Transforming Palliative Care for Rural Patients with COPD Through Nurse-Led Models

Abstract

1. Introduction

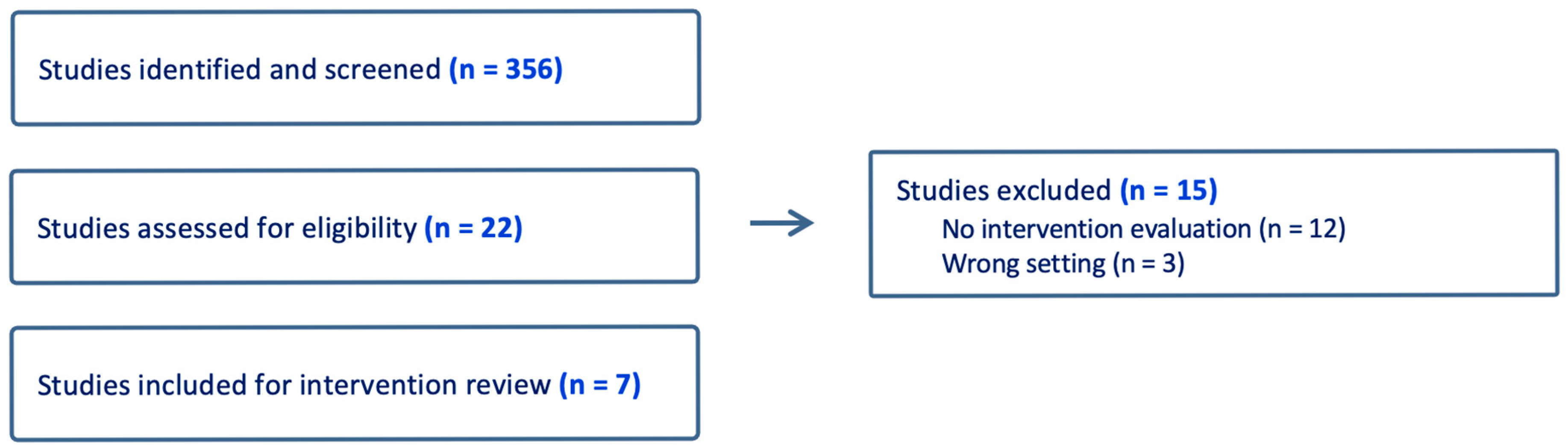

Methodological Approach

2. Nurse-Led Palliative Care Interventions for Patients with COPD

2.1. Rural Disparities in COPD Care

2.2. Nurse-Led Interventions in Rural Settings for Palliative Care Patients with COPD

2.3. Home-Based Care Models

2.4. Telehealth

2.5. Community Health Programs/Outreach

2.6. Primary Care in Rural Communities

2.7. Nurse-Led Interventions for Advance Care Planning and Cost Effectiveness

2.8. Integrating Rural Palliative Care into Nursing Training

3. Case Examples

3.1. Embedded RN in Primary Care

- Discussion:

3.2. Telehealth-Delivered Nurse Practitioner Palliative Support

- Discussion:

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

Future Research Directions

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Iyer, A.S.; Sullivan, D.R.; Lindell, K.O.; Reinke, L.F. The Role of Palliative Care in COPD. Chest 2022, 161, 1250–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raju, S.; Brigham, E.P.; Paulin, L.M.; Putcha, N.; Balasubramanian, A.; Hansel, N.H.; McCormack, M.C. The Burden of Rural Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: Analyses from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2020, 201, 488–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picazo, F.; Duan, K.I.; Wai, T.H.; Hayes, S.; Leonhard, A.G.; Fonseca, G.A.; Plumley, R.; Beaver, K.A.; Donovan, L.M.; Au, D.H.; et al. Rural Residence Associated with Receipt of Recommended Postdischarge Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Care among a Cohort of U.S. Veterans. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2025, 22, 515–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, S.; Higgins, E.; Cain, J.; Coyne, P.; Peacock, R.; Logan, A.; Fasolino, T.; Lindell, K. Dyspnea and Palliative Care in Advanced COPD: A Rapid Review. J. Hosp. Palliat. Nurs. 2024, 26, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, S. Caring for the Chronically Ill Patient: Understanding How Fear Leads to Activity Avoidance in Individuals with Chronic Respiratory Disease. Int. J. Nurs. 2014, 3, 11–16. [Google Scholar]

