Depressive Symptoms and Risk Factors During the COVID-19 Pandemic Among People with/Without Mental Disorders

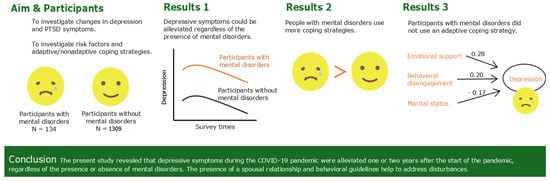

Abstract

1. Introduction

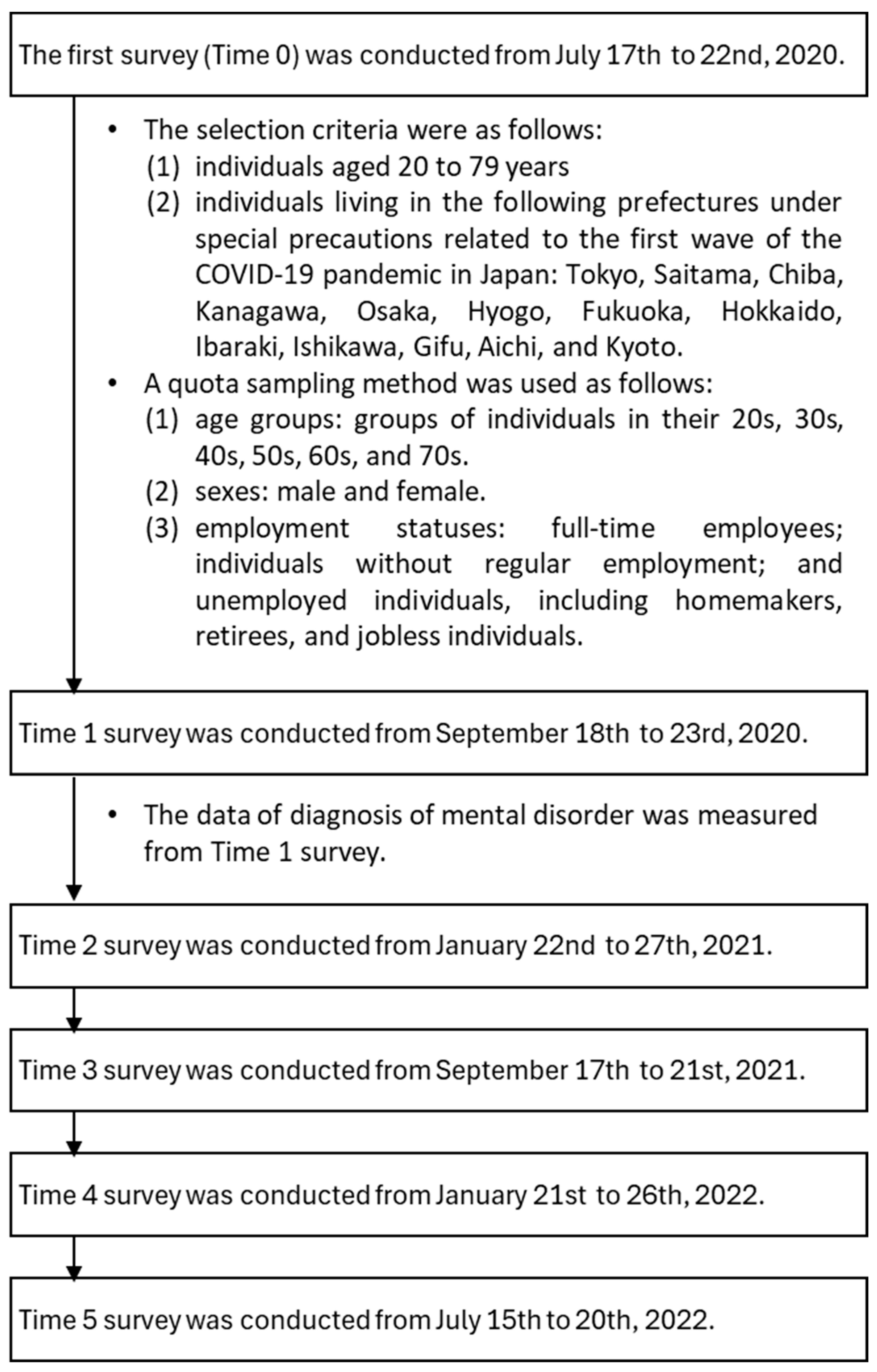

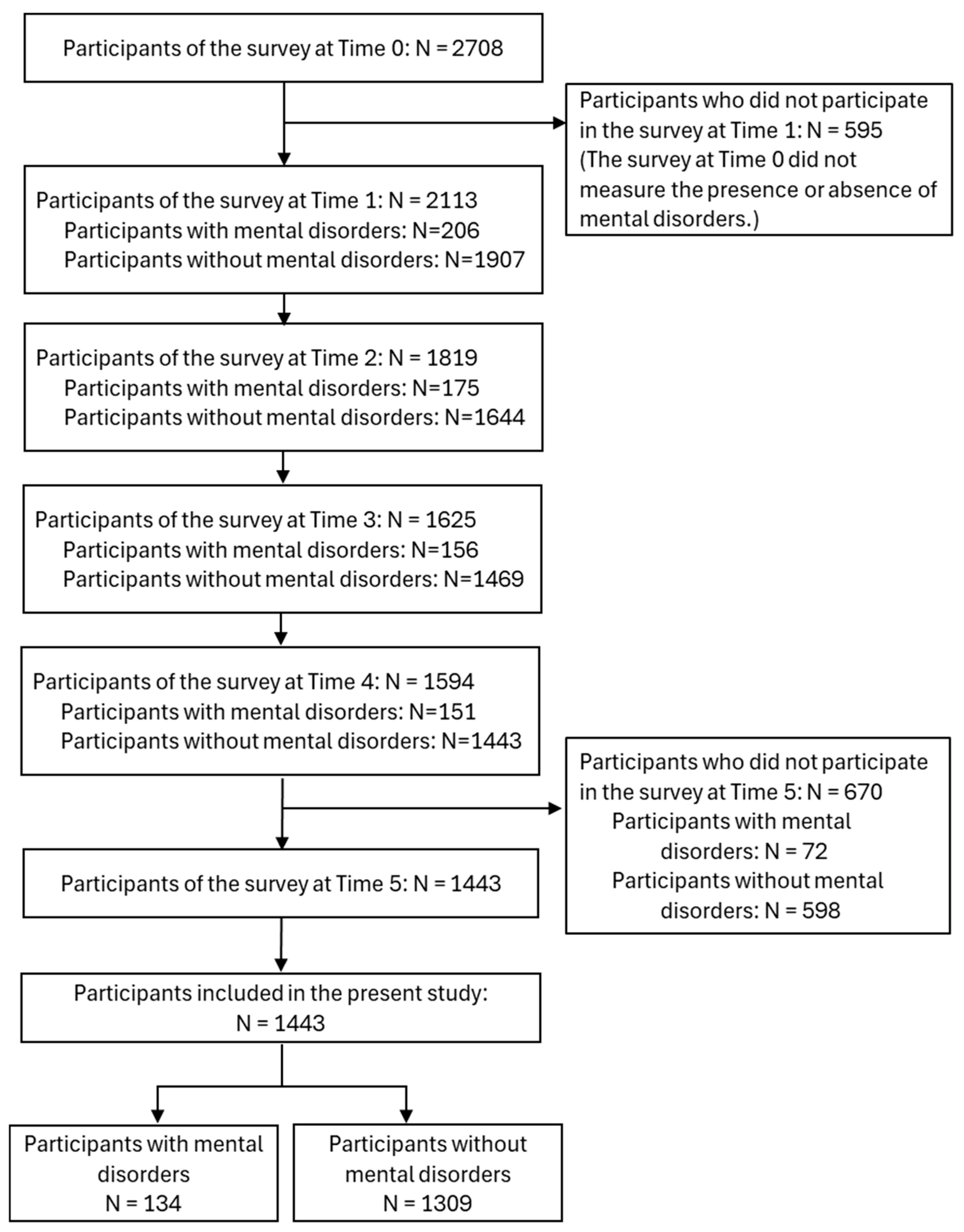

