Prevalence and Impact of Antidepressant and Anti-Anxiety Use Among Saudi Medical Students: A National Cross-Sectional Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Ethical Approval

2.2. Study Design and Participants

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Instruments

2.5. Survey Validity and Reliability

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sociodemographic Data

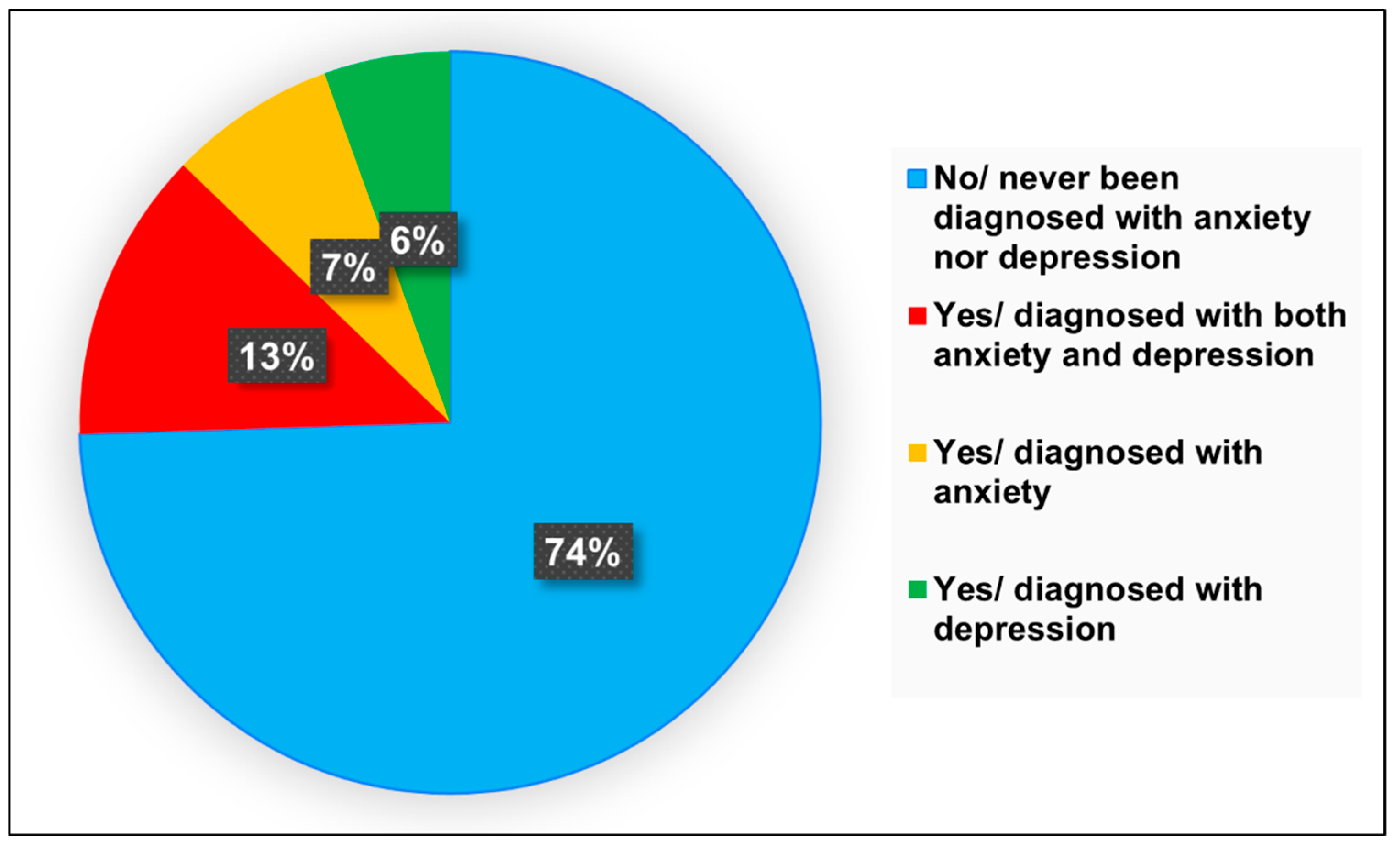

3.2. Understanding Anxiety and Depression Among Medical Students

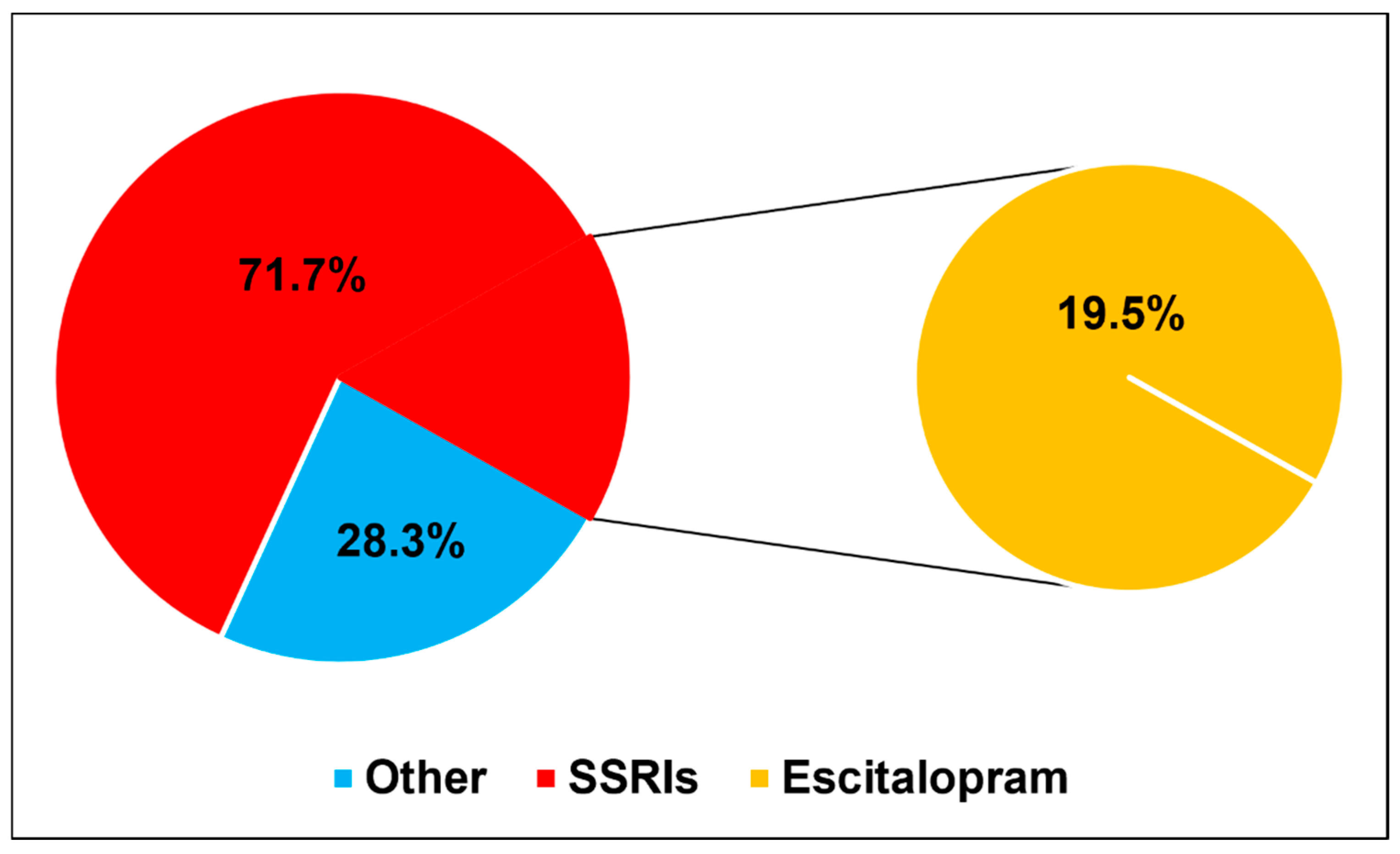

3.3. Anti-Anxiety and Antidepressant Medication Usage and Perceptions

3.4. Associations of Anti-Anxiety and Antidepressant Medication Use with Sociodemographic Data

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Ibrahim, A.K.; Kelly, S.J.; Adams, C.E.; Glazebrook, C. A systematic review of studies of depression prevalence in university students. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2013, 47, 391–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotenstein, L.S.; Ramos, M.A.; Torre, M.; Segal, J.B.; Peluso, M.J.; Guille, C.; Sen, S.; Mata, D.A. Prevalence of depression, depressive symptoms, and suicidal ideation among medical students: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2016, 316, 2214–2236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brenneisen Mayer, F.; Souza Santos, I.; Silveira, P.S.; Itaqui Lopes, M.H.; de Souza, A.R.N.D.; Campos, E.P.; de Abreu, B.A.L.; Hoffman, I., II; Magalhães, C.R.; Lima, M.C.P. Factors associated to depression and anxiety in medical students: A multicenter study. BMC Med. Educ. 2016, 16, 282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pacheco, J.P.; Giacomin, H.T.; Tam, W.W.; Ribeiro, T.B.; Arab, C.; Bezerra, I.M.; Pinasco, G.C. Mental health problems among medical students in Brazil: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Braz. J. Psychiatry 2017, 39, 369–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, S.G.; Kattimani, S.; Sarkar, S.; Kar, S.S. Prevalence of depression and its relation to stress level among medical students in Puducherry, India. Ind. Psychiatry J. 2017, 26, 86–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köhler, C.A.; Evangelou, E.; Stubbs, B.; Solmi, M.; Veronese, N.; Belbasis, L.; Bortolato, B.; Melo, M.C.; Coelho, C.A.; Fernandes, B.S. Mapping risk factors for depression across the lifespan: An umbrella review of evidence from meta-analyses and Mendelian randomization studies. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2018, 103, 189–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puthran, R.; Zhang, M.W.; Tam, W.W.; Ho, R.C. Prevalence of depression amongst medical students: A meta-analysis. Med. Educ. 2016, 50, 456–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlJaber, M.I. The prevalence and associated factors of depression among medical students of Saudi Arabia: A systematic review. