Tell Me What You’ve Done, and I’ll Predict What You’ll Do: The Role of Motivation and Past Behavior in Exercise Adherence

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Method

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Participants

2.3. Procedures

- (1)

- Pre-selection (weeks 1 and 2): prior to data collection, all participants with less than six months of practice and/or who had more than one episode of withdrawal (at least a month) were excluded.

- (2)

- Gym attendance verification (weeks 4 and 5): Participants were selected, which matches the number of subjects who had a weekly frequency (i.e., at least one time a week) in the six months prior to data collection and in the following six months. Regarding gym attendance criteria. Given the specificity of exercise practice, it is very common for people to have several withdrawal episodes, especially in summer holidays. Therefore, only one episode of withdrawal (i.e., with no weekly attendance) was allowed. These criteria guarantee people exercise continuously for an extended period.

- (3)

- Final verification (weeks 26 and 27): Six months after data collection, the same criteria were applied to identify the participants who kept the minimum weekly attendance in the last six months and had a single episode of withdrawal. Due to the nature of common conflicts in exercise practice, especially during periods such as summer vacation, it is acceptable to consider short episodes of withdrawal as part of an ongoing pattern of practice [45]. Studies indicate that temporary interruptions do not necessarily compromise exercise adherence, as long as the minimum frequency (e.g., once a week) is maintained most of the time [46].

