Balloon Eustachian Tuboplasty: A Systematic Review of Technique, Safety, and Clinical Outcomes in Chronic Obstructive Eustachian Tube Dysfunction

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Conservative management:

- Autoinflation and maneuvers (e.g., Valsalva, Toynbee): help equalize middle-ear pressure.

- Nasal therapies (steroids, decongestants, antihistamines): may reduce inflammation, but intranasal steroids show limited benefit (11–18%) in chronic ETD—by Llewellyn et al.

- Saline irrigation and adjuncts (swallowing exercises, smoking cessation, allergy control): supportive with modest benefits.

- Medical treatment:

- Oral steroids or antibiotics: reserved for infection/inflammation; inconsistent evidence for long-term superiority.

- Procedural/surgical interventions:

- Myringotomy with tympanostomy tubes provides temporary relief but does not correct ET dysfunction.

- Emerging techniques (laser/microwave tuboplasty, transtubal tools): promising but require further validation.

- Balloon Eustachian tuboplasty (BDET/BET).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Literature Retrieval

2.2. Data Extraction

2.3. PICO

- -

- Population: adult patients with OEDT and/or otitis media

- -

- Intervention: BDET (using a balloon of any size or pressure, conducted under both general and local anesthesia) as a sole procedure or in combination with other treatments (involving nose, paranasal sinuses, and ear)

- -

- Comparison:

- *

- Comparison with no treatment

- *

- Comparison with pharmacological treatments

- *

- Comparison with other methods of surgical treatment

- *

- Comparison of different techniques of performing the procedurę or the results obtained with the use of local and general anesthesia

- -

- Outcomes (results analyzed at the different time points used in each study—without exclusions):

- (1)

- Primary outcomes:

- *

- Patient-reported symptom severity and quality of life assessment (using the questionnaires used by the researchers)

- *

- Results of tonal and impedance audiometry examination

- *

- Evaluation of adverse events

- (2)

- Secondary outcomes:

- *

- Otoscopic findings

- *

- Evaluation of auditory trumpet function using the Valsalva or Toynbee manoeuvre

- *

- Others were assessed in individual studies, e.g., cost assessment, the graft success rate (in the case of simultaneous myringoplasty), or endoscopic evaluation.

