Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices of Community Pharmacists Regarding Proton Pump Inhibitor (PPI) Use: A Cross-Sectional Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Instrument

2.3. Ethical Approval

2.4. Sample Size Calculation

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Knowledge of CPs Regarding PPI Use

4.2. Practices of CPs Toward PPI Use

4.3. Attitudes of CPs Regarding PPI Use

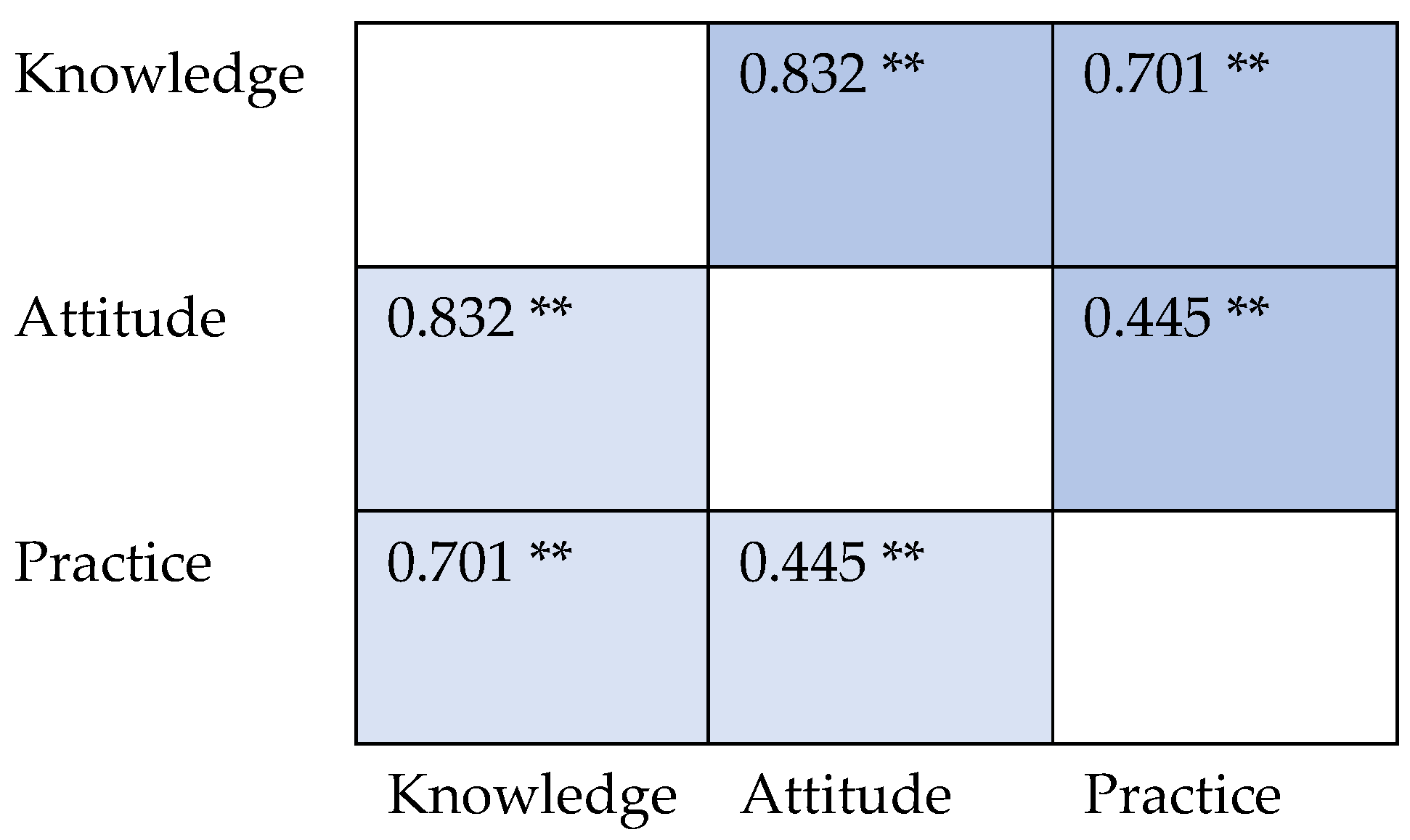

4.4. Influence of Demographics and Professional Characteristics on the KAPs of CPs

4.5. Recommendations

4.6. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| H2RAs | H2-receptor antagonists |

| PPIs | Proton pump inhibitors |

| OTC | Over the counter |

| CPs | Community pharmacists |

| KAPs | Knowledge, attitudes, and practices |

| NSAIDs | Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs |

| ADRs | Adverse drug reactions |

Appendix A

| Parameter |

| Sex |

| Female |

| Male |

| Years of experience |

| <1 |

| 1–4 |

| 5–10 |

| 11–20 |

| >20 |

| Highest degree |

| Bachelor of Pharmacy |

| PharmD |

| Master’s |

| Doctorate (PhD) |

| Country |

| Egypt |

| Iraq |

| Source of information about PPIs |

| Books |

| Research articles |

| Colleagues |

| Telegram |

| Lexi comp |

| Drug Eye |

| GeneBrandex |

| Egyptian knowledge bank |

| Guidelines |

| Parameter |

| Side effects caused by PPIs |

| Gastric carcinoids |

| Hip fractures |

| Hypomagnesemia |

| Nutritional deficiencies |

| Increased incidents of CVDs |

| Enteric infections |

| Diarrhea |

| Community-acquired pneumonia |

| Kidney diseases |

| Dementia |

| Change gut microbiota |

| Duodenal G-cell tumors |

| Anaphylaxis |

| Minerals and vitamins affected by PPIs |

| Calcium |

| Magnesium |

| Vitamin B12 |

| Manganese |

| Potassium |

| Sodium |

| Selenium |

| Types of ulcers treated by PPIs |

| NSAID-induced ulcer |

| Helicobacter pylori-induced ulcer |

| Stress ulcer prophylaxis |

| Drugs that interact with PPIs |

| Phenytoin |

| Warfarin |

| Clopidogrel |

| Atazanavir |

| Rilpivirine |

| Nelfinavir |

| Itraconazole |

| Ketoconazole |

| Posaconazole |

| What risk factors for ulcers and GI complications from NSAID use indicate the need for prophylactic PPIs? |

| Use of warfarin |

| Use of anticoagulant |

| Use of dexamethasone |

| High-dose NSAIDs |

| Longer duration of NSAIDs |

| Low dose of aspirin |

| PPIs are clinically inferior to H2Ras, False |

| Which of the following is correct? |

| All PPIs are OTC drugs |

| All PPIs are prescription-only medicine |

| Only some PPIs are OTC drugs |

| The administration of PPI with ticlopidine or clopidogrel or anti-coagulants alone without risk factors is recommended, False |

