Exploring the Therapeutic Role of Coach-Guided Videoconferencing Expressive Writing in Multiple Sclerosis: A Qualitative Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design and Ethical Approval

2.2. Participants

2.3. Procedures

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

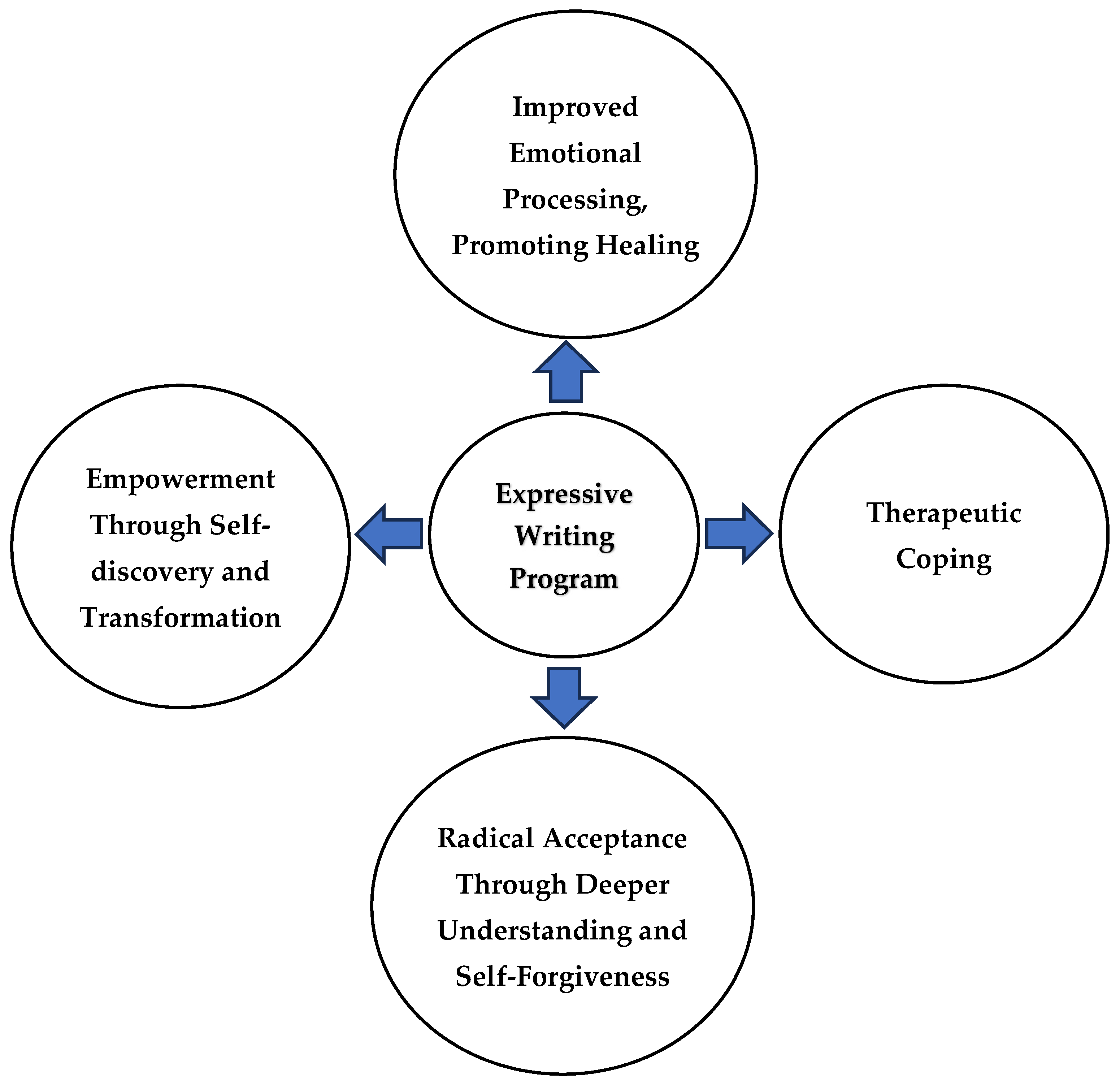

3.1. Theme 1: Improved Emotional Processing, Promoting Healing

3.1.1. Subtheme 1a: Brought Forth Deep, Allowed for Reflection

“It allowed me to kind of do a lot of self-introspection, and really kind of review my deeper feelings that I may not necessarily voice or really think about.”(P21)

