The Mechanism by 18 RCTs Psychosocial Interventions Affect the Personality, Emotions, and Behaviours of Paediatric and Young Adult Cancer Patients: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

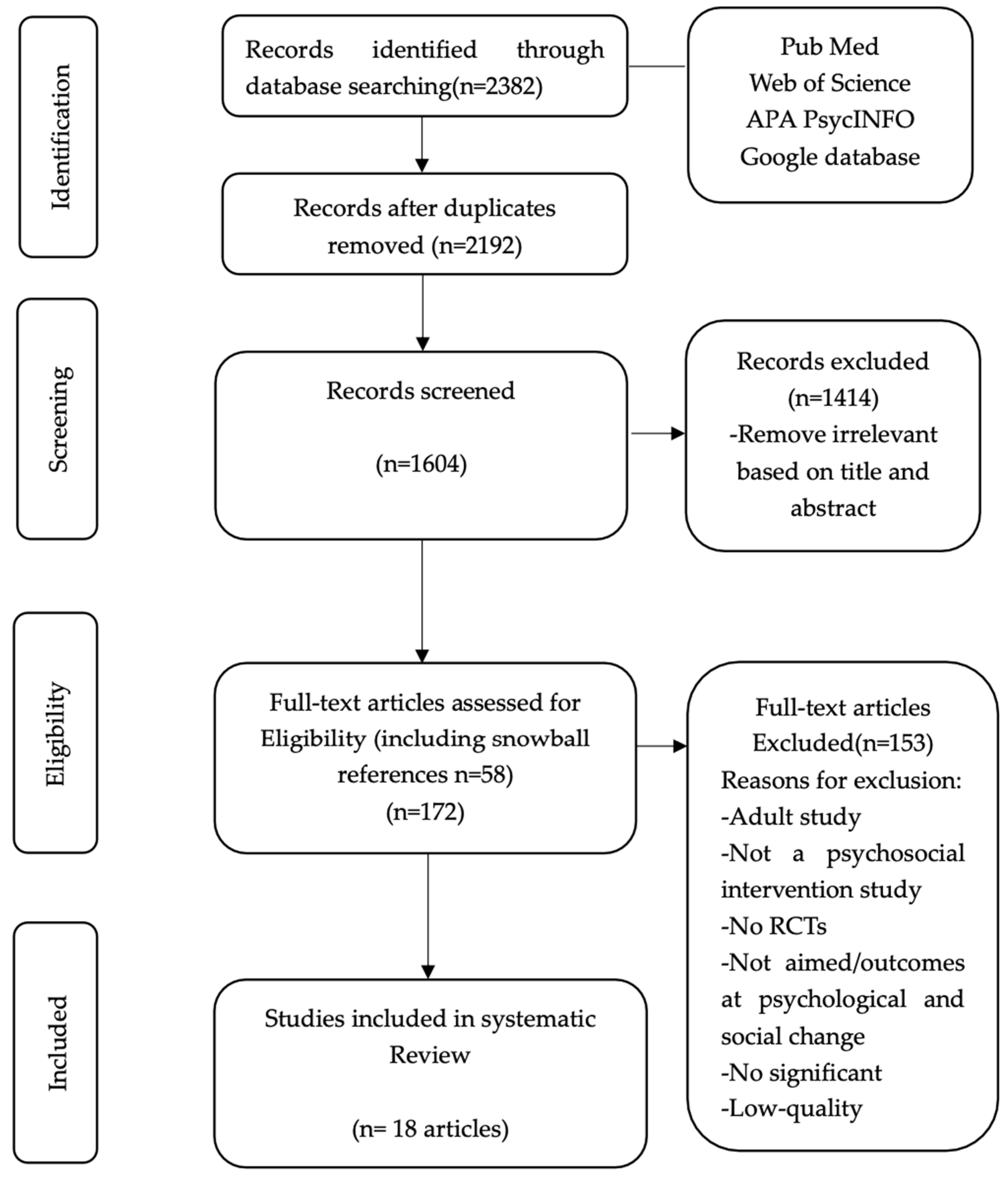

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Inclusion and Quality Assessment Process