| In patients taking steroids alone for whatever clinical condition, mucosal protection with a PPI is routinely indicated, False |

| Sudden withdrawal of PPIs is not recommended, True |

| For which of the following categories of patients using NSAIDs and with no other risk factors are PPIs indicated for gastroprotection? |

| 45–55 years |

| 56–65 years |

| >65 years |

| Esomeprazole, lansoprazole, and omeprazole work best when taken: |

| 30 min before breakfast |

| After food |

| With food |

| What is the duration PPIs could be safely used without referring to a specialized physician? |

| 2 weeks |

| 2 months |

| 3 months |

| Indefinitely |

| In case of persistent and severe night symptoms, it is recommended to: |

| Take PPIs in the morning |

| Take PPIs before dinner |

| Fraction the daily dose into two separate administrations, one before breakfast and the other before dinner |

| PPI therapy should be prescribed to treat chronic laryngitis, False |

| PPIs can improve outcomes in Barrett’s esophagus, True |

| Like H2RA, PPIs can cause rapidly decreasing response to the drug (tachyphylaxis), False |

| Parameter |

| Provide advice for patients who use PPIs about lifestyle changes to alleviate their symptoms |

| Always |

| Often |

| Sometimes |

| Rarely |

| Never |

| Contact the prescriber or advise the patient to stop PPIs when there is no current indication for their use |

| Always |

| Often |

| Sometimes |

| Rarely |

| Never |

| Report ADR of PPIs to the manufacturer or regulatory authorities |

| Always |

| Often |

| Sometimes |

| Rarely |

| Never |

| Consider PPIs the first choice when recommending acid-suppression drugs |

| Always |

| Often |

| Sometimes |

| Rarely |

| Never |

| Prescribe PPIs for patients, Yes |

| Use guidelines such as the JSGE or ACG when prescribing PPIs, Yes |

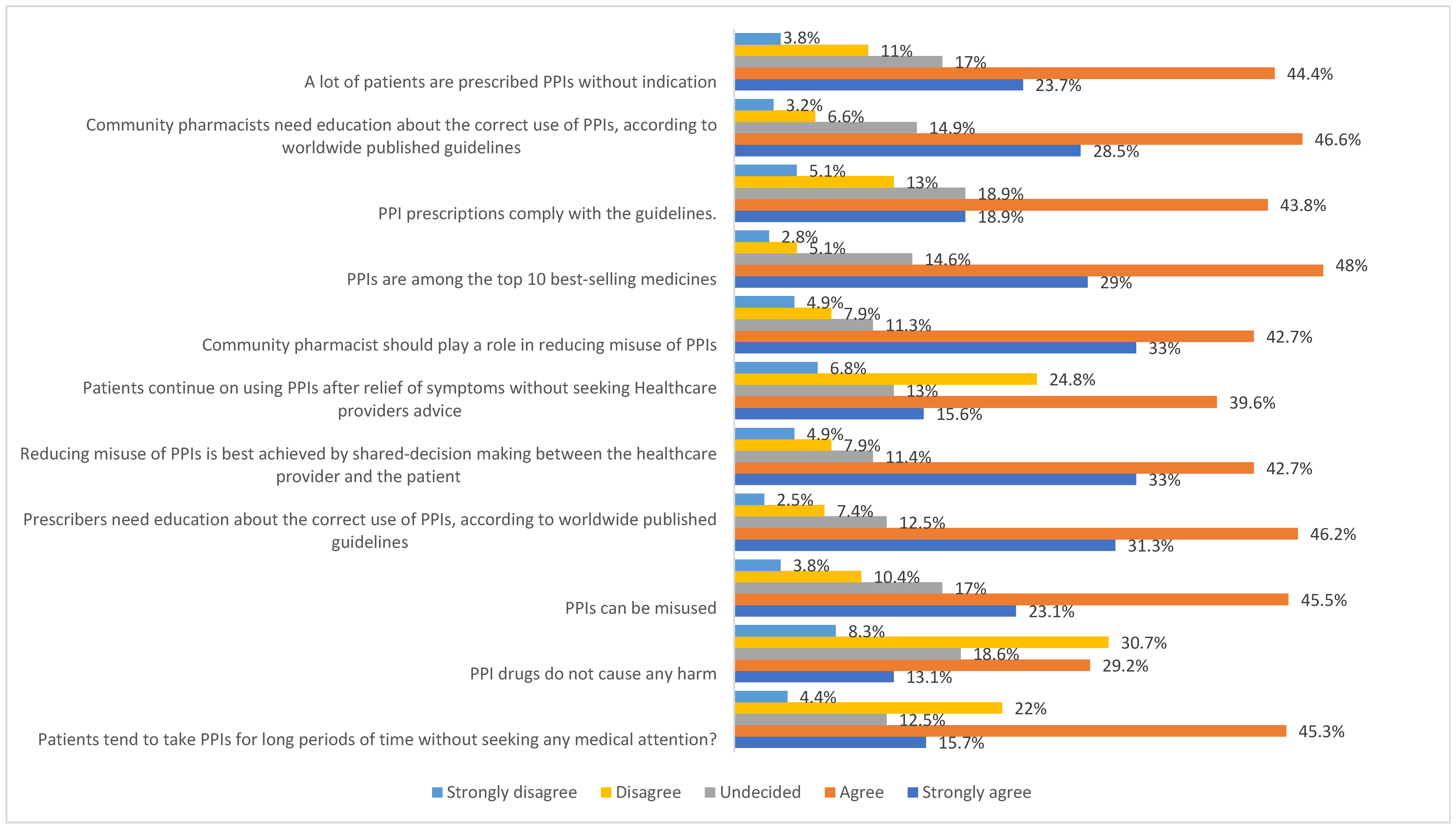

| 1—Do you think patients tend to take PPIs for long periods of time without seeking any medical attention? | Strongly disagree Disagree Undecided Agree Strongly agree |

| 2—PPI drugs do not cause any harm. | Strongly disagree Disagree Undecided Agree Strongly agree |

| 3—Do you think there is a misuse of PPIs? | Strongly disagree Disagree Undecided Agree Strongly agree |

| 4—Do you think prescribers need education about the correct use of PPIs, according to worldwide published guidelines? | Strongly disagree Disagree Undecided Agree Strongly agree |

| 5—Do you think that reducing misuse of PPIs is best achieved by shared decision-making between the healthcare provider and the patient? | Strongly disagree Disagree Undecided Agree Strongly agree |

| 6—Patients continue using PPIs after relief of symptoms without seeking healthcare providers’ advice. | Strongly disagree Disagree Undecided Agree Strongly agree |

| 7—Community pharmacists should play a role in reducing misuse of PPIs. | Strongly disagree Disagree Undecided Agree Strongly agree |

| 8—PPIs are among the top 10 best-selling medicines. | Strongly disagree Disagree Undecided Agree Strongly agree |

| 9—PPI prescriptions comply with the guidelines. | Strongly disagree Disagree Undecided Agree Strongly agree |

| 10—Do you think community pharmacists need education about the correct use of PPIs according to worldwide published guidelines? | Strongly disagree Disagree Undecided Agree Strongly agree |

| 11—Do you think a lot of patients are prescribed PPIs without indication? | Strongly disagree Disagree Undecided Agree Strongly agree |

