Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices Among Thoracic Healthcare Professionals Toward Postoperative Pulmonary Embolism

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Questionnaire

2.3. Sample Size Calculation

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the Participants

3.2. Knowledge

3.3. Attitudes

3.4. Practices

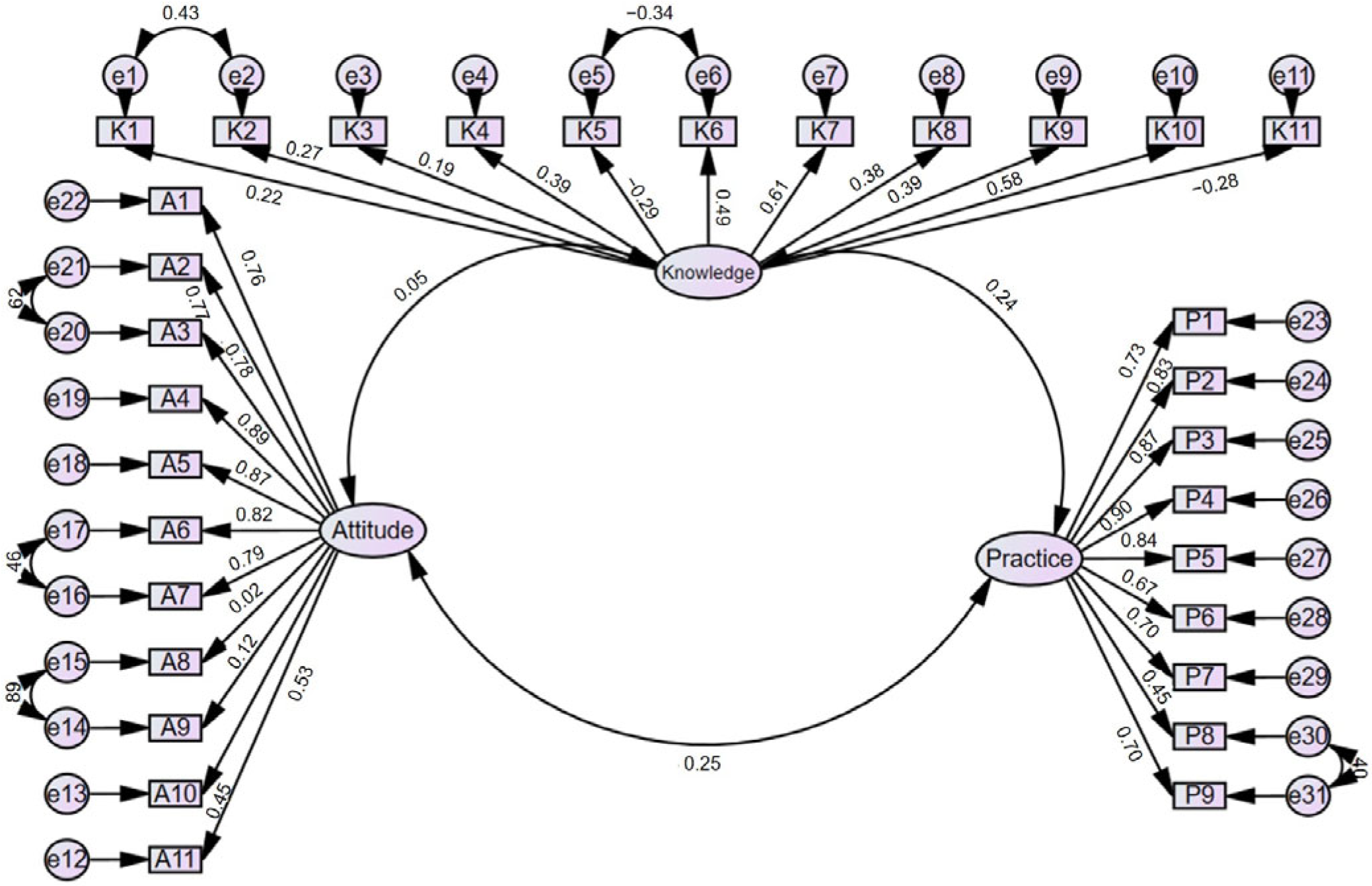

3.5. Correlation Analysis

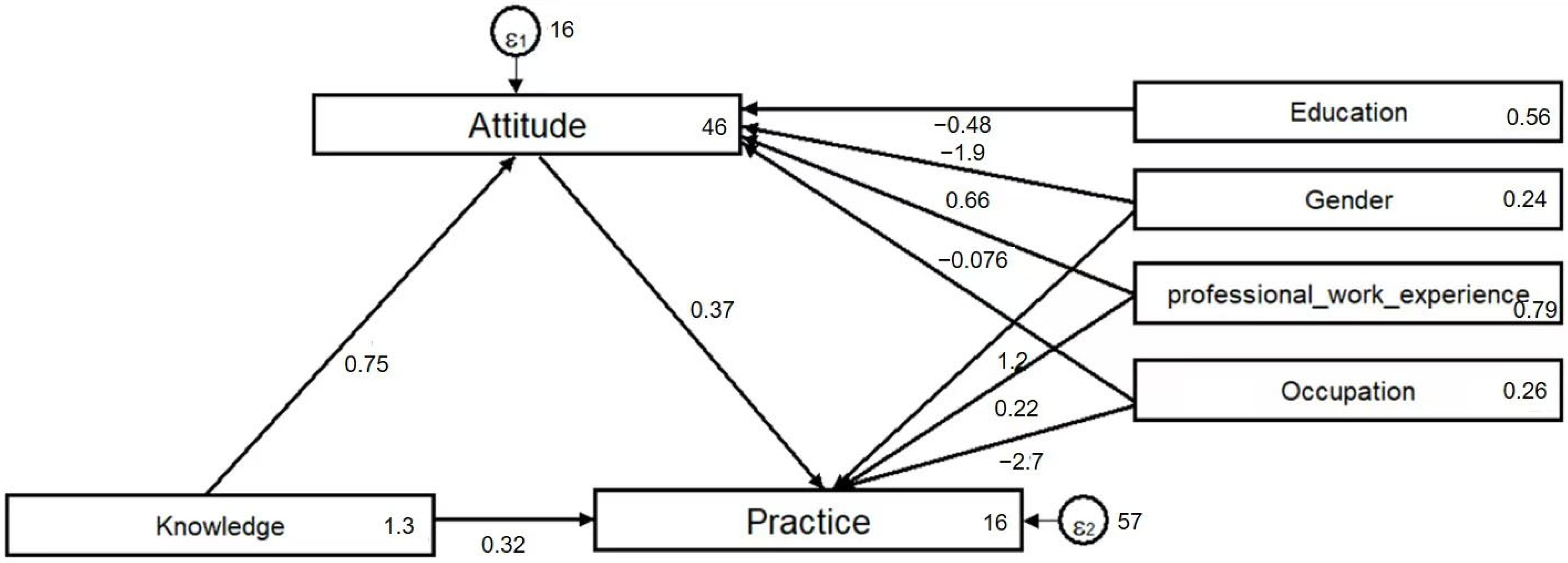

3.6. Path Analysis

3.7. Stratification Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Caron, A.; Depas, N.; Chazard, E.; Yelnik, C.; Jeanpierre, E.; Paris, C.; Beuscart, J.B.; Ficheur, G. Risk of Pulmonary Embolism More Than 6 Weeks After Surgery Among Cancer-Free Middle-aged Patients. JAMA Surg. 2019, 154, 1126–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Temgoua, M.N.; Tochie, J.N.; Noubiap, J.J.; Agbor, V.N.; Danwang, C.; Endomba, F.T.A.; Nkemngu, N.J. Global incidence and case fatality rate of pulmonary embolism following major surgery: A protocol for a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Syst. Rev. 2017, 6, 240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsuoka, Y.; Morimatsu, H. Incidence Rates of Postoperative Pulmonary Embolisms in Symptomatic and Asymptomatic Patients, Detected by Diagnostic Images—A Single-Center Retrospective Study. Circ. J. 2019, 83, 432–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haskins, I.N.; Rivas, L.; Ju, T.; Whitlock, A.E.; Amdur, R.L.; Sidawy, A.N.; Lin, P.P.; Vaziri, K. The association of IVC filter placement with the incidence of postoperative pulmonary embolism following laparoscopic bariatric surgery: An analysis of the Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery Accreditation