2.3. Data Extraction and Analysis

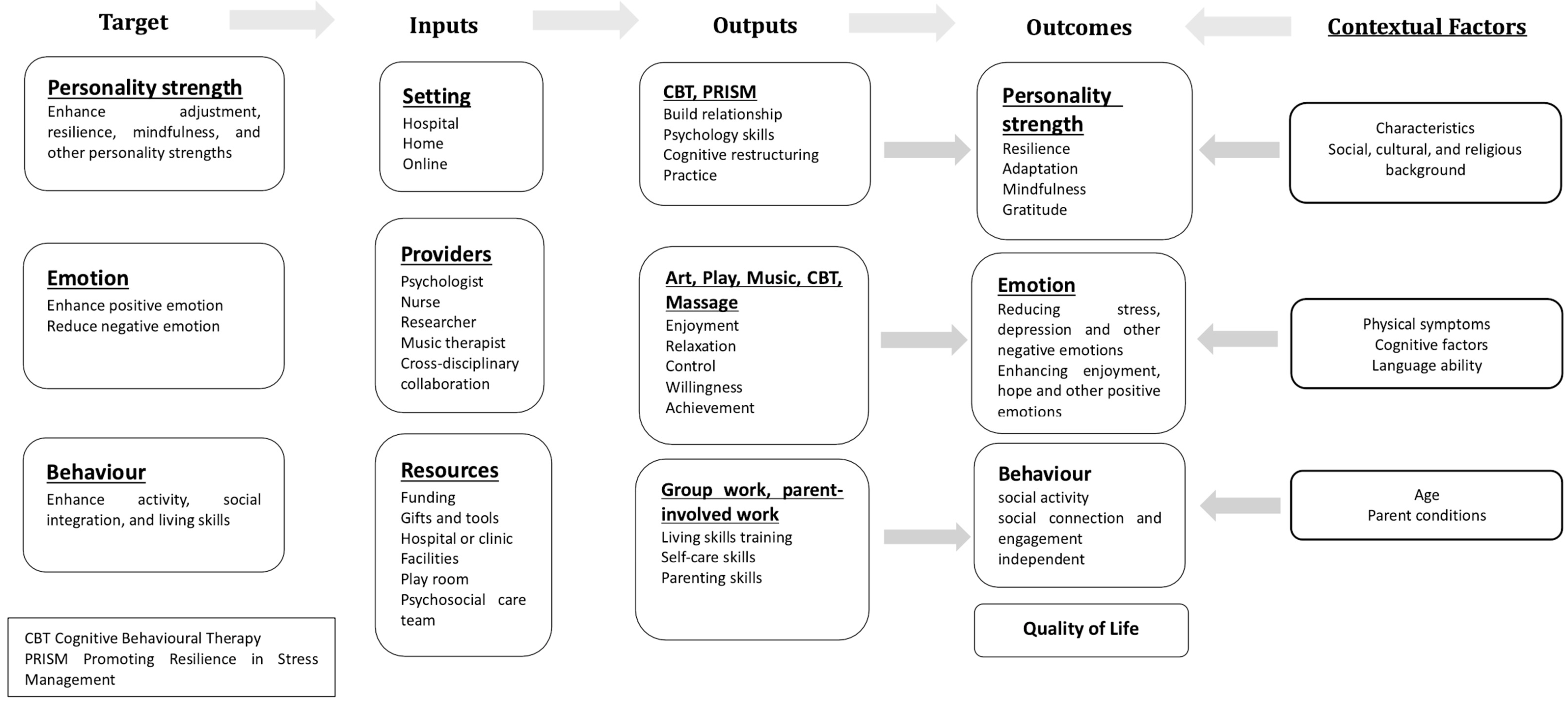

3. Results

3.1. General Features of Studies

3.2. Psychosocial Interventions, Objects, Measurement, and Outcomes

3.3. Therapeutic Interventions Leading to Personality Changes

3.3.1. Cognitive Reframing Influencing Personality Changes, Resilience and Adaption

3.3.2. Cognitive Reframing Also Brings Positive Changes in QoL and Emotion in the Long-Term

3.3.3. Resource Consuming in Therapeutic Interventions

3.4. Process-Oriented Activities Lead to Positive Emotional Changes

3.4.1. The Sense of Control and Initiative Can Affect Emotions

3.4.2. Play and Music Activities: Reducing Negativity and Enhancing Positivity Emotions

3.5. Interactive Interventions Lead to Behaviour Changes

3.5.1. Group Work Enhances Patients’ Social Integration

3.5.2. Parent-Involved Intervention Improves Patients’ Physical and Behavioural Abilities

3.6. Other Attributes to the Outcomes: Characteristics, Family and Social Environment

4. Discussion

4.1. The Value of Psychosocial Interventions for Patients

4.2. Progressive Psychosocial Interventions’ Development

4.3. Logic Model Enhances the Review

4.4. Limitations of Interventions and This Review

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Adamson, P.; Arons, D.; Baumberger, J.; Fluery, M.; Hoffman, R.; Leach, D.; Weiner, S. Translating Discovery into Cures for Children with Cancer-Childhood Cancer Research Landscape Report; Alliance for Childhood Cancer and the American Cancer Society: Alexandria, VA, USA, 2016; Available online: https://www.fightcancer.org/policy-resources/childhood-cancer-research-landscape-report (accessed on 20 July 2024).

- Baytan, B.; Aşut, Ç.; Çırpan Kantarcıoğlu, A.; Sezgin Evim, M.; Güneş, A.M. Health-Related Quality of Life, Depression, Anxiety, and Self-Image in Acute Lymphocytic Leukemia Survivors. Turk. J. Hematol. 2016, 33, 326–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grasaas, E.; Skarstein, S.; Mikkelsen, H.T.; Småstuen, M.C.; Rohde, G.; Helseth, S.; Haraldstad, K. The relationship between stress and health-related quality of life and the mediating role of self-efficacy in Norwegian adolescents: A cross-sectional study. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2022, 20, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jankowska-Polańska, B.; Sliwiński, M.; Świątoniowska, N.; Butrym, A.; Mazur, G. Quality of life in children with acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Scand. Caring Sci. 2020, 34, 380–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.C.W.; Lopez, V.; Joyce Chung, O.K.; Ho, K.Y.; Chiu, S.Y. The impact of cancer on the physical, psychological and social well-being of childhood cancer survivors. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2013, 17, 214–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeltzer, L.K.; Recklitis, C.; Buchbinder, D.; Zebrack, B.; Casillas, J.; Tsao, J.C.I.; Lu, Q.; Krull, K. Psychological Status in Childhood Cancer Survivors: A Report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2009, 27, 2396–2404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bessell, A.; Moss, T.P. Evaluating the effectiveness of psychosocial interventions for individuals with visible differences: A systematic review of the empirical literature. Body Image 2007, 4, 227–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joffe, M.; Mindell, J. Complex Causal Process Diagrams for Analyzing the Health Impacts of Policy Interventions. Am. J. Public Health 2006, 96, 473–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, M.; Choi, E.K.; Lyu, C.J.; Han, J.W.; Hahn, S.M. Family resilience factors affecting family adaptation of children with cancer: A cross-sectional study. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2022, 56, 102078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toledano-Toledano, F.; Luna, D.; Moral De La Rubia, J.; Martínez Valverde, S.; Bermúdez Morón, C.A.; Salazar García, M.; Vasquez Pauca, M.J. Psychosocial Factors Predicting Resilience in Family Caregivers of Children with Cancer: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wayant, C.; Manquen, J.; Wendelbo, H.; Kerr, N.; Crow, M.; Goodell, J.; Tricco, A.C.; Mack, J.W.; Hellman, C.; Vassar, M. Identification of Evidence for Key Positive Psychological Constructs in Pediatric and Adolescent/Young Adult Patients with Cancer: A Scoping Review. J. Adolesc. Young Adult Oncol. 2021, 10, 247–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zale, E.L.; Pierre-Louis, C.; Macklin, E.A.; Riklin, E.; Vranceanu, A.-M. The impact of a mind–body program on multiple dimensions of resiliency among geographically diverse patients with neurofibromatosis. J. Neurooncol. 2018, 137, 321–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoni, M.H. Psychosocial intervention effects on adaptation, disease course and biobehavioral processes in cancer. Brain Behav. Immun. 2013, 30, S88–S98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wechsler, A.M.; Sánchez-Iglesias, I. Psychological adjustment of children with cancer as compared with healthy children: A meta-analysis: Cancer adjustment meta-analysis. Eur. J. Cancer Care 2013, 22, 314–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaves, C.; Vázquez, C.; Hervás, G. Positive interventions in seriously-ill children: Effects on well-being after granting a wish. J. Health Psychol. 2016, 21, 1870–1883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumpulainen, K.; Lipponen, L.; Hilppö, J.; Mikkola, A. Building on the positive in children’s lives: A co-participatory study on the social construction of children’s sense of agency. Early Child Dev. Care 2014, 184, 211–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tugade, M.M.; Fredrickson, B.L. Resilient Individuals Use Positive Emotions to Bounce Back From Negative Emotional Experiences. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2004, 86, 320–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Mo, L.; Tang, Y.; Huang, X.; Tan, J. Effects of nursing intervention models on social adaption capability development in preschool children with malignant tumors: A randomized control trial. Psycho-Oncol. 2014, 23, 708–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arpaci, T.; Altay, N. Psychosocial interventions for childhood cancer survivors: Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized control trials. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2024, 69, 102541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torgerson, C.J.; Torgerson, D.J.; Director, Y.T.U. Randomised Trials in Education: An Introductory Handbook; Education Endowment Foundation: London, UK, 2013; Available online: https://durham-repository.worktribe.com/output/1607980/randomised-controlled-trials-in-education-an-introductory-handbook (accessed on 2 May 2025).

