Social Media Dimensions and Productivity Among Healthcare Workers: Evidence from a Nigerian Tertiary Hospital

Abstract

1. Introduction

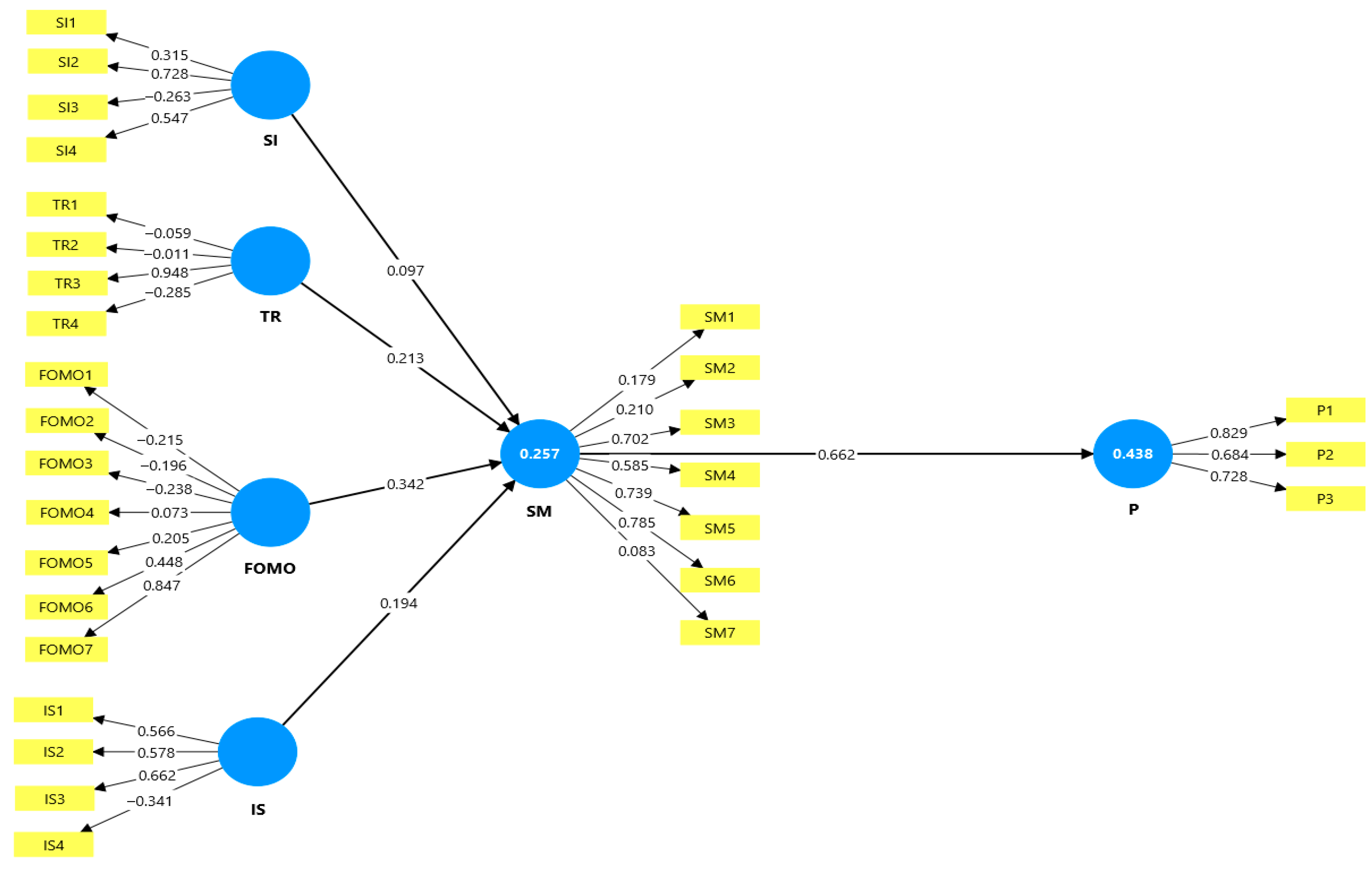

2. Theoretical Foundations and Hypothesis

2.1. Fear of Missing out on Social Media Usage

2.2. Trust of the System on Social Media Usage

2.3. Social Influence on Social Media Usage

2.4. Information Sharing on Social Media Usage

2.5. Social Media Usage on Productivity

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Measurement Scales

3.1.1. Study Design

3.1.2. Population and Sampling Technique

3.1.3. Sample Size

3.1.4. Instrument for Data Collection

3.1.5. Validation and Reliability

3.1.6. Data Analysis

3.1.7. Ethical Considerations

3.2. Common Method Bias

3.3. Structural Model Analysis

4. Result

5. Discussion

5.1. Interpretation

5.2. Theoretical Explanation

5.3. Comparative Studies

Summary of Hypothesis Test Results

5.4. Contribution

5.5. Managerial Implications

5.6. Limitations and Further Research Directions

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

Appendix A

| Construct | Items | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Social Media Usage | I often find myself using social media longer than intended. | [40] |