3. Results

3.1. Search Results

3.2. Study Characteristics

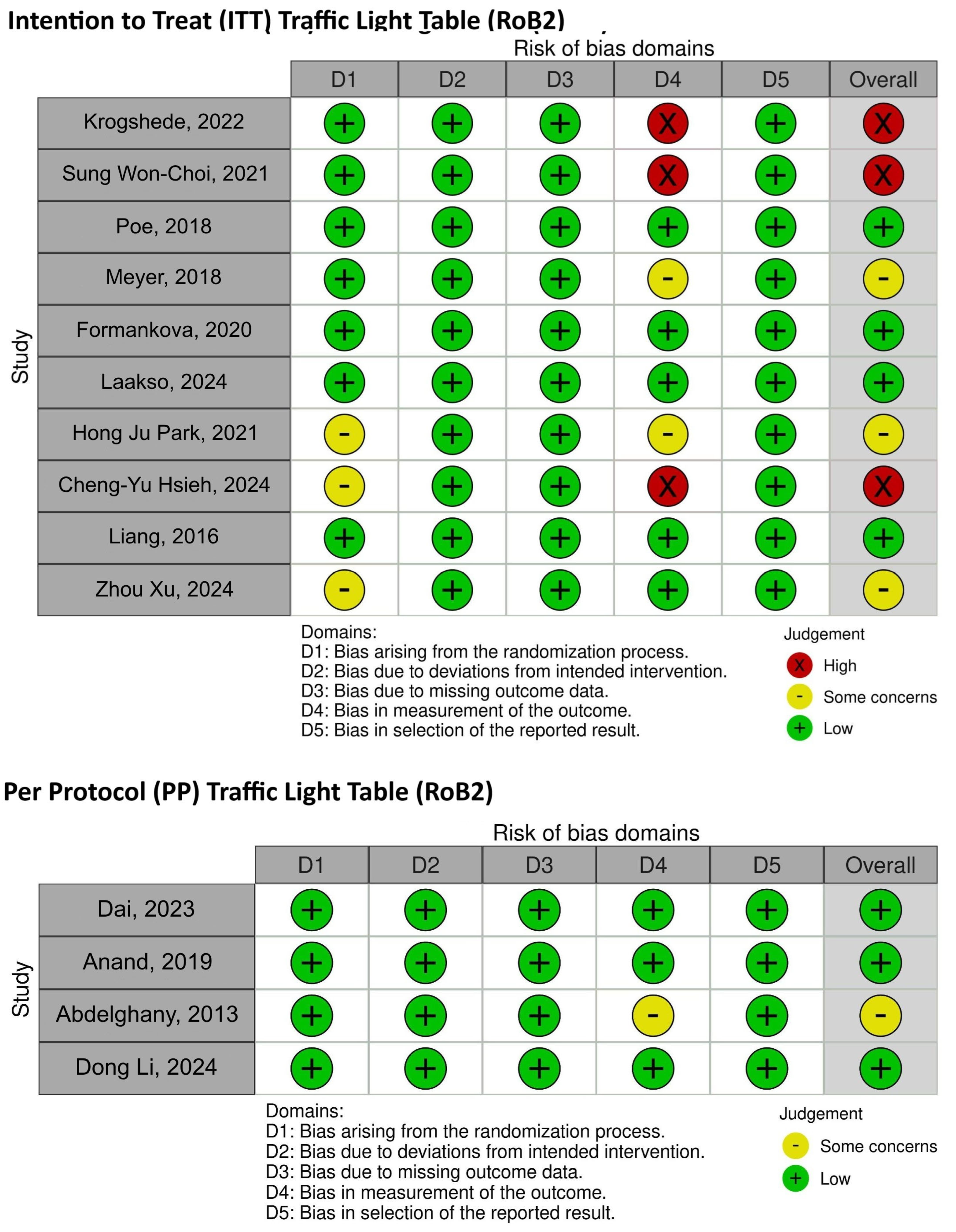

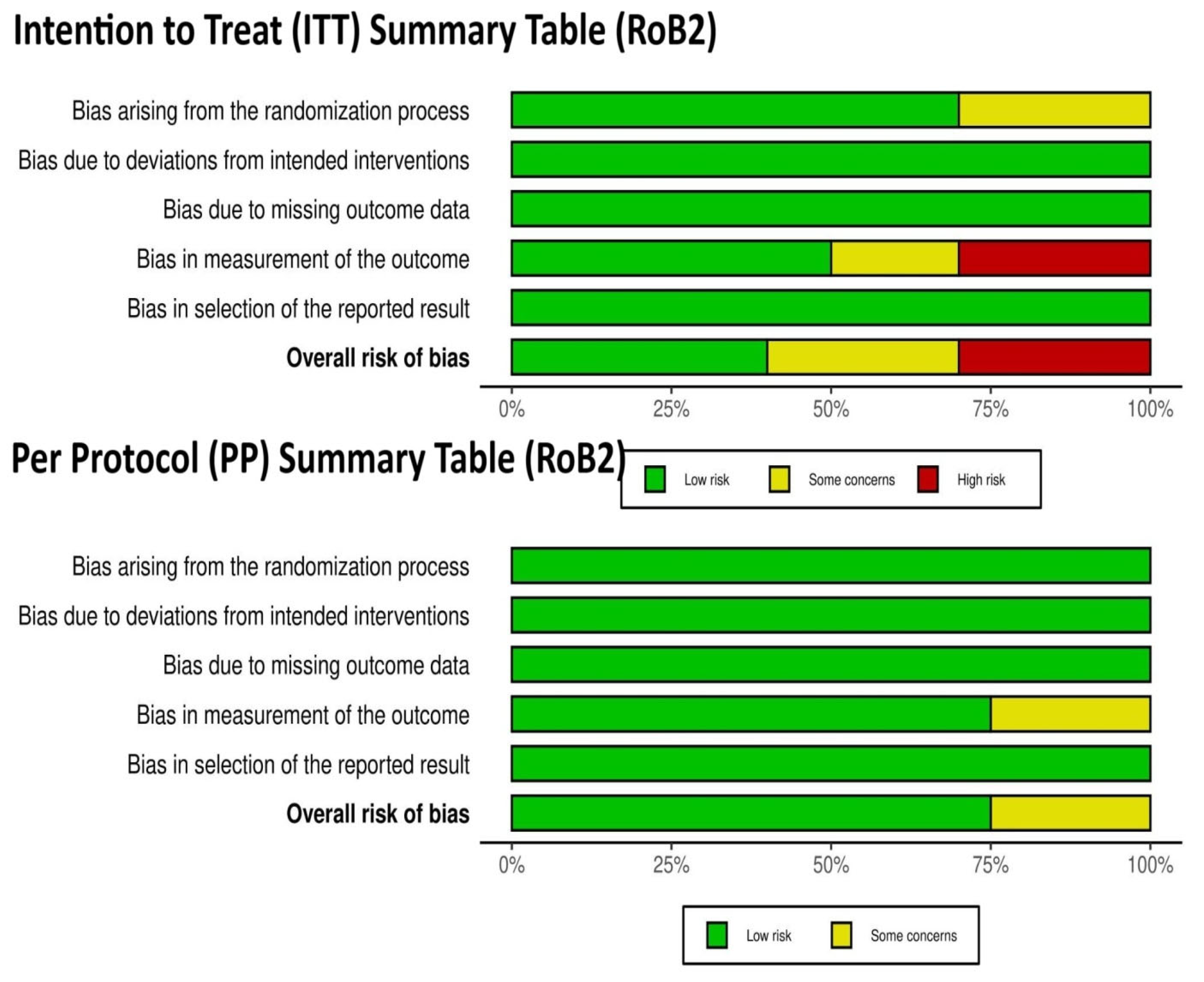

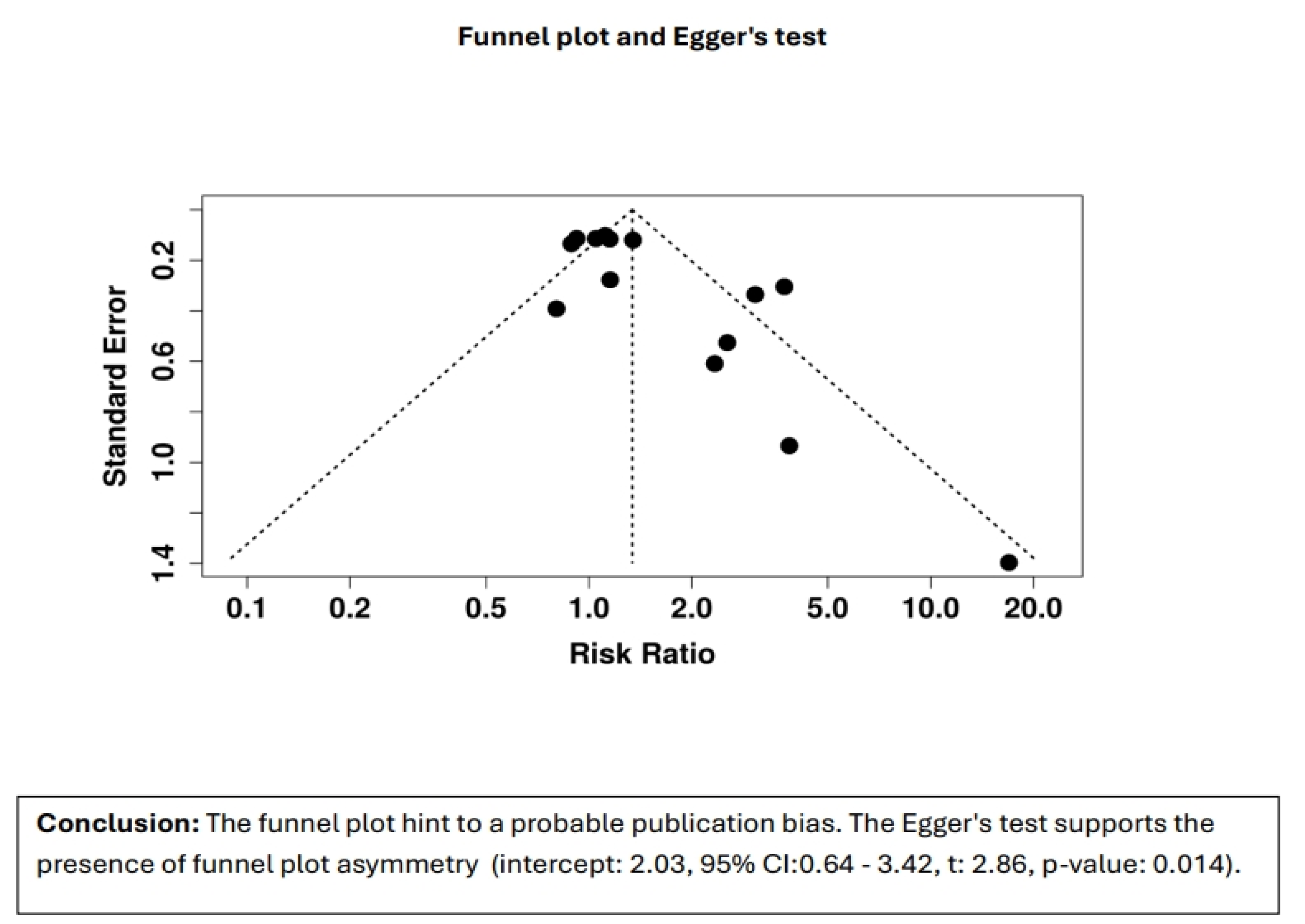

3.3. Risk-of-Bias Assessment

3.4. Effectiveness of BDET

3.4.1. Otoscopic and Valsalva Maneuver Results of BDET

3.4.2. The Pure Tone Audiometry and Tympanometry Results of BDET

3.4.3. The ETDQ-7 Results of BDET

3.5. Safety and the Main Exclusion Criteria for the BDET Technique

- Active infection: acute otitis media or any active infection in the middle ear or sinus (all papers).

- Allergic rhinitis or uncontrolled sinusitis [22].

- Severe nasopharyngeal pathology: structural abnormalities or tumors in the nasopharynx (most papers).

- Cleft lip and palate (most paper).

