Development and Feasibility of a Smartphone Application for Promoting Healthy Heart Behaviors Following Open-Heart Surgery: A Mixed-Method Pilot Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

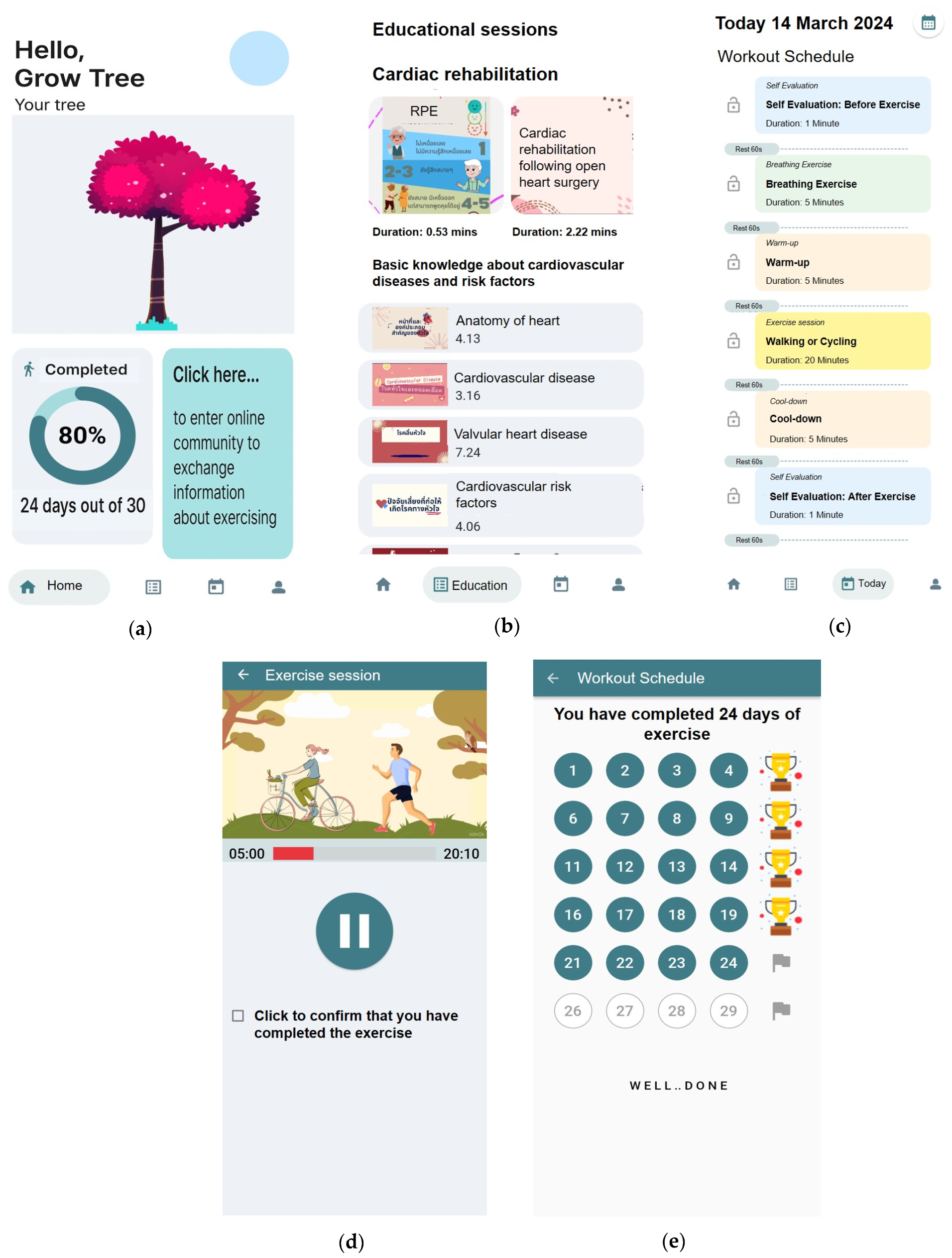

2.2. Application Design

2.3. Application Development Process

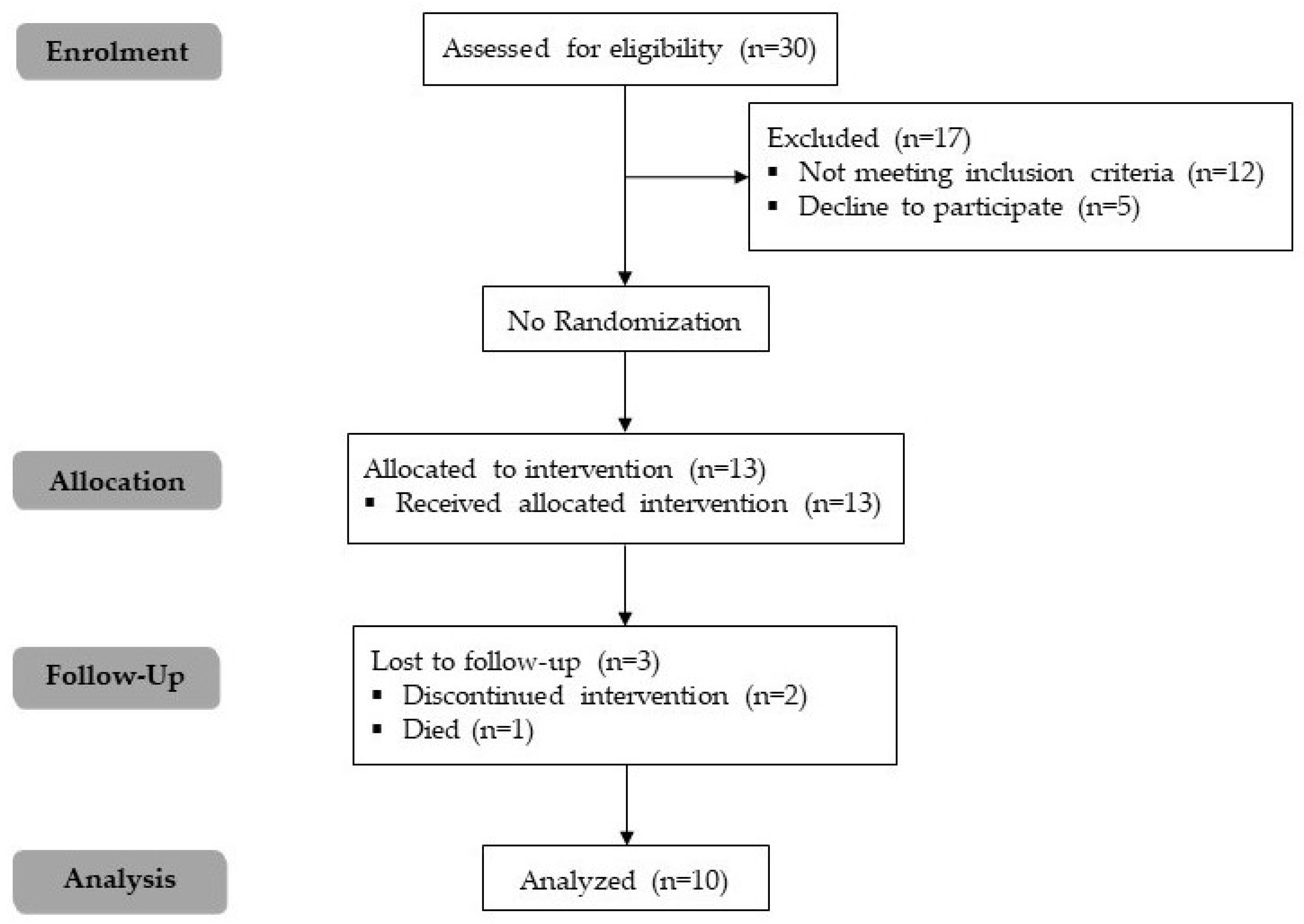

2.4. Participants

2.5. Feasibility, Data Collection, and Outcome Measures

2.6. Data Analysis

2.6.1. Quantitative Data

2.6.2. Qualitative Data

3. Results

3.1. Development of the Smartphone App

3.2. Baseline Characteristics of Participants

3.3. Quantitative Findings

3.3.1. Application Engagement

3.3.2. Application Usability

3.3.3. Application User Satisfaction

3.3.4. Healthy Behaviors Improvement

3.4. Qualitative Findings

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. The Top 10 Causes of Death. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/the-top-10-causes-of-death (accessed on 4 March 2022).

