Psychosocial Adjustment Factors Associated with Child–Parent Violence: The Role of Family Communication and a Transgressive Attitude in Adolescence

Abstract

1. Introduction

The Current Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Mesures

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Pearsons Correlation

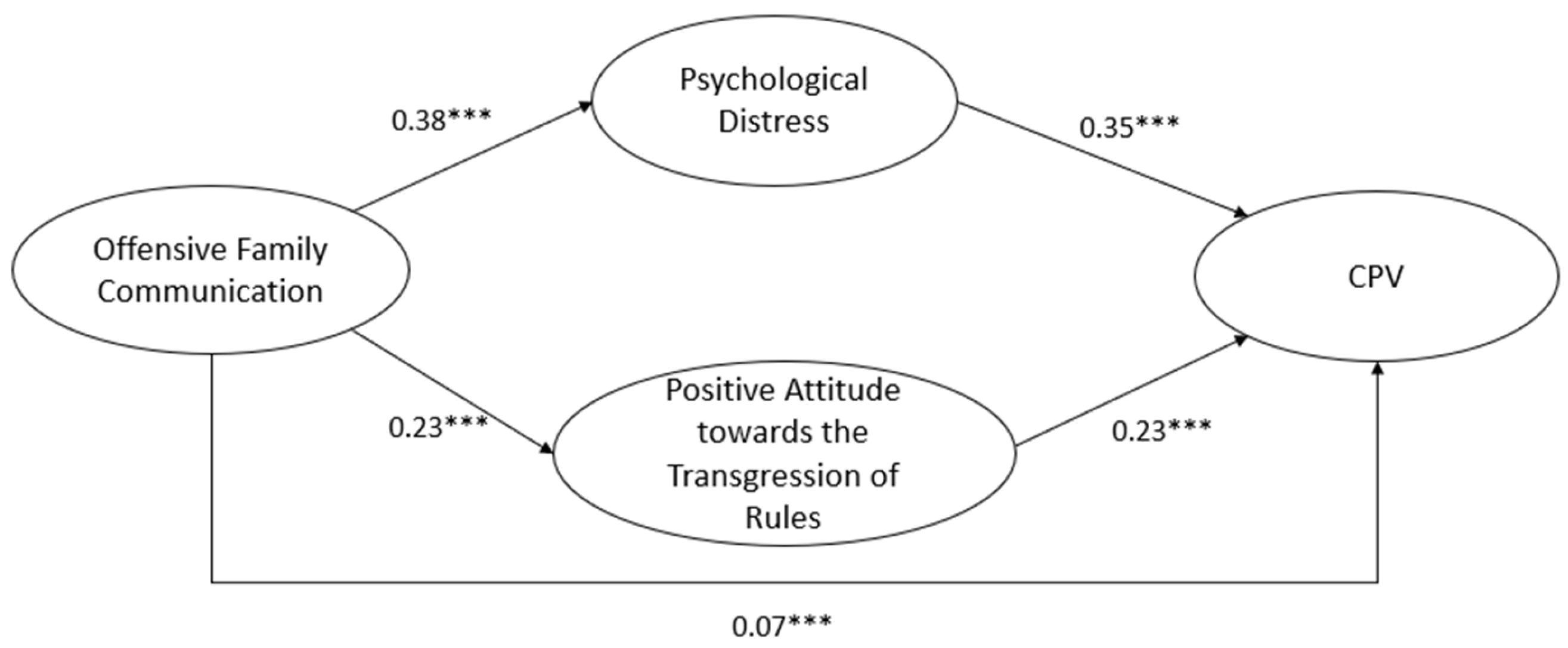

3.2. Direct and Indirect Effects

3.3. Moderating Effect of Gender

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pereira, R.; Loinaz Calvo, I.; Bilbao, H.; Arrospide, J.; Bertino, L.; Calvo, A.; Gutiérrez, M.M. Propuesta de definición de violencia filio-parental: Consenso de la Sociedad Española para el estudio de la Violencia filio-parental (SEVIFIP). Papeles Psicólogo—Psychol. Pap. 2017, 38, 216–223. [Google Scholar]

- Suárez-Relinque, C.; Arroyo, G.d.M.; León-Moreno, C.; Jerónimo, J.E.C. Child-to-parent violence: Which parenting style is more protective? A study with spanish adolescents. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cottrell, B. Parent Abuse: The Abuse of Parents by Their Teenage Children; Government of Canada Publications: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2003; ISBN 0662295293. [Google Scholar]