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Procedure

2.2. Measures

2.3. Sample Size

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the Participants

3.2. Changes in the PHQ-9 Score in Participants with and Without Mental Disorders

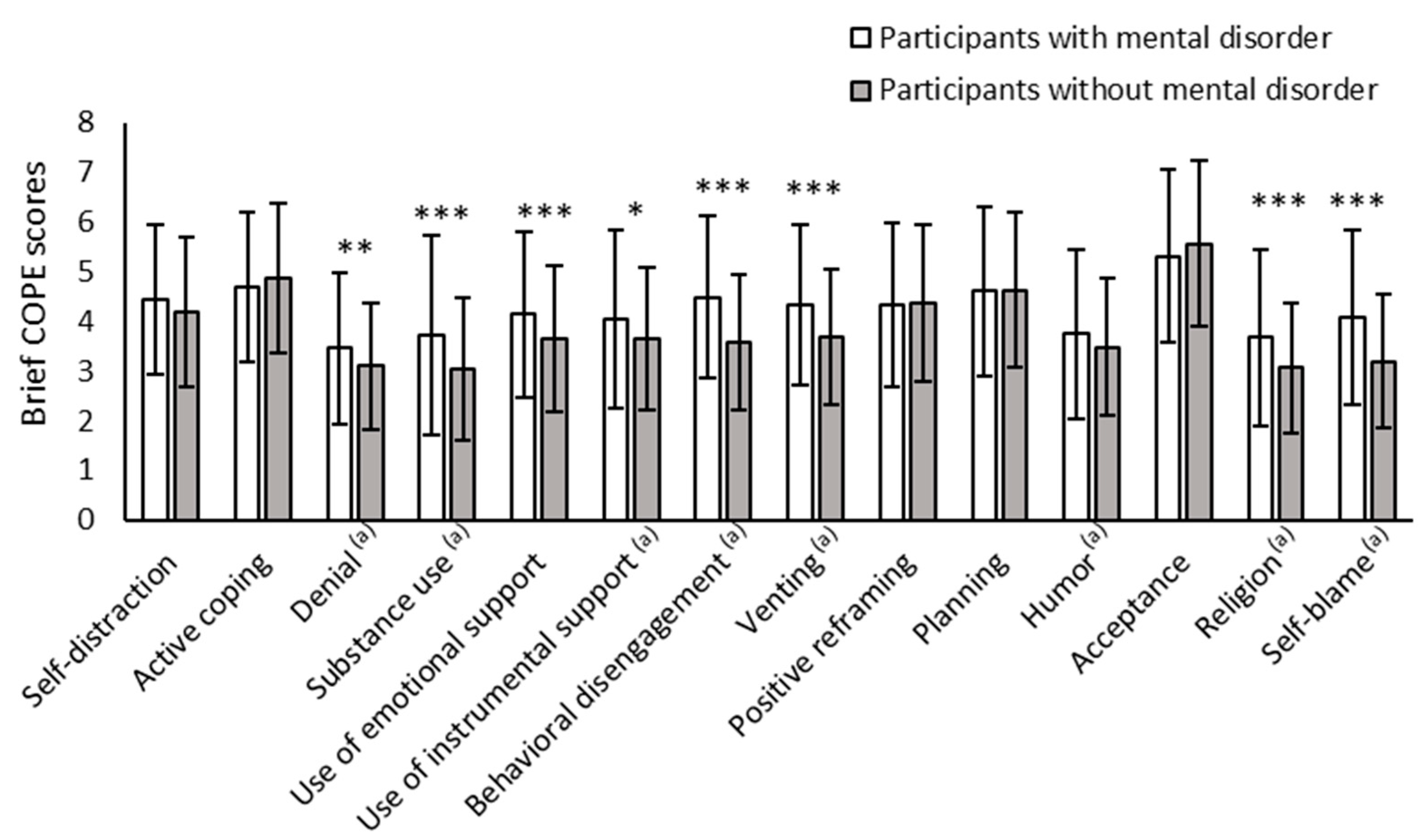

3.3. Frequency of Use of Coping Strategies Among Participants with and Without Mental Disorders

3.4. Risk Factors for Depressive Symptoms in and Coping Strategies of Participants with and Without Mental Disorders by PHQ-9 Score

