Effect of Instant Messaging-Based Integrated Healthcare on Medical Service Use and Care Outcomes in Patients with Disabilities

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

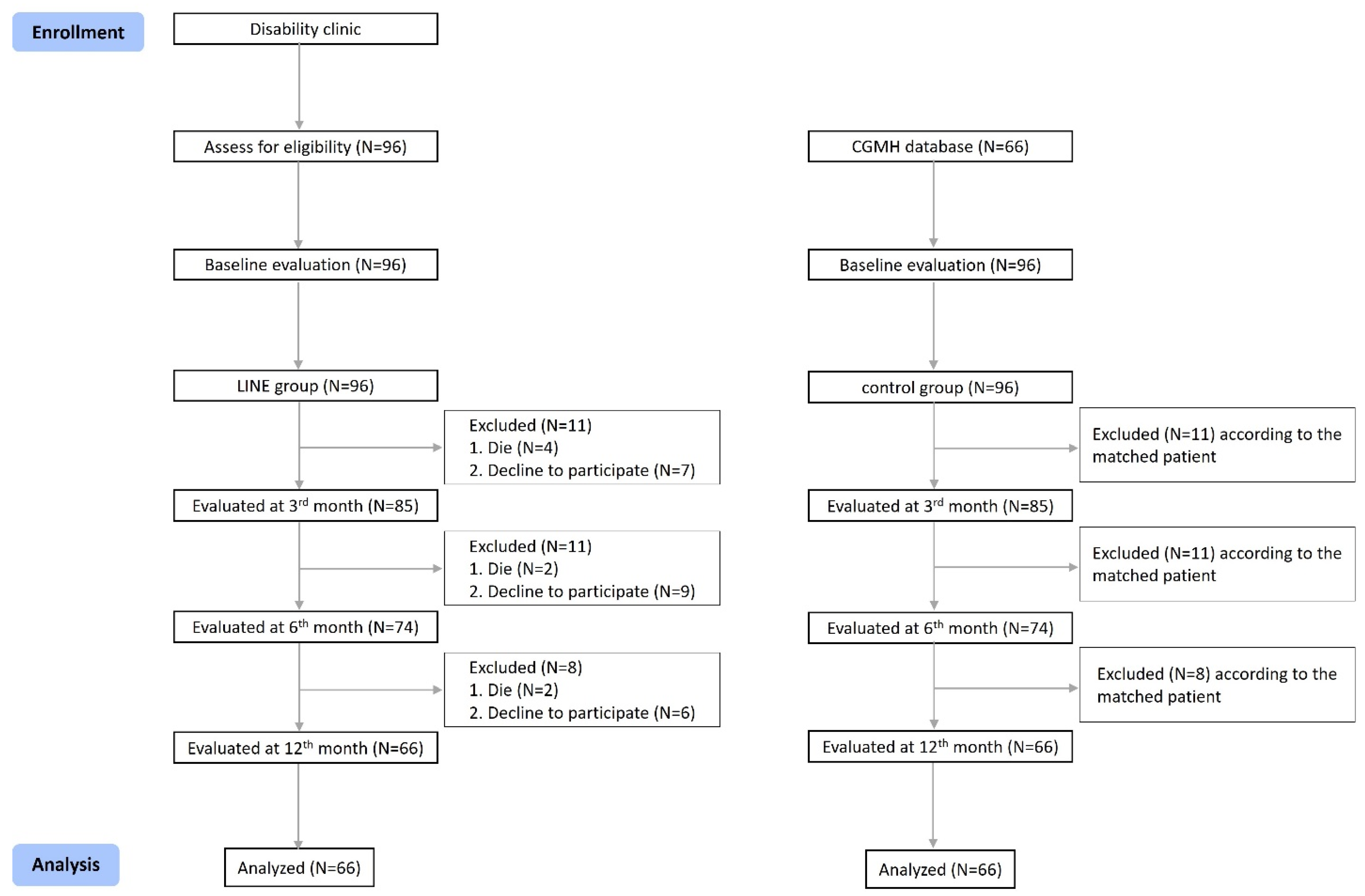

2.1. Study Design and Participants

2.2. Sources and Measurement of Data

2.3. The World Health Organization Quality of Life Brief Version (WHOQOL-BREF)

2.4. Caregiver Burden Inventory (CBI)

2.5. Social Support Rating Scale (SSRS)

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

Study Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CBI | Care burden index |

