Between Care and Mental Health: Experiences of Managers and Workers on Leadership, Organizational Dimensions, and Gender Inequalities in Hospital Work

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design and Approach

2.2. Participants and Sampling

2.3. Data Collection Procedure

2.4. Ethical Considerations

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. The Role of Leadership

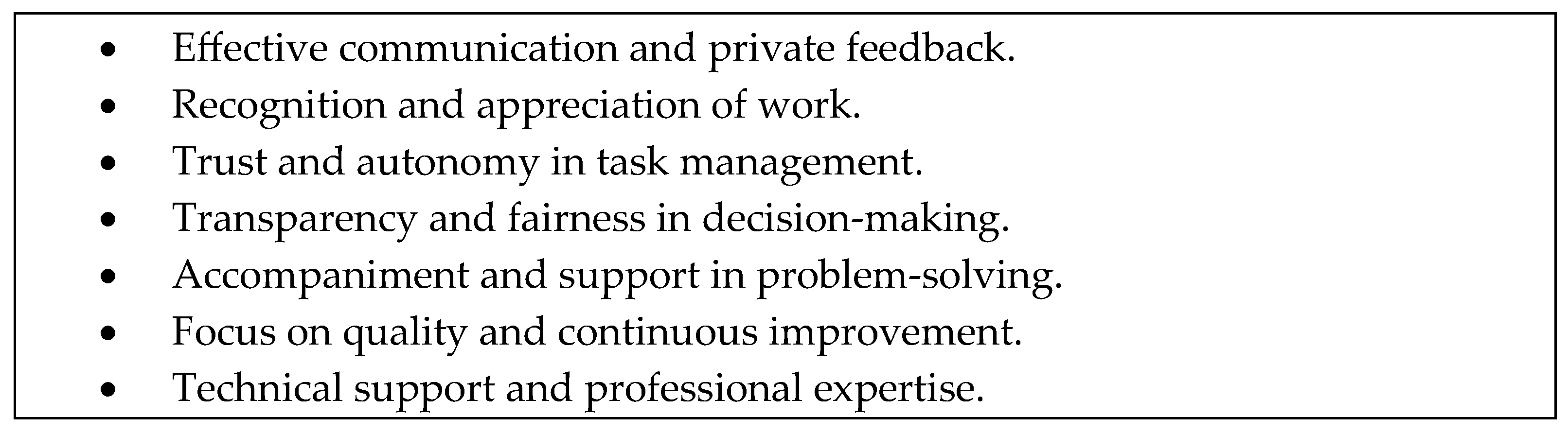

3.1.1. Constructive Leadership: Expressions and Practices

“A good leader first has to communicate with his workers… Know how to listen to the workers…”[Interview3—Administrative worker, man, subordinate].

“Good leadership, for example, would be a boss who supports you, who responds, who is with you, who gives you the tools, who listens to you, and who can respond or who can support you, give you options or alternatives, or teach you in case you need something”[Interview12—Nurse, woman, manager].

3.1.2. Destructive Leadership: Expressions and Practices

“…distant, directing from his office and only delivering orders without getting actively involved, but waiting for the occurrence of errors to punish workers”[Interview3—Administrative worker, man, subordinate].

“There were no solutions… and the leadership was hiding… when they were mistreating us, and they were hiding in their office, locked up”[Interview25—Administrative worker, woman, subordinate].

“…and she starts yelling at me and says, ‘Why do you have to give a reason to that manager who comes to get into our unit and give her opinion about the patients and she has no reason to be getting involved in the treatment, in the diagnosis?’”[Interview36—Nurse, woman, manager].

“When it comes to resolving some conflicts or conversations that are somewhat uncomfortable, he avoids them. When he has to give feedback on something that may be uncomfortable, for some mistake that some physician on his team has made, he does not have those difficult conversations”[Interview49—Kinesiologist, man, manager].

