Cross-Cultural Adaptation and Validation of the Portuguese Version of the Multidimensional Scale of Dating Violence 2.0 in Young University Students

Abstract

1. Introduction

The Present Study

2. Materials and Methods

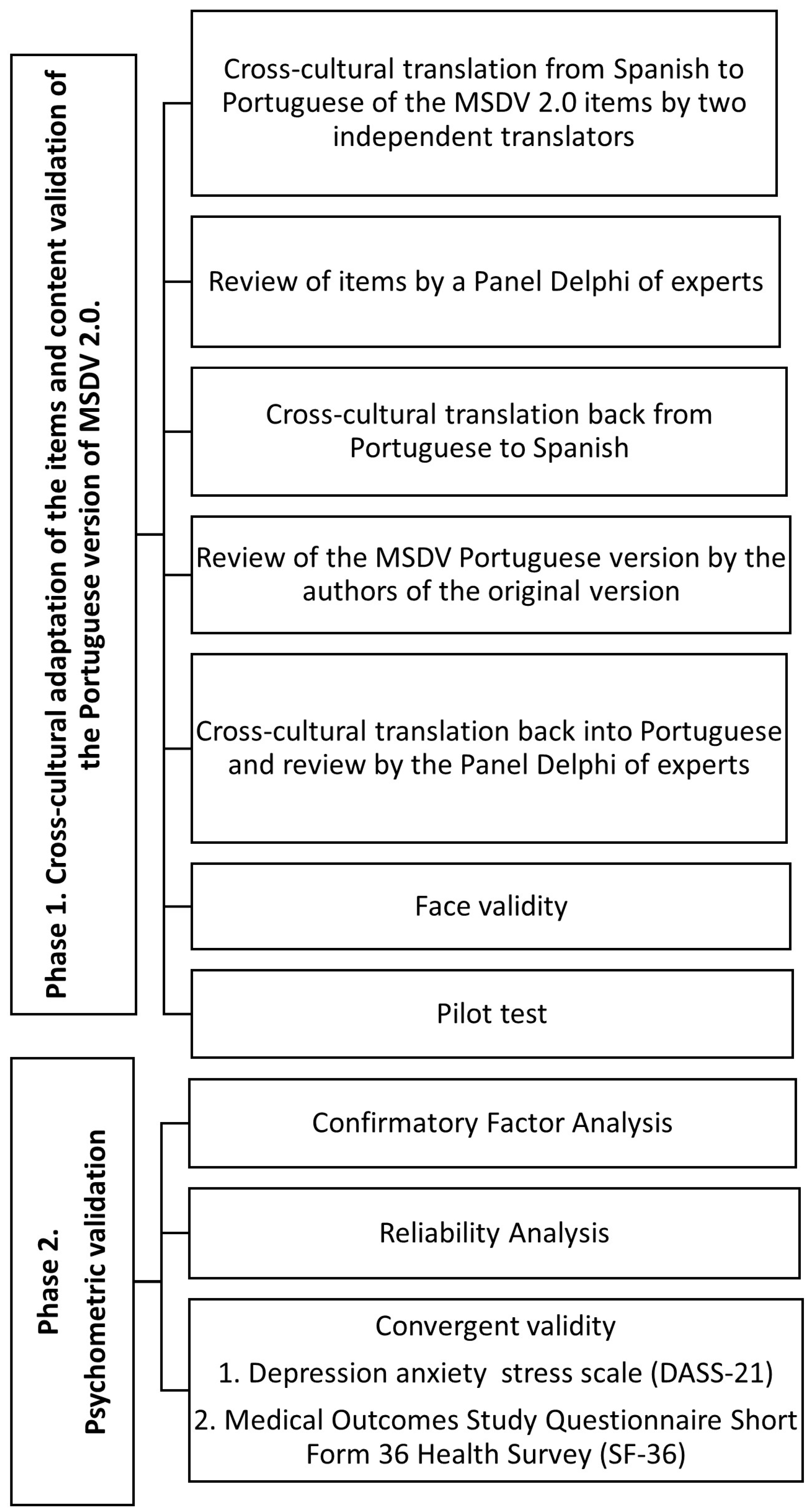

2.1. Research Design

2.1.1. Phase 1. Cross-Cultural Adaptation of the Items and Content Validation of the Portuguese Version of MSDV 2.0

2.1.2. Phase 2. Analysis of Psychometric Properties

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Demographic Variables

2.2.2. Depression, Anxiety, and Stress

2.2.3. Health-Related Quality of Life