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PHQ-9 | Patient Health Questionnaire-9 |

| Brief-COPE | Brief Coping Orientation to Problems Experienced |

| COVID-19 | Coronavirus disease 2019 |

| SARS-CoV-2 | Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 |

| SF-8 | Short-Form 8 |

| VIF | Variance Inflation Factor |

| PTSD | Posttraumatic stress disorder |

| ICD-10 | International statistical classification of diseases and related health problems 10th revision |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| SE | Standard Error |

References

- COVID-19 Mental Disorders Collaborators. Global prevalence and burden of depressive and anxiety disorders in 204 countries and territories in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet 2021, 398, 1700–1712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leung, C.M.C.; Ho, M.K.; Bharwani, A.A.; Cogo-Moreira, H.; Wang, Y.; Chow, M.S.C.; Fan, X.; Galea, S.; Leung, G.M.; Ni, M.Y. Mental disorders following COVID-19 and other epidemics: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Transl. Psychiatry 2022, 12, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pieh, C.; Budimir, S.; Delgadillo, J.; Barkham, M.; Fontaine, J.R.J.; Probst, T. Mental health during COVID-19 lockdown in the United Kingdom. Psychosom. Med. 2021, 83, 328–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chodkiewicz, J.; Miniszewska, J.; Krajewska, E.; Bilinski, P. Mental health during the second wave of the COVID-19 pandemic-polish studies. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Fazio, N.; Morena, D.; Delogu, G.; Volonnino, G.; Manetti, F.; Padovano, M.; Scopetti, M.; Frati, P.; Fineschi, V. Mental health consequences of COVID-19 pandemic period in the European population: An institutional challenge. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 9347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Favreau, M.; Hillert, A.; Osen, B.; Gartner, T.; Hunatschek, S.; Riese, M.; Hewera, K.; Voderholzer, U. Psychological consequences and differential impact of the COVID-19 pandemic in patients with mental disorders. Psychiatry Res. 2021, 302, 114045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Fernández, L.; Romero-Ferreiro, V.; Padilla, S.; López-Roldán, P.D.; Monzó-García, M.; Rodriguez-Jimenez, R. The impact on mental health patients of COVID-19 outbreak in Spain. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2021, 136, 127–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlegl, S.; Maier, J.; Meule, A.; Voderholzer, U. Eating disorders in times of the COVID-19 pandemic-results from an online survey of patients with anorexia nervosa. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2020, 53, 1791–1800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Rheenen, T.E.; Meyer, D.; Neill, E.; Phillipou, A.; Tan, E.J.; Toh, W.L.; Rossell, S.L. Mental health status of individuals with a mood-disorder during the COVID-19 pandemic in Australia: Initial results from the COLLATE project. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 275, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Fernández, L.; Romero-Ferreiro, V.; Rodriguez, V.; Alvarez-Mon, M.A.; Lahera, G.; Rodriguez-Jimenez, R. What about mental health after one year of COVID-19 pandemic? A comparison with the initial peak. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2022, 153, 104–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarus, R.S. Stress, Appraisal, and Coping; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Blanco, L.; Dal Santo, F.; Garcia-Alvarez, L.; De La Fuente-Tomas, L.; Lacasa, C.M.; Paniagua, G.; Saiz, P.A.; Garcia-Portilla, M.P.; Bobes, J. COVID-19 lockdown in people with severe mental disorders in Spain: Do they have a specific psychological reaction compared with other mental disorders and healthy controls? Schizophr. Res. 2020, 223, 192–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Troisi, A. Social stress and psychiatric disorders: Evolutionary reflections on debated questions. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2020, 116, 461–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, S.; Murphy, M.L.M.; Prather, A.A. Ten Surprising Facts About Stressful Life Events and Disease Risk. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2019, 70, 577–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saavedra, J.; Lopez, M.; Gonzalez, S.; Arias, S.; Crawford, P. Cognitive and Social Functioning Correlates of Employment Among People with Severe Mental Illness. Community Ment. Health J. 2016, 52, 851–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukase, Y.; Ichikura, K.; Murase, H.; Tagaya, H. Depression, risk factors, and coping strategies in the context of social dislocations resulting from the second wave of COVID-19 in Japan. BMC Psychiatry 2021, 21, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukase, Y.; Ichikura, K.; Murase, H.; Tagaya, H. Age-related differences in depressive symptoms and coping strategies during the COVID-19 pandemic in Japan: A longitudinal study. J. Psychosom. Res. 2022, 155, 110737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukase, Y.; Ichikura, K.; Tagaya, H. Symptoms and risk factors of depression and PTSD in the prolonged COVID-19 pandemic: A longitudinal survey conducted from 2020 to 2022 in Japan. BMC Psychiatry 2023, 23, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroenke, K.; Spitzer, R.L.; Williams, J.B. The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2001, 16, 606–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muramatsu, K.; Miyaoka, H.; Kamijima, K.; Muramatsu, Y.; Tanaka, Y.; Hosaka, M.; Miwa, Y.; Fuse, K.; Yoshimine, F.; Mashima, I.; et al. Performance of the Japanese version of the patient health questionnaire-9 (J-PHQ-9) for depression in primary care. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 2018, 52, 64–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carver, C.S. You want to measure coping but your protocol’s too long: Consider the brief COPE. Int. J. Behav. Med. 1997, 4, 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otsuka, Y.; Sasaki, T.; Iwasaki, K.; Mori, I. Working hours, coping skills, and psychological health in Japanese daytime workers. Ind. Health 2009, 47, 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peduzzi, P.; Concato, J.; Kemper, E.; Holford, T.R.; Feinstein, A.R. A simulation study of the number of events per variable in logistic regression analysis. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 1996, 49, 1373–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lakens, D.; Ravenzwaaij, D.V. Sample Size Justification. Collabra Psychol. 2022, 8, 33267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romanyukha, A.A.; Novikov, K.A.; Avilov, K.K.; Nestik, T.A.; Sannikova, T.E. The trade-off between COVID-19 and mental diseases burden during a lockdown: Mathematical modeling of control measures. Infect. Dis. Model. 2023, 8, 403–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, S.M.Y.; Chen, E.Y.H.; Suen, Y.N.; Wong, C.S.M.; Chang, W.C.; Chan, S.K.W.; McGorry, P.D.; Morgan, C.; van Os, J.; McDaid, D.; et al. Prevalence, time trends, and correlates of major depressive episode and other psychiatric conditions among young people amid major social unrest and COVID-19 in Hong Kong: A representative epidemiological study from 2019 to 2022. Lancet Reg. Health West. Pac. 2023, 40, 100881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabarrell-Pascuet, A.; Garcia-Mieres, H.; Gine-Vazquez, I.; Moneta, M.V.; Koyanagi, A.; Haro, J.M.; Domenech-Abella, J. The association of social support and loneliness with symptoms of depression, anxiety, and posttraumatic stress during the COVID-19 pandemic: A meta-analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 2765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moos, R.H.; Nichol, A.C.; Moos, B.S. Risk factors for symptom exacerbation among treated patients with substance use disorders. Addiction 2002, 97, 75–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, Z.; Wang, C.W.; Zhang, X.; Ho, A.H.; Wang, X.; Chan, C.L. Prevalence and determinants of depression among survivors 8 months after the Wenchuan earthquake. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2014, 202, 275–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, W.; Gao, L.; Fan, Y.; Wang, C.; Liu, Y.; Tian, F.; Yi, M.; Peng, X.; Liu, C. Identification of risk factors for attempted suicide by self-poisoning and a nomogram to predict self-poisoning suicide. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1106454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabir, R.; Bai, A.C.M.; Syed, H.Z.; Hasan, M.R.; Vinnakota, D.; Kar, S.K.; Singh, R.; Sathian, B.; Arafat, S.M.Y. The effect of COVID-19 on the mental health of the people in the Indian subcontinent: A scoping review. Nepal J. Epidemiol. 2023, 13, 1268–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.; Li, C.; Zhang, L.; Wang, T.; Cai, Z.; Lei, M. Evaluation of depression and its correlates in terms of demographics, eating habits, and exercises among university students: A multicenter cross-sectional analysis. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2024, 20, 1079–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katchamart, W.; Narongroeknawin, P.; Chanapai, W.; Thaweeratthakul, P.; Srisomnuek, A. Prevalence of and factors associated with depression and anxiety in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: A multicenter prospective cross-sectional study. Int. J. Rheum. Dis. 2020, 23, 302–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woo, J.; Whyne, E.Z.; Steinhardt, M.A. Psychological distress and self-reported mental disorders: The partially mediating role of coping strategies. Anxiety Stress Coping 2024, 37, 180–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, P.; Engdahl, B.; Gustavson, K.; Lund, I.O.; Pettersen, J.H.; Madsen, C.; Hauge, L.J.; Knudsen, A.K.S.; Reneflot, A.; Brandlistuen, R.E.; et al. Incidence rates of treated mental disorders before and during the COVID-19 pandemic-a nationwide study comparing trends in the period 2015 to 2021. BMC Psychiatry 2023, 23, 668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishikawa, H.; Tachimori, H.; Takeshima, T.; Umeda, M.; Miyamoto, K.; Shimoda, H.; Baba, T.; Kawakami, N. Prevalence, treatment, and the correlates of common mental disorders in the mid 2010′s in Japan: The results of the world mental health Japan 2nd survey. J. Affect. Disord. 2018, 241, 554–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Participants with Mental Disorders | Participants Without Mental Disorders | Statistics | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 134 | N = 1309 | ||||