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 2020, 9, 2608–2614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroenke, K.; Taylor-Vaisey, A.; Dietrich, A.J.; Oxman, T.E. Interventions to Improve Provider Diagnosis and Treatment of Mental Disorders in Primary Care: A Critical Review of the Literature. Psychosomatics 2000, 41, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guthrie, E.; Black, D.; Shaw, C.; Hamilton, J.; Creed, F.; Tomenson, B. Embarking upon a medical career: Psychological morbidity in first year medical students. Med. Educ. 1995, 29, 337–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chew-Graham, C.A.; Rogers, A.; Yassin, N. ‘I wouldn’t want it on my CV or their records’: Medical students’ experiences of help-seeking for mental health problems. Med. Educ. 2003, 37, 873–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goebert, D.; Thompson, D.; Takeshita, J.; Beach, C.; Bryson, P.; Ephgrave, K.; Kent, A.; Kunkel, M.; Schechter, J.; Tate, J. Depressive symptoms in medical students and residents: A multischool study. Acad. Med. 2009, 84, 236–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fond, G.; Bourbon, A.; Lançon, C.; Boucekine, M.; Micoulaud-Franchi, J.; Auquier, P.; Boyer, L. Psychiatric and psychological follow-up of undergraduate and postgraduate medical students: Prevalence and associated factors. Results from the national BOURBON study. Psychiatry Res. 2019, 272, 425–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fond, G.; Bourbon, A.; Boucekine, M.; Messiaen, M.; Barrow, V.; Auquier, P.; Lançon, C.; Boyer, L. First-year French medical students consume antidepressants and anxiolytics while second-years consume non-medical drugs. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 265, 71–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdallat, M.; Murshidi, R.; Taha, H.; Jaber, D.Z.; Hammouri, M.; Al-Huneidy, L.; Aljayeh, M.; Ghanem, H.H.; Bedros, A.W.; Al-Omairi, J. An investigation of knowledge and attitudes towards antidepressants: A cross-sectional survey of Jordan’s six medical schools. BMC Psychiatry 2023, 23, 604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramic, E.; Prasko, S.; Gavran, L.; Spahic, E. Assessment of the antidepressant side effects occurrence in patients treated in primary care. Mater. Socio-Medica 2020, 32, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheffler, Z.M.; Patel, P.; Abdijadid, S. Antidepressants. In StatPearls [internet]; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Simon, L.V.; Torrico, T.J.; Keenaghan, M. Serotonin syndrome. In StatPearls [Internet]; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Eugene, A.R. Country-specific psychopharmacological risk of reporting suicidality comparing 38 antidepressants and lithium from the FDA Adverse Event Reporting System, 2017–2023. Front. Psychiatry 2024, 15, 1442490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braund, T.A.; Tillman, G.; Palmer, D.M.; Gordon, E.; Rush, A.J.; Harris, A.W. Antidepressant side effects and their impact on treatment outcome in people with major depressive disorder: An iSPOT-D report. Transl. Psychiatry 2021, 11, 417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhave, S.; Nagpal, J. Anxiety and depressive disorders in college youth. Pediatr. Clin. 2005, 52, 97–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auerbach, R.P.; Mortier, P.; Bruffaerts, R.; Alonso, J.; Benjet, C.; Cuijpers, P.; Demyttenaere, K.; Ebert, D.D.; Green, J.G.; Hasking, P. WHO world mental health surveys international college student project: Prevalence and distribution of mental disorders. