Using Implementation Theories to Tailor International Clinical Guidelines for Post-Stroke Gait Disorders

Abstract

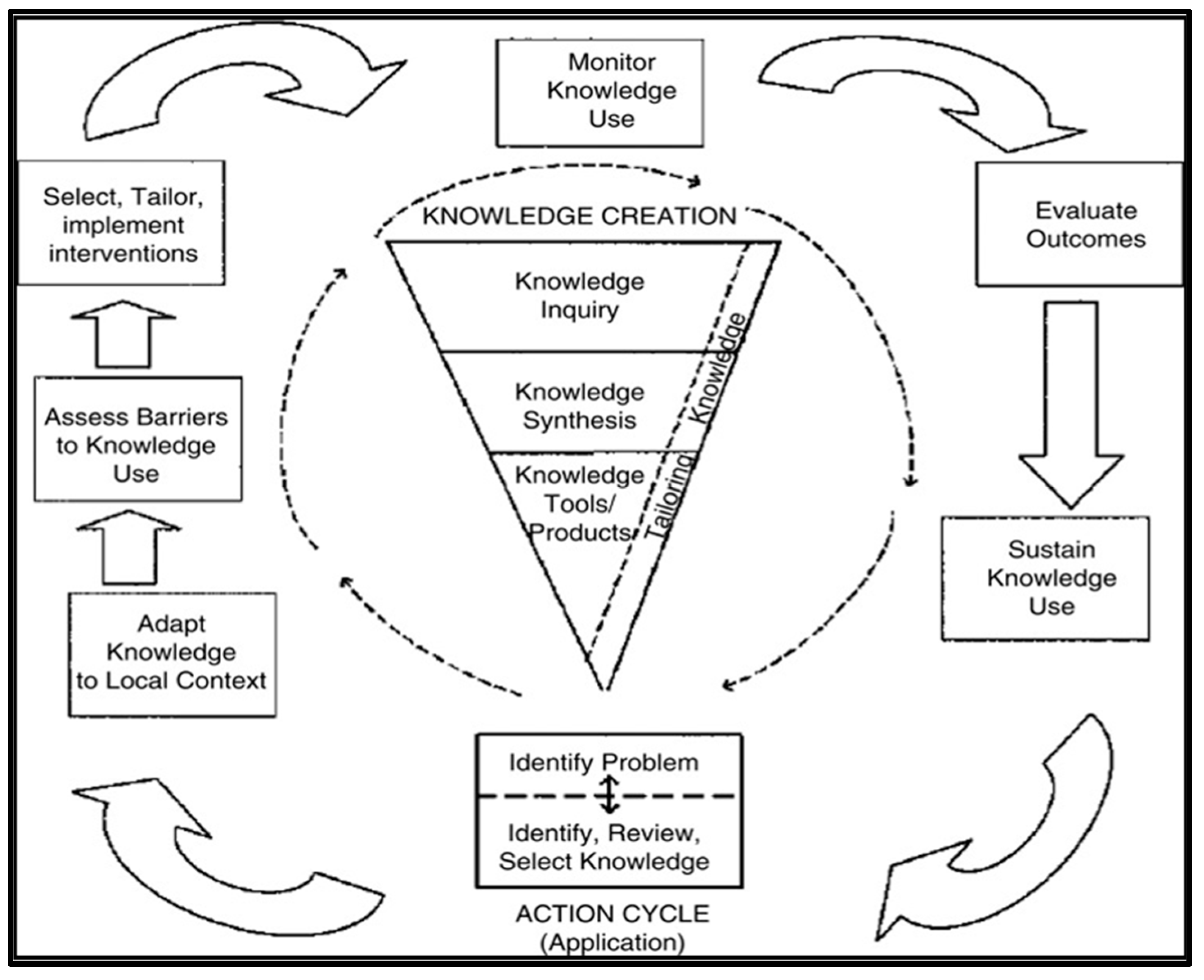

1. Introduction

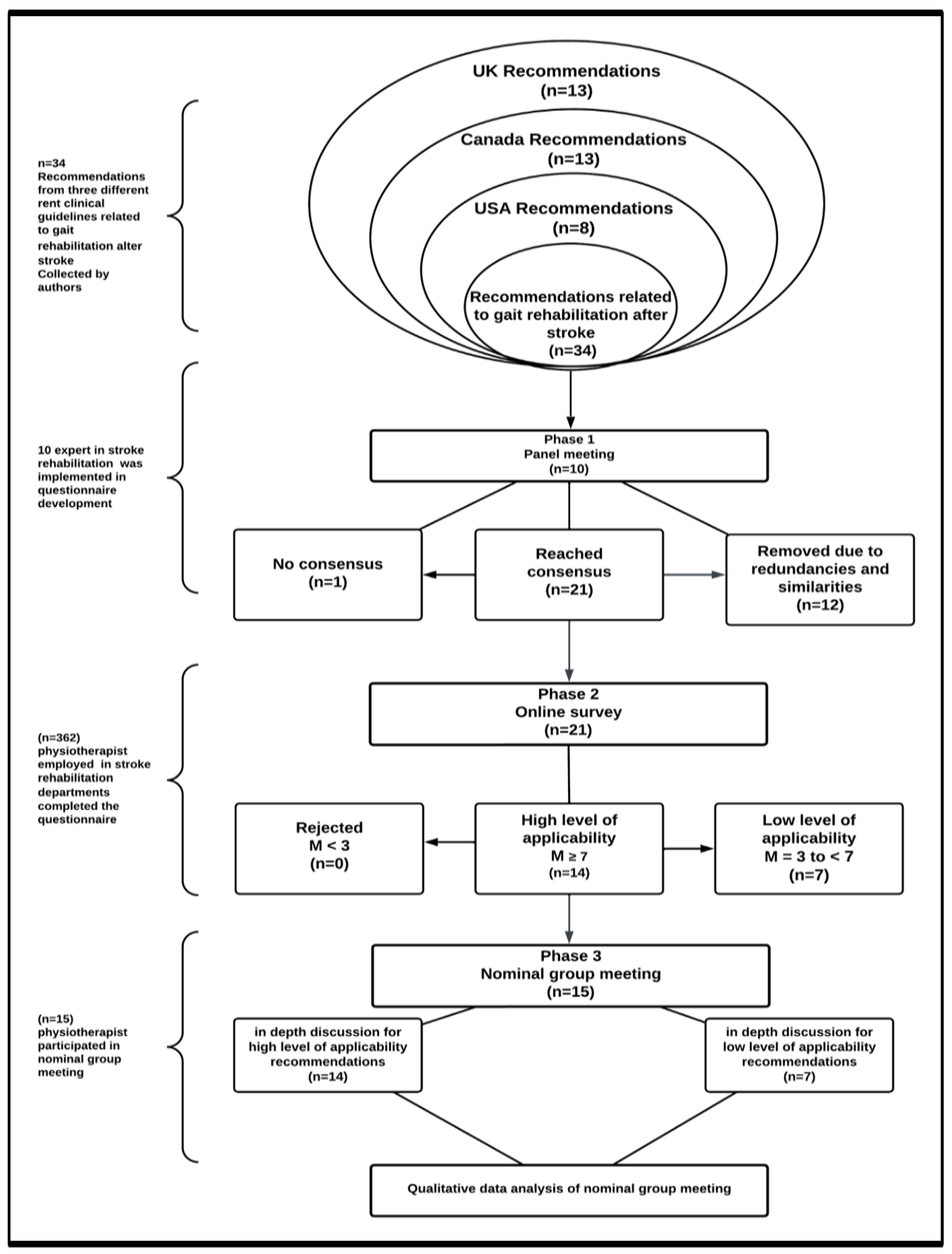

2. Methods

2.1. Phase 1: The Panel Phase

2.1.1. The Sample Size

2.1.2. The Procedure

2.1.3. Data Analysis