| N/Mean | %/SD | N/Mean | %/SD | p | |

| Sex (N/%) | |||||

| Male | 90 | 67.2 | 715 | 54.6 | 0.005 |

| Female | 44 | 32.8 | 594 | 45.4 | |

| Age (Mean/SD) | 44.23 | 12.47 | 54.15 | 15.45 | <0.001 |

| Marital status (N/%) | |||||

| Single | 92 | 68.7 | 540 | 41.3 | <0.001 |

| Married | 42 | 31.3 | 769 | 58.7 | |

| Household income level (N/%) | |||||

| Less than 2 million JPY | 27 | 20.1 | 134 | 10.2 | <0.001 |

| Between 2 and 8 million JPY | 71 | 53.0 | 707 | 54.0 | |

| More than 8 million JPY | 7 | 5.2 | 222 | 17.0 | |

| Does not know or no answer | 29 | 21.6 | 246 | 18.8 | |

| Experienced an economic impact (N/%) | 59 | 44.0 | 458 | 35.0 | 0.038 |

| Diagnosis (N/%) (a) | |||||

| Depression | 62 | 46.3 | |||

| Stress-related and somatoform disorders | 20 | 14.9 | |||

| Bipolar disorder | 14 | 10.4 | |||

| Schizophrenia, schizotypal and delusional disorders | 16 | 11.9 | |||

| Neurotic disorders | 10 | 7.5 | |||

| Major neurocognitive disorder | 4 | 3.0 | |||

| Other disorders | 12 | 9.0 | |||

| Does not know disease name | 35 | 26.1 | |||

| Total | Participants with Mental Disorders | Participants Without Mental Disorders | p-Value | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | SE | Estimate | SE | Estimate | SE | Interaction | Survey Time | With/Without Mental Disorders | |

| Time 1 | 8.10 | 0.22 | 12.13 | 0.43 | 4.08 | 0.14 | 0.099 | 0.006 | <0.001 |

| Time 2 | 8.26 | 0.22 | 12.59 | 0.43 | 3.94 | 0.14 | |||

| Time 3 | 8.07 | 0.23 | 12.20 | 0.43 | 3.94 | 0.14 | |||

| Time 4 | 7.69 | 0.23 | 11.68 | 0.43 | 3.71 | 0.14 | |||

| Time 5 | 7.85 | 0.22 | 11.75 | 0.43 | 3.95 | 0.14 | |||

| Participants with Mental Disorders | Participants Without Mental Disorders | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | p | VIF | β | p | VIF | |