- Sterne, J.A.C.; Savović, J.; Page, M.J.; Elbers, R.G.; Blencowe, N.S.; Boutron, I.; Cates, C.J.; Cheng, H.-Y.; Corbett, M.S.; Eldridge, S.M.; et al. RoB 2: A revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2019, 366, l4898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Yao, D.; Ung, C.O.L.; Hu, H. Promoting Community Pharmacy Practice for Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) Management: A Systematic Review and Logic Model. Int. J. Chron. Obstruct. Pulmon. Dis. 2020, 15, 1863–1875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaveh, M.H.; Motamed-Jahromi, M.; Hassanipour, S. The Effectiveness of Interventions in Improving Hand Hygiene Compliance: A Meta-Analysis and Logic Model. Can. J. Infect. Dis. Med. Microbiol. 2021, 2021, 8860705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, G.; Zheng, J.; Tang, P.K.; Zheng, Y.; Hu, H.; Ung, C.O.L. Effectiveness of Hospital Pharmacist Interventions for COPD Patients: A Systematic Literature Review and Logic Model. Int. J. Chron. Obstruct. Pulmon. Dis. 2022, 17, 2757–2788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, G.; Chau, C.I.; Hu, H.; Ung, C.O.L. Pharmacist intervention for pediatric asthma: A systematic literature review and logic model. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2023, 19, 1487–1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motamed-Jahromi, M.; Kaveh, M.H. Effective Interventions on Improving Elderly’s Independence in Activity of Daily Living: A Systematic Review and Logic Model. Front. Public Health 2021, 8, 516151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winsper, C.; Crawford-Docherty, A.; Weich, S.; Fenton, S.-J.; Singh, S.P. How do recovery-oriented interventions contribute to personal mental health recovery? A systematic review and logic model. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2020, 76, 101815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, L.M.; Petticrew, M.; Rehfuess, E.; Armstrong, R.; Ueffing, E.; Baker, P.; Francis, D.; Tugwell, P. Using logic models to capture complexity in systematic reviews: Logic Models in Systematic Reviews. Res. Syn. Meth. 2011, 2, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coughtrey, A.; Millington, A.; Bennett, S.; Christie, D.; Hough, R.; Su, M.T.; Constantinou, M.P.; Shafran, R. The Effectiveness of Psychosocial Interventions for Psychological Outcomes in Pediatric Oncology: A Systematic Review. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2018, 55, 1004–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melesse, T.G.; Chau, J.P.C.; Nan, M. Effects of cognitive-behavioural therapy on psychological, physical and social outcomes of children with cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Psychosom. Res. 2022, 157, 110805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lench, H.; Darbor, K.; Berg, L. Functional Perspectives on Emotion, Behavior, and Cognition. Behav. Sci. 2013, 3, 536–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baxter, S.K.; Blank, L.; Woods, H.B.; Payne, N.; Rimmer, M.; Goyder, E. Using logic model methods in systematic review synthesis: Describing complex pathways in referral management interventions. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2014, 14, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kneale, D.; Thomas, J.; Harris, K. Developing and Optimising the Use of Logic Models in Systematic Reviews: Exploring Practice and Good Practice in the Use of Programme Theory in Reviews. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0142187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Subirana, M.; Long, A.; Greenhalgh, J.; Firth, J. A realist logic model of the links between nurse staffing and the outcomes of nursing. J. Res. Nurs. 2014, 19, 8–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haase, J.E.; Robb, S.L.; Burns, D.S.; Stegenga, K.; Cherven, B.; Hendricks-Ferguson, V.; Roll, L.; Docherty, S.L.; Phillips, C. Adolescent/Young Adult Perspectives of a Therapeutic Music Video Intervention to Improve Resilience During Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplant for Cancer. J. Music Ther. 2020, 57, 3–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenberg, A.R.; Zhou, C.; Bradford, M.C.; Salsman, J.M.; Sexton, K.; O’Daffer, A.; Yi-Frazier, J.P. Assessment of the Promoting Resilience in Stress Management Intervention for Adolescent and Young Adult Survivors of Cancer at 2 Years: Secondary Analysis of a Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e2136039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phipps, S.; Peasant, C.; Barrera, M.; Alderfer, M.A.; Huang, Q.; Vannatta, K. Resilience in Children Undergoing Stem Cell Transplantation: Results of a Complementary Intervention Trial. Pediatrics 2012, 129, e762–e770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemper, K.J.; Hamilton, C.A.; McLean, T.W.; Lovato, J. Impact of Music on Pediatric Oncology Outpatients. Pediatr. Res. 2008, 64, 105–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lester, E.G.; Macklin, E.A.; Plotkin, S.; Vranceanu, A.