- Patulous ET: a condition where ET stays open too much, which BDET cannot treat effectively (all papers).

- Preoperative air-bone gap (ABG) above 30 dB 20.

- Fungal otitis externa [20].

- Major head or neck surgery (most papers).

- Prior head and neck radiation: radiotherapy affecting healing and procedure outcomes (most papers).

- Smoking [19].

3.6. Kind of Anesthesia During BDET Procedure

3.7. BDET Technique

3.8. BDET as Additional Procedure

4. Discussion

- Included seven studies involving 408 children, mean age 9.9 years, with average follow-up of ~19 months. Type B tympanograms decreased from 64.2% to 16.1%.

- Air-bone gap (ABG) improved from 25.3 dB to 10.2 dB.

- Adverse events occurred in ~5.1%, mostly self-limited epistaxis.

- In three studies comparing ventilation tubes, BDET showed superior ABG reduction (mean difference −6.4 dB, p = 0.002)

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ABG | air-bone gap |

| BDET | balloon dilation of the Eustachian tube |

| CG | control group |

| CNM | cartilage underlay myringoplasty |

| COME | chronic otitis media with effusion |

| CRS | chronic rhinosinusitis |

| ESS | endoscopic sinus surgery |

| ET | Eustachian tube |

| ETS | Eustachian tube score |

| ETD | Eustachian tube dysfunction |

| ETDQ-7 | Eustachian Tube Dysfunction Questionnaire-7 |

| EVB | endovascular balloon |

| GA | general anesthesia |

| LA | local anesthesia |

| MM | medical management |

| OETD | obstructive Eustachian tube dysfunction |

| OMS | otitis media secretory |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| PTA | pure tone audiometry |