References

- Kherad, O.; Restellini, S.; Martel, M.; Barkun, A. Proton Pump Inhibitors for Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding. Best. Pract. Res. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2019, 42–43, 101609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savarino, V.; Marabotto, E.; Zentilin, P.; Furnari, M.; Bodini, G.; De Maria, C.; Pellegatta, G.; Coppo, C.; Savarino, E. Proton Pump Inhibitors: Use and Misuse in the Clinical Setting. Expert. Rev. Clin. Pharmacol. 2018, 11, 1123–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Aly, Z.; Maddukuri, G.; Xie, Y. Proton Pump Inhibitors and the Kidney: Implications of Current Evidence for Clinical Practice and When and How to Deprescribe. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2020, 75, 497–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, K.; Adler, N.; Agrawal, D.; Bhakta, D.; Sata, S.S.; Singh, S.; Gupta, A.; Pahwa, A.; Pherson, E.; Sun, A.; et al. Indications for the Use of Proton Pump Inhibitors for Stress Ulcer Prophylaxis and Peptic Ulcer Bleeding in Hospitalized Patients. Am. J. Med. 2022, 135, 313–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sigterman, K.E.; van Pinxteren, B.; Bonis, P.A.; Lau, J.; Numans, M.E. Short-Term Treatment with Proton Pump Inhibitors, H2-Receptor Antagonists and Prokinetics for Gastro-Oesophageal Reflux Disease-like Symptoms and Endoscopy Negative Reflux Disease. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2013, 2013, CD002095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lassalle, M.; Le Tri, T.; Bardou, M.; Biour, M.; Kirchgesner, J.; Rouby, F.; Dumarcet, N.; Zureik, M.; Dray-Spira, R. Use of Proton Pump Inhibitors in Adults in France: A Nationwide Drug Utilization Study. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2020, 76, 449–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, T.; Roberts, D.N.; Tierney, W.M. Long-Term Safety Concerns with Proton Pump Inhibitors. Am. J. Med. 2009, 122, 896–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhardwaj, S.; Garvin, S.; Kuehl, S.; Van Epps, J.; Dunkerson, F.; Lehmann, M.; Gruber, S.; Kieser, M.; Zhao, Q.; Portillo, E.C. Incorporation of Student Pharmacists into a Proton Pump Inhibitor Deprescribing Telehealth Program for Rural Veterans. Innov. Pharm. 2022, 13, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madi, L.; Ahmed Elhada, A.; Alrawashdeh, H.; Ahmed, A. Prescribing Pattern of Proton Pump Inhibitors in Qatar Rehabilitation Institute: A Retrospective Study. J. Res. Pharm. Pract. 2019, 8, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solem, C.; Mody, R.; Stephens, J.; Macahilig, C.; Gao, X. Mealtime-Related Dosing Directions for Proton-Pump Inhibitors in Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease: Physician Knowledge, Patient Adherence. J. Am. Pharm. Assoc. 2014, 54, 144–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Giorno, R.; Ceschi, A.; Pironi, M.; Zasa, A.; Greco, A.; Gabutti, L. Multifaceted Intervention to Curb In-Hospital over-Prescription of Proton Pump Inhibitors: A Longitudinal Multicenter Quasi-Experimental before-and-after Study. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2018, 50, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewis, J.R.; Barre, D.; Zhu, K.; Ivey, K.L.; Lim, E.M.; Hughes, J.; Prince, R.L. Long-Term Proton Pump Inhibitor Therapy and Falls and Fractures in Elderly Women: A Prospective Cohort Study. J. Bone Min. Res. 2014, 29, 2489–2497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, J.; Chan, A.T.; Zeng, C.; Bai, X.; Lu, N.; Lei, G.; Zhang, Y. Association between Proton Pump Inhibitors Use and Risk of Hip Fracture: A General Population-Based Cohort Study. Bone 2020, 139, 115502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Welu, J.; Metzger, J.; Bebensee, S.; Ahrendt, A.; Vasek, M. Proton Pump Inhibitor Use and Risk of Dementia in the Veteran Population. Fed. Pract. 2019, 36, S27–S31. [Google Scholar]