2.2. Phase 2: The Survey

2.2.1. The Sample Size

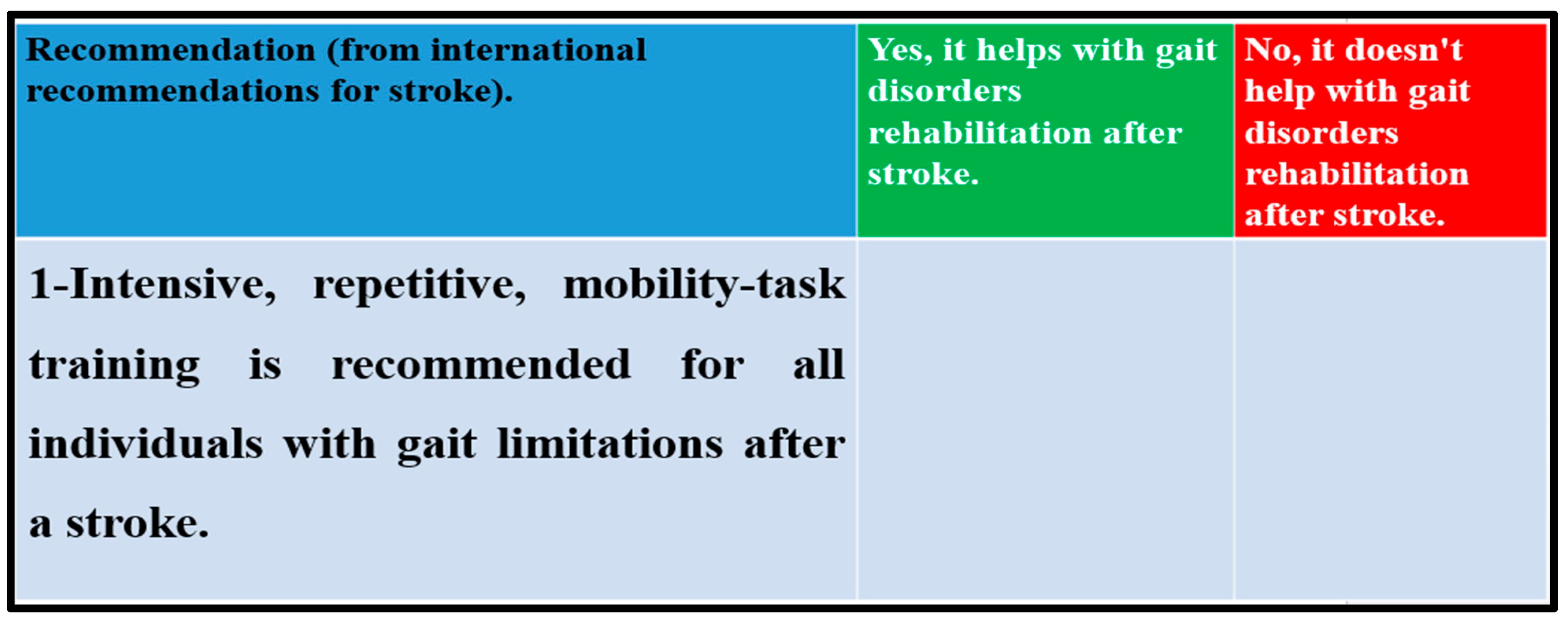

2.2.2. The Procedure

2.2.3. Data Analysis

2.3. Phase 3: Nominal Group Meeting

2.3.1. The Sample Size

2.3.2. The Procedure

2.3.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Result of Phase 1: Panel Meeting