| WHOQOL-BREF | The World Health Organization Quality of Life Brief Version |

| SSRS | Social support rating scale |

| ADL | Activities of daily living |

| QOL | Quality of life |

References

- O’Young, B.; Gosney, J.; Ahn, C. The Concept and Epidemiology of Disability. Phys. Med. Rehabil. Clin. N. Am. 2019, 30, 697–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministry of Health and Welfare, T.R.O.C. The Disabled Population. 2021–2024. Available online: https://dep.mohw.gov.tw/dos/cp-5224-62359-113.html (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- Rau, C.-L.; Chen, Y.-P.; Lin, C.-Y.; Liou, T.-H. Preliminary Study of Disability Special Medical Clinic Initiative in Taiwan. J. Long-Term Care 2012, 10, 252–264. [Google Scholar]

- Iezzoni, L.I.; Davis, R.B.; Soukup, J.; O’Day, B. Satisfaction with quality and access to health care among people with disabling conditions. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2002, 14, 369–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McConkey, R.; Taggart, L.; Kane, M. Optimizing the uptake of health checks for people with intellectual disabilities. J. Intellect. Disabil. 2015, 19, 205–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McColl, M.A.; Aiken, A.; Schaub, M. Do people with disabilities have difficulty finding a family physician? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2015, 12, 4638–4651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McColl, M.A.; Jarzynowska, A.; Shortt, S.E.D. Unmet health care needs of people with disabilities: Population level evidence. Disabil. Soc. 2010, 25, 205–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soltani, S. Unmet health-care needs in people with disabilities: An evidence to make reforms in health insurance programs in Iran. J. Res. Med. Sci. 2018, 23, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pimlott, N. Who has time for family medicine? Can. Fam. Physician 2008, 54, 14–16. [Google Scholar]

- Pharr, J.R. Accommodations for patients with disabilities in primary care: A mixed methods study of practice administrators. Glob. J. Health Sci. 2013, 6, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, S.-H.; Hsu, S.-Y. Big data analytics for investigating Taiwan Line sticker social media marketing. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2020, 32, 589–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, T.N.; Cheng, P.L.; Chang, P.L. Evaluate the Usability of the Mobile Instant Messaging Software in the Elderly. Stud. Health Technol. Inform. 2017, 245, 818–822. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chiang, K.F.; Wang, H.H. Nurses’ experiences of using a smart mobile device application to assist home care for patients with chronic disease: A qualitative study. J. Clin. Nurs. 2016, 25, 2008–2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Tolly, K.M.; Constant, D. Integrating mobile phones into medical abortion provision: Intervention development, use, and lessons learned from a randomized controlled trial. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2014, 2, e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilmore, L.A.; Klempel, M.C.; Martin, C.K.; Myers, C.A.; Burton, J.H.; Sutton, E.F.; Redman, L.M. Personalized Mobile Health Intervention for Health and Weight Loss in Postpartum Women Receiving Women, Infants, and Children Benefit: A Randomized Controlled Pilot Study. J. Womens Health 2017, 26, 719–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, G.; Chung, C.W.; Yu, C.F.; Wang, J.D. Development and verification of validity and reliability of the WHOQOL-BREF Taiwan version. J. Formos. Med. Assoc. 2002, 101, 342–351. [Google Scholar]

- Vahedi, S. World Health Organization Quality-of-Life Scale (WHOQOL-BREF): Analyses of Their Item Response Theory Properties Based on the Graded Responses Model. Iran. J. Psychiatry 2010, 5, 140–153. [Google Scholar]

- Aung, T.N.N.; Aung, M.N.; Moolphate, S.; Koyanagi, Y.; Supakankunti, S.; Yuasa, M. Caregiver Burden and Associated Factors for the Respite Care Needs among the Family Caregivers of Community Dwelling Senior Citizens in Chiang Mai, Northern Thailand. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, S.Y. The theoretical basis and research applications of the social support scale. J. Clin. Psychiatry 1994, 4, 98–100. [Google Scholar]

