Abstract

The number of family caregivers of dependent older adults is increasing. The adverse effects of the work provided by these caregivers can have a negative impact on their own physical and mental health, so it is necessary to develop strategies that support and improve the quality of life and functional capacity of this group. Background/Objectives: The aim of this systematic review is to analyze physical exercise interventions for family caregivers and the effects on their physical and mental health, quality of life and functioning. Methods: A comprehensive search was conducted in the scientific databases PubMed, Embase, Scopus and CINAHL. Data extraction was carried out from the selected articles, obtaining information about the characteristics of the study subjects, type and characteristics of the intervention and results. Results: A total of 17 studies were selected for the review. All studies were based on physical exercise interventions and reported significant improvements in caregivers’ physical and mental health, as well as an increase in their quality of life and functioning. Most of the study subjects were older adult women relatives. No adverse effects were found to the interventions. Conclusions: Physical exercise seems to be effective in improving the physical and mental health of family caregivers, increasing their quality of life and functional capacity. More future research is needed to make interventions more accessible to family caregivers.

1. Introduction

In recent decades, global society has experienced a steady increase in population ageing, a trend that is expected to intensify in the coming years. By 2030, it is estimated that one in six people worldwide will be aged 60 or older, with the population in this age group rising from 1 billion to 1.4 billion. Furthermore, by 2050, this number is projected to double to 2.1 billion. The population aged 80 and over is also expected to triple between 2020 and 2050, reaching 426 million individuals [1].

This demographic shift implies a corresponding rise in the number of dependent older adults, as increased life expectancy is often accompanied by multimorbidity and functional decline [2]. The growing number of dependents poses significant economic and social challenges, particularly in light of the global shortage of healthcare professionals and limited financial resources. In this context, informal caregiving—typically provided by family members—has become essential for addressing the needs of dependent older adults. Consequently, the number of family caregivers has been steadily increasing [3,4,5].

Caring for a dependent older adult can be highly stressful and may negatively affect caregivers’ physical and mental health. Numerous studies have documented the decline in health among family caregivers [6,7,8,9,10,11]. For instance, Lambert et al., in a study involving 300 family caregivers, found that caring for a dependent individual significantly reduces caregivers’ quality of life [12]. Similarly, Pinquart and Sörensen, through a meta-analysis of 84 studies comparing caregivers and non-caregivers, reached the same conclusion [13]. In response, a wide range of interventions—primarily based on health education programs—have been developed to support caregivers and enhance their quality of life [14,15].

Also, caregivers have a higher risk of cardiovascular disease than non-caregivers, where the main modifiable risk factor is physical inactivity [16]. Physical activity is beneficial for health, as it not only reduces the risk of cardiovascular diseases, but also improves chronic diseases and reduces pain, thus increasing life expectancy [17]. The World Health Organization (WHO) defines physical exercise as: “A subcategory of physical activity that is planned, structured, repetitive and purposeful in the sense that the improvement or maintenance of one or more components of physical fitness is the objective” [18]. There are studies that show the benefits of physical exercise in patients suffering from metabolic diseases or some type of cancer. In this population, physical exercise shows improvements in general well-being, mental health, sleep quality and even functional capacity [17,19,20].

In summary, physical exercise may enhance both the physical and mental health of family caregivers of dependent older adults, thereby improving their quality of life and functional capacity, and ultimately contributing to the continuity and quality of care provided. According to the existing literature, few reviews have specifically examined the benefits of physical exercise for caregiver health [21,22]. This systematic review aims to analyze and evaluate the current evidence on the effects of physical exercise on the physical and mental health, quality of life and functional capacity of family caregivers of dependent older adults. By doing so, it seeks to expand the limited body of literature on this topic and to highlight emerging intervention strategies—such as telerehabilitation and immersive methods—that have gained traction in recent years.

2. Materials and Methods

This systematic literature review was conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines [23] and was prospectively registered on the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews platform, using the following registration number CRD42025645292. No financial support was provided for this study.