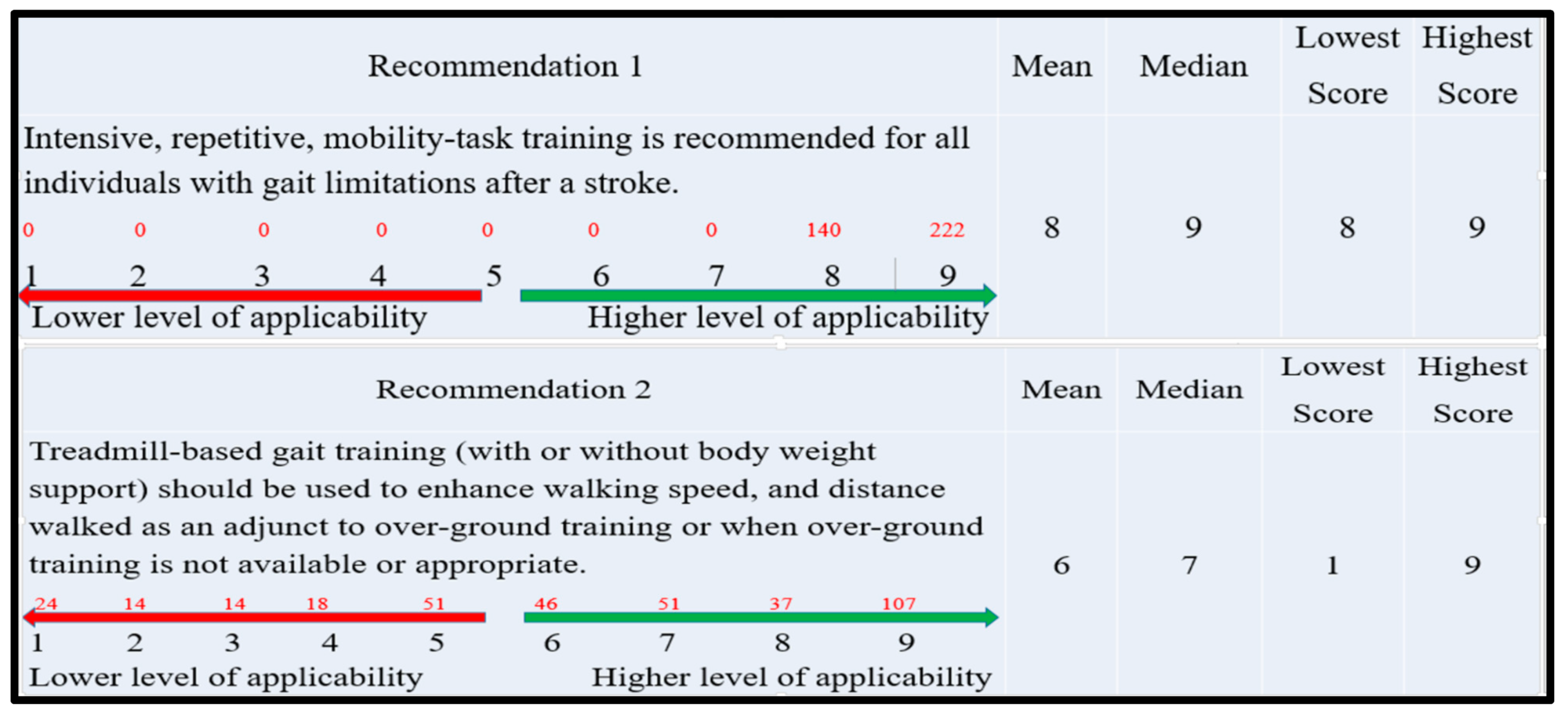

3.2. Result of Phase 2: Online Survey

3.3. Results of Phase 3: Nominal Group Meeting (NMG)

3.3.1. Organizational Factors

“I recognize the significance of this recommendation for stroke gait rehabilitation; however, my department does not have the necessary equipment to implement it. I voted 5 out of 9.”

“This recommendation does not require any equipment; it depends instead on the professional’s skill. In my opinion, these comments may help clarify the rationale for achieving a median value of 9.”

“I rated some recommendations based on departmental teamwork and communication. This fosters knowledge exchange, which contributes to the development of optimal practices.”

“In my opinion, certain recommendations may be feasible and could be implemented”. However, rigid organizational policies can obstruct the effective application of evidence in real-world clinical settings.”

3.3.2. Individual Clinician Factors

“Individuals lacking sufficient expertise, practical experience, skills, and training may have a limited understanding of recommendation effectiveness in producing favorable results with patients.”

“If the recommendation is not being utilized, it is unlikely that one would use it on a daily basis.”

3.3.3. Patient Factors

“Before considering the implementation of any recommendations for my patient, I took into account medical problems related to strokes, as well as memory and cognitive issues that affect individuals who have experienced a stroke.”

“When deciding which recommendations to incorporate into my practice, I considered how I could effectively engage with my patients in meaningful discussions and provide clear explanations about this recommendation to ensure that interventions align with their values, preferences, and goals.”

3.3.4. Other Factors

“The strict inclusion and exclusion criteria of a randomized controlled trial (RCT) may exclude the patients I am trying to treat. Therefore, increasing the use of qualitative methods may be beneficial.”

“For me, in the early stages, I occasionally focused on the prevention of secondary complications, whereas in the late stages, I used to focus on the improvement of motor function.”

4. Discussion

4.1. Organizational Factors

4.2. Individual Clinician Factors

4.3. Patient Factors

4.4. Other Factors

5. Study Limitations

6. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Nominal Group Meeting Guide

- Thank participants for participating and explain the purpose of the Study.

- Introduce self.

- Explain the nominal group meeting process.

