, E.M. ‘Let the ladies know’: Queer women’s perceptions of how gender and sexual orientation shape their eating and weight concerns. Cult. Health Sex. 2024, 26, 108–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, R.; Malson, H. A critical exploration of lesbian perspectives on eating disorders. Psychol. Sex. 2011, 4, 62–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasson, D.H. A qualitative investigation of the relapse experiences of women with bulimia nervosa. Eat. Disord. 2003, 11, 73–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stewart, S.H.; Brown, C.G.; Devoulyte, K.; Theakston, J.; Larsen, S.E. Why Do Women with Alcohol Problems Binge Eat?: Exploring Connections between Binge Eating and Heavy Drinking in Women Receiving Treatment for Alcohol Problems. J. Health Psychol. 2006, 11, 409–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolnes, L.J. ‘Feelings stronger than reason’: Conflicting experiences of exercise in women with anorexia nervosa. J. Eat. Disord. 2016, 4, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latzer, Y.; Edelstein-Elkayam, R.; Rabin, O.; Alon, S.; Givon, M.; Tzischinsky, O. The Dark and Comforting Side of Night Eating: Women’s Experiences of Trauma. Psychiatry Int. 2024, 5, 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musolino, C.; Warin, M.; Gilchrist, P. Positioning relapse and recovery through a cultural lens of desire: A South Australian case study of disordered eating. Transcult. Psychiatry 2018, 55, 534–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeppson, J.E.; Richards, P.S.; Hardman, R.K.; Granley, H.M. Binge and purge processes in bulimia nervosa: A qualitative investigation. Eat. Disord. 2003, 11, 115–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, A.; LeCouteur, A.; Hepworth, J. Accounts of experiences of bulimia: A discourse analytic study. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 1998, 24, 193–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannon, J.; Eunson, L.; Munro, C. The patient experience of illness, treatment, and change, during intensive community treatment for severe anorexia nervosa. Eat. Disord. 2017, 25, 279–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serpell, L.; Treasure, J.; Teasdale, J.; Sullivan, V. Anorexia nervosa: Friend or foe? Int. J. Eat. Disord. 1999, 25, 177–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warin, M.J. Reconfiguring relatedness in anorexia. Anthropol. Med. 2006, 13, 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomsen, S.R.; McCoy, J.K.; Williams, M. Internalizing the impossible: Anorexic outpatients’ experiences with women’s beauty and fashion magazines. Eat. Disord. 2001, 9, 49–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Major, L.; Viljoen, D.; Nel, P. The experience of feeling fat for women with anorexia nervosa: An interpretative phenomenological analysis. Eur. J. Psychother. Couns. 2019, 21, 52–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patching, J.; Lawler, J. Understanding women’s experiences of developing an eating disorder and recovering: A life-history approach. Nurs. Inq. 2009, 16, 10–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodgers, R.F.; Fischer, L.E.; Laveway, K.; Laws, K.; Bui, E. Fear of fatness and desire for thinness as distinct experiences: A qualitative exploration. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2022, 55, 530–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Channa, S.; Lavis, A.; Connor, C.; Palmer, C.; Leung, N.; Birchwood, M. Overlaps and Disjunctures: A Cultural Case Study of a British Indian Young Woman’s Experiences of Bulimia Nervosa. Cult. Med. Psychiatry 2019, 43, 361–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Redenbach, J.; Lawler, J. Recovery from disordered eating: What life histories reveal. Contemp. Nurse 2003, 15, 148–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tierney, S.; Fox, J. Living with the anorexic voice: A thematic analysis. Psychol. Psychother. 2010, 83, 243–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moola, F.J.; Gairdner, S.; Amara, C. Speaking on behalf of the body and activity: Investigating the activity experiences of Canadian women living with anorexia nervosa. Ment. Health Phys. Act. 2015, 8, 44–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brownstone, L.M.; Kelly, D.A.; Maloul, E.K.; Dinneen, J.L.; Palazzolo, L.A.; Raque, T.L.; Greene, A.K. “It’s just not comfortable to exist in a body”: Transgender/gender nonbinary individuals’ experiences of body and eating distress during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychol. Sex. Orientat. Gend. Divers. 