3.1.3. The Role of Leadership in Perceived Psychological Support and Safety

“Knowing that my leader, in this case, the nurse, the shift manager, is there in the good times and in the hard times; and I am going to be able to turn to her”[Interview17—Nurse Technician, man, subordinate].

“Look, for me, leadership has to be a person who is an example, who is a motivator as well, and who has emotional self-management.”[Interview29—Physician, woman, manager].

3.2. Role Stress and Recognition

3.2.1. Role Stress

“If I am already missing an extra shift or I cannot come to do it, one says to the colleague: ‘Could you do this extra shift that I have assigned?’ Then one tells the boss: ‘Boss, I cannot come to do an extra shift; I am going to get this person to do it.’ ‘Yeah, that is fine.’ Then she deletes it from the system and has the power to delete it from the system” [Interview9—Nurse Technician, woman, subordinate].

“Now, what’s wrong with me? When the doctors, nurses, kinesiologists, and psychologists see me, they say, ‘Oh [Name omitted], I have a case for you’, and they bombard me with information or write me little notes and leave them in the office. The same goes for patients who feel they haven’t been referred to the doctor; they come knocking on the door saying, ‘Hello, I need to talk to you. Please, please, please, I need to talk to you. So there’s a structure for everyone else, but it doesn’t work for me”.[Interview 57—Social Worker, Woman, subordinate].

“It is important that the shift manager is implemented so that colleagues are not taken out of their functions to do other administrative functions”[Interview44—Nurse, woman, manager].

3.2.2. Recognition

- Formality of recognition: a distinction is made between formal recognition (institutionalized actions such as merit notes) and informal recognition (spontaneous thanks from bosses, colleagues, or patients);

- Source of recognition: various sources of recognition are identified, including managers, peers, and health system users.

“Yes, there are merit marks that come for care management, generally, but that is more than what your boss has, such that goes and makes you. No, it is more for the patients themselves filling out forms sometimes”[Interview30—Nurse, woman, subordinate].

- Recognition of workers: the importance of highlighting individual effort and contributions is appreciated, but it is recognized that this occurs in an informal and unsystematic manner;

- Lack of recognition for management: there is a perception of a lack of institutional protection since management receives little recognition from the organization;

- The imbalance between effort and reward in leadership roles: it is mentioned that there are no economic incentives or job stability for those who assume leadership responsibilities.

“At the moment, no other recognition. I mean, you know, here in the public system, we are managed by a single salary scale, basically, our grade, and I still have exactly the same grade as when I entered, and I was a clinical kinesiologist… So, obviously, being in charge of 30 people is not easy at all. Because of the level of decision-making and everything else, there is also merit at an economic level, but that has not materialized for the moment”[Interview49—Kinesiologist, man, manager].

3.2.3. The Impact of Role Stress and Recognition on Mental Health

- Role stress: work overload, ambiguity in the distribution of functions, and conflict between incompatible demands generate high stress levels and emotional exhaustion. Both subordinates and managers report that the lack of clarity in the assignment of roles and excessive workload contribute to fatigue and deterioration of mental health.

“[Overload is explained by]… someone did not come, someone was absent, so what does the shift manager have to do in this case? Restructure with what he has, and that is when, suddenly, certain problems may arise because some areas will be more lacking than others. So, the work that I do with three, I will have to do with two, or if there are two, I will have to do it alone, and that can put a little more pressure on me”[Interview33—Nurse, woman, manager];

- Recognition: workers’ motivation and commitment are strengthened when their efforts are valued. However, the absence of formal recognition by the organization generates frustration and a sense of inequity, affecting job satisfaction and team morale.

“Mostly, we receive recognition from our users. The meaning of being given candy or chocolate or saying thank you is like gratification, but institutionally, no”[Interview31—Nurse Technician, man, subordinate].