and Quality Improvement Project. Surg. Obes. Relat. Dis. 2019, 15, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Liu, Z.; Chen, C.; Li, D.; Peng, H.; Zhao, P.; Wang, J. Risk factors and potential predictors of pulmonary embolism in cancer patients undergoing thoracic and abdominopelvic surgery: A case control study. Thromb. J. 2022, 20, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillegass, E.; Lukaszewicz, K.; Puthoff, M. Role of Physical Therapists in the Management of Individuals at Risk for or Diagnosed with Venous Thromboembolism: Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guideline 2022. Phys. Ther. 2022, 102, pzac057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brailovsky, Y.; Kunchakarra, S.; Lakhter, V.; Barnes, G.; Masic, D.; Mancl, E.; Porcaro, K.; Bechara, C.F.; Lopez, J.J.; Simpson, K.; et al. Pulmonary embolism response team implementation improves awareness and education among the house staff and faculty. J. Thromb. Thrombolysis 2020, 49, 54–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramjug, S.; Phillips, G. Update in the diagnosis and management of acute pulmonary embolism for the non-respiratory physician. Clin. Med. 2021, 21, e591–e597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shargall, Y.; Wiercioch, W.; Brunelli, A.; Murthy, S.; Hofstetter, W.; Lin, J.; Li, H.; Linkins, L.A.; Crowther, M.; Davis, R.; et al. Joint 2022 European Society of Thoracic Surgeons and The American Association for Thoracic Surgery guidelines for the prevention of cancer-associated venous thromboembolism in thoracic surgery. Eur. J. Cardio-Thorac. Surg. 2022, 63, ezac488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cochrane, B. Pleurisy and pulmonary embolism: Physician sees through patient