Work-Related Low Back Pain and Psychological Distress Among Physiotherapists in Saudi Arabia: A Cross-Sectional Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

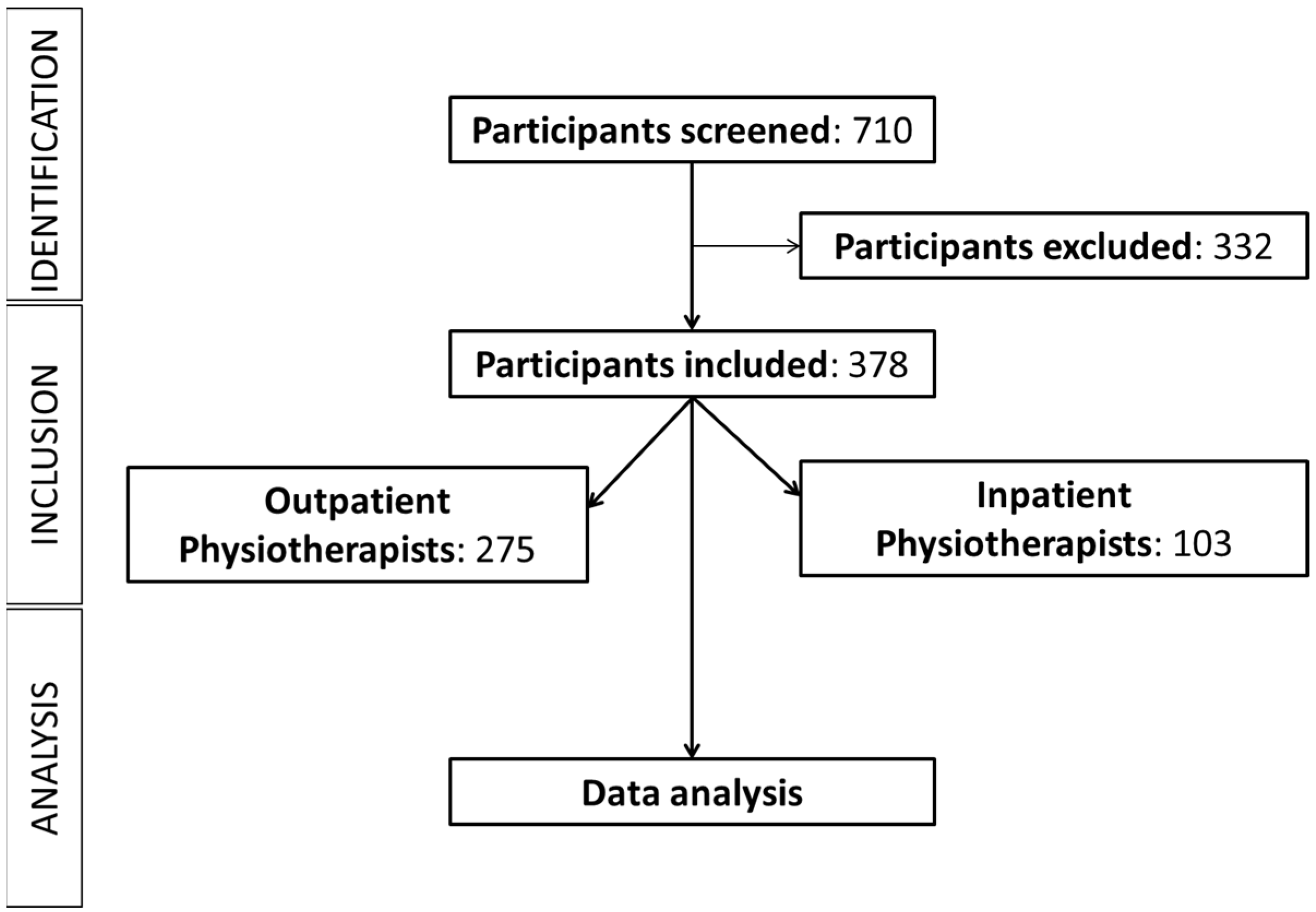

2. Methodology

2.1. Research Design

2.2. Sample Size Estimation

2.3. Participants

2.4. Procedure

2.5. Operational Definitions

2.6. Questionnaire

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sample Characteristics

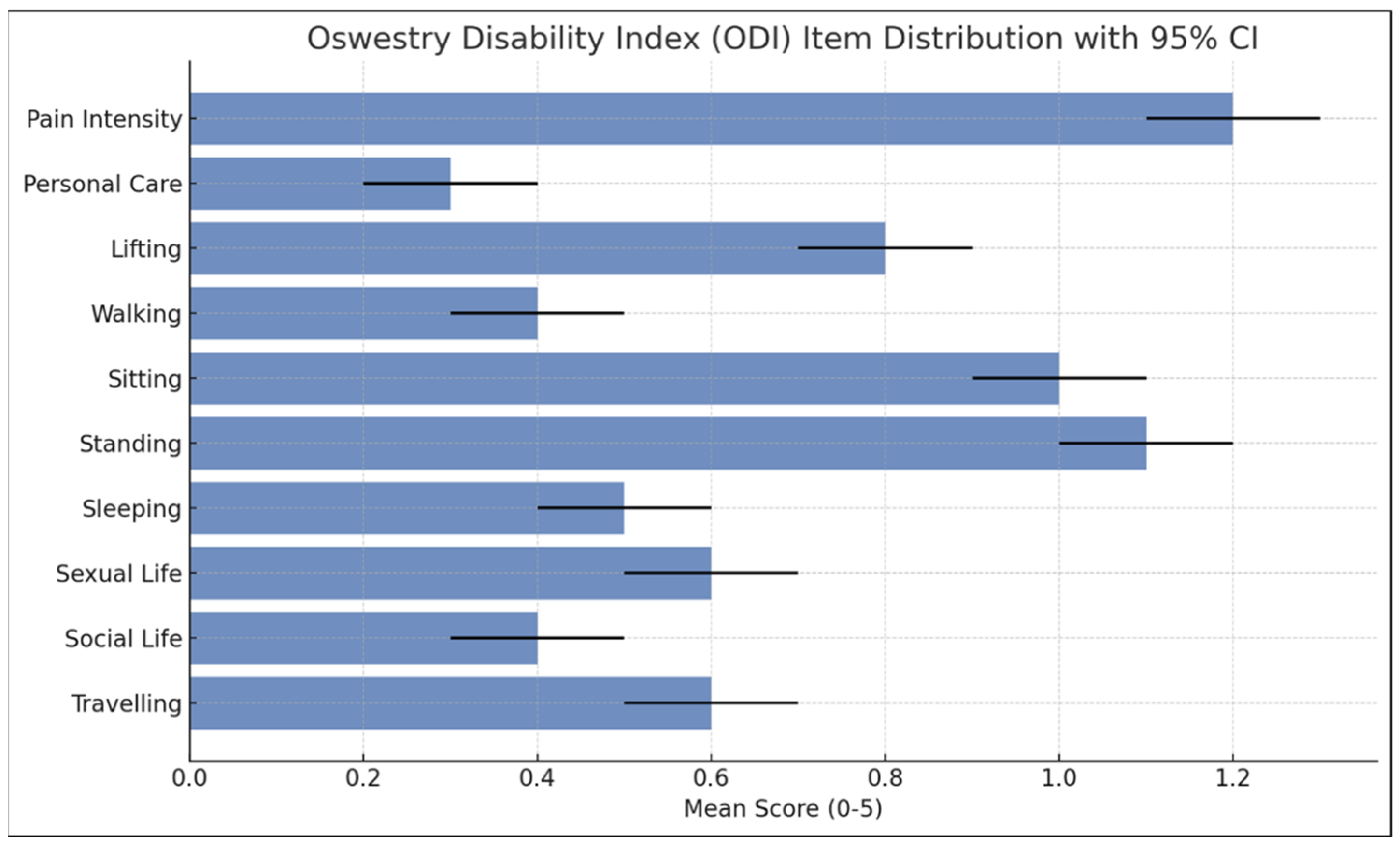

3.2. Pain Intensity and Disability

3.3. Mental Health Assessment

3.4. LBP, Psychological Distress, and Disability by Workplace Setting

3.5. Correlations Between Disability and Psychological Distress

3.6. Psychological Distress as Predictors of Low Back Pain

3.7. Work-Related Factors and LBP

4. Discussion

Limitations and Recommendations for Future Studies

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Major, M.-E.; Vézina, N. Analysis of worker strategies: A comprehensive understanding for the prevention of work related musculoskeletal disorders. Int. J. Ind. Ergon. 2015, 48, 149–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Costa, B.R.; Vieira, E.R. Risk factors for work-related musculoskeletal disorders: A systematic review of recent longitudinal studies. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2010, 53, 285–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Louw, Q.A.; Morris, L.D.; Grimmer-Somers, K. The prevalence of low back pain in Africa: A systematic review. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2007, 8, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bork, B.E.; Cook, T.M.; Rosecrance, J.C.; Engelhardt, K.A.; Thomason, M.-E.J.; Wauford, I.J.; Worley, R.K. Work-related musculoskeletal disorders among physical therapists. Phys. Ther. 1996, 76, 827–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alghadir, A.; Zafar, H.; Iqbal, Z.A. Work-related musculoskeletal disorders among dental professionals in Saudi Arabia. J. Phys. Ther. Sci. 2015, 27, 1107–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorce, P.; Jacquier-Bret, J. Global prevalence of musculoskeletal disorders among physiotherapists: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2023, 24, 265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lunde, L.