Mental Health Recovery Process Through Art: An Exploratory Mixed-Methods Multi-Center Study of an Art-Based Community Project

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. The Study

1.1.1. Aim

- (a)

- To examine the impact of participating in the Artistic Couples project and its influence on subjective perceptions of the recovery process in mental health, psychological well-being, and self-stigma.

- (b)

- To explore the experiences, satisfaction and opportunities for participation in the Artistic Couples project among individuals linked to mental health services.

- (c)

- To understand how mental health recovery is perceived and connected to the experiences within the Artistic Couples project.

1.1.2. About the Artistic Couples Project

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

2.2. Recruitment Procedure

2.3. Ethical Considerations

2.4. Data Collection

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sociodemographic Data of Participants

3.2. Qualitative Findings

3.2.1. Artmaking as an Artistic Couple

3.2.2. Social Connections

3.2.3. Understanding Mental Health Recovery

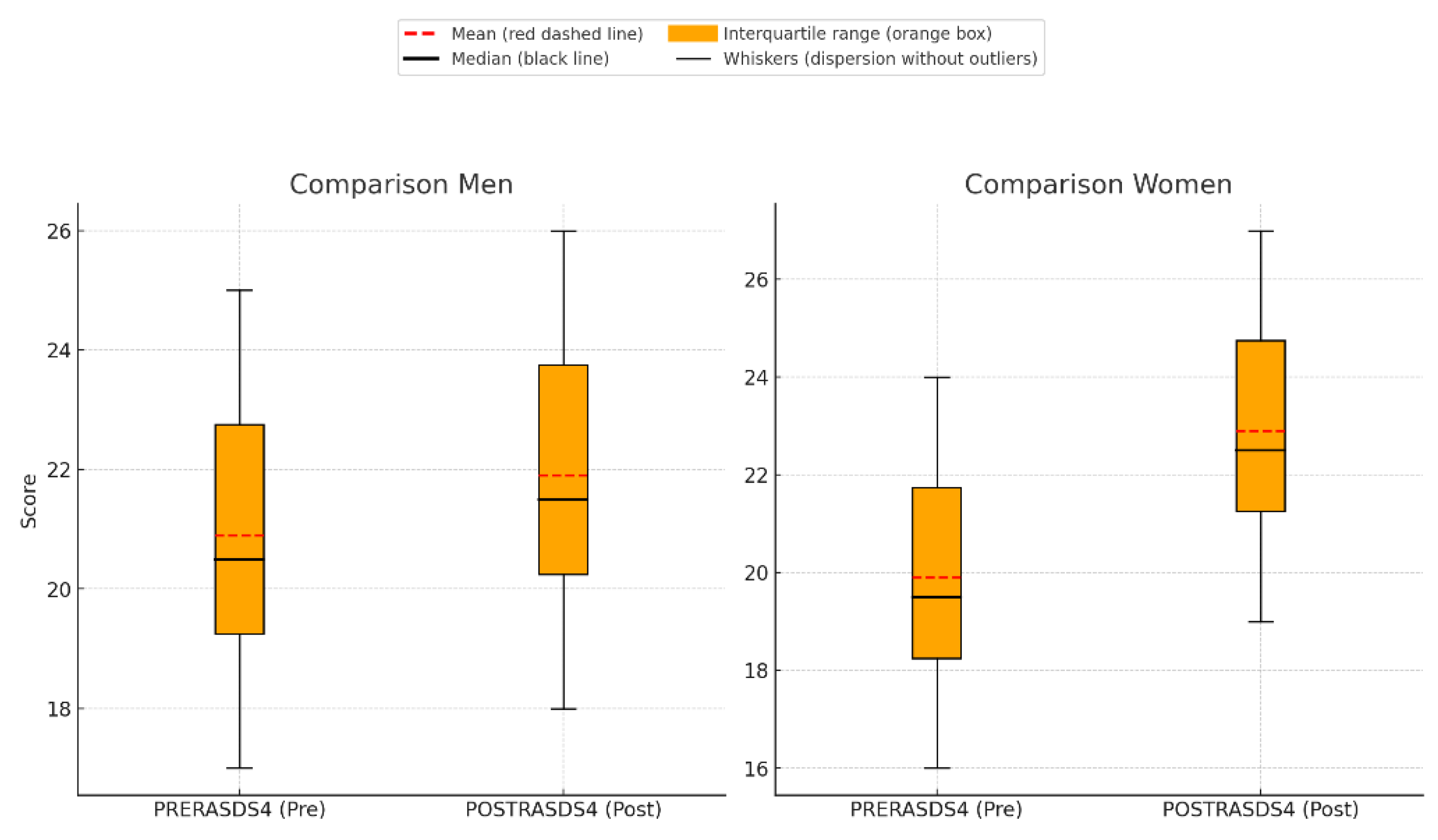

3.3. Quantitative Findings

4. Discussion

4.1. Practical Implications

4.2. Study Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PROMs | Patient-Reported Outcome Measures |

| QPR | Questionnaire about the process of recovery |

| RAS-DS | Recovery Assessment Scale—Domains and Stages |

| EQ-5D | European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions |

| PWB | Ryff Psychological Well-being Scale |

| ISMI | Internalized Stigma of Mental Illness Inventory |

| PREMs | Patient-reported experience measures |

References

- Fancourt, D.; Finn, S. What is the evidence on the role of the arts in improving health and well-being? A scoping review. Health Evid. Netw. Synth. Rep. 2019, 67, 32091683. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/329834 (accessed on 12 February 2025).

- Gómez-Restrepo, C.; Godoy-Casasbuenas, N.; Ortiz-Hernández, N.; Bird, V.; Acosta, M.P.J.; Uribe-Restrepo, J.M.; Sarmiento, B.A.M.; Steffen, M.; Priebe, S. Role of the arts in the life and mental health of young people that participate in artistic organizations in Colombia: A qualitative study. BMC Psychiatry 2022, 22, 757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hui, A.; Stickley, T.; Stubley, M.; Baker, F. Project eARTh: Participatory arts and mental health recovery, a qualitative study. Perspect. Public Health 2019, 139, 296–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Transforming Mental Health for All—Executive Summary; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240050860 (accessed on 12 February 2025).