eyes. Intern. Med. J. 2020, 50, 498–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hanawi, M.K.; Angawi, K.; Alshareef, N.; Qattan, A.M.N.; Helmy, H.Z.; Abudawood, Y.; Alqurashi, M.; Kattan, W.M.; Kadasah, N.A.; Chirwa, G.C.; et al. Knowledge, Attitude and Practice Toward COVID-19 Among the Public in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia: A Cross-Sectional Study. Front. Public Health 2020, 8, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsabaani, A.; Alqahtani, N.S.S.; Alqahtani, S.S.S.; Al-Lugbi, J.H.J.; Asiri, M.A.S.; Salem, S.E.E.; Alasmari, A.A.; Mahmood, S.E.; Alalyani, M. Incidence, Knowledge, Attitude and Practice Toward Needle Stick Injury Among Health Care Workers in Abha City, Saudi Arabia. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 771190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alabdullah, M.N.; Alabdullah, H.; Kamel, S. Knowledge, attitude, and practice of evidence-based medicine among resident physicians in hospitals of Syria: A cross-sectional study. BMC Med. Educ. 2022, 22, 785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boon, G.; Bogaard, H.J.; Klok, F.A. Essential aspects of the follow-up after acute pulmonary embolism: An illustrated review. Res. Pr. Thromb. Haemost. 2020, 4, 958–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Y.; Wang, W.; Zhen, K.; Zhao, J. Healthcare professionals’ knowledge, attitudes, and practices regarding graduated compression stockings: A survey of China’s big-data network. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2020, 20, 1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, X.; Xu, H.; Wang, Q.R. A rapid method to measure mouth breathing airflow volume. Int. J. Oral. Med. 2019, 46, 213–217. [Google Scholar]

