Psychosocial Determinants of Childbirth Fear Among Asian Women: A Scoping Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

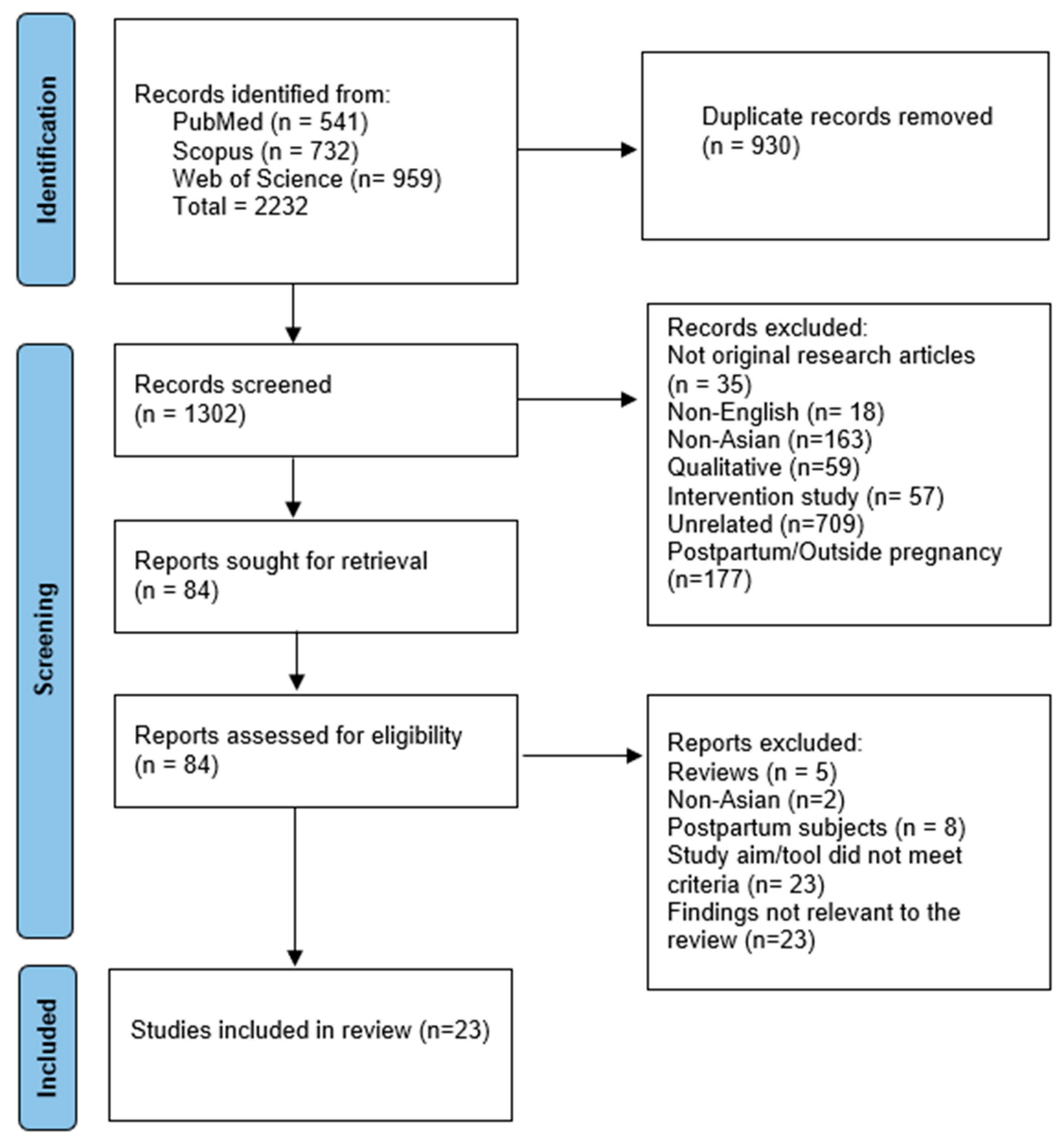

2. Materials and Methods

- (1)

- Studies were conducted in Asian countries;

- (2)

- Fear of childbirth was studied as the primary outcome;

- (3)

- Maternal childbirth fear was assessed antenatally;

- (4)

- FOC was measured using a validated scale, not as a subdomain of a larger instrument.

- (1)

- Letters or commentary, conference abstracts, editorial, and book chapters;

- (2)

- Studies conducted postpartum;

- (3)

- Qualitative or interventional studies.

3. Results

3.1. Psychiatric Symptoms/Disorder

3.2. Psychological Determinants

3.3. Perception, Experience & Spirituality

3.4. Support and Relationship

3.5. COVID-19 Pandemic

4. Discussion

4.1. Clinical Implications

4.2. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| FOC | fear of childbirth |