“They were a few moments like that where it was just like boy, didn’t know that was still in there, I think I need to work on that.”(P13)

3.1.2. Subtheme 1b: Learning to Let Go

“Unstructured way of writing helped me to just kind of let go and I just felt like it kind of gave me permission to just do this for me.”(P3)

3.1.3. Subtheme 1c: Reclaiming Agency

“There was an empowering element to it. Where it allowed me to feel like I had a little bit more control over my uncontrollable situation.”(P12)

3.2. Theme 2: Therapeutic Coping

“I think that I am still making sense of what multiple sclerosis means to me and I’m grateful that this has helped define or allowed me to tap into different tools to wrap my mind around it a bit more and have a healthier relationship to it.”(P14)

“Writing helped to overcome my past failures, especially to deal with the issues that I was going through currently, and things that I’ve experienced in his past seven years of a diagnosis.”(P24)

3.3. Theme 3: Radical Acceptance Through Deeper Understanding and Self-Forgiveness

“I feel a lot more like grounded and defined in my acceptance of my disability in ways that maybe I wasn’t. I’m a little more gentle with myself. And I think I’m just like, in a little more even-keeled headspace than I was before the program started.”(P11)

“I’m more kind of willing to face how I’m feeling and thinking, whereas before, I would just, oh, well, you know, hey, I’ve already dealt with that. Let’s just move on, even though I haven’t. I’ve accepted my reality more. I’m more forgiving to myself.”(P18)

3.4. Theme 4: Empowerment Through Self-Discovery and Transformation

3.4.1. Subtheme 4a: Uncovered Hidden Creativity and Self-Expression

“I realized I’m able to tap into different creative sides. I didn’t really exist.”(P22)

3.4.2. Subtheme 4b: Offered a New Perspective on Life After Diagnosis

“It’s a completely different take on how I would’ve thought of MS. And the difficulties you know that occur with it.”(P5)

3.4.3. Subtheme 4c: Increased Optimism and Boosted Confidence

“I feel proud of myself and definitely boosted, yeah, emotionally and personally.”(P27)

“I think that it helped me become more positive. I’m, I’m more optimistic and hopeful now than I was, the writing helped. It was a very positive experience.”(P17)

4. Discussion

Strengths, Limitations, and Future Scope for Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Molinares, D.M.; Gater, D.R.; Daniel, S.; Pontee, N.L. Nontraumatic Spinal Cord Injury: Epidemiology, Etiology and Management. J. Pers. Med. 2022, 12, 1872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wallin, M.T.; Culpepper, W.J.; Campbell, J.D.; Nelson, L.M.; Langer-Gould, A.; Marrie, R.A.; Cutter, G.R.; Kaye, W.E.; Wagner, L.; Tremlett, H.; et al. The prevalence of MS in the United States: A population-based estimate using health claims data. Neurology 2019, 92, e1029–e1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pagalilauan, A.M.; Everest, E.; Rachimi, S.; Reich, D.S.; Waldman, A.D.; Sadovnick, A.D.; Vilarino-Guell, C.; Lenardo, M.J. The Canadian collaborative project on genetic susceptibility to multiple sclerosis cohort population structure and disease etiology. Front. Neurol. 2025, 16, 1509371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ridley, B.; Nonino, F.; Baldin, E.; Casetta, I.; Iuliano, G.; Filippini, G. Azathioprine for people with multiple sclerosis. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2024, 12, Cd015005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansson, S.; Ytterberg, C.; Claesson, I.M.; Lindberg, J.; Hillert, J.; Andersson, M.; Widén Holmqvist, L.; von Koch, L. High concurrent presence of disability in multiple sclerosis. Assoc. Perceived Health. J. Neurol. 2007, 254, 767–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larocca, N.G. Impact of walking impairment in multiple sclerosis: Perspectives of patients and care partners. Patient 2011, 4, 189–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, C.M. The lived experience of relapsing multiple sclerosis: A phenomenological study. J. Neurosci. Nurs. 1997, 29, 294–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santangelo, G.; Corte, M.D.; Sparaco, M.; Miele, G.; Garramone, F.; Cropano, M.; Esposito, S.; Lavorgna, L.; Gallo, A.; Tedeschi, G.; et al. Coping strategies in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis non-depressed patients and their associations with disease activity. Acta Neurol. Belg. 2021, 121, 465–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lex, H.; Price, P.; Clark, L. Qualitative study identifies life shifts and stress coping strategies in people with multiple sclerosis. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 6536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakash, R.S.; Schirda, B.; Valentine, T.R.; Crotty, M.; Nicholas, J.A. Emotion dysregulation in multiple sclerosis: Impact on symptoms of depression and anxiety. Mult. Scler. Relat. Disord. 2019, 36, 101399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pattison, S.J.; Mistretta, E.G.; Ehde, D.M.; Kratz, A.L.; Alschuler, K.N. Medical comorbidities in adults newly diagnosed with multiple sclerosis and clinically isolated syndrome: An observational study exploring prevalence, risk factors, and outcomes. Mult. Scler. Relat. Disord. 2025, 97, 106390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isaksson, A.K.; Gunnarsson, L.G.; Ahlström, G. The presence and meaning of chronic sorrow in patients with multiple sclerosis. J. Clin. Nurs. 2007, 16, 315–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luca, M.; Ortega-Castro, N.; Patti, F. Paediatric multiple sclerosis: A scoping review of patients’ and parents’ perspectives. Children 2022, 9, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahlström, G. Experiences of loss and chronic sorrow in persons with severe chronic illness. J. Clin. Nurs. 2007, 16, 76–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalb, R. The emotional and psychological impact of multiple sclerosis relapses. J. Neurol. Sci. 2007, 256 (Suppl. 1), S29–S33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, B.E.; Lakin, L.; Binns, C.C.; Currie, K.M.; Rensel, M.R. Patient and Provider Insights into the Impact of Multiple Sclerosis on Mental Health: A Narrative Review. Neurol. Ther. 2021, 10, 99–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gil-González, I.; Martín-Rodríguez, A.; Conrad, R.; Pérez-San-Gregorio, M. Quality of life in adults with multiple sclerosis: A systematic review. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e041249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, K.S. Emotional adjustment to a chronic illness. Lippincott’s Prim. Care Pract. 1998, 2, 38–51. [Google Scholar]

