The Mediation Role of Emotion Regulation in the Relationship Between Anxiety and Depression in University Students with Specific Learning Disorder

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Self-Report Measures

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Differences in Emotion Regulation, Anxiety, and Depression Between SLD and TD Groups

3.2. Differences in DERS Subtest Between SLD and TD Groups

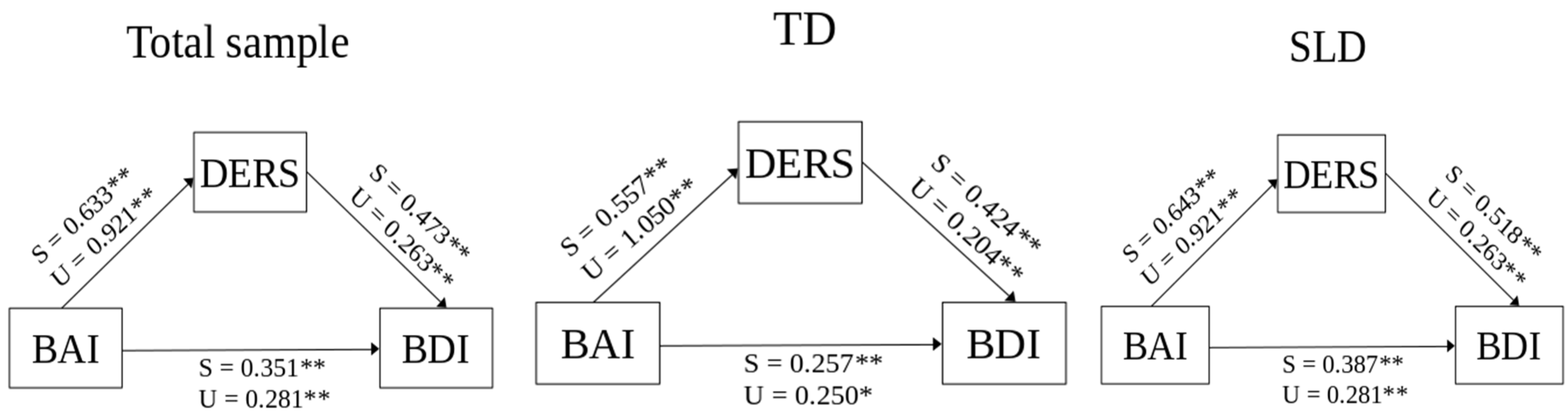

3.3. Model

4. Discussion

4.1. Clinical Implications

4.2. Limitations

4.3. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5), 5th ed.; American Psychiatric Publishing: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Cristofani, P.; Di Lieto, M.C.; Casalini, C.; Pecini, C.; Baroncini, M.; Pessina, O.; Gasperini, F.; Dasso Lang, M.B.; Bartoli, M.; Chilosi, A.M.; et al. Specific Learning Disabilities and Emotional-Behavioral Difficulties: Phenotypes and Role of the Cognitive Profile. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 1882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gross, J.J. Emotion Regulation: Affective, Cognitive, and Social Consequences. Psychophysiology 2002, 39, 281–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gratz, K.L.; Roemer, L. Multidimensional Assessment of Emotion Regulation and Dysregulation: Development, Factor Structure, and Initial Validation of the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale. J. Psychopathol. Behav. 2004, 26, 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thayer, J.F. Gender Differences in the Relationship between Emotional Regulation and Depressive Symptoms. Cogn. Ther. Res. 2003, 27, 349–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolen-Hoeksema, S. Emotion Regulation and Psychopathology: The Role of Gender. Ann. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2012, 8, 161–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmassi, C.; Conti, L.; Gravina, D.; Nardi, B.; Dell’Osso, L. Emotional Dysregulation as Trans-Nosographic Psychopathological Dimension in Adulthood: A Systematic Review. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 900277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becerra, R.; Cruise, K.; Murray, G.; Bassett, D.; Harms, C.; Allan, A.; Hood, S. Emotion Regulation in Bipolar Disorder: Are Emotion Regulation Abilities Less Compromised in Euthymic Bipolar Disorder than Unipolar Depressive or Anxiety Disorders? Open J. Psychiatr. 2013, 3, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodgson, A.R.; Freeston, M.H.; Honey, E.; Rodgers, J. Facing the Unknown: Intolerance of Uncertainty in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder. J. Appl. Res. Intellect. 2016, 30, 336–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheppes, G.; Suri, G.; Gross, J.J. Emotion Regulation and Psychopathology. Ann. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2015, 11, 379–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surman, C.B.; Biederman, J.; Spencer, T.; Miller, C.A.; Petty, C.R.; Faraone, S.V. Neuropsychological deficits are not predictive of deficient emotional self-regulation in adults with ADHD. J. Atten. Disord. 2015, 19, 1046–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jauregui, P.; Estévez, A.; Urbiola, I. Pathological Gambling and Associated Drug and Alcohol Abuse, Emotion Regulation, and Anxious-Depressive Symptomatology. J. Behav. Addict. 2016, 5, 251–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mansueto, G.; Sassaroli, S.; Ruggiero, G.M.; Caselli, G.; Nocita, R.; Spada, M.M.; Palmieri, S. The mediating role of emotion dysregulation in the association between perfectionism and eating psychopathology symptoms. Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 2024, 31, e3020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cisler, J.M.; Olatunji, B.O. Emotion Regulation and Anxiety Disorders. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2012, 14, 182–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Avanzato, C.; Joormann, J.; Siemer, M.; Gotlib, I.H. Emotion Regulation in Depression and Anxiety: Examining Diagnostic Specificity and Stability of Strategy Use. Cogn. Ther. Res. 2013, 37, 968–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joormann, J.; Stanton, C.H. Examining Emotion Regulation in Depression: A Review and Future Directions. Behav. Res. Ther. 2016, 86, 35–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamber, M.D.; Kraenzle Schneider, J. Mindfulness-Based Meditation to Decrease Stress and Anxiety in College Students: A Narrative Synthesis of the Research. Educ. Res. Rev. 2016, 18, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beddoe, A.E.; Murphy, S.O. Does Mindfulness Decrease Stress and Foster Empathy among Nursing Students? J. Nurs. Educ. 2018, 43, 305–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, S.; Perveen, A. Mindfulness and Anxiety among University Students: Moderating Role of Cognitive Emotion Regulation. Curr. Psychol. 2021, 42, 5621–5628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, J.J. Emotion Regulation: Taking Stock and Moving Forward. Emotion 2013, 13, 359–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schäfer, J.Ö.; Naumann, E.; Holmes, E.A.; Tuschen-Caffier, B.; Samson, A.C. Emotion Regulation Strategies in Depressive and Anxiety Symptoms in Youth: A Meta-Analytic Review. J. Youth Adolesc. 2016, 46, 261–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dochnal, R. Emotion Regulation among Adolescents with Pediatric Depression as a Function of Anxiety Comorbidity. Front Psychiatry 2010, 25, 722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muris, P.; Merckelbach, H.; Schmidt, H.; Gadet, B.; Bogie, N. Anxiety and Depression as Correlates of Self-Reported Behavioural Inhibition in Normal Adolescents. Behav. Res. Ther. 2001, 39, 1051–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garnefski, N.; Legerstee, J.; Kraaij, V.; van Den Kommer, T.; Teerds, J.A.N. Cognitive coping strategies and symptoms of depression and anxiety: A comparison between adolescents and adults. J. Adolesc. 2002, 25, 603–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barlow, D.H.; Allen, L.B.; Choate, M.L. Toward a Unified Treatment for Emotional Disorders. Behav. Ther. 2004, 35, 205–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGlinchey, E.; Kirby, K.; McElroy, E.; Murphy, J. The Role of Emotional Regulation in Anxiety and Depression Symptom Interplay and Expression among Adolescent Females. J. Psychopathol. Behav. 2021, 43, 854–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, Q.-N.; Chen, Y.-H.; Yan, W.-J. A Network Analysis of Difficulties in Emotion Regulation, Anxiety, and Depression for Adolescents in Clinical Settings. Child. Adol. Psych. Ment. Health 2023, 17, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonifacci, P.; Tobia, V.; Marra, V.; Desideri, L.; Baiocco, R.; Ottaviani, C. Rumination and Emotional Profile in Children with Specific Learning Disorders and Their Parents. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özyurt, G.; Öztürk, Y.; Turan, S.; Çıray, R.O.; Tanıgör, E.K.; Ermiş, Ç.; Tufan, A.E.; Akay, A. Are Communication Skills, Emotion Regulation and Theory of Mind Skills Impaired in Adolescents with Developmental Dyslexia? Dev. Neuropsychol. 