- Daykin, N.; de Viggiani, N.; Pilkington, P.; Moriarty, Y. Music making for health, well-being and behaviour change in youth justice settings: A systematic review. Health Promot. Int. 2013, 28, 197–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Vaart, G. Insights and inspiration from explorative research into the impacts of a community arts project. In Co-Creativity and Engaged Scholarship; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 205–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tew, J.; Ramon, S.; Slade, M.; Bird, V.; Melton, J.; Le Boutillier, C. Social factors and recovery from mental health difficulties: A review of the evidence. Br. J. Soc. Work 2012, 42, 443–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nitzan, A.; Orkibi, H. “We’re All in the Same Boat”—The Experience of People with Mental Health Conditions and Non-clinical Community Members in Integrated Arts-Based Groups. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 661831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stickley, T.; Hui, A. Social prescribing through arts on prescription in a UK city: Participants’ perspectives (part 1). Public Health 2012, 126, 574–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrigan, P.W.; Watson, A.C. Understanding the impact of stigma on people with mental illness. World Psychiatry 2002, 1, 16–20. [Google Scholar]

- Anthony, W.A. Recovery from mental illness: The guiding vision of the mental health service system in the 1990s. Psychosoc. Rehabil. J. 1993, 16, 11–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roe, D.; Mashiach-Eizenberg, M.; Lysaker, P.H. The relation between objective and subjective domains of recovery among persons with schizophrenia-related disorders. Schizophr. Res. 2011, 131, 133–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepherd, G.; Boardman, J.; Slade, M. Making Recovery a Reality; Sainsbury Centre for Mental Health: London, UK, 2008; Available online: https://www.researchintorecovery.com/files/SCMH%202008%20Making%20recovery%20a%20reality.pdf (accessed on 12 February 2025).