- Part 1 questions

- Part 2 questions

- Part 3 questions

Appendix B. Final Codes

| # | Code | Description |

| 1 | Patient characteristics | Individual patient characteristics such as age, sex, medical history, comorbidities, and genetic factors can influence the tailoring of evidence-based practices. Different patient populations may respond differently to treatments, so considering these factors is essential in tailoring evidence to meet individual patient needs. |

| 2 | Clinical context | The specific clinical context, including the healthcare setting, available resources, and local guidelines, can influence the tailoring of evidence. The feasibility and applicability of certain interventions may vary depending on the resources and infrastructure available in a particular healthcare setting. |

| 3 | Disease severity and stage | The severity and stage of the disease can impact the tailoring of evidence-based practices. The evidence supporting a particular intervention may differ based on the disease’s severity and stage, and treatment decisions may need to be adjusted accordingly. |

| 4 | Coexisting conditions | Patients often have multiple medical conditions, and the presence of coexisting conditions can influence treatment decisions. Tailoring evidence-based practices requires considering the impact of treatment on all coexisting conditions to ensure the best outcomes for the patient. |

| 5 | Patient preferences and values | Patient preferences, values, and goals play a crucial role in tailoring evidence-based practices. Shared decision-making between healthcare providers and patients is important to understand patient preferences and incorporate them into the treatment plan. |

| 6 | Emerging research | Clinical practice is dynamic, and new research findings continuously emerge. As new evidence becomes available, it may prompt modifications in existing practices. Staying updated with the latest research and integrating it into clinical decision-making is essential for tailoring evidence-based practices. |

| 7 | Clinical expertise | The clinical expertise and experience of healthcare providers are vital in tailoring evidence-based practices. Providers need to integrate their knowledge and experience with the available evidence to develop individualized treatment plans for patients. |

| 8 | Cost and resource considerations | The cost-effectiveness and availability of resources can influence the tailoring of evidence-based practices. In resource-limited settings, healthcare providers may need to adapt interventions to make them more feasible and cost-effective. |

| 9 | Cultural and societal factors | Cultural and societal factors can influence the tailoring of evidence-based practices. Medical practices and beliefs may vary across different cultures and communities, and healthcare providers need to consider these factors when tailoring evidence to individual patients. Cultural beliefs, values, and preferences can impact treatment decisions and adherence to therapies. |

| 10 | Risk-benefit assessment | The assessment of risks and benefits associated with a particular intervention is crucial in tailoring evidence-based practices. Healthcare providers need to evaluate the potential benefits of a treatment against the risks and potential harms, taking into account individual patient characteristics and circumstances. |

| 11 | Guidelines and recommendations | Clinical practice guidelines and recommendations provided by professional medical organizations are important sources of evidence-based information. These guidelines often synthesize the available evidence and provide recommendations for specific conditions or interventions. Healthcare providers may use these guidelines as a framework for tailoring evidence-based practices. |

| 12 | Patient education and health Literacy | Tailoring evidence-based practices requires effective communication and patient education. Health literacy, the ability of patients to understand and utilize health information, plays a critical role in the implementation of evidence-based practices. Healthcare providers should ensure that patients have access to accurate and understandable information to make informed decisions about their care. |

| 13 | Health system factors | The structure and organization of the healthcare system can influence the tailoring of evidence-based practices. Factors such as reimbursement policies, healthcare regulations, and the availability of electronic health records can impact the implementation and customization of evidence-based practices within a healthcare system. |

| 14 | Time and resource constraints | Healthcare providers often face time constraints in clinical practice. The availability of resources, including time for patient consultations and access to necessary diagnostic tests and treatments, can impact the tailoring of evidence-based practices. Providers need to balance the available resources with the best available evidence to provide optimal care within the given constraints. |

| 15 | Clinical trial limitations | The evidence base for clinical practice is primarily derived from clinical trials and research studies. However, clinical trials have limitations, such as specific inclusion and exclusion criteria, limited sample sizes, and relatively short follow-up periods. Healthcare providers need to consider these limitations when tailoring evidence-based practices and should be cautious about generalizing the findings to diverse patient populations. |

| 16 | Ethical considerations | Ethical principles, such as autonomy, beneficence, non-maleficence, and justice, play a significant role in tailoring evidence-based practices. Healthcare providers need to consider the ethical implications of treatment decisions, respecting patient autonomy and ensuring that the chosen interventions align with ethical standards. |

| 17 | Patient outcomes and preferences | The desired outcomes and preferences of individual patients are crucial in tailoring evidence-based practices. Healthcare providers need to consider what outcomes are most important to the patient, such as symptom relief, functional improvement, quality of life, or long-term survival. Understanding patient preferences allows for shared decision-making and the customization of treatments accordingly. |

| 18 | Feedback and continuous learning | Tailoring evidence-based practices requires a commitment to continuous learning and improvement. Healthcare providers should actively seek feedback from patients, colleagues, and interdisciplinary teams to evaluate the effectiveness and impact of interventions. This feedback loop helps refine and adapt practices over time to optimize patient outcomes. |

| 19 | Patient safety and risk management | Patient safety is a fundamental consideration when tailoring evidence-based practices. Healthcare providers need to assess and mitigate potential risks associated with interventions, including adverse effects, drug interactions, and medical errors. Incorporating risk management strategies into the tailoring process ensures patient safety and minimizes harm. |

| 20 | Interdisciplinary collaboration | Tailoring evidence-based practices often requires collaboration among healthcare professionals from different disciplines. Interdisciplinary teamwork allows for a comprehensive assessment of patient needs and the integration of diverse perspectives and expertise. Collaborative decision-making can lead to more effective tailoring of evidence-based practices. |

| 21 | Patient advocacy and empowerment | Patient advocacy and empowerment are crucial in the tailoring of evidence-based practices. Encouraging patients to actively participate in their care, providing education and resources, and supporting their autonomy and decision-making process empower patients to make informed choices and actively engage in their treatment. |