| WDEQ-A | Wijma Delivery Expectancy Questionnaire Part A |

| CAQ | Childbirth Attitude Questionnaire |

| IU | intolerance to uncertainty |

| IPV | intimate partner violence |

Appendix A

| JBI Critical Appraisal Checklists for Cross-Sectional Studies | Abdollahpour, 2018 [24] | Aksoy, 2023 [25] | Anjum, 2022 [26] | Barat, 2023 [27] | Bilgic, 2021 [28] | Citak, 2021 [17] | Eroglu, 2022 [29] | Gao, 2015 [30] | Han, 2022 [31] | Hou, 2022 [32] | Huang, 2021 [33] | Korucku, 2019 [34] | Marcelina, 2019 [35] | Moghaddam Hossieni, 2017 [36] | Mohamadirizi, 2017 [37] | Nguyen, 2021 [38] | Qiu, 2019 [39] | Takegata, 2014 [40] | Tiryaki, 2022 [41] | Ulu, 2022 [42] | Yildrim, 2023 [43] | Zhang, 2023 [44] | Zhou, 2021 [45] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Were the criteria for inclusion in the sample clearly defined? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | NC | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Were the study subjects and the setting described in detail? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | NC | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | NC | NC | NC | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | NC | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Was the exposure measured in a valid and reliable way? | Yes | Yes | NC | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Were objective, standard criteria used for measurement of the condition? | Yes | Yes | NC | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | NC | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Were the confounding factors identified? | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | NC | NC | Yes | NC | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Were strategies to deal with confounding factors stated? | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | NC | NC | Yes | NC | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Were the outcomes measured in a valid and reliable way? | Yes | Yes | NC | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | NC | Yes | NC | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Was appropriate statistical analysis used? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Total Quality Assessment Score for each study (based on six criteria) | 75% High | 100% High | 38% Med | 100% High | 75% High | 100% High | 88% High | 100% High | 100% High | 100% High | 100% High | 75% High | 50% Med | 88% High | 50% Med | 100% High | 100% High | 100% High | 75% High | 38% Med | 100% High | 100% High | 100% High |

| No | Author, Year | Study Population Background Risk | FOC Tool | FOC Threshold Score | Conclusion/Recommendations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Abdollahpour, 2018 [24] | Low-risk, no psychiatric diagnosis | CAQ | FOC > 32 | Increasing the level of spiritual intelligence in pregnant women can lead to an increase in their happiness and reduce FOC. FOC can be prevented via maternal training about the components of spiritual intelligence. |

| 2 | Aksoy, 2023 [25] | High-risk pregnancy | FOBS | FOC > 50 | Women with high-risk pregnancies may experience COVID-19 anxiety, which may worsen FOC. Psychosocial interventions focusing on COVID-19 anxiety are warranted for these women. |

| 3 | Anjum, 2022 [26] | Low-risk | WDEQ-A | NS | Partner support is essential to overcome FOC and help increase the well-being of first-time pregnant women. |

| 4 | Barat, 2023 [27] | Women with CS indications excluded | WDEQ | FOC > 85 | It is necessary to design a comprehensive antenatal training program to reduce FOC among women with risk factors, i.e., having an academic education, a self-employed spouse, a history of infertility, and psychiatric illness. |

| 5 | Bilgic, 2021 [28] | Low-risk, no psychiatric diagnosis | WDEQ-A Turkish | High: 66–84 Clinical > 85 | There was a negative correlation between psychological (PWB) and spiritual well-being (SWB) and FOC. SWB was a partial mediating variable in PWB and FOC relationship. PWB and SWB of pregnant women should be evaluated in order to reduce FOC. |

| 6 | Citak, 2021 [17] | Low-risk, no psychiatric diagnosis | WDEQ-A Turkish | Severe > 85 | The psychosocial variables predicting FOC were self-efficacy and trait anxiety. Spousal support is a mediator between self-efficacy and FOC. Individualized education programs and delivery preparation training, based on maternal psychosocial needs, may lead to better coping with FOC. |

| 7 | Eroglu, 2022 [29] | No previous CS | WDEQ-A Turkish | High: 66–84 Severe > 85 | Depression and anxiety level, educational level, access to information on delivery during pregnancy, presence of medical disease, and expression of FOC were predictors of high/severe FOC. Pregnant women with high/severe FOC also had a significantly higher vaginismus score. Assessment of FOC and associated risk factors, including vaginismus, during pregnancy, will enable the identification of risk groups and the creation of support programs. |

| 8 | Gao, 2015 [30] | Low-risk, no previous CS | CAQ Chinese | NS | State-anxiety, trait-anxiety, age, and previous miscarriage were predictors of childbirth fear among pregnant Chinese women. The health-care professionals should be sensitive toward childbirth fear and assess pregnant women’s age, educational level, and previous miscarriage to identify the pregnant women who may have severe childbirth fear. |

| 9 | Han, 2022 [31] | Low-risk, no psychiatric diagnosis | CAQ Chinese | FOC > 28 Moderate: 40–51 Severe: 52–64 | Primiparas, unplanned pregnancy, few spousal supports, intolerance of uncertainty, and negative coping styles were significant risk factors in FOC. Regular screening assessment of perinatal psychological symptoms, such as a high level of intolerance of uncertainty and negative coping styles, should be adopted to reduce the risk of FOC. |

| 10 | Hou, 2022 [32] | Low-risk, no psychiatric diagnosis | CAQ Chinese | NS | The number of CSs, experience with previous CS, childbirth self-efficacy, and social support were predictors of FOC among re-pregnant women after CS in China. Healthcare professionals need to identify these women with high-risk of FOC and provide appropriate services during pregnancy. |

| 11 | Huang, 2021 [33] | Low-risk, no previous CS, no psychiatric diagnosis | CAQ Chinese | NS | Age, gestational age, parity, spousal support, resilience, and childbirth self-efficacy were predictors of FOC. Healthcare professionals should pay close attention to FOC and implement targeted interventions in accordance with these predictors, especially resilience and childbirth self-efficacy |

| 12 | Korukcu, 2019 [34] | Low-risk, no psychiatric or chronic disease | WDEQ-A | Moderate 61–84 Severe ≥ 85 | Counterintuitively, there is a negative relationship between the previous birth experience and childbirth fear. Childbirth fear can persist through the postpartum period, and health care professionals need to address FOC through sensitive discussions with women about the birthing experience and their thoughts concerning future births. |

| 13 | Marcelina, 2019 [35] | NS | WDEQ-A | NS | Satisfaction with the husband’s support and maternal anxiety were important predictors of childbirth fear. It is recommended for health care providers to facilitate husbands throughout antenatal care to support their wives in preventing FOC. |

