Effectiveness of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) in Patient with Cardiovascular Disease: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Epidemiological Burden in Italy

1.2. Stress as a Cardiovascular Risk Factor

1.3. The Interplay Between Depression and CVDs

2. Materials and Methods

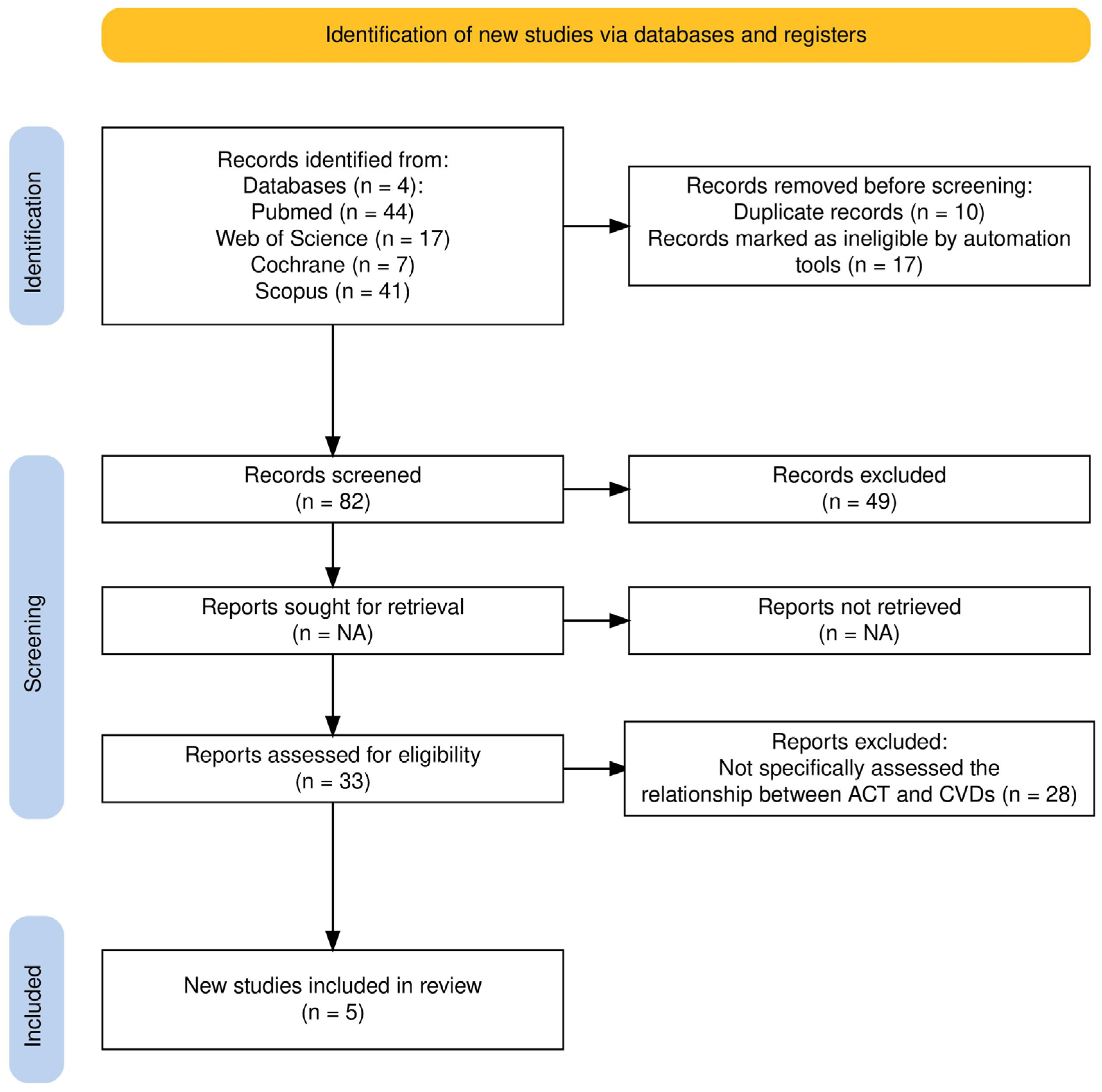

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Study Selection

2.3. Data Extraction and Analysis

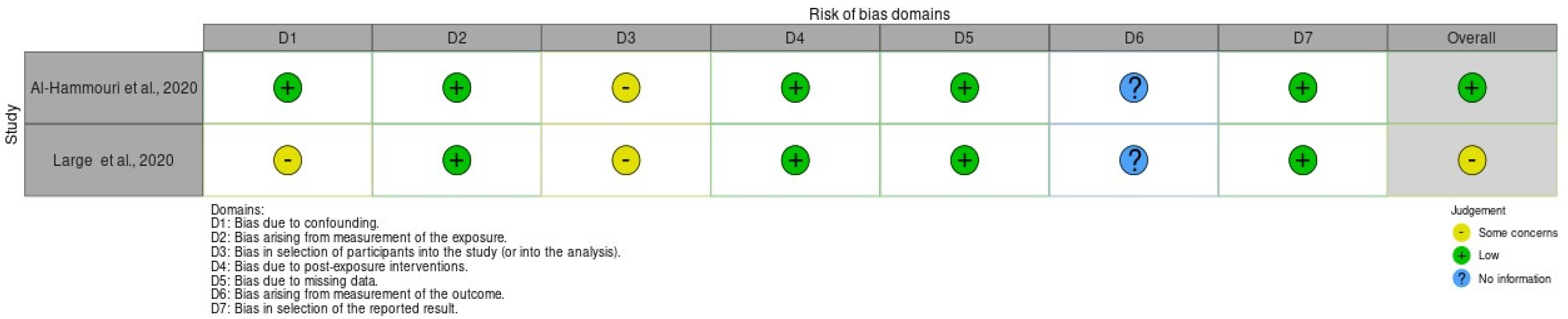

2.4. Assess Quality of Included Studies’ Risk of Bias

3. Results

3.1. Synthesis of Evidence

3.2. Key Findings from Included Studies

3.3. Risk of Bias

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations

4.2. Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Olvera Lopez, E.; Ballard, B.D.; Jan, A. Cardiovascular Disease; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Correll, C.U.; Solmi, M.; Veronese, N.; Bortolato, B.; Rosson, S.; Santonastaso, P.; Thapa-Chhetri, N.; Fornaro, M.; Gallicchio, D.; Collantoni, E.; et al. Prevalence, Incidence and Mortality from Cardiovascular Disease in Patients with Pooled and Specific Severe Mental Illness: A Large-scale Meta-analysis of 3,211,768 Patients and 113,383,368 Controls. World Psychiatry 2017, 16, 163–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kassebaum, N.J.; Arora, M.; Barber, R.M.; Bhutta, Z.A.; Brown, J.; Carter, A.; Casey, D.C.; Charlson, F.J.; Coates, M.M.; Coggeshall, M.; et al. Global, Regional, and National Disability-Adjusted Life-Years (DALYs) for 315 Diseases and Injuries and Healthy Life Expectancy (HALE), 1990–2015: A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet 2016, 388, 1603–1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roth, G.A.; Abate, D.; Abate, K.H.; Abay, S.M.; Abbafati, C.; Abbasi, N.; Abbastabar, H.; Abd-Allah, F.; Abdela, J.; Abdelalim, A.; et al. Global, Regional, and National Age-Sex-Specific Mortality for 282 Causes of Death in 195 Countries and Territories, 1980–2017: A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet 2018, 392, 1736–1788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, X.; Zheng, Y.; Ma, J.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, X.; Chen, L.; Yang, Q.; Sun, Y.; Wu, J.; et al. Effect of Exercise-Based Cardiac Rehabilitation on Anxiety and Depression in Patients with Myocardial Infarction: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Heart Lung 2019, 48, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davidson, K.W.; Alcántara, C.; Miller, G.E. Selected Psychological Comorbidities in Coronary Heart Disease: Challenges and Grand Opportunities. Am. Psychol. 2018, 73, 1019–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Field, T. Tai Chi Research Review. Complement. Ther. Clin. Pract. 