| 22 | Health policy and reimbursement systems | Health policy and reimbursement systems can shape the tailoring of evidence-based practices. National or local healthcare policies, insurance coverage policies, and reimbursement mechanisms may impact the availability and accessibility of certain interventions. Healthcare providers need to navigate these systems to ensure appropriate reimbursement and optimize patient access to evidence-based care. |

| 23 | Education and training | Education and training of healthcare providers are critical in the tailoring of evidence-based practices. Continuous professional development ensures that healthcare providers stay updated with the latest evidence, guidelines, and best practices. Training programs can also focus on enhancing skills in critical appraisal of evidence, shared decision-making, and the application of tailored approaches in clinical practice. |

| 24 | Patient engagement and shared decision-making | Patient engagement and shared decision-making are integral to the tailoring of evidence-based practices. Involving patients in the decision-making process promotes patient-centered care and ensures that interventions align with their values, preferences, and goals. Shared decision-making facilitates the customization of evidence-based practices to meet the unique needs of each patient. |

| 25 | Feedback from clinical experience | Clinical experience and feedback play a vital role in refining and tailoring evidence-based practices. Healthcare providers continuously learn from their own experiences and the experiences of colleagues. They can adapt and modify interventions based on real-world outcomes, patient responses, and emerging evidence to optimize the tailoring of evidence-based practices. |

| 26 | Multimorbidity and comorbidities | Many patients have multiple chronic conditions, known as multimorbidity, or comorbidities, where they have one or more additional health conditions alongside their primary condition. Tailoring evidence-based practices becomes complex in such cases as the management of one condition may affect the management of others. Healthcare providers need to carefully consider the interactions and potential conflicts among treatments to ensure optimal outcomes and minimize harm. |

| 27 | Health behavior and psychological factors | Tailoring evidence-based practices requires considering the health behaviors and psychological factors that influence patient engagement and adherence to treatments. Factors such as motivation, beliefs, social support, and mental health can impact a patient’s ability to follow recommended interventions. Healthcare providers should assess and address these factors to enhance treatment outcomes. |

| 28 | Interprofessional collaboration | Collaborative teamwork among healthcare professionals is crucial in tailoring evidence-based practices. Interprofessional collaboration involves communication, coordination, and shared decision-making among professionals from different disciplines, such as physicians, nurses, pharmacists, and allied health professionals. This collaboration allows for a comprehensive assessment of patient needs and the integration of diverse perspectives in tailoring care. |

| 29 | Environmental and occupational factors | Tailoring evidence-based practices may involve considering environmental and occupational factors that impact a patient’s health. For example, healthcare providers may need to consider workplace conditions, or access to clean air and water when tailoring interventions. Addressing these factors can contribute to improved health outcomes and the prevention of occupational and environmental diseases. |

| 30 | Health system resources and constraints | Tailoring evidence-based practices can be influenced by the available resources and constraints within the healthcare system. Factors such as limited funding, workforce shortages, time constraints, and competing priorities can impact the extent to which practices can be tailored. Healthcare providers must navigate these challenges and find ways to optimize tailoring within the resource constraints. |

| Clarifying question | Clarification on a certain issue in question. | |

| Unrelated discussion | The discussion presented is not directly relevant to the research questions at hand. |

Appendix C. The Degree of Agreement (Consensus) on Recommendations

| Recommendation 1 | Mean | Median | Lowest Score | Highest Score | ||||||||

| Intensive, repetitive, mobility-task training is recommended for all individuals with gait limitations after a stroke. | 8 | 9 | 8 | 9 | ||||||||

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 140 | 222 | ||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | ||||

| Lower level of applicability | higher level of applicability | |||||||||||

| Recommendation 2 | Mean | Median | Lowest Score | Highest Score | ||||||||

| Treadmill-based gait training (with or without body weight support) should be used to enhance walking speed, and distance walked as an adjunct to over-ground training or when over-ground training is not available or appropriate. | 6 | 7 | 1 | 9 | ||||||||

| 24 | 14 | 14 | 18 | 51 | 46 | 51 | 37 | 107 | ||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | ||||

| lower level of applicability | higher level of applicability | |||||||||||

| Recommendation 3 | Mean | Median | Lowest Score | Highest Score | ||||||||

| Mechanically assisted walking (treadmill, electromechanical gait trainer, robotic device, servo-motor) with body weight support may be considered for patients who are nonambulatory or have low ambulatory ability early after stroke. | 5 | 5 | 1 | 9 | ||||||||

| 46 | 23 | 37 | 28 | 56 | 24 | 46 | 46 | 56 | ||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | ||||

| lower level of applicability | higher level of applicability | |||||||||||

| Recommendation 4 | Mean | Median | Lowest Score | Highest Score | ||||||||

| Robot-assisted movement training to improve motor function and mobility after stroke in combination with conventional therapy may be considered | 5 | 5 | 1 | 9 | ||||||||

| 56 | 33 | 14 | 37 | 42 | 14 | 37 | 50 | 79 | ||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | ||||

| lower level of applicability | higher level of applicability | |||||||||||

| Recommendation 5 | Mean | Median | Lowest Score | Highest Score | ||||||||

| People with stroke who are able to walk (albeit with the assistance of other people or assistive devices) and who wish to improve their mobility at any stage after stroke should be offered access to equipment to enable intensive walking training such as treadmills or electromechanical gait trainers. To achieve this, training needs to be at 60-85% heart rate reserve (by adjustment of inclination or speed) for at least 40 min, three times a week for 10 weeks. | 4 | 5 | 1 | 9 | ||||||||

| 81 | 23 | 14 | 23 | 79 | 22 | 13 | 41 | 66 | ||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | ||||