- Slade, M.; Amering, M.; Farkas, M.; Hamilton, B.; O’Hagan, M.; Panther, G.; Perkins, R.; Shepherd, G.; Tse, S.; Whitley, R. Uses and abuses of recovery: Implementing recovery-oriented practices in mental health systems. World Psychiatry 2014, 13, 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacob, S.; Munro, I.; Taylor, B.J. Mental health recovery: Lived experience of consumers, carers, and nurses. Contemp. Nurse 2015, 50, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leamy, M.; Foye, U.; Hirrich, A.; Bjørgen, D.; Silver, J.; Simpson, A.; Ellis, M.; Johan-Johanson, K. A systematic review of measures of the personal recovery orientation of mental health services and staff. Int. J. Ment. Health Syst. 2023, 17, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leamy, M.; Bird, V.; Le Boutillier, C.; Williams, J.; Slade, M. Conceptual framework for personal recovery in mental health: Systematic review and narrative synthesis. Br. J. Psychiatry 2011, 199, 445–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Weeghel, J.; van Zelst, C.; Boertien, D.; Hasson-Ohayon, I. Conceptualizations, assessments, and implications of personal recovery in mental illness: A scoping review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Psychiatr. Rehabil. J. 2019, 42, 169–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bird, V.; Leamy, M.; Tew, J.; Boutillier, C.L.; Williams, J.; Slade, M. Fit for purpose? Validation of a conceptual framework for personal recovery with current mental health consumers. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 2014, 48, 644–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogel, J.S.; Bruins, J.; Halbersma, L.; Lieben, R.J.; De Jong, S.; Van Der Gaag, M.; Castelein, S. Measuring personal recovery in people with a psychotic disorder based on CHIME: A comparison of three validated measures. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2020, 29, 808–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keet, R.; Mahon, M.d.V.-M.; Shields-Zeeman, L.; Ruud, T.; van Weeghel, J.; Bahler, M.; Mulder, C.L.; van Zelst, C.; Murphy, B.; Westen, K.; et al. Recovery for all in the community; position paper on principles and key elements of community-based mental health care. BMC Psychiatry 2019, 19, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slade, M.; Leamy, M.; Bacon, F.; Janosik, M.; Le Boutillier, C.; Williams, J.; Bird, V. International differences in understanding recovery: Systematic review. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 2012, 21, 353–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Guarnido, A.J.; Ruiz-Granados, M.I.; Garrido-Cervera, J.A.; Herruzo, J.; Herruzo, C. Implementation of the Recovery Model and Its Outcomes in Patients with Severe Mental Disorder. Healthcare 2024, 12, 952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slade, M.; Longden, E. Empirical evidence about recovery and mental health. BMC Psychiatry 2015, 15, 285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, N.P.; Josephsson, S.; Alsaker, S. A narrative study of mental health recovery: Exploring unique, open-ended and collective processes. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Health Well-Being 2020, 15, 1747252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clift, S.; Camic, P.M. Oxford Textbook of Creative Arts, Health, and Well-Being: International Perspectives on Practice, Policy, and Research; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Crawford, P.; Lewis, L.; Brown, B.; Manning, N. Creative practice as mutual recovery in mental health. Ment. Health Rev. J. 2013, 18, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman-Casanova, J.M.; Guzman-Parra, J.; Mayoral-Cleries, F.; Cuesta-Lozano, D. Community-based art groups in mental health recovery: A systematic review and narrative synthesis. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2024, 31, 158–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tymoszuk, U.; Spiro, N.; Perkins, R.; Mason-Bertrand, A.; Gee, K.; Williamon, A. Arts engagement trends in the United Kingdom and their mental and social wellbeing implications: HEartS Survey. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0246078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bungay, H.; Vella-Burrows, T. The effects of participating in creative activities on the health and well-being of children and young people: A rapid review of the literature. Perspect. Public Health 2013, 133, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cases-Cunillera, J.; del Río Sáez, R.; Vila-Mumbrú, N.; Simó-Algado, S. Artistic Couples: Creative experiences for mental health (2006–2023). Arteterapia 2024, 19, e91702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cases-Cunillera, J.; Del Río Sáez, R.; Simó-Algado, S. Personal narratives from a mental health community art-based project: Insights from collaborative creation. Qual. Health Res. 2024; advance online publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W.; Plano Clark, V.L. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research, 3rd ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.; Burris, M.A. Photovoice: Concept, methodology, and use for participatory needs assessment. Health Educ. Behav. 1997, 24, 369–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson Clarke, L.M.; Warner, B. Exploring recovery perspectives in individuals diagnosed with mental illness. Occup. Ther. Ment. Health 2016, 32, 400–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Burris, M.A. Empowerment through photo novella: Portraits of participation. Health Educ. Q. 1994, 21, 171–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dulek, E.B.; Stein, C.H. The way I see it: Older adults with mental illness share their views of community life using Photovoice. Community Ment. Health J. 2024, 60, 457–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Golden, T. Reframing Photovoice: Building on the method to develop more equitable and responsive research practices. Qual. Health Res. 2020, 30, 960–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, C.; Oliffe, J. Photovoice in mental illness research: A review and recommendations. Health 2016, 20, 110–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charlton, J. Nothing About Us Without Us: Disability Oppression and Empowerment; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.C.; Morrel-Samuels, S.; Hutchison, P.M.; Bell, L.; Pestronk, R.M. Flint Photovoice: Community building among youths, adults, and policymakers. Am. J. Public Health 2004, 94, 911–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budig, K.; Diez, J.; Conde, P.; Sastre, M.; Hernán, M.; Franco, M. Photovoice and empowerment: Evaluating the transformative potential of a participatory action research project. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, H.; Neil, S.T.; Dunn, G.; Morrison, A.P. Psychometric properties of the questionnaire about the process of recovery (QPR). Schizophr. Res. 2014, 156, 184–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman-Casanova, J.M.; Cuesta-Lozano, D.; García-Gallardo, M.; Durán-Jiménez, F.J.; Mayoral-Cleries, F.; Guzmán-Parra, J. Measuring mental health recovery: Cross-cultural adaptation of the 15-item Questionnaire about the Process of Recovery in Spain (QPR-15-SP). Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2022, 31, 650–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hancock, N.; Scanlan, J.N.; Honey, A.; Bundy, A.C.; O’Shea, K. Recovery assessment scale–domains and stages (RAS-DS): Its feasibility and outcome measurement capacity. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 2015, 49, 624–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hancock, N.; The University of Sydney. Recovery Assessment Scale—Domains and Stages (RAS-DS)—Research Version 3. Spanish Translation by Daniela Fuentes O. & Sofía Astorga P. 2018. Available online: https://ras-ds.net.au/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/RAS-DS_2016_Spanish.pdf (accessed on 17 February 2025).