2.3. Procedure and Participants

2.4. Data Analysis

2.5. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Characteristics

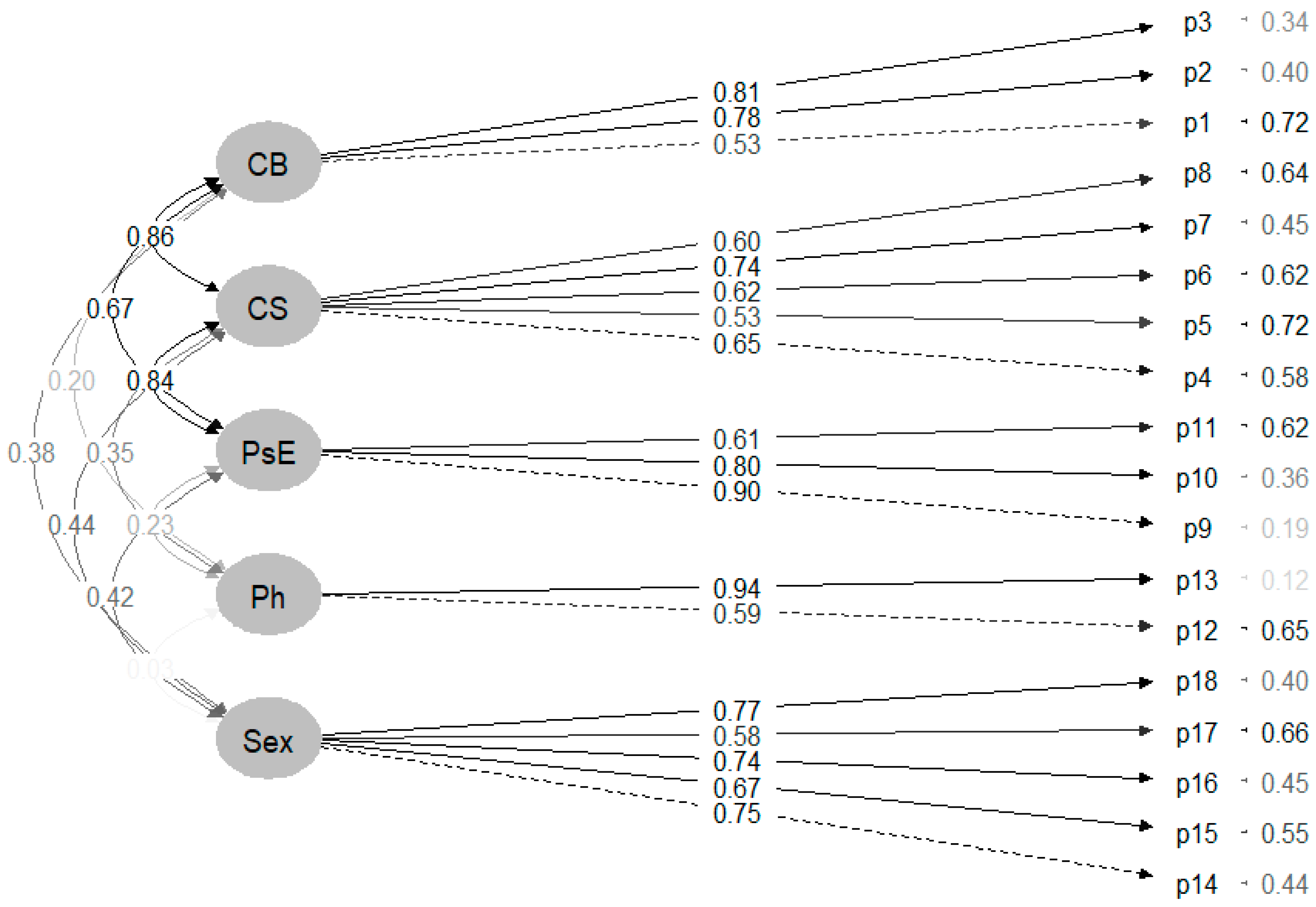

3.2. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

3.3. Convergent Validity

3.4. Reliability—Internal Consistency

3.5. Descriptive of Dating Violence in Young Portuguese University Students

4. Discussion

4.1. Strengths and Limitations

4.2. Involvement in Policy, Practice, and Future Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. COSMIN Risk of Bias Checklist. Evaluating the Portuguese Version of MSDV 2.0