| lower level of applicability | higher level of applicability | |||||||||||

| Recommendation 6 | Mean | Median | Lowest Score | Highest Score | ||||||||

| Practice walking with either a treadmill (with or without body-weight support) or overground walking exercise training combined with conventional rehabilitation may be reasonable for recovery of walking function. | 7 | 8 | 1 | 9 | ||||||||

| 9 | 9 | 28 | 14 | 18 | 18 | 74 | 37 | 155 | ||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | ||||

| lower level of applicability | higher level of applicability | |||||||||||

| Recommendation 7 | Mean | Median | Lowest Score | Highest Score | ||||||||

| incorporating cardiovascular exercise and strengthening interventions is reasonable to consider for recovery of gait capacity and gait-related mobility tasks. | 7 | 8 | 1 | 9 | ||||||||

| 9 | 5 | 14 | 28 | 23 | 23 | 70 | 70 | 120 | ||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | ||||

| lower level of applicability | higher level of applicability | |||||||||||

| Recommendation 8 | Mean | Median | Lowest Score | Highest Score | ||||||||

| Biofeedback, in the form of visual and/or auditory signals to indicate unequal weight bearing and timing, can be used to enhance gait training and improve functional recovery. | 8 | 7 | 8 | 9 | ||||||||

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 232 | 130 | ||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | ||||

| lower level of applicability | higher level of applicability | |||||||||||

| Recommendation 9 | Mean | Median | Lowest Score | Highest Score | ||||||||

| Virtual reality training (such as non-immersive technologies) could be considered as an adjunct to conventional gait training. | 5 | 5 | 1 | 9 | ||||||||

| 13 | 5 | 28 | 42 | 28 | 28 | 51 | 51 | 115 | ||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | ||||

| lower level of applicability | higher level of applicability | |||||||||||

| Recommendation 10 | Mean | Median | Lowest Score | Highest Score | ||||||||

| Rhythmic auditory stimulation (RAS) should be considered for improving gait parameters in stroke patients, including gait velocity, cadence, stride length, and gait symmetry. | 5 | 6 | 1 | 9 | ||||||||

| 41 | 14 | 20 | 46 | 37 | 51 | 51 | 32 | 70 | ||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | ||||

| lower level of applicability | higher level of applicability | |||||||||||

| Recommendation 11 | Mean | Median | Lowest Score | Highest Score | ||||||||

| Group therapy with circuit training is a reasonable approach to improve walking. | 8 | 9 | 8 | 9 | ||||||||

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 138 | 224 | ||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | ||||

| lower level of applicability | higher level of applicability | |||||||||||

| Recommendation 12 | Mean | Median | Lowest Score | Highest Score | ||||||||

| Mental Practice should be considered as an adjunct to lower extremity motor retraining | 6 | 7 | 1 | 9 | ||||||||

| 18 | 9 | 32 | 23 | 47 | 47 | 47 | 56 | 83 | ||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | ||||

| lower level of applicability | higher level of applicability | |||||||||||

| Recommendation 13 | Mean | Median | Lowest Score | Highest Score | ||||||||

| People with stroke with limited ankle/foot stability or limited dorsiflexion (‘foot drop’) that impedes mobility or confidence should be offered an ankle-foot orthosis (using a lightweight, flexible orthosis in the first instance) or functional electrical stimulation to improve walking and balance, including referral to orthotics if required. | 7 | 8 | 1 | 9 | ||||||||

| 14 | 0 | 23 | 14 | 46 | 23 | 46 | 41 | 155 | ||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | ||||

| lower level of applicability | higher level of applicability | |||||||||||

| Recommendation 14 | Mean | Median | Lowest Score | Highest Score | ||||||||

| Any orthosis or electrical stimulation device should be evaluated and individually fitted before long-term use. | 8 | 8 | 8 | 9 | ||||||||

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 184 | 178 | ||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | ||||

| lower level of applicability | higher level of applicability | |||||||||||

| Recommendation 15 | Mean | Median | Lowest Score | Highest Score | ||||||||

| People using an orthosis after stroke should be educated about the risk of pressure damage from their orthosis, especially if sensory loss is present in addition to weakness. Services should provide timely access for orthotic repairs and adaptations. | 8 | 8 | 8 | 9 | ||||||||

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 189 | 173 | ||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | ||||

| lower level of applicability | higher level of applicability | |||||||||||

| Recommendation 16 | Mean | Median | Lowest Score | Highest Score | ||||||||

| Functional electrical stimulation (FES) should be used to improve strength and function (gait) in selected patients, but the effects may not be sustained. | 5 | 6 | 1 | 9 | ||||||||

| 37 | 15 | 24 | 32 | 60 | 70 | 46 | 60 | 18 | ||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | ||||

| lower level of applicability | higher level of applicability | |||||||||||

| Recommendation 17 | Mean | Median | Lowest Score | Highest Score | ||||||||

| The person with stroke, their family/carers, and clinicians in all settings should be trained in the safe application and use of orthoses and electrical stimulation devices. | 8 | 8 | 7 | 9 | ||||||||