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2018, 127, 623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.; Schommer, J.; Worley, M.; Peden-McAlpine, C. Antidepressant Use Amongst College Students: Findings of a Phenomenological Study. Innov. Pharm. 2012, 3, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hammonds, T.; Rickert, K.; Goldstein, C.; Gathright, E.; Gilmore, S.; Derflinger, B.; Bennett, B.; Sterns, A.; Drew, B.L.; Hughes, J.W. Adherence to antidepressant medications: A randomized controlled trial of medication reminding in college students. J. Am. Coll. Health 2015, 63, 204–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morris, M.R.; Hoeflich, C.C.; Nutley, S.; Ellingrod, V.L.; Riba, M.B.; Striley, C.W. Use of psychiatric medication by college students: A decade of data. Pharmacotherapy 2021, 41, 350–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hope, V.; Henderson, M. Medical student depression, anxiety and distress outside North America: A systematic review. Med. Educ. 2014, 48, 963–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aamir, I.S. Stress Level Comparison of Medical and Nonmedical Students: A Cross Sectional Study done at Various Professional Colleges in Karachi, Pakistan. Acta Psychopathol. 2017, 3, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maser, B.; Danilewitz, M.; Guérin, E.; Findlay, L.C.; Frank, E. Medical Student Psychological Distress and Mental Illness Relative to the General Population: A Canadian Cross-Sectional Survey. Acad. Med. 2019, 94, 1781–1791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuttilan, A.N.; Sayampanathan, A.A.; Ho, R.C.-M. Mental health issues amongst medical students in Asia: A systematic review [2000–2015]. Ann. Transl. Med. 2016, 4, 72. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, A.M.K.; Moon, J.E.; Friedman, R.A. Meeting the challenges of medical student mental health and well-being today. Med. Educ. 2020, 54, 183–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, M.S.; Steelesmith, D.L.; Brock, G.; Benedict, J.; Muñoz, J.; Fontanella, C.A. Mental health service utilization among medical students with a perceived need for care. Acad. Psychiatry 2022, 46, 223–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rich, A.; Viney, R.; Silkens, M.E.W.M.; Griffin, A.; Medisauskaite, A. The experiences of students with mental health difficulties at medical school: A qualitative interview study. Med. Educ. Online 2024, 29, 2366557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fasanella, N.A.; Custódio, C.G.; Cabo, J.S.d.; Andrade, G.S.; Almeida, F.A.d.; Pavan, M.V. Use of prescribed psychotropic drugs among medical students and associated factors: A cross-sectional study. São Paulo Med. J. 2022, 140, 697–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radi, U.K.; Abdul-Hussein, A.H.; Hussein, U.; Hussein, U.A.-R.; Osman, T. Prevalence of depression and the use of antidepressants among Iraqi medical students. Int. J. Med. Toxicol. Leg. Med. 2024, 27. Available online: https://ijmtlm.com/index.php/journal/article/view/833642 (accessed on 18 June 2025).