3.3. Leadership and Gender as a Dimension of Social Inequality

- The perception of gender in the work environment and conflicts in mostly female teams: while some female workers recognize progress in protection against harassment and discrimination, some men perceive that the increasing regulation around gender equity has generated more significant conflict and competition in teams;

- Impact of maternity on employment decisions: maternity influences women’s career paths, determining their choice of positions and preference for certain institutions. Adjustments in work shifts are also needed. However, women workers perceive that organizational support in these circumstances is limited;

- Difficulties reconciling work and family life: working mothers report that exercising their rights, such as maternity leave or shift changes, can generate conflicts with their teams and work organization, contributing to a feeling of vulnerability and a lack of institutional support.

- Feminization of the sector and perceptions of the work environment: while some managers, especially women, consider that the high female presence contributes to a better understanding of the health needs of the population served, some men associate the predominance of women with a work environment marked by conflict and rumors;

- Difficulties of work–family reconciliation in leadership positions: female managers with children face problems like those of their female subordinates in reconciling work and family. However, they report that these situations can generate tensions within the team, especially when they involve the redistribution of shifts or adjustments in the workload;

- Persistence of gender stereotypes in access to leadership: despite the feminization of the sector, gender stereotypes continue to influence the perception of leadership, resulting in a preference for men in strategic or senior management roles.

Gender Inequalities in Access to and Exercise of Leadership and Their Effect on Well-Being

- Double workload and work-family reconciliation: women in managerial and operational positions face difficulties reconciling their work responsibilities with family demands. The need to change shifts or access maternity benefits can generate tensions in teams and a perception of disadvantage among those who must redistribute tasks;

- Gender perceptions of leadership: despite the high presence of women in the sector, leadership is still associated with traditionally male characteristics. This reinforces a structure where men occupy strategic positions while women are relegated to less recognized roles;

- Impact on mental health: the perception that women must constantly prove their competence in an environment where leadership remains masculinized generates additional pressure, increasing stress and burnout.

“There is also a social role in between gender stereotypes, and that influences. In other words, we have a culture in which we still think of men when we talk about leadership”[Interview54—Administrative Worker, man, manager].

“Well, the only thing that really occurs to me is that since I am on maternity leave, which is basically the protection of the child up to the age of two, I have one hour of breastfeeding. So, uh, it was conflictive. In a low, low key, conflictive way, the fact that I must leave earlier and arrive later because that means that the person on duty has to stay longer”[Interview56—Nurse, woman, subordinate].

4. Discussion

4.1. Synthesis of the Findings and Their Relation to This Study’s Objective

4.2. Study Contributions

- A comprehensive approach to health leadership: in contrast to previous research focused on service quality and organizational efficiency, this study examines the impact of leadership on workers’ mental health and well-being. It confirms that leadership can act as a protective factor or as a psychosocial risk, depending on its practices. Leadership that promotes trust and fairness generates healthier work environments, while negative leadership styles increase emotional burnout. Thus, leaders play a central role in fostering psychosocial safety, which, in turn, has been identified as a key dimension in fostering a high-functioning healthcare team culture [55];

- Interconnection between leadership, recognition, and role stress: leadership does not operate in isolation but is linked to organizational conditions that affect the work experience of workers. Firstly, the lack of formal recognition and incentives generates demotivation and emotional exhaustion, which aligns with the effort–reward imbalance model and mental health problems [51]. Secondly, there are critical dimensions of role clarity that negatively impact workers’ mental health, reinforcing the need to improve clarity in assigning roles within public hospitals;

- Gender perspective in hospital leadership: gender inequalities in a highly feminized sector are made visible. The findings show that women face more significant barriers to accessing leadership positions; female leadership is evaluated with more demanding criteria; and work–family reconciliation represents a considerable challenge for women, affecting their well-being and generating tensions in teams. This reinforces the urgency of implementing organizational policies that promote gender equity in leadership and facilitate work–family reconciliation. This is especially important in light of previous evidence showing the advantages for healthcare organizations of having women in leadership positions: ‘women leaders’ positive influence on six areas of impact: (1) financial performance, risk, and stability, (2) innovation, (3) engagement with ethical initiatives, (4) health, (5) organizational culture and climate outcomes, and (6) influence on other women’s careers and aspirations [41];

- Implications for hospital management and public policy: the findings directly impact hospital leadership management and occupational health policy design. Organizational leadership training is required to improve the management of well-being and equity in work teams. According to the effort–reward imbalance theory [51], formal recognition mechanisms must be implemented to prevent the perception of unrewarded effort. The distribution of roles and workloads should be reviewed to mitigate role stress and improve operational efficiency in hospitals.