- Arias-Rivera, S.; García, V.H. Theoretical framework and explanatory factors for child-to-parent violence. A scoping review. An. Psicol. 2020, 36, 220–231. [Google Scholar]

- Contreras, L.; Rodríguez-Díaz, F.J.; Cano-Lozano, M.C. Prevalence and reasons for child-to-parent violence in Spanish adolescents: Gender differences in victims and aggressors. In Colección Psicología y Ley; Universidad de la Rioja: Logroño, Spain, 2020; pp. 177–190. [Google Scholar]

- Suarez Relinque, C.; Moral-Arroyo, G. del Child-to-parent cyber violence: What is the next step? J. Fam. Violence 2023, 38, 301–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyons, J.; Bell, T.; Fréchette, S.; Romano, E. Child-to-Parent Violence: Frequency and Family Correlates. J. Fam. Violence 2015, 30, 729–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallego, R.; Novoa, M.; Fariña, F.; Arcea, R. Child-to-parent Violence and Parent-to-child Violence: A Meta-analytic Review. Eur. J. Psychol. Appl. Leg. Context 2019, 11, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvete, E.; Orue, I.; Fernández-González, L.; Chang, R.; Little, T.D. Longitudinal Trajectories of Child-to-Parent Violence through Adolescence. J. Fam. Violence 2020, 35, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibabe, I. Adolescent-to-parent violence and family environment: The perceptions of same reality? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rico, E.; Rosado, J.; Cantón-Cortés, D. Impulsiveness and Child-to-Parent Violence: The Role of Aggressor’s Sex. Span. J. Psychol. 2017, 20, E15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. Ecological models of human development. In International Encyclopedia of Education; Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 1994; ISBN 0716728605. [Google Scholar]

- Soyer, G.F. Book Review: The Ecology of Human Development by Urie Bronfenbrenner. J. Cult. Values Educ. 2019, 2, 77–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hereyah, Y.; Purwanti, A. Family Communication on Single-Parenting Families in Maintaining Relationships and Shaping Children’s Self-Concepts. Ilkogr. Online 2021, 20, 380. [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez, T.; Murgui, S.; Musitu, G. Comunicación familiar y ánimo depresivo: El papel mediador de los recursos psicosociales del adolescente. Rev. Mex. Psicol. 2007, 24, 259–271. [Google Scholar]

- Olson, D.H. Circumplex Model of Marital and Family Sytems. J. Fam. Ther. 2000, 22, 144–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro-Castañeda, R.; Núñez-Fadda, S.M.; Musitu, G.; Callejas-Jerónimo, J.E. Comunicación con los padres, malestar psicológico y actitud hacia la autoridad en adolescentes mexicanos: Su influencia en la victimización escolar. Estud. Sobre Educ. 2019, 36, 113–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez, T.I.; Estévez, E.; Velilla, C.M.; Martín-Albo, J.; Martínez, M.L. Family Communication and Verbal Child-to-Parent Violence among Adolescents: The Mediating Role of Perceived Stress. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 4538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-Martínez, P.; Montero-Montero, D.; Moreno-Ruiz, D.; Martínez-Ferrer, B. The Role of Parental Communication and Emotional Intelligence in Child-to-Parent Violence. Behav. Sci. 2019, 9, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortina, H.; Martín, A.M. The behavioral specificity of child-to-parent violence. An. Psicol. 2020, 36, 386–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Álvarez, M.; Morán Rodríguez, N.; García-Vera, M.P. Violencia de hijos a padres: Revisión teórica de las variables clínicas descriptoras de los menores agresores. Psicopatol. Clin. Leg. Forense 2011, 11, 101–121. [Google Scholar]