-K. Physical Demands at Work: Objectively Measured Exposure and Musculoskeletal Pain in Constructionand Healthcare Workers. Thesis, University of Oslo, Oslo, Norway, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Vieira, E.R.; Schneider, P.; Guidera, C.; Gadotti, I.C.; Brunt, D. Work-related musculoskeletal disorders among physical therapists: A systematic review. J. Back Musculoskelet. Rehabil. 2016, 29, 417–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alghadir, A.; Zafar, H.; Iqbal, Z.A.; Al-Eisa, E. Work-related low back pain among physical therapists in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Workplace Health Saf. 2017, 65, 337–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trinkoff, A.M.; Lipscomb, J.A.; Geiger-Brown, J.; Storr, C.L.; Brady, B.A. Perceived physical demands and reported musculoskeletal problems in registered nurses. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2003, 24, 270–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suleiman, A.K.; Ming, L.C. Transforming healthcare: Saudi Arabia’s vision 2030 healthcare model. J. Pharm. Policy Pract. 2025, 18, 2449051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, S.; Mok, D.; Leenen, L. Transformation of health care and the new model of care in Saudi Arabia: Kingdom’s Vision 2030. J. Med. Life 2021, 14, 347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshehri, M.A.; Alhasan, H.; Alayat, M.; Al-Subahi, M.; Yaseen, K.; Ismail, A.; Tobaigy, A.; Almalki, O.; Alqahtani, A.; Fallata, B. Factors affecting the extent of utilization of physiotherapy services by physicians in Saudi Arabia. J. Phys. Ther. Sci. 2018, 30, 216–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikiru, L.; Hanifa, S. Prevalence and risk factors of low back pain among nurses in a typical Nigerian hospital. Afr. Health Sci. 2010, 10, 26. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Andersen, L.L.; Clausen, T.; Persson, R.; Holtermann, A. Perceived physical exertion during healthcare work and risk of chronic pain in different body regions: Prospective cohort study. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 2013, 86, 681–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Folkman, S. Stress: Appraisal and Coping. In Encyclopedia of Behavioral Medicine; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; pp. 1913–1915. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders; American Psychiatric Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Depression and Other Common Mental Disorders: Global Health Estimates; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Mohammed, O.; Alzahrani, H.; Marouf, E.; Shaheen, R. Physiotherapists’ perspectives on the implementation of direct access to physiotherapy services in Saudi Arabia: A cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2025, 15, e089601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iqbal, Z.; Alghadir, A. Prevalence of work-related musculoskeletal disorders among physical therapists. Med. Pracy. Work. Health Saf. 2015, 66, 459–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairbank, J.C. Oswestry disability index. J. Neurosurg. Spine 2014, 20, 239–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D. The convergent, discriminant, and nomological validity of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales-21 (DASS-21). J. Affect. Disord. 2019, 259, 136–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bijur, P.E.; Silver, W.; Gallagher, E.J. Reliability of the visual analog scale for measurement of acute pain. Acad. Emerg. Med. Off. J. Soc. Acad. Emerg. Med. 2001, 8, 1153–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alnahdi, A.H. The Arabic Oswestry Disability Index as a Unidimensional Measure: Confirmatory Factor Analysis. Spine 2025, 50, E103–E109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.M.; Ahmed, A.; Sharaf, A.; Kawakami, N.; Abdeldayem, S.M.; Green, J. The Arabic version of the depression anxiety stress scale-21: Cumulative scaling and discriminant-validation testing. Asian J. Psychiatry 2017, 30, 56–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, I.H.; Chen, C.Y.; Liao, X.L.; Chen, X.M.; Zheng, X.; Tsai, Y.C.; Lin, C.Y.; Griffiths, M.D.; Pakpour, A.H. Psychometric properties of the Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale (DASS-21) among different Chinese populations: A cross-sectional and longitudinal analysis. Acta Psychol. 