Mental Health Impacts of the COVID-19 Pandemic on College Students: A Literature Review with Emphasis on Vulnerable and Minority Populations

Abstract

1. Introduction

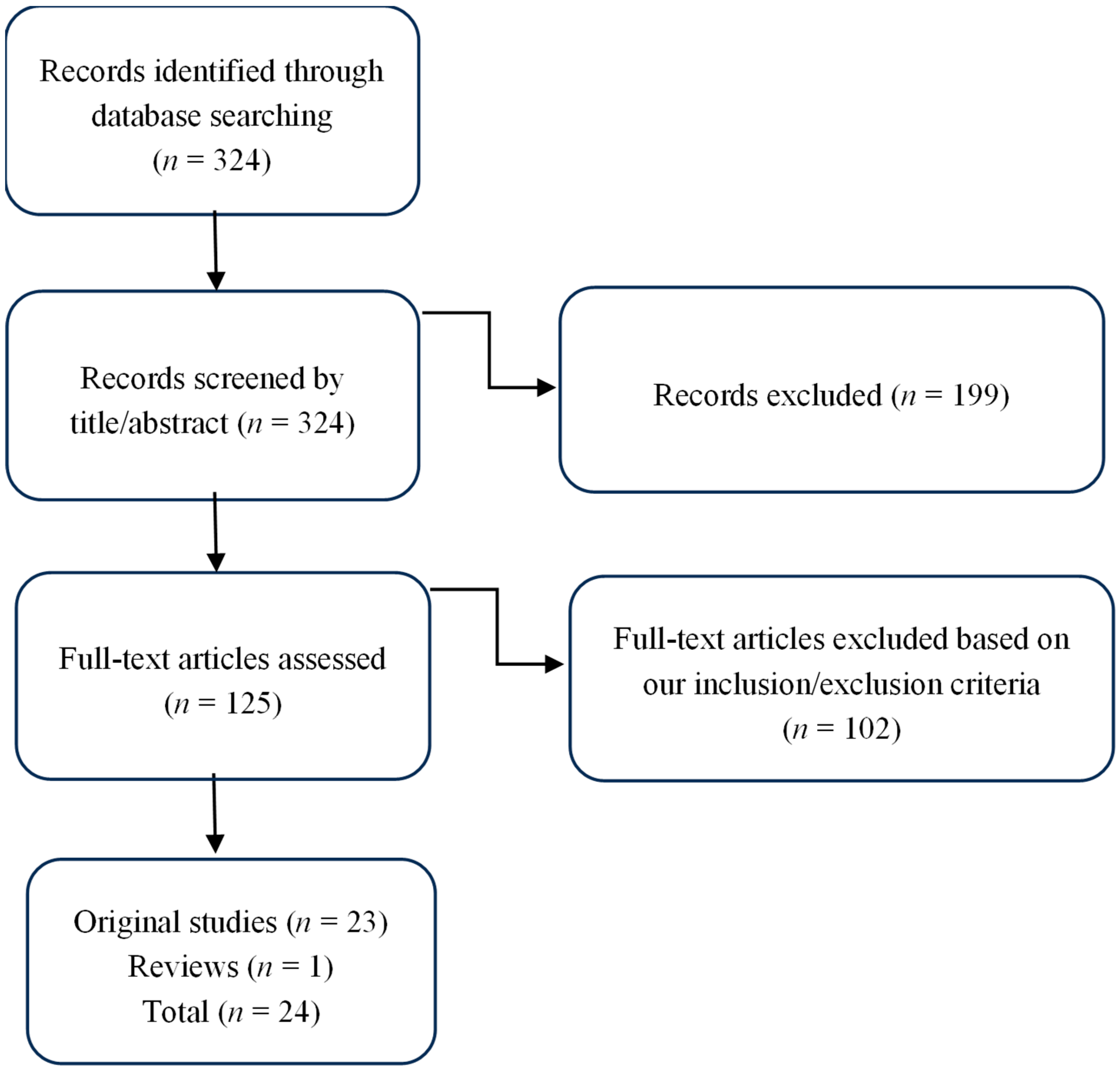

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Literature Search

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

3. Results

3.1. Mental Health of College Students Belonging to National, Ethnic, and Racial Minorities

3.2. Mental Health of College Students Belonging to Migrant Minorities

3.3. Mental Health of College Students Belonging to Gender- and Sexuality-Based Minorities

3.4. Mental Health of College Students from Low-Income Backgrounds

3.5. Diverging Patterns and Exceptions

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Esterwood, E.; Saeed, S.A. Past Epidemics, Natural Disasters, COVID-19, and Mental Health: Learning from History as We Deal with the Present and Prepare for the Future. Psychiatr. Q. 2020, 91, 1121–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panchal, N.; Kamal, R.; Orgera, K.; Cox, C.; Garfield, R.; Hamel, L.; Chidambaram, P. The Implications of COVID-19 for Mental Health and Substance Use; Kaiser Family Foundation: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2020; Available online: https://www.kff.org/coronavirus-covid-19/issue-brief/the-implications-of-covid-19-for-mental-health-and-substance-use/ (accessed on 7 January 2025).