- Cauce, A.M.; Felner, R.D.; Primavera, J. Social support in high-risk adolescents: Structural components and adaptive impact. Am. J. Community Psychol. 1982, 10, 417–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Li, S.; Fan, L. Risk Factors of Psychological Disorders After the COVID-19 Outbreak: The Mediating Role of Social Support and Emotional Intelligence. J. Adolesc. Health 2021, 69, 696–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, X.; Liu, C.; Li, N. Social support and Quality of Life: A cross-sectional study on survivors eight months after the 2008 Wenchuan earthquake. BMC Public Health 2010, 10, 573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, C.; Wang, G.; Shi, X.; Cao, F. Social support and depressive symptoms among physicians in tertiary hospitals in China: A cross-sectional study. BMC Psychiatry 2021, 21, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masnoon, N.; Shakib, S.; Kalisch-Ellett, L.; Caughey, G.E. What is polypharmacy? A systematic review of definitions. BMC Geriatr. 2017, 17, 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kojima, T.; Hamaya, H.; Ishii, S.; Hattori, Y.; Akishita, M. Association of disability level with polypharmacy and potentially inappropriate medication in community dwelling older people. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2023, 106, 104873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, T.; Itoh, T.; Yabe, A.; Imai, S.; Nakamura, Y.; Mizokami, Y.; Okouchi, Y.; Ikeshita, A.; Kominato, H. Polypharmacy is associated with malnutrition and activities of daily living disability among daycare facility users: A cross-sectional study. Medicine 2021, 100, e27073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.A.; Brettler, J.W.; Kanter, M.H.; Steinberg, S.G.; Khang, P.; Distasio, C.C.; Martin, J.; Dreskin, M.; Thompson, N.H.; Cotter, T.M.; et al. Refining the Definition of Polypharmacy and Its Link to Disability in Older Adults: Conceptualizing Necessary Polypharmacy, Unnecessary Polypharmacy, and Polypharmacy of Unclear Benefit. Perm J. 2020, 24, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pazan, F.; Wehling, M. Polypharmacy in older adults: A narrative review of definitions, epidemiology and consequences. Eur. Geriatr. Med. 2021, 12, 443–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.U.; Sherifali, D.; Fitzpatrick-Lewis, D.; Kenny, M.; Liu, A.; Lamarche, L.; Mangin, D.; Raina, P. Polypharmacy and mobility outcomes. Mech. Ageing Dev. 2020, 192, 111356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshimura, Y.; Matsumoto, A.; Momosaki, R. Pharmacotherapy and the Role of Pharmacists in Rehabilitation Medicine. Prog. Rehabil. Med. 2022, 7, 20220025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumoto, A.; Yoshimura, Y.; Nagano, F.; Bise, T.; Kido, Y.; Shimazu, S.; Shiraishi, A. Polypharmacy and Its Association with Dysphagia and Malnutrition among Stroke Patients with Sarcopenia. Nutrients 2022, 14, 4251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumoto, A.; Yoshimura, Y.; Nagano, F.; Bise, T.; Kido, Y.; Shimazu, S.; Shiraishi, A. Polypharmacy and potentially inappropriate medications in stroke rehabilitation: Prevalence and association with outcomes. Int. J. Clin. Pharm. 2022, 44, 749–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McMahon, M.; Hatton, C.; Bowring, D.L. Polypharmacy and psychotropic polypharmacy in adults with intellectual disability: A cross-sectional total population study. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2020, 64, 834–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liping, Z. Relationship between health education plan and hospitalization frequency in the children with respiratory tract infection. Pak. J. Pharm. Sci. 2015, 28 (Suppl. S1), 393–395. [Google Scholar]