2011, 17, 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denollet, J.; Schiffer, A.A.; Spek, V. A General Propensity to Psychological Distress Affects Cardiovascular Outcomes. Circ. Cardiovasc. Qual. Outcomes 2010, 3, 546–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sin, N.L. The Protective Role of Positive Well-Being in Cardiovascular Disease: Review of Current Evidence, Mechanisms, and Clinical Implications. Curr. Cardiol. Rep. 2016, 18, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krakow, B.; Melendrez, D.; Warner, T.D.; Dorin, R.; Harper, R.; Hollifield, M. To Breathe, Perchance to Sleep: Sleep-Disordered Breathing and Chronic Insomnia Among Trauma Survivors. Sleep. Breath. 2002, 6, 189–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lett, H.S. Depression as a Risk Factor for Coronary Artery Disease: Evidence, Mechanisms, and Treatment. Psychosom. Med. 2004, 66, 305–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldston, K.; Baillie, A. Depression and Coronary Heart Disease: A Review of the Epidemiological Evidence, Explanatory Mechanisms and Management Approaches. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2008, 28, 288–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghodeshwar, G.K.; Dube, A.; Khobragade, D. Impact of Lifestyle Modifications on Cardiovascular Health: A Narrative Review. Cureus 2023, 15, e42616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ambrosetti, M.; Abreu, A.; Corrà, U.; Davos, C.H.; Hansen, D.; Frederix, I.; Iliou, M.C.; Pedretti, R.F.E.; Schmid, J.-P.; Vigorito, C.; et al. Secondary Prevention through Comprehensive Cardiovascular Rehabilitation: From Knowledge to Implementation. 2020 Update. A Position Paper from the Secondary Prevention and Rehabilitation Section of the European Association of Preventive Cardiology. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2021, 28, 460–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ismail, K.; Bayley, A.; Twist, K.; Stewart, K.; Ridge, K.; Britneff, E.; Greenough, A.; Ashworth, M.; Rundle, J.; Cook, D.G.; et al. Reducing Weight and Increasing Physical Activity in People at High Risk of Cardiovascular Disease: A Randomised Controlled Trial Comparing the Effectiveness of Enhanced Motivational Interviewing Intervention with Usual Care. Heart 2020, 106, 447–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muscogiuri, G.; Verde, L.; Sulu, C.; Katsiki, N.; Hassapidou, M.; Frias-Toral, E.; Cucalón, G.; Pazderska, A.; Yumuk, V.D.; Colao, A.; et al. Mediterranean Diet and Obesity-Related Disorders: What Is the Evidence? Curr. Obes. Rep. 2022, 11, 287–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glassman, A.H.; Shapiro, P.A. Depression and the Course of Coronary Artery Disease. Am. J. Psychiatry 1998, 155, 4–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, L.; Li, Y. The Effect of Depression on Sleep Quality and the Circadian Rhythm of Ambulatory Blood Pressure in Older Patients with Hypertension. J. Clin. Neurosci. 