- Alosaimi, F.D.; Alruwais, F.S.; Alanazi, F.A.; Alabidi, G.A.; Aljomah, N.A.; Alsalameh, N.S. Patients reasons for obtaining psychotropic medications without a prescription at retail pharmacies in Central Saudi Arabia. Neurosciences 2016, 21, 338–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balıkçı, A.; Uzun, Ö.; Erdem, M.; Doruk, A.; Cansever, A.; Ateş, M.A. Side effects that Cause Noncompliance to Antidepressant Medications in the Course of Outpatient Treatment. Klin. Psikofarmakol. Bul.-Bull. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2014, 24, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Shahi, U.B.; Acharya, A.; Timalsina, S.; Gautam, A.; Swain, K.C.; Panthi, S. Study of Adverse Drug Reaction of Anti-Depressants in Adult Patients: A Nepalese Perspective. Psychiatry Int. 2023, 4, 220–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkhowaiter, S.S.; Alshahrani, A.H.; Almarzouqi, H.F.; Alonazi, G.K.; Alhawassi, T.M.; AlRasheed, M.M. Feasibility, and barriers to use escitalopram in functional gastrointestinal disorders. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14, 1131354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bermudez, M.B.; Costanzi, M.; Macedo, M.J.d.A.; Tatton-Ramos, T.P.; Xavier, A.C.M.; Ferrão, Y.A.; Bentley, K.H.; Manfro, G.G.; Dreher, C.B. Improved quality of life and reduced depressive symptoms in medical students after a single-session intervention. Braz. J. Psychiatry 2019, 42, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishak, W.W.; Steiner, A.J.; Klimowicz, A.; Kauzor, K.E.; Dang, J.; Vanle, B.; Elzahaby, C.; Reid, M.W.; Sumner, L.A.; Danovitch, I. Major Depression Comorbid with Medical Conditions: Analysis of Quality of Life, Functioning, and Depressive Symptom Severity. Psychopharmacol. Bull. 2018, 48, 8–25. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ishak, W.W.; James, D.M.; Mirocha, J.M.; Youssef, H.; Tobia, G.; Pi, S.; Collison, K.L.; Cohen, R.M. Patient-reported functioning in major depressive disorder. Ther. Adv. Chronic Dis. 2016, 7, 160–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kremer, S.; Wiesinger, T.; Bschor, T.; Baethge, C. Antidepressants and Social Functioning in Patients with Major Depressive Disorder: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled RCTs. Psychother. Psychosom. 2023, 92, 304–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Khani, A.M.; Sarhandi, M.I.; Zaghloul, M.S.; Ewid, M.; Saquib, N. A cross-sectional survey on sleep quality, mental health, and academic performance among medical students in Saudi Arabia. BMC Res. Notes 2019, 12, 665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpi, M.; Vestri, A. The Mediating Role of Sleep Quality in the Relationship between Negative Emotional States and Health-Related Quality of Life among Italian Medical Students. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 20, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayed, H.B.; Yaich, S.; Jemaa, M.B.; Hmida, M.B.; Trigui, M.; Jedidi, J.; Karray, R.; Mejdoub, Y.; Feki, H.; Kassis, M.; et al. Lifestyle behaviors and mental health in medical students. J. Public Ment. Health 2018, 17, 210–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Ayed, H.; Jedidi, J.; Cheikhrouhou, F.; Ayadi, A.; Yaich, S.; Damak, J. Are lifestyle behaviors correlated to mental health disorders in medical students? Eur. J. Public Health 2019, 29 (Suppl. S4), ckz185-022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vollmer-Conna, U.; Beilharz, J.E.; Cvejic, E.; Macnamara, C.L.; Doherty, M.; Steel, Z.; Hadzi-Pavlovic, D.; Harvey, S.B.; Parker, G. The well-being of medical students: A biopsychosocial approach. Aust. New Zealand J. Psychiatry 2020, 54, 997–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razouk, O. Assessing the Factors Affecting Health-Related Quality of Life in Medical Students. Res. Int. J. Community Med. Public Health 2024, 3, 5–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tjia, J.; Givens, J.L.; Shea, J.A. Factors Associated With Undertreatment of Medical Student Depression. J. Am. Coll. Health 2005, 53, 219–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, M.S.; Mahmood, S.; Badshah, A.; Ali, S.U.; Jamal, Y.S. Prevalence of depression, anxiety and their associated factors among medical students in Karachi, Pakistan. JPMA J. Pak. Med. Assoc. 2006, 56, 583–586. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kadhim, S.N.; Ahmed, Z.H.; Abdulsahib, M.L. Anxiety, depression, and psychotropic drugs usage by university students of medical group in Basra, Iraq. Univers. J. Pharm. Res. 2024, 9, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carletto, S.; Miniotti, M.; Persico, A.; Leombruni, P. Emotional distress and psychiatric drug use among students in an Italian medical school: Assessing the role of gender and year of study. J. Educ. Health Promot. 2021, 10, 451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fond, G.; Bourbon, A.; Auquier, P.; Micoulaud-Franchi, J.-A.; Lançon, C.; Boyer, L. Venus and Mars on the benches of the faculty: Influence of gender on mental health and behavior of medical students. Results from the BOURBON national study. J. Affect. Disord. 2018, 239, 146–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bojanić, I.; Sund, E.R.; Bjerkeset, O.; Sivertsen, B.; Sletvold, H. Psychological Distress and Use of Psychotropic Drugs Among University Students—The SHoT Study, Norway. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 717955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hardeman, R.R.; Przedworski, J.M.; Burke, S.E.; Burgess, D.J.; Phelan, S.M.; Dovidio, J.F.; Nelson, D.B.; Rockwood, T.; Ryn, M. Mental Well-Being in First Year Medical Students: A Comparison by Race and Gender. J. Racial Ethn. Health Disparities 2015, 2, 403–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacob, L.; Kostev, K. Gender-based differences in the antidepressant treatment of patients with depression in German psychiatric practices. GMS Ger. Med. Sci. 2016, 14, Doc02. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Seifert, J.; Führmann, F.; Reinhard, M.A.; Engel, R.R.; Bernegger, X.; Bleich, S.; Stübner, S.; Rüther, E.; Toto, S.; Grohmann, R. Sex differences in pharmacological treatment of major depressive disorder: Results from the AMSP pharmacovigilance program from 2001 to 2017. J. Neural Transm. 2021, 128, 827–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Parameter | Characteristic | Frequency n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 160 (28.5) |