2.4. Instruments

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Preliminary Analysis

3.2. Measurement Model (CFA)

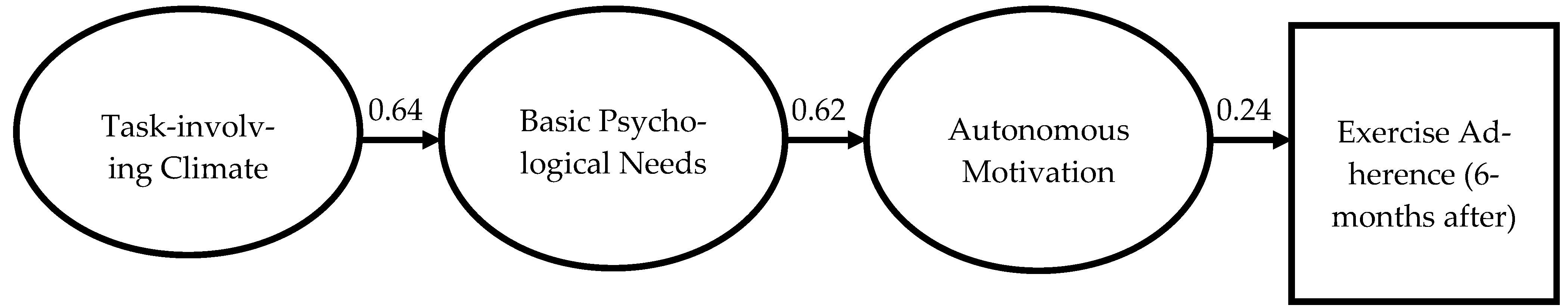

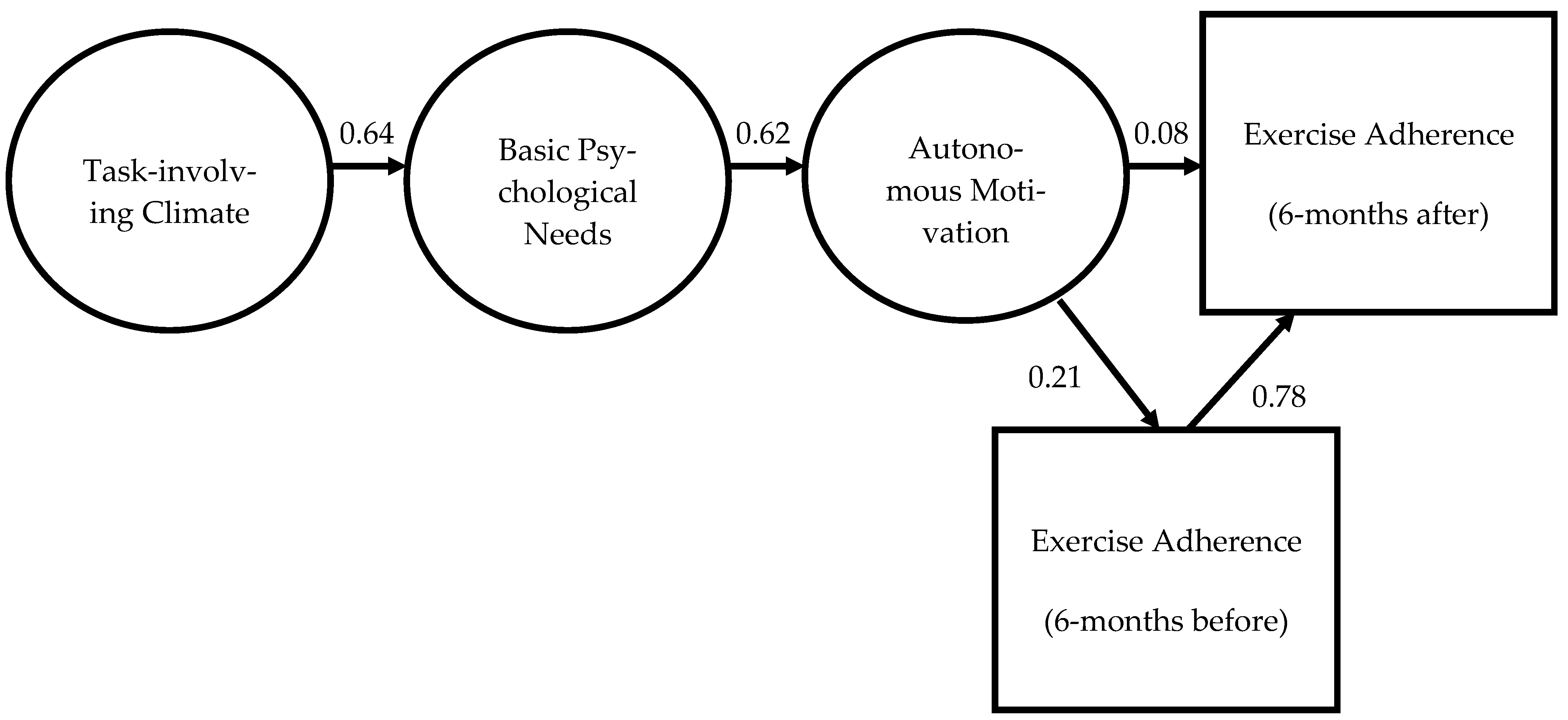

3.3. Structural Equation Model (SEM)

4. Discussion

5. Limitations and Agenda for the Future

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Festino, E.; Papale, O.; Di Rocco, F.; De Maio, M.; Cortis, C.; Fusco, A. Effect of Physical Activity Behaviors, Team Sports, and Sitting Time on Body Image and Exercise Dependence. Sports 2024, 12, 260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caponnetto, P.; Casu, M.; Amato, M.; Cocuzza, D.; Galofaro, V.; La Morella, A.; Paladino, S.; Pulino, K.; Raia, N.; Recupero, F.; et al. The Effects of Physical Exercise on Mental Health: From Cognitive Improvements to Risk of Addiction. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 13384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wågan, F.A.; Darvik, M.D.; Pedersen, A.V. Associations between Self-Esteem, Psychological Stress, and the Risk of Exercise Dependence. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, I.-M.; Shiroma, E.J.; Lobelo, F.; Puska, P.; Blair, S.N.; Katzmarzyk, P.T.; Lancet Physical Activity Series Working Group. Effect of Physical Inactivity on Major Non-Communicable Diseases Worldwide: An Analysis of Burden of Disease and Life Expectancy. Lancet 2012, 380, 219–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warburton, D.E.R.; Bredin, S.S.D. Health Benefits of Physical Activity: A Systematic Review of Current Systematic Reviews. Curr. Opin. Cardiol. 2017, 32, 541–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiPietro, L.; Buchner, D.M.; Marquez, D.X.; Pate, R.R.; Pescatello, L.S.; Whitt-Glover, M.C. New Scientific Basis for the 2018 U.S. Physical Activity Guidelines. J. Sport Health Sci. 2019, 8, 197–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekelund, U.; Tarp, J.; Steene-Johannessen, J.; Hansen, B.H.; Jefferis, B.; Fagerland, M.W.; Whincup, P.; Diaz, K.M.; Hooker, S.P.; Chernofsky, A.; et al. Dose-Response Associations between Accelerometry Measured Physical Activity and Sedentary Time and All Cause Mortality: Systematic Review and Harmonised Meta-Analysis. BMJ 2019, 366, l4570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strain, T.; Flaxman, S.; Guthold, R.; Semenova, E.; Cowan, M.; Riley, L.M.; Bull, F.C.; Stevens, G.A.; Country Data Author Group. National, Regional, and Global Trends in Insufficient Physical Activity among Adults from 2000 to 2022: A Pooled Analysis of 507 Population-Based Surveys with 5.7 Million Participants. Lancet Glob. Health 2024, 12, E1232–E1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallal, P.C.; Andersen, L.B.; Bull, F.C.; Guthold, R.; Haskell, W.; Ekelund, U.; Lancet Physical Activity Series Working Group. Global Physical Activity Levels: Surveillance Progress, Pitfalls, and Prospects. Lancet 2012, 380, 247–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guthold, R.; Stevens, G.A.; Riley, L.M.; Bull, F.C. Global Trends in Insufficient Physical Activity among Adolescents: A Pooled Analysis of 298 Population-Based Surveys with 1.6 Million Participants. Lancet Child. Adolesc. Health 2020, 4, 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Special Eurobarometer 525 Sport and Physical Activity. Available online: https://europa.eu/eurobarometer/surveys/detail/2668 (accessed on 16 July 2025).