- Hainsworth, M.A. Living with multiple sclerosis: The experience of chronic sorrow. J. Neurosci. Nurs. 1994, 26, 237–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liedström, E.; Isaksson, A.K.; Ahlström, G. Chronic sorrow in next of kin of patients with multiple sclerosis. J. Neurosci. Nurs. 2008, 40, 304–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Reenen, E.C.; van Nistelrooij, I.A.M.; Visser, L.H.; de Beukelaar, J.W.K.; Frequin, S.; Niemeijer, A.R. The liminal space between hope and grief: The phenomenon of uncertainty as experienced by people living with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0315501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wills, O.; Manche, S.; Probst, Y. A Qualitative Exploration of the Socioecological Influences Shaping the Diagnostic Experience and Self-Management Practices Among People Newly Diagnosed With Multiple Sclerosis. Health Expect. 2024, 27, e70091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaksson, A.K.; Ahlström, G. Managing chronic sorrow: Experiences of patients with multiple sclerosis. J. Neurosci. Nurs. 2008, 40, 180–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russell, R.D.; Black, L.J.; Pham, N.M.; Begley, A. The effectiveness of emotional wellness programs on mental health outcomes for adults with multiple sclerosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Mult. Scler. Relat. Disord. 2020, 44, 102171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montañés-Masias, B.; Bort-Roig, J.; Pascual, J.C.; Soler, J.; Briones-Buixassa, L. Online psychological interventions to improve symptoms in multiple sclerosis: A systematic review: Online psychological interventions in Multiple Sclerosis. Acta Neurol. Scand. 2022, 146, 448–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lucien, A.; Francis, H.; Wu, W.; Woldhuis, T.; Gandy, M. The efficacy of cognitive behavioural therapy for depression and anxiety in multiple sclerosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Mult. Scler. Relat. Disord. 2024, 91, 105858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghielen, I.; Rutten, S.; Boeschoten, R.E.; Houniet-de Gier, M.; van Wegen, E.E.H.; van den Heuvel, O.A.; Cuijpers, P. The effects of cognitive behavioral and mindfulness-based therapies on psychological distress in patients with multiple sclerosis, Parkinson’s disease and Huntington’s disease: Two meta-analyses. J. Psychosom. Res. 2019, 122, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pouyanfard, S.; Mohammadpour, M.; ParviziFard, A.A.; Sadeghi, K. Effectiveness of mindfulness-integrated cognitive behavior therapy on anxiety, depression and hope in multiple sclerosis patients: A randomized clinical trial. Trends Psychiatry Psychother. 2020, 42, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gold, S.M.; Friede, T.; Meyer, B.; Moss-Morris, R.; Hudson, J.; Asseyer, S.; Bellmann-Strobl, J.; Leisdon, A.; Ißels, L.; Ritter, K.; et al. Internet-delivered cognitive behavioural therapy programme to reduce depressive symptoms in patients with multiple sclerosis: A multicentre, randomised, controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Digit. Health 2023, 5, e668–e678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolitzky-Taylor, K.; Fenwick, K.; Lengnick-Hall, R.; Grossman, J.; Bearman, S.K.; Arch, J.; Miranda, J.; Chung, B. A Preliminary Exploration of the Barriers to Delivering (and Receiving) Exposure-Based Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Anxiety Disorders in Adult Community Mental Health Settings. Community Ment. Health J. 2018, 54, 