4.3. Limitations of the Study

4.4. Implications and Projections for Prevention

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Guo, M.; Khassawneh, O.; Mohammad, T.; Pei, X. When Leadership Goes Awry: The Nexus between Tyrannical Leadership and Knowledge Hiding. J. Knowl. Manag. 2024, 28, 1096–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montano, D.; Schleu, J.E.; Hüffmeier, J. A Meta-Analysis of the Relative Contribution of Leadership Styles to Followers’ Mental Health. J. Leadersh. Organ. Stud. 2023, 30, 90–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, S.; Wong, J.Y.H.; Wang, T.; An, B.; Fong, D.Y.T. Psychological Distress as a Mediator between Workplace Violence and Turnover Intention with Caring for Patients with COVID-19. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1321957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansoleaga, E.; Ahumada, M.; Cruz, A.G.-S. Association of Workplace Bullying and Workplace Vulnerability in the Psychological Distress of Chilean Workers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 4039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoss, M.K. Job Insecurity: An Integrative Review and Agenda for Future Research. J. Manag. 2017, 43, 1911–1939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, D.; Giga, S.; Hoel, H. Organisational Causes of Workplace Bullying. In Bullying and Harassment in the Workplace: Developments in Theory, Research and Practice; Einarsen, S., Hoel, H., Zapf, D., Cooper, C.L., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2011; pp. 267–281. [Google Scholar]