- The EuroQol Group. EuroQol—A new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life. Health Policy 1990, 16, 199–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herdman, M.; Badia, X.; Berra, S. The EuroQol-5D: A simple alternative for measuring health-related quality of life in primary care. Aten. Primaria 2001, 28, 425–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryff, C.D.; Keyes, C.L.M. The structure of psychological well-being revisited. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1995, 69, 719–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz, D.; Rodríguez-Carvajal, R.; Blanco, A.; Moreno-Jiménez, B.; Gallardo, I.; Valle, C.; van Dierendonck, D. Spanish adaptation of the Psychological Well-Being Scales (PWBS). Psicothema 2006, 18, 572–577. Available online: https://reunido.uniovi.es/index.php/PST/article/view/8474 (accessed on 10 February 2024). [PubMed]

- Boyd, J.E.; Adler, E.P.; Otilingam, P.G.; Peters, T. Internalized stigma of mental illness (ISMI) scale: A multinational review. Compr. Psychiatry 2014, 55, 221–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bengochea-Seco, R.; Arrieta-Rodríguez, M.; Fernández-Modamio, M.; Santacoloma-Cabero, I.; De Tojeiro-Roce, J.G.; García-Polavieja, B.; Santos-Zorrozúa, B.; Gil-Sanz, D. Adaptation into Spanish of the Internalised Stigma of Mental Illness scale to assess personal stigma. Rev. Psiquiatr. Salud Ment. 2018, 11, 244–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hergenrather, K.C.; Rhodes, S.D.; Cowan, C.A.; Bardhoshi, G.; Pula, S. PhotoVoice as community-based participatory research: A qualitative review. Am. J. Health Behav. 2009, 33, 686–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed.; American Psychiatric Publishing: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, S.; Gurung, D.; Kohrt, B. The PhotoVoice method for collaborating with people with lived experience of mental health conditions to strengthen mental health services. Camb. Prisms Glob. Ment. Health 2023, 10, e80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jay, E.; Patterson, C.F.; Fernandez, R.; Moxham, L. Experiences of recovery among adults with a mental illness using visual art methods: A systematic review. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2022, 30, 361–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vansteenkiste, T.; Morrens, M.; Westerhof, G.J. Images of recovery: A PhotoVoice study on visual narratives of personal recovery in persons with serious mental illness. Community Ment. Health J. 2021, 57, 1151–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorny-Wegrzyn, E.; Perry, B. Creative Art: Connection to Health and Well-Being. Open J. Soc. Sci. 2022, 10, 290–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boumans, J.; Oderwald, A.; Kroon, H. Self-perceived relations between artistic creativity and mental illness: A study into lived experiences. Front. Public Health 2024, 12, 1353757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamb, J. Creating change: Using the arts to help stop the stigma of mental illness and foster social integration. J. Holist. Nurs. 2009, 27, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaragoza Bernal, J.M. Mental health, subjective experiences and environmental change. Med. Humanit. 2024, 50, 417–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Donnell, S.; Lohan, M.; Oliffe, J.L.; Grant, D.; Galway, K. The acceptability, effectiveness and gender responsiveness of participatory arts interventions in promoting mental health and Wellbeing: A systematic review. Arts Health 2022, 14, 186–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dadswell, A.; Wilson, C.; Bungay, H.; Munn-Giddings, C. The role of participatory arts in addressing the loneliness and social isolation of older people: A conceptual review of the literature. J. Arts Communities 2017, 9, 109–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrido-Cervera, J.A.; Ruiz-Granados, M.I.; Cuesta-Vargas, A.I.; Sánchez-Guarnido, A.J. Patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) for recovery in mental health: A scoping review. Community Ment. Health J. 2024; advance online publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simó, S. Unveiling the Power of Art and Culture: Enhancing Mental Health and Social Engagement in the South Mediterranean with Insights from Catalonia; Euro-Mediterranean Economists Association (EMEA): Barcelona, Spain, 2024; Available online: https://euromed-economists.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/C4M-Power-Art-Culture-Report-2024_FV_compressed.pdf (accessed on 18 February 2025).

- Kim, S.-Y.; Kweon, Y.-R. The Poetry of Recovery in Peer Support Workers with Mental Illness: An Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis. Healthcare 2024, 12, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vigué, G.P.; Prieto, I.C.; Del Río Sáez, R.; Masana, R.V.; Algado, S.S. Training peer support workers in mental health care: A mixed methods study in Central Catalonia. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 791724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | ||