- Office of the Permanent Secretary Ministry of Public Health. Public Health Statistics A.D. 2021; Ministry of Public Health: Nonthaburi, Thailand, 2021.

- Lawton, J.S.; Tamis-Holland, J.E.; Bangalore, S.; Bates, E.R.; Beckie, T.M.; Bischoff, J.M.; Bittl, J.A.; Cohen, M.G.; DiMaio, J.M.; Don Creighton, W.; et al. 2021 ACC/AHA/SCAI Guideline for Coronary Artery Revascularization. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2022, 79, e21–e129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghisi, G.L.d.M.; Chaves, G.S.d.S.; Bennett, A.; Lavie, C.J.; Grace, S.L. The Effects of Cardiac Rehabilitation on Mortality and Morbidity in Women: A Meta-Analysis Attempt. J. Cardiopulm. Rehabil. Prev. 2019, 39, 39–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graham, H.L.; Lac, A.; Lee, H.; Benton, M.J. Predicting Long-Term Mortality, Morbidity, and Survival Outcomes Following a Cardiac Event: A Cardiac Rehabilitation Study. Rehabil. Process Outcome 2019, 8, 1179572719827610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medina-Inojosa, J.R.; Grace, S.L.; Supervia, M.; Stokin, G.; Bonikowske, A.R.; Thomas, R.; Lopez-Jimenez, F. Dose of Cardiac Rehabilitation to Reduce Mortality and Morbidity: A Population-Based Study. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2021, 10, e021356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raungratanaamporn, S.; Yunibhand, J.; Jitpanya, C. Factors predicting physical activity after hospitalization among new coronary artery disease patients. J. Health Res. 2015, 29, 127–133. [Google Scholar]

- Kotcharoen, R.; Tower, M.; Boyde, M.; Eley, R. Facilitators and Barriers to Cardiac Rehabilitation Uptake Among Patients with Coronary Artery Disease in Thailand: A Qualitative Study. ASEAN J. Rehabil. Med. 2024, 34, 85–95. [Google Scholar]