2022, 9, 434–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, M.; Manuel, J.; Lacey, C.; Pitama, S.; Cunningham, R.; Jordan, J. ‘E koekoe te Tūī, e ketekete te Kākā, e kuku te Kererū, The Tūī chatters, the Kākā cackles, and the Kererū coos’: Insights into explanatory factors, treatment experiences and recovery for Māori with eating disorders—A qualitative study. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 2024, 58, 365–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrop, E.N.; Hecht, H.K.; Harner, V.; Call, J.; Holloway, B.T. “How Do I Exist in This Body That’s Outside of the Norm?” Trans and Nonbinary Experiences of Conformity, Coping, and Connection in Atypical Anorexia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mirabella, M.; Giovanardi, G.; Fortunato, A.; Senofonte, G.; Lombardo, F.; Lingiardi, V.; Speranza, A.M. The Body I Live in. Perceptions and Meanings of Body Dissatisfaction in Young Transgender Adults: A Qualitative Study. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 3733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turner, B.J.; Yiu, A.; Layden, B.K.; Claes, L.; Zaitsoff, S.; Chapman, A.L. Temporal associations between disordered eating and nonsuicidal self-injury: Examining symptom overlap over 1 year. Behav. Ther. 2015, 46, 125–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, F.; Bewick, B.M.; Barkham, M.; House, A.O.; Hill, A.J. Co-occurrence of self-reported disordered eating and self-harm in UK university students. Br. J. Clin. Psychol. 2009, 48, 397–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, K.A.; Haynos, A.F. A theoretical review of interpersonal emotion regulation in eating disorders: Enhancing knowledge by bridging interpersonal and affective dysfunction. J. Eat. Disord. 2020, 8, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilboa-Schechtman, E.; Avnon, L.; Zubery, E.; Jeczmien, P. Emotional processing in eating disorders: Specific impairment or general distress related deficiency? Depress. Anxiety 2006, 23, 331–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cludius, B.; Mennin, D.; Ehring, T. Emotion regulation as a transdiagnostic process. Emotion 2020, 20, 37–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldao, A. Introduction to the Special Issue: Emotion Regulation as a Transdiagnostic Process. Cogn. Ther. Res. 2016, 40, 257–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bordo, S. Unbearable Weight: Feminism, Western Culture, and the Body; University of California Press: Oakland, CA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Malson, H. The Thin Woman: Feminism, Post-Structuralism and the Social Psychology of Anorexia Nervosa, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Hooley, J.M.; Franklin, J.C. Why Do People Hurt Themselves? A New Conceptual Model of Nonsuicidal Self-Injury. Clin. Psychol. Sci. 2017, 6, 428–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzsimmons-Craft, E.E.; Bardone-Cone, A.M.; Harney, M.B. Development and validation of the Body, Eating, and Exercise Comparison Orientation Measure (BEECOM) among college women. Body Image 2012, 9, 476–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzsimmons-Craft, E.E.; Harney, M.B.; Koehler, L.G.; Danzi, L.E.; Riddell, M.K.; Bardone-Cone, A.M. Explaining the relation between thin ideal internalization and body dissatisfaction among college women: The roles of social comparison and body surveillance. Body Image 2012, 9, 43–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pompili, M.; Mancinelli, I.; Girardi, P.; Ruberto, A.; Tatarelli, R. Suicide in anorexia nervosa: A meta-analysis. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2004, 36, 99–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.R.; Zuromski, K.L.; Dodd, D.R. Eating disorders and suicidality: What we know, what we don’t know, and suggestions for future research. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2018, 22, 63–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ålgars, M.; Alanko, K.; Santtila, P.; Sandnabba, N.K. Disordered eating and gender identity disorder: A qualitative study. Eat. Disord. 2012, 20, 300–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cusack, C.E.; Iampieri, A.O.; Galupo, M.P. “I’m still not sure if the eating disorder is a result of gender dysphoria”: Trans and nonbinary individuals’ descriptions of their eating and body concerns in relation to their gender. Psychol. Sex. Orientat. Gend. Divers. 