- Leupoldt, A.v.; Janssens, T. Could targeting disease-specific fear and anxiety improve COPD outcomes? Expert. Rev. Respir. Med. 2016, 10, 835–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, M.; Decramer, M.; O’Donnell, D.E. No room to breath: The importance of lung hyperinflation in COPD. Prim. Care Respir. J. 2013, 22, 101–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pooler, A.; Beech, R. Examining the relationship between anxiety and depression and exacerbations of COPD which result in hospital admission: A systematic review. Int. J. Chron. Obs. Pulmon Dis. 2014, 9, 315–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrell, B.R.; Twaddle, M.L.; Melnick, A.; Meier, D.E. National Consensus Project Clinical Practice Guidelines for Quality Palliative Care Guidelines. J. Palliat. Med. 2018, 21, 1684–1689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, D.; Iyer, A.S.; Enguidanos, S.; Cox, C.E.; Farquhar, M.; Janssen, D.J.; Lindell, K.; Mularski, R.A.; Smallwood, N.; Turnbull, A.E.; et al. Palliative Care Early in the Care Continuum among Patients with Serious Respiratory Illness: An Official ATS/AAHPM/HPNA/SWHPN Policy Statement. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2022, 206, 672–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temel, J.S.; Greer, A.; Muzikansky, A.; Admane, S.; Jackson, V.A.; Dahlin, C.M.; Blinderman, C.D.; Jacobsen, J.; Pirl, W.F.; Billings, J.A.; et al. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010, 363, 733–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pascoe, A.; Buchan, C.; Smallwood, N. Provision of palliative care for people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: A narrative review. Ann. Palliat. Med. 2024, 13, 1012027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madiraca, J.; Lindell, K.; Phillips, S.; Coyne, P.; Miller, S. Palliative Care Needs of Women With Advanced Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: A Mixed Methods Study. J. Hosp. Palliat. Nurs. 2024, 26, E154–E162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suen, A.O.; Bischoff, K.; Iyer, A.S.; Radhakrishnan, K.; Fenton, C.; Singer, J.P.; Sudore, R.L.; Kotwal, A.; Farrand, E. Differences in Healthcare and Palliative Care Utilization at the End of Life: A Comparison Study Between Lung Cancer. COPD, and IPF. Chest 2024, 166, 1487–1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindell, K.; Madisetti, M.; Pittman, M.C.; Fasolino, T.; Whelan, T.; Mueller, M.; Ford, D.W. Pulmonologists’ Perspectives on and Access to Palliative Care for Patients with Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis in South Carolina. Palliat. Med. Rep. 2023, 4, 292–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulto, L.N. The role of nurse-led telehealth interventions in bridging healthcare gaps and expanding access. Nurs. Open 2024, 11, e2092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesut, B.; Hooper, B.; Jacobsen, M.; Nielsen, B.; Falk, M.; O ‘Connor, B.P. Nurse-led navigation to provide early palliative care in rural areas: A pilot study. BMC Palliat. Care 2017, 16, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyer, A.; Dionne-Odom, J.N.; Ford, S.M.; Crump Tims, S.L.; Sockwell, E.D.; Ivankova, N.V.; Brown, C.J.; Tucker, R.O.; Dransfield, M.T.; Bakitas, M.A. A Formative Evaluation of Patient and Family Caregiver Perspectives on Early Palliative Care in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease across Disease Severity. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2019, 16, 1024–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byun, J.Y.; Bechthold, A.C.; Coffee-Dunning, J.; Armstrong, M.; Taylor, R.; O’Hare, L.; Dransfield, M.T.; Brown, C.J.; Vance, D.E.; Odom, J.N.; et al. Project EPIC (Empowering People to Independence in COPD): Study protocol for a hybrid effectiveness-implementation pilot randomized controlled trial of telephonic. geriatrics-palliative care nurse-coaching in older adults with COPD and their family caregivers. Contemp. Clin. Trials 2024, 140, 107487. [Google Scholar]