| Psychometric Property | Score | |||

| 1. PROM development | Rater 1 | Rater 2 | Consensus | |

| 1.a | PROM design | V | V | V |

| 1.b | Cognitive interview study or another pilot test | A | A | A |

| TOTAL Lowest score of items 1.a–1.b | A | A | A | |

| 2. Content validity | Rater 1 | Rater 2 | Consensus | |

| 2.a | Asking patients about relevance | V | V | V |

| 2.b | Asking patients about comprehensiveness | V | V | V |

| 2.c | Asking patients about comprehensibility | V | V | V |

| 2.d | Asking professionals about relevance | V | V | V |

| 2.e | Asking professionals about comprehensiveness | V | V | V |

| TOTAL Lowest score of items 2.a–2.e | V | V | V | |

| 3. Structural validity | Rater 1 | Rater 2 | Consensus | |

| 3.1 | For CTT: Was exploratory or confirmatory factor analysis performed? | A | V | A |

| 3.2 | For IRT/Rasch: does the chosen model fit to the research question? | V | V | V |

| 3.3 | Was the sample size included in the analysis adequate? | A | A | A |

| 3.4 | Were there any other important flaws? | A | A | A |

| TOTAL Lowest score of items 1–4 | A | A | A | |

| 4. Internal consistency | Rater 1 | Rater 2 | Consensus | |

| 4.1 | Was an internal consistency statistic calculated for each unidimensional (sub)scale separately? | V | V | V |

| 4.2 | For continuous scores: Was Cronbach’s alpha or omega calculated? | V | V | V |

| 4.3 | For dichotomous scores: Was Cronbach’s alpha or KR-20 calculated? | V | V | V |

| 4.4 | For IRT-based scores: Was standard error of the theta (SE (θ)) or reliability coefficient of estimated latent trait value (index of (subject or item) separation) calculated? | |||

| 4.5 | Were there any other important flaws? | V | V | V |

| TOTAL Lowest score of items 1–5 | V | V | V | |

| 5. Cross-cultural validity/measurement invariance | Rater 1 | Rater 2 | Consensus | |

| 5.1 | Were the samples similar for relevant characteristics except for the group variable? | A | A | A |

| 5.2 | Was an appropriate approach used to analyse the data? | V | A | A |

| 5.3 | Was the sample size included in the analysis adequate? | A | A | A |

| 5.4 | Were there any other important flaws? | V | V | V |

| TOTAL Lowest score of items 1–4 | A | A | A | |

| 6. Reliability | NT | |||

| 7. Measurement error | NT | |||

| 8. Criterion validity | NT | |||

| 9. Hypotheses testing for construct validity | ||||

| 9a. Comparison with other outcome measurement instruments (convergent validity) | Rater 1 | Rater 2 | Consensus | |

| 9.a.1 | Is it clear what the comparator instrument(s) measure(s)? | V | V | V |

| 9.a.2 | Were the measurement properties of the comparator instrument(s) adequate? | A | A | A |

| 9.a.3 | Was the statistical method appropriate for the hypotheses to be tested? | V | V | V |

| 9.a.4 | Were there any other important flaws? | A | V | A |

| TOTAL Lowest score of items 1–4 | A | A | A | |

| 9b. Comparison between subgroups (discriminative or known-groups validity) | NT | |||

| 10. Responsiveness | NT | |||

| Score: V: very good; A: adequate; D: doubtful; I: inadequate; N: not applicable. Not rated (NT): Only those parts of the boxes need to be completed for which its psychometric property has been realised. | ||||

References

- Makepeace, J.M. Courtship Violence among College Students. Fam. Relat. 1981, 30, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarriño-Concejero, L.; Gil-García, E.; Barrientos-Trigo, S.; García-Carpintero-Muñoz, M.L.Á. Instruments used to measure dating violence: A systematic review of psychometric properties. J. Adv. Nurs. 2023, 79, 1267–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Teen Newsletter March 2021-Tenn Dating Violence. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/museum/education/newsletter/2021/mar/#introduction%E2%80%93teen-dating-violence (accessed on 4 June 2023).