2017, 39, 49–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doorley, J.D.; Goodman, F.R.; Kelso, K.C.; Kashdan, T.B. Psychological Flexibility: What We Know, What We Do Not Know, and What We Think We Know. Soc. Pers. Psychol. Compass 2020, 14, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bond, F.W.; Hayes, S.C.; Barnes-Holmes, D. Psychological Flexibility, ACT, and Organizational Behavior. J. Organ. Behav. Manag. 2006, 26, 25–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmann, S.G.; Asnaani, A.; Vonk, I.J.J.; Sawyer, A.T.; Fang, A. The Efficacy of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy: A Review of Meta-Analyses. Cogn. Ther. Res. 2012, 36, 427–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayes, S.C.; Luoma, J.B.; Bond, F.W.; Masuda, A.; Lillis, J. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy: Model, Processes and Outcomes. Behav. Res. Ther. 2006, 44, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lillis, J.; Hayes, S.C.; Bunting, K.; Masuda, A. Teaching Acceptance and Mindfulness to Improve the Lives of the Obese: A Preliminary Test of a Theoretical Model. Ann. Behav. Med. 2009, 37, 58–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kashdan, T.B.; Rottenberg, J. Psychological Flexibility as a Fundamental Aspect of Health. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2010, 30, 865–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaudiano, B.A.; Herbert, J.D. Acute Treatment of Inpatients with Psychotic Symptoms Using Acceptance and Commitment Therapy: Pilot Results. Behav. Res. Ther. 2006, 44, 415–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnold, T.; Haubrick, K.K.; Klasko-Foster, L.B.; Rogers, B.G.; Barnett, A.; Ramirez- Sanchez, N.A.; Bertone, Z.; Gaudiano, B.A. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy Informed Behavioral Health Interventions Delivered by Non-Mental Health Professionals: A Systematic Review. J. Context. Behav. Sci. 2022, 24, 185–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walser, R.D.; O’Connell, M. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy and the Therapeutic Relationship: Rupture and Repair. J. Clin. Psychol. 2021, 77, 429–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, N.; Shawyer, F.; Castle, D.J.; Copolov, D.; Hayes, S.C.; Farhall, J. A Randomised Controlled Trial of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) for Psychosis: Study Protocol. BMC Psychiatry 2014, 14, 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swain, J.; Hancock, K.; Hainsworth, C.; Bowman, J. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy in the Treatment of Anxiety: A Systematic Review. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2013, 33, 965–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mackintosh, N.J.; Davis, R.E.; Easter, A.; Rayment-Jones, H.; Sevdalis, N.; Wilson, S.; Adams, M.; Sandall, J. Interventions to Increase Patient and Family Involvement in Escalation of Care for Acute Life-Threatening Illness in Community Health and Hospital Settings. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2020, 2020, CD012829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öst, L.-G. The Efficacy of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy: An Updated Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Behav. Res. Ther. 2014, 61, 105–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, F.; Zhou, Q.; Wu, J.; Xu, X. Effect of Group-Based Acceptance and Commitment Therapy on Older Stroke Survivors: Study Protocol for a Randomized Controlled Trial. BMC Complement. Med. Ther. 2023, 23, 353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Udvardi, V.; Szabó, G.; Fazekas, G. A Tudatos Jelenlét Alapú Beavatkozások Hatásai a Stroke Utáni Rehabilitációban. Ideggyogy. Sz. 2023, 76, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sterne, J.A.C.; Savović, J.; Page, M.J.; Elbers, R.G.; Blencowe, N.S.; Boutron, I.; Cates, C.J.; Cheng, H.-Y.; Corbett, M.S.; Eldridge, S.M.; et al. RoB 2: A Revised Tool for Assessing Risk of Bias in Randomised Trials. BMJ 2019, 366, l4898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higgins, J.P.T.; Morgan, R.L.; Rooney, A.A.; Taylor, K.W.; Thayer, K.A.; Silva, R.A.; Lemeris, C.; Akl, E.A.; Bateson, T.F.; Berkman, N.D.; et al. A Tool to Assess Risk of Bias in Non-Randomized Follow-up Studies of Exposure Effects (ROBINS-E). Environ. Int. 2024, 186, 108602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Latella, D.; Grimaldi, A.; Calabrò, R.S. Sexual Functioning and Sexual Health in Female Patients Following Stroke: A Scoping Review with Implications for Rehabilitation. J. Pers. Med. 2024, 14, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Hammouri, M.M.; Rababah, J.A.; Aldalaykeh, M. Exploring the Potential of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy Model in Self-care Behaviour in Persons with Heart Failure. Nurs. Open 2020, 7, 1560–1567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmadi Ghahnaviyeh, L.; Bagherian, B.; Feizi, A.; Afshari, A.; Mostafavi Darani, F. The Effectiveness of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy on Quality of Life in a Patient with Myocardial Infarction: A Randomized Control Trial. Iran. J. Psychiatry 2020, 15, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheibani, H.; Sheibani, K.A.; Amreei, N.N.; Masrour, M.J. An Investigation of the Effects of the Acceptance and Commitment Therapy in Groups on the