| Female | 401 (71.5) | |

| Age | 18–20 | 190 (33.9) |

| 21–25 | 352 (62.7) | |

| 26–30 | 17 (3.0) | |

| Over 30 Years old | 2 (0.4) | |

| Location | North area | 14 (2.5) |

| South area | 71 (12.7) | |

| East area | 49 (8.7) | |

| West area | 239 (42.6) | |

| Center “Middle” area | 188 (33.5) | |

| University | Taif University | 46 (8.2) |

| King Abdulaziz University | 35 (6.2) | |

| University of Jeddah | 20 (3.6) | |

| AlRayan Colleges | 7 (1.2) | |

| Al-Baha University | 74 (13.2) | |

| Ummul Qura University—Makkah | 111 (19.8) | |

| King Saud bin Abdulaziz University for Health Sciences (KSAU-HS)—Riyadh | 113 (20.1) | |

| King Saud bin Abdulaziz University for Health Sciences—Jeddah | 23 (4.1) | |

| Other | 132 (23.5) | |

| Academic year | First year | 125 (22.3) |

| Second year | 53 (9.4) | |

| Third year | 69 (12.3) | |

| Fourth year | 83 (14.8) | |

| Fifth year | 92 (16.4) | |

| Sixth year | 45 (8.0) | |

| Intern | 94 (16.8) | |

| Rate of academic year performance | Poor | 20 (3.6) |

| Fair | 33 (5.9) | |

| Good | 146 (26.0) | |

| Very Good | 189 (33.7) | |

| Excellent | 173 (30.8) | |

| Educational level of mother | Not educated | 22 (3.9) |

| School | 109 (19.4) | |

| High diploma | 48 (8.6) | |

| Bachelors | 301 (53.7) | |

| Master | 55 (9.8) | |

| PhD | 26 (4.6) | |

| Educational level of father | Not educated | 14 (2.5) |

| School | 98 (17.5) | |

| High diploma | 55 (9.8) | |

| Bachelors | 243 (43.3) | |

| Master | 75 (13.4) | |

| PhD | 76 (13.5) | |

| Socioeconomic status | Upper class | 17 (3.0) |

| Upper-middle class | 201 (35.8) | |

| Lower-middle class | 43 (7.7) | |

| Middle class | 291 (51.9) | |

| Lower class | 9 (1.6) | |

| How many hours per day do you sleep? | 6 h or less | 139 (24.8) |

| 6–8 h | 286 (51.0) | |

| 8–10 h | 110 (19.6) | |

| More than 10 h | 26 (4.6) | |

| How often do you engage in exercise or physical activity per week? | None | 234 (41.7) |

| 1–2 times per week | 194 (34.6) | |

| 3–4 times per week | 102 (18.2) | |

| 5 or more times per week | 31 (5.5) | |

| Is there a family history of psychiatric disease? | No | 395 (70.4) |

| Yes | 166 (29.6) | |

| Do you smoke cigarettes? | No | 537 (95.7) |

| Yes | 24 (4.3) | |

| Do you smoke a water-pipe (Shisha)? | No | 529 (94.3) |

| Sometimes | 26 (4.6) | |

| Yes | 6 (1.1) |

| Parameter | Category | Frequency n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| What type of depression do you have? | Unsure | 31 (23.1) |

| Bipolar Disorder (Manic Depression) | 5 (3.7) | |

| Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) | 52 (38.8) | |

| Situational Depression (Triggered by specific life events) | 7 (5.2) | |

| Borderline personality disorder with histrionic personality traits | 2 (1.5) | |

| Psychotic Depression | 2 (1.5) | |

| Atypical Depression | 2 (1.5) | |

| None of the above. | 22 (16.4) | |

| Other | 11 (8.2) | |

| What type of anxiety do you have? | Unsure | 26 (20.3) |

| Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD) | 59 (46.1) | |

| Social Anxiety Disorder (Social Phobia) | 6 (4.7) | |

| Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (OCD) | 8 (6.3) | |

| Panic Disorder | 12 (9.4) | |

| Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) | 3 (2.3) | |

| None of above | 11 (8.6) | |

| Other | 3 (2.3) | |

| What specific symptoms of anxiety or depression are you currently experiencing? | Persistent feelings of sadness or emptiness | 88 (61.5) |