- Moy, M.L.; Collins, R.J.; Martinez, C.H.; Kadri, R.; Roman, P.; Holleman, R.G.; Kim, H.M.; Nguyen, H.Q.; Cohen, M.D.; Goodrich, D.E.; et al. An Internet-Mediated Pedometer-Based Program Improves Health-Related Quality-of-Life Domains and Daily Step Counts in COPD: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Chest 2015, 148, 128–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ora, L.; Wilkes, L.; Mannix, J.; Gregory, L.; Luck, L. Embedding nurse-led supportive care in an outpatient service for patients with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. J. Adv. Nurs. 2023, 79, 3274–3285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houben, C.H.M.; Spruit, M.A.; Luyten, H.; Pennings, H.J.; van den Boogart, V.E.M.; Creemers, J.P.H.M.; Wesseling, G.; Wouters, E.F.M.; Janssen, D.J.A. Cluster-randomised trial of a nurse-led advance care planning session in patients with COPD and their loved ones. Thorax 2019, 74, 328–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gloeckl, R.; Heinzelmann, I.; Matthaei, M.; Seeberg, S.; Damisch, T.; Jerrentrup, A.; Kenn, K. Benefits of an oxygen reservoir cannula versus a conventional nasal cannula during exercise in hypoxemic COPD patients: A crossover trial. Respiration 2014, 88, 399–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.; Devoti, A.; O’Connor, M. Rural and urban disparities in quality of home health care: A longitudinal cohort study (2014–2018). J. Rural. Health 2022, 38, 705–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raju, S.; Keet, C.A.; Paulin, L.M.; Matsui, E.C.; Peng, R.D.; Hansel, N.N.; McCormack, M.C. Rural Residence and Poverty Are Independent Risk Factors for Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease in the United States. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2019, 199, 961–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Dijk, C.E.; Garcia-Aymerich, J.; Carsin, A.-E.; Smit, L.A.M.; Borlée, F.; Heederik, D.J.; Donker, G.A.; Yzermans, C.J.; Zock, J.P. Risk of exacerbations in COPD and asthma patients living in the neighbourhood of livestock farms: Observational study using longitudinal data. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 2016, 219, 278–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croft, J.B.; Wheaton, A.G.; Liu, Y.; Xu, F.; Lu, H.; Matthews, K.A.; Cunningham, T.J.; Wang, Y.; Holt, J.B. Urban-Rural County and State Differences in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease—United States. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2015, 67, 205–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, C.S. Kotwalk. A.A. Loneliness and Social Isolation in Palliative Care: A Call to Action. J. Palliat. Med. 2023, 26, 1032–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindell, K.; Klein, S.J.; Veatch, M.S.; Gibson, K.F.; Kass, D.J.; Nouraie, M.; Rosenzweig, M.Q. Nurse-Led Palliative Care Improves Knowledge and Preparedness in Caregivers of Patients with Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2021, 18, 1811–1821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ora, L.; Mannix, J.; Morgan, L.; Wilkes, L. Nurse-led integration of palliative care for chronic obstructive pulmonar disease: An integrative literature review. J. Clin. Nurs. 2019, 28, 3725–3733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madiraca, J.; Lindell, K.; Coyne, P.; Miller, S. Palliative Care Interventions in Advanced Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: An Integrative Review. J. Palliat. Med. 2023, 26, 856–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, S.N.; Nichols, M.; Teufel, R.J., II; Silverman, E.; Walentynowicz, M. Use of Ecological Momentary Assessment to Measure Dyspnea in COPD. Int. J. Chronic Obs. Pulm. Dis. 2024, 19, 841–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghazal, K.Y.; Singh Beniwal, S.; Dhingra, A. Assessing Telehealth in Palliative Care: A Systematic Review of the Effectiveness and Challenges in Rural and Underserved Areas. Cureus 2024, 16, e68275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couchman, E.; Leach, I.; Bayly, J.; Gardiner, C.; Sleeman, K.E.; Evans, C.J. Integration of primary care and palliative care services to improve equality and equity at the end-of-life: Findings from realist stakeholder workshops. Palliat. Med. 2024, 38, 830–841. [Google Scholar]