899–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennebaker, J.W. Putting stress into words: Health, linguistic, and therapeutic implications. Behav. Res. Ther. 1993, 31, 539–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, J.; Song, H.; Wang, Y.; Ren, Y.; Li, S.; Xiao, F.; Liao, S.; Xie, T.; Zhuang, W. Efficacy of expressive writing versus positive writing in different populations: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Nurs. Open 2023, 10, 5961–5974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, L. The delayed, durable effect of expressive writing on depression, anxiety and stress: A meta-analytic review of studies with long-term follow-ups. Br. J. Clin. Psychol. 2023, 62, 272–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smyth, J.M. Written emotional expression: Effect sizes, outcome types, and moderating variables. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1998, 66, 174–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pennebaker, J.W.; Beall, S.K. Confronting a traumatic event: Toward an understanding of inhibition and disease. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 1986, 95, 274–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennebaker, J.W.; Kiecolt-Glaser, J.K.; Glaser, R. Disclosure of Traumas and Immune Function: Health Implications for Psychotherapy. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1988, 56, 239–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nixon, R.D.V.; Kling, L.W. Treatment of adult post-traumatic stress disorder using a future-oriented writing therapy approach. Cogn. Behav. Ther. 2009, 2, 243–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bugg, A.; Turpin, G.; Mason, S.; Scholes, C. A randomised controlled trial of the effectiveness of writing as a self-help intervention for traumatic injury patients at risk of developing post-traumatic stress disorder. Behav. Res. Ther. 2009, 47, 6–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuen, H.K.; Kamp, E.V.; Green, S.; Edwards, L.; Kirklin, K.; Hanebrink, S.; Klebine, P.; Han, A.; Chen, Y. Effects of a coach-guided video-conferencing expressive writing program on facilitating grief resolution in adults with SCI. J. Spinal Cord Med. 2023, 1016–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemenover, S.H. The Good, the Bad, and the Healthy: Impacts of Emotional Disclosure of Trauma on Resilient Self-Concept and Psychological Distress. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2003, 29, 1236–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danoff-Burg, S.; Agee, J.D.; Romanoff, N.R.; Kremer, J.M.; Strosberg, J.M. Benefit finding and expressive writing in adults with lupus or rheumatoid arthritis. Psychol. Health 2006, 21, 651–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabbaghi, M.M.; Amini, L.; Nabavi, S.M.; Seyedfatemi, N.; Haghani, H. Effect of expressive writing on the sexual self-concept in men with multiple sclerosis: A randomized clinical controlled trial. BMC Neurol. 2025, 25, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afshar, B.; Amini, L.; Nabavi, S.M.; Hasani, M.; Mohammadnoori, M.; Jahanfar, S.; Sahebkar, A. What Effects Can Expressive Writing Have on Sexual Dysfunction in Women with Multiple Sclerosis? A Randomized Controlled Trial. Acta Neurol. Scand. 2023, 2023, 6754178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afshar, B.; Amini, L.; Nabavi, S.M.; Mohammadnouri, M.; Jahanfar, S.; Hasani, M. Effect of expressive writing on promotion of body image in women with multiple sclerosis: A randomized controlled trial. J. Maz. Univ. Med. Sci. 2021, 31, 54–67. [Google Scholar]