| Difficulty sleeping or excessive sleeping | 94 (65.7) | |

| Difficulty concentrating or making decisions | 89 (62.2) | |

| Persistent physical symptoms that do not have a clear medical cause | 46 (32.2) | |

| Loss of interest or pleasure in activities once enjoyed | 93 (65.0) | |

| Changes in appetite or weight | 77 (53.8) | |

| Fatigue or loss of energy | 101 (70.6) | |

| Feelings of worthlessness or excessive guilt | 72 (50.3) | |

| Thoughts of death or suicide | 55 (38.5) | |

| Excessive worry or rumination | 62 (43.4) | |

| Muscle tension or physical symptoms of anxiety (e.g., trembling) | 54 (37.8) | |

| Panic attacks or sudden intense fear | 51 (35.7) | |

| Palpitations (heart palpitations or irregular heartbeat) | 55 (38.5) | |

| Restlessness or irritability | 74 (51.7) | |

| Racing thoughts or mind going blank | 60 (42.0) | |

| Sweating (excessive sweating, especially without physical exertion) | 35 (24.5) | |

| Do you feel that the anxiety or depression has influenced your academic performance? | No impact | 14 (9.8) |

| Slightly impacted | 16 (11.2) | |

| Moderately impacted | 36 (25.2) | |

| Significantly impacted | 77 (53.8) | |

| Have you ever experienced suicidal thoughts or attempted suicide? | No | 60 (42.0) |

| Yes, suicidal thoughts | 62 (43.4) | |

| Yes, attempted suicide | 21 (14.7) | |

| Have you sought help or support for your mental health? | No/not considering seeking support | 4 (2.8) |

| No/considering seeking support | 16 (11.2) | |

| Psychiatric evaluation/medication management | 79 (55.2) | |

| Counseling therapy | 29 (20.3) | |

| Friends or colleagues support | 3 (2.1) | |

| Family support | 12 (8.4) | |

| What do you believe are the primary reasons for anxiety or depression among medical students? | Difficulty of study | 93 (65.0) |

| High workload | 93 (65.0) | |

| Sleep deprivation | 80 (55.9) | |

| Pressure to perform well academically | 114 (79.7) | |

| Pressure to excel in clinical rotations | 63 (44.1) | |

| Balancing personal and professional life | 80 (55.9) | |

| Financial concerns or debt | 45 (31.5) | |

| Isolation or lack of social support | 77 (53.8) | |

| Perfectionism | 91 (63.6) | |

| Witnessing or experiencing traumatic events in clinical settings | 25 (17.5) | |

| Fear of failure | 114 (79.7) | |

| Lack of exercise or physical activity | 53 (37.1) | |

| Family issues | 78 (54.5) | |

| Relationship issues | 56 (39.2) | |

| Concerns about future career prospects | 78 (54.5) | |

| Discrimination or stigma within the medical community | 39 (27.3) | |

| Substance abuse or addiction | 13 (9.1) | |

| Genetic predisposition or family history of depression | 54 (37.8) | |

| Chronic diseases (e.g., diabetes, autoimmune disorders) | 25 (17.5) |

| Parameter | Category | Frequency n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Are you currently using anti-anxiety and/or antidepressant medications? | No | 81 (56.6) |

| Yes/currently using antidepressant medications | 34 (23.8) | |

| Yes/currently using anti-anxiety medications | 8 (5.6) | |

| Yes/currently using both antidepressant and anti-anxiety medications | 20 (14.0) | |

| If yes, what is the name or class of the anti-anxiety and/or antidepressant medications you are currently using? | SSRIs | 43 (71.7) |

| Other | 17 (28.3) | |

| How do you obtain anti-anxiety and/or antidepressant medications? | No medication used | 45 (31.5) |

| From a friend or family member | 4 (2.8) | |

| Bought over-the-counter | 5 (3.5) | |

| Prescribed by a healthcare professional | 89 (62.2) | |

| How long have you been using anti-anxiety and/or antidepressants? | No medication used | 45 (31.5) |

| Less than 6 months | 39 (27.3) | |

| 6 months to 1 year | 21 (14.7) | |

| 1–2 years | 16 (11.2) | |

| More than 2 years | 22 (15.4) | |

| Have you experienced any side effects from anti-anxiety and/or antidepressant medications? | No | 42 (41.2) |

| Yes | 60 (58.8) | |

| Have you ever changed anti-anxiety and/or antidepressant medications due to inefficiency or side effects? | No | 61 (60.4) |

| Yes | 40 (39.6) | |

| Have you ever stopped taking anti-anxiety and/or antidepressant medication without consulting a healthcare professional? | No | 52 (51.0) |

| Yes | 50 (49.0) | |

| Do you feel that anti-anxiety and/or antidepressant medications have influenced your academic performance? | No | 38 (38.0) |

| Yes | 62 (62.0) | |

| Have you been compliant with your anti-anxiety and/or antidepressant medications regimen? | No | 44 (44.4) |

| Yes | 55 (55.6) | |

| The positive effects of anti-anxiety and/or antidepressants outweigh the negative effects. | Disagree | 38 (26.6) |