- Berr, X.D.; Cardarelli, A.M.; Moreno, E.A.; Cifuentes, J.P.T. Violencia de Género En El Trabajo En Chile. Un Campo de Estudio Ignorado. Cienc. Trab. 2017, 19, 42–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milner, A.; Scovelle, A.; King, T.; Marck, C.; McAllister, A.; Kavanagh, A.; Shields, M.; Török, E.; O’Neil, A. Gendered Working Environments as a Determinant of Mental Health Inequalities: A Protocol for a Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forssberg, K.S.; Vänje, A.; Parding, K. Bringing in Gender Perspectives on Systematic Occupational Safety and Health Management. Saf. Sci. 2022, 152, 105776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilodeau, J.; Marchand, A.; Demers, A. Psychological Distress Inequality between Employed Men and Women: A Gendered Exposure Model. SSM-Popul. Health 2020, 11, 100626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estancial, C.; de Azevedo, R.; Goldbaum, M.; Barros, M. Psychotropic Use Patterns: Are There Differences between Men and Women? PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0207921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, C.; Pereira, A. Exposure to Psychosocial Risk Factors in the Context of Work: A Systematic Review. Rev. Saude Publica 2016, 50, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biswas, A.; Tiong, M.; Irvin, E.; Zhai, G.; Sinkins, M.; Johnston, H.; Yassi, A.; Smith, P.M.; Koehoorn, M. Gender and Sex Differences in Occupation-Specific Infectious Diseases: A Systematic Review. Occup. Environ. Med. 2024, 81, 425–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flynn, C.; Watson, C.; Patton, D.; O’Connor, T. The Impact of Burnout on Paediatric Nurses’ Attitudes about Patient Safety in the Acute Hospital Setting: A Systematic Review. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2024, 78, e82–e89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hill, J.E.; Harris, C.; Danielle, L.C.; Boland, P.; Doherty, A.J.; Benedetto, V.; Gita, B.E.; Clegg, A.J. The Prevalence of Mental Health Conditions in Healthcare Workers during and after a Pandemic: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J. Adv. Nurs. 2022, 78, 1551–1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narbona, K.; Páez, A.; Tonelli, P. Precariedad Laboral y Modelo Productivo En Chile; FundaciónSol: Santiago, Chile, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Quesada-Puga, C.; Izquierdo-Espin, F.J.; Membrive-Jiménez, M.J.; Aguayo-Estremera, R.; Cañadas-De La Fuente, G.A.; Romero-Béjar, J.L.; Gómez-Urquiza, J.L. Job Satisfaction and Burnout Syndrome among Intensive-Care Unit Nurses: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Intensive Crit. Care Nurs. 2024, 82, 103660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Superintendencia de Seguridad Social. Informe de Enfermedades Profesionales; Superintendencia de Seguridad Social: Santiago, Chile, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Pan American Health Organization (PAHO). The COVID-19 HEalth caRe wOrkErs Study (HEROES); Pan American Health Organization: Washinton, DC, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Padilla Fortunatti, C.; Palmeiro-Silva, Y.K. Effort-Reward Imbalance and Burnout among ICU Nursing Staff: A Cross-Sectional Study. Nurs. Res. 2017, 66, 410–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colindres, C.V.; Bryce, E.; Coral-Rosero, P.; Ramos-Soto, R.M.; Bonilla, F.; Yassi, A. Effect of Effort-Reward Imbalance and Burnout on Infection Control among Ecuadorian Nurses. Int. Nurs. Rev. 2018, 65, 190–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernal, D.; Campos-Serna, J.; Tobias, A.; Vargas-Prada, S.; Benavides, F.G.; Serra, C. Work-Related Psychosocial Risk Factors and Musculoskeletal Disorders in Hospital Nurses and Nursing Aides: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2015, 52, 635–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballester, A.R.; García, A.M. Asociación Entre La Exposición Laboral a Factores Psicosociales y La Existencia de Trastornos Musculoesqueléticos En Personal de Enfermería: Revisión Sistemática y Meta-Análisis. Rev. Esp. Salud. Pública 2017, 91, e201704028. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, C.; Zou, J.; Ma, H.; Zhong, Y. Role Stress, Occupational Burnout and Depression among Emergency Nurses: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int. Emerg. Nurs. 2024, 72, 101387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padmanabhanunni, A.; Pretorius, T.B.; Khamisa, N. The Role of Resilience in the Relationship between Role Stress and Psychological Well-Being during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Cross-Sectional Study. BMC Psychol. 