- European Comission. Special Eurobarometer 334 Sport and Physical Activity. Available online: https://europa.eu/eurobarometer/surveys/detail/776 (accessed on 16 July 2025).

- European Comission. Special Eurobarometer 412 Sport and Physical Activity. Available online: https://europa.eu/eurobarometer/surveys/detail/1116 (accessed on 16 July 2025).

- Special Eurobarometer 472 Sport and Physical Activity. Available online: https://europa.eu/eurobarometer/surveys/detail/2164 (accessed on 16 July 2025).

- Aaltonen, S.; Leskinen, T.; Morris, T.; Alen, M.; Kaprio, J.; Liukkonen, J.; Kujala, U. Motives for and Barriers to Physical Activity in Twin Pairs Discordant for Leisure Time Physical Activity for 30 Years. Int. J. Sports Med. 2012, 33, 157–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caudwell, K.M.; Keatley, D.A. The Effect of Men′s Body Attitudes and Motivation for Gym Attendance. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2016, 30, 2550–2556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholls, J.G. Achievement Motivation: Conceptions of Ability, Subjective Experience, Task Choice, and Performance. Psychol. Rev. 1984, 91, 328–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholls, J.G. The Competitive Ethos and Democratic Education; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Duda, J.L. The Conceptual and Empirical Foundations of Empowering CoachingTM: Setting the Stage for the PAPA Project. Int. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2013, 11, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appleton, P.R.; Ntoumanis, N.; Quested, E.; Viladrich, C.; Duda, J.L. Initial Validation of the Coach-Created Empowering and Disempowering Motivational Climate Questionnaire (EDMCQ-C). Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2016, 22, 53–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagger, M.; Chatzisarantis, N. Self-Determination Theory and the Psychology of Exercise. Int. Rev. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2008, 1, 79–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, G. Motivation in Sport and Exercise from an Achievement Goal Theory Perspective After 30 Years, Where Are We? 3rd ed.; Roberts, G., Treasure, D., Eds.; Human Kinetics: Champaign, IL, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Deci, E.; Ryan, R. Intrinsic Motivation and Self-Determination in Human Behavior; Plenum Press: New York, NY, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, R.; Deci, E. Self-Determination Theory: Basic Psychological Needs in Motivation, Development, and Wellness; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2017; ISBN 978-1-4625-3896-6. [Google Scholar]

- Michie, S.; Atkins, L.; West, R. The Behaviour Change Wheel: A Guide to Designing Interventions; Silverback: Sutton, UK, 2014; ISBN 978-1-912141-08-1. [Google Scholar]