An advanced literature search was conducted in February 2025 in the scientific databases PubMed, Embase, Scopus and CINAHL. The terms used were “exercise”, “physical therapy modalities”, “caregivers”, “physical activity”, “physiotherapy” and “caregiver”, according to the EMTREE thesaurus of the Embase database, CINAHL Headings of CINAHL and MeSH for PubMed and Scopus. See Supplemental Material S2. Only articles that referred to family caregivers of dependent older adults were selected. Additionally, the reference lists of studies identified as eligible following the search were hand-searched to ensure that no relevant studies were missed. Grey literature was not included in our review. All items were stored in Mendeley Reference Manager.

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

The inclusion and exclusion criteria of the studies to be included in the review were defined by the PICOS framework [24]

2.1.1. Inclusion Criteria

(P): Adult population dedicated to the unpaid care of a dependent older adult regardless of sex, age or ethnic origin.

(I): Physical exercise interventions. WHO defines physical exercise as: “A subcategory of physical activity that is planned, structured, repetitive and purposeful in the sense that the improvement or maintenance of one or more components of physical fitness is the objective” [18].

(C): No intervention at all or interventions based on health education programs.

(O): Physical health, mental health, quality of life and functional capacity. Studies whose results are measured by validated scales or questionnaires.

(S): Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) published in any language.

2.1.2. Exclusion Criteria

We did not include reviews, studies conducted in family caregivers of children, professional caregivers, and interventions that do not involve physical activity.

2.2. Study Selection

Two reviewers (AB and CB) independently screened titles/abstracts against the prespecified inclusion/exclusion criteria. For those that met the inclusion criteria, the full texts were obtained. Moreover, if any uncertainty existed, the full text was retrieved for further clarification. If needed, the authors of the original work were contacted. Screening of full texts was conducted in the same manner using the predefined inclusion/exclusion criteria.

Articles were included when eligibility was confirmed by both reviewers. Any disagreement between the two reviewers was first discussed in a consensus meeting between both reviewers, and if no agreement could be made, an independent reviewer (CR) was sought to decide about inclusion/exclusion. Reviewers were not blinded to journal titles or study authors.

2.3. Data Extraction

Data extraction was conducted by one reviewer (AB) and then checked by a second reviewer (CB) through a data extraction sheet previously developed by consensus of all authors.

The following data were extracted from each of the selected articles: first author, year of publication and country; details of the study subjects, such as sample size, sex, age, and relationship to the dependent person; details of the intervention such as exercise modality, number and duration of sessions, and details of the control group; results and main conclusions. This information was synthesized and displayed in a table of characteristics. See Table 1. The extended table can be found in Supplemental Material S1.

Table 1.

Summary of the study characteristics and main results.

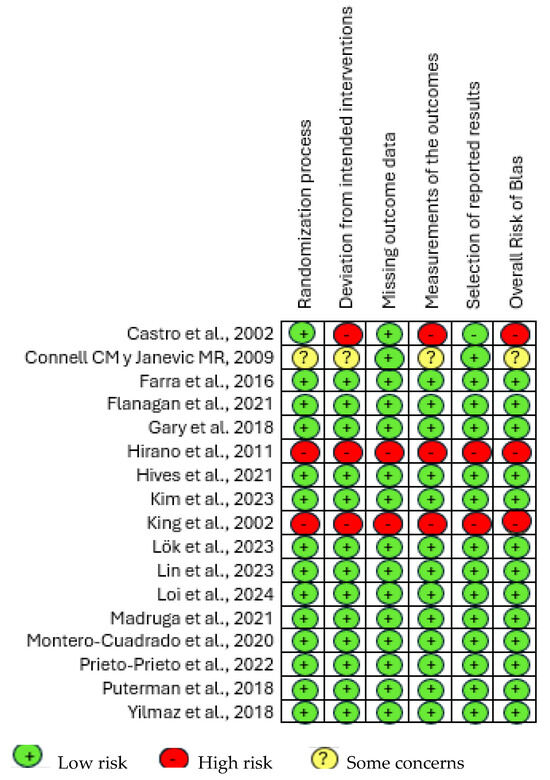

2.4. Quality Assessment and Risk of Bias Assessment

The risk of bias was evaluated using the Cochrane RoB2 tool [42]. This tool is made up of five different domains: randomization process; deviations from planned interventions; lack of result data, measurement tools; and selection of reported findings. In each domain, it is necessary to answer several “signaling questions”. The overall risk of bias may be judged as “high” or “low” or may indicate “some concerns”.