- Ragupathi, L.; Stribling, J.; Yakunina, Y.; Fuster, V.; McLaughlin, M.A.; Vedanthan, R. Availability, Use, and Barriers to Cardiac Rehabilitation in LMIC. Glob. Heart 2017, 12, 323–334.e310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsen, W.; Kumar, S.; Shar, A.; Varoquiers, C.; Wiley, T.; Riley, W.T.; Pavel, M.; Atienza, A.A. Advancing the science of mHealth. J. Health Commun. 2012, 17, 5–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz-Ramos, N.A.; Alor-Hernández, G.; Colombo-Mendoza, L.O.; Sánchez-Cervantes, J.L.; Rodríguez-Mazahua, L.; Guarneros-Nolasco, L.R. mHealth Apps for Self-Management of Cardiovascular Diseases: A Scoping Review. Healthcare 2022, 10, 322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forman, D.E.; LaFond, K.; Panch, T.; Allsup, K.; Manning, K.; Sattelmair, J. Utility and efficacy of a smartphone application to enhance the learning and behavior goals of traditional cardiac rehabilitation: A feasibility study. J. Cardiopulm. Rehabil. Prev. 2014, 34, 327–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lunde, P.; Bye, A.; Bergland, A.; Grimsmo, J.; Jarstad, E.; Nilsson, B.B. Long-term follow-up with a smartphone application improves exercise capacity post cardiac rehabilitation: A randomized controlled trial. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2020, 27, 1782–1792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venkatraman, V.; Lad, S.P.; Gellad, Z.F.; Heo, H.; Wu, K.A.; Dharmapurikar, R.; Liu, B.; Jung, S.H.; Plichta, R.; Harrison, J.K.; et al. Improving patient outcomes with a mobile digital health platform for patients undergoing transcatheter aortic valve replacement. J. Invasive Cardiol. 2023, 35, 10–25270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernal-Jiménez, M.; Calle, G.; Gutiérrez Barrios, A.; Gheorghe, L.L.; Cruz-Cobo, C.; Trujillo-Garrido, N.; Rodríguez-Martín, A.; Tur, J.A.; Vázquez-García, R.; Santi-Cano, M.J. Effectiveness of an Interactive mHealth App (EVITE) in Improving Lifestyle After a Coronary Event: Randomized Controlled Trial. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2024, 12, e48756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brørs, G.; Pettersen, T.R.; Hansen, T.B.; Fridlund, B.; Hølvold, L.B.; Lund, H.; Norekvål, T.M. Modes of e-Health delivery in secondary prevention programmes for patients with coronary artery disease: A systematic review. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2019, 19, 364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boszko, M.; Krzowski, B.; Peller, M.; Hoffman, P.; Żurawska, N.; Skoczylas, K.; Osak, G.; Kołtowski, Ł.; Grabowski, M.; Opolski, G.; et al. Impact of AfterAMI Mobile App on Quality of Life, Depression, Stress and Anxiety in Patients with Coronary Artery Disease: Open Label, Randomized Trial. Life 2023, 13, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Donoghue, T.; Rabin, M. Choice and Procrastination. Q. J. Econ. 2001, 116, 121–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, R.T. Helping Students Confront and Deal with Stress and Procrastination. J. Coll. Stud. Psychother. 1992, 6, 87–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirois, F.M.; Melia-Gordon, M.L.; Pychyl, T.A. “I’ll look after my health, later”: An investigation of procrastination and health. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2003, 35, 1167–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fogg, B.J. Creating persuasive technologies: An eight-step design process. In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Persuasive Technology, Claremont, CA, USA, 26–29 April 2009; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Seels, B.; Richey, R. Instructional Technology: The Definition and Domains of the Field; Association for Educational Communications and Technology: Indianapolis, IN, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Brooke, J. SUS-A quick and dirty usability scale. Usability Eval. Ind. 1996, 189, 4–7. [Google Scholar]

- Nittayasupaporn, B.; Tohsen, F.; Poungpum, T.; Apipunyasopon, L. Development and assessment of CUFastTech mobile application for plain radiograph. Thai J. Radiol. Technol. 2021, 45, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Chomsri, P.; Henkaew, W.; Suratana, S.; Matrakul, M.; Soontranont, A.; Meethum, S.; Nooyai, T. The Research and Development of Health Literacy for Prevention Emergency Cardiovascular Disease System in Elderly through Community Participatory; Siampimnana Company Limited: Chiang Mai, Thailand, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Eckardt, I.; Buschhaus, C.; Nickenig, G.; Jansen, F. Smartphone-guided secondary prevention for patients with coronary artery disease. J. Rehabil. Assist. Technol. Eng. 2021, 8, 2055668321996572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saunders, C.H.; Sierpe, A.; von Plessen, C.; Kennedy, A.M.; Leviton, L.C.; Bernstein, S.L.; Goldwag, J.; King, J.R.; Marx, C.M.; Pogue, J.A.; et al. Practical thematic analysis: A guide for multidisciplinary health services research teams engaging in qualitative analysis. BMJ 2023, 381, e074256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noor Hanita, Z.; Khatijah, L.A.; Kamaruzzaman, S.; Karuthan, C.; Raja Mokhtar, R.A. A pilot study on development and feasibility of the ‘MyEducation: CABG application’ for patients undergoing coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgery. BMC Nurs. 2022, 21, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragheb, S.M.; Chudyk, A.; Kent, D.; Dave, M.G.; Hiebert, B.; Schultz, A.S.H.; Duhamel, T.A.; Arora, R.C. Use of a mobile health application by adult non-congenital cardiac surgery patients: A feasibility study. PLoS Digit. Health 2022, 1, e0000055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dithmer, M.; Rasmussen, J.O.; Grönvall, E.; Spindler, H.; Hansen, J.; Nielsen, G.; Sørensen, S.B.; Dinesen, B. “The Heart Game”: Using Gamification as Part of a Telerehabilitation Program for Heart Patients. Games Health J. 2016, 5, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cajita, M.I.; Gleason, K.T.; Han, H.R. A Systematic Review of mHealth-Based Heart Failure Interventions. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2016, 31, E10–E22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yardley, L.; Spring, B.J.; Riper, H.; Morrison, L.G.; Crane, D.H.; Curtis, K.; Merchant, G.C.; Naughton, F.; Blandford, A. Understanding and Promoting Effective Engagement With Digital Behavior Change Interventions. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2016, 51, 833–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, J.R.; Sauro, J. Item benchmarks for the system usability scale. J. Usability Stud. 2018, 13, 158–167. [Google Scholar]