| RCT | randomized controlled trial |

| SNOT-22 | sinonasal outcome test 22 |

| TBI | tympanotomy tube insertion |

| TM | tympanic membrane |

| TMM | tympanometry |

| VAS | visual analog scale |

| VM | Valsalva maneuver |

References

- Schilder, A.G.; Bhutta, M.F.; Butler, C.C.; Holy, C.; Levine, L.H.; Kvaerner, K.J.; Norman, G.; Pennings, R.J.; Poe, D.; Silvola, J.T.; et al. Eustachian tube dysfunction: Consensus statement on definition, types, clinical presentation and diagnosis. Clin. Otolaryngol. 2015, 40, 407–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browning, G.G.; Gatehouse, S. The prevalence of middle ear disease in the adult British population. Clin. Otolaryngol. Allied Sci. 1992, 17, 317–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semaan, M.T.; Megerian, C.A. The pathophysiology of cholesteatoma. Otolaryngol. Clin. N. Am. 2006, 39, 1143–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olszewska, E.; Wagner, M.; Bernal-Sprekelsen, M.; Ebmeyer, J.; Dazert, S.; Hildmann, H.; Sudhoff, H. Etiopathogenesis of cholesteatoma. Eur. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 2004, 261, 6–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCoul, E.D.; Anand, V.K.; Christos, P.J. Validating the clinical assessment of eustachian tube dysfunction: The Eustachian Tube Dysfunction Questionnaire (ETDQ-7). Laryngoscope 2012, 122, 1137–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ockermann, T.; Reineke, U.; Upile, T.; Ebmeyer, J.; Sudhoff, H.H. Balloon dilatation eustachian tuboplasty: A clinical study. Laryngoscope 2010, 120, 1411–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kivekäs, I.; Chao, W.; Faquin, W.; Hollowell, M.; Silvola, J.; Rasooly, T.; Poe, D. Histopathology of balloon-dilation Eustachian tuboplasty. Laryngoscope 2015, 125, 436–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tisch, M.; Maier, H.; Sudhoff, H. Balloon dilation of the Eustachian tube: Clinical experience in the management of 126 children. Acta Otorhinolaryngol. Ital. 2017, 37, 509–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swords, C.; Smith, M.E.; Patel, A.; Norman, G.; Llewellyn, A.; Tysome, J.R. Balloon dilatation of the Eustachian tube for obstructive Eustachian tube dysfunction in adults. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2025, 2, Cd013429. [Google Scholar]