- Rubio-Garay, F.; Carrasco, M.Á.; Amor, P.J.; y López-González, M.A. Factores asociados a la violencia en el noviazgo entre adolescentes: Una revisión crítica (Adolescent dating violence related factors: A critical review). Anu. Psicol. Jurídica 2015, 25, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emelianchik-Key, K.; Hays, D.G.; Hill, T. Initial development of the teen screen for dating violence: Exploratory factor analysis, rasch model, and psychometric data. Meas. Eval. Couns. Dev. 2018, 51, 16–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oram, S.; Fisher, H.L.; Minnis, H.; Seedat, S.; Walby, S.; Hegarty, K.; Rouf, K.; Angénieux, C.; Callard, F.; Chandra, P.S.; et al. The Lancet Psychiatry Commission on intimate partner violence and mental health: Advancing mental health services, research, and policy. Lancet Psychiatry 2022, 9, 487–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights. Violence against Women: An EU-Wide Survey. Results at a Glance. Available online: https://fra.europa.eu/en/publication/2014/violence-against-women-eu-wide-survey-results-glance (accessed on 7 June 2023).

- Lisboa, M.R.; Teixeira, A.L.; Cerejo, D. Inquérito Municipal à Violência Doméstica e de Género no Concelho de Lisboa; Observatório Nacional de Violência e Género: Lisboa, Portugal, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Lisboa, M.; Cerejo, D.; Rosa, R.; Teixeira, A.L.; Nóvoa, T.; Neves, R. 2º Inquérito à Violência de Género—Região Autónoma dos Açores; Observatório Nacional de Violência e Género: Lisboa, Portugal, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Lisboa, M.; Cerejo, D.; Teixeira, A.L.; Rosa, R.; Queirós, M.; Torgal, J.; Pinhão, M.; Jesus, M.O. Impacto da COVID-19 na Violência Contra as Mulheres: Uma Análise Longitudinal. Relatório Final; Observatório Nacional de Violência e Género: Lisboa, Portugal, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Women’s Union Alternative and Response [UMAR]. National Study on Dating Violence. UMAR/CIG. 2024. Available online: https://www.cig.gov.pt/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/INFO_ARTHEMIS_UMAR_2024_v002_compressed.pdf (accessed on 20 March 2024).

- García-Carpintero, M.Á.; Rodríguez, J.; Porcel, A.M. Diseño y validación de la escala para la detección de violencia en el noviazgo en jóvenes en la Universidad de Sevilla. Gac. Sanit. 2018, 32, 121–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bagwell-Gray, M.E. Women’s Experiences of Sexual Violence in Intimate Relationships: Applying a New Taxonomy. J. Interpers. Violence 2021, 36, 13–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabelas, J.; Marta, C. La era TRIC: Factor R-Elacional y Educomunicación; Ediciones Egregius. 2020. Available online: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/libro?codigo=826774 (accessed on 20 March 2024).

- Estébanez, I. La Ciber Violencia Hacia las Adolescentes en Las Redes Sociales; Instituto Andaluz de la Mujer, Consejería de Igualdad y Políticas Sociales: Sevilla, Spain, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez, C.; Durán, M.; Martínez, R. Cyber aggressors in dating relationships and its relation with psychological violence, sexism and jealousy. Health Addict. 2018, 18, 17–27. [Google Scholar]

- Park, Y.; Mulford, C.; Blachman-Demner, D. The Acute and Chronic Impact of Adolescent Dating Violence: A Public Health Perspective. In Adolescent Dating Violence; Wolfe, D.A., Temple, J.R., Eds.; Academic Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2018; pp. 53–83. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrer-Pérez, V.A.; Bosch-Fiol, E. Gender in the analysis of intimate partner violence against women: From gender “blindness” to gender-specific research. Anuario de Psicología Jurídica 2023, 29, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schubert, K. Building a culture of health: Promoting healthy relationships and reducing teen dating violence. J. Adolesc. Health 2015, 56 (Suppl. S2), S3–S4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piolanti, A.; Waller, F.; Schmid, I.E.; Foran, H.M. Long-term Adverse Outcomes Associated with Teen Dating Violence: A Systematic Review. Pediatrics 2023, 151, e2022059654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woolweaver, A.B.; Abu Khalaf, N.; Espelage, D.L.; Zhou, Z.; Reynoso-Marmolejos, R.; Calnan, M.; Mirsen, R. Outcomes Associated with Adolescent Dating and Sexual Violence Victimization: A Systematic Review of School-Based Literature. Trauma Violence Abus. 2024. ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malherbe, I.; Delhaye, M.; Kornreich, C.; Kacenelenbogen, N. Teen Dating Violence and Mental Health: A Review. Psychiatr. Danub. 2023, 35 (Suppl. S2), 155–159. [Google Scholar]