| 18–30 | 8 | 26.66 |

| 31–50 | 10 | 33.33 |

| 51–65 | 12 | 40 |

| Gender | ||

| Women | 15 | 50 |

| Men | 15 | 50 |

| Civil status | ||

| Single | 22 | 73.33 |

| Married | 3 | 10 |

| Divorced | 2 | 6.66 |

| Unspecified | 2 | 6.66 |

| Unmarried couple | 1 | 3.33 |

| Living with | ||

| My family | 18 | 60 |

| Alone | 7 | 23.33 |

| Supported household | 2 | 6.66 |

| In a group | 2 | 6.66 |

| With partner | 1 | 3.33 |

| Academic training | ||

| University degree | 7 | 23.33 |

| Secondary education | 6 | 20 |

| Primary education | 5 | 16.66 |

| Advanced education | 4 | 13.33 |

| High school | 4 | 13.33 |

| Without studies | 2 | 6.66 |

| Third-cycle university studies | 1 | 3.33 |

| Unclassified | 1 | 3.33 |

| Job situation | ||

| Transitory/permanent incapacity | 12 | 42.85 |

| Unspecified | 8 | 28.57 |

| Unemployed (with or without subsidy) | 4 | 14.28 |

| Active (working) | 3 | 10.71 |

| Retired | 1 | 3.57 |

| Mental health diagnoses categories (main) | ||

| Schizophrenia spectrum and other psychotic disorders | 14 | 46.67 |

| Bipolar and related disorders | 7 | 23.33 |

| Depressive disorders | 4 | 13.33 |

| Personality disorder | 4 | 13.33 |

| Disruptive, impulse control, and conduct disorders | 1 | 3.33 |

| Institution (Region) | ||

| Osonament (Osona) | 7 | 23.33 |

| Institut Pere Mata (Tarragonès) | 7 | 23.33 |

| El Far (Vallès Oriental) | 7 | 23.33 |

| La Muralla (Tarragonès) | 5 | 16.66 |

| Alterarte (Maresme) | 4 | 13.33 |

| Specific service | ||

| Community rehabilitation service | 16 | 53.33 |

| Social club | 14 | 46.66 |

| Artistic discipline used in the project | ||

| Visual arts | 25 | 83.33 |

| Literary arts | 3 | 10 |

| Music | 1 | 3.33 |

| Applied arts | 1 | 3.33 |

| Themes | Sub Themes | Quotes |

|---|---|---|

| Artmaking as an artistic couple | Creative and collaborative process | “The final work, the result, is very important because it is what is seen, the visual aspect. But I believe that the meaning, the process, is equally important”—Participant 23 |

| “It also helps me relax, enjoy the process, and it’s a moment we share—an hour and a half, two hours. And many times, we meet up and don’t even paint; we just go to have a chat”—Participant 1 | ||

| To express or to explain | “It wasn’t therapy for me, but a way to explain what happened to me or how I was inside. As a child, I didn’t express myself clearly, and they always said, ‘Get me a drawing’”—Participant 23 | |

| “For me, it’s about understanding myself and communicating what I do not understand about myself. I try to make sense of it and hope others can as well”—Participant 21 | ||

| “It helps me a lot to express, to externalize”—Participant 19 | ||

| Art through nature | “My process has been in a wonderful place, in the middle of nature. The calm and disconnection that I have had. For me, it has been a very beautiful and wonderful experience”—Participant 4 | |

| “Contact with nature is very healthy for me”—Participant 30 | ||

| Social connections | A conversation starts | “We talked a bit about what we liked to paint or what we liked to express. I was in a process when Artistic Couples started where I felt overwhelmed. I thought, if I’m going to dedicate so much time to a project, to a piece, working with someone where it doesn’t just depend on me, I want it to be personal. And, in fact, that’s how it was”—Participant 1 |

| To share with my artistic couple | “I think that when you have feeling and stick more you relax and end up talking about personal things. So, we talked about our things. They had nothing to do with ceramics. His life, my life, this happened to me, it happened to me the other…”—Participant 4 | |

| “So now I really enjoy being in contact with my artistic couple and seeing that she adapts to what I do, and that what she suggests to expand my work also appeals to me. I mean, it’s a very interesting and productive exchange”—Participant 2 | ||

| Solitude | “Being an artistic couple helps me get through unwanted loneliness”—Participant 6 | |

| “The power of feeling connected to others… helps me grow. It’s therapy for me”—Participant 8 | ||

| “I meet more people, expand my circle of friends, and experiment”—Participant 19 | ||

| Understanding mental health recovery | Overcoming my current situation | “I tried to paint, but nothing came out. I was struggling and felt like I wasn’t making any progress. It was overwhelming, and I decided I wanted to stop. I felt very anxious”—Participant 24 |

| “I wanted to approach Artistic Couples in connection with my personal process. Like, how do I feel right now? I feel a bit like ‘hear, see, and stay silent’, and I don’t want to feel that way”.—Participant 1 | ||

| “Don’t treat me this way” | “My artistic couple told me, I had prejudices about how you would be, and, you’re just a very normal person’. That whole idea of normality—like, you have your studies ‘Yes, yes, I do’, you have your family. So, just very normal. And cool, but I wasn’t expecting that”—Participant 3 | |