- Van Elderen, T.; Maes, S.; Seegers, G.; Kragten, H.; Wely, L.R.-V. Effects of a post-hospitalization group health education programme for patients with coronary heart disease. Psychol. Health 1994, 9, 317–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leung, D.Y.P.; Chan, H.Y.L.; Chiu, P.K.C.; Lo, R.S.K.; Lee, L.L.Y. Source of Social Support and Caregiving Self-Efficacy on Caregiver Burden and Patient’s Quality of Life: A Path Analysis on Patients with Palliative Care Needs and Their Caregivers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devkota, H.R.; Murray, E.; Kett, M.; Groce, N. Healthcare provider’s attitude towards disability and experience of women with disabilities in the use of maternal healthcare service in rural Nepal. Reprod. Health 2017, 14, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trani, J.F.; Barbou-des-Courieres, C. Measuring equity in disability and healthcare utilization in Afghanistan. Med. Confl. Surviv. 2012, 28, 219–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulcahy, A.; Streed, C.G., Jr.; Wallisch, A.M.; Batza, K.; Kurth, N.; Hall, J.P.; McMaughan, D.J. Gender Identity, Disability, and Unmet Healthcare Needs among Disabled People Living in the Community in the United States. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 2588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maart, S.; Jelsma, J. Disability and access to health care—A community based descriptive study. Disabil. Rehabil. 2014, 36, 1489–1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Park, J.H. Disability and Emergency Department Visits: A Path Analysis of the Mediating Effects of Unmet Healthcare Needs and Chronic Diseases. Inquiry 2023, 60, 469580231182863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutwali, R.; Ross, E. Disparities in physical access and healthcare utilization among adults with and without disabilities in South Africa. Disabil. Health J. 2019, 12, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| LINE Group (n = 66) | Control Group (n = 66) | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (mean ± SD) | 64.1 ± 14.7 | 68.7 ± 13.8 | 0.066 | |

| Sex (n) | male | 30 | 30 | 1.0 |

| female | 36 | 36 | ||

| Education (n) | low literacy | 14 | 11 | 0.672 |

| less than junior high school | 17 | 21 | ||

| high school or above | 35 | 34 |

| LINE Group | p | Control Group | p | p Between Groups | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 3 Months | 6 Months | 12 Months | Within Group | Baseline | 3 Months | 6 Months | 12 Months | Within Group | p1 | p2 | p3 | |