- Cummings, C.M.; Caporino, N.E.; Kendall, P.C. Comorbidity of anxiety and depression in children and adolescents: 20 years after. Psychol. Bull. 2014, 140, 816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keles, B.; McCrae, N.; Grealish, A. A systematic review: The influence of social media on depression, anxiety and psychological distress in adolescents. Int. J. Adolesc. Youth 2020, 25, 79–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rea, H.M.; Factor, R.S.; Kao, W.; Shaffer, A. A meta-analytic review of the five minute speech sample as a measure of family emotional climate for youth: Relations with internalizing and externalizing symptomatology. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 2020, 51, 656–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holfeld, B.; Baitz, R. The mediating and moderating effects of social support and school climate on the association between cyber victimization and internalizing symptoms. J. Youth Adolesc. 2020, 49, 2214–2228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Curran, T.; Allen, J. Family Communication Patterns, Self-Esteem, and Depressive Symptoms: The Mediating Role of Direct Personalization of Conflict. Commun. Rep. 2017, 30, 80–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrodt, P.; Ledbetter, A.M. Communication processes that mediate family communication patterns and mental well-being: A mean and covariance structures analysis of young adults from divorced and nondivorced families. Hum. Commun. Res. 2007, 33, 330–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cénat, J.M.; Hébert, M.; Blais, M.; Lavoie, F.; Guerrier, M.; Derivois, D. Cyberbullying, psychological distress and self-esteem among youth in Quebec schools. J. Affect. Disord. 2014, 169, 7–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morelli, M.; Bianchi, D.; Baiocco, R.; Pezzuti, L.; Chirumbolo, A. Sexting, psychological distress and dating violence among adolescents and young adults. Psicothema 2016, 28, 137–142. [Google Scholar]

- Ibabe, I.; Jaureguizar, J. ¿Hasta qué punto la violencia filio-parental es bidireccional? An. Psicol. 2011, 27, 265–277. [Google Scholar]

- Ibabe, I.; Arnoso, A.; Elgorriaga, E. Behavioral problems and depressive symptomatology as predictors of child-to-parent violence. Eur. J. Psychol. Appl. Leg. Context 2014, 6, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Abrio, A.; Martínez-Ferrer, B.; Sánchez-Sosa, J.C.; Musitu, G. A psychosocial analysis of relational aggression in Mexican adolescents based on sex and age. Psicothema 2019, 31, 88–93. [Google Scholar]

- Emler, N.; Reicher, S. Adolescence and Delinquency: The Collective Management of Reputation; Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 1995; Volume xiv, ISBN 978-0-631-13802-0/978-0-631-16823-2. [Google Scholar]

- Estévez, E.; Murgui, S.; Moreno, D.; Musitu, G. Estilos de comunicación familiar, actitud hacia la autoridad institucional y conducta violenta del adolescente en la escuela [Family communication styles, attitude towards institutional authority and violent behavior of adolescents in school]. Psicothema 2007, 19, 108–113. [Google Scholar]

- Carrascosa, L.; Cava, M.J.; Buelga, S. Actitudes hacia la autoridad y violencia entre adolescentes: Diferencias en función del sexo [Attitudes towards authority and violence among adolescents: Differences according to sex]. Suma Psicológ. 2015, 22, 102–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emler, N.; Reicher, S. Delinquency: Cause or consequence of social exclusion. In The Social Psychology of Inclusion and Exclusion; Psychology Press: London, UK, 2005; pp. 211–241. ISBN 0203496175. [Google Scholar]

- Ortega-Barón, J.; Buelga, S.; Caballero, M.J.C.; Torralba, E. School violence and attitude toward authority of student perpetrators of cyberbullying. Rev. Psicodidact. 2017, 22, 23–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Moral, G.; Suárez-Relinque, C.; Callejas, J.E.; Musitu, G. Child-to-parent violence: Attitude towards authority, social reputation and school climate. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Ferrer, B.; Romero-Abrio, A.; Moreno-Ruiz, D.; Musitu, G. Child-to-parent violence and parenting styles: Its relations to problematic use of social networking sites, alexithymia, and attitude towards institutional authority in adolescence. Psychosoc. Interv. 2018, 27, 163–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buelga, S.; Martínez-Ferrer, B.; Musitu, G. Family relationships and cyberbullying. In Cyberbullying Across the Globe: Gender, Family, and Mental Health; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015; pp. 99–114. ISBN 9783319255521. [Google Scholar]

- Buelga, S.; Martínez–Ferrer, B.; Cava, M.J. Differences in family climate and family communication among cyberbullies, cybervictims, and cyber bully–victims in adolescents. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 76, 164–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garaigordobil, M. A comparative analysis of empathy in childhood and adolescence: Gender differences and associated socio-emotional variables. Int. J. Psychol. Psychol. Ther. 2009, 9, 217–235. [Google Scholar]