| Agree | 105 (73.4) | |

| Using anti-anxiety and/or antidepressants makes individuals feel strange or “doped up.” | Disagree | 62 (43.4) |

| Agree | 81 (56.6) | |

| If require anti-anxiety and/or antidepressants, I would take them willingly. | Disagree | 34 (23.8) |

| Agree | 109 (76.2) | |

| Antidepressants induce feelings of relaxation. | Disagree | 48 (33.6) |

| Agree | 95 (66.4) | |

| Anti-anxiety and/or antidepressants cause feelings of tiredness and sluggishness. | Disagree | 62 (43.4) |

| Agree | 81 (56.6) | |

| Anti-anxiety and/or antidepressants are only taken when feeling unwell. | Disagree | 106 (74.1) |

| Agree | 37 (25.9) | |

| Anti-anxiety and/or antidepressants make individuals feel normal. | Disagree | 56 (39.2) |

| Agree | 87 (60.8) | |

| It feels unnatural for one’s mind and body to be controlled by anti-anxiety and/or antidepressants. | Disagree | 75 (52.4) |

| Agree | 68 (47.6) | |

| Those who take anti-anxiety and/or antidepressants experience clearer thoughts. | Disagree | 55 (38.5) |

| Agree | 88 (61.5) | |

| Anti-anxiety and/or antidepressants can prevent individuals from experiencing a mental breakdown. | Disagree | 32 (22.4) |

| Agree | 111 (77.6) |

| Parameter | Category | No Frequency n (%) | Yes/Currently Using Antidepressant Medications Frequency n (%) | Yes/Currently Using Anti-anxiety Medications Frequency n (%) | Yes/Currently Using Both Antidepressant and Anti-anxiety Medications Frequency n (%) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 17 (50.0) | 11 (32.4) | 2 (5.9) | 4 (11.8) | 0.595 |

| Female | 64 (58.7) | 23 (21.1) | 6 (5.5) | 16 (14.7) | ||

| Age | 18–20 | 20 (71.4) | 6 (21.4) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (7.1) | 0.488 |

| 21–25 | 58 (54.2) | 24 (22.4) | 8 (7.5) | 17 (15.9) | ||

| 26–30 | 2 (33.3) | 3 (50.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (16.7) | ||

| Over 30 Years old | 1 (50.0) | 1 (50.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Location | North area | 4 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0.805 |

| South area | 15 (65.2) | 5 (21.7) | 1 (4.3) | 2 (8.7) | ||

| East area | 8 (50.0) | 5 (31.3) | 1 (6.3) | 2 (12.5) | ||

| West area | 24 (49.0) | 15 (30.6) | 2 (4.1) | 8 (16.3) | ||

| Center “Middle” area | 30 (58.8) | 9 (17.6) | 4 (7.8) | 8 (15.7) | ||

| University | Taif University | 6 (40.0) | 6 (40.0) | 1 (6.7) | 2 (13.3) | 0.116 |

| King Abdulaziz University | 6 (40.0) | 7 (46.7) | 1 (6.7) | 1 (6.7) | ||

| University of Jeddah | 3 (60.0) | 1 (20.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (20.0) | ||

| Al-Baha University | 17 (73.9) | 2 (8.7) | 1 (4.3) | 3 (13.0) | ||

| Ummul Qura University—Makkah | 9 (90.0) | 1 (10.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| King Saud bin Abdulaziz University for Health Sciences (KSAU-HS)—Riyadh | 17 (56.7) | 6 (20.0) | 4 (13.3) | 3 (10.0) | ||

| King Saud bin Abdulaziz University For Health Sciences—Jeddah | 1 (16.7) | 3 (50.0) | 1 (16.7) | 1 (16.7) | ||

| Other | 22 (56.4) | 8 (20.5) | 0 (0.0) | 9 (23.1) | ||

| Academic year | First year | 9 (69.2) | 3 (23.1) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (7.7) | 0.527 |

| Second year | 6 (46.2) | 5 (38.5) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (15.4) | ||

| Third year | 9 (47.4) | 5 (26.3) | 1 (5.3) | 4 (21.1) | ||

| Fourth year | 15 (75.0) | 1 (5.0) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (20.0) | ||

| Fifth year | 15 (50.0) | 6 (20.0) | 3 (10.0) | 6 (20.0) | ||

| Sixth year | 8 (53.3) | 4 (26.7) | 1 (6.7) | 2 (13.3) | ||

| Intern | 19 (57.6) | 10 (30.3) | 3 (9.1) | 1 (3.0) | ||

| Academic performance | Poor | 3 (30.0) | 4 (40.0) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (30.0) | 0.368 |

| Fair | 10 (58.8) | 5 (29.4) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (11.8) | ||

| Good | 19 (48.7) | 12 (30.8) | 4 (10.3) | 4 (10.3) | ||

| Very Good | 26 (59.1) | 8 (18.2) | 2 (4.5) | 8 (18.2) | ||

| Excellent | 23 (69.7) | 5 (15.2) | 2 (6.1) | 3 (9.1) | ||

| Educational level of mother | Not educated | 3 (42.9) | 3 (42.9) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (14.3) | 0.496 |

| School | 16 (50.0) | 9 (28.1) | 1 (3.1) | 6 (18.8) | ||

| High diploma | 6 (66.7) | 2 (22.2) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (11.1) | ||

| Bachelors | 45 (61.6) | 14 (19.2) | 7 (9.6) | 7 (9.6) | ||

| Master | 9 (60.0) | 4 (26.7) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (13.3) | ||