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 101 | 107 | 154 | ||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | ||||

| lower level of applicability | higher level of applicability | |||||||||||

| Recommendation 18 | Mean | Median | Lowest Score | Highest Score | ||||||||

| Stroke services should have local protocols and agreements in place to ensure specialist assessment, evaluation, and follow-up is available for long-term functional electrical stimulation use. | 6 | 7 | 1 | 9 | ||||||||

| 32 | 9 | 14 | 14 | 51 | 46 | 37 | 56 | 103 | ||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | ||||

| lower level of applicability | higher level of applicability | |||||||||||

| Recommendation 19 | Mean | Median | Lowest Score | Highest Score | ||||||||

| People with limited mobility after stroke should be assessed for, provided with, and trained to use appropriate mobility aids, including a wheelchair, to enable safe independent mobility. | 7 | 8 | 1 | 9 | ||||||||

| 5 | 0 | 9 | 24 | 32 | 18 | 24 | 74 | 176 | ||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | ||||

| lower level of applicability | higher level of applicability | |||||||||||

| Recommendation 20 | Mean | Median | Lowest Score | Highest Score | ||||||||

| People with stroke who are mobile should be assessed for real-world walking such as road crossing, walking on uneven ground, over distances and inclines. This should include assessment of the impact of dual tasking, neglect, vision, and confidence in busy environments. | 6 | 8 | 1 | 9 | ||||||||

| 9 | 5 | 28 | 23 | 37 | 32 | 37 | 32 | 159 | ||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | ||||

| lower level of applicability | higher level of applicability | |||||||||||

| Recommendation 21 | Mean | Median | Lowest Score | Highest Score | ||||||||

| Clinicians should not use risk assessment protocols that limit training for fear of cardiovascular or other adverse events, given the good safety record of repetitive gait training however it is delivered. | 5 | 6 | 1 | 9 | ||||||||

| 56 | 9 | 32 | 28 | 46 | 60 | 37 | 37 | 57 | ||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | ||||

| lower level of applicability | higher level of applicability | |||||||||||

References

- Guerra-Farfan, E.; Garcia-Sanchez, Y.; Jornet-Gibert, M.; Nunez, J.H.; Balaguer-Castro, M.; Madden, K. Clinical practice guidelines: The good, the bad, and the ugly. Injury 2023, 54, S26–S29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nilsen, E.S.; Myrhaug, H.T.; Johansen, M.; Oliver, S.; Oxman, A.D. Methods of consumer involvement in developing healthcare policy and research, clinical practice guidelines and patient information material. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2006, 3, CD004563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Guidelines for Clinical Practice: From Development to Use; Field, M.J., Lohr, K.N., Eds.; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- American Heart Association. Available online: https://www.heart.org/ (accessed on 25 May 2025).

- American Stroke Association. Available online: https://www.stroke.org/en/ (accessed on 25 May 2025).

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Available online: https://www.nice.org.uk/ (accessed on 25 May 2025).

- The Canadian Stroke Best Practices Recommendations. Available online: https://www.strokebestpractices.ca/ (accessed on 25 May 2025).

- Duncan, P.W.; Zorowitz, R.; Bates, B.; Choi, J.Y.; Glasberg, J.J.; Graham, G.D.; Katz, R.C.; Lamberty, K.; Reker, D. Management of Adult Stroke Rehabilitation Care: A Clinical Practice Guideline. Stroke 2005, 36, e100–e143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arboix, A.; Arbe, G.; García-Eroles, L.; Oliveres, M.; Parra, O.; Massons, J. Infarctions in the vascular territory of the posterior cerebral artery: Clinical features in 232 patients. BMC Res. Notes 2011, 4, 329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsandila-Kalakou, F.; Wiig, S.; Aase, K. Factors contributing to healthcare professionals’ adaptive capacity with hospital standardization: A scoping review. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2023, 23, 799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kakeeto, M.; Lundmark, R.; Hasson, H.; von Thiele Schwarz, U. Meeting patient needs trumps adherence. A cross-sectional study of adherence and adaptations when national guidelines are used in practice. J. Eval. Clin. Pract. 2017, 23, 830–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McHugh, S.M.; Riordan, F.; Kerins, C.; Curran, G.; Lewis, C.C.; Presseau, J.; Powell, B.J. Understanding tailoring to support the implementation of evidence-based interventions in healthcare: The CUSTOMISE research programme protocol. HRB Open Res. 2023, 6, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rowe, D.A.; Collier-Meek, M.A.; Kittelman, A.; Pierce, J. Ensuring effective implementation of evidence-based practices. Teach. Except. Child. 2021, 53, 396–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escoffery, C.; Lebow-Skelley, E.; Haardoerfer, R. A systematic review of adaptations of evidence-based public health interventions globally. Implement. Sci. 2018, 13, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Logan, J.; Graham, I.D. Toward a Comprehensive Interdisciplinary Model of Health Care Research Use. Sci. Commun. 1998, 20, 227–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitson, A.; Harvey, G.; McCormack, B. Enabling the implementation of evidence based practice: A conceptual framework. Qual. Health Care QHC 1998, 7, 149–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graham, I.D.; Logan, J.; Harrison, M.B.; Straus, S.E.; Tetroe, J.; Caswell, W.; Robinson, N. Lost in knowledge translation: Time for a map? J. Contin. Educ. Health Prof. 2006, 26, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, A.; Jackson, A.; Jordan, J.; Hammersley, S.; Hill, J.; Mercer, C.; Smith, C.; Thompson, J.; Woby, S.; Hudson, A. Clinical Guidelines for the Physiotherapy Management of Whiplash Associated Disorder; Chartered Society of Physiotherapy: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Rycroft-Malone, J. Formal consensus: The development of a national clinical guideline. BMJ Qual. Saf. 2001, 10, 238–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rycroft-Malone, J.; Bucknall, T. Using theory and frameworks to facilitate the implementation of evidence into practice. Worldviews Evid.-Based Nurs. 2010, 7, 57–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira, V.C.; Silva, S.N.; Carvalho, V.K.; Zanghelini, F.; Barreto, J.O. Strategies for the implementation of clinical practice guidelines in public health: An overview of systematic reviews. Health Res. Policy Syst. 2022, 20, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallagher-Thompson, D.; Haley, W.; Guy, D.; Rupert, M.; Argüelles, T.; Zeiss, L.M.; Long, C.; Tennstedt, S.; Ory, M. Tailoring psychological interventions for ethnically diverse dementia caregivers. Clin. Psychol. Sci. Pract. 2003, 10, 423–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riordan, F.; Kerins, C.; Pallin, N.; Albers, B.; Clack, L.; Morrissey, E.; Curran, G.M.; Lewis, C.C.; Powell, B.J.; Presseau, J.; et al. Characterising processes and outcomes of tailoring implementation strategies in healthcare: A protocol for a scoping review. HRB Open Res. 2002, 5, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teasell, R.; Salbach, N.M.; Foley, N.; Mountain, A.; Cameron, J.I.; Jong, A.D.; Acerra, N.E.; Bastasi, D.; Carter, S.L.; Fung, J.; et al. Canadian Stroke Best Practice Recommendations: Rehabilitation, Recovery, and Community Participation following Stroke. Part One: Rehabilitation and Recovery Following Stroke; 6th Edition Update 2019. Int. J. Stroke Off. J. Int. Stroke Soc. 2020, 15, 763–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harrison, M.B.; Légaré, F.; Graham, I.D.; Fervers, B. Adapting clinical practice guidelines to local context and assessing barriers to their use. CMAJ 2010, 182, E78–E84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bjartmarz, I.; Jonsdottir, H.; Hafsteinsdottir, T.B. Implementation and feasibility of the stroke nursing guideline in the care of patients with stroke: A mixed methods study. BMC Nurs. 2017, 16, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kendall, P.C.; Frank, H.E. Implementing evidence-based treatment protocols: Flexibility within fidelity. Clin. Psychol. Sci. Pract. 2018, 25, e12271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Current Job Title | Number of Participants | Background |