Cognitive Strategies of Emotion Regulation and Self-Control in Coronary Heart Disease Patients. J. Med. Life 2019, 12, 361–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fattahi, A.; Mazini, F.; Jaberghaderi, N.; Rajabi, F.; Derakhshani, M.; Laki, M. Effectiveness of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy upon Distress, Emotion Regulation, and Self-Compassion in Patients with Cardiovascular Disease: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Trends Psychiatry Psychother. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Large, R.; Samuel, V.; Morris, R. A Changed Reality: Experience of an Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) Group after Stroke. Neuropsychol. Rehabil. 2020, 30, 1477–1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Celano, C.M.; Daunis, D.J.; Lokko, H.N.; Campbell, K.A.; Huffman, J.C. Anxiety Disorders and Cardiovascular Disease. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2016, 18, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dindo, L.; Van Liew, J.R.; Arch, J.J. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy: A Transdiagnostic Behavioral Intervention for Mental Health and Medical Conditions. Neurotherapeutics. 2017, 14, 546–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McPhillips, R.; Salmon, P.; Wells, A.; Fisher, P. Cardiac Rehabilitation Patients’ Accounts of Their Emotional Distress and Psychological Needs: A Qualitative Study. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2019, 8, e011117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, C.-Q.; Leeming, E.; Smith, P.; Chung, P.-K.; Hagger, M.S.; Hayes, S.C. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy for Health Behavior Change: A Contextually-Driven Approach. Front. Psychol. 2018, 8, 2350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kubzansky, L.D.; Huffman, J.C.; Boehm, J.K.; Hernandez, R.; Kim, E.S.; Koga, H.K.; Feig, E.H.; Lloyd-Jones, D.M.; Seligman, M.E.P.; Labarthe, D.R. Positive Psychological Well-Being and Cardiovascular Disease: JACC Health Promotion Series. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2018, 72, 1382–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rashidi, A.; Whitehead, L.; Newson, L.; Astin, F.; Gill, P.; Lane, D.A.; Lip, G.Y.H.; Neubeck, L.; Ski, C.F.; Thompson, D.R.; et al. The Role of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy in Cardiovascular and Diabetes Healthcare: A Scoping Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 8126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdollahi, S.M.; Rafiepoor, A.; Sabet, M. The Effectiveness of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy on Mental Health, Hopefulness and Meaningfulness in People with Cardiovascular Disease. Iran. J. Health Psychol. 2020, 3, 61–70. [Google Scholar]