- Klasnja, P.; Pratt, W. Healthcare in the pocket: Mapping the space of mobile-phone health interventions. J. Biomed. Inform. 2012, 45, 184–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleechaya, P. Digital Technology Utilization of Elderly and Framework for Promoting Thai Active and Productive Aging. J. Commun. Arts 2021, 39, 56–78. [Google Scholar]

- Lockwood, K.G.; Kulkarni, P.R.; Paruthi, J.; Buch, L.S.; Chaffard, M.; Schitter, E.C.; Branch, O.H.; Graham, S.A. Evaluating a New Digital App-Based Program for Heart Health: Feasibility and Acceptability Pilot Study. JMIR Form. Res. 2024, 8, e50446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, Y.; Liang, W.; Guo, L.; Zhan, H.; Xia, C.; Ma, H.; Shang, B.; Wang, Y.; Yang, M.; Cheng, S. Effectiveness of a WeChat Mini Program–Based Intervention on Promoting Multiple Health Behavior Changes Among Chinese Patients With Cardiovascular Diseases in Home-Based Rehabilitation: Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Med. Internet Res. 2025, 27, e66249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Rhoon, L.; Byrne, M.; Morrissey, E.; Murphy, J.; McSharry, J. A systematic review of the behaviour change techniques and digital features in technology-driven type 2 diabetes prevention interventions. Digit. Health 2020, 6, 2055207620914427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.; Choi, M.; Lee, S.A.; Jiang, N. Effective behavioral intervention strategies using mobile health applications for chronic disease management: A systematic review. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2018, 18, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iribarren, S.J.; Akande, T.O.; Kamp, K.J.; Barry, D.; Kader, Y.G.; Suelzer, E. Effectiveness of Mobile Apps to Promote Health and Manage Disease: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2021, 9, e21563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.; Kim, D.; Cho, S.; Han, H. Adoption of multimedia technology for learning and gender difference. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2019, 92, 288–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Questions | Additional Instructions |

|---|---|

| What do you like or dislike about the app? | Why do you like or dislike that part? |

| What part of the application do you find confusing or difficult to understand? | Can you tell a bit more about that? Why do you think that? How do you have suggestions for improving that parts? |

| Which part of the application do you think should be improved? | Is the design easy to use, including factors like color, font, and content? Why do you think that? Can you tell me more about that? |

| What makes you use the application consistently? | Do you use the application more, the same, or less than when you first started, and why? Which part of the app will make you use it consistently? Do you have a willingness to use the app if you do not participate in this study, and why? |

| What would be the reason for you to stop using the app? | Why do you think that? Do you have any suggestions? |

| What do you think about the knowledge content in the app? | Is knowledge content easy to understand? Does the knowledge content in the app enhance your understanding of heart disease and post-surgery recovery? Do you have any suggestions? |

| What do you think about the exercise program in the app? | Is exercise program easy to do? How do instructional exercise videos help you to do the exercise routine? Do you have any suggestions? |

| What do you think about the exercise tracking, both in terms of a calendar and visual representations illustrating the growth of a tree? | How does exercise tracking help in motivating you to work out? Do you have any suggestions on how to create motivation for exercising? |