|---|---|---|

| Clinical senior physical therapist | 4 | Stroke rehabilitation |

| Clinical consultant of rehabilitation | 3 | Stroke rehabilitation |

| Professor of stroke rehabilitation | 1 | Stroke rehabilitation |

| Professor of stroke and older people’s care | 1 | Stroke rehabilitation and falls after stroke. |

| Professor of neurorehabilitation. | 1 | Exercise interventions after neurological diseases. |

| Q1: Gender | Frequency (n) | Valid Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Male | 189 | 52.2% |

| Female | 173 | 47.8% |

| Total | 362 | 100% |

| Q2: Age | ||

| 20–29 | 228 | 63% |

| 30–39 | 108 | 29.8% |

| 40–49 | 21 | 5.8% |

| ≥50 | 5 | 1.4% |

| Total | 362 | 100% |

| Q3: Qualification | ||

| Diploma | 4 | 1.1% |

| BSc | 249 | 69.8% |

| MSc | 101 | 27.9% |

| PhD | 8 | 2.2% |

| Total | 362 | 100% |

| Q4: experience | ||

| 1–5 years | 250 | 69.1% |

| 6–10 years | 40 | 11% |

| 11–15 years | 32 | 8.8% |

| ≥15 Years | 40 | 11% |

| Total | 362 | 100% |

| Q5: Patients/day | ||

| 1–5 patients | 302 | 83.4% |

| 6–10 patients | 23 | 6.4% |

| 11–15 patients | 14 | 3.9% |

| ≥15 patients | 23 | 6.4% |

| Total | 362 | 100% |

| Q6: Region | ||

| Central | 146 | 40.3% |

| East | 63 | 17.4% |

| West | 82 | 22.7% |

| North | 30 | 8.3% |

| South | 41 | 11.3% |

| Total | 362 | 100% |

| Q7: Workplace | ||

| Governmental (hospital\center) | 188 | 51.9% |

| Private (hospital/center) | 174 | 48.1% |

| Total | 362 | 100% |

| Categories | Numbers (n, %) | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 11 (73.3%) |

| Female | 4 (26.7%) | |

| Age | 20–25 | 1 (4%) |

| 26–30 | 4 (26.7%) | |

| 31–35 | 3 (20%) | |

| 36–40 | 5 (33.3%) | |

| ≥41 | 2 (13.3%) | |

| Qualification | Diploma | 0 (0%) |

| Bsc. | 8 (53.3%) | |

| DPT | 2 (13.3%) | |

| Master | 3 (20%) | |

| PhD | 2 (13.3%) | |

| Number of years working with people with stroke | 1–5 Years | 4 (26.7%) |

| 6–10 Years | 6 (40%) | |

| 11–15 Years | 3 (20%) | |

| ≤16 Years | 2 (13.3%) | |

| Theme | Subtheme |

|---|---|

| Theme 1: Organizational factors | Subtheme 1: Clinical context. Subtheme 2: Organizational culture. Subtheme 3: Organizational policies. |

| Theme 2: Individual clinician factors | Subtheme 1: Clinical experience and expertise. Subtheme 2: Skill, knowledge, and attitudes. |

| Theme 3: Patient factors. | Subtheme 1: Multimorbidity and comorbidities. Subtheme 2: Patient engagement and shared decision-making. |

| Theme 4: Other factors. | Subtheme 1: Research on RCT design. Subtheme 2: Stroke phases. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alatawi, S.F. Using Implementation Theories to Tailor International Clinical Guidelines for Post-Stroke Gait Disorders. Healthcare 2025, 13, 1794. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13151794

Alatawi SF. Using Implementation Theories to Tailor International Clinical Guidelines for Post-Stroke Gait Disorders. Healthcare. 2025; 13(15):1794. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13151794

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlatawi, Salem F. 2025. "Using Implementation Theories to Tailor International Clinical Guidelines for Post-Stroke Gait Disorders" Healthcare 13, no. 15: 1794. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13151794

APA StyleAlatawi, S. F. (2025). Using Implementation Theories to Tailor International Clinical Guidelines for Post-Stroke Gait Disorders. Healthcare, 13(15), 1794. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13151794