- Catella, J.; Rivoire, E.; Abejiou, I.; Quiquandon, S.; Desmurs-Clavel, H.; Dargaud, Y. Age is a Risk Factor for Poor Knowledge About Venous Thromboembolism Treatment. Clin. Appl. Thromb. 2024, 30, 10760296241276527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, Z.; Jia, P.; Chen, J.; Su, Y.; Wang, L.; Zhang, Q.; Guo, D.Y. Research progress on knowledge-attitude-practice of VTE prevention in hospitalized patients: A review. Medicine 2024, 103, e38714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wu, X.J.; Ma, Y.F.; Xu, Y.; Wang, X.J.; Zhu, C.; Cao, J.; Jiao, J.; Liu, G.; Li, Z.; et al. Chinese orthopaedic nurses’ knowledge, attitude and venous thromboembolic prophylactic practices: A multicentric cross-sectional survey. J. Clin. Nurs. 2021, 30, 773–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walen, S.; Damoiseaux, R.A.; Uil, S.M.; van den Berg, J.W. Diagnostic delay of pulmonary embolism in primary and secondary care: A retrospective cohort study. Br. J. Gen. Pr. 2016, 66, e444–e450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almarshad, F.; Bandy, A.; Alfaiz, A.; Alotaibi, S.F.; Alaklabi, S.A.; Alotaibi, Y.F. A Multi-center Cross-Sectional Assessment of Healthcare Professionals’ Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices Toward Thromboprophylaxis. Cureus 2024, 16, e61835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Mugheed, K.; Bayraktar, N. Knowledge, risk assessment, practices, self-efficacy, attitudes, and behaviour’s towards venous thromboembolism among nurses: A systematic review. Nurs. Open 2023, 10, 6033–6044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, S.; Li, M.; Wang, K.; Hang, C.; Xu, D.; Jiang, Y.; Jia, Z. Knowledge, attitudes, and practices regarding venous thromboembolism prophylaxis: A survey of medical staff at a tertiary hospital in China. Medicine 2021, 100, e28016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gould, M.K.; Garcia, D.A.; Wren, S.M.; Karanicolas, P.J.; Arcelus, J.I.; Heit, J.A.; Samama, C.M. Prevention of VTE in nonorthopedic surgical patients: Antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest 2012, 141, e227S–e277S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caprini, J.A.; Tapson, V.F.; Hyers, T.M.; Waldo, A.L.; Wittkowsky, A.K.; Friedman, R.; Colgan, K.J.; Shillington, A.C.; Committee, N.S. Treatment of venous thromboembolism: Adherence to guidelines and impact of physician knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs. J. Vasc. Surg. 2005, 42, 726–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sathiapal, R.; Sivagnanaratnam, A. Reflecting on the importance of work experience for the next generation of doctors. Br. J. Hosp. Med. 2021, 82, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Necknig, U.H.; Wolff, I.; Brundl, J.; Kriegmair, M.C.; Marghawal, D.; Wagener, N.; Hegemann, M.; Eder, E.; Wulfing, C.; Burger, M.; et al. Impact of the experience of urological senior physicians in Germany on professional and personal aspects. Aktuelle Urol. 2022, 53, 331–342. [Google Scholar]

| Variables | N (%) | Knowledge Score | Attitude Score | Practices Score | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD | p | Mean ± SD | p | Mean ± SD | p | ||