-M. Improvement in resiliency factors among adolescents with neurofibromatosis who participate in a virtual mind–body group program. J. Neurooncol. 2020, 147, 451–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robb, S.L.; Burns, D.S.; Stegenga, K.A.; Haut, P.R.; Monahan, P.O.; Meza, J.; Stump, T.E.; Cherven, B.O.; Docherty, S.L.; Hendricks-Ferguson, V.L.; et al. Randomized clinical trial of therapeutic music video intervention for resilience outcomes in adolescents/young adults undergoing hematopoietic stem cell transplant: A report from the Children’s Oncology Group. Cancer 2014, 120, 909–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robb, S.L.; Haase, J.E.; Perkins, S.M.; Haut, P.R.; Henley, A.K.; Knafl, K.A.; Tong, Y. Pilot Randomized Trial of Active Music Engagement Intervention Parent Delivery for Young Children with Cancer. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2017, 42, 208–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyon, M.E.; Jacobs, S.; Briggs, L.; Cheng, Y.I.; Wang, J. A Longitudinal, Randomized, Controlled Trial of Advance Care Planning for Teens With Cancer: Anxiety, Depression, Quality of Life, Advance Directives, Spirituality. J. Adolesc. Health 2014, 54, 710–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phipps, S.; Barrera, M.; Vannatta, K.; Xiong, X.; Doyle, J.J.; Alderfer, M.A. Complementary therapies for children undergoing stem cell transplantation: Report of a multisite trial. Cancer 2010, 116, 3924–3933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenberg, A.; Bradford, M.; Klein, V.; Etsekson, N.; Wharton, C.; Shaffer, M.; Yi-Frazier, J. The “Promoting Resilience in Stress Management” (PRISM) Intervention for Adolescents and Young Adults: A Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial (TH320A). J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2018, 55, 569–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, A.R.; Postier, A.; Osenga, K.; Kreicbergs, U.; Neville, B.; Dussel, V.; Wolfe, J. Long-Term Psychosocial Outcomes Among Bereaved Siblings of Children With Cancer. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2015, 49, 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Mo, L.; Torres, J.; Huang, X. Effects of cognitive behavioral therapy on psychological adjustment in Chinese pediatric cancer patients receiving chemotherapy: A randomized trial. Medicine 2019, 98, e16319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, R.; Shen, X.; Zhang, L.; Chan, Y.; Yao, W.; Zhang, G.; Li, H. Effects of Child Life intervention on the symptom cluster of pain–anxiety–fatigue–sleep disturbance in children with acute leukemia undergoing chemotherapy. Asia-Pac. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2023, 10, 100243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, A.; Mehraban, A.H.; Damavandi, S.A.; Zarei, M.A.; Haghani, H. The effect of play-based occupational therapy on symptoms and participation in daily life activities in children with cancer: A randomized controlled trial. Br. J. Occup. Ther. 2021, 84, 400–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamedi, V.; Hamid, N.; Beshlideh, K.; Marashi, S.A.; Hashemi Sheikh Shabani, S.E. Effectiveness of Conventional Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy and Its Computerized Version on Reduction in Pain Intensity, Depression, Anger, and Anxiety in Children with Cancer: A Randomized, Controlled Trial. Iran J. Psychiatry Behav. Sci. 2020, 14, e83110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulah, D.M.; Abdulla, B.M.O. Effectiveness of group art therapy on quality of life in paediatric patients with cancer: A randomized controlled trial. Complement. Ther. Med. 2018, 41, 180–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piasai, K.; Phumdoung, S.; Wiroonpanich, W.; Chotsampancharoen, T. A Randomized Control Trial of Guided-Imagination and Drawing-Storytelling in Children with Cancer. Pac. Rim Int. J. Nurs. Res. 2018, 22, 386–400. [Google Scholar]