- McCracken, L.M.; Vowles, K.E. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy and Mindfulness for Chronic Pain: Model, Process, and Progress. Am. Psychol. 2014, 69, 178–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zettle, R.D. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy for Depression. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2015, 2, 65–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study | Design | Population | Objective | Intervention | Results | Statistical Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Al-Hammouri et al., 2020 [37] | Exploratory cross-sectional | 165 participants with heart failure | Explore the effect of ACT on the self-care behavior of individuals with heart failure. | ACT model for self-care behavior | Mindfulness and committed action play a significant role in self-care behavior for people with heart failure, but cognitive fusion does not have a direct impact. | Significant bivariate correlations (r = 0.18–0.25, p < 0.05–0.001); Regression Model 2 F(5,159) = 3.88, p < 0.01; significant predictors: mindfulness, committed action; effect size and power: NR |

| Ghahnaviyeh et al., 2020 [38] | Controlled clinical trial | 60 patients with MI randomly divided into EG and CG. | Evaluate the impact of ACT on the psychological flexibility and overall QoL of MI patients. | ACT for EG, no intervention for CG. | EG showed a noteworthy improvement in their QoL and in subscales related to their mental and physical health. | Repeated measures ANOVA: all main effects p < 0.001; physical QoL interaction p = 0.03; effect size and power: NR |

| Sheibani et al., 2019 [39] | Quasi-experimental with a pretest-posttest design | 30 patients with coronary heart disease randomly divided into EG and CG. | Examine the effect of group-based ACT on cognitive strategies used by patients with CVDs for emotion regulation and self-control. | Hayes’ ACT for EG, no intervention for CG. | The treatment increased positive coping strategies and decreased negative ones in cardiovascular patients, but self-control did not show significant changes. | Wilks’ Lambda F(3,23) = 85.3, p = 0.023, η2 = 0.33, power = 0.75; Positive ER p = 0.004, η2 = 0.29, power = 0.86; Negative ER p = 0.045, η2 = 0.15; Self-control n.s. |

| Fattahi A et al., 2023 [40] | Randomized clinical trial | 40 CVD patients randomly divided into EG and CG. | Examine how ACT affects distress, emotion regulation, and self-compassion in CVDs patients. | ACT for EG, cardiovascular drugs for CG | ACT decreased depression, anxiety, and stress while boosting self-compassion and emotion regulation. | Mixed ANOVA: significant effects for all variables (p < 0.05); effect strongest for stress; η2 and power NR |

| Large R et al., 2020 [41] | Qualitative | 13 post-stroke participants | Investigate how ACT can help survivors coping with residual stroke symptoms. | Didactic ACT group sessions. | ACT helped survivors accept symptoms and adjust to limitations. It has shown potential as a psychological intervention for those experiencing distress. | Qualitative study; no statistical data applicable; 6 themes identified (e.g., acceptance, peer support, emotional flexibility) |

| Study | Country | Delivery Mode | Number of Sessions | Session Duration | Therapist Qualifications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Al-Hammouri et al. (2020) [37] | Jordan | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| Ghahnaviyeh et al. (2020) [38] | Iran | Face-to-face | 8 | 90 min | Clinical Psychologist |

| Sheibani et al. (2019) [39] | Iran | Group-based, face-to-face | 8 | 90 min | Not reported |

| Fattahi et al. (2023) [40] | Iran | Group-based, face-to-face | 8 weekly sessions | Not specified | Clinical Psychologist |

| Large et al. (2020) [41] | UK | Group-based, face-to-face | 8 | Not reported | Chartered Clinical Psychologist |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Grimaldi, A.; Veneziani, I.; Culicetto, L.; Quartarone, A.; Calabrò, R.S.; Latella, D. Effectiveness of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) in Patient with Cardiovascular Disease: A Systematic Review. Healthcare 2025, 13, 1831. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13151831

Grimaldi A, Veneziani I, Culicetto L, Quartarone A, Calabrò RS, Latella D. Effectiveness of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) in Patient with Cardiovascular Disease: A Systematic Review. Healthcare. 2025; 13(15):1831. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13151831

Chicago/Turabian StyleGrimaldi, Alessandro, Isabella Veneziani, Laura Culicetto, Angelo Quartarone, Rocco Salvatore Calabrò, and Desirèe Latella. 2025. "Effectiveness of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) in Patient with Cardiovascular Disease: A Systematic Review" Healthcare 13, no. 15: 1831. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13151831

APA StyleGrimaldi, A., Veneziani, I., Culicetto, L., Quartarone, A., Calabrò, R. S., & Latella, D. (2025). Effectiveness of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) in Patient with Cardiovascular Disease: A Systematic Review. Healthcare, 13(15), 1831. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13151831