2003, 240, 104042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelaziz, R.A.; AbdElnabi, H.A.; Ali, M.M.; Elsayed, N.M. Prevalence of Musculoskeletal Problems and Its Relation to Psychological Distress among General Secondary Students Subjected to Online Learning. Zagazig Nurs. J. 2024, 20, 385–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, Y.-H.; Min, K.S. Associations between work-related musculoskeletal disorders, quality of life, and workplace stress in physical therapists. Ind. Health 2016, 54, 347–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haris, M.; Bangash, N.S.; Badar, S.; Raza, K.F.; Lata, P.; Mehreen, S.; Baqir, S.R. Consequences of Stress on the Workability of Physical Therapists: Stress and Workability of Physical Therapists. THERAPIST (J. Ther. Rehabil. Sci.) 2024, 5, 56–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansour, Z.M.; Albatayneh, R.; Al-Sharman, A. Work-related musculoskeletal disorders among Jordanian physiotherapists: Prevalence and risk factors. Work 2022, 73, 1433–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikołajewski, D.; Masiak, J.; Mikołajewska, E. Selected determinants of occupational stress and burnout in physiotherapists and IT professionals. J. Educ. Health Sport 2023, 28, 62–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alghadir, A.H.; Khalid, S.; Iqbal, Z.A. Work-related musculoskeletal disorders among information technology professionals in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Med. Pracy. Work. Health Saf. 2022, 73, 397–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodman, A.; Homan, M.; Niaz, A.; Al-Jamea, L.; Akhtar, M.; Sager, M. Low back pain among healthcare personnel in Saudi Arabia: A systematic review. Ibnosina J. Med. Biomed. Sci. 2020, 12, 108–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | n = 378 |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Female | 241 (63.8%) |