- Abraham, N.S. Proton Pump Inhibitors: Potential Adverse Effects. Curr. Opin. Gastroenterol. 2012, 28, 615–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, J.S.; Park, S.M.; Eom, C.S.; Kim, S.; Myung, S.-K. Use of Proton Pump Inhibitor and Risk of Colorectal Cancer: A Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies. Korean J. Fam. Med. 2012, 33, 272–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundell, L.; Vieth, M.; Gibson, F.; Nagy, P.; Kahrilas, P.J. Systematic Review: The Effects of Long-Term Proton Pump Inhibitor Use on Serum Gastrin Levels and Gastric Histology. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2015, 42, 649–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Bowe, B.; Li, T.; Xian, H.; Yan, Y.; Al-Aly, Z. Risk of Death among Users of Proton Pump Inhibitors: A Longitudinal Observational Cohort Study of United States Veterans. BMJ Open 2017, 7, e015735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhossan, A.; Alrabiah, Z.; Alghadeer, S.; Bablghaith, S.; Wajid, S.; Al-Arifi, M. Attitude and Knowledge of Saudi Community Pharmacists towards Use of Proton Pump Inhibitors. Saudi Pharm. J. 2019, 27, 225–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljahdli, E.S.; Mokhtar, A.M.; Aljehani, S.A.; Hamdi, R.M.; Alsubhi, B.H.; Aljuhani, K.F.; Saleh, K.A.; Alzoriri, A.D.; Alghamdi, W.S. Assessment of Awareness and Knowledge of Proton Pump Inhibitors Among the General Population in Saudi Arabia. Cureus 2022, 14, e27149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoteit, M.; Mattar, E.; Allaw, R.; Abou Rached, A. Epidemiological Study Assessing the Overuse of Proton Pump Inhibitors in Lebanese Population. Middle East. J. Dig. Dis. 2020, 12, 265–270. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gharaibeh, L.; Alameri, M.A.; AL-Hawamdeh, M.I.; Daoud, E.; Atwan, R.; Lafi, Z.; Zakaraya, Z.Z. Practices and Knowledge of Community Pharmacists towards the Use of Proton Pump Inhibitors: A Cross-Sectional Study in Jordan. BMJ Open 2025, 15, e085589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farrell, B.; Pottie, K.; Thompson, W.; Boghossian, T.; Pizzola, L.; Rashid, F.J.; Rojas-Fernandez, C.; Walsh, K.; Welch, V.; Moayyedi, P. Deprescribing Proton Pump Inhibitors: Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guideline. Can. Fam. Physician 2017, 63, 354–364. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gendre, P.; Mayol, S.; Mocquard, J.; Huon, J. Physicians’ Views on Pharmacists’ Involvement in Hospital Deprescribing: A Qualitative Study on Proton Pump Inhibitors. Basic Clin. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2023, 133, 718–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghunath, A.S.; Hungin, A.P.S.; Cornford, C.S.; Featherstone, V. Use of Proton Pump Inhibitors: An Exploration of the Attitudes, Knowledge and Perceptions of General Practitioners. Digestion 2005, 72, 212–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dills, H.; Shah, K.; Messinger-Rapport, B.; Bradford, K.; Syed, Q. Deprescribing Medications for Chronic Diseases Management in Primary Care Settings: A Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2018, 19, 923–935.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, W.; Farrell, B.; Welch, V.; Tugwell, P.; Way, C.; Richardson, L.; Bjerre, L.M. Continuation or Deprescribing of Proton Pump Inhibitors: A Consult Patient Decision Aid. Can. Pharm. J./Rev. Pharm. Can. 2018, 152, 18–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awad, A.; Al-Tunaib, A.; Al-Saraf, S. Physicians’ Perceptions and Awareness of Adverse Effects of Proton Pump Inhibitors and Impact on Prescribing Patterns. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 15, 1383698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassem, A.B.; Al Meslamani, A.Z.; Elmaghraby, D.H.; Magdy, Y.; AbdElrahman, M.; Hamdan, A.M.E.; Mohamed Moustafa, H.A. The Pharmacists’ Interventions after a Drug and Therapeutics Committee (DTC) Establishment during the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Pharm. Policy Pract. 2024, 17, 2372040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chhabra, P.; Ingole, N. Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (GERD): Highlighting Diagnosis, Treatment, and Lifestyle Changes. Cureus 2022, 14, e28563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yailian, A.; Huet, E.; Charpiat, B.; Conort, O.; Juste, M.; Roubille, R.; Bourdelin, M.; Gravoulet, J.; Mongaret, C.; Vermorel, C.; et al. Characteristics of Pharmacists’ Interventions Related to Proton-Pump Inhibitors in French Hospitals: An Observational Study. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2022, 2022, 9619699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agee, C.; Coulter, L.; Hudson, J. Effects of Pharmacy Resident Led Education on Resident Physician Prescribing Habits Associated with Stress Ulcer Prophylaxis in Non-Intensive Care Unit Patients. Am. J. Health Syst. Pharm. 2015, 72, S48–S52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, H.; Fan, Q.; Xiao, S.; Chen, K. Impact of Clinical Pharmacist Interventions on Inappropriate Prophylactic Acid Suppressant Use in Hepatobiliary Surgical Patients Undergoing Elective Operations. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0186302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Jumaili, A.A.; Ahmed, K.K. A Review of Antibiotic Misuse and Bacterial Resistance in Iraq. East. Mediterr. Health J. 2024, 30, 663–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanctis, V.D.; Soliman, A.T.; Daar, S.; Maio, S.D.; Elalaily, R.; Fiscina, B.; Kattamis, C. Prevalence, Attitude and Practice of Self-Medication among Adolescents and the Paradigm of Dysmenorrhea Self-Care Management in Different Countries. Acta Bio Medica Atenei Parm. 2020, 91, 182–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, H.; Fan, Q.; Bian, T.; Li, X.; Chen, K.; Zhang, Q.; Wei, Y.; Xiao, Y.; Li, Y. Awareness, Attitude and Behavior Regarding Proton Pump Inhibitor among Medical Staff in the Southwest of China. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2019, 19, 880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swed, S.; Alibrahim, H.; Bohsas, H.; Ibrahim, A.R.N.; Siddiq, A.; Jawish, N.; Makhoul, M.H.; Alrezej, M.A.M.; Makhoul, F.H.; Sawaf, B.; et al. Evaluating Physicians’ Awareness and Prescribing Trends Regarding Proton Pump Inhibitors: A Cross-Sectional Study. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14, 1241766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Targownik, L.E.; Fisher, D.A.; Saini, S.D. AGA Clinical Practice Update on De-Prescribing of Proton Pump Inhibitors: Expert Review. Gastroenterology 2022, 162, 1334–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurlander, J.E.; Helminski, D.; Kokaly, A.N.; Richardson, C.R.; De Vries, R.; Saini, S.D.; Krein, S.L. Barriers to Guideline-Based Use of Proton Pump Inhibitors to Prevent Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding. Ann. Fam. Med. 2022, 20, 5–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boardman, H.F.; Heeley, G. The Role of the Pharmacist in the Selection and Use of Over-the-Counter Proton-Pump Inhibitors. Int. J. Clin. Pharm. 2015, 37, 709–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moustafa, H.A.M.; Wen, M.M.; AbdElrahman, M.; Hamdan, A.M.E.; Alkhamali, A. Psychological Challenges Faced Community Pharmacists during COVID-19 Pandemic: A Cross-Sectional Study. Pharm. Pract. 2025, 23, 1886–3655. [Google Scholar]