2022, 9, 422–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bem, S. Gender schema theory: A cognitive account of sex typing. Psychol. Rev. 1981, 88, 354–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cusack, C.E.; Levenson, N.H.; Galupo, M.P. “Anorexia Wants to Kill Me, Dysphoria Wants Me to Live”: Centering Transgender and Nonbinary Experiences in Eating Disorder Treatment. J. LGBTQ Issues Couns. 2022, 16, 265–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romito, M.; Salk, R.H.; Roberts, S.R.; Thoma, B.C.; Levine, M.D.; Choukas-Bradley, S. Exploring transgender adolescents’ body image concerns and disordered eating: Semi-structured interviews with nine gender minority youth. Body Image 2021, 37, 50–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, C.E.; Hazzard, V.M.; Loth, K.A.; Larson, N.; Hooper, L.; Neumark-Sztainer, D. The interplay between food insecurity and family factors in relation to disordered eating in adolescence. Appetite 2023, 189, 106994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abene, J.A.; Tong, J.; Minuk, J.; Lindenfeldar, G.; Chen, Y.; Chao, A.M. Food insecurity and binge eating: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2023, 56, 1301–1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazzard, V.M.; Hooper, L.; Larson, N.; Loth, K.A.; Wall, M.M.; Neumark-Sztainer, D. Associations between severe food insecurity and disordered eating behaviors from adolescence to young adulthood: Findings from a 10-year longitudinal study. Prev. Med. 2022, 154, 106895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shomaker, L.B.; Tanofsky-Kraff, M.; Elliott, C.; Wolkoff, L.E.; Columbo, K.M.; Ranzenhofer, L.M.; Roza, C.A.; Yanovski, S.Z.; Yanovski, J.A. Salience of loss of control for pediatric binge episodes: Does size really matter? Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2010, 43, 707–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vannucci, A.; Theim, K.R.; Kass, A.E.; Trockel, M.; Genkin, B.; Rizk, M.; Weisman, H.; Bailey, J.O.; Sinton, M.M.; Aspen, V.; et al. What constitutes clinically significant binge eating? Associatvan hoion between binge features and clinical validators in college-age women. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2013, 46, 226–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Hoeken, D.; Hoek, H.W. Review of the burden of eating disorders: Mortality, disability, costs, quality of life, and family burden. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 2020, 33, 521–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, M.J. Cognitive theory in anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa: Progress, development and future directions. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2005, 25, 511–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waller, G.; Beard, J. Recent Advances in Cognitive-Behavioural Therapy for Eating Disorders (CBT-ED). Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2024, 26, 351–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Responding to Distress | Self-Harm as a Positive Experience | Defining the Self |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Responding to Distress | Self-Harm as a Rewarding Experience | Defining the Self |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ambler, F.; Hill, A.J.; Willis, T.A.; Gregory, B.; Mujahid, S.; Romeu, D.; Brennan, C. How Do the Psychological Functions of Eating Disorder Behaviours Compare with Self-Harm? A Systematic Qualitative Evidence Synthesis. Healthcare 2025, 13, 1914. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13151914

Ambler F, Hill AJ, Willis TA, Gregory B, Mujahid S, Romeu D, Brennan C. How Do the Psychological Functions of Eating Disorder Behaviours Compare with Self-Harm? A Systematic Qualitative Evidence Synthesis. Healthcare. 2025; 13(15):1914. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13151914

Chicago/Turabian StyleAmbler, Faye, Andrew J. Hill, Thomas A. Willis, Benjamin Gregory, Samia Mujahid, Daniel Romeu, and Cathy Brennan. 2025. "How Do the Psychological Functions of Eating Disorder Behaviours Compare with Self-Harm? A Systematic Qualitative Evidence Synthesis" Healthcare 13, no. 15: 1914. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13151914

APA StyleAmbler, F., Hill, A. J., Willis, T. A., Gregory, B., Mujahid, S., Romeu, D., & Brennan, C. (2025). How Do the Psychological Functions of Eating Disorder Behaviours Compare with Self-Harm? A Systematic Qualitative Evidence Synthesis. Healthcare, 13(15), 1914. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13151914