- Shoshani, A.; Mifano, K.; Czamanski-Cohen, J. The effects of the Make a Wish intervention on psychiatric symptoms and health-related quality of life of children with cancer: A randomised controlled trial. Qual Life Res 2016, 25, 1209–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, A.R.; Bradford, M.C.; Junkins, C.C.; Taylor, M.; Zhou, C.; Sherr, N.; Kross, E.; Curtis, J.R.; Yi-Frazier, J.P. Effect of the Promoting Resilience in Stress Management Intervention for Parents of Children With Cancer (PRISM-P): A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Netw. Open 2019, 2, e1911578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alavi, B.; Makvandi, B.; Asgari, P.; Moradimanesh, F. Effectiveness of individual play therapy on hope, adjustment and pain response of children with leukemia hospitalized in Shahrivar Hospital, Rasht, Iran. Prev. Care Nurs. Midwifery J. 2021, 11, 10–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, J.B.; Domingos, J.; Almeida, A.S.; Castro, C.; Simões, A.; Fernandes, S.; Vareta, D.; Bernardes, C.; Fonseca, J.; Vaz, C.; et al. Enablers, barriers and strategies to build resilience among cancer survivors: A qualitative study protocol. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1049403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Terrill, A.L.; Molton, I.R.; Ehde, D.M.; Amtmann, D.; Bombardier, C.H.; Smith, A.E.; Jensen, M.P. Resilience, age, and perceived symptoms in persons with long-term physical disabilities. J. Health Psychol. 2016, 21, 640–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alderfer, M.A.; Long, K.A.; Lown, E.A.; Marsland, A.L.; Ostrowski, N.L.; Hock, J.M.; Ewing, L.J. Psychosocial adjustment of siblings of children with cancer: A systematic review. Psycho-Oncol. 2010, 19, 789–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ljungman, L.; Cernvall, M.; Grönqvist, H.; Ljótsson, B.; Ljungman, G.; Von Essen, L. Long-Term Positive and Negative Psychological Late Effects for Parents of Childhood Cancer Survivors: A Systematic Review. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e103340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, M.L.; Cavanaugh, C.E.; MacLeamy, J.B.; Sojourner-Nelson, A.; Koopman, C. Posttraumatic growth and adverse long-term effects of parental cancer in children. Fam. Syst. Health 2009, 27, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, R.M.; Chambers, D.A.; Glasgow, R.E. Big Data and Large Sample Size: A Cautionary Note on the Potential for Bias. Clin. Transl. Sci. 2014, 7, 342–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Publication | Country | Design | Intervention | Period Sessions | Participants | Sample Size | Age Mean Age (MA) | Follow-Up | Overall Bias |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abdulah et al., 2018 [50] | Iraq | RCT | Painting and handcrafting-based group art therapy | Period: 1 month Sessions: 20 | Patients | 66 | 7–13 MA = 9.5 | 1 week | 90 |