| PHQ-9 score at Time 1 | 0.55 | <0.001 | 1.35 | 0.62 | <0.001 | 1.29 |

| Sex | −0.04 | 0.571 | 1.14 | 0.01 | 0.450 | 1.39 |

| Age | 0.04 | 0.597 | 1.40 | −0.04 | 0.075 | 1.39 |

| Marital status | −0.17 | 0.049 | 1.44 | −0.01 | 0.709 | 1.66 |

| Household income level: Between 2 and 8 million JPY (Reference) | ||||||

| Less than 2 million JPY | 0.00 | 0.959 | 1.21 | 0.02 | 0.270 | 1.40 |

| More than 8 million JPY | 0.11 | 0.158 | 1.13 | 0.00 | 0.849 | 1.33 |

| No answer or does not know | 0.03 | 0.641 | 1.15 | −0.04 | 0.056 | 1.22 |

| Economic impact | −0.03 | 0.709 | 1.04 | 0.04 | 0.039 | 1.20 |

| Brief-COPE Inventory score at Time 5 | ||||||

| Self-distraction | −0.05 | 0.649 | 2.05 | 0.04 | 0.114 | 2.21 |

| Active coping | 0.02 | 0.852 | 2.56 | −0.10 | 0.001 | 2.72 |

| Denial | −0.14 | 0.155 | 2.16 | −0.02 | 0.486 | 2.06 |

| Substance use | 0.03 | 0.740 | 1.59 | 0.04 | 0.067 | 1.83 |

| Use of emotional support | 0.28 | 0.027 | 3.11 | −0.02 | 0.457 | 3.45 |

| Use of instrumental support | −0.05 | 0.656 | 2.74 | −0.01 | 0.766 | 3.12 |

| Behavioral disengagement | 0.20 | 0.025 | 1.93 | 0.11 | <0.001 | 1.82 |

| Venting | 0.01 | 0.959 | 2.13 | 0.04 | 0.131 | 3.50 |

| Positive reframing | −0.05 | 0.651 | 2.44 | 0.05 | 0.103 | 3.04 |

| Planning | −0.08 | 0.539 | 2.54 | −0.05 | 0.073 | 3.56 |

| Humor | 0.02 | 0.842 | 1.69 | −0.05 | 0.037 | 1.89 |

| Acceptance | −0.06 | 0.495 | 1.78 | 0.05 | 0.052 | 1.90 |

| Religion | 0.01 | 0.910 | 1.76 | 0.01 | 0.658 | 2.43 |

| Self-blaming | 0.11 | 0.291 | 2.38 | 0.10 | <0.001 | 2.25 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.40 | <0.001 | 0.55 | <0.001 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fukase, Y.; Ichikura, K.; Inaoka, H.; Tagaya, H. Depressive Symptoms and Risk Factors During the COVID-19 Pandemic Among People with/Without Mental Disorders. Healthcare 2025, 13, 1095. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13101095

Fukase Y, Ichikura K, Inaoka H, Tagaya H. Depressive Symptoms and Risk Factors During the COVID-19 Pandemic Among People with/Without Mental Disorders. Healthcare. 2025; 13(10):1095. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13101095

Chicago/Turabian StyleFukase, Yuko, Kanako Ichikura, Hidenori Inaoka, and Hirokuni Tagaya. 2025. "Depressive Symptoms and Risk Factors During the COVID-19 Pandemic Among People with/Without Mental Disorders" Healthcare 13, no. 10: 1095. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13101095

APA StyleFukase, Y., Ichikura, K., Inaoka, H., & Tagaya, H. (2025). Depressive Symptoms and Risk Factors During the COVID-19 Pandemic Among People with/Without Mental Disorders. Healthcare, 13(10), 1095. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13101095