- Kavalieratos, D.; Corbelli, J.; Zhang, D.; Dionne-Odom, J.N.; Ernecoff, N.C.; Hanmer, J.; Hoydich, Z.P.; Ikejiani, D.Z.; Klein-Fedyshin, M.; Zimmermann, C.; et al. Association Between Palliative Care and Patient and Caregiver Outcomes: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA 2016, 316, 2104–2114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melani, A.S. Inhaler technique in asthma and COPD: Challenges and unmet knowledge that can contribute to suboptimal use in real life. Expert. Rev. Clin. Pharmacol. 2021, 14, 991–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collins, P.F.; Stratton, R.J.; Elia, M. Nutritional support in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2012, 95, 1385–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease 2024 GOLD Report. 2024. Available online: https://goldcopd.org/2024-gold-report/ (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- Portable Oxygen Delivery and Oxygen Conserving Devices. Available online: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/portable-oxygen-delivery-and-oxygen-conserving-devices (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; National Academy of Medicine; Committee on the Future of Nursing 2020–2030. The Future of Nursing 2020–2030: Charting a Path to Achieve Health Equity; Flaubert, J.L., Le Menestrel, S., Williams, D.R., Wakefield, M.K., Eds.; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- AACN. The Essentials: Core Competencies for Professional Nursing Education. 2021. Available online: https://www.aacnnursing.org/Portals/42/AcademicNursing/pdf/Essentials-2021.pdf (accessed on 6 May 2025).

- Kavanagh, J.M.; Sharpnack, P.A. Crisis in Competency: A Defining Moment in Nursing Education. Online J. Issues Nurs. 2021, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AANP. State Practice Environment. Available online: https://www.aanp.org/advocacy/state/state-practice-environment (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- Lippe, M.; Davis, A.; Stock, N.; Mazanec, P.; Ferrell, B. Updated palliative care competencies for entry-to-practice and advanced-level nursing students: New resources for nursing faculty. J. Prof. Nurs. 2022, 42, 251–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poston, K.; Brunette, G.; Ciccone, J. Collaborative strategies to improve clinical judgement and address bedside care challenges. Teach. Learn. Nurs. 2023, 18, e94–e97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowell, V.L.; Yan, W. Applying Systems Thinking for Designing Immersive Virtual Reality Learning Experiences in Education. TechTrends 2024, 68, 149–160. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrell, B.; Mazanec, P.; Malloy, P.; Virani, R. An Innovative End-of-Life Nursing Education Consortium Curriculum That Prepares Nursing Students to Provide Primary Palliative Care. Nurse Educ. 2018, 43, 242–246. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gillespie, G.L.; Farra, S.; Regan, S.L.; Brammer, S.V. Impact of immersive virtual reality simulations for changing knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors. Nurse Educ. Today 2021, 105, 105025. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mazanec, P.; Ferrell, B.; Virani, R.; Alayu, J.; Ruel, N.H. Preparing New Graduate RNs to Provide Primary Palliative Care. J. Contin. Educ. Nurs. 2020, 51, 280–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, L.; Emerson, K. An Innovative Academic-Practice Partnership Using Simulation to Provide End-of-Life Education for Undergraduate Nursing Students in Rural Settings. Nurs. Educ. Perspect. 2024, 45, 126–128. [Google Scholar]