| I often find life to be boring without social media. | ||

| Time passes by without me feeling it when I am using social media. | ||

| My work performance has deteriorated because of my social media usage. I find myself thinking about what happened on social media when I am away from it. I feel my social media usage has increased significantly since I started using it. | ||

| Productivity | Social media helps me improve the quality of my work. | [41] |

| Social media helps me accomplish more work than would otherwise be possible. Social media helps me to perform my job better. | ||

| Information Sharing | It is acceptable if my personal health information is uploaded to social media. | [42] |

| I am not bothered if my information is shared with another health institution connected to the social media platform. | ||

| Overemphasis on patients’ privacy protection hinders the necessary flow of information sharing among health institutions on social media. | ||

| Information sharing among the units and departments is effective. | ||

| Fear of Missing Out | I fear my friends have more rewarding experiences than I do. | [40] |

| I get anxious when I don’t know what my friends are up to. | ||

| I must understand my friend’s in-jokes. | ||

| It bothers me when I miss an opportunity to meet up with friends. When I have a good time, it is important for me to share the details online (e.g., updating my status). When I miss out on a planned get-together, it bothers me. When I go on vacation, I continue to keep tabs on what my friends are doing. | ||

| Trust of the System | I trust social media to be reliable. I trust social media to be secure. I believe clinical interventions on social media are trustworthy. | [40] |

| I trust clinical decision support systems on social media. |

References

- Koessmeier, C.; Büttner, O.B. Why are we distracted by social media? Distraction situations and strategies, reasons for distraction, and individual differences. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 711416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R. Social media’s role in healthcare: Opportunities and challenges for nursing professionals. J. Healthc. Inform. 2024, 19, 98–112. [Google Scholar]

- Dailah, S.R.; Naeem, M.A. A social media organizational productivity model: Insights from public health professionals. J. Med. Internet Res. 2021, 23, e23792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coffin, J.; Ayyappan, V. Effects of social media and online reviews on healthcare. Healthc. Adm. Leadersh. Manag. J. 2023, 1, 171–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milella, F.; Minelli, E.A.; Strozzi, F.; Croce, D. Change and innovation in healthcare: Findings from literature. Clin. Econ. Outcomes Res. 2021, 13, 395–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bayrak, R. The main concepts of productivity the effects of COVID-19 on the agricultural food sector productivity. In SMEs in Agriculture and Food Industry During the Health Crises; Ozturk, L., Bayrak, R., Erhan, L., Eds.; Studies in Systems, Decision, and Control; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; Volume 576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Xiao, L.; Kumar, A. Spread of misinformation on social media: What contributes to it and how to combat it. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2023, 141, 107643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oladapo, Y.O.; Opele, J.K.; Adeoye, M.O. Social media use for medical information sharing among medical officers in Nigeria: Implication for librarianship. Libr. Philos. Pract. (e-J.) 2021, 6200, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Alzaabi, Y.S.R.; Alshehhi, S.M.A. The Negative Effects of Social Media Usage on Employee Performance—A Conceptual Analysis. Int. J. Intellect. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2023, 4, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kock, N. Common method bias in PLS-SEM: A full collinearity assessment approach. Int. J. e-Collab. 2015, 11, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis, 7th ed.; Pearson Education Inc.: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Diamantopoulos, A.; Winklhofer, H.M. Index construction with formative indicators: An alternative to scale development. J. Mark. Res. 2001, 38, 269–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, J.P. Applied Multivariate Statistics for the Social Sciences, 2nd ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Sarstedt, M.; Hair, J.F.; Cheah, J.H.; Becker, J.M.; Ringle, C.M. How to specify, estimate, and validate higher-order constructs in PLS-SEM. Australas. Mark. J. 2019, 27, 197–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. Partial Least Squares Path Modeling: Recent Advances in PLS-SEM. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2021, 29, 255–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhir, A.; Krietenstein, C.; Misra, S.; Ng, A. Determinants of social media engagement in professional settings: A systematic review. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2018, 79, 223–237. [Google Scholar]