| Male | 137 (36.2%) |

| Nationality | |

| Saudi | 357 (94.4%) |

| Other | 21 (5.6%) |

| Marital Status | |

| Unmarried | 241 (63.8%) |

| Married | 125 (33.1%) |

| Divorced | 10 (2.6%) |

| Widowed | 2 (0.5%) |

| BMI | |

| Normal (18.5–24.9) | 161 (42.6%) |

| Overweight (25–29.9) | 123 (32.5%) |

| Obese (>30) | 79 (20.9%) |

| Thin (<18.5) | 15 (4.0%) |

| Chronic Diseases | |

| Yes | 44 (11.6%) |

| No | 334 (88.4%) |

| Workplace Type | |

| Outpatient | 275 (72.8%) |

| Inpatient | 103 (27.2%) |

| Years of Experience | |

| 1–5 years | 253 (66.9%) |

| >5–10 years | 88 (23.3%) |

| >10 years | 37 (9.8%) |

| Duration of Pain | |

| Up to 3 days | 44 (11.6%) |

| >3 days but <3 months | 101 (26.7%) |

| >3 months but <1 year | 79 (20.9%) |

| >1 year | 154 (40.7%) |

| Measure | Mean (SD) | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|

| Pain Intensity (cm) | ||

| VAS Score (0–10) | 4.6 (1.6) | 4.4–4.8 |

| Oswestry Disability Index (ODI, score 0–5) | ||

| Pain Intensity | 1.2 (0.8) | 1.1–1.3 |

| Personal Care | 0.3 (0.5) | 0.2–0.4 |

| Lifting | 0.8 (0.9) | 0.7–0.9 |

| Walking | 0.4 (0.6) | 0.3–0.5 |

| Sitting | 1.0 (0.8) | 0.9–1.1 |

| Standing | 1.1 (0.9) | 1.0–1.2 |

| Sleeping | 0.5 (0.6) | 0.4–0.6 |

| Sexual Life | 0.6 (0.8) | 0.5–0.7 |

| Social Life | 0.4 (0.7) | 0.3–0.5 |

| Travelling | 0.6 (0.7) | 0.5–0.7 |

| Overall ODI Score (score 0–50) | 6.8 (4.7) | 6.3–7.3 |

| Disability (%) | 14.4% | 12.6–16.2% |

| Condition (n = 378) | n (%) | Mean Score (SD) | Severity Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Depression | |||

| Not Depressed | 190 (50.3%) | 10.74 (9.66) | Mild |

| Mild | 52 (13.8%) | ||

| Moderate | 80 (21.2%) | ||

| Severe | 28 (7.4%) | ||

| Extremely Severe | 28 (7.4%) | ||

| Anxiety | |||

| Normal | 183 (48.4%) | 9.57 (8.81) | Moderate |

| Mild | 33 (8.7%) | ||

| Moderate | 77 (20.4%) | ||

| Severe | 33 (8.7%) | ||

| Extremely Severe | 52 (13.8%) | ||

| Stress | |||

| Normal | 250 (66.1%) | 12.87 (9.65) | Normal |

| Mild | 41 (10.8%) | ||

| Moderate | 41 (10.8%) | ||

| Severe | 28 (7.4%) | ||

| Extremely Severe | 18 (4.8%) | ||

| (a) Prevalence of Low Back Pain by Workplace Setting (outpatient vs. inpatient). | |||||

| Workplace Setting | No Pain n (%) | Pain n (%) | Total n (%) | χ2 (1, N = 697) | p-Value |

| Outpatient | 245 (47.1%) | 275 (52.9%) | 520 (74.6%) | 1.499 | 0.221 |

| Inpatient | 74 (41.8%) | 103 (58.2%) | 177 (25.4%) | ||

| Total | 319 (45.8%) | 378 (54.2%) | 697 (100%) | ||

| (b) Disability Scores by Workplace Setting (outpatient vs. inpatient). | |||||

| Workplace Setting | n (%) | Mann-Whitney U | p-Value | ||

| Outpatient | 269 (73%) | −2.180 | 0.029 | ||

| Inpatient | 99 (27%) | ||||

| Total | 368 (100%) | ||||

| (c) Anxiety Severity by Workplace Setting (outpatient vs. inpatient). | |||||

| Severity Level | Outpatient n (%) | Inpatient n (%) | χ2 (4, N = 378) | p-Value | |

| Normal | 133 (48.3%) | 50 (48.5%) | 8.506 | 0.075 | |

| Mild | 25 (9.0%) | 8 (7.7%) | |||

| Moderate | 60 (21.8%) | 17 (16.5%) | |||

| Severe | 27 (9.8%) | 6 (5.8%) | |||

| Extremely Severe | 30 (10.9%) | 22 (21.3%) | |||

| Total | 275 (100%) | 103 (100%) | |||

| (d) Depression Severity by Workplace Setting (outpatient vs. inpatient). | |||||

| Severity Level | Outpatient n (%) | Inpatient n (%) | χ2 (4, N = 378) | p-Value | |