| 14 | Moghaddam Hossieni, 2017 [36] | Low-risk, no psychiatric diagnosis | rFDQ | Severe fear ≥ 6 | All pregnant women experiencing physical violence had a higher chance of FOC. Screening programs for FOC and intimate partner violence (IPV) need to be implemented particularly in nulliparous women. Providing continuity of midwifery care and family therapy may be strategies for early support to reduce IPV to pregnant women. |

| 15 | Mohamadirizi, 2017 [37] | Low-risk, no medical/psychiatric diagnosis | CAQ | NS | High spiritual intelligence in pregnant women can reduce the fear of childbirth. |

| 16 | Nguyen, 2021 [38] | Low-risk, no chronic condition or fetal loss | FOBS | NS | FOC was associated with age of partner; previous pregnancy complications; attitudes toward different aspects of childbirth delivery; satisfactions with friends, parents, and siblings’ care; and information support. Individualized psychological counseling and information-seeking guidance should be provided appropriately for multiparous and nulliparous women to reduce fear and improve the acceptability of the prevention services. |

| 17 | Qiu, 2019 [39] | NS | CAQ Chinese | NS | Education levels, self-rated health status, self-efficacy levels, and use of pregnancy-related smartphone applications were predictors of FOC among pregnant women in China. Healthcare professionals should focus on the above factors in identifying pregnant women with FOC and implementing targeted interventions. |

| 18 | Takegata, 2014 [40] | Low-risk, not planning CS | WDEQ-A Japanese | Severe: 85–99 Phobia > 100 | Sense of coherence (SOC) was negatively linked with antenatal FOC. High SOC works as a resiliency factor that helps pregnant women cope with the stress of their upcoming childbirth and reduces FOC. |

| 19 | Tiryaki, 2022 [41] | High-risk (maternal and fetal), no psychiatric diagnosis | FOBS | FOC ≥ 50 | Prenatal anxiety was prevalent among high-risk pregnant women who required routine anxiety screening and psychosocial support during the COVID-19 pandemic. |

| 20 | Ulu, 2022 [42] | Unspecified | WDEQ-A | NS | Fear of childbirth was positively correlated to fear of COVID-19 and negatively correlated to marital adjustment. Psychological support to pregnant women is beneficial to reduce their fears and to improve marital adjustment by including the spouses in the process. |

| 21 | Yildrim, 2023 [43] | Low-risk, no previous CS | WDEQ-A | NS | Lack of prenatal education, inability to cope with childbirth, and depression and anxiety were significant predictors of FOC. Health professionals can provide individualized care, education, and counseling services by taking into account the effects of depression and anxiety so that expectant women’s fear of childbirth can be reduced. |

| 22 | Zhang, 2023 [44] | No psychiatric disorder | CAQ Chinese | FOC ≥ 28 Moderate: 40–51 Severe: 52–64 | Significant FOC risk factors were prolonged exposure to electronic screens, nullipara, previous CS, preference to sour food or dislike greasy food, worrying about delivery without family members, family function, doctor-patient communication, anxiety, and depression. There is an urgent need to develop interventions to reduce FOC in the third trimester of pregnancy, with particular attention to those with risk factors. |

| 23 | Zhou, 2021 [45] | Low-risk, no psychiatric diagnosis | CAQ | FOC ≥ 28 Moderate: 40–51 Severe: 52–64 | FOC showed a positive correlation with pregnancy-related stress and depressive symptoms and a negative correlation with social support. Screening for FOC and helping pregnant women identify a support system early in pregnancy could reduce a woman’s stress level and the severity of depression. |