- Georgiadis, M.; Biddle, S.; Chatzisarantis, N. The Mediating Role of Self-Determination in the Relationship between Goal Orientations and Physical Self-Worth in Greek Exercisers. Eur. J. Sport Sci. 2001, 1, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Biddle, S. Understanding Young People’s Motivation Toward Exercise: An Integration of Sport Ability Beliefs, Achievement Goal Theory, and Self-Determination Theory. In Intrinsic Motivations and Self-Determination in Exercise and Sport; Hagger, M., Chatzisarantis, N., Eds.; Human Kinetics: Champaign, IL, USA, 2007; pp. 193–208. [Google Scholar]

- Klain, I.P.; Cid, L.; Matos, D.G.D.; Leitão, J.C.; Hickner, R.C.; Moutão, J. Motivational Climate, Goal Orientation and Exercise Adherence in Fitness Centers and Personal Training Contexts. Mot. Rev. Educ. Fis. 2014, 20, 249–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, F.; Bento, T.; Cid, L.; Pereira Neiva, H.; Teixeira, D.; Moutão, J.; Almeida Marinho, D.; Monteiro, D. Can Interpersonal Behavior Influence the Persistence and Adherence to Physical Exercise Practice in Adults? A Systematic Review. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 2141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez, M.S.; Balaguer, I.; Castillo, I.; Duda, J.L. The Coach-Created Motivational Climate, Young Athletes’ Well-Being, and Intentions to Continue Participation. J. Clin. Sport Psychol. 2012, 6, 166–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markland, D.; Tobin, V.J. Need Support and Behavioural Regulations for Exercise among Exercise Referral Scheme Clients: The Mediating Role of Psychological Need Satisfaction. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2010, 11, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, D.; Teixeira, D.S.; Travassos, B.; Duarte-Mendes, P.; Moutão, J.; Machado, S.; Cid, L. Perceived Effort in Football Athletes: The Role of Achievement Goal Theory and Self-Determination Theory. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, P.J.; Carraça, E.V.; Markland, D.; Silva, M.N.; Ryan, R.M. Exercise, Physical Activity, and Self-Determination Theory: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2012, 9, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viveiros, B.; Jacinto, M.; Antunes, R.; Matos, R.; Amaro, N.; Cid, L.; Couto, N.; Monteiro, D. Application of the Hierarchical Model of Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivation in the Context of Exercise: A Systematic Review. Front. Psychol. 2025, 16, 1512270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vallerand, R.J. A Hierarchical Model of Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivation for Sport and Physical Activity. In Intrinsic Motivation and Self-Determination in Exercise and Sport; Human Kinetics: Champaign, IL, USA, 2007; pp. 255–279, 356–363. ISBN 978-0-7360-6250-3. [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues, F.; Teixeira, D.S.; Neiva, H.P.; Cid, L.; Monteiro, D. The Bright and Dark Sides of Motivation as Predictors of Enjoyment, Intention, and Exercise Persistence. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2020, 30, 787–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hagger, M.S. Habit and Physical Activity: Theoretical Advances, Practical Implications, and Agenda for Future Research. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2019, 42, 118–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagger, M.S.; Chatzisarantis, N.L.D.; Biddle, S.J.H. A Meta-Analytic Review of the Theories of Reasoned Action and Planned Behavior in Physical Activity: Predictive Validity and the Contribution of Additional Variables. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2002, 24, 3–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, A.R.; Gonçalves, A.M.; Maddux, J.E.; Carneiro, L. The Intention-Behaviour Gap: An Empirical Examination of an Integrative Perspective to Explain Exercise Behaviour. Int. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2018, 16, 607–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlachopoulos, S.P.; Neikou, E. A Prospective Study of the Relationships of Autonomy, Competence, and Relatedness with Exercise Attendance, Adherence, and Dropout. J. Sports Med. Phys. Fit. 2007, 47, 475–482. [Google Scholar]

- Marcus, B.H.; Simkin, L.R. The Transtheoretical Model: Applications to Exercise Behavior. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 1994, 26, 1400–1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, B.G.; Pargman, D.; Weinberg, R.S. Foundations of Exercise Psychology; Fitness Information Technology: Morgantown, MV, USA, 2002; ISBN 978-1-885693-34-1. [Google Scholar]