- Hamurtekin, E.; Bosnak, A.; Azarbad, A.; Moghaddamshahabi, R.; Hamurtekin, Y.; Naser, R. Knowledge, Attitude, and Practices Regarding Proton Pump Inhibitors among Community Pharmacists and Pharmacy Students. Niger. J. Clin. Pract. 2023, 26, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghosh, G.; Schnoll-Sussman, F.; Mathews, S.; Katz, P.O. Reported Proton Pump Inhibitor Side Effects: What Are Physician and Patient Perspectives and Behaviour Patterns? Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2020, 51, 121–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerra-Farfan, E.; Garcia-Sanchez, Y.; Jornet-Gibert, M.; Nuñez, J.H.; Balaguer-Castro, M.; Madden, K. Clinical Practice Guidelines: The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly. Injury 2023, 54 (Suppl. S3), S26–S29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donder, C.G. Keeping up with the Evidence. Can. Pharm. J./Rev. Pharm. Can. 2017, 150, 98–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giebel, G.D.; Speckemeier, C.; Abels, C.; Plescher, F.; Börchers, K.; Wasem, J.; Blase, N.; Neusser, S. Problems and Barriers Related to the Use of Digital Health Applications: Scoping Review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2023, 25, e43808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woolf, A.; Rose, R. Gastric Ulcer. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Marie, I.; Moutot, A.; Tharrasse, A.; Hellot, M.-F.; Robaday, S.; Hervé, F.; Lévesque, H. Validity of proton pump inhibitors’ prescriptions in a department of internal medicine. Rev. Med. Interne 2007, 28, 86–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahme, E.; Barkun, A.N.; Toubouti, Y.; Scalera, A.; Rochon, S.; Lelorier, J. Do Proton-Pump Inhibitors Confer Additional Gastrointestinal Protection in Patients given Celecoxib? Arthritis Rheum. 2007, 57, 748–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voukelatou, P.; Vrettos, I.; Emmanouilidou, G.; Dodos, K.; Skotsimara, G.; Kontogeorgou, D.; Kalliakmanis, A. Predictors of Inappropriate Proton Pump Inhibitors Use in Elderly Patients. Curr. Gerontol. Geriatr. Res. 2019, 2019, 7591045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, W.A.; Chung, C.P.; Murray, K.T.; Smalley, W.E.; Daugherty, J.R.; Dupont, W.D.; Stein, C.M. Association of Proton Pump Inhibitors With Reduced Risk of Warfarin-Related Serious Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding. Gastroenterology 2016, 151, 1105–1112.e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ntaios, G.; Chatzinikolaou, A.; Kaiafa, G.; Savopoulos, C.; Hatzitolios, A.; Karamitsos, D. Evaluation of Use of Proton Pump Inhibitors in Greece. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2009, 20, 171–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savarino, V.; Dulbecco, P.; de Bortoli, N.; Ottonello, A.; Savarino, E. The Appropriate Use of Proton Pump Inhibitors (PPIs): Need for a Reappraisal. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2017, 37, 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scarpignato, C.; Gatta, L.; Zullo, A.; Blandizzi, C.; SIF-AIGO-FIMMG Group; Italian Society of Pharmacology, the Italian Association of Hospital Gastroenterologists, and the Italian Federation of General Practitioners. Effective and Safe Proton Pump Inhibitor Therapy in Acid-Related Diseases—A Position Paper Addressing Benefits and Potential Harms of Acid Suppression. BMC Med. 2016, 14, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Q.; Yuan, C.; Zhou, S.; Lu, J.; Zeng, M.; Cai, X.; Song, H. Helicobacter Pylori Infection: A Dynamic Process from Diagnosis to Treatment. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2023, 13, 1257817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardou, M.; Quenot, J.-P.; Barkun, A. Stress-Related Mucosal Disease in the Critically Ill Patient. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2015, 12, 98–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shears, M.; Alhazzani, W.; Marshall, J.C.; Muscedere, J.; Hall, R.; English, S.W.; Dodek, P.M.; Lauzier, F.; Kanji, S.; Duffett, M.; et al. Stress Ulcer Prophylaxis in Critical Illness: A Canadian Survey. Can. J. Anaesth. 2016, 63, 718–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bez, C.; Perrottet, N.; Zingg, T.; Leung Ki, E.-L.; Demartines, N.; Pannatier, A. Stress Ulcer Prophylaxis in Non-Critically Ill Patients: A Prospective Evaluation of Current Practice in a General Surgery Department. J. Eval. Clin. Pract. 2013, 19, 374–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holtmann, G.; Bigard, M.-A.; Malfertheiner, P.; Pounder, R. Guidance on the Use of Over-the-Counter Proton Pump Inhibitors for the Treatment of GERD. Int. J. Clin. Pharm. 2011, 33, 493–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savarino, V.; Mela, G.S.; Zentilin, P.; Bisso, G.; Pivari, M.; Vigneri, S.; Termini, R.; Fiorucci, S.; Usai, P.; Malesci, A.; et al. Comparison of 24-h Control of Gastric Acidity by Three Different Dosages of Pantoprazole in Patients with Duodenal Ulcer. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 1998, 12, 1241–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ksiądzyna, D.; Szeląg, A.; Paradowski, L. Overuse of Proton Pump Inhibitors. Pol. Arch. Med. Wewnętrznej 2015, 125, 289–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malesci, A.; Savarino, V.; Zentilin, P.; Belicchi, M.; Mela, G.S.; Lapertosa, G.; Bocchia, P.; Ronchi, G.; Franceschi, M. Partial Regression of Barrett’s Esophagus by Long-Term Therapy with High-Dose Omeprazole. Gastrointest. Endosc. 1996, 44, 700–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chey, W.D.; Mody, R.R.; Izat, E. Patient and Physician Satisfaction with Proton Pump Inhibitors (PPIs): Are There Opportunities for Improvement? Dig. Dis. Sci. 2010, 55, 3415–3422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Araújo, L.M.L.; de Moura Lopes, M.V.; de Arruda, R.S.; Martins, R.R.; Oliveira, A.G. Proton Pump Inhibitor and Community Pharmacies: Usage Profile and Factors Associated with Long-Term Use. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0252785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochoa, D.; Román, M.; Cabaleiro, T.; Saiz-Rodríguez, M.; Mejía, G.; Abad-Santos, F. Effect of Food on the Pharmacokinetics of Omeprazole, Pantoprazole and Rabeprazole. BMC Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2020, 21, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moustafa, H.A.M.; Hamid, A.E.; Hassoub, G.; Kassem, A.B. Assessing the Impact of Critical Care Training on Pharmacy Students in Egypt: A Pre-Post Study. BMC Med. Educ. 2024, 24, 1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giuliano, C.; Wilhelm, S.M.; Kale-Pradhan, P.B. Are Proton Pump Inhibitors Associated with the Development of Community-Acquired Pneumonia? A Meta-Analysis. Expert. Rev. Clin. Pharmacol. 2012, 5, 337–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fohl, A.L.; Regal, R.E. Proton Pump Inhibitor-Associated Pneumonia: Not a Breath of Fresh Air after All? World J. Gastrointest. Pharmacol. Ther. 2011, 2, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, X.; Yang, Z. Association between Hospital-Acquired Pneumonia and Proton Pump Inhibitor Prophylaxis in Patients Treated with Glucocorticoids: A Retrospective Cohort Study Based on 307,622 Admissions in China. J. Thorac. Dis. 2022, 14, 2022–2033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imhann, F.; Bonder, M.J.; Vich Vila, A.; Fu, J.; Mujagic, Z.; Vork, L.; Tigchelaar, E.F.; Jankipersadsing, S.A.; Cenit, M.C.; Harmsen, H.J.M.; et al. Proton Pump Inhibitors Affect the Gut Microbiome. Gut 2016, 65, 740–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, X.; Zhang, X.; Wang, J.; Liu, Y.; Yan, H.; Xing, X.; Yang, J. Proton Pump Inhibitors Alter Gut Microbiota by Promoting Oral Microbiota Translocation: A Prospective Interventional Study. Gut 2024, 73, 1098–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinzon, D.; Domingues, G.; Tosetto, N.; Perrotti, M. Safety of Long-Term Proton Pump Inhibitors: Facts and Myths. Arq. Gastroenterol. 2022, 59, 219–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rababa, M.; Rababa’h, A. Community-Dwelling Older Adults’ Awareness of the Inappropriate Use of Proton Pump Inhibitors. BMC Geriatr. 