2024, 49, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouvava, S.; Antonopoulou, K.; Kokkinos, C.M.; Ralli, A.M.; Maridaki-Kassotaki, K. Friendship Quality, Emotion Understanding, and Emotion Regulation of Children with and without Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder or Specific Learning Disorder. Emot. Behav. Difficulties 2021, 27, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scorza, M.; Gontkovsky, S.T.; Puddu, M.; Ciaramidaro, A.; Termine, C.; Simeoni, L.; Mauro, M.; Benassi, E. Cognitive Profile Discrepancies among Typical University Students and Those with Dyslexia and Mixed-Type Learning Disorder. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 7113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith-Spark, J.H.; Henry, L.A.; Messer, D.J.; Edvardsdottir, E.; Zięcik, A.P. Executive Functions in Adults with Developmental Dyslexia. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2016, 53-54, 323–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Camia, M.; Benassi, E.; Giovagnoli, S.; Scorza, M. Specific Learning Disorders in Young Adults: Investigating Pragmatic Abilities and Their Relationship with Theory of Mind, Executive Functions and Quality of Life. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2022, 126, 104253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carroll, J.M.; Iles, J.E. An Assessment of Anxiety Levels in Dyslexic Students in Higher Education. Brit. J. Educ. Psychol. 2006, 76, 651–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, T.E.; Nida, R.E.; Zlomke, K.R.; Nebel-Schwalm, M.S. Health-Related Quality of Life in College Undergraduates with Learning Disabilities: The Mediational Roles of Anxiety and Sadness. J. Psychopathol. Behav. Assess. 2008, 31, 228–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghisi, M.; Bottesi, G.; Re, A.M.; Cerea, S.; Mammarella, I.C. Socioemotional Features and Resilience in Italian University Students with and without Dyslexia. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, J.M.; Gregg, N. Depression and Anxiety among Transitioning Adolescents and College Students with ADHD, Dyslexia, or Comorbid ADHD/Dyslexia. J. Atten. Disord. 2010, 16, 244–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Xie, Y.; Sun, Z.; Liu, D.; Yin, H.; Shi, L. Factors associated with academic burnout and its prevalence among university students: A cross-sectional study. BMC Med. Educ. 2023, 23, 317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alawadhi, Y.T.; Smith, M.R.; King, K.M. The relations between real-time use of emotion regulation strategies and anxiety and depression symptoms. J. Clin. Psychol. 2023, 79, 1082–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaughlin, K.A.; Nolen-Hoeksema, S. Rumination as a transdiagnostic factor in depression and anxiety. Behav. Res. Ther. 2011, 49, 186–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velotti, P.; Garofalo, C.; Petrocchi, C.; Cavallo, F.; Popolo, R.; Dimaggio, G. Alexithymia, emotion dysregulation, impulsivity and aggression: A multiple mediation model. Psychiatry Res. 2016, 237, 296–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. World Report on Ageing and Health; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Istituto Superiore di Sanità. Consensus conference: Disturbi Specifici Dell’apprendimento. Sistema Nazionale Perle Linee Guida. Ministero Della Salute. 2011. Available online: https://www.aiditalia.org/storage/files/dislessia-che-fare/Cc_Disturbi_Apprendimento.pdf (accessed on 20 March 2025).