- Buckworth, J.; Dishman, R.K. Exercise Adherence. In Handbook of Sport Psychology, 3rd ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2007; pp. 509–536. ISBN 978-0-471-73811-4. [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues, F.; Teixeira, D.S.; Cid, L.; Monteiro, D. Have You Been Exercising Lately? Testing the Role of Past Behavior on Exercise Adherence. J. Health Psychol. 2021, 26, 1482–1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dishman, R.K.; Heath, G.W.; Lee, I.-M. Physical Activity Epidemiology; Human Kinetics: Champaign, IL, USA, 2012; ISBN 978-1-4925-8130-7. [Google Scholar]

- Marcus, B.; Forsyth, L. Motivating People to Be Physically Active; Physical Activity Intervention Series; Human Kineticks: Champaign, IL, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, J.A.; Barron, K.E. A Test of Multiple Achievement Goal Benefits in Physical Education Activities. J. Appl. Sport Psychol. 2006, 18, 114–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cid, L.; Moutão, J.; Leitão, J.; Alves, J. Tradução e Validação Da Adaptação Para o Exercício Do Perceived Motivational Climate Sport Questionnaire—Translation and Validation of the Exercise Adaptation of the Perceived Motivational Climate Sport Questionnaire. Mot. Rev. Educ. Fis. 2012, 18, 708–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlachopoulos, S.P.; Michailidou, S. Development and Initial Validation of a Measure of Autonomy, Competence, and Relatedness in Exercise: The Basic Psychological Needs in Exercise Scale. Meas. Phys. Educ. Exerc. Sci. 2006, 10, 179–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moutão, J.; Cid, L.; Alves, J.; Leitão, J.C.; Vlachopoulos, S.P. Validation of the Basic Psychological Needs in Exercise Scale in a Portuguese Sample. Span. J. Psychol. 2012, 15, 399–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cid, L.; Rodrigues, F.; Teixeira, D.S.; Alves, J.; Machado, S.; Murillo-Rodríguez, E.; Monteiro, D. Exploração de um modelo de segunda ordem da Versão Portuguesa da Basic Psychological Needs in Exercise Scale (BPNESp): Validade do constructo e invariância. Cuad. Psicol. Deporte 2020, 20, 95–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cid, L.; Monteiro, D.; Teixeira, D.; Teques, P.; Alves, S.; Moutão, J.; Silva, M.; Palmeira, A. The Behavioral Regulation in Exercise Questionnaire (BREQ-3) Portuguese-Version: Evidence of Reliability, Validity and Invariance Across Gender. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 1940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markland, D.; Tobin, V. A Modification to the Behavioural Regulation in Exercise Questionnaire to Include an Assessment of Amotivation. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2004, 26, 191–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cid, L.; Moutão, J.; Leitão, J.; Alves, J. Behavioral Regulation Assessment in Exercise: Exploring an Autonomous and Controlled Motivation Index. Span. J. Psychol. 2012, 15, 1520–1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, P.M.; Rogers, W.T.; Rodgers, W.M.; Wild, T.C. The Psychological Need Satisfaction in Exercise Scale. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2006, 28, 231–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klain, I.P.; de Matos, D.G.; Leitão, J.C.; Cid, L.; Moutão, J. Self-Determination and Physical Exercise Adherence in the Contexts of Fitness Academies and Personal Training. J. Hum. Kinet. 2015, 46, 241–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling, 4th ed.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis, 8th ed.; Cengage: Hampshire, UK, 2019; ISBN 978-1-4737-5654-0. [Google Scholar]