| Normal | 145 (52.7%) | 45 (43.6%) | 6.325 | 0.176 | |

| Mild | 40 (14.5%) | 12 (11.6%) | |||

| Moderate | 50 (18.1%) | 30 (29.1%) | |||

| Severe | 19 (6.9%) | 9 (8.7%) | |||

| Extremely Severe | 21 (7.6%) | 7 (6.8%) | |||

| Total | 275 (100%) | 103 (100%) | |||

| (e) Stress Severity by Workplace Setting (outpatient vs. inpatient). | |||||

| Severity Level | Outpatient n (%) | Inpatient n (%) | χ2 (4, N = 378) | p-Value | |

| Normal | 185 (67.2%) | 65 (63.1%) | 3.119 | 0.538 | |

| Mild | 28 (10.1%) | 13 (12.6%) | |||

| Moderate | 26 (9.4%) | 15 (14.5%) | |||

| Severe | 22 (8.0%) | 6 (5.8%) | |||

| Extremely Severe | 14 (5.1%) | 4 (3.8%) | |||

| Total | 275 (100%) | 103 (100%) | |||

| Model | R2 | F-Value | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inpatient Department (n = 103) | |||

| Anxiety (Univariate) | 0.207 | 27.685 | <0.001 |

| Depression (Univariate) | 0.216 | 29.048 | <0.001 |

| Stress (Univariate) | 0.248 | 34.575 | <0.001 |

| Multivariate Model (Anxiety + Depression + Stress + Age + BMI + Experience) | 0.293 | 10.883 | <0.001 |

| Outpatient Department (n = 275) | |||

| Anxiety (Univariate) | 0.111 | 35.254 | <0.001 |

| Depression (Univariate) | 0.090 | 28.035 | <0.001 |

| Stress (Univariate) | 0.131 | 42.457 | <0.001 |

| Multivariate Model (Anxiety + Depression + Stress + Age + BMI + Experience) | 0.178 | 11.302 | <0.001 |

| Overall Sample (n = 378) | |||

| Anxiety (Univariate) | 0.143 | 64.064 | <0.001 |

| Depression (Univariate) | 0.125 | 54.882 | <0.001 |

| Stress (Univariate) | 0.132 | 74.106 | <0.001 |

| Multivariate Model (Anxiety + Depression + Stress + Age + BMI + Experience) | 0.198 | 15.842 | <0.001 |

| Work-Related Factor (n = 378) | Chi-Square | p-Value |

|---|---|---|

| Department Type | χ2 (2, N = 378) = 1.582 | 0.453 |

| Years of Experience | χ2 (4, N = 378) = 2.562 | 0.634 |

| Work Hours | χ2 (14, N = 378) = 7.045 | 0.933 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alsenan, A.A.; Seyam, M.K.; Shawky, G.M.; Atya, A.M.; Abdel Ghafar, M.A.; Hasan, S. Work-Related Low Back Pain and Psychological Distress Among Physiotherapists in Saudi Arabia: A Cross-Sectional Study. Healthcare 2025, 13, 1853. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13151853

Alsenan AA, Seyam MK, Shawky GM, Atya AM, Abdel Ghafar MA, Hasan S. Work-Related Low Back Pain and Psychological Distress Among Physiotherapists in Saudi Arabia: A Cross-Sectional Study. Healthcare. 2025; 13(15):1853. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13151853

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlsenan, Amjad Abdullah, Mohamed K. Seyam, Ghada M. Shawky, Azza M. Atya, Mohamed A. Abdel Ghafar, and Shahnaz Hasan. 2025. "Work-Related Low Back Pain and Psychological Distress Among Physiotherapists in Saudi Arabia: A Cross-Sectional Study" Healthcare 13, no. 15: 1853. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13151853

APA StyleAlsenan, A. A., Seyam, M. K., Shawky, G. M., Atya, A. M., Abdel Ghafar, M. A., & Hasan, S. (2025). Work-Related Low Back Pain and Psychological Distress Among Physiotherapists in Saudi Arabia: A Cross-Sectional Study. Healthcare, 13(15), 1853. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13151853