- Naslund, J.A.; Bondre, A.; Torous, J.; Aschbrenner, K.A. Social media and mental health: Benefits, risks, and opportunities for research and practice. J. Technol. Behav. Sci. 2020, 5, 245–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. Multivariate Data Analysis: An Applied Orientation, 8th ed.; Pearson: Harlow, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. Partial Least Squares Path Modeling: Recent Advances in PLS-SEM and Applications. In Partial Least Squares Path Modeling: Basic Concepts, Methodological Issues and Applications; Henseler, J., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; pp. 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Hair, J.F. PLS-SEM: Indeed a Silver Bullet. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 153, 264–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Przybylski, A.K.; Murayama, K.; DeHaan, C.R.; Gladwell, V. Motivational, emotional, and behavioural correlates of Fear of Missing Out. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2013, 29, 1841–1848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gefen, D.; Karahanna, E.; Straub, D.W. Trust and TAM in online shopping: An integrated model. MIS Q. 2003, 27, 51–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, A.M.; Haenlein, M. Users of the world, unite! The challenges and opportunities of social media. Bus. Horiz. 2010, 53, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, C. A comprehensive first-year engagement theory. J. Access Retent. Incl. High. Educ. 2021, 1, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Venkatesh, V.; Morris, M.G.; Davis, G.B.; Davis, F.D. User acceptance of information technology: Toward a unified view. MIS Q. 2003, 27, 425–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sickles, R.C.; Zelenyuk, V. Measurement of Productivity and Efficiency: Theory and Practice; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Xiong, F.; Xie, Y.; Fan, X.; Gu, H. The Impact of Artificial Intelligence and Blockchain on the Accounting Profession. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 110461–110477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fayoyin, A. Engaging social media for health communication in Africa: Approaches, results and lessons. J. Mass Commun. J. 2016, 6, 315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shittu, R.O.; Falade, P.A.; Akinola, S.O.; Olagunju, A. Knowledge gap of primary health care system in Nigeria: A conceptual difference. Niger. J. Rural. Sociol. 2023, 23, 38–44. [Google Scholar]

- Masefield, S.C.; Msosa, A.; Chinguwo, F.K.; Grugel, J. Stakeholder engagement in the health policy process in a low-income country: A qualitative study of stakeholder perceptions of the challenges to effective inclusion in Malawi. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2021, 21, 984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshanqiti, A.; Alharbi, O.A.; Ismaeel, D.M.; Abuanq, L. Social Media Usage and Academic Performance Among Medical Students in Medina, Saudi Arabia. Adv. Med. Educ. Pract. 2023, 14, 1401–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeyaraman, M.; Ramasubramanian, S.; Kumar, S.; Jeyaraman, N.; Selvaraj, P.; Nallakumarasamy, A.; Bondili, S.K.; Yadav, S. The multifaceted role of social media in healthcare: Opportunities, challenges, and the need for quality control. Cureus 2023, 15, e39111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benetoli, A.; Chen, T.F.; Aslani, P. How patients’ use of social media impacts their interactions with healthcare professionals. Patient Educ. Couns. 2018, 101, 439–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruce, E.; Shurong, Z.; Amoah, J.; Egala, S.B.; Sobre Frimpong, F.K. Reassessing the impact of social media on healthcare delivery: Insights from a less digitalized economy. Cogent Public Health 2024, 11, 2301127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghahramani, A.; de Courten, M.; Prokofieva, M. The potential of social media in health promotion beyond creating awareness: An integrative review. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 2402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruzd, A.; Soares, F.B.; Mai, P. Trust and safety on social media: Understanding the impact of anti-social behavior and misinformation on content moderation and platform governance. Soc. Media Soc. 2023, 9, 20563051231196878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzuti, J.C. Social media: Are the lines between professional and personal use blurring? McMaster J. Commun. 2020, 12, 78–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarafdar, M.; Cooper, C.L.; Stich, J.-F. The technostress trifecta—Techno eustress, techno distress, and design: Theoretical directions and an agenda for research. Inform. Syst. J. 2019, 29, 6–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, S.; Califf, C. Social media-induced technostress: Its impact on the job performance of IT professionals and the moderating role of job characteristics. Comput. Netw. 2017, 114, 143–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinecke, L.; Vorderer, P.; Knop, K. Entertainment 2.0? The role of intrinsic and extrinsic needs satisfaction for the enjoyment of Facebook use. J. Commun. 2014, 64, 417–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oksa, R.; Pirkkalainen, H.; Salo, M.; Savela, N.; Oksanen, A. Professional social media-enabled productivity: A five-wave longitudinal study on the role of professional social media invasion, work engagement, and work exhaustion. Inf. Technol. People 2022, 35, 349–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idoga, P.E.; Bakre, M.T.; Nadiri, H.; Celebi, E. Assessing factors militating against the acceptance and successful implementation of a cloud-based health center from the healthcare professionals’ perspective: A survey of hospitals in Benue state, north-central Nigeria. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2019, 19, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Construct | Factor Loading | Cronbach’s Alpha (α) | Composite Reliability | Average Variance Extracted (AVE) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SI | 0.248 | 0.614 | 0.288 | 0.611 |