| Engaging in meaningful activities | “I need to occupy my mind”—Participant 21 | |

| “When I pick up a book, I escape reality and enter a new one”—Participant 1 |

| Measures | Mean | Median | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participants’ attendance sessions | 73.81% | 79.16% | 25.29% | |

| Photographs taken by each participant | 6.5 | 5 | 6.20 | |

| Satisfaction survey of each Photovoice session (52 answers) | ||||

| Quantitative part | Mean | Median | SD | Range (0 (low)–10 (high)) |

| 1. Degree of functioning of the activity | 9.48 | 10 | 0.80 | 0–10 |

| 2. Timetable and duration of the activity | 9.15 | 10 | 1.19 | 0–10 |

| 3. Overall level of satisfaction | 9.48 | 10 | 0.92 | 0–10 |

| Qualitative part | Overarching themes | Quotes | ||

| 4. Strengths | Social interaction and support; empathy and sharing emotions; and learning and discovery | “Being able to listen to the points of view of other participants and share opinions”, “The empathy among attendees”, “It ended up being a very pleasant and friendly group”, “I really enjoy it when we get together as a group and exchange impressions, discovering things and places…. That’s what I think happened today, and it’s something I truly enjoyed” | ||

| 5. Weaknesses | Dynamics and structure of the session; environmental comfort; and attendance and participation | “At the beginning of the activity, there were more people, and later there were fewer of us”, “We can almost never all be present”, “Going deeper”, “It felt short to me”, “Very hot in the classroom. A bit long in duration today” | ||

| 6. Improvement actions | Group duration and structure, and environmental comfort (physical conditions) | “Do it in different places”, “Go outside to the street”, “Take more external material”, “More interesting questions”, “That the session was not excessively long”. | ||

| Pre-Intervention | Post-Intervention | Test | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable (Range) | Mean | Median | SD a | Mean | Median | SD | T b | Z c | p-Value d |

| Mental health recovery | |||||||||

| QPR (15–60) | 37.53 | 38 | 16.1 | 36.29 | 37 | 12.34 | 0.54 | p = 0.593 | |

| RAS–DS (38–152) | 111.18 | 113 | 19.69 | 116.71 | 118 | 17.82 | 1.525 | p = 0.147 | |

| Doing things I value (6–24) | 19.35 | 20 | 3.48 | 20 | 21 | 3.58 | 0.79 | p = 0.425 | |

| Looking forward (18–72) | 50.35 | 51 | 11.83 | 52.06 | 50 | 8.79 | 0.84 | p = 0.413 | |

| Managing my illness (7–28) | 20.94 | 20 | 4.05 | 21.47 | 21 | 3.59 | 0.62 | p = 0.540 | |

| Connecting and belonging (7–28) | 20.53 | 21 | 3.22 | 21.94 | 22 | 3.21 | 2.51 | p = 0.023 | |

| Quality of life and psychological well-being | |||||||||

| EQ-5D (5–15) | 7.71 | 7 | 2.25 | 7.88 | 8 | 2.14 | 0.41 | p = 0.687 | |

| EQ-5D scale (0–100) | 56.47 | 65 | 28.31 | 60.59 | 60 | 20.30 | 0.90 | p = 0.379 | |

| PWB (39–234) | 142.53 | 143 | 35.1 | 142.88 | 145 | 33.16 | 0.08 | p = 0.935 | |

| Self–acceptance (6–36) | 19.53 | 16 | 7.68 | 18.35 | 16 | 6.55 | 0.96 | p = 0.334 | |

| Positive relations with others (6–36) | 21 | 22 | 6.72 | 22.65 | 23 | 7.85 | 1.13 | p = 0.276 | |

| Autonomy (8–48) | 29.29 | 30 | 8.86 | 29.35 | 30 | 7.7 | 0.060 | p = 0.953 | |

| Environmental mastery (6–36) | 20.65 | 20 | 7.32 | 20.53 | 19 | 6.31 | 0.12 | p = 0.907 | |