2023, 11, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Women in Global Health. The State of Women and Leadership in Global Health; Women in Global Health: Washington, DC, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Habib, R.R.; Halwani, D.A.; Mikati, D.; Hneiny, L. Sex and Gender in Research on Healthcare Workers in Conflict Settings: A Scoping Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- PNUD. Género en el Sector Salud: Feminización y Brechas Laborales; PNUD: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- George, A.S.; McConville, F.E.; de Vries, S.; Nigenda, G.; Sarfraz, S.; McIsaac, M. Violence against Female Health Workers Is Tip of Iceberg of Gender Power Imbalances. BMJ 2020, 371, m3546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palma, A.; Ansoleaga, E. Demandas emocionales, violencia laboral y salud mental según género en trabajadores de hospitales públicos chilenos. Psicoperspectivas Individuo Soc. 2022, 21, 55–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palma, A. Indicadores de Problemas de Salud Mental Atendiendo a Desigualdades Sociales y de Género. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad Diego Portales, Santiago, Chile, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Zaghmout, B. Unmasking Toxic Leadership: Identifying, Addressing, and Preventing Destructive Leadership Behaviours in Modern Organizations. Open J. Leadersh. 2024, 13, 244–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Einarsen, S.; Aasland, M.S.; Skogstad, A. Destructive Leadership Behaviour: A Definition and Conceptual Model. Leadersh. Q. 2007, 18, 207–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuchenbaur, M.; Peter, R. Quality of Leadership and Self-Rated Health: The Moderating Role of “Effort-Reward Imbalance”: A Longitudinal Perspective. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 2023, 96, 473–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madsen, I.E.H.; Hanson, L.L.M.; Rugulies, R.; Theorell, T.; Burr, H.; Diderichsen, F.; Westerlund, H. Does Good Leadership Buffer Effects of High Emotional Demands at Work on Risk of Antidepressant Treatment? A Prospective Study from Two Nordic Countries. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2014, 49, 1209–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarado, R.; Ramírez, J.; Lanio, Í.; Cortés, M.; Aguirre, J.; Bedregal, P.; Allel, K.; Tapia-muñoz, T.; Burrone, M.S.; Cuadra-Malinarich, G.; et al. El Impacto de La Pandemia de COVID-19 En La Salud Mental de Los Trabajadores de La Salud En Chile: Datos Iniciales de The Health Care Workers Study. Rev. Médica Chile 2021, 149, 1205–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arias-Ulloa, C.A.; Gómez-Salgado, J.; Escobar-Segovia, K.; García-Iglesias, J.J.; Fagundo-Rivera, J.; Ruiz-Frutos, C. Psychological Distress in Healthcare Workers during COVID-19 Pandemic: A Systematic Review. J. Saf. Res. 2023, 87, 297–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonagh, K.J.; Bobrowski, P.; Hoss, M.A.K.; Paris, N.M.; Schulte, M. The Leadership Gap: Ensuring Effective Healthcare Leadership Requires Inclusion of Women at the Top. Open J. Leadersh. 2014, 3, 20–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okpala, P. Addressing Power Dynamics in Interprofessional Health Care Teams. Int. J. Healthc. Manag. 2020, 14, 1326–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TASKForce Interamericano El Liderazgo de Las Mujeres. En la Salud de las Américas: Por una Gobernanza Sanitaria Paritaria e Inclusiva; TASKForce Interamericano El Liderazgo de Las Mujeres: Washington, DC, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Kalbarczyk, A.; Banchoff, K.; Perry, K.E.; Nielsen, C.P.; Malhotra, A.; Morgan, R. A Scoping Review on the Impact of Women’s Global Leadership: Evidence to Inform Health Leadership. BMJ Glob. Health 2025, 10, e015982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Einarsen, S.; Skogstad, A.; Aasland, M.S. The Nature, Prevalence, and Outcomes of Destrucive Leadership: A Behavioral and Conglomerate Approach. In When Leadership Goes Wrong. Destructive Leadership, Mistakes, and Ethical Failures; Schyns, B., Hansbrough, T., Eds.; Information Age Publishing: Charlotte, NC, USA, 2010; pp. 145–171. [Google Scholar]