- Sighinolfi, C.; Pala, A.N.; Chiri, L.R.; Marchetti, I.; Sica, C. Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale (DERS): Traduzione E Adattamento Italiano. Psicoter. Cogn. Comport. 2010, 16, 141–170. [Google Scholar]

- Beck, A.T.; Epstein, N.; Brown, G.; Steer, R. Beck Anxiety Inventory. J. Consult. Clin. Psych. 1993, 56, 893–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sica, C.; Ghisi, M. The Italian versions of the Beck Anxiety Inventory and the Beck Depression Inventory-II: Psychometric properties and discriminant power. In Leading-Edge Psychological Tests and Testing Research; Lange, M.A., Ed.; Nova Science Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 2007; pp. 27–50. [Google Scholar]

- Beck, A.T.; Ward, C.H.; Mendelson, M.; Mock, J.; Erbaugh, J. An Inventory for Measuring Depression. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 1961, 4, 561–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghisi, M.; Flebus, G.B.; Montano, A.; Sanavio, E.; Sica, C. Beck Depression Inventory, 2nd ed.; Pearson: Florence, Italy, 2006; pp. 67–82. [Google Scholar]

- IBM Corp. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 26.0; IBM Corp.: Armonk, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- JASP Team. JASP, Version 0.19.3. 2024. Available online: https://jasp-stats.org/ (accessed on 20 March 2025).

- The Jamovi Project. Jamovi. (Version 2.5). 2024. Available online: https://www.jamovi.org (accessed on 20 March 2025).

- Gallucci, M. PATHj: Jamovi Path Analysis [Jamovi Module]. 2021. Available online: https://pathj.github.io/ (accessed on 20 March 2025).

- Anderson, L.M.; Reilly, E.E.; Gorrell, S.; Schaumberg, K.; Anderson, D.A. Gender-Based Differential Item Function for the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2016, 92, 87–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ando’, A.; Giromini, L.; Ales, F.; Zennaro, A. A Multimethod Assessment to Study the Relationship between Rumination and Gender Differences. Scand. J. Psychol. 2020, 61, 740–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malesza, M. Relationship between Emotion Regulation, Negative Affect, Gender and Delay Discounting. Curr. Psychol. 2019, 40, 4031–4039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hampel, P.; Petermann, F. Perceived Stress, Coping, and Adjustment in Adolescents. J. Adolesc. Health 2006, 38, 409–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gennaro, A.; Scorza, M.; Benassi, E.; Zonno, M.; Stella, G.; Salvatore, S. The role of perceived learning environment in scholars: A comparison between university students with dyslexia and normal readers. Int. J. Disabil. Hum. Dev. 2019, 18, 107–115. [Google Scholar]

- Scorza, M.; Zonno, M.; Benassi, E. Dyslexia and Psychopathological Symptoms in Italian University Students: A Higher Risk for Anxiety Disorders in Male Population? J. Psychopathol. 2018, 24, 193–203. [Google Scholar]

- Livingston, E.M.; Siegel, L.S.; Ribary, U. Developmental Dyslexia: Emotional Impact and Consequences. Aust. J. Learn. Difficulties 2018, 23, 107–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, L.D.; Nolen-Hoeksema, S. Gender Differences in Responses to Depressed Mood in a College Sample. Sex Roles 1994, 30, 331–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basta, M.; Micheli, K.; Koutra, K.; Fountoulaki, M.; Dafermos, V.; Drakaki, M.; Faloutsos, K.; Soumaki, E.; Anagnostopoulos, D.; Papadakis, N.; et al. Depression and Anxiety Symptoms in Adolescents and Young Adults in Greece: Prevalence and Associated Factors. J. Affect. Disord. 2022, 8, 100334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alt, M.; Fox, A.; Levy, R.; Hogan, T.P.; Cowan, N.; Gray, S. Phonological Working Memory and Central Executive Function Differ in Children with Typical Development and Dyslexia. Dyslexia 2021, 28, 20–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crisci, G.; Caviola, S.; Cardillo, R.; Mammarella, I.C. Executive functions in neurodevelopmental disorders: Comorbidity overlaps between attention deficit and hyperactivity disorder and specific learning disorders. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2021, 15, 594234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Carvalho, C.A.F.; Kida, A.d.S.; Capellini, S.A.; de Avila, C.R.B. Phonological Working Memory and Reading in Students with Dyslexia. Front. Psychol. 2014, 5, 746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ferrara, M.; Benassi, E.; Camia, M.; Scorza, M. Application to Adolescents of a Pure Set-Shifting Measure for Adults: Identification of Poor Shifting Skills in the Group with Developmental Dyslexia. Mediterr. J. Clin. Psychol. 2022, 10, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groves, N.B.; Wells, E.L.; Soto, E.F.; Marsh, C.L.; Jaisle, E.M.; Harvey, T.K.; Kofler, M.J. Executive Functioning and Emotion Regulation in Children with and without ADHD. Res. Child. Adolesc. Psychopathol. 2021, 50, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zelazo, P.D.; Cunningham, W.A. Executive Function: Mechanisms Underlying Emotion Regulation. In Handbook of Emotion Regulation; Gross, J.J., Ed.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2007; pp. 135–158. [Google Scholar]