| Hamedi et al., 2020 [49] | Iran | RCT | Conventional CBT and computer CBT | Period: 45-min Sessions: 6 | Patients | 45 | 9–12 MA = 10.5 | Not specified | 92 |

| Kemper et al., 2008 [38] | USA | RCT | Listen to music | Period: 40-min Sessions: 2 | Patients | 63 | 0.8–17.9 MA = 9 | Not specified | 88 (missing data minimised) |

| Lester et al., 2020 [39] | USA, Canada, and Colombia | RCT | Virtual mind–body group program (RY-NF) | Period: 45-min Sessions: 8 | Patients | 51 | 12–17 MA = 14.37 | 6 months | 92 |

| Li et al., 2023 [47] | China | RCT | Child Life intervention | Period: 2 months, 30–40 min Sessions: 16 | Patients | 96 | 8–14 MA = 11 | 3 days | 92 |

| Lyon et al., 2014 [39] | USA | RCT | Family-Centred Advance Care | Period: 60-min Sessions: 3 weeks | Patients and parents | 30 | 14–20 MA = 16.3 | 3 months | 92 |

| Mohammadi et al., 2021 [48] | Iran | RCT | Play-based occupational therapy | Period: 45-min Sessions: 8 | Patients | 25 | 7–12 MA = 9.28 | Not specified | 94 |

| Phipps et al., 2010 [43] | USA and Canada | RCT | Therapeutic massage and humour/relaxation therapy | Period: 30-min 3 times per week Sessions: 4 weeks | Patients and parents | 171 | 6–18 MA = 12.8 | 6 months | 90 |

| Phipps et al., 2012 [37] (follow-up of Phipps et al., 2010 [43]) | USA and Canada | RCT | Therapeutic massage and humour/relaxation therapy | Period: 30-min 3 times per week Sessions: 4 weeks | Patients and survivors | 97 | 6–18 MA = 12.8 | 24 months | 88 (missing data handled) |

| Piasai et al., 2018 [51] | Thailand | RCT | Computer drawing–storytelling and guided imagination with classical music (GIM) | Period: 30-min drawing–storytelling and 30-min GIM | Patients | 40 | 6–12 MA = 9.28 | 1 h | 88 (simple randomisation) |

| Robb et al., 2014 [40] | USA | RCT | Therapeutic Music Video (TMV) intervention | Period: 3 weeks Sessions: 6 | Patients | 113 | 11–24 MA = 17.1 | 100 days | 94 |

| Haase et al., 2020 [35] (follow-up of Robb et al., 2014 [40]) | USA | RCT follow-up | Therapeutic Music Video (TMV) intervention | Period: 3 weeks Sessions: 6 | Patients and survivors | 14 | 13–22 MA = 17 | 5 years | 90 |

| Robb et al., 2016 [41] | USA | Pilot RCT | Active Music Engagement (AME) | Period: 45-min Sessions: 3 | Patients | 16 | 3–8 MA = 5.5 | 30 days | 92 |

| Rosenberg et al., 2019 [53] | USA | RCT | Promoting Resilience in Stress Management (PRISM) | Period: 30-50 min within 2 months Sessions: 7 | Patients | 92 | 12–25 MA = 16.4 | 6 months | 94 |

| Rosenberg et al., 2021 [36] (follow-up of Rosenberg et al., 2019 [53]) | USA | RCT | Promoting Resilience in Stress Management (PRISM) | Period: 30-50 min within 2 months Sessions: 7 | Patients and survivors | 57 | 13–25 MA = 16.4 | 24 months | 92 |

| Shoshani et al., 2016 [52] | Israel | RCT | Make a Wish intervention | Period: 5-6 months Session: 1 | Patients | 66 | 5–12 MA = 11 | 7 months | 92 |

| Yu et al., 2014 [18] | China | RCT | Family-centred Social Adaptation Capability (SAC) | Period: 20-60 min within 12 weeks Session: 4 | Patients | 240 | 3–7 MA = 5 | Not specified | 94 |