2020, 20, 431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smaoui, H.; Chtourou, L.; Jallouli, D.; Jemaa, S.B.; Karaa, I.; Boudabbous, M.; Moalla, M.; Gdoura, H.; Mnif, L.; Amouri, A.; et al. Effect of Long-Term Proton Pump Inhibitors on Phosphocalcium Metabolism and Bone Mineral Density. Future Sci. OA 2024, 10, FSO977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freedberg, D.E.; Kim, L.S.; Yang, Y.-X. The Risks and Benefits of Long-Term Use of Proton Pump Inhibitors: Expert Review and Best Practice Advice From the American Gastroenterological Association. Gastroenterology 2017, 152, 706–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mares-García, E.; Palazón-Bru, A.; Martínez-Martín, Á.; Folgado-de la Rosa, D.M.; Pereira-Expósito, A.; Gil-Guillén, V.F. Non-Guideline-Recommended Prescribing of Proton Pump Inhibitors in the General Population. Curr. Med. Res. Opin. 2017, 33, 1725–1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarus, B.; Chen, Y.; Wilson, F.P.; Sang, Y.; Chang, A.R.; Coresh, J.; Grams, M.E. Proton Pump Inhibitor Use and the Risk of Chronic Kidney Disease. JAMA Intern. Med. 2016, 176, 238–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Liu, F.; Chen, C.; Zhu, W.; Ma, J.; Hu, J.; Xu, J.; Hong, K. Real-World Relationship Between Proton Pump Inhibitors and Cerebro-Cardiovascular Outcomes Independent of Clopidogrel. Int. Heart J. 2019, 60, 910–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alolabi, R.; Liem, J.J. Pantoprazole-Induced Anaphylaxis. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2019, 143, AB73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, P.P.; Bhandari, R.; Mishra, D.R.; Agrawal, K.K.; Bhandari, R.; Jirel, S.; Malla, G. Anaphylactic Reactions Due to Pantoprazole: Case Report of Two Cases. Int. Med. Case Rep. J. 2018, 11, 125–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Telaku, S.; Veliu, A.; Zenelaj, Q.; Telaku, M.; Fejza, H.; Alidema, F. Anaphylaxis Caused by Taking Pantoprazole: Case Series. Eur. J. Case Rep. Intern. Med. 2023, 10, 004017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hungin, A.P.S.; Hill, C.; Molloy-Bland, M.; Raghunath, A. Systematic Review: Patterns of Proton Pump Inhibitor Use and Adherence in Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2012, 10, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, K.S.; Chan, E.W.; Wong, A.Y.S.; Chen, L.; Wong, I.C.K.; Leung, W.K. Long-Term Proton Pump Inhibitors and Risk of Gastric Cancer Development after Treatment for Helicobacter Pylori: A Population-Based Study. Gut 2018, 67, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCarthy, D.M. Proton Pump Inhibitor Use, Hypergastrinemia, and Gastric Carcinoids-What Is the Relationship? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haastrup, P.F.; Thompson, W.; Søndergaard, J.; Jarbøl, D.E. Side Effects of Long-Term Proton Pump Inhibitor Use: A Review. Basic Clin. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2018, 123, 114–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namikawa, K.; Björnsson, E.S. Rebound Acid Hypersecretion after Withdrawal of Long-Term Proton Pump Inhibitor (PPI) Treatment-Are PPIs Addictive? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 5459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, I.E.; Sonu, I.; Scarpignato, C.; Akiyama, J.; Hongo, M.; Vega, K.J. Potential Proton Pump Inhibitor-Related Adverse Effects. Ann. N. Y Acad. Sci. 2020, 1481, 43–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Disney, B.R.; Watson, R.D.S.; Blann, A.D.; Lip, G.Y.H.; Anderson, M.R. Review Article: Proton Pump Inhibitors with Clopidogrel--Evidence for and against a Clinically-Important Interaction. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2011, 33, 758–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maret-Ouda, J.; Santoni, G.; Xie, S.; Rosengren, A.; Lagergren, J. Proton Pump Inhibitor and Clopidogrel Use After Percutaneous Coronary Intervention and Risk of Major Cardiovascular Events. Cardiovasc. Drugs Ther. 2022, 36, 1121–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, A.N.; Atwell, C.L.; Yoo, W.; Solomon, S.S. Vitamin B(12) Deficiency Associated with Concomitant Metformin and Proton Pump Inhibitor Use. Diabetes Care 2012, 35, e84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheungpasitporn, W.; Thongprayoon, C.; Kittanamongkolchai, W.; Srivali, N.; Edmonds, P.J.; Ungprasert, P.; O’Corragain, O.A.; Korpaisarn, S.; Erickson, S.B. Proton Pump Inhibitors Linked to Hypomagnesemia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies. Ren. Fail. 2015, 37, 1237–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alblooshi, A.J.; Baig, M.R.; Anbar, H.S. Patients’ Knowledge and Pharmacists’ Practice Regarding the Long-Term Side Effects of Proton Pump Inhibitors; a Cross-Sectional Study. Arch. Acad. Emerg. Med. 2024, 12, e35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turshudzhyan, A.; Samuel, S.; Tawfik, A.; Tadros, M. Rebuilding Trust in Proton Pump Inhibitor Therapy. World J. Gastroenterol. 2022, 28, 2667–2679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Othman, F.; Card, T.R.; Crooks, C.J. Proton Pump Inhibitor Prescribing Patterns in the UK: A Primary Care Database Study. Pharmacoepidemiol. Drug Saf. 2016, 25, 1079–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Qaisi, M.T.; Kahn, A.; Crowell, M.D.; Burdick, G.E.; Vela, M.F.; Ramirez, F.C. Do Recent Reports about the Adverse Effects of Proton Pump Inhibitors Change Providers’ Prescription Practice? Dis. Esophagus 2018, 31, doy042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matuz, M.; Benkő, R.; Engi, Z.; Schváb, K.; Doró, P.; Viola, R.; Szabó, M.; Soós, G. Use of Proton Pump Inhibitors in Hungary: Mixed-Method Study to Reveal Scale and Characteristics. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 552102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishuk, A.U.; Chen, L.; Gaillard, P.; Westrick, S.; Hansen, R.A.; Qian, J. National Trends in Prescription Proton Pump Inhibitor Use and Expenditure in the United States in 2002–2017. J. Am. Pharm. Assoc. 2021, 61, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotman, S.R.; Bishop, T.F. Proton Pump Inhibitor Use in the U.S. Ambulatory Setting, 2002–2009. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e56060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazberuk, M.; Brzósko, S.; Hryszko, T.; Naumnik, B. Overuse of Proton Pump Inhibitors and Its Consequences. Postep. Hig. Med. Dosw. (Online) 2016, 70, 1112–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Mamtani, R.; Scott, F.I.; Goldberg, D.S.; Haynes, K.; Lewis, J.D. Increasing Use of Prescription Drugs in the United Kingdom. Pharmacoepidemiol. Drug Saf. 2016, 25, 628–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lodato, F.; Poluzzi, E.; Raschi, E.; Piccinni, C.; Koci, A.; Olivelli, V.; Napoli, C.; Corvalli, G.; Nalon, E.; De Ponti, F.; et al. Appropriateness of Proton Pump Inhibitor (PPI) Prescription in Patients Admitted to Hospital: Attitudes of General Practitioners and Hospital Physicians in Italy. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2016, 30, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asdaq, S.M.B.; ALbasha, M.; Almutairi, A.; Alyabisi, R.; Almuhaisni, A.; Faqihi, R.; Alamri, A.S.; Alsanie, W.F.; Alhomrani, M. Use of Proton Pump Inhibitors: An Exploration of Awareness, Attitude and Behavior of Health Care Professionals of Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Saudi Pharm. J. 2021, 29, 713–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bright, T.J.; Wong, A.; Dhurjati, R.; Bristow, E.; Bastian, L.; Coeytaux, R.R.; Samsa, G.; Hasselblad, V.; Williams, J.W.; Musty, M.D.; et al. Effect of Clinical Decision-Support Systems: A Systematic Review. Ann. Intern. Med. 2012, 157, 29–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Recommendations|Gastro-Oesophageal Reflux Disease and Dyspepsia in Adults: Investigation and Management|Guidance|NICE. Available online: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg184/chapter/recommendations (accessed on 10 February 2025).