- Battistutta, L.; Schiltz, C.; Steffgen, G. The Mediating Role of ADHD Symptoms and Emotion Regulation in the Association between Executive Functions and Internalizing Symptoms: A Study among Youths with and without ADHD And/or Dyslexia. Adv. Neurodev. Disord. 2021, 5, 396–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, M.; Williams, N.; Kirby, A. Supporting Students with Specific Learning Difficulties in Higher Education: A Preliminary Comparative Study of Executive Function Skills. JIPHE 2015, 6, 36–47. [Google Scholar]

- Benassi, E.; Camia, M.; Giovagnoli, S.; Scorza, M. Impaired School Well-Being in Children with Specific Learning Disorder and Its Relationship to Psychopathological Symptoms. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 2020, 37, 74–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singer, E. The Strategies Adopted by Dutch Children with Dyslexia to Maintain Their Self-Esteem When Teased at School. J. Learn. Disabil. 2005, 38, 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Operto, F.F.; Pastorino, G.M.G.; Stellato, M.; Morcaldi, L.; Vetri, L.; Carotenuto, M.; Viggiano, A.; Coppola, G. Facial Emotion Recognition in Children and Adolescents with Specific Learning Disorder. Brain Sci. 2020, 10, 473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Lang, N.D.J.; Ferdinand, R.F.; Ormel, J.; Verhulst, F.C. Latent Class Analysis of Anxiety and Depressive Symptoms of the Youth Self-Report in a General Population Sample of Young Adolescents. Behav. Res. Ther. 2006, 44, 849–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sendzik, L.; Ö. Schäfer, J.; Samson, A.C.; Naumann, E.; Tuschen-Caffier, B. Emotional Awareness in Depressive and Anxiety Symptoms in Youth: A Meta-Analytic Review. J. Youth Adolesc. 2017, 46, 687–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahib, A.; Chen, J.; Cárdenas, D.; Calear, A.L.; Wilson, C. Emotion regulation mediates the relation between intolerance of uncertainty and emotion difficulties: A longitudinal investigation. J. Affect. Disord. 2024, 364, 194–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, K.; Sandman, C.; Craske, M. Positive and Negative Emotion Regulation in Adolescence: Links to Anxiety and Depression. Brain Sci. 2019, 9, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groves, N.B.; Kofler, M.J.; Wells, E.L.; Day, T.N.; Chan, E.S.M. An Examination of Relations among Working Memory, ADHD Symptoms, and Emotion Regulation. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2020, 48, 525–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farah, R.; Ionta, S.; Horowitz-Kraus, T. Neuro-Behavioral Correlates of Executive Dysfunctions in Dyslexia over Development from Childhood to Adulthood. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 708863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moura, O.; Pereira, M.; Alfaiate, C.; Fernandes, E.; Fernandes, B.; Nogueira, S.; Moreno, J.; Simões, M.R. Neurocog-nitive functioning in children with developmental dyslexia and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: Multiple deficits and diagnostic accuracy. J. Clin. Exp. Neuropsychol. 2017, 39, 296–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandstrom, A.; Uher, R.; Pavlova, B. Prospective Association between Childhood Behavioral Inhibition and Anxiety: A Meta-Analysis. Res. Child Adolesc. Psychopathol. 2019, 48, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| SLD Group (n = 50) | TD Group (n = 79) | |