References

- Larkin, P.; Begley, C.M.; Devane, D. Women’s experiences of labour and birth: An evolutionary concept analysis. Midwifery 2009, 25, e49–e59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melender, H.L. Experiences of fears associated with pregnancy and childbirth: A study of 329 pregnant women. Birth 2002, 29, 101–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demšar, K.; Svetina, M.; Verdenik, I.; Tul, N.; Blickstein, I.; Globevnik Velikonja, V. Tokophobia (fear of childbirth): Prevalence and risk factors. J. Perinat. Med. 2018, 46, 151–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richens, Y.; Smith, D.M.; Lavender, D.T. Fear of birth in clinical practice: A structured review of current measurement tools. Sex. Reprod. Healthc. 2018, 16, 98–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Connell, M.A.; Leahy-Warren, P.; Khashan, A.S.; Kenny, L.C.; O’Neill, S.M. Worldwide prevalence of tocophobia in pregnant women: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2017, 96, 907–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nilsson, C.; Hessman, E.; Sjöblom, H.; Dencker, A.; Jangsten, E.; Mollberg, M.; Patel, H.; Sparud-Lundin, C.; Wigert, H.; Begley, C. Definitions, measurements and prevalence of fear of childbirth: A systematic review. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2018, 18, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dencker, A.; Nilsson, C.; Begley, C.; Jangsten, E.; Mollberg, M.; Patel, H.; Wigert, H.; Hessman, E.; Sjöblom, H.; Sparud-Lundin, C. Causes and outcomes in studies of fear of childbirth: A systematic review. Women Birth 2019, 32, 99–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Striebich, S.; Mattern, E.; Ayerle, G.M. Support for pregnant women identified with fear of childbirth (FOC)/tokophobia—A systematic review of approaches and interventions. Midwifery 2018, 61, 97–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haines, H.M.; Pallant, J.F.; Fenwick, J.; Gamble, J.; Creedy, D.K.; Toohill, J.; Hildingsson, I. Identifying women who are afraid of giving birth: A comparison of the fear of birth scale with the WDEQ-A in a large Australian cohort. Sex. Reprod. Healthc. 2015, 6, 204–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega-Cejas, C.M.; Roldán-Merino, J.; Lluch-Canut, T.; Castrillo-Pérez, M.I.; Vicente-Hernández, M.M.; Jimenez-Barragan, M.; Biurrun-Garrido, A.; Farres-Tarafa, M.; Casas, I.; Cabrera-Jaime, S. Reliability and validity study of the Spanish adaptation of the “Wijma Delivery Expectancy/Experience Questionnaire” (W-DEQ-A). PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0248595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayers, S. Fear of childbirth, postnatal post-traumatic stress disorder and midwifery care. Midwifery 2014, 30, 145–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Çapik, A.; Durmaz, H. Fear of Childbirth, Postpartum Depression, and Birth-Related Variables as Predictors of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder After Childbirth. Worldviews Evid. Based Nurs. 2018, 15, 455–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taheri, M.; Takian, A.; Taghizadeh, Z.; Jafari, N.; Sarafraz, N. Creating a positive perception of childbirth experience: Systematic review and meta-analysis of prenatal and intrapartum interventions. Reprod. Health 2018, 15, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pang, M.W.; Leung, T.N.; Lau, T.K.; Hang Chung, T.K. Impact of first childbirth on changes in women’s preference for mode of delivery: Follow-up of a longitudinal observational study. Birth 2008, 35, 121–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takegata, M.; Haruna, M.; Morikawa, M.; Yonezawa, K.; Komada, M.; Severinsson, E. Qualitative exploration of fear of childbirth and preferences for mode of birth among Japanese primiparas. Nurs. Health Sci. 2018, 20, 338–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin-Lewry, M.; Tu, H.R.; Au, H.K.; Nguyen, C.T.T.; Lee, G.T.; Kuo, S.Y. Psychometric evaluation of the wijma delivery expectancy/experience questionnaire for pregnant women in Taiwan. Midwifery 2025, 140, 104207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çıtak Bilgin, N.; Coşkun, H.; Coşkuner Potur, D.; İbar Aydın, E.; Uca, E. Psychosocial predictors of the fear of childbirth in Turkish pregnant women. J. Psychosom. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2021, 42, 123–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munn, Z.; Peters, M.D.J.; Stern, C.; Tufanaru, C.; McArthur, A.; Aromataris, E. Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2018, 18, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arksey, H.; O’malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moola, S.; Munn, Z.; Tufanaru, C.; Aromataris, E.; Sears, K.; Sfetcu, R.; Currie, M.; Qureshi, R.; Mattis, P.; Lisy, K. Systematic reviews of etiology and risk. Joanna Briggs Inst. Rev. Man. 2017, 5, 217–269. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Qahtani, S.; Jalal, Z.; Paudyal, V.; Mahmood, S.; Mason, J. The Role of Pharmacists in Providing Pharmaceutical Care in Primary and Secondary Prevention of Stroke: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Healthcare 2022, 10, 2315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalok, A.; Kamisan Atan, I.; Sharip, S.; Safian, N.; Shah, S.A. Factors influencing childbirth fear among Asian women: A scoping review. Front. Public Health 2024, 12, 1448940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdollahpour, S.; Khosravi, A. Relationship between Spiritual Intelligence with Happiness and Fear of Childbirth in Iranian Pregnant Women. Iran. J. Nurs. Midwifery Res. 2018, 23, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aksoy, S.D.; Ozdemir, S.; Akbal, E. Effects of COVID-19 anxiety and obsession on fear of childbirth in high-risk pregnancy during the pandemic in Turkey. Int. J. Psychiatry Med. 2023, 58, 476–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anjum, A.; Mushtaq, M.; Anwar, T.; Ali, M. Fear of Childbirth: Well-being and Partner Support in First-time Pregnant Women. J. Liaquat Univ. Med. Health Sci. 2023, 22, 55–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barat, S.; Kordinejad, B.; Faramarzi, M.; Khafri, S.; Bouzari, Z.; Ebrahim, E. Prevalence of Fear of Childbirth and its Effective Factors in Pregnant Women in Babol, Iran (2019–2020): A Cross-sectional Study. Int. J. Women’s Health Reprod. Sci. 2023, 11, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilgic, G.; Bilgin, N.C. Relationship Between Fear of Childbirth and Psychological and Spiritual Well-Being in Pregnant Women. J. Relig. Health 2021, 60, 295–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eroglu, E.O.; Yildiz, M.I.; Turkoglu, O.; Tanriover, E.; Evran, A.; Karahan, S.; Sahin, D. High/severe fear of childbirth and related risk factors among pregnant women: Is vaginismus a risk factor? J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2022, 42, 2860–2866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.L.; Liu, X.J.; Fu, B.L.; Xie, W. Predictors of childbirth fear among pregnant Chinese women: A cross-sectional questionnaire survey. Midwifery 2015, 31, 865–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, L.; Bai, H.; Lun, B.; Li, Y.; Wang, Y.; Ni, Q. The Prevalence of Fear of Childbirth and Its Association With Intolerance of Uncertainty and Coping Styles Among Pregnant Chinese Women During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 935760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, Y.; Zhou, X.; Yao, M.; Liu, S. Fear of childbirth and its predictors in re-pregnant women after cesarean section: A cross-sectional multicenter study in China. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2022, 22, 393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Huang, J.; Li, Y.; Liao, B. The prevalence and predictors of fear of childbirth among pregnant Chinese women: A hierarchical regression analysis. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2021, 21, 643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korukcu, O.; Bulut, O.; Kukulu, K. From experiences to expectations: A quantitative study on the fear of childbirth among multigravida women. Arch. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2019, 33, 248–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcelina, L.A.; Rachmawati, I.N.; Ungsianik, T. Dissatisfaction with the husband support increases childbirth fear among Indonesian primigravida. Enferm. Clin. 2019, 29, 379–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moghaddam Hossieni, V.; Toohill, J.; Akaberi, A.; HashemiAsl, B. Influence of intimate partner violence during pregnancy on fear of childbirth. Sex. Reprod. Healthc. 2017, 14, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohamadirizi, M.; Mohebbi Dehnavi, Z.; Torabi, F.; Mohamadirizi, S. The relationship between spiritual intelligence and fear of childbirth in low-risk pregnant women. J. Babol Univ. Med. Sci. 2017, 19, 26–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, L.D.; Nguyen, L.H.; Ninh, L.T.; Nguyen, H.T.T.; Nguyen, A.D.; Vu, L.G.; Nguyen, C.T.; Vu, G.T.; Doan, L.P.; Latkin, C.A.; et al. Fear of Childbirth and Preferences for Prevention Services among Urban Pregnant Women in a Developing Country: A Multicenter, Cross-Sectional Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, L.; Sun, N.; Shi, X.; Zhao, Y.; Feng, L.; Gong, Y.; Yin, X. Fear of childbirth in nulliparous women: A cross-sectional multicentre study in China. Women Birth 2020, 33, e136–e141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takegata, M.; Haruna, M.; Matsuzaki, M.; Shiraishi, M.; Okano, T.; Severinsson, E. Antenatal fear of childbirth and sense of coherence among healthy pregnant women in Japan: A cross-sectional study. Arch. Womens Ment. Health 2014, 17, 403–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiryaki, O.; Zengin, H.; Gok, K.; Bostanci, M.S.; Ozden, S. Concerns of High-Risk Pregnancies During Pandemic: COVID-19 and Fear of Birth. Florence Nightingale J. Nurs. 2022, 30, 274–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ulu, E.; Ertunç, T. Being pregnant in Covid-19: Fear of Giving Birth, Fear of Covid-19, and Marital Adjustment. Cyprus Turk. J. Psychiatry Psychol. 2022, 4, 222–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yıldırım, A.; Alp Yılmaz, F. Effects of depression and anxiety on the fear of childbirth. Curr. Psychol. 2023, 43, 7691–7696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Liu, M.; Min, F.; Wei, W.; Liu, Y.; Tong, J.; Meng, Q.; Sun, L.; Chen, X. Fear of childbirth and its determinants in pregnant women in the third trimester: A cross-sectional study. BMC Psychiatry 2023, 23, 574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Liu, H.; Li, X.; Zhang, S. Fear of Childbirth and Associated Risk Factors in Healthy Pregnant Women in Northwest of China: A Cross-Sectional Study. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2021, 14, 731–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; McAra-Couper, J.; Lou, Y.; Guo, S.; Qiu, P. Validation of the Chinese version of the Fear of Birth Scale among pregnant women. Midwifery 2024, 133, 103986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.L.; Wei, Y.R.; Cao, G.F.; Zhang, S.M.; Yang, L.; Li, X.M. Comparison of the W-DEQ and CAQ in assessing FOC among pregnant women in China. J. Psychosom. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2025, 46, 2469178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanjari, S.; Chaman, R.; Salehin, S.; Goli, S.; Keramat, A. Update on the Global Prevalence of Severe Fear of Childbirth in Low-Risk Pregnant Women: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Women’s Health Reprod. Sci. 2022, 10, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phunyammalee, M.; Buayaem, T.; Boriboonhirunsarn, D. Fear of childbirth and associated factors among low-risk pregnant women. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2019, 39, 763–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouhe, H.; Salmela-Aro, K.; Gissler, M.; Halmesmäki, E.; Saisto, T. Mental health problems common in women with fear of childbirth. Bjog 2011, 118, 1104–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Söderquist, J.; Wijma, K.; Wijma, B. Traumatic stress in late pregnancy. J. Anxiety Disord. 2004, 18, 127–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laursen, M.; Hedegaard, M.; Johansen, C. Fear of childbirth: Predictors and temporal changes among nulliparous women in the Danish National Birth Cohort. Bjog 2008, 115, 354–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lukasse, M.; Schei, B.; Ryding, E.L. Prevalence and associated factors of fear of childbirth in six European countries. Sex. Reprod. Healthc. 2014, 5, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Räisänen, S.; Lehto, S.M.; Nielsen, H.S.; Gissler, M.; Kramer, M.R.; Heinonen, S. Fear of childbirth in nulliparous and multiparous women: A population-based analysis of all singleton births in Finland in 1997-2010. Bjog 2014, 121, 965–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Storksen, H.T.; Eberhard-Gran, M.; Garthus-Niegel, S.; Eskild, A. Fear of childbirth; the relation to anxiety and depression. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2012, 91, 237–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saisto, T.; Halmesmäki, E. Fear of childbirth: A neglected dilemma. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2003, 82, 201–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, J.; Heron, J.; Francomb, H.; Oke, S.; Golding, J. Cohort study of depressed mood during pregnancy and after childbirth. Bmj 2001, 323, 257–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Self-efficacy mechanism in human agency. Am. Psychol. 1982, 37, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowe, N.K. Self-efficacy for labor and childbirth fears in nulliparous pregnant women. J. Psychosom. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2000, 21, 219–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salomonsson, B.; Gullberg, M.T.; Alehagen, S.; Wijma, K. Self-efficacy beliefs and fear of childbirth in nulliparous women. J. Psychosom. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2013, 34, 116–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, L.; Toohill, J.; Creedy, D.K.; Baird, K.; Gamble, J.; Fenwick, J. Factors associated with childbirth self-efficacy in Australian childbearing women. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2015, 15, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarus, R.S.; Folkman, S. Stress, Appraisal, and Coping; Springer Publishing Company: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Daglar, G.; Bilgic, D.; Cakir, D. The correlation between levels of prenatal attachment and styles coping with stress in pregnant women. J. Reprod. Infant. Psychol. 2022, 40, 254–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rondung, E.; Ekdahl, J.; Sundin, Ö. Potential mechanisms in fear of birth: The role of pain catastrophizing and intolerance of uncertainty. Birth 2019, 46, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowold, J. Effects of Spiritual Well-Being on Subsequent Happiness, Psychological Well-Being, and Stress. J. Relig. Health 2011, 50, 950–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fagbenro, D.A.; Folasade, A.O. Influence of stages of pregnancy on the psychological well-being of pregnant women in Ibadan, Nigeria. Int. J. Caring Sci. 2018, 11, 719–724. [Google Scholar]