| Purpose in life (7–42) | 33 | 35 | 6.47 | 33.24 | 35 | 7.4 | 0.25 | p = 0.800 | |

| Personal growth (6–36) | 19.06 | 17 | 9.06 | 18.76 | 16 | 7.78 | 2.57 | p = 0.801 | |

| Self-stigma in mental health | |||||||||

| ISMI (29–116) | 58.94 | 56 | 12.68 | 58 | 59 | 12.79 | 0.87 | p = 0.395 | |

| Aligment (6–24) | 13.29 | 14 | 4.07 | 13.24 | 13 | 3.64 | 0.09 | p = 0.924 | |

| Assumption of stereotype or self-stigma (7–28) | 11.47 | 11 | 2.91 | 11.18 | 11 | 3.2 | 0.62 | p = 0.545 | |

| Perceived discrimiation or experience of discrimination (5–20) | 10.47 | 10 | 3.2 | 10.76 | 11 | 2.92 | 0.67 | p = 0.509 | |

| Social isolation (6–24) | 11.76 | 11 | 4.17 | 11.76 | 13 | 4.22 | 0.00 | p = 1.000 | |

| Resistance to stigma (5–20) | 11.94 | 11 | 3.47 | 11.06 | 11 | 2.9 | 1.06 | p = 0.304 | |

| Quantitative Part | Mean | Median | SD | Range (0 (Low)–10 (High)) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Degree of functioning of the activity | 8.9 | 9 | 1.53 | 0–10 |

| 2. Timetable and duration of the activity | 8.7 | 9 | 1.83 | 0–10 |

| 3. Overall level of satisfaction | 9 | 9 | 1.01 | 0–10 |

| Qualitative part | Overarching themes | Quotes | ||

| 4. Strengths | Social interaction and personal connection; emotional and therapeutic support; andlearning and personal development | “Share moments with a person”, “For a moment you feel free of everything that disturbs you”, “Exploring different ways of expression with art”, “To interact and gain new knowledge from other people” | ||

| 5. Weaknesses | Lack of time and organization;space and logistics limitations; and compatibility and communication issues | “I didn’t have the chance to see my partner as much as I would have liked”, “The displacement distance to the artist’s studio”, “We are two people with very different character and styles and sometimes we have not fully understood or connected” | ||

| 6. Improvement actions | Having more time; having a shared creative space; andorganizing more meetings between artists | “Having more time”, “Have a creative space to do the project”, “Diversify in different disciplines and touching them all to enrich you”, “I would love to keep painting more. I enjoy recreational activities; they relax me”. | ||

| Questions | Definitely Yes | Yes | No | Definitely No | Do Not Want to Answer |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Did the main researcher explain things in a way that was easy to understand? | 19 | 11 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Did the main researcher treat you with courtesy and respect? | 22 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Did you feel satisfied with the research process you experienced? | 21 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cases-Cunillera, J.; del Río Sáez, R.; Santos-López, J.M.; Simó-Algado, S. Mental Health Recovery Process Through Art: An Exploratory Mixed-Methods Multi-Center Study of an Art-Based Community Project. Healthcare 2025, 13, 1103. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13101103

Cases-Cunillera J, del Río Sáez R, Santos-López JM, Simó-Algado S. Mental Health Recovery Process Through Art: An Exploratory Mixed-Methods Multi-Center Study of an Art-Based Community Project. Healthcare. 2025; 13(10):1103. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13101103

Chicago/Turabian StyleCases-Cunillera, Jaume, Ruben del Río Sáez, Josep Manel Santos-López, and Salvador Simó-Algado. 2025. "Mental Health Recovery Process Through Art: An Exploratory Mixed-Methods Multi-Center Study of an Art-Based Community Project" Healthcare 13, no. 10: 1103. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13101103

APA StyleCases-Cunillera, J., del Río Sáez, R., Santos-López, J. M., & Simó-Algado, S. (2025). Mental Health Recovery Process Through Art: An Exploratory Mixed-Methods Multi-Center Study of an Art-Based Community Project. Healthcare, 13(10), 1103. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13101103