| Characteristic | Value (n = 10) |

|---|---|

| Age, years (Mean ± SD) | 60.4 ± 10.0 |

| BMI, (kg/m2) (Mean ± SD) | 25.0 ± 3.5 |

| Gender, n (%) | |

| Male | 8 (80%) |

| Female | 2 (20%) |

| Educational Level, n (%) | |

| Primary | 1 (10%) |

| Secondary | 5 (50%) |

| Higher | 4 (40%) |

| Type of open-heart surgery, n (%) | |

| CABG | 5 (50%) |

| Valve Replacement | 4 (40%) |

| Others (aortic hemiarch replacement) | 1 (10%) |

| Comorbidities, n (%) | |

| Hypertension | 5 (50%) |

| Dyslipidemia | 3 (30%) |

| Diabetes Mellitus | 2 (20%) |

| Chronic Kidney Disease | 0 |

| Chronic Lung Disease | 1 (10%) |

| Others | 4 (40%) |

| Smoking status, n (%) | |

| Nonsmokers | 5 (10%) |

| Former smokers | 4 (10%) |

| Current smokers | 1 (10%) |

| Category | Score (n = 10) |

|---|---|

| 1. I think that I would like to use this application frequently | 4.2 ± 0.8 |

| 2. I found the application unnecessarily complex | 2.2 ± 0.8 |

| 3. I thought the application was easy to use | 4.7 ± 0.4 |

| 4. I think that I would need the support of a technical person to be able to use this application | 2.6 ± 1.3 |

| 5. I found the various functions in this application were well integrated | 4.2 ± 0.4 |

| 6. I thought there was too much inconsistency in this application | 1.7 ± 0.8 |

| 7. I would imagine that most people would learn to use this application very quickly | 4.5 ± 0.5 |

| 8. I found the application very cumbersome to use | 1.7 ± 0.4 |

| 9. I felt very confident using the application | 4.5 ± 0.5 |

| 10. I needed to learn a lot of things before I could get going with this application | 1.8 ± 0.4 |

| Category | Extremely (n) | Very (n) | Neutral (n) | Slightly (n) | Not at all (n) | Value (Mean ± SD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Contents | ||||||

| The information is useful to me | 5 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4.5 ± 0.5 |

| The information is clear | 4 | 5 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 4.3 ± 0.6 |

| Content is easy to understand | 6 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 4.5 ± 0.7 |

| Content quantity is appropriate | 3 | 6 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 4.2 ± 0.6 |

| Design of the application | ||||||

| The application makes it easy to learn | 4 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 4.2 ± 0.7 |

| Font size of letter is appropriate | 3 | 5 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 4.1 ± 0.7 |

| Overall composition of the application is appropriate | 2 | 4 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 3.8 ± 0.7 |

| Color of the screen is appropriate | 4 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4.4 ± 0.5 |

| Average | 4.3 ± 0.6 |

| Habits | 30-Day Before Intervention | 30-Day After Intervention |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Exercise or engage in physical activities | 2.3 ± 1.2 | 4.8 ± 0.6 |

| 2. Increased consumption of vegetables and fruits | 1.8 ± 1.0 | 3.9 ± 0.8 |

| 3. Reduced consumption of salt | 1.8 ± 1.0 | 4.5 ± 0.8 |

| 4. Reduced high-fat foods | 2.0 ± 1.0 | 4.4 ± 0.5 |

| 5. Reduced high-sugar foods | 2.1 ± 1.1 | 4.3 ± 0.8 |

| 6. Stress management | 3.0 ± 1.2 | 4.9 ± 0.3 |

| 7. Smoking cessation | 4.6 ± 1.2 | 4.7 ± 0.6 |

| 8. Reduced alcohol consumption | 5.0 ± 0.0 | 5.0 ± 0.0 |

| Themes | Subthemes | Sample Quotes from Participants |

|---|---|---|

| Content of the app is appropriate | Exercise programs are useful | “Well, it’s not that difficult. The good thing is I can follow the steps. It is very easy and beneficial.” (74-year-old Male) “Before the surgery, I didn’t exercise at all and I had no idea how to exercise after surgery. Then I used the app, it’s really good. I’ve learned how to do the exercises.” (44-year-old Female) “The exercise program is easy, and it worked for me.” (60-year-old Male) “I think the exercise sessions and breathing exercises are good.” (68-year-old Male) |