- Averill, A.J.; Kasarskis, E.J.; Segerstrom, S.C. Expressive disclosure to improve well-being in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: A randomised, controlled trial. Psychol. Health 2013, 28, 701–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cash, T.V.; Lageman, S.K. Randomized controlled expressive writing pilot in individuals with Parkinson’s disease and their caregivers. BMC Psychol. 2015, 3, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Can I use TA? Should I use TA? Should I not use TA? Comparing reflexive thematic analysis and other pattern-based qualitative analytic approaches. Couns. Psychother. Res. 2021, 21, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerger, H.; Werner, C.P.; Gaab, J.; Cuijpers, P. Comparative efficacy and acceptability of expressive writing treatments compared with psychotherapy, other writing treatments, and waiting list control for adult trauma survivors: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Psychol. Med. 2021, 52, 3484–3496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, C.T. Bracketing in qualitative research: Conceptual and practical matters. Psychother. Res. 2009, 19, 583–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greening, N. Phenomenological Research Methodology. Sci. Res. J. (SCIRJ) 2019, 7, 88–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gustavsen, S.; Olsson, A.; Søndergaard, H.B.; Andresen, S.R.; Sørensen, P.S.; Sellebjerg, F.; Oturai, A. The association of selected multiple sclerosis symptoms with disability and quality of life: A large Danish self-report survey. BMC Neurol. 2021, 21, 317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newland, P.K.; Naismith, R.T.; Ullione, M. The impact of pain and other symptoms on quality of life in women with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. J. Neurosci. Nurs. 2009, 41, 322–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vergo, M.T.; Klassen-Landis, M.; Li, Z.; Jiang, M.; Arnold, R.M. Getting Creative: Pilot Study of a Coached Writing Intervention in Patients with Advanced Cancer at a Rural Academic Medical Center. J. Palliat. Med. 2022, 25, 472–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corner, G.W.; Jhanwar, S.M.; Kelman, J.; Pessin, H.; Stein, E.; Breitbart, W. Visible ink: A flexible and individually tailored writing intervention for cancer patients. Palliat. Support. Care 2013, 13, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kartikaningsih, N.; Lawson, K.; Mayhan, M.; Spears, E.; Chew, O.; Green, S.; Tucker, S.C.; Kirklin, K.; Yuen, H.K. The Impact of an Expressive Writing and Storytelling Program on Ex-Offenders: A Pilot Study. Int. J. Offender Ther. Comp. Criminol. 2023, 306624x231188228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, E.; Shin, L.J.; Chen, L.; Lu, Q. Lived experiences of young adult Chinese American breast cancer survivors: A qualitative analysis of their strengths and challenges using expressive writing. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2023, 62, 102253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lumley, M.A.; Keefe, F.J.; Mosley-Williams, A.; Rice, J.R.; McKee, D.; Waters, S.J.; Partridge, R.T.; Carty, J.N.; Coltri, A.M.; Kalaj, A.; et al. The effects of written emotional disclosure and coping skills training in rheumatoid arthritis: A randomized clinical trial. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2014, 82, 644–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Xu, S.; Wen, X.; Liu, M. The effect of expressive writing on Chinese cancer patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized control trails. Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 2023, 30, 1357–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu-Odah, H.; Su, J.J.; Wang, M.; Sheffield, D.; Molassiotis, A. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the effectiveness of expressive writing disclosure on cancer and palliative care patients’ health-related outcomes. Support. Care Cancer 2023, 32, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hainsworth, M.A.; Burke, M.L.; Lindgren, C.L.; Eakes, G.G. Chronic sorrow in multiple sclerosis. A case study. Home Healthc. Nurse 1993, 11, 9–13. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hittle, M.; Culpepper, W.J.; Langer-Gould, A.; Marrie, R.A.; Cutter, G.R.; Kaye, W.E.; Wagner, L.; Topol, B.; Larocca, N.G.; Nelson, L.M.; et al. Population-Based Estimates for the Prevalence of Multiple Sclerosis in the United States by Race, Ethnicity, Age, Sex, and Geographic Region. JAMA Neurol. 2023, 80, 693–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finlayson, M.L.; Cho, C.C. A profile of support group use and need among middle-aged and older adults with multiple sclerosis. J. Gerontol. Soc. Work. 2011, 54, 475–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCabe, M.P.; Stokes, M.; McDonald, E. Changes in quality of life and coping among people with multiple sclerosis over a 2 year period. Psychol. Health Med. 2009, 14, 86–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, B.; Honomichl, R.; Sullivan, A.B. Effects of Conformity to Masculine Norms and Coping on Health Behaviors in Men with Multiple Sclerosis. Int. J. MS Care 2022, 24, 162–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraser, C.; Polito, S. A comparative study of self-efficacy in men and women with multiple sclerosis. J. Neurosci. Nurs. 2007, 39, 102–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| ID | Age (Years) | Gender | Race | Group or Solo Session | Marital Status | Education Level | Employment | Living Situation | Diagnosis | Duration of Diagnosis (Years) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 43 | F | B | G | M | PG | FT | WS | 1 | 16 |