- Burton, C.W.; Halpern-Felsher, B.; Rehm, R.S.; Rankin, S.H.; Humphreys, J.C. Depression and Self-Rated Health Among Rural Women Who Experienced Adolescent Dating Abuse: A Mixed Methods Study. J. Interpers. Violence 2016, 31, 920–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Exner-Cortens, D.; Eckenrode, J.; Rothman, E. Longitudinal associations between teen dating violence victimization and adverse health outcomes. Pediatrics 2013, 131, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haynie, D.L.; Farhat, T.; Brooks-Russell, A.; Wang, J.; Barbieri, B.; Iannotti, R.J. Dating violence perpetration and victimization among U.S. adolescents: Prevalence, patterns, and associations with health complaints and substance use. J. Adolesc. Health 2013, 53, 194–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, F.A.; Howard, D.E.; Beck, K.H.; Shattuck, T.; Hallmark-Kerr, M. Psychosocial correlates of physical dating violence victimization among Latino early adolescents. J. Interpers. Violence 2010, 25, 808–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campo-Tena, L.; Larmour, S.R.; Pereda, N.; Eisner, M.P. Longitudinal Associations Between Adolescent Dating Violence Victimization and Adverse Outcomes: A Systematic Review. Trauma Violence Abus. 2023, 25, 15248380231174504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ackard, D.M.; Eisenberg, M.E.; Neumark-Sztainer, D. Long-term impact of adolescent dating violence on the behavioural and psychological health of male and female youth. J. Pediatr. 2007, 151, 476–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverman, J.G.; Raj, A.; Mucci, L.A.; Hathaway, J.E. Dating violence against adolescent girls and associated substance use, unhealthy weight control, sexual risk behaviour, pregnancy, and suicidality. JAMA 2001, 286, 572–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedina, L.; Howard, D.E.; Wang, M.Q.; Murray, K. Teen Dating Violence Victimization, Perpetration, and Sexual Health Correlates Among Urban, Low-Income, Ethnic, and Racial Minority Youth. Int. Q. Community Health Educ. 2016, 37, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raible, C.A.; Dick, R.; Gilkerson, F.; Mattern, C.S.; James, L.; Miller, E. School nurse-delivered adolescent relations-hip abuse prevention. J. Sch. Health 2017, 87, 524–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, J.; Fabelo, H.; Rodríguez, L.; Rodríguez, F. The Dating Violence Questionnaire: Validation of the Cuestionario de Violencia de Novios Using a College Sample from the United States. Violence Vict. 2016, 31, 438–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aizpitarte, A.; Alonso, I.; de Vijver, F.J.R.; Perdomo, M.C.; Galvez-Sobral, J.A.; Garcia-Lopez, E. Development of a Dating Violence Assessment Tool for Late Adolescence Across Three Countries: The Violence in Adolescents’ Dating Relationships Inventory (VADRI). J. Interpers. Violence 2017, 32, 2626–2646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothman, E.F.; Cuevas, C.A.; Mumford, E.A.; Bahrami, E.; Taylor, B.G. The Psychometric Properties of the Measure of Adolescent Relationship Harassment and Abuse (MARSHA) With a Nationally Representative Sample of U.S. Youth. J. Interpers. Violence 2021, 37, NP9712–NP9737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soriano, E.; Sanabria, M.; Cala, V.C. Design, and validation of the scale TDV-VP teen dating violence: Victimisation and perpetration for Spanish speakers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Díaz, J.F.; Herrero, J.; Rodriguez-Franco, L.; Bringas-Molleda, C.; Paino-Quesada, S.G.; Perez, B. Validation of Dating Violence Questionnaire-R (DVQ-R). Int. J. Clin. Health Psychol. 2017, 17, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, L.; Wekerle, C.; Goldstein, A.L. Measuring adolescent dating violence: Development of “conflict in adolescent dating relationships inventory” short form. Adv. Ment. Health 2012, 11, 35–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronzón, R.C.; Muñoz-Rivas, M.J.; Zamarrón Cassinello, M.D.; Redondo Rodríguez, N. Cultural Adaptation of the Modified Version of the Conflicts Tactics Scale (M-CTS) in Mexican Adolescents. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, M.L.; Leigh, I.W. Intimate Partner Violence Against Deaf Female College Students. Violence Women 2011, 17, 822–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Carpintero-Muñoz, M.Á.; Tarriño-Concejero, L.; Gil-García, E.; Pórcel-Gálvez, A.M.; Barrientos-Trigo, S. Short version of the Multidimensional Scale of Dating Violence (MSDV 2.0) in Spanish-language: Instrument development and psychometric evaluation. J. Adv. Nurs. 2022, 79, 1610–1631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Violence against Women. Key Facts. 2021. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/violence-against-women (accessed on 2 January 2024).