Two independent review authors (EA and JJG) performed the analysis and applied the study scales individually. In the event of a dispute, a third reviewer (AB) would resolve the dispute. Interrater reliability was calculated through Cohen’s Kappa coefficient.

3. Results

3.1. Search Results

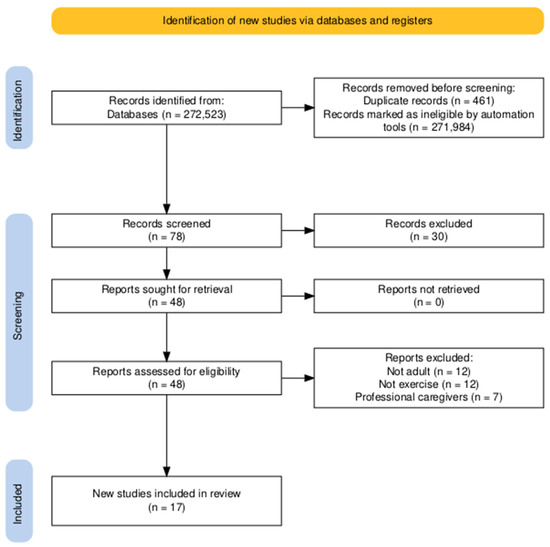

The search in all databases yielded a total of 272,523 articles, of which 271,984 were ineligible and 461 duplicate articles were eliminated. A total of 78 articles were analyzed by title and abstract and 30 articles were excluded because they did not meet any criteria. Finally, 48 articles were analyzed in full text and 31 articles were excluded because they met exclusion criteria. A total of 17 articles were included for the review [25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41]. See Figure 1.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flowchart [23].

3.2. Study Characteristics

All studies included in the review used RCT research designs, providing more accurate evidence. The studies were conducted on a total of 1403 subjects, with the sample size ranging from n = 31 [40] to n = 211 [26]. All studies were conducted in a higher proportion of female caregivers, and in five studies participation was exclusively female [25,27,30,33,41]. The average age range of caregivers in the 17 included articles was 50 to 74 years, studies by Lök et al. and Yilmaz et al. [31,41] indicated the lowest mean age of 50 years and Hirano et al. indicated the highest age of 74 years [40]. All participants in the 17 studies were family carers and most of them were children and spouses.

3.3. Type and Characteristics of Interventions

In the 17 articles included, physical activity interventions aimed at family caregivers were carried out; five of them were based on aerobic exercises [29,34,35,37,38], another study used muscle relaxation exercises [25] and another of article included guided walks [39]. Lök et al. structured the exercises in their study with a warm-up prior to the exercise routine and a cool-down afterwards [41]. There are only two authors who combined a program of physical exercises with a program of education for caregivers to improve their physical health [25,37].

In most studies, exercises were performed individually, authors such as Kim et al. included group sessions [29], and in the study by Lin et al., the exercises were performed at home, but also in a group manner via a social web application [36]. Of the 17 studies included, 10 of them were based on exercises that are performed from home [26,27,28,30,31,32,33,34,36,37]. Most studies offered phone support or motivational text messages. Only four of the studies reported monitoring of participants’ activity via pedometer [26,39,40,41].

The duration of the interventions varied, ranging from 6 weeks [36] to 12 months [26,27,33]. The frequency of most studies was two to three sessions per week, although we found interventions that employed a lower frequency of one session per week [29,41], and a higher frequency of five sessions per week [30,39], studies such as those by Farran et al. or Lin et al. simply set weekly physical activity goals [26,36]. The intensity of the interventions varied widely, although in most cases there was an increase over the course of the study. See Table 1. The extended table can be found in Supplemental Material S1.