- Hosaini, S.; Yazdkhasti, M.; Moafi Ghafari, F.; Mohamadi, F.; Kamran Rad, S.H.R.; Mahmoodi, Z. The relationships of spiritual health, pregnancy worries and stress and perceived social support with childbirth fear and experience: A path analysis. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0294910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dehestani, H.; Moshfeghy, Z.; Ghodrati, F.; Akbarzadeh, M. The relationship of spiritual health and mother’s forgiveness with her anxiety in the labor of the pregnant women. Int. J. Women’s Health Reprod. Sci. 2019, 7, 174–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amirian, M.E.; Fazilat-Pour, M. Simple and Multivariate Relationships Between Spiritual Intelligence with General Health and Happiness. J. Relig. Health 2016, 55, 1275–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsson, C.; Bondas, T.; Lundgren, I. Previous birth experience in women with intense fear of childbirth. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Neonatal Nurs. 2010, 39, 298–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Størksen, H.T.; Garthus-Niegel, S.; Vangen, S.; Eberhard-Gran, M. The impact of previous birth experiences on maternal fear of childbirth. Acta Obstet. Et Gynecol. Scand. 2013, 92, 318–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korukcu, O.; Bulut, O.; Kukulu, K. Psychometric Evaluation of the Wijma Delivery Expectancy/Experience Questionnaire Version B. Health Care Women Int. 2016, 37, 550–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elvander, C.; Cnattingius, S.; Kjerulff, K.H. Birth experience in women with low, intermediate or high levels of fear: Findings from the first baby study. Birth 2013, 40, 289–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, H.J.; Song, J.E.; Lee, Y.; Ahn, J.A. [Effects of stress, depression, and spousal and familial support on maternal identity in pregnant women]. Korean J. Women Health Nurs. 2020, 26, 84–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogurlu, M.; Erbil, N. The Effect of Intimate Partner Violence on Fear of Childbirth Among Pregnant Women. J. Interpers. Violence 2023, 38, 3737–3755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eberhard-Gran, M.; Slinning, K.; Eskild, A. Fear during labor: The impact of sexual abuse in adult life. J. Psychosom. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2008, 29, 258–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, C.; Hauck, Y.; Fenwick, J. How social context impacts on women’s fears of childbirth: A Western Australian example. Soc. Sci. Med. 2006, 63, 64–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doaltabadi, Z.; Amiri-Farahani, L.; Hasanpoor-Azghady, S.B.; Haghani, S. The effect of face-to-face and virtual prenatal care training of spouses on the pregnancy experience and fear of childbirth of primiparous women: A controlled quasi-experimental study. J. Telemed. Telecare 2021, 29, 775–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, X.L.; Liu, H.; Li, X.H.; Li, F.; Zhang, S.M.; Zhang, S.R. Mediating effects of social support between antenatal depression and fear of childbirth among nulliparous woman. Ann. Palliat. Med. 2021, 10, 6399–6409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mortazavi, F.; Mehrabadi, M.; KiaeeTabar, R. Pregnant women’s well-being and worry during the COVID-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2021, 21, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moyer, C.A.; Compton, S.D.; Kaselitz, E.; Muzik, M. Pregnancy-related anxiety during COVID-19: A nationwide survey of 2740 pregnant women. Arch. Womens Ment. Health 2020, 23, 757–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wastnedge, E.A.N.; Reynolds, R.M.; van Boeckel, S.R.; Stock, S.J.; Denison, F.C.; Maybin, J.A.; Critchley, H.O.D. Pregnancy and COVID-19. Physiol. Rev. 2021, 101, 303–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stainback, K.; Hearne, B.N.; Trieu, M.M. COVID-19 and the 24/7 news cycle: Does COVID-19 news exposure affect mental health? Socius 2020, 6, 2378023120969339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Rosa, V.L.; Alparone, D.; Commodari, E. Psychological and social factors influencing mother-child bonding in the first year after birth: A model for promoting infant and maternal well-being. Front. Psychol. 2025, 16, 1588433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdelghaffar, W.; Daoud, M.; Philip, S.; Ransing, R.; Jamir, L.; Jatchavala, C.; Pinto da Costa, M. Perinatal mental health programs in low and middle-income countries: India, Thailand, and Tunisia. Asian J. Psychiatr. 2023, 88, 103706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jatchavala, C.; Philip, S.; Malakar, H.; Rongmei, L.; Devraj, N.; Ransing, R. Perinatal mental health in India and Thailand: A call for collaboration. J. Taibah Univ. Med. Sci. 2023, 18, 1373–1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No | Author | Year | Country | Study Aim: To Investigate | Gestation in Weeks; Parity (Special Risk) | Total Number (N) | FOC Assessment Tool | FOC Prevalence (Level) | Other Assessment Tools |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Abdollahpour [24] | 2018 | Iran | The relationship between spiritual intelligence and happiness and FOC | 20–34; all | 245 | CAQ | NA | SISRI; OHQ |