- Martin, P.; Tamblyn, R.; Ahmed, S.; Benedetti, A.; Tannenbaum, C. A Consumer-Targeted, Pharmacist-Led, Educational Intervention to Reduce Inappropriate Medication Use in Community Older Adults (D-PRESCRIBE Trial): Study Protocol for a Cluster Randomized Controlled Trial. Trials 2015, 16, 266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvini, G.; Baiardi, G.; Mattioli, F.; Milano, G.; Calautti, F.; Zunino, A.; Fraguglia, C.; Caccavale, F.; Lantieri, F.; Antonucci, G. Deprescribing Strategies: A Prospective Study on Proton Pump Inhibitors. JCM 2023, 12, 3029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Parameter | Total, n (%) | Knowledge Score (IQR) | Attitude Score, (IQR) | Practice Score, (IQR) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | p value | p value | p value | ||||

| Female | 252 (47.8%) | 8 (6–9) | 0.147 | 9 (6–11) | 0.912 | 6 (4–8) | 0.796 |

| Male | 275 (52.2%) | 9 (8–12) | 9 (6–9) | 6 (3–12) | |||

| Years of experience | |||||||

| <1 | 106 (20.1%) | 7 (6–7) | 0.001 | 7 (5–9) | 0.121 | 5 (4–7) | 0.021 |

| 1–4 | 209 (39.7%) | 7 (5–8) | 7 (5–9) | 6 (4–8) | |||

| 5–10 | 102 (19.4%) | 8 (6–9) | 9 (8–12) | 7 (3–9) | |||

| 11–20 | 35 (6.6%) | 7 (6–8) | 9 (6–10) | 7 (5–8) | |||

| >20 | 75 (14.2%) | 11 (6–14) | 10 (8–12) | 8 (4–12) | |||

| Highest degree | |||||||

| Bachelor of Pharmacy | 368 (69.8%) | 6 (4–8) | 0.621 | 8 (7–9) | 0.145 | 6 (4–7) | 0.228 |