3.4. Study Results

3.4.1. Physical Health Results

Of the 17 included studies, there are only seven reported measures of caregivers’ overall physical health, all of which had positive results compared to control groups [25,26,29,34,35,37,40]. Farran et al. further reported improvements in strength and endurance, also measuring the number of steps of participants with the use of a pedometer [26]. Another study further targeted health outcomes by measuring hand grip strength and upper and lower limb strength and found improvements in the 6 min walk test [37]. Some authors conducted a comprehensive study of participants’ physical health, also assessing flexibility and mobility [25,34].

Montero-Cuadrado et al. used the Spanish version of the SF-36 V2, in which patients also reported improvements in pain perception [25]. Puterman et al. went even deeper by measuring, through blood tests, the participants’ telomere length and body mass index, finding positive results and improvements in cardiorespiratory exercises [35].

Other authors also conducted questionnaires and interviews to identify the perception and well-being of the subjects when performing physical exercise [32,34,39], and one of them even analyzed the motivation of caregivers to do any physical activity [33].

3.4.2. Mental Health Results

Most of the studies included reported outcomes on caregivers’ mental health, all of them indicating improvement compared to control groups [25,27,28,29,30,31,32,34,36,37,38,39,40,41]. Only one of the studies concluded that physical activity is beneficial in the mental health of caregivers, except those who cared for people with cognitive impairment; in these cases, the improvement was negligible [30].

The caregiver burden was assessed in eleven of the studies, nine of them using the Zarit scale [25,28,29,30,31,34,38,40,41] and two using validated interviews and questionnaires [26,37].

Depression was measured in nine of the included studies [25,27,28,29,30,31,32,38]. Some of them used the Beck Depression Scale to measure outcomes [27,31], and others used the Geriatric Depression Scale [25,28,29,30,34]. Two of the authors, however, used validated interviews and questionnaires [32,38]. Some of the studies also reported stress level results using the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) [27,29,32,36,39].

3.4.3. Quality of Life and Functional Capacity

Quality of life and functional capacity were assessed by four of the authors, and all of them reported positive results with respect to the control group. Two of the authors used the Spanish version of the SF-36 to measure the results [25,34], and the others used the Healthy Life Style Behavior Scale [29,41].

Two of the studies also assessed sleep quality [27,40], showing significant improvements in subjects in the intervention group.

3.4.4. Adverse Events

None of the studies consulted reported adverse events of interest [25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41].

3.4.5. Dropout Rate

The average dropout rate was 11.8%, with a dropout rate ranging from 0% [39,41] to 25% [30]. Despite the low dropout rate, in most studies attributing attrition to caregiver time constraints, which could have led to some bias, as participants with the highest burden of care were those who dropped out.

3.4.6. Quality of Studies and Risk of Bias Assessment

The majority of studies included in the analysis demonstrated a low risk of bias and a high level of methodological quality [25,26,28,29,30,31,34,35,36,37,38,39,41], and only three of the RCTs appeared to be at high risk of bias [27,33,40]. See Figure 2.

Figure 2.

RoB Chart [25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41].

The interrater reliability was 82.7% (k = 0.827), which refers to a good agreement.

4. Discussion

The aim of this systematic review was to examine the existing evidence on the benefits of physical exercise on the physical and mental health of family caregivers of dependent older adults. A total of 17 studies were reviewed, most of which involved older adult female caregivers. The findings indicate that physical activity significantly improves both the physical and mental health of family caregivers, positively impacting their quality of life and functional capacity in the same way. Physical exercise, therefore, represents an important aid for family caregivers to improve and preserve their quality of life and functional capacity. In this way, physical exercise also helps family caregivers to prolong the provision of care to dependent people, thus contributing to solving a problem that will arise in the future since the number of dependent people is increasing and the life expectancy of this population is increasing [1,2].