| 2 | 47 | F | W | S | M | PG | FT | WS | 1 | 14 |

| 3 | 37 | F | W | G | M | PG | FT | WS | 1 | 6 |

| 5 | 65 | F | W | S | M | PG | H | WS | 2 | 5 |

| 6 | 38 | F | W | S | M | BA/BS | FT | WS | 1 | 25 |

| 7 | 56 | F | W | G | M | PG | H | WS | 3 | 4 |

| 8 | 59 | F | W | G | D | BA/BS | H | WS | 2 | 33 |

| 9 | 58 | M | W | G | M | PG | U | A | 1 | 9 |

| 10 | 36 | F | W | S | M | PG | H | WS | 1 | 8 |

| 11 | 39 | F | W | S | M | BA/BS | U | WS | 1 | 2 |

| 12 | 37 | F | W | G | M | BA/BS | H | WS | 1 | 5 |

| 13 | 49 | F | W | S | M | BA/BS | RT | WS | 1 | 1.5 |

| 14 | 39 | F | W | G | NM | BA/BS | FT | WS | 1 | 19 |

| 15 | 77 | M | O | G | W | PG | H | WS | 1 | 5 |

| 16 | 52 | F | W | S | M | PG | RT | WS | 1 | 25 |

| 17 | 60 | F | W | S | M | PG | U | WS | 1 | 11 |

| 18 | 78 | F | B | S | W | PG | U | WS | 1 | 11 |

| 19 | 55 | F | W | S | M | BA/BS | H | WS | 3 | 9 |

| 20 | 48 | M | W | S | D | BA/BS | U | A | 1 | 13 |

| 21 | 73 | M | W | S | M | PG | U | WS | 1 | 10 |

| 22 | 39 | F | B | S | M | SC | RT | WS | 3 | 10 |

| 23 | 42 | M | B | S | S | HS | U | WS | 3 | 7 |

| 24 | 60 | F | W | S | NM | SC | H | WS | 3 | 3 |

| 26 | 37 | F | B | S | NM | PG | PT | A | 2 | 30 |

| 27 | 35 | F | A | S | M | BA/BS | PT | WS | 1 | 17 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pawar, P.; Xie, S.M.; Varghese, A.R.; Smith, A.; Gao, J.; Kamp, E.V.; Kirklin, K.; Jones, B.A.; Meador, W.R.; Yuen, H.K. Exploring the Therapeutic Role of Coach-Guided Videoconferencing Expressive Writing in Multiple Sclerosis: A Qualitative Study. Healthcare 2025, 13, 1104. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13101104

Pawar P, Xie SM, Varghese AR, Smith A, Gao J, Kamp EV, Kirklin K, Jones BA, Meador WR, Yuen HK. Exploring the Therapeutic Role of Coach-Guided Videoconferencing Expressive Writing in Multiple Sclerosis: A Qualitative Study. Healthcare. 2025; 13(10):1104. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13101104

Chicago/Turabian StylePawar, Purva, Shelly M. Xie, Angel R. Varghese, Adrian Smith, Jie Gao, Elizabeth Vander Kamp, Kimberly Kirklin, Benjamin A. Jones, William R. Meador, and Hon K. Yuen. 2025. "Exploring the Therapeutic Role of Coach-Guided Videoconferencing Expressive Writing in Multiple Sclerosis: A Qualitative Study" Healthcare 13, no. 10: 1104. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13101104

APA StylePawar, P., Xie, S. M., Varghese, A. R., Smith, A., Gao, J., Kamp, E. V., Kirklin, K., Jones, B. A., Meador, W. R., & Yuen, H. K. (2025). Exploring the Therapeutic Role of Coach-Guided Videoconferencing Expressive Writing in Multiple Sclerosis: A Qualitative Study. Healthcare, 13(10), 1104. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13101104