- Page, M.J.; Moher, D.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, R.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. PRISMA 2020 explanation and elaboration: Updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelghany, A.M. Does balloon Eustachian tuboplasty increase the success rate in repair of subtotal tympanic membrane perforations with resistant tubal dysfunction? Egypt. J. Ear Nose Throat Allied Sci. 2013, 14, 97–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anand, V.; Poe, D.; Dean, M.; Roberts, W.; Stolovitzky, P.; Hoffmann, K.; Nachlas, N.; Light, J.; Widick, M.; Sugrue, J.; et al. Balloon Dilation of the Eustachian Tube: 12-Month Follow-up of the Randomized Controlled Trial Treatment Group. Otolaryngol. Head. Neck Surg. 2019, 160, 687–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.-W.; Oh, S.-J.; Kim, Y.; Kwak, M.Y.; Suh, M.-W.; Park, M.K.; Lee, C.K.; Park, H.J.; Kong, S.-K. A multicenter, randomized, active-controlled, clinical trial study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of navigation guided balloon Eustachian tuboplasty. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 23296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, B.; Yin, X.; Guo, D.; Du, X. Balloon Dilation Eustachian Tuboplasty Combined with Tympanotomy Tube Insertion for Treatment of Refractory Otitis Media with Effusion: A Randomized, Prospective, Controlled Trial Comparing Local Anesthesia Combined Sedation Versus General Anesthesia. Med. Sci. Monit. 2023, 29, e938879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Formánková, D.; Formánek, M.; Školoudík, L.; Zeleník, K.; Tomášková, H.; Chrobok, V.; Komínek, P. Balloon Eustachian Tuboplasty Combined with Tympanocentesis Is not Superior to Balloon Eustachian Tuboplasty in Chronic Otitis Media with Effusion-A Randomized Clinical Trial. Otol. Neurotol. 2020, 41, 339–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, C.Y.; Lin, W.C.; Lin, C.C.; Chou, Y.F. Combined balloon Eustachian tuboplasty/endoscopic sinus surgery for patients with chronic rhinosinusitis and Eustachian tube dysfunction. Int. Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2024, 14, 1327–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, H.J. A Prospective Multicenter Randomized Controlled Study for the Evaluation of Efficacy and Safety of Balloon Eustachian Tuboplasty for Patients with Chronic Otitis Media Due to Obstructive Tube Dysfunction. Available online: https://trialsearch.who.int/Trial2.aspx?TrialID=KCT0005817 (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- Kjær Krogshede, S.; Kirchmann, M.; Peter Schjellerup Jørkov, A.; Glad, H. Balloon Dilation of the Eustachian Tube: A Randomized Controlled Trial with 6 Months Follow-Up. J. Int. Adv. Otol. 2022, 18, 501–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laakso, J.T.; Oehlandt, H.; Kivekäs, I.; Harju, T.; Jero, J.; Sinkkonen, S.T. Balloon Eustachian Tuboplasty-A Feasible Double-Blinded Sham Surgery Randomized Clinical Trial Protocol to Study Efficacy. Laryngoscope 2024, 134, 1874–1881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Wei, R.; Ding, Y.; Hu, R.; Chen, S.; Liu, C.; Xin, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, Y. Endoscopic cartilage underlay myringoplasty with or without balloon Eustachian tuboplasty for chronic perforation with Eustachian tube dysfunction. Am. J. Otolaryngol. 2024, 45, 104475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, M.; Xiong, H.; Cai, Y.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, S.; Xu, Y.; Ou, Y.; Yang, H.; Zheng, Y. Effect of the combination of balloon Eustachian tuboplasty and tympanic paracentesis on intractable chronic otitis media with effusion. Am. J. Otolaryngol. 2016, 37, 442–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyer, T.A.; O’mAlley, E.M.; Schlosser, R.J.; Soler, Z.M.; Cai, J.; Hoy, M.J.; Slater, P.W.; Cutler, J.L.; Simpson, R.J.; Clark, M.J.; et al. A Randomized Controlled Trial of Balloon Dilation as a Treatment for Persistent Eustachian Tube Dysfunction with 1-Year Follow-Up. Otol. Neurotol. 2018, 39, 894–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poe, D.; Anand, V.; Dean, M.; Roberts, W.H.; Stolovitzky, J.P.; Hoffmann, K.; Nachlas, N.E.; Light, J.P.; Widick, M.H.; Sugrue, J.P.; et al. Balloon dilation of the eustachian tube for dilatory dysfunction: A randomized controlled trial. Laryngoscope 2018, 128, 1200–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, P.; Cao, X.; Zhang, R.; Liu, Y.; Li, H.; Wang, W.; Li, W. The long-term efficacy and safety of balloon dilation eustachian tuboplasty combined with tympanostomy tube insertion for patients with otitis media with effusion: Study protocol for a prospective randomized controlled trial. Trials 2024, 25, 572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Yan, X. Balloon dilation of Eustachian tube combined with triamcinolone acetonide therapy for secretory otitis media. Trop. J. Pharm. Res. 2024, 23, 1917–1923. [Google Scholar]