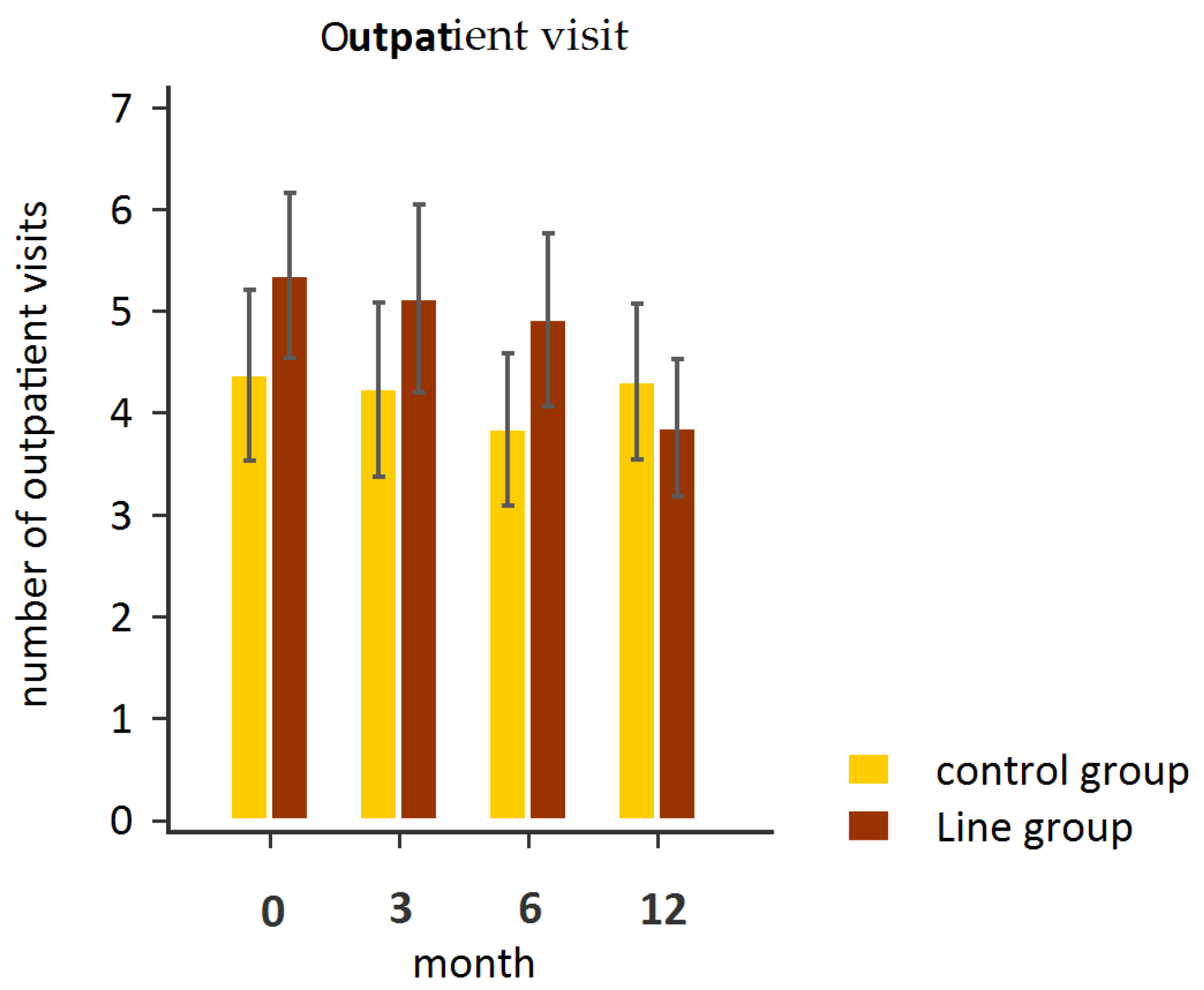

| outpatient visit (mean ± SD; median) | 5.4 ± 3.3 5 | 5.1 ± 3.7 4 | 4.9 ± 3.5 4 | 3.9 ± 2.7 3 | 0.001 * | 4.4 ± 3.4 3 | 4.2 ± 3.5 3 | 3.8 ± 3.0 3 | 4.3 ± 3.1 3 | 0.125 | 0.415 | 0.022 * | <0.001 * |

| hospitalization (mean ± SD; median) | 0.1 ± 0.3 0 | 0.1 ± 0.4 0 | 0.1 ± 0.3 0 | 0.2 ± 0.6 0 | 0.505 | 0.1 ± 0.3 0 | 0.0 ± 0.1 0 | 0.0 ± 0.2 0 | 0.0 ± 0.1 0 | 0.865 | 0.346 | 0.396 | 0.764 |