| 0.361 | ||||

| 0.266 | ||||

| T | 0.546 | 0.592 | 0.556 | 0.674 |

| 0.421 | ||||

| 0.422 | ||||

| 0.559 | ||||

| FoMO | 0.742 | 0.584 | 0.826 | 0.641 |

| 0.820 | ||||

| 0.649 | ||||

| 0.450 | ||||

| 0.656 | ||||

| 0.625 | ||||

| IS | 0.500 | 0.520 | 0.734 | 0.683 |

| 0.554 | ||||

| 0.688 | ||||

| SMU | 0.661 | 0.572 | 0.854 | 0.616 |

| 0.623 | ||||

| 0.661 | ||||

| 0.688 | ||||

| 0.797 | ||||

| 0.661 | ||||

| PI | 0.596 | 0.622 | 0.693 | 0.645 |

| 0.625 | ||||

| 0.742 | ||||

| 0.716 |

| FOMO | IS | P | SI | SMU | T | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FOMO | 0.813 | |||||

| IS | 0.786 | 0.864 | ||||

| P | 0.680 | 0.703 | 0.825 | |||

| SI | 0.700 | 0.609 | 0.596 | 0.872 | ||

| SMU | 0.762 | 0.826 | 0.814 | 0.614 | 0.790 | |

| T | 0.803 | 0.651 | 0.616 | 0.814 | 0.666 | 0.833 |

| Direct Effects | Beta | SE | t-Values | p-Values | Hypothesis | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | (FOMO) → (SMU) | 0.430 | 0.075 | 0.733 | 0.001 | Accepted |

| H2 | (T) → (SMU) | 0.416 | 0.095 | 0.303 | 0.003 | Accepted |

| H3 | (SI) → (SMU) | 0.430 | 0.075 | 0.733 | 0.001 | Accepted |

| H4 | (IS) → (SMU) | 0.579 | 0.115 | 3.359 | 0.000 | Accepted |

| H5 | (SMU) → (P) | 0.577 | 0.246 | 13.065 | 0.000 | Accepted |

| Paths | β Coefficient | p-Values | f2 (Effect Sizes) | Result | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | (FOMO) → (SMU) | 0.430 | 0.001 | 0.097 | supported |

| H2 | (T) → (SMU) | 0.416 | 0.003 | 0.055 | supported |

| H3 | (SI) → (SMU) | 0.430 | 0.001 | 0.766 | supported |

| H4 | (IS) → (SMU) | 0.579 | 0.000 | 0.010 | supported |

| H5 | (SMU) → (P) | 0.577 | 0.000 | 0.061 | supported |

| Endogenous Construct | R2 | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Social Media Usage | 0.663 | 0.001 |

| Productivity | 0.723 | 0.003 |

| Endogenous Construct | Q2 | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Social Media Usage | 0.024 | 0.001 |

| Productivity | 0.129 | 0.003 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Uzoeghelu, P.C.; Agoyi, M. Social Media Dimensions and Productivity Among Healthcare Workers: Evidence from a Nigerian Tertiary Hospital. Healthcare 2025, 13, 1836. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13151836

Uzoeghelu PC, Agoyi M. Social Media Dimensions and Productivity Among Healthcare Workers: Evidence from a Nigerian Tertiary Hospital. Healthcare. 2025; 13(15):1836. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13151836

Chicago/Turabian StyleUzoeghelu, Precious Chisom, and Mary Agoyi. 2025. "Social Media Dimensions and Productivity Among Healthcare Workers: Evidence from a Nigerian Tertiary Hospital" Healthcare 13, no. 15: 1836. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13151836

APA StyleUzoeghelu, P. C., & Agoyi, M. (2025). Social Media Dimensions and Productivity Among Healthcare Workers: Evidence from a Nigerian Tertiary Hospital. Healthcare, 13(15), 1836. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13151836