| Total | 222 | 9.03 ± 1.13 | 50.09 ± 4.23 | 35.78 ± 7.85 | |||

| Gender | 0.281 | 0.003 * | 0.023 * | ||||

| Male | 95 (42.79) | 9.14 ± 1.02 | 51.06 ± 3.86 | 36.96 ± 8.12 | |||

| Female | 127 (57.21) | 8.94 ± 1.20 | 49.37 ± 4.36 | 34.90 ± 7.55 | |||

| Age | 0.26 | 0.061 | 0.138 | ||||

| <30 years | 85 (38.29) | 9.02 ± 0.91 | 49.28 ± 4.63 | 34.53 ± 8.07 | |||

| 30–40 years | 90 (40.54) | 8.91 ± 1.40 | 50.29 ± 4.00 | 36.11 ± 7.92 | |||

| >40 years | 47 (21.17) | 9.26 ± 0.87 | 51.19 ± 3.66 | 37.40 ± 7.06 | |||

| Years of professional work experience | 0.138 | 0.015 * | 0.006 * | ||||

| ≤5 years | 74 (33.33) | 8.99 ± 0.93 | 49.03 ± 4.88 | 35.24 ± 8.40 | |||

| 6–9 years | 42 (18.92) | 9.17 ± 1.06 | 50.69 ± 3.83 | 34.95 ± 7.24 | |||

| ≥10 years | 106 (47.75) | 9.00 ± 1.28 | 50.60 ± 3.76 | 36.48 ± 7.69 | |||

| Education | 0.674 | 0.049 * | 0.185 | ||||

| Junior college and bachelor’s degree | 137 (61.71) | 8.99 ± 1.20 | 49.66 ± 4.31 | 35.14 ± 7.70 | |||

| Master’s degree | 50 (22.52) | 9.16 ± 1.00 | 51.28 ± 4.06 | 36.86 ± 8.69 | |||

| Doctorate | 35 (15.77) | 8.97 ± 1.01 | 50.09 ± 3.94 | 36.74 ± 7.07 | |||

| Occupation | 0.207 | 0.004 | 0.005 | ||||

| Surgeons | 102 (45.95) | 9.14 ± 0.98 | 50.95 ± 3.94 | 37.19 ± 7.96 | |||

| Nurses | 120 (54.05) | 8.92 ± 1.23 | 49.36 ± 4.34 | 34.57 ± 7.57 | |||

| Professional title | 0.333 | 0.111 | 0.197 | ||||

| Primary | 94 (42.34) | 9.01 ± 1.02 | 49.77 ± 4.42 | 34.98 ± 8.24 | |||

| Middle | 86 (38.74) | 8.92 ± 1.34 | 49.76 ± 4.40 | 35.78 ± 7.94 | |||

| Vice-senior | 25 (11.26) | 9.28 ± 0.54 | 52.00 ± 2.74 | 36.16 ± 6.82 | |||

| Senior | 17 (7.66) | 9.29 ± 1.16 | 50.82 ± 3.41 | 39.65 ± 5.62 | |||

| Hospital level | 0.137 | 0.088 | 0.768 | ||||

| Primary | 6 (2.70) | 8.33 ± 0.82 | 46.50 ± 3.51 | 34.17 ± 8.66 | |||

| Secondary | 15 (6.76) | 9.20 ± 0.56 | 50.40 ± 4.67 | 35.13 ± 8.02 | |||

| Tertiary | 201 (90.54) | 9.03 ± 1.16 | 50.18 ± 4.19 | 35.88 ± 7.85 | |||

| Correctness N (%) | |

|---|---|

| K1. Pulmonary embolism encompasses a spectrum of conditions resulting from the occlusion of the pulmonary arterial system by emboli of diverse origins. It constitutes a significant postoperative complication in the realm of thoracic surgery. | 219 (98.65) |

| K2. Chest trauma is a known factor contributing substantially to the heightened incidence of pulmonary embolism. This association may be attributed to the impeding of pulmonary circulation and concurrent lung tissue injury. | 216 (97.3) |

| K3. Pulmonary embolism exhibits subtle clinical manifestations, a propensity for misdiagnosis, and alarmingly high mortality rates, warranting vigilant attention. | 218 (98.2) |

| K4. Predisposing risk factors for post-thoracic surgery pulmonary embolism typically comprise advanced age, a history of smoking, obesity, trauma, and thoracic malignancies. | 219 (98.65) |

| K5. The characteristic clinical presentations of pulmonary embolism, which typically manifest concomitantly, constitute the “pulmonary embolism triad,” encompassing dyspnea, chest pain, hemoptysis, and/or circulatory failure. | 55 (24.77) |

| K6. Bedside color Doppler echocardiography, lower extremity vascular ultrasonography, and transesophageal echocardiography are often employed as the primary diagnostic modalities for pulmonary embolism. | 167 (75.23) |