- Arroyo-Acevedo, H.; Landazabal, G.D.; Pino, C.G. Ten years of the movement of universities promoting the health of Latin America and the contribution of the red IberoAmerican platform of Universities Promoting the Health of Latin America. Glob. Health Promot. 2015, 22, 64–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Riera, J.R.; Gallardo, C.; Aguilo, A.; Granado, M.C.; Lopez-Gomez, J.; Arroyo-Acevedo, H.V. The university as a community: Health-promoting universities. SESPAS Report. Gac. Sanit. 2018, 32, 86–91. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Ibero-American Network of Health Promoting Universities. Available online: https://www3.paho.org/hq/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=10675:2015-iberoamerican-network-of-health-promoting-universitiesriups&Itemid=820&lang=es (accessed on 14 December 2023).

- Mokkink, L.; Princen, C.A.; Patrick, D.; Alonso, J.; Bouter, L.M.; de Vet, H.; Terwee, C.B. COSMIN Study Design Checklist for Patient-Reported Outcome Measurement Instruments. Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics Amsterdam Public Health Research Institute Amsterdam University Medical Centers. 2019. Available online: https://www.cosmin.nl/wp-content/uploads/COSMIN-study-designing-checklist_final.pdf (accessed on 6 December 2023).

- Cruz, Ó.A.; Muñoz, A.I. Validación de instrumento para identificar el nivel de vulnerabilidad de los trabajadores de la salud a la tuberculosis en instituciones de salud (IVTS TB-001). Med. Segur. Trab. 2015, 61, 448–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abad, F.; Olea, J.; Ponsoda, V.; García, C. Measurement in Social and Health Sciences; Síntesis Publisher: Madrid, Spain, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Van Teijlingen, E.R.; Hundley, V. The importance of pilot studies. Nurs. Stand. 2002, 16, 33–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pais-Ribeiro, J.L.; Honrado, A.; Leal, I. Contribution to the study of the Portuguese adaptation of the anxiety, depression, and stress scales (DASS) of 21 items of lovibond and lovibond. Psicol. Saúde Doencas 2004, 5, 229–239. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira, P.L. Development of the Portuguese version of MOS SF-36. Part II—Validation tests. Acta Med. Port. 2000, 13, 119–127. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, T.A. Confirmatory Factor Analysis for Applied Research, 2nd ed.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Hefetz, A.; Liberman, G. Applying structural equation modelling in educational research. Cult. Educ. 2017, 29, 563–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schermelleh-Engel, K.; Moosbrugger, H.; Müller, H. Evaluating the Fit of Structural Equation Models: Tests of Significance and Descriptive Goodness-of-Fit Measures. Methods Psychol. Res. 2003, 8, 23–74. [Google Scholar]

- Tucker, L.R.; Lewis, C. A reliability coefficient for maximum likelihood factor analysis. Psychometrika 1973, 38, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, R.; Fernández, C.; Baptista, L. Research Methodology; McGraw-Hill: México City, México, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Nunnally, J.C.; Bernstein, I.H. Psychometric Theory; McGraw-Hill, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Domínguez-Lara, S. Fiabilidad y alfa ordinal. Actas Urológicas Españolas 2018, 42, 140141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarriño-Concejero, L.; García-Carpintero-Muñoz, M.L.Á.; Barrientos-Trigo, S.; Gil-García, E. Dating violence and its relationship with anxiety, depression, and stress in young Andalusian university students. Enferm. Clin. 2023, 33, 47–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lara, L.; López-Cepero, J. Psychometric properties of the dating violence questionnaire: Reviewing the evidence in Chilean Youths. J. Interpers. Violence 2021, 36, 2373–2392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldeira, S.; Silva, O.; Mendes, M.; Botelho, S.; Martis, M.J. University Student’s perceptions of hazing: A gender approach. Int. J. Dev. Res. 2016, 6, 9444–9449. [Google Scholar]