- Armour, C.; McGlinchey, E.; Butter, S.; McAloney-Kocaman, K.; McPherson, K.E. The COVID-19 Psychological Wellbeing Study: Understanding the Longitudinal Psychosocial Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic in the UK; a Methodological Overview Paper. J. Psychopathol. Behav. Assess. 2021, 43, 174–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McBride, O.; Murphy, J.; Shevlin, M.; Gibson Miller, J.; Hartman, T.K.; Hyland, P.; Levita, L.; Mason, L.; Martinez, A.P.; McKay, R.; et al. Monitoring the Psychological Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic in the General Population: An Overview of the Context, Design and Conduct of the COVID-19 Psychological Research Consortium (C19PRC) Study. PsyArXiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neil, G.; Grant, R. New Poll: COVID-19 Impacting Mental Well-Being: Americans Feeling Anxious, Especially for Loved Ones; Older Adults Are Less Anxious; APA: Washington, DC, USA, 2020; Available online: https://www.psychiatry.org/news-room/news-releases/new-poll-covid-19-impacting-mental-well-being-amer (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- Loades, M.E.; Chatburn, E.; Higson-Sweeney, N.; Reynolds, S.; Shafran, R.; Brigden, A.; Linney, C.; McManus, M.N.; Borwick, C.; Crawley, E. Rapid Systematic Review: The Impact of Social Isolation and Loneliness on the Mental Health of Children and Adolescents in the Context of COVID-19. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2020, 59, 1218–1239.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molock, S.D.; Parchem, B. The Impact of COVID-19 on College Students from Communities of Color. J. Am. Coll. Health 2021, 70, 2399–2405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, C.; Hegde, S.; Smith, A.; Wang, X.; Sasangohar, F. Effects of COVID-19 on College Students’ Mental Health in the United States: Interview Survey Study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e21279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Hegde, S.; Son, C.; Keller, B.; Smith, A.; Sasangohar, F. Investigating Mental Health of US College Students During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Cross-Sectional Survey Study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e22817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, J.; Lipsitz, O.; Nasri, F.; Lui, L.M.W.; Gill, H.; Phan, L.; Chen-Li, D.; Iacobucci, M.; Ho, R.; Majeed, A.; et al. Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Mental Health in the General Population: A Systematic Review. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 277, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agyapong-Opoku, G.; Agyapong, B.; Obuobi-Donkor, G.; Eboreime, E. Depression and Anxiety among Undergraduate Health Science Students: A Scoping Review of the Literature. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, H. Literature Review of Mental Health Among College Students During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Stud. Psychol. Sci. 2024, 2, 48–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, A.; Wu, Y.; Han, N.; Huang, H. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Mental Health of College Students: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 669119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zarowski, B.; Giokaris, D.; Green, O. Effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic on University Students’ Mental Health: A Literature Review. Cureus 2024, 16, e54032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Houghton, S.; Glasgow, K. International Students’ Mental Health Amidst COVID-19—A Systematic Review Based on Current Evidence. Educ. Res. Perspect. 2022, 49, 29–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elharake, J.A.; Akbar, F.M.; Malik, A.A.; Gilliam, W.S.; Omer, S.B. Mental Health Impact of COVID-19 among Children and College Students: A Systematic Review. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 2022, 54, 913–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allen, R.E.; Hochard, K.D.; Kannangara, C.; Carson, J. The Road to Recovery: A Two-Year Longitudinal Analysis of Mental Health Among University Students During and After the COVID-19 Pandemic. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riboldi, I.; Capogrosso, C.A.; Piacenti, S.; Calabrese, A.; Lucini Paioni, S.; Bartoli, F.; Crocamo, C.; Carrà, G.; Armes, J.W.; Taylor, C. Mental Health and COVID-19 in University Students: Findings from a Qualitative, Comparative Study in Italy and the UK. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 4071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antwi, C.O.; Belle, M.A.; Ntim, S.Y.; Wu, Y.; Affum-Osei, E.; Aboagye, M.O.; Ren, J. COVID-19 Pandemic and International Students’ Mental Health in China: Age, Gender, Chronic Health Condition and Having Infected Relative as Risk Factors. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 7916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, A.M. An increasing risk of family violence during the COVID-19 pandemic: Strengthening community collaborations to save lives. Forensic Sci. Int. Rep. 2020, 2, 100089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lederer, A.M.; Hoban, M.T.; Lipson, S.K.; Zhou, S.; Eisenberg, D. More Than Inconvenienced: The Unique Needs of U.S. College Students During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Health Educ. Behav. 2020, 48, 14–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudenstine, S.; McNeal, K.; Schulder, T.; Ettman, C.K.; Hernandez, M.; Gvozdieva, K.; Galea, S. Depression and Anxiety During the COVID-19 Pandemic in an Urban, Low-Income Public University Sample. J. Trauma. Stress 2021, 34, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Jeong, H.J.; Kim, S. Stress, Anxiety, and Depression Among Undergraduate Students during the COVID-19 Pandemic and their Use of Mental Health Services. Innov. High Educ. 2021, 46, 519–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.; Rackoff, G.N.; Fitzsimmons-Craft, E.E.; Shin, K.E.; Zainal, N.H.; Schwob, J.T.; Eisenberg, D.; Wilfley, D.E.; Taylor, C.B.; Newman, M.G. College Mental Health Before and During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Results From a Nationwide Survey. Cogn. Ther. Res. 2022, 46, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ro, A.; Rodriguez, V.E.; Enriquez, L.E. Physical and mental health impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic among college students who are undocumented or have undocumented parents. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes-Portillo, J.A.; Warner, C.M.; Kline, E.; Bixter, M.T.; Chu, B.C.; Miranda, R.; Nadeem, E.; Nickerson, A.B.; Ortin Peralta, A.; Reigada, L.C.; et al. The Psychological, Academic, and Economic Impact of COVID-19 on College Students in the Epicenter of the Pandemic. Emerg. Adulthood 2022, 10, 473–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wood, C.I.; Yu, Z.; Sealy, D.A.; Moss, I.; Zigbuo-Wenzler, E.; McFadden, C.; Landi, D.; Brace, A.M. Mental Health Impacts of the COVID-19 Pandemic on College Students. J. Am. Coll. Health 2022, 72, 463–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Planas, N. COVID-19, College Academic Performance, and the Flexible Grading Policy: A Longitudinal Analysis. J. Public Econ. 2022, 207, 104606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buizza, C.; Bazzoli, L.; Ghilardi, A. Changes in College Students Mental Health and Lifestyle During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Systematic Review of Longitudinal Studies. Adolesc. Res. Rev. 2022, 7, 537–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, A.; Palomin, A.; Morales, F.R.; Sevilla-Matos, M.; Colunga Rodríguez, C.; Ángel-González, M.; Sarabia-López, L.E.; Dávalos Picazo, G.; Delgado-García, D.D.; Duclos-Bastías, D.; et al. A Cross-Sectional Study of the Mental Health Symptoms of Latin American, US Hispanic, and Spanish College Students Amid the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2023, 21, 3865–3884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turpin, R.; Rodman, A.; Matthew, L.; Watson, R.J.; Fish, J.N. Latent Syndemic Profiles among Sexual and Gender Minority College Students and Psychological Distress amid the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. LGBT Youth 2022, 20, 724–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfayumi-Zeadna, S.; Gnaim-Abu Touma, L.; Weinreich, M.; O’Rourke, N. COVID-19 and Mental Health of Minority Arab Higher-Education Students in Israel: Social, Economic, and Academic Factors. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 13466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Deng, W.; Xie, H. Differential Impact of Social Cohesion in the Lens of U.S. College Students with Different Sexual and Gender Identities on Their Mental Health during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Eur. Psychiatry 2023, 66, S122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enriquez, L.E.; Morales, A.E.; Rodriguez, V.E.; Chavarria, K.; Ro, A. Mental Health and COVID-19 Pandemic Stressors Among Latina/o/x College Students with Varying Self and Parental Immigration Status. J. Racial Ethn. Health Disparities 2023, 10, 282–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, W.; Xie, H.; Creighton, M.; Chen, J.A.; Dickerson, J.F.; Wilkins, K.M.; Garvert, D.W.; Piselli, A.; McLean, C.P.; Cochran, B.N. Patterns of Violence and Mental Health Outcomes Characterizing Vulnerability in SGM College Students before and during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Nat. Ment. Health 2023, 1, 564–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soria, K.M. Basic Needs Insecurity and College Students’ Mental Health During the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Postsecond. Stud. Success 2023, 2, 23–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J. College Students’ Mental Health Among Different Racial/Ethnic Groups. Trans. Soc. Sci. Educ. Humanit. Res. 2024, 13, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hotez, E.; Gragnani, C.M.; Fernandes, P.; Rosenau, K.A.; Wang, K.; Chopra, A.; Chow, K.; Chung, A.; Khorasani, L.; Kuo, A.A. A Mixed Methods Investigation of College Student Mental Health during the First Year of the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Am. Coll. Health 2022, 72, 1632–1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salgado, A.B.; Salgado, J.J.R.C.M.; Mathew, S.M.; Razak, A.; Hussain, S.; Fatima, W. Mental Health and Resilience of Migrant University Students in the United Arab Emirates. Emir. Med. J. 2024, 5, e02506882322935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Xu, H.D.; Lu, W.; Talwar, D. An Assessment of Mental Health Challenges of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender College Students during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Healthcare 2024, 12, 2047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, L.B.; Doyle, L.J.; Dawes, H.C.; Stulting, T.T.S.; Cruys, C.; Faccini, M.D.; Marcotte, M. The impact of COVID-19 on campus sexual and relationship violence against LGBTQ+ communities. J. Divers. High. Educ. 2024. Advance online publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Saita, K.; Kaneko, F.; Okamura, H. Stressors during the COVID-19 pandemic in international students: A qualitative study. BMC Public Health 2025, 25, 1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Han, D.; Zhang, J.; Fan, J.; Ning, P.; Peng, Y. Study on the Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on the Mental Health of Chinese College Students: A Cross-Sectional Analysis. Front. Public Health 2024, 12, 1340642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandya, A.; Lodha, P. Mental health consequences of COVID-19 pandemic among college students and coping approaches adapted by higher education institutions: A scoping review. SSM-Ment. Health 2022, 2, 100122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Author/Country/Year | Population Size/Type of Article | Outcomes and Findings Related to Review Aim |