| K7. Spiral CT pulmonary angiography stands as a reliable method for guiding thrombolytic therapy and evaluating its therapeutic efficacy. | 200 (90.09) |

| K8. Postoperative preventative measures encompass early mobilization, intermittent sequential compression to enhance lower limb blood circulation, and pharmaceutical prophylaxis, such as unfractionated heparin, low-molecular-weight heparin, and warfarin. | 216 (97.3) |

| K9. Given the absence of anticoagulation contraindications, heparin anticoagulation represents the primary treatment modality for post-thoracic surgery pulmonary embolism. | 204 (91.89) |

| K10. Interventional strategies for managing pulmonary embolism following thoracic surgery frequently entail a combination of mechanical thrombectomy, thrombectomy, and localized thrombolysis. | 188 (84.68) |

| K11. Surgical intervention typically involves pulmonary artery thrombectomy, with early postoperative recovery demonstrating limited associations with overall prognosis. | 102 (45.95) |

| Strongly Agree N (%) | Agree N (%) | Neutral N (%) | Disagree N (%) | Strongly Disagree N (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1. It is crucial for medical professionals in thoracic surgery to undergo training pertaining to the prevention and treatment of pulmonary embolism, as it directly impacts the execution of clinical responsibilities and patient prognosis. (P) | 206 (92.79) | 15 (6.76) | 1 (0.45) | / | / |

| A2. You are open to discussing the challenges encountered during the clinical practice of pulmonary embolism following thoracic surgery with fellow healthcare practitioners and actively seeking viable solutions. (P) | 195 (87.84) | 26 (11.71) | 1 (0.45) | / | / |

| A3. You are committed to acquiring expert consensus on pulmonary embolism following thoracic surgery, updating relevant knowledge, and enhancing the standard of care in preventing and treating pulmonary embolism. (P) | 195 (87.84) | 26 (11.71) | 1 (0.45) | / | / |

| A4. Recognizing the latent and deleterious nature of pulmonary embolism symptoms post-thoracic surgery, it is imperative to assess the risk of pulmonary embolism in patients during the perioperative phase to ensure their well-being. (P) | 197 (88.74) | 22 (9.91) | 3 (1.35) | / | / |

| A5. Proficiency in diverse treatment options for pulmonary embolism is of paramount importance for the prognosis of thoracic surgery patients, emphasizing the significance of medical staff in this specialty. (P) | 192 (86.49) | 26 (11.71) | 4 (1.8) | / | / |

| A6. You acknowledge the significance of preoperative assessment for identifying risk factors related to pulmonary embolism in patients. (P) | 192 (86.49) | 28 (12.61) | 2 (0.9) | / | / |

| A7. Early intervention in cases of pulmonary embolism is a pivotal factor in safeguarding the prognosis and quality of life for patients. (P) | 189 (85.14) | 32 (14.41) | 1 (0.45) | / | / |

| A8. You are cautious about anticoagulant interventions due to the potential risk of bleeding when using heparin and other medications to prevent and treat pulmonary embolism post-thoracic surgery. (N) | 60 (27.03) | 63 (28.38) | 38 (17.12) | 10 (4.5) | 51 (22.97) |

| A9. Balancing the costs associated with various preventative and control measures for pulmonary embolism after thoracic surgery, you are somewhat reluctant to implement these interventions. (N) | 48 (21.62) | 11 (4.95) | 18 (8.11) | 70 (31.53) | 75 (33.78) |

| A10. You recognize the necessity of perfecting preoperative color Doppler ultrasound examinations for both lower extremities. (P) | 150 (67.57) | 56 (25.23) | 9 (4.05) | 5 (2.25) | 2 (0.9) |

| A11. You have placed significant emphasis on monitoring D-dimer levels in the coagulation profile. (P) | 156 (70.27) | 50 (22.52) | 12 (5.41) | 3 (1.35) | 1 (0.45) |