| Portuguese Version MSDV 2.0 | Spanish Version MSDV 2.0 | D |

|---|---|---|

|

| CB |

|

| CB |

|

| CB |

|

| CS |

|

| CS |

|

| CS |

|

| PsE |

|

| PsE |

|

| PsE |

|

| PsE |

|

| PsE |

|

| Ph |

|

| Ph |

|

| Sex |

|

| Sex |

|

| Sex |

|

| Sex |

|

| Sex |

| Variables | Women (n = 151) | Men (n = 55) | Total (n = 206) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (M; SD) | 20.01; SD = 1.74 | 20.35; SD = 2.11 | 20.10; SD = 1.84 |

| Residence | |||

| Urban (n; %) | 141; 93.4% | 49; 89% | 190; 92.2% |

| Rural (n; %) | 10; 6.6% | 6; 11% | 16; 7.8% |

| Social/Financial support from the university (scholarship, housing) | 42; 27.8% | 9; 16.4% | 51; 24.8% |

| Work (active) (M; SD) | 34 (22.5%) | 13 (23.6%) | 47 (22.8%) |

| Weekly hours (M; SD) | 6.2; SD = 13.2 | 6.39; SD = 12.76 | 6.25; SD = 12.43 |

| Average time (months) in a dating relationship (M; SD) | 20.64; SD= 17.59 | 15.96; SD = 15.40 | 19.40; SD = 17.12 |

| Dating relationships in the last year (M; SD) | 1.07; SD = 0.28 | 1.05; SD = 0.23 | 1.06; SD = 0.26 |

| Currently in a romantic relationship (Mean, SD) | 50 (33.11%) | 27 (49.1%) | 77 (37.38%) |

| Living with a partner (Mean, SD) | 11 (7.28%) | 5 (9.1%) | 16 (7.8%) |

| MSDV 2.0 Cyberbullying | MSDV 2.0 Control and Surveillance | MSDV 2.0 Psycho-Emotional | MSDV 2.0 Physical | MSDV 2.0 Sexual | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DASS-21 (Depression) | 0.25 ** | 0.34 ** | 0.30 ** | 0.16 * | 0.30 ** |

| DASS-21 (Anxiety) | 0.33 ** | 0.35 ** | 0.36 ** | 0.19 ** | 0.31 ** |

| DASS-21 (Stress) | 0.32 ** | 0.32 ** | 0.35 ** | 0.19 ** | 0.32 ** |

| SF-36 (Physical function) | −0.06 | −0.16 * | −0.14 * | −0.09 | −0.018 * |

| SF-36 (Physical role) | −0.07 | −0.13 | −0.09 | 0.04 | −0.25 ** |

| SF-36 (Body pain) | −0.016 * | −0.10 | −0.09 | −0.06 | −0.20 ** |

| SF-36 (General health) | −0.07 | −0.11 | −0.09 | −0.06 | −0.14 * |

| SF-36 (Vitality) | −0.21 ** | −0.24 ** | −0.20 ** | −0.03 | −0.25 ** |

| SF-36 (Social function) | −0.24 ** | −0.22 ** | −0.19 ** | −0.05 | −0.25 ** |

| SF-36 (Emotional role) | −0.22 ** | −0.27 ** | −0.23 ** | 0.06 | −0.29 ** |

| SF-36 (Mental health) | −0.25 ** | −0.30 ** | −0.21 ** | −0.07 | −0.26 ** |

| Dimensions MSDV 2.0 | Cronbach’s Alpha | Ordinal Alpha | McDonald’s Omega | Greatest Lower Bound | Explained Variance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cyberbullying | 0.74 | 0.79 | 0.76 | 0.77 | 0.76 |

| Control and surveillance | 0.76 | 0.83 | 0.77 | 0.81 | 0.42 |

| Psycho-emotional | 0.81 | 0.86 | 0.82 | 0.85 | 0.61 |

| Physical | 0.70 | - | 0.82 | - | 0.73 |

| Sexual | 0.81 | 0.91 | 0.83 | 0.87 | 0.51 |

| Total | 0.88 | 0.9 | 0.91 | 0.93 | - |

| Items | Total (n = 206) | Women (n = 151) | Men (n = 55) | p * | Dimensions | Score Range | Total (n = 206) | Women (n = 151) | Men (n = 55) | p * | Percentage of Youth Who Experienced Dating Violence (At Least 1–2 Times) (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | ||||||