Most of the reviewed studies focused on the mental health benefits of caregivers, with fewer also referring to the benefits of physical health, quality of life and functional capacity. There is therefore a need to increase the number of investigations in which the physical benefits of these interventions are also analyzed, since the physical well-being of family caregivers is also affected by the provision of care and influences their quality of life and functional capacity [6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13].

Although the benefits of physical exercise programs are well-documented, family caregivers often face numerous barriers to participation. The primary barriers or limitations are time and place, since these caregivers are unable to be away from home for a long time due to their caregiving responsibilities [43]. In this review, interventions in which physical exercise was performed at home without these barriers were analyzed [26,27,28,30,31,32,33,34,36,37].

In the study conducted by Lin et al. [30], a physical activity intervention was implemented in family caregivers through an application for mobile phones, so that time and place were no longer a limitation as each caregiver could individually adapt the place and time in which to perform the activity. The authors suggest that social support functions as a key mechanism for promoting health improvement.

Madruga et al. [25] take a closer look at how doing physical exercise at home might affect how burdened caregivers feel. As reported in their study, subjective caregiver burden represents a significant barrier to engaging in physical activity. However, the authors concluded that exercising at home can positively influence these symptoms, emphasizing that mental health challenges may hinder participation in physical exercise programs among family caregivers.

In another study, Castro et al. [32] examined adherence to home-based exercise programs among caregivers and reported encouraging results. The authors concluded that, in addition to performing physical exercises from home, constant contact with health professionals reduces stress and further increases the level of adherence to physical exercise programs. Similar findings were reported by Gary et al. [40] in the study analyzed in this review, in which they compared the results of family caregivers who performed physical exercise with family caregivers who received psychoeducation talks in addition to exercise. Their results showed that the group that combined exercises with psychoeducation obtained better health outcomes since the benefits of psychoeducation sessions in mental health increased adherence to the physical exercise intervention, and this in turn also produced benefits in mental health.

Other studies analyzed, such as that by Farran et al. [39], also relate adherence to physical exercise programs from home with socialization, concluding that the lack of socialization in this type of intervention was one of the main causes of dropout in the participants of their study.

This type of social isolation was also evident during the COVID-19 pandemic, when telemedicine and telerehabilitation emerged as practical and effective alternatives for remotely managing various health conditions [44]. In this context, online interventions delivered via videoconferencing represent a promising approach to enhance participation and adherence among family caregivers [45], offering a flexible format that can be adapted to home-based settings.

Future studies should explore the use of telerehabilitation, as it would allow family caregivers to carry out online physical exercise programs from home, without having to neglect the dependent person and adapting to schedules. In addition, telerehabilitation allows a professional to supervise the exercises and ongoing feedback between professionals and caregivers. These online exercise programs could also be delivered in groups formats, increasing the socialization of family caregivers, thus reducing the dropout rate and increasing adherence.

This review has several limitations, such as the small sample size of some of the studies analyzed. Another limitation is the dropout rate in some of the studies, which can interfere with the results, so future research should be carried out in which interventions are more accessible and enjoyable for caregivers. Another limitation is the absence of a meta-analysis, as this review was restricted to a qualitative analysis of the evidence, so as a future perspective, research should be carried out accompanied by meta-analysis.

Finally, a further limitation is that all the studies included in this review were RCTs as they provide the most accurate evidence, thus, incorporating other study designs in future reviews could provide additional insights and a more comprehensive understanding of the topic.

The main clinical implication of this review is that family caregivers of dependent older adults may enhance their quality of life and functional capacity, which would improve the quality and sustainability of the care they provide. Experts in physical exercise could implement and supervise online exercise programs for this population, thereby facilitating participation and promoting long-term adherence.

5. Conclusions

Physical exercise appears to be effective in improving the physical and mental health of family caregivers, as well as enhancing their quality of life and functional capacity. Future research should explore how the use of new technologies can make interventions more accessible to family caregivers, thereby increasing participation and adherence.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/healthcare13101196/s1, S1. Summary of the study characteristics and main results. S2. Search strategy.