- Daly, J.; Jackson, D.; Mannix, J.; Davidson, P.M.; Hutchinson, M. The Importance of Clinical Leadership in the Hospital Setting. J. Healthc. Leadersh. 2014, 6, 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.D.C.; Khiljee, N. Leadership in Healthcare. Anaesth. Intensive Care Med. 2016, 17, 63–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lega, F.; Prenestini, A.; Rosso, M. Leadership Research in Healthcare: A Realist Review. Health Serv. Manag. Res. 2017, 30, 94–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tschannen-Moran, M. Cultivando la confianza ante la adversidad. In Liderazgo en Escuelas de Alta Complejidad Sociocultural; Weinstein, J., Muñoz, G., Eds.; Ediciones Universidad Diego Portales: Santiago, Chile, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches, 3rd ed.; SAGE Publishing: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2013; ISBN 978-1-4129-6556-9. [Google Scholar]

- Valles, M. Técnicas Cualitativas de Investigación Social; Síntesis: Madrid, Spain, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Corbin, J.; Strauss, A. Grounded Theory Research: Procedures, Canons and Evaluative Criteria. Zeitschritf. Für. Soziol. 1990, 19, 418–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, J.; He, J.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Pan, J.; Zhang, X.; Liu, D. Effects of Effort-Reward Imbalance, Job Satisfaction, and Work Engagement on Self-Rated Health among Healthcare Workers. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegrist, J. Adverse Health Effects of High-Effort/Low-Reward Conditions. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 1996, 1, 27–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeinali, Z.; Muraya, K.; Molyneux, S.; Morgan, R. The Use of Intersectional Analysis in Assessing Women’s Leadership Progress in the Health Workforce in LMICs: A Review. Int. J. Health Policy Manag. 2021, 11, 1262–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, J.; Hawkes, S. Overcoming Gender Gaps in Health Leadership. BMJ 2024, 387, q2768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sim, E.; Bierema, L. A Systematic Literature Review of Intersectional Leadership in the Workplace: The Landscape and Framework for Future Leadership Research and Practice to Challenge Interlocking Systems of Oppression. J. Leadersh. Organ. Stud. 2025, 32, 71–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaPlante, R.D.; Ponte, P.R.; Magny-Normilus, C. Essential Elements and Outcomes of Psychological Safety in the Healthcare Practice Setting: A Systematic Review. Appl. Nurs. Res. 2025, 83, 151946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample Characteristics | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Hierarchical Position | Man | Women | Total |

| Managers | 16 | 16 | 32 |

| Subordinates | 10 | 22 | 32 |

| Total | 26 | 38 | 64 |

| Variable | n | % |

| Sex | ||

| Women | 39 | 60.94% |

| Men | 25 | 39.06% |

| Occupational hierarchy | ||

| Managers | 32 | 50% |

| Subordinates | 32 | 50% |

| Setting | ||

| Clinical | 39 | 60.94% |

| Administrative | 25 | 39.06% |

| Professional Category | ||

| Medical | 10 | 15.62% |

| Nursing | 26 | 40.63% |

| Other healthcare professionals | 11 | 17.19% |

| Administrative | 8 | 12.50% |

| Technician | 9 | 14.06% |

| Work Settings | ||

| Intrahospital | 40 | 62.50% |

| Outpatient | 24 | 37.50% |

| Work Unit | ||

| Critical Pacient Unit | 34 | 53.12% |

| Regular Care | 30 | 46.88% |

| Work Schedule | ||

| Daytime | 33 | 51.56% |

| Shift work | 24 | 37.50% |

| Half day | 3 | 4.69% |

| Missing | 4 | 6.25% |

| Variables | M | SD | Minimum | Maximum |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 37.91 | 8.95 | 26.00 | 62.00 |

| Time in the job position (in months) | 89.76 | 64.32 | 3.00 | 252.00 |

| Categories | Subcategories |

|---|---|

| Leadership | Destructive Leadership Constructive leadership |

| Organizational dimensions | Recognition Role stress (overload, conflict, ambiguity) |

| Social inequality | Gender inequality |

| Welfare implications | Discomfort Well-being |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ansoleaga, E.; Ahumada, M.; Soto-Contreras, E.; Vera, J. Between Care and Mental Health: Experiences of Managers and Workers on Leadership, Organizational Dimensions, and Gender Inequalities in Hospital Work. Healthcare 2025, 13, 1144. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13101144

Ansoleaga E, Ahumada M, Soto-Contreras E, Vera J. Between Care and Mental Health: Experiences of Managers and Workers on Leadership, Organizational Dimensions, and Gender Inequalities in Hospital Work. Healthcare. 2025; 13(10):1144. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13101144

Chicago/Turabian StyleAnsoleaga, Elisa, Magdalena Ahumada, Elena Soto-Contreras, and Javier Vera. 2025. "Between Care and Mental Health: Experiences of Managers and Workers on Leadership, Organizational Dimensions, and Gender Inequalities in Hospital Work" Healthcare 13, no. 10: 1144. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13101144

APA StyleAnsoleaga, E., Ahumada, M., Soto-Contreras, E., & Vera, J. (2025). Between Care and Mental Health: Experiences of Managers and Workers on Leadership, Organizational Dimensions, and Gender Inequalities in Hospital Work. Healthcare, 13(10), 1144. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13101144