| 2.77 (1.43) | 2.85 (1.41) | 2.55 (1.47) | 0.154 | Cyberbullying | 3–15 | 7.47 (3.43) | 7.89 (3.47) | 6.31 (3.08) | 0.003 | |

| 2.33 (1.39) | 2.51 (1.40) | 1.82 (1.20) | <0.001 | 63.93 | ||||||

| 2.37 (1.43) | 2.52 (1.45) | 1.95 (1.28) | 0.008 | |||||||

| 1.91 (1.12) | 2.05 (1.19) | 1.55 (0.78) | 0.010 | Control and surveillance | 5–25 | 9.65 (4.25) | 10.20 (4.48) | 8.14 (3.08) | 0.004 | 46.02 |

| 1.69 (1.08) | 1.79 (1.07) | 1.42 (1.05) | 0.003 | |||||||

| 2.28 (1.35) | 2.34 (1.37) | 2.11 (1.30) | 0.245 | |||||||

| 2.34 (1.46) | 2.50 (1.49) | 1.91 (1.25) | 0.011 | |||||||

| 1.42 (0.87) | 1.52 (0.95) | 1.16 (0.53) | 0.006 | |||||||

| 2.29 (1.39) | 2.53 (1.44) | 1.62 (0.93) | <0.001 | Psycho-emotional | 3–15 | 6.79 (3.51) | 7.34 (3.63) | 5.29 (2.65) | <0.001 | |

| 2.25 (1.38) | 2.44 (1.43) | 1.73 (1.08) | <0.001 | 57.46 | ||||||

| 2.26 (1.34) | 2.38 (1.38) | 1.95 (1.19) | 0.043 | |||||||

| 1.04 (0.30) | 1.06 (0.35) | 1.00 (0.00) | 0.173 | Physical | 2–10 | 2.17 (0.70) | 2.20 (0.79) | 2.10 (0.37) | 0.927 | 5.55 |

| 1.13 (0.49) | 1.14 (0.53) | 1.11 (0.37) | 0.944 | |||||||

| 1.24 (0.61) | 1.32 (0.68) | 1.00 (0.00) | <0.001 | Sexual | 5–25 | 6.66 (2.94) | 7.26 (3.25) | 5.13 (0.39) | <0.001 | |

| 1.14 (0.52) | 1.19 (0.59) | 1.02 (0.14) | 0.026 | |||||||

| 1.37 (0.84) | 1.49 (0.95) | 1.054 (0.19) | <0.001 | 20.28 | ||||||

| 1.41 (0.86) | 1.54 (0.96) | 1.05 (0.23) | <0.001 | |||||||

| 1.50 (0.98) | 1.68 (1.08) | 1.02 (0.14) | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tarriño-Concejero, L.; Cerejo, D.; Arnedillo-Sánchez, S.; Praena-Fernández, J.M.; García-Carpintero Muñoz, M.Á. Cross-Cultural Adaptation and Validation of the Portuguese Version of the Multidimensional Scale of Dating Violence 2.0 in Young University Students. Healthcare 2024, 12, 759. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12070759

Tarriño-Concejero L, Cerejo D, Arnedillo-Sánchez S, Praena-Fernández JM, García-Carpintero Muñoz MÁ. Cross-Cultural Adaptation and Validation of the Portuguese Version of the Multidimensional Scale of Dating Violence 2.0 in Young University Students. Healthcare. 2024; 12(7):759. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12070759

Chicago/Turabian StyleTarriño-Concejero, Lorena, Dalila Cerejo, Socorro Arnedillo-Sánchez, Juan Manuel Praena-Fernández, and María Ángeles García-Carpintero Muñoz. 2024. "Cross-Cultural Adaptation and Validation of the Portuguese Version of the Multidimensional Scale of Dating Violence 2.0 in Young University Students" Healthcare 12, no. 7: 759. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12070759

APA StyleTarriño-Concejero, L., Cerejo, D., Arnedillo-Sánchez, S., Praena-Fernández, J. M., & García-Carpintero Muñoz, M. Á. (2024). Cross-Cultural Adaptation and Validation of the Portuguese Version of the Multidimensional Scale of Dating Violence 2.0 in Young University Students. Healthcare, 12(7), 759. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12070759