Author Contributions

A.B.-V. is the principal investigator, contributed to the conceptualization, methodology investigation, resources and writing—original draft preparation of the study. E.A.-L. contributed to the development of the protocol, formal analysis, validation, investigation and supervision. J.J.G.-G. contributed to the validation, formal analysis, investigation and supervision and he is the correspondence author. C.R.-B. contributed to the writing—review and editing, software, data curation and project administration. C.B.-U. contributed to conceptualization, methodology, investigation, writing—review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data from the present investigation are available by contacting the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- United Nations. World Population Prospects 2024: Summary of Results|Population Division. 2024. Available online: https://www.un.org/development/desa/pd/content/world-population-prospects-2024-summary-results-0 (accessed on 19 February 2025).

- Fortin, M.; Bravo, G.; Hudon, C.; Vanasse, A.; Lapointe, L. Prevalence of Multimorbidity Among Adults Seen in Family Practice. Ann. Fam. Med. 2005, 3, 223–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bustillo, M.L.; Gómez-Gutiérrez, M.; Guillén, A.I.; Bustillo, M.L.; Gómez-Gutiérrez, M.; Guillén, A.I. Los cuidadores informales de personas mayores dependientes: Una revisión de las intervenciones psicológicas de los últimos diez años. Clínica Y Salud 2018, 29, 89–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camarena, J.M.T.; Blanco, M.A.H.; Sansano, N.D.; Canut, M.T.L.; Aran, L.R.; Llobet, M.P. Intervenciones enfermeras para disminuir la sobrecarga de cuidadores informales. Revisión sistemática de ensayos clínicos. Enfermería Global 2022, 21, 562–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casado-Mejía, R.; Ruiz-Arias, E. Estrategias de provisión de cuidados familiares a personas mayores dependientes. Index. Enfermería. 2013, 22, 142–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, C.; Balamurali, T.B.S.; Selwood, A.; Livingston, G. A systematic review of intervention studies about anxiety in caregivers of people with dementia. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2007, 22, 181–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, H.M.; Chuang, D.M.; Yang, F.; Yang, Y.; Liu, W.M.; Liu, L.H.; Tian, H.M. Prevalence and determinants of depression in caregivers of cancer patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine 2018, 97, e11863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaracz, K.; Grabowska-Fudala, B.; Górna, K.; Kozubski, W. Caregiving burden and its determinants in Polish caregivers of stroke survivors. Arch. Med. Sci. 2014, 10, 941–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthews, B.A. Role and gender differences in cancer-related distress: A comparison of survivor and caregiver self-reports. Oncol. Nurs. Forum. 2003, 30, 493–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, A.J.; Ferguson, D.W.; Gill, J.; Paul, J.; Symonds, P. Depression and anxiety in long-term cancer survivors compared with spouses and healthy controls: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2013, 14, 721–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A Price, M.; Butow, P.N.; Costa, D.S.J.; King, M.T.; Aldridge, L.J.; E Fardell, J.; DeFazio, A.; Webb, P.M. Prevalence and predictors of anxiety and depression in women with invasive ovarian cancer and their caregivers. Med. J. Australia 2010, 193 (Suppl. 5), S52–S57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, S.D.; Girgis, A.; Descallar, J.; Levesque, J.V.; Jones, B. Partners’ and Caregivers’ Psychological and Physical Adjustment to Cancer Within the First Five Years Post Survivor Diagnosis. 2014. Available online: https://research.monash.edu/en/publications/partners-and-caregivers-psychological-and-physical-adjustment-to- (accessed on 22 January 2025).