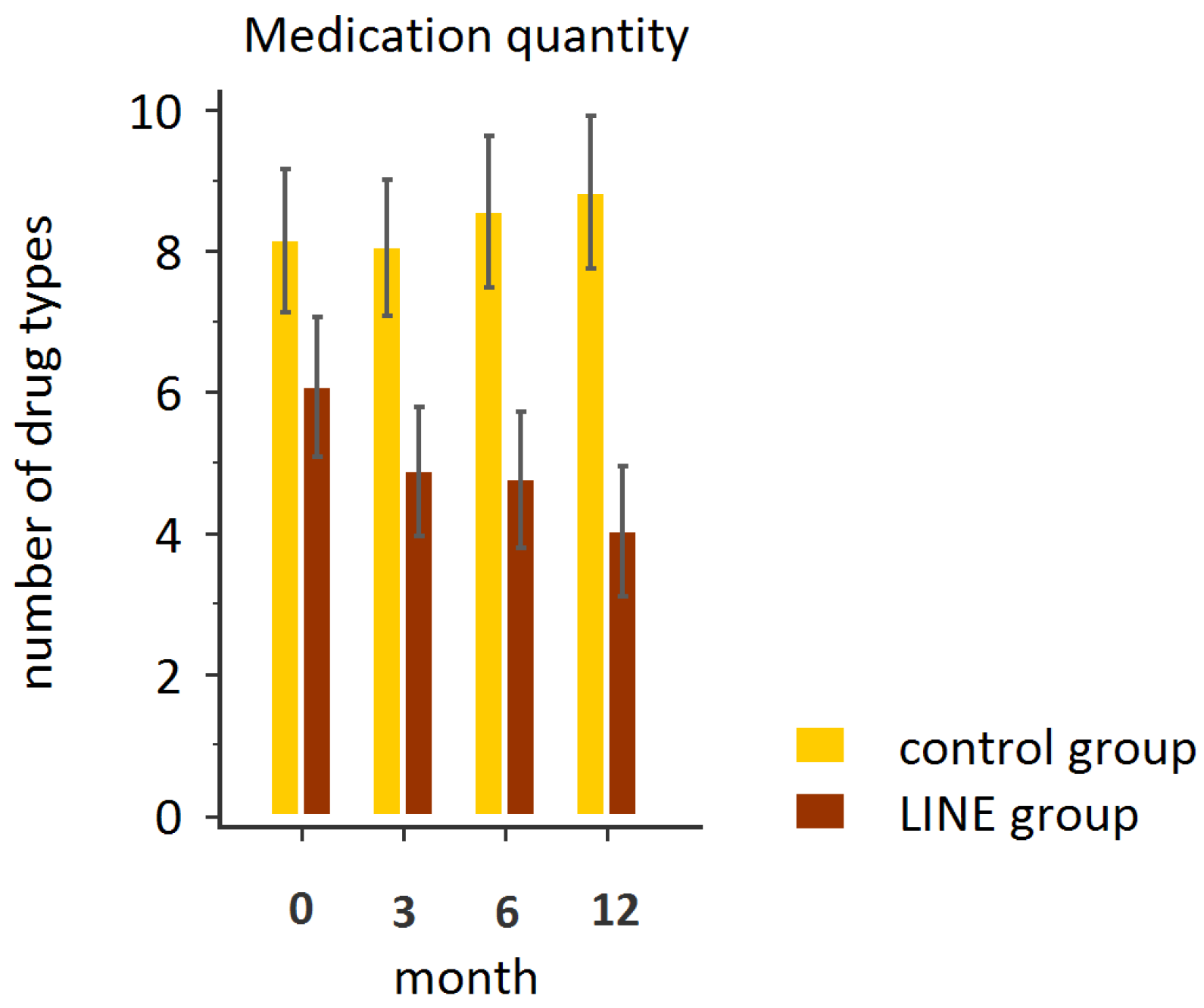

| medication quantity (mean ± SD; median) | 6.9 ± 4.0 6 | 4.9 ± 3.7 4 | 4.8 ± 3.9 5 | 4.0 ± 3.7 3.5 | <0.001 * | 8.1 ± 4.1 8 | 8.1 ± 3.9 7.5 | 8.6 ± 4.3 8 | 8.8 ± 4.4 8.5 | 0.063 | 0.028 * | 0.165 | 0.026 * |

| Outcome | Group Effect (η2) | Time Effect (η2) | Interaction Effect (η2) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Outpatient visits | 0.012 | 0.036 | 0.040 |

| Hospitalization | 0.073 | 0.0019 | 0.006 |

| Medication quantity | 0.200 | 0.018 | 0.057 |

| Baseline | 3 Months | 6 Months | 12 Months | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SSRS (mean ± SD) | 57.5 ± 10.0 | 57.8 ± 9.9 | 57.5 ± 10.7 | 56.1 ± 10.5 | 0.205 |

| WHOQOL-BREF (mean ± SD) | 49.8 ± 6.3 | 48.8 ± 6.3 | 50.8 ± 9.1 | 49.2 ± 7.0 | 0.588 |

| CBI (mean ± SD) | 45.7 ± 15.6 | 43.9 ± 14.6 | 42.5 ± 16.0 | 41.8 ± 16.4 | 0.024 * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hsieh, H.-C.; Lee, Y.-Y.; Chen, N.-C.; Hu, Y.-C.; Wang, L.-Y. Effect of Instant Messaging-Based Integrated Healthcare on Medical Service Use and Care Outcomes in Patients with Disabilities. Healthcare 2025, 13, 1335. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13111335

Hsieh H-C, Lee Y-Y, Chen N-C, Hu Y-C, Wang L-Y. Effect of Instant Messaging-Based Integrated Healthcare on Medical Service Use and Care Outcomes in Patients with Disabilities. Healthcare. 2025; 13(11):1335. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13111335

Chicago/Turabian StyleHsieh, Han-Chin, Yan-Yuh Lee, Nai-Ching Chen, Ya-Chuan Hu, and Lin-Yi Wang. 2025. "Effect of Instant Messaging-Based Integrated Healthcare on Medical Service Use and Care Outcomes in Patients with Disabilities" Healthcare 13, no. 11: 1335. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13111335

APA StyleHsieh, H.-C., Lee, Y.-Y., Chen, N.-C., Hu, Y.-C., & Wang, L.-Y. (2025). Effect of Instant Messaging-Based Integrated Healthcare on Medical Service Use and Care Outcomes in Patients with Disabilities. Healthcare, 13(11), 1335. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13111335