|---|---|---|

| Male | 21 | 34 |

| Female | 29 | 45 |

| Mean age (SD) | 21 (2.8) | 22 (2.3) |

| Group | Mean (SD) | F(df) | p | Partial η2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DERS Total score | TD SLD | 80.11 (18.158) 93.40 (22.019) | 10.879 (1) | 0.001 | 0.080 |

| BAI | TD SLD | 13.11 (9.629) 20.24 (15.376) | 8.060 (1) | 0.005 | 0.061 |

| BDI | TD SLD | 10.28 (8.747) 15.40 (11.190) | 6.421 (1) | 0.013 | 0.049 |

| Group | Mean (SD) | F(df) | p | Partial η2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Nonacceptance | TD SLD | 10.49 (4.320) 13.36 (5.450) | 8.511 (1) | 0.004 | 0.64 |

| 2. Goals | TD SLD | 14.51 (4.966) 16.26 (4.485) | 2.224 (1) | 0.138 | 0.017 |

| 3. Strategies | TD SLD | 16.84 (5.962) 19.64 (6.933) | 5.171 (1) | 0.025 | 0.040 |

| 4. Impulse | TD SLD | 11.18 (4.904) 12.98 (5.479) | 2.646 (1) | 0.106 | 0.021 |

| 5. Clarity | TD SLD | 12.20 (5.236) 14.64 (5.458) | 4.2025 (1) | 0.042 | 0.033 |

| 6. Awareness | TD SLD | 7.51 (3.974) 8.16 (3.530) | 0.701 (1) | 0.404 | 0.006 |

| Relationship | Group | Effect (LLCI-ULCI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BAI → DERS → BDI | Total | Direct | Indirect | |

| Total sample = 129 | 0.650 ** (0.518–0.757) | 0.351 ** (0.197–0.506) | 0.299 ** (0.206–0.416) | |

| SLD = 50 | 0.720 ** (0.537–0.830) | 0.387 ** (0.214–0.577) | 0.333 ** (0.199–0.462) | |

| TD = 79 | 0.512 ** (0.300–0.663) | 0.275 * (0.020–0.492) | 0.236 ** (0.110–0.405) | |

| Parameter Constraint | χ2 | df | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| p1 = p10 | 0.79 | 1 | 0.373 |

| p2 = p11 | 1.35 | 1 | 0.245 |

| p3 = p12 | 0.30 | 1 | 0.583 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Camia, M.; Ciaramidaro, A.; Benassi, E.; Giovagnoli, S.; Angelini, D.; Rubichi, S.; Scorza, M. The Mediation Role of Emotion Regulation in the Relationship Between Anxiety and Depression in University Students with Specific Learning Disorder. Healthcare 2025, 13, 1211. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13101211

Camia M, Ciaramidaro A, Benassi E, Giovagnoli S, Angelini D, Rubichi S, Scorza M. The Mediation Role of Emotion Regulation in the Relationship Between Anxiety and Depression in University Students with Specific Learning Disorder. Healthcare. 2025; 13(10):1211. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13101211

Chicago/Turabian StyleCamia, Michela, Angela Ciaramidaro, Erika Benassi, Sara Giovagnoli, Damiano Angelini, Sandro Rubichi, and Maristella Scorza. 2025. "The Mediation Role of Emotion Regulation in the Relationship Between Anxiety and Depression in University Students with Specific Learning Disorder" Healthcare 13, no. 10: 1211. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13101211

APA StyleCamia, M., Ciaramidaro, A., Benassi, E., Giovagnoli, S., Angelini, D., Rubichi, S., & Scorza, M. (2025). The Mediation Role of Emotion Regulation in the Relationship Between Anxiety and Depression in University Students with Specific Learning Disorder. Healthcare, 13(10), 1211. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13101211