- Pinquart, M.; Sörensen, S. Differences between caregivers and noncaregivers in psychological health and physical health: A meta-analysis. Psychol. Aging. June 2003, 18, 250–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallagher-Thompson, D.; Coon, D.W. Evidence-based psychological treatments for distress in family caregivers of older adults. Psychol. Aging. 2007, 22, 37–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Northouse, L.L.; Katapodi, M.C.; Song, L.; Zhang, L.; Mood, D.W. Interventions with family caregivers of cancer patients: Meta-analysis of randomized trials. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2010, 60, 317–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.Y.; Kwan, R.Y.C.; Leung, A.Y.M. Factors associated with the risk of cardiovascular disease in family caregivers of people with dementia: A systematic review. J. Int. Med. Res. 2019, 48, 0300060519845472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubbert, P.M. Physical activity and exercise: Recent advances and current challenges. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2002, 70, 526–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization 2020 Guidelines on Physical Activity and Sedentary Behaviour. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33239350/ (accessed on 19 February 2025).

- Lee, I.-M.; Shiroma, E.J.; Lobelo, F.; Puska, P.; Blair, S.N.; Katzmarzyk, P.T.; Kahlmeier, S. Effect of physical inactivity on major non-communicable diseases worldwide: An analysis of burden of disease and life expectancy. Lancet 2012, 380, 219–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- I Mishra, S.; Aziz, N.M.; Scherer, R.W.; Baquet, C.R.; Berlanstein, D.R.; Geigle, P.M. Exercise interventions on health-related quality of life for cancer survivors. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2012, 2012, CD007566. [Google Scholar]

- Epps, F.; To, H.; Liu, T.T.; Karanjit, A.; Warren, G. Effect of Exercise Training on the Mental and Physical Well-Being of Caregivers for Persons Living With Chronic Illnesses: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Appl. Gerontol. 2021, 40, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baik, D.; Song, J.; Tark, A.; Coats, H.; Shive, N.; Jankowski, C. Effects of Physical Activity Programs on Health Outcomes of Family Caregivers of Older Adults with Chronic Diseases: A Systematic Review. Geriatr. Nursing. 2021, 42, 1056–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksen, M.B.; Frandsen, T.F. The impact of patient, intervention, comparison, outcome (PICO) as a search strategy tool on literature search quality: A systematic review. J. Med. Libr. Assoc. 2018, 106, 420–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madruga, M.; Gozalo, M.; Prieto, J.; Rohlfs Domínguez, P.; Gusi, N. Effects of a home-based exercise program on mental health for caregivers of relatives with dementia: A randomized controlled trial. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2021, 33, 359–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Connell, C.M.; Janevic, M.R. Effects of a telephone-based exercise intervention for dementia caregiving wives: A randomized controlled trial. J. Appl. Gerontol. 2009, 28, 171–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim J yeon Tak, S.H.; Lee, J.; Choi, H. Effects of Physical Exercise Program for Older Family Caregivers of Persons With Dementia. Am. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. Other Dement. 2023, 38, 15333175231178384. [Google Scholar]