- Cid, L.; Monteiro, D.; Teixeira, D.S.; Evmenenko, A.; Andrade, A.; Bento, T.; Vitorino, A.; Couto, N.; Rodrigues, F. Assessment in Sport and Exercise Psychology: Considerations and Recommendations for Translation and Validation of Questionnaires. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 806176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, H.W.; Hau, K.-T.; Wen, Z. In Search of Golden Rules: Comment on Hypothesis-Testing Approaches to Setting Cutoff Values for Fit Indexes and Dangers in Overgeneralizing Hu and Bentler′s (1999) Findings. Struct. Equ. Model. Multidiscip. J. 2004, 11, 320–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Partial, Conditional, and Moderated Moderated Mediation: Quantification, Inference, and Interpretation. Commun. Monogr. 2018, 85, 4–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nevitt, J.; Hancock, G.R. Performance of Bootstrapping Approaches to Model Test Statistics and Parameter Standard Error Estimation in Structural Equation Modeling. Struct. Equ. Model. Multidiscip. J. 2001, 8, 353–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soper, D.S. Critical F-Value Calculator, Software. 2025. Available online: https://www.danielsoper.com/statcalc (accessed on 16 July 2025).

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. The “What” and “Why” of Goal Pursuits: Human Needs and the Self-Determination of Behavior. Psychol. Inq. 2000, 11, 227–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. Self-Determination Theory: A Macrotheory of Human Motivation, Development, and Health. Can. Psychol./Psychol. Can. 2008, 49, 182–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. Facilitating Optimal Motivation and Psychological Well-Being across Life’s Domains. Can. Psychol./Psychol. Can. 2008, 49, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Self-Determination Theory and the Facilitation of Intrinsic Motivation, Social Development, and Well-Being. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Introduction: Active Human Nature: Self-Determination Theory and the Promotion and Maintenance of Sport, Exercise, and Health. In Intrinsic Motivation and Self-Determination in Exercise and Sport; Human Kineticks: Champaing, IL, USA, 2007; pp. 1–19. ISBN 978-0-7360-6250-3. [Google Scholar]

- Chatzisarantis, N.; Hagger, M. Intrinsic Motivation and Self-Determination in Exercise and Sport: Reflecting on the Past and Sketching the Future. In Intrinsic Motivation and Self-Determination in Exercise and Sport; Human Kinetics: Champaign, IL, USA, 2007; pp. 281–296. ISBN 978-0-7360-6250-3. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, R.; Wang, L.; Wang, B.; Zhou, Y. Motivational Climate, Need Satisfaction, Self-Determined Motivation, and Physical Activity of Students in Secondary School Physical Education in China. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ntoumanis, N. A Self-Determination Approach to the Understanding of Motivation in Physical Education. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 2001, 71, 225–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Standage, M.; Duda, J.L.; Ntoumanis, N. A Model of Contextual Motivation in Physical Education: Using Constructs from Self-Determination and Achievement Goal Theories to Predict Physical Activity Intentions. J. Educ. Psychol. 2003, 95, 97–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarrazin, P.; Vallerand, R.; Guillet, E.; Pelletier, L.; Cury, F. Motivation and Dropout in Female Handballers: A 21-Month Prospective Study. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 2002, 32, 395–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinboth, M.; Duda, J.L. Perceived Motivational Climate, Need Satisfaction and Indices of Well-Being in Team Sports: A Longitudinal Perspective. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2006, 7, 269–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonough, M.H.; Crocker, P.R.E. Testing Self-Determined Motivation as a Mediator of the Relationship between Psychological Needs and Affective and Behavioral Outcomes. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2007, 29, 645–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vierling, K.K.; Standage, M.; Treasure, D.C. Predicting Attitudes and Physical Activity in an “at-Risk” Minority Youth Sample: A Test of Self-Determination Theory. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2007, 8, 795–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lally, P.; Gardner, B. Promoting Habit Formation. Health Psychol. Rev. 2013, 7, S137–S158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Miao, C. The Mediating Role of Competence, Autonomy, and Relatedness in the Activation and Maintenance of Sports Participation Behavior. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 27124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radel, R.; Pelletier, L.; Pjevac, D.; Cheval, B. The Links between Self-Determined Motivations and Behavioral Automaticity in a Variety of Real-Life Behaviors. Motiv. Emot. 2017, 41, 443–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. Perceived Behavioral Control, Self-Efficacy, Locus of Control, and the Theory of Planned Behavior1. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2002, 32, 665–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagger, M.S.; Polet, J.; Lintunen, T. The Reasoned Action Approach Applied to Health Behavior: Role of Past Behavior and Tests of Some Key Moderators Using Meta-Analytic Structural Equation Modeling. Soc. Sci. Med. 2018, 213, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hagger, M.S.; Chan, D.K.C.; Protogerou, C.; Chatzisarantis, N.L.D. Using Meta-Analytic Path Analysis to Test Theoretical Predictions in Health Behavior: An Illustration Based on Meta-Analyses of the Theory of Planned Behavior. Prev. Med. 2016, 89, 154–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, H.; Wang, A.; Pei, R.; Piao, M. Effects of Habit Formation Interventions on Physical Activity Habit Strength: Meta-Analysis and Meta-Regression. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2023, 20, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaushal, N.; Rhodes, R.E. Exercise Habit Formation in New Gym Members: A Longitudinal Study. J. Behav. Med. 2015, 38, 652–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armitage, C.J. Can the Theory of Planned Behavior Predict the Maintenance of Physical Activity? Health Psychol. 2005, 24, 235–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| M ± SD | MC | BPN | AM | PA | FA | CR | AVE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Task-Involving Climate | 4.00 ± 0.50 | - | 0.65 | 0.72 | ||||