| Very Consistent N (%) | Somewhat Consistent N (%) | Neutral N (%) | Somewhat Inconsistent N (%) | Very Inconsistent N (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1. How frequently do you actively acquire knowledge pertaining to the prevention and treatment of pulmonary embolism following thoracic surgery through various means, such as engaging in training, reviewing medical literature or expert consensus, and engaging in discussions with fellow medical professionals? (P) | 68 (30.63) | 42 (18.92) | 76 (34.23) | 34 (15.32) | 2 (0.9) |

| P2. How often do you evaluate or document risk factors or indications of pulmonary embolism in patients following thoracic surgery prior to the surgical procedure? (P) | 81 (36.49) | 50 (22.52) | 50 (22.52) | 37 (16.67) | 4 (1.8) |

| P3. Throughout the course of thoracic surgery, do you conscientiously monitor variables including surgical duration, hematoma compression, and other intraoperative factors, and integrate them into your subsequent practices for the prevention and treatment of pulmonary embolism in patients? (P) | 85 (38.29) | 55 (24.77) | 47 (21.17) | 26 (11.71) | 9 (4.05) |

| P4. While performing thoracic surgery, it is essential to maintain a heightened awareness of high-risk factors associated with pulmonary embolism linked to anesthesia, such as limb hypoperfusion and reduced venous blood flow, and incorporate these considerations into your preventative and treatment measures for embolization. (P) | 85 (38.29) | 54 (24.32) | 47 (21.17) | 26 (11.71) | 10 (4.5) |

| P5. How closely do you monitor the frequency of symptoms related to pulmonary embolism, such as the pulmonary embolism triad, in post-surgery patients? (P) | 100 (45.05) | 61 (27.48) | 41 (18.47) | 17 (7.66) | 3 (1.35) |

| P6. What is the frequency of your clinical engagement in preventative and treatment practices for pulmonary embolism using medications like heparin and warfarin for patients? (P) | 115 (51.8) | 50 (22.52) | 35 (15.77) | 16 (7.21) | 6 (2.7) |

| P7. Have you employed techniques such as color Doppler echocardiography and lower limb vascular ultrasonography, as well as other imaging methods, to detect the occurrence of venous thrombosis in patients? (P) | 92 (41.44) | 55 (24.77) | 41 (18.47) | 17 (7.66) | 17 (7.66) |

| P8. How frequently do you recommend or assist patients in post-surgery activities such as mobilization, local limb massage, regular repositioning, and elevation of the lower limbs as part of pulmonary embolism prevention and treatment? (P) | 161 (72.52) | 36 (16.22) | 15 (6.76) | 7 (3.15) | 3 (1.35) |

| P9. Summarize your experience in the prevention and treatment of pulmonary embolism, encompassing preoperative assessment, intraoperative vigilance, and postoperative care. Apply this experience to enhance the frequency of pulmonary embolism prevention and treatment following thoracic surgery in the future. (P) | 115 (51.8) | 53 (23.87) | 35 (15.77) | 15 (6.76) | 4 (1.8) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ma, Y.; Xing, X.; Li, S.; Li, J.; Ma, Z.; Sun, L.; Zhang, D.; Kong, R. Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices Among Thoracic Healthcare Professionals Toward Postoperative Pulmonary Embolism. Healthcare 2025, 13, 1771. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13151771

Ma Y, Xing X, Li S, Li J, Ma Z, Sun L, Zhang D, Kong R. Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices Among Thoracic Healthcare Professionals Toward Postoperative Pulmonary Embolism. Healthcare. 2025; 13(15):1771. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13151771

Chicago/Turabian StyleMa, Yuefeng, Xin Xing, Shaomin Li, Jianzhong Li, Zhenchuan Ma, Liangzhang Sun, Danjie Zhang, and Ranran Kong. 2025. "Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices Among Thoracic Healthcare Professionals Toward Postoperative Pulmonary Embolism" Healthcare 13, no. 15: 1771. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13151771

APA StyleMa, Y., Xing, X., Li, S., Li, J., Ma, Z., Sun, L., Zhang, D., & Kong, R. (2025). Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices Among Thoracic Healthcare Professionals Toward Postoperative Pulmonary Embolism. Healthcare, 13(15), 1771. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13151771