| Zhang et al., 2019 [46] | China | RCT | Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) | Period: 5 weeks Sessions: 5 | Patients | 104 | 8–18 MA = 12.4 | 5 weeks | 86 (lack of blinding) |

| Objects | Therapy | Intervention | Measurement | Age Group | Main Psychosocial Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Personality | Art and Music | Music video making (TMV) | Patient interviews | 13–22 | Reflection, self-expression, and finding meaning; overcoming distress; connecting with others; identifying personal strengths |

| SDS, UIS, JCS-R, SPS, FAS, P-ACS, FSS, HRIS, RSTS 1 | 11–24 | Courageous coping, social integration, and family environment | |||

| CBT 2 | CBT | CD-RISC, DASS 3 | 8–18 | Improve resilience and reduce depression, anxiety, and stress | |

| Resilience-Based | Promoting Resilience in Stress Management | CD-RISC, PedsQL, GSCM, KPDS, HADS 4 | 12–25 | Improve resilience, hope, cancer-specific quality of life, and reduce distress | |

| Virtual mind–body group program (RY-NF) | CAMM, MOCS-A, GQ-6, LOT-R 5 | 12–17 | Gratitude, mindfulness, coping abilities and social support | ||

| Emotion | Play-Based | Child Life intervention | Information System, SDSC 6 | 8–14 | Pain, anxiety, fatigue, and sleep disturbance |

| Art and Music | Painting and handcrafting | Parent Interviews, KIHQ 7 | 7–13 | Physical activity, mood, stress levels, and social engagement | |

| Art and Music | Drawing–storytelling and guided imagination | THFS, RS 8, Cortisol levels | 6–12 | Happiness and relaxation | |

| Art and Music | Active Music Engagement (AME) | Parent Interviews FA, PMSSF, IES-R 9 | 3–8 | Emotional distress | |

| Listen to music | HRV, VAS 10 | 0.8–17.9 | Relaxation | ||

| CBT | CBT and computerised version | WBFPRS, CDI, STAEI, STAI 11 | 9–12 | Reduced pain intensity, depression, anger, and anxiety | |

| Massage and Humour | Complementary interventions | CDI, PTSDI, CHQ, BFSC 12 | 6–18 | Depression, PTSD, and quality of life, resilience | |

| Others | Make a Wish | BSI, PedsQLTM4.0, PANAS-C, HHI 13 | 5–12 | Reduce distress, depression, and anxiety. Improve quality of life, hope and positivity | |

| Behaviour | Play-Based | Play-based occupational therapy | TRSC, CPAS, FPS, VAS-F, FAS 14 | 7–12 | Symptoms, pain, anxiety, and fatigue |

| Family-Centred | Family-Centred Advance Care Planning (FACE-TC) | Patient report and interview SQ 15, Five Wishes | 14–20 | Reduce pain, anxiety, fatigue and sleep disturbance | |

| Family-Centred | Family-Centred Social Adaptation Capability (SAC) | Infants-Junior Middle School Student’s SAC Scale | 3–7 | Social adaption capability |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, X.; Chen, H.; Joubert, N.; Tiirola, H. The Mechanism by 18 RCTs Psychosocial Interventions Affect the Personality, Emotions, and Behaviours of Paediatric and Young Adult Cancer Patients: A Systematic Review. Healthcare 2025, 13, 1094. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13101094

Liu X, Chen H, Joubert N, Tiirola H. The Mechanism by 18 RCTs Psychosocial Interventions Affect the Personality, Emotions, and Behaviours of Paediatric and Young Adult Cancer Patients: A Systematic Review. Healthcare. 2025; 13(10):1094. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13101094

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Xiao, Honglin Chen, Natalie Joubert, and Heli Tiirola. 2025. "The Mechanism by 18 RCTs Psychosocial Interventions Affect the Personality, Emotions, and Behaviours of Paediatric and Young Adult Cancer Patients: A Systematic Review" Healthcare 13, no. 10: 1094. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13101094

APA StyleLiu, X., Chen, H., Joubert, N., & Tiirola, H. (2025). The Mechanism by 18 RCTs Psychosocial Interventions Affect the Personality, Emotions, and Behaviours of Paediatric and Young Adult Cancer Patients: A Systematic Review. Healthcare, 13(10), 1094. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13101094