| 2 | Aksoy [25] | 2023 | Turkey | The relationship between COVID-19 obsession and anxiety and FOC in high-risk pregnancies | ≥20; all (high-risk women) | 326 | FOBS | NA | CAS; OCS |

| 3 | Anjum [26] | 2022 | Pakistan | The relationship among women’s fear of childbirth, well-being, and partner support | >35; nullip | 100 | WDEQ-A | NA | Partner Support Questionnaire; Well-being in Pregnant Women Questionnaire |

| 4 | Barat [27] | 2023 | Iran | To screen for FOC and associated factors | ≥20; all | 600 | WDEQ | 29.2% Severe | PPRQ; Pregnancy History; Body Image Questionnaire; Pelvic Injury Questionnaire |

| 5 | Bilgic [28] | 2021 | Turkey | The relationship between FOC and psychological and spiritual well-being | Any; all | 338 | WDEQ-A Turkish | 70.1% Overall 19.8% High 13.9% Clinical | PWBS; SWBS |

| 6 | Citak [17] | 2021 | Turkey | The psychosocial predictors of FOC in pregnant women | ≥28; all | 624 | WDEQ-A Turkish | 20.8% Severe | CBSIE-Short Form; MPSS; STAI-T; PSEQ-Relationship with husband |

| 7 | Eroglu [29] | 2022 | Turkey | The prevalence of FOC and associated factors, including vaginismus, in pregnant women with high/severe FOC | 24–40; all | 407 | WDEQ-A Turkish | 82.1% Overall 32.2% High 13.8% Severe | BDI; BAI; GRISS-vaginismus subscale |

| 8 | Gao [30] | 2015 | China | FOC and its predictors among Chinese women | ≥28; all | 353 | CAQ Chinese | NA | STAI; CBSEI (Chinese) |

| 9 | Han [31] | 2022 | China | The associations between coping styles, intolerance of uncertainty, and FOC | 24–40; all | 969 | CAQ Chinese | 67.8% Overall | IUS-12; SCSQ |

| 10 | Hou [32] | 2022 | China | FOC and its predictors in re-pregnant women after caesarean section | ≥28; all | 358 | CAQ Chinese | NA | CBSEI-32 (Chinese); SSRS |

| 11 | Huang [33] | 2021 | China | The prevalence and predictors of FOC among Chinese women | ≥11; all | 646 | CAQ Chinese | NA | CBSEI-32; CD-RISC-10 |

| 12 | Korukcu [34] | 2019 | Turkey | The effects of previous birth experience(s) on the FOC in the current pregnancy | 28–40; multip | 309 | WDEQ-A | 69.6% Overall 19.1% Severe | Past pregnancy experience: happily/proudly/in pain/fear |

| 13 | Marcelina [35] | 2019 | Indonesia | The predictors of childbirth fear among Indonesian primigravida | ≥28; nullip | 126 | WDEQ-A | 45.2% Severe | MAT; PSS; PRAQ-R2 |

| 14 | Moghaddam Hossieni [36] | 2017 | Iran | The prevalence of intimate partner violence (IPV) and its prediction of FOC | ≥14; all | 174 | rFDQ | 61.5% Overall | CTS2; STAI |

| 15 | Mohamadirizi [37] | 2017 | Iran | The relationship between spiritual intelligence and fear of delivery in low–risk women | ≥28; nullip | 220 | CAQ | NA | Spiritual Intelligence Self-Report Inventory |

| 16 | Nguyen [38] | 2021 | Vietnam | The FOC and willingness to pay for fear-prevention services in pregnant women | ns; all | 900 | FOBS | NA | MSPSS; Concerns about physical changes; PICSS |

| 17 | Qiu [39] | 2019 | China | The status of FOC and its associated factors among nulliparous women in China | ns; all | 1039 | CAQ Chinese | NA | Modified General Perceived Self-Efficacy Scale |

| 18 | Takegata [40] | 2014 | Japan | The relationship between FOC and sense of coherence (SOC) | 37; all | 226 | WDEQ-A Japanese | NA | SOC |

| 19 | Tiryaki [41] | 2022 | Turkey | The fear of birth and COVID-19 in high-risk pregnant women | 20–40; all (high-risk women) | 238 | FOBS | NA | FCV-19S |

| 20 | Ulu [42] | 2022 | Turkey | The relationship between fear of childbirth, fear of COVID-19, and marital adjustment | ns; all | 382 | WDEQ-A | NA | Fear of COVID-19 Scale; RDAS |

| 21 | Yildrim [43] | 2023 | Turkey | The influences of anxiety and depression on FOC | ≥ 28; all | 501 | WDEQ-A | 72.7% Overall 46.0% Moderate | BDI; BAI |

| 22 | Zhang [44] | 2023 | China | The prevalence and risk factors of FOC among pregnant women in the third trimester of pregnancy | ≥28; all | 535 | CAQ Chinese | 56.6% Overall 3.9% Severe | APGAR; CAHPS; Oslo 3-item social support scale; GSES; GAD-7; PHQ-9, ISI; WHOQOL-8 |

| 23 | Zhou [45] | 2021 | China | The prevalence and risk factors for fear of childbirth | 14–41; all | 922 | CAQ | 70.3% Overall 6.0% Severe | MSPSS, EPDS, PPS |

| 10,538 |

| Factors | Independent Factors | Studies |

|---|---|---|

| Psychiatric Symptoms/Disorder | ||

| Psychiatric disorder | History of psychiatric disorder (AOR 6.86, p = 0.020) | Barat 2023 [27] |