| PharmD | 56 (10.6%) | 9 (6–12) | 7 (6–12) | 6 (4–6) | |||

| Master’s | 50 (9.5%) | 8 (7–9) | 10 (7–10) | 5 (3–8) | |||

| Doctorate (PhD) | 53 (10.1%) | 7 (6–15) | 8 (6–8) | 7 (3–11) | |||

| Country | |||||||

| Egypt | 336 (63.8%) | 9 (6–14) | 0.897 | 9 (7–11) | 0.089 | 6 (4–6) | 0.689 |

| Iraq | 191 (36.2%) | 9 (7–15) | 10 (9–12) | 6 (5–8) | |||

| Source of information about PPIs | |||||||

| Books | 190 (36.1%) | 7 (6–8) | 0.028 | 8 (7–9) | 0.105 | 6 (4–8) | 0.239 |

| Research articles | 219 (41.6%) | 9 (8–14) | 9 (6–10) | 5 (3–7) | |||

| Colleagues | 132 (25.0%) | 8 (7–9) | 7 (6–8) | 6 (5–8) | |||

| 214 (40.6%) | 7 (6–11) | 7 (6–9) | 5 (3–9) | ||||

| Telegram | 193 (36.6%) | 9 (8–12) | 8 (6–10) | 7 (5–12) | |||

| 174 (33.0%) | 7 (6–8) | 9 (7–10) | 6 (5–10) | ||||

| Lexi comp | 113 (21.4%) | 7 (5–13) | 9 (8–11) | 6 (4–9) | |||

| Drug Eye | 190 (36.1%) | 8 (6–8) | 9 (8–11) | 5 (4–8) | |||

| GeneBrandex | 51 (9.7%) | 7 (6–9) | 8 (7–9) | 6 (4–9) | |||

| Egyptian knowledge bank | 110 (20.9%) | 6 (5–8) | 10 (7–12) | 7 (5–9) | |||

| Guidelines | 135 (25.6%) | 11 (7–16) | 9 (8–11) | 7 (5–9) | |||

| Parameter | Total, n (%) |

|---|---|

| Side effects caused by PPIs | |

| Gastric carcinoids | 215 (40.8%) |

| Hip fractures | 179 (34.0%) |

| Hypomagnesemia | 214 (40.6%) |

| Nutritional deficiencies | 207 (39.3%) |

| Increased incidents of CVDs | 85 (16.1%) |

| Enteric infections | 141 (26.8%) |

| Diarrhea | 146 (27.7%) |

| Community-acquired pneumonia | 56 (10.6%) |

| Kidney diseases | 77 (14.6%) |

| Dementia | 102 (19.4%) |

| Change gut microbiota | 106 (20.1%) |

| Duodenal G-cell tumors | 81 (15.4%) |

| Anaphylaxis | 42 (8.0%) |

| Minerals and vitamins affected by PPIs | |

| Calcium | 270 (51.2%) |

| Magnesium | 253 (48.0%) |

| Vitamin B12 | 342 (64.9%) |

| Manganese | 106 (20.1%) |

| Potassium | 118 (22.4%) |

| Sodium | 91 (17.3%) |

| Selenium | 48 (9.1%) |

| Types of ulcers treated by PPIs | |

| NSAIDs-induced ulcer | 330 (62.6%) |

| Helicobacter pylori-induced ulcer | 314 (59.6%) |

| Stress ulcer prophylaxis | 210 (39.8%) |

| Drugs interact with PPIs | |

| Phenytoin | 290 (55.0%) |

| Warfarin | 278 (52.8%) |

| Clopidogrel | 266 (50.5%) |

| Atazanvir | 124 (23.5%) |

| Rilpivirine | 140 (26.6%) |

| Nelfinavir | 142 (26.9%) |

| Itraconazole | 152 (28.8%) |

| Ketoconazole | 176 (33.4%) |

| Posaconazole | 86 (16.3%) |

| What risk factors for ulcers and GI complications from NSAID use indicate the need for prophylactic PPIs? | |

| Use of warfarin | 194 (36.8%) |

| Use of anticoagulant | 180 (34.2%) |

| Use of dexamethasone | 176 (33.4%) |

| High-dose NSAIDs | 239 (45.4%) |

| Longer duration of NSAIDs | 231 (43.8%) |

| Low dose of aspirin | 125 (23.7%) |

| PPIs are clinically inferior to H2Ras, False | 254 (48.2%) |

| Which of the following is correct? | |

| All PPIs are OTC drugs. | 197 (37.4%) |

| All PPIs are prescription-only medicine. | 108 (20.5%) |

| Only some PPIs are OTC drugs. | 222 (42.1%) |

| The administration of PPIs with ticlopidine or clopidogrel or anti-coagulants alone without risk factors is recommended, False | 221 (41.9%) |

| In patients taking steroids alone for whatever clinical condition, mucosal protection with a PPI is routinely indicated, False | 142 (26.9%) |

| Sudden withdrawal of PPIs is not recommended, True | 300 (56.9%) |

| For which of the following categories of patients using NSAIDs and with no other risk factors are PPIs indicated for gastroprotection? | |

| 45–55 years | 214 (40.6%) |

| 56–65 years | 119 (22.6%) |

| >65 years | 194 (36.8%) |

| Esomeprazole, lansoprazole, and omeprazole work best when taken: | |

| 30 min before breakfast | 365 (69.3%) |

| After food | 130 (24.7%) |

| With food | 32 (6.1%) |

| What is the duration PPIs could be safely used without referring to a specialized physician? | |

| 2 weeks | 278 (52.8%) |

| 2 months | 107 (20.3%) |

| 3 months | 57 (10.8%) |

| Indefinitely | 85 (16.1%) |

| In case of persistent and severe night symptoms, it is recommended to: | |

| Take PPIs in the morning | 176 (33.4%) |

| Take PPIs before dinner | 180 (34.2%) |

| Fraction the daily dose into two separate administrations, one before breakfast and the other before dinner | 171 (32.4%) |

| PPI therapy should be prescribed to treat chronic laryngitis, False | 241 (45.7%) |

| PPIs can improve outcomes in Barrett’s esophagus, True | 311 (59.0%) |

| Like H2RA, PPIs can cause rapidly decreasing response to the drug (tachyphylaxis), False | 251 (47.6%) |

| Parameter | Total, n (%) |

|---|---|

| Provide advice for patients who use PPIs about lifestyle changes to alleviate their symptoms | |

| Always | 263 (49.9%) |

| Often | 125 (23.7%) |

| Sometimes | 90 (17.1%) |

| Rarely | 37 (7.0%) |

| Never | 12 (2.3%) |

| Contact the prescriber or advise the patient to stop PPIs when there is no current indication for their use | |

| Always | 164 (31.1%) |

| Often | 172 (32.6%) |

| Sometimes | 126 (23.9%) |

| Rarely | 46 (8.7%) |

| Never | 19 (3.6%) |

| Report ADR of PPIs to the manufacturer or regulatory authorities | |

| Always | 102 (19.4%) |

| Often | 127 (24.1%) |

| Sometimes | 129 (24.5%) |

| Rarely | 80 (15.2%) |

| Never | 89 (16.9%) |

| Consider PPIs the first choice when recommending acid-suppression drugs | |

| Always | 143 (27.1%) |

| Often | 154 (29.2%) |

| Sometimes | 148 (28.1%) |

| Rarely | 45 (7.0%) |

| Never | 37 (7.0%) |

| Prescribe PPI for patients, Yes | 450 (85.4%) |

| Use guidelines such as the JSGE or ACG when prescribing PPIs, Yes | 396 (75.1%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Moustafa, H.A.M.; Al Meslamani, A.Z.; Ahmed, H.M.M.E.; Ahmed, S.A.F.; Sallam, N.E.S.; Alshehri, G.H.; Alsubaie, N.; Kassem, A.B. Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices of Community Pharmacists Regarding Proton Pump Inhibitor (PPI) Use: A Cross-Sectional Study. Healthcare 2025, 13, 1588. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13131588

Moustafa HAM, Al Meslamani AZ, Ahmed HMME, Ahmed SAF, Sallam NES, Alshehri GH, Alsubaie N, Kassem AB. Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices of Community Pharmacists Regarding Proton Pump Inhibitor (PPI) Use: A Cross-Sectional Study. Healthcare. 2025; 13(13):1588. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13131588

Chicago/Turabian StyleMoustafa, Hebatallah Ahmed Mohamed, Ahmad Z. Al Meslamani, Hazem Mohamed Metwaly Elsayed Ahmed, Salma Ahmed Farouk Ahmed, Nada Ehab Shahin Sallam, Ghadah H. Alshehri, Nawal Alsubaie, and Amira B. Kassem. 2025. "Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices of Community Pharmacists Regarding Proton Pump Inhibitor (PPI) Use: A Cross-Sectional Study" Healthcare 13, no. 13: 1588. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13131588

APA StyleMoustafa, H. A. M., Al Meslamani, A. Z., Ahmed, H. M. M. E., Ahmed, S. A. F., Sallam, N. E. S., Alshehri, G. H., Alsubaie, N., & Kassem, A. B. (2025). Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices of Community Pharmacists Regarding Proton Pump Inhibitor (PPI) Use: A Cross-Sectional Study. Healthcare, 13(13), 1588. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13131588