| Author (Yr) | Intervention Type | Care Delivery Modality | Patient Population | Palliative Care Outcomes | Considerations for Nursing |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pesut et al. (2017) [17] | Nurse-led home-based palliative care pilot study | In-person, home visits biweekly | Older adults with advanced chronic illness (n = 25) and family members in rural communities (n = 11) | High patient and family satisfaction, minimal emergency room use, many patients died in preferred location when indicated. | Nurse navigators in rural settings can facilitate early palliative care for COPD. Nurses can provide symptom management, education, advance care planning, advocacy, and psychosocial support. |

| Iyer et al. (2019) [18] Byun et al. (2024) [19] | Nurse-led telehealth palliative care for COPD | Telehealth (video and remote monitoring) | Patients with COPD and their caregivers (n = 60 dyads) | Formative evaluation (Iyer, 2019 [18]) found early PC acceptable, prioritizing coping, symptoms, prognostic awareness, and illness understanding. | Nurses can do real-time assessment, education focused on priority areas, and symptom management and facilitate advance care planning for patients and caregivers. |

| Moy et al. (2015) [20] | Internet-mediated, mobile health walking program | Mobile health and online platform | Veterans with COPD (n = 239) | Increased daily step counts, improved health-related quality of life. | Nurses can educate patients and facilitate remote, tech-supported exercise programs and foster peer support. |

| Ora et al. (2023) [21] | Embedded nurse-led supportive care within outpatient COPD service | Outpatient and primary care setting | Patients with COPD in Australia (rural-focused service), semi-structured interviews with healthcare professional (n = 6) | Improved relationships, trust, and collaboration between respiratory and palliative care teams. Benefits for patients, including improved supportive care. | Nurses with clinical expertise can lead models of care that address unmet biopsychosocial and spiritual needs of patients with COPD. |

| Houben et al. (2019) [22] | A nurse-led structured advance care planning (ACP) session | In-person ACP discussions | Patients with COPD (n = 165) | One 1.5 h structured, nurse-led ACP intervention improved quality of end-of-life communication and reduced anxiety among loved ones. | Nurses can initiate and guide ACP discussions, improving patient autonomy and preparedness, and support emotional well-being in patients and loved ones. |

| Gloeckl et al. (2014) [23] | Oxygen-conserving nasal cannula use during pulmonary rehabilitation | Pulmonary rehabilitation | Patients with severe COPD (n = 43) | Superior oxygen delivery, improved mobility and exercise tolerance. | Nurses can initiate oxygen-conserving device therapy, monitor patient oxygen levels, and provide education. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Poston, K.; Nasti, A.; Cormack, C.; Miller, S.N.; Lindell, K.O. Transforming Palliative Care for Rural Patients with COPD Through Nurse-Led Models. Healthcare 2025, 13, 1687. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13141687

Poston K, Nasti A, Cormack C, Miller SN, Lindell KO. Transforming Palliative Care for Rural Patients with COPD Through Nurse-Led Models. Healthcare. 2025; 13(14):1687. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13141687

Chicago/Turabian StylePoston, Kristen, Alexa Nasti, Carrie Cormack, Sarah N. Miller, and Kathleen Oare Lindell. 2025. "Transforming Palliative Care for Rural Patients with COPD Through Nurse-Led Models" Healthcare 13, no. 14: 1687. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13141687

APA StylePoston, K., Nasti, A., Cormack, C., Miller, S. N., & Lindell, K. O. (2025). Transforming Palliative Care for Rural Patients with COPD Through Nurse-Led Models. Healthcare, 13(14), 1687. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13141687