| Depression | Depression score (β = 0.441, p < 0.001) | Yildrim 2023 [43] |

| Depressive symptoms (β = 0.220, p < 0.001) | Zhou 2021 [45] | |

| Depression (AOR 1.11, p < 0.001) | Eroglu 2022 [29] | |

| Depression (β = 0.30, p = 0.027) | Zhang 2023 [44] | |

| Anxiety | State-anxiety (β = 0.24, p = 0.002), Trait-anxiety (β = 0.27, p = 0.001) | Gao 2015 [30] |

| Anxiety (β = 0.239, p < 0.001) | Yildrim 2023 [43] | |

| Trait-anxiety (β = 0.287, p < 0.001) | Citak 2021 [17] | |

| Anxiety (AOR 1.03, p = 0.045) | Eroglu 2022 [29] | |

| Anxiety (β = 0.50, p = 0.001) | Zhang 2023 [44] | |

| Childbirth-related anxiety (AOR 3.37, p = 0.005) | Marcelina 2019 [35] | |

| Stress | Pregnancy stress (β = 0.394, p < 0.001) | Zhou 2021 [45] |

| Psychological Determinants | ||

| Childbirth Self-efficacy | Childbirth self-efficacy (β = −0.790, p < 0.001) | Qiu 2019 [39] |

| Childbirth self-efficacy (β = −0.495, p < 0.001) | Huang 2021 [33] | |

| Childbirth self-efficacy (β = −0.463, p < 0.001) | Citak 2021 [17] | |

| Childbirth self-efficacy (β = −1.284, p < 0.001) | Hou 2022 [32] | |

| Psychological well-being | Psychological well-being (β = −0.273, p < 0.001) | Bilgic 2021 [28] |

| Maternal coping | Coping with childbirth (β = −0.088, p = 0.041) | Yildrim 2023 [43] |

| Negative coping style (β = 0.261, p < 0.001); Positive coping style (β = −0.135, p < 0.001); | Han 2022 [31] | |

| Resilience | Maternal resilience (β = −0.305, p < 0.001) | Huang 2021 [33] |

| Uncertainty | Intolerance to uncertainty (β = 0.277, p < 0.001) | Han 2022 [31] |

| Perception and Experience | ||

| Concern about body changes | Concerns about physical changes (β = 0.20, p < 0.01) | Nguyen 2021 [38] |

| Spirituality | ||

| Spirituality | Spiritual well-being (β = −0.304, p < 0.001) | Bilgic 2021 [28] |

| Support and Relationship | ||

| Social support | Perceived social support (β = −0.091, p = 0.019) | Zhou 2021 [45] |

| Social support (β = −0.353, p = 0.001) | Hou 2022 [32] | |

| Spousal support | Lack of spousal support (β = 0.93, p < 0.001) | Huang 2021 [33] |

| Relationship with partner (β = −0.059, p = 0.032) | Zhou 2021 [45] | |

| Satisfaction on husband’s support; dissatisfaction (AOR 11.96, p = 0.001) | Marcelina 2019 [35] | |

| Full spousal support (β = −0.305, p < 0.001 | Han 2022 [31] | |

| Family Function | Good family function (β = −0.32, p < 0.049) | Zhang 2023 [44] |

| Partner violence | Physical intimate partner violence (AOR = 2.47, p < 0.05) | M Hossieni 2017 [36] |

| Factors | Correlations with FOC | Studies |

|---|---|---|

| Psychiatric Disorder | ||

| Psychiatric disorder | Lifetime prevalence of mental illness (r = 0.16, p = 0.01) | Takegata 2014 [40] |

| Psychological Determinants | ||

| Psychological well-being | Psychological well-being (r = −0.49, p < 0.001) | Anjum 2023 [26] |

| Happiness | Happiness (r = −0.69, p < 0.05) | Abdollahpour 2018 [24] |

| Perception and Experience | ||

| Previous birth experience | Past pregnancy experience (r = −0.17, p < 0.05) | Korukcu 2019 [34] |

| Spirituality | ||

| Spirituality | Spiritual intelligence (r = −0.73, p < 0.05) | Abdollahpour 2018 [24] |

| Spiritual intelligence (r = −0.163, p = 0.025) | Mohamadirizi 2017 [37] | |

| COVID-19 | ||

| COVID-19 infection | COVID-19 Anxiety (r = 0.138, p = 0.013) | Aksoy 2023 [25] |

| COVID-19 Obsession (r = 0.216, p < 0.001) | Aksoy 2023 [25] | |

| COVID-19 Fear (r = 0.268, p < 0.001) | Tiryaki 2022 [41] | |

| COVID-19 Fear (r = 0.130; p = 0.011) | Ulu 2022 [42] | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kalok, A.; Kamisan Atan, I.; Sharip, S.; Safian, N.; Shah, S.A. Psychosocial Determinants of Childbirth Fear Among Asian Women: A Scoping Review. Healthcare 2025, 13, 1535. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13131535

Kalok A, Kamisan Atan I, Sharip S, Safian N, Shah SA. Psychosocial Determinants of Childbirth Fear Among Asian Women: A Scoping Review. Healthcare. 2025; 13(13):1535. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13131535

Chicago/Turabian StyleKalok, Aida, Ixora Kamisan Atan, Shalisah Sharip, Nazarudin Safian, and Shamsul Azhar Shah. 2025. "Psychosocial Determinants of Childbirth Fear Among Asian Women: A Scoping Review" Healthcare 13, no. 13: 1535. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13131535

APA StyleKalok, A., Kamisan Atan, I., Sharip, S., Safian, N., & Shah, S. A. (2025). Psychosocial Determinants of Childbirth Fear Among Asian Women: A Scoping Review. Healthcare, 13(13), 1535. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13131535