| Educational sessions are useful | “It can help me. The knowledge helps me get better.” (50-year-old Female) “Well, that’s good, it gives me knowledge that I didn’t know before.” (57-year-old Male) | |

| “It gives good knowledge, good content, clearly explained and easy to understand.” (51-year-old Male) | ||

| Motivation of exercise from the illustration metaphor | “Tracking exercise is very applicable. I can see if I did exercise today. The growth of the tree encourages me to exercise.” (72-year-old Male) | |

| “It’s like I added fertilizer to the tree. I was so happy when I saw the tree had grown. It’s fun to keep growing this tree. This made me want to do the exercise every day.” (78-year-old Male) “This is good. I saw the growth of the tree and it motivated me to do more exercise.” (60-year-old Male) | ||

| Design of the app is appropriate | Convenience and Ease of Use | “I’m not confused at all. It’s easy to use and understand.” (65-year-old Male) “It’s easy to learn and understand.” (50-year-old Female) “Explaining with images and videos is easy to understand and follow.” (68-year-old Male) |

| Barriers to use | User-friendly Technical issues | “I like the app telling me what to do in each step. I just follow that step.” (74-year-old Female) “As far as I can tell, it’s nothing complicated in the app. It explains well how to do exercise. Well, it’s easy to understand.” (44-year-old Female) “The guided videos help me to do the exercise better.” (60-year-old Male) “Sometimes it’s quite slow to response and stutters.” (60-year-old Male) “I’m not sure if it’s me or if it’s something that doesn’t work with my device. Sometimes, I can’t find the app.” (55-year-old Male) “Um, not sure if it’s the app itself or my own internet, because it lags often, and it freezes frequently. Then I have to pause, then play again. It’s quite annoying.” (44-year-old Female) |

| Familiarity of contents in the app | “Even without using the app, I can do the exercises because I already remember all the contents”. (51-year-old Male) “If the patient has recovered well, it may not be necessary to use the app.” (60-year-old Male) | |

| Suggestions for the app improvement | Addition of new exercise | “It could include various forms of exercises; patients might recover better.” (60-year-old Male) “Maybe add new types of exercises that patients don’t know about.” (51-year-old Male) |

| Format improvement | “The app is easy to understand by using pictures. But I think the color is not very pleasing.” (68-year-old Male) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Songsorn, P.; Nontasil, P.; Yuenyongchaiwat, K.; Charususin, N.; Laosiripisan, J.; Buranapuntalug, S.; Wattanananont, K. Development and Feasibility of a Smartphone Application for Promoting Healthy Heart Behaviors Following Open-Heart Surgery: A Mixed-Method Pilot Study. Healthcare 2025, 13, 1647. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13141647

Songsorn P, Nontasil P, Yuenyongchaiwat K, Charususin N, Laosiripisan J, Buranapuntalug S, Wattanananont K. Development and Feasibility of a Smartphone Application for Promoting Healthy Heart Behaviors Following Open-Heart Surgery: A Mixed-Method Pilot Study. Healthcare. 2025; 13(14):1647. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13141647

Chicago/Turabian StyleSongsorn, Preeyaphorn, Pawarat Nontasil, Kornanong Yuenyongchaiwat, Noppawan Charususin, Jitanan Laosiripisan, Sasipa Buranapuntalug, and Khanistha Wattanananont. 2025. "Development and Feasibility of a Smartphone Application for Promoting Healthy Heart Behaviors Following Open-Heart Surgery: A Mixed-Method Pilot Study" Healthcare 13, no. 14: 1647. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13141647

APA StyleSongsorn, P., Nontasil, P., Yuenyongchaiwat, K., Charususin, N., Laosiripisan, J., Buranapuntalug, S., & Wattanananont, K. (2025). Development and Feasibility of a Smartphone Application for Promoting Healthy Heart Behaviors Following Open-Heart Surgery: A Mixed-Method Pilot Study. Healthcare, 13(14), 1647. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13141647