|---|---|---|

| Campbell et al./USA/2020 [20] | USA college students (no specific population size reported)/ Research article |

|

| Lederer et al./USA/2020 [21] | USA college students (no specific population size reported)/ Research article |

|

| Rudenstine et al./USA/2021 [22] | N = 1821 university students/ Quantitative study |

|

| Lee et al./USA/2021 [23] | N = 1412 undergraduate students/ Quantitative study (online survey study) |

|

| Kim et al./USA/2021 [24] | N = 8613 college students (n = 3643 pre-pandemic, n = 4970 during pandemic)/Original quantitative study |

|

| Ro et al./USA/2021 [25] | N = 2111 California college students (undergraduates)/Quantitative study |

|

| Molock and Parchem/USA/2021 [7] | N = 193 ethnically diverse college students/ Cross-sectional survey study |

|

| Reyes-Portillo et al./USA/2022 [26] | N = 4714 college students from 55 universities in New York and New Jersey/ Online survey conducted |

|

| Wood et al./USA/2022 [27] | N = 489 U.S. college students, undergraduates/ Cross-sectional online survey |

|

| Rodríguez-Planas/ USA/2022 [28] | N ≈ 12,000 academic records/ Research study (Quantitative methods: difference-in-differences models and event study analyses) |

|

| Buizza et al./Italy/2022 [29] | N = 20,108 college students/ Systematic review of 17 longitudinal studies |

|

| Torres et al./USA/ Mexico/ Chile/ Ecuador/ Spain/ 2023 [30] | N = 1113 college students (USA, Mexico, Chile, Ecuador, Spain)/ Cross-sectional, online survey study |

|

| Turpin et al./ USA/2022 [31] | N = 565 sexual and gender minority (SGM) College students/Quantitative cross-sectional study with latent profile analysis |

|

| Alfayumi-Zeadna et al./Israel/2022 [32] | N = 420 Arab minority university students/ Cross-sectional quantitative study |

|

| Lin et al./USA/2023 [33] | N = 139,470 U.S. college students across 60 campuses/ Quantitative survey with multivariable regression |

|

| Enriquez et al./USA/2023 [34] | Ν = 1600 Latina/o/x University of California Undergraduates/ mixed-methods (quantitative and qualitative) |

|

| Deng et al./USA/2023 [35] | N ≈ 217,552 college Population (0.12% transgender women, 0.21% transgender men, and 1.97% gender-diverse individuals)/ Quantitative longitudinal study |

|

| Soria/USA/2023 [36] | N = 49,122 college students from 130 community colleges and 72 four-year institutions/ Quantitative study |

|

| Wei/USA/2024 [37] | N = 32 college students (53% Asian, 25% Asian American, 13% Hispanic/Latino, 9% White/Caucasian)/ Original quantitative study |

|

| Hotez et al./USA/2022 [38] | N = 128 (June 2020), N = 240 (December 2020); undergraduate minority students/ Mixed methods (quantitative and qualitative) |

|

| Salgado et al./ UAE/2024 [39] | N = 206 university students who migrated/ Empirical study |

|

| Xu et al./USA/2024 [40] | N = 611 university students (79% straight, 20% LGBTQ+)/ Quantitative web-based survey |

|

| Klein et al./USA/ 2024 [41] | N = 31 LGBTQ+ campus antiviolence personnel/Qualitative study (semi-structured interviews) |

|

| Ma et al./JAPAN/ 2025 [42] | N = 20 international students/ Qualitative study |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sakaretsanou, A.-K.; Bakola, M.; Chatzeli, T.; Charalambous, G.; Jelastopulu, E. Mental Health Impacts of the COVID-19 Pandemic on College Students: A Literature Review with Emphasis on Vulnerable and Minority Populations. Healthcare 2025, 13, 1572. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13131572

Sakaretsanou A-K, Bakola M, Chatzeli T, Charalambous G, Jelastopulu E. Mental Health Impacts of the COVID-19 Pandemic on College Students: A Literature Review with Emphasis on Vulnerable and Minority Populations. Healthcare. 2025; 13(13):1572. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13131572

Chicago/Turabian StyleSakaretsanou, Anna-Koralia, Maria Bakola, Taxiarchoula Chatzeli, Georgios Charalambous, and Eleni Jelastopulu. 2025. "Mental Health Impacts of the COVID-19 Pandemic on College Students: A Literature Review with Emphasis on Vulnerable and Minority Populations" Healthcare 13, no. 13: 1572. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13131572

APA StyleSakaretsanou, A.-K., Bakola, M., Chatzeli, T., Charalambous, G., & Jelastopulu, E. (2025). Mental Health Impacts of the COVID-19 Pandemic on College Students: A Literature Review with Emphasis on Vulnerable and Minority Populations. Healthcare, 13(13), 1572. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13131572