- Lök, N.; Bademli, K.; Lök, S. The effect of a physical activity intervention on burden and healthy lifestyle behavior in family caregivers of patients with schizophrenia: A randomized controlled trial. Arch. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2023, 42, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A Hives, B.; Buckler, E.J.; Weiss, J.; Schilf, S.; Johansen, K.L.; Epel, E.S.; Puterman, E. The Effects of Aerobic Exercise on Psychological Functioning in Family Caregivers: Secondary Analyses of a Randomized Controlled Trial. Ann. Behav. Medicine. 2021, 55, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.Y.; Zhang, L.; Yoon, S.; Zhang, R.; Lachman, M.E. A Social Exergame Intervention to Promote Physical Activity, Social Support, and Well-Being in Family Caregivers. Gerontologist 2023, 63, 1456–1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puterman, E.; Weiss, J.; Lin, J.; Schilf, S.; Slusher, A.L.; Johansen, K.L.; Epel, E.S. Aerobic exercise lengthens telomeres and reduces stress in family caregivers: A randomized controlled trial—Curt Richter Award Paper 2018. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2018, 98, 245–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, C.M.; Wilcox, S.; O’Sullivan, P.; Baumann, K.; King, A.C. An exercise program for women who are caring for relatives with dementia. Psychosom. Med. 2002, 64, 458–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz, C.K.; Aşiret, G.D.; Çetinkaya, F.; OludaĞ, G.; Kapucu, S. Effect of progressive muscle relaxation on the caregiver burden and level of depression among caregivers of older patients with a stroke: A randomized controlled trial. Jpn. J. Nurs. Sci. 2019, 16, 202–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montero-Cuadrado, F.; Galán-Martín, M.Á.; Sánchez-Sánchez, J.; Lluch, E.; Mayo-Iscar, A.; Cuesta-Vargas, Á. Effectiveness of a Physical Therapeutic Exercise Programme for Caregivers of Dependent Patients: A Pragmatic Randomised Controlled Trial from Spanish Primary Care. Int. J. Env. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prieto-Prieto, J.; Madruga, M.; Adsuar, J.C.; González-Guerrero, J.L.; Gusi, N. Effects of a Home-Based Exercise Program on Health-Related Quality of Life and Physical Fitness in Dementia Caregivers: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Int. J. Env. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 9319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, A.C.; Baumann, K.; O’Sullivan, P.; Wilcox, S.; Castro, C. Effects of moderate-intensity exercise on physiological, behavioral, and emotional responses to family caregiving: A randomized controlled trial. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2002, 57, M26–M36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flanagan, J.; Post, K.; Hill, R.; DiPalazzo, J. Feasibility of a Nurse Coached Walking Intervention for Informal Dementia Caregivers. West. J. Nurs. Res. 2022, 44, 466–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirano, A.; Suzuki, Y.; Kuzuya, M.; Onishi, J.; Ban, N.; Umegaki, H. Influence of regular exercise on subjective sense of burden and physical symptoms in community-dwelling caregivers of dementia patients: A randomized controlled trial. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2011, 53, e158–e163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farran, C.J.; Etkin, C.D.; Eisenstein, A.; Paun, O.; Rajan, K.B.; Sweet, C.M.C.; McCann, J.J.; Barnes, L.L.; Shah, R.C.; Evans, D.A. Effect of Moderate to Vigorous Physical Activity Intervention on Improving Dementia Family Caregiver Physical Function: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Alzheimers Dis. Parkinsonism. 2016, 6, 253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gary, R.; Dunbar, S.B.; Higgins, M.; Butts, B.; Corwin, E.; Hepburn, K.; Butler, J.; Miller, A.H. An Intervention to Improve Physical Function and Caregiver Perceptions in Family Caregivers of Persons With Heart Failure. J. Appl. Gerontol. 2020, 39, 181–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loi, S.M.; Gaffy, E.; Malta, S.; Russell, M.A.; Williams, S.; Ames, D.; Hill, K.D.; Batchelor, F.; Cyarto, E.V.; Haines, T.; et al. Effects of physical activity on depressive symptoms in older caregivers: The IMPACCT randomized controlled trial. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2024, 39, e6058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RoB 2: A Revised Tool for Assessing Risk of Bias in Randomized Trials. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31462531/ (accessed on 29 March 2025).

- Oliver, D.P.; Patil, S.; Benson, J.J.; Gage, A.; Washington, K.; Kruse, R.L.; Demiris, G. The Effect of Internet Group Support for Caregivers on Social Support, Self-Efficacy, and Caregiver Burden: A Meta-Analysis. Telemed. E Health 2017, 23, 621–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernal-Utrera, C.; Anarte-Lazo, E.; De-La-Barrera-Aranda, E.; Fernandez-Bueno, L.; Saavedra-Hernandez, M.; Gonzalez-Gerez, J.J.; Serrera-Figallo, M.A.; Rodriguez-Blanco, C. Perspectives and Attitudes of Patients with COVID-19 toward a Telerehabilitation Programme: A Qualitative Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 7845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Bueno, L.; Torres-Enamorado, D.; Bravo-Vazquez, A.; Rodriguez-Blanco, C.; Bernal-Utrera, C. Technological Innovations to Support Family Caregivers: A Scoping Review. Healthcare 2024, 12, 2350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).