| PhD | 2 (28.6) | 2 (28.6) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (42.9) | ||

| Educational level of father | Not educated | 4 (66.7) | 2 (33.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0.241 |

| School | 8 (34.8) | 8 (34.8) | 1 (4.3) | 6 (26.1) | ||

| High diploma | 6 (37.5) | 3 (18.8) | 3 (18.8) | 4 (25.0) | ||

| Bachelors | 40 (64.5) | 14 (22.6) | 2 (3.2) | 6 (9.7) | ||

| Master | 7 (58.3) | 2 (16.7) | 1 (8.3) | 2 (16.7) | ||

| PhD | 16 (66.7) | 5 (20.8) | 1 (4.2) | 2 (8.3) | ||

| Socioeconomic status | Upper class | 1 (50.0) | 1 (50.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0.093 |

| Upper-middle class | 33 (62.3) | 9 (17.0) | 4 (7.5) | 7 (13.2) | ||

| Lower-middle class | 5 (38.5) | 2 (15.4) | 0 (0.0) | 6 (46.2) | ||

| Middle class | 41 (56.9) | 20 (27.8) | 4 (5.6) | 7 (9.7) | ||

| Lower class | 1 (33.3) | 2 (66.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| How many hours per day do you sleep? | 6 h or less | 19 (70.4) | 2 (7.4) | 1 (3.7) | 5 (18.5) | 0.002 |

| 6–8 h | 47 (67.1) | 14 (20.0) | 3 (4.3) | 6 (8.6) | ||

| 8–10 h | 15 (44.1) | 11 (32.4) | 3 (8.8) | 5 (14.7) | ||

| More than 10 h | 0 (0.0) | 7 (58.3) | 1 (8.3) | 4 (33.3) | ||

| How often do you engage in exercise or physical activity per week? | None | 31 (48.4) | 13 (20.3) | 5 (7.8) | 15 (23.4) | 0.014 |

| 1–2 times per week | 31 (63.3) | 16 (32.7) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (4.1) | ||

| 3–4 times per week | 16 (66.7) | 4 (16.7) | 3 (12.5) | 1 (4.2) | ||

| 5 or more times per week | 3 (50.0) | 1 (16.7) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (33.3) | ||

| Is there a family history of psychiatric disease? | No | 42 (65.6) | 13 (20.3) | 5 (7.8) | 4 (6.3) | 0.042 |

| Yes | 39 (49.4) | 21 (26.6) | 3 (3.8) | 16 (20.3) | ||

| Do you smoke cigarettes? | No | 76 (58.0) | 29 (22.1) | 8 (6.1) | 18 (13.7) | 0.379 |

| Yes | 5 (41.7) | 5 (41.7) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (16.7) | ||

| Do you smoke water-pipe (Shisha)? | No | 75 (57.3) | 29 (22.1) | 8 (6.1) | 19 (14.5) | 0.756 |

| Sometimes | 4 (44.4) | 4 (44.4) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (11.1) | ||

| Yes | 2 (66.7) | 1 (33.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Parameter | Category | OR (95% CI) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| How many hours per day do you sleep? | 6 h or less | Ref. | Ref. |

| 6–8 h | 3.477 (0.717–16.874) | 0.122 | |

| 8–10 h | 7.266 (1.378–38.305) | 0.019 | |

| More than 10 h | 33.007 (4.389–248.221) | 0.001 | |

| How often do you engage in exercise or physical activity per week? | None | Ref. | Ref. |

| 1–2 times per week | 3.485 (1.250–9.715) | 0.017 | |

| 3–4 times per week | 1.596 (0.404–6.307) | 0.505 | |

| 5 or more times per week | 0.861 (0.082–9.067) | 0.901 | |

| Is there a family history of psychiatric disease? | No | Ref. | Ref. |

| Yes | 1.076 (0.451–2.567) | 0.870 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Almarghalani, D.A.; Al-Otaibi, K.M.; Labban, S.Y.; Fathelrahman, A.I.; Alzahrani, N.A.; Aljuhaiman, R.; Jamous, Y.F. Prevalence and Impact of Antidepressant and Anti-Anxiety Use Among Saudi Medical Students: A National Cross-Sectional Study. Healthcare 2025, 13, 1854. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13151854

Almarghalani DA, Al-Otaibi KM, Labban SY, Fathelrahman AI, Alzahrani NA, Aljuhaiman R, Jamous YF. Prevalence and Impact of Antidepressant and Anti-Anxiety Use Among Saudi Medical Students: A National Cross-Sectional Study. Healthcare. 2025; 13(15):1854. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13151854

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlmarghalani, Daniyah A., Kholoud M. Al-Otaibi, Samah Y. Labban, Ahmed Ibrahim Fathelrahman, Noor A. Alzahrani, Reuof Aljuhaiman, and Yahya F. Jamous. 2025. "Prevalence and Impact of Antidepressant and Anti-Anxiety Use Among Saudi Medical Students: A National Cross-Sectional Study" Healthcare 13, no. 15: 1854. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13151854

APA StyleAlmarghalani, D. A., Al-Otaibi, K. M., Labban, S. Y., Fathelrahman, A. I., Alzahrani, N. A., Aljuhaiman, R., & Jamous, Y. F. (2025). Prevalence and Impact of Antidepressant and Anti-Anxiety Use Among Saudi Medical Students: A National Cross-Sectional Study. Healthcare, 13(15), 1854. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13151854