- Hussain, S.Z.M.; Hashmi, S.; Qayyum, A. Informed consent in balloon Eustachian tuboplasty: A systematic review of possible complications and preventive measures. J. Laryngol. Otol. 2024, 138, 474–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skevas, T.; Dalchow, C.V.; Euteneuer, S.; Sudhoff, H.; Lehnerdt, G. Cervicofacial and mediastinal emphysema after balloon eustachian tuboplasty (BET): A retrospective multicenter analysis. Eur. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 2018, 275, 81–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Sun, N.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, H.; Cai, X.; Li, X. Inflammatory infiltration and tissue remodeling in nasal polyps and adjacent mucosa of unaffected sinus. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 2018, 11, 2707–2713. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ungar, O.J.; Demir Bajin, M.; Dahm, V.; Lin, V.Y.W.; Chen, J.M.; Le, T.N. Balloon dilation of the eustachian tube using endovascular balloon under local anesthesia-a case series and systematic literature review. Front. Surg. 2024, 11, 1271248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dahm, V.; Lui, J.T.; Jung, S.; Lin, V.Y.; Chen, J.M.; Le, T.N. The feasibility and safety of eustachian tube dilation with a standard endovascular balloon: A clinical pilot study. J. Otolaryngol. Head. Neck Surg. 2023, 52, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miljkovic, D.; Psaltis, A.; Wormald, P.J.; Vreugde, S. T regulatory and Th17 cells in chronic rhinosinusitis with polyps. Int. Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2016, 6, 826–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Database | Number of Results | Search Strategy |

|---|---|---|

| Pubmed | 209 | ((„Eustachian tube” OR „pharyngotympanic tube” OR „auditory tube”) AND („dysfunction” OR „obstruction” OR „obstructive”)) OR “Otitis Media with Effusion” [Mesh]) AND („balloon” AND („dilation” OR „tuboplasty”)) |

| Scopus | 215 | TITLE-ABS-KEY ((((((eustachian AND tube) OR (pharyngotympanic AND tube) OR (auditory AND tube)) AND ((dysfunction) OR (obstruction) OR (obstructive))) OR (otitis)) AND ((balloon) AND ((dilation) OR (tuboplasty))))) AND (LIMIT-TO (LANGUAGE, “English”)) |

| Cochrane | 46 | #1 eustachian tube OR pharyngotympanic tube OR auditory tube #2 dysfunction OR obstruction OR obstructive #3 otitis #4 balloon #5 dilation OR tuboplasty #6 ((#1 AND #2) OR #3) AND (#4 AND #5) And Trials |

| Web of Science | 243 | TS =(((((eustachian AND tube) OR (pharyngotympanic AND tube) OR (auditory AND tube)) AND ((dysfunction) OR (obstruction) OR (obstructive))) OR (otitis)) AND ((balloon) AND ((dilation) OR (tuboplasty)))) |

| Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|

| Original articles presenting the results of balloon dilation of the eustachian tube (including case series in people who have previously been treated medically or surgically) | Conference papers and abstracts, reviews, editorials, case reports, retrospective studies, opinions, or letters |

| Randomized controlled trials (by patient and by ear) | Studies involving patients with nasopharyngeal malignancy and radiation therapy of the head and neck |

| Human study | Animal study |

| Study on adults | Study on children |

| Full-text articles available in English | Language other than English, only abstracts available |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gołota, K.; Czerwaty, K.; Dżaman, K.; Szczepański, D.; Ludwig, N.; Szczepański, M.J. Balloon Eustachian Tuboplasty: A Systematic Review of Technique, Safety, and Clinical Outcomes in Chronic Obstructive Eustachian Tube Dysfunction. Healthcare 2025, 13, 1832. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13151832

Gołota K, Czerwaty K, Dżaman K, Szczepański D, Ludwig N, Szczepański MJ. Balloon Eustachian Tuboplasty: A Systematic Review of Technique, Safety, and Clinical Outcomes in Chronic Obstructive Eustachian Tube Dysfunction. Healthcare. 2025; 13(15):1832. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13151832

Chicago/Turabian StyleGołota, Katarzyna, Katarzyna Czerwaty, Karolina Dżaman, Dawid Szczepański, Nils Ludwig, and Mirosław J. Szczepański. 2025. "Balloon Eustachian Tuboplasty: A Systematic Review of Technique, Safety, and Clinical Outcomes in Chronic Obstructive Eustachian Tube Dysfunction" Healthcare 13, no. 15: 1832. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13151832

APA StyleGołota, K., Czerwaty, K., Dżaman, K., Szczepański, D., Ludwig, N., & Szczepański, M. J. (2025). Balloon Eustachian Tuboplasty: A Systematic Review of Technique, Safety, and Clinical Outcomes in Chronic Obstructive Eustachian Tube Dysfunction. Healthcare, 13(15), 1832. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13151832