| Basic Psychological Needs | 4.02 ± 0.38 | 0.40 ** | - | 0.80 | 0.63 | |||

| Autonomous Motivation | 3.43 ± 0.49 | 0.27 ** | 0.37 ** | - | 0.63 | 0.55 | ||

| Past Adherence | 61.1 ± 28.7 | −0.01 | 0.13 * | 0.14 * | - | - | 0.96 | |

| Future Adherence | 54.1 ± 25.2 | 0.03 | 0.21 ** | 0.13 * | 0.80 ** | - | - | 0.94 |

| Parameter | Total Effects | Direct Effects | Indirect Effects |

|---|---|---|---|

| Task-Involving Climate → BPN | 0.64 * | 0.64 * | - |

| Task-Involving Climate → Autonomous Motivation | 0.39 * | - | 0.39 * |

| Task-Involving Climate → Past Adherence | 0.08 | - | 0.08 |

| Task-Involving Climate → Future Adherence | 0.09 | - | 0.09 |

| BPN → Autonomous Motivation | 0.62 * | 0.62 * | - |

| BPN → Past Adherence | 0.13 * | - | 0.13 * |

| BPN → Future Adherence | 0.15 * | - | 0.15 * |

| Autonomous Motivation → Past Adherence | 0.21 * | 0.21 * | - |

| Autonomous Motivation → Future Adherence | 0.24 * | 0.08 | 0.16 * |

| Past Adherence → Future Adherence | 0.78 * | 0.78 * | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cid, L.; Monteiro, D.; Bento, T.; Jacinto, M.; Vitorino, A.; Teixeira, D.S.; Duarte-Mendes, P.; Bastos, V.; Couto, N. Tell Me What You’ve Done, and I’ll Predict What You’ll Do: The Role of Motivation and Past Behavior in Exercise Adherence. Healthcare 2025, 13, 1879. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13151879

Cid L, Monteiro D, Bento T, Jacinto M, Vitorino A, Teixeira DS, Duarte-Mendes P, Bastos V, Couto N. Tell Me What You’ve Done, and I’ll Predict What You’ll Do: The Role of Motivation and Past Behavior in Exercise Adherence. Healthcare. 2025; 13(15):1879. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13151879

Chicago/Turabian StyleCid, Luís, Diogo Monteiro, Teresa Bento, Miguel Jacinto, Anabela Vitorino, Diogo S. Teixeira, Pedro Duarte-Mendes, Vasco Bastos, and Nuno Couto. 2025. "Tell Me What You’ve Done, and I’ll Predict What You’ll Do: The Role of Motivation and Past Behavior in Exercise Adherence" Healthcare 13, no. 15: 1879. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13151879

APA StyleCid, L., Monteiro, D., Bento, T., Jacinto, M., Vitorino, A., Teixeira, D. S., Duarte-Mendes, P., Bastos, V., & Couto, N. (2025). Tell Me What You’ve Done, and I’ll Predict What You’ll Do: The Role of Motivation and Past Behavior in Exercise Adherence. Healthcare, 13(15), 1879. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13151879