- Brewer, G.; Kerslake, J. Cyberbullying, self-esteem, empathy and loneliness. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2015, 48, 255–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garaigordobil, M.; Martinez-Valderrey, V.; Aliri, J. Autoestima, empatía y conducta agresiva en adolescentes víctimas de bullying presencial. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2013, 3, 29–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levant, R.F.; Hall, R.J.; Williams, C.M.; Hasan, N.T. Gender Differences in Alexithymia. Psychol. Men Masculinity 2009, 10, 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cava, M.J.; Estévez, E.; Buelga, S.; Musitu, G. Propiedades psicométricas de la escala de actitudes hacia la autoridad institucional en adolescentes (AAI-A). An. Psicol. 2013, 29, 540–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Espelage, D.L. Ecological Theory: Preventing Youth Bullying, Aggression, and Victimization. Theory Pract. 2014, 53, 257–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cava, M.J.; Buelga, S.; Musitu, G. Parental communication and life satisfaction in adolescence. Span. J. Psychol. 2014, 17, E98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López, E.E.; Olaizola, J.H.; Ferrer, B.M.; Ochoa, G.M. Aggressive and non-aggressive rejected students: An analysis of their differences. Psychol. Sch. 2006, 43, 387–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Abrio, A.; Martínez-Ferrer, B.; Musitu-Ferrer, D.; León-Moreno, C.; Villarreal-González, M.E.; Callejas-Jerónimo, J.E. Family communication problems, psychosocial adjustment and cyberbullying. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Hair, J.F. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling. In Handbook of Market Research; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 1–40. ISBN 10.1108/EBR-10-2013-0128. [Google Scholar]

- Batista-Foguet, J.M.; Coenders, G. Modelos de Ecuaciones Estructurales: Modelos Para el Análisis de Relaciones Causales; Arco Libros: Madrid, Spain, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Bentler, P.M. EQS 6 Structural Equations Program Manual; Multivariate Software, Inc.: Encino, CA, USA, 2006; ISBN 1885898037. [Google Scholar]

- Straus, M.A.; Douglas, E.M. A Short Form of the Revised Conflict Tactics Scales, and Typologies for Severity and Mutuality. Violence Vict. 2004, 19, 507–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Hoyo-Bilbao, J.; Orue, I.; Gámez-Guadixb, M.; Calvete, E. Multivariate models of child-to-mother violence and child-to-father violence among adolescents. Eur. J. Psychol. Appl. Leg. Context 2020, 12, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, H.; Olson, D. Parent adolescent communication scale. In Family Inventories; Olson, D.H., Ed.; Family Social Sciences, University of Minnesota: St. Paul, MN, USA, 1982; pp. 145–182. [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez, T.I.; Musitu, G.; Ramos, M.J.; Murgui, S. Community involvement and victimization at school: An analysis through family, personal and social adjustment. J. Community Psychol. 2009, 37, 959–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessler, R.; Mroczek, D. Final Version of Our Non-Specific Psychological Distress Scale; Survey Research Center of the Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2013, 79, 373. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Structural Equation Modeling Basics. In Multivariate Data Analysis; Pearson Education: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2009; pp. 1–35. [Google Scholar]

- Buelga, S.; Iranzo, B.; Postigo, J.; Carrascosa, L.; Ortega Barón, J. Parental Communication and Feelings of Affiliation in Adolescent Aggressors and Victims of Cyberbullying. Soc. Sci. 2018, 8, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Clements-Nolle, K.; Waddington, R. Adverse childhood experiences and psychological distress in juvenile offenders: The protective influence of resilience and youth assets. J. Adolesc. Health 2019, 64, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalski, R.M.; Limber, S.P. Psychological, physical, and academic correlates of cyberbullying and traditional bullying. J. Adolesc. Health 2013, 53, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iranzo, B.; Buelga, S.; Cava, M.J.; Ortega-Barón, J. Cyberbullying, psychosocial adjustment, and suicidal ideation in adolescence. Psychosoc. Interv. 2019, 25, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Droogenbroeck, F.; Spruyt, B.; Keppens, G. Gender differences in mental health problems among adolescents and the role of social support: Results from the Belgian health interview surveys 2008 and 2013. BMC Psychiatry 2018, 18, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hughes, E.K.; Gullone, E. Internalizing symptoms and disorders in families of adolescents: A review of family systems literature. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2008, 28, 92–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schulz, S.; Nelemans, S.A.; Oldehinkel, A.J.; Meeus, W.; Branje, S. Examining intergenerational transmission of psychopathology: Associations between parental and adolescent internalizing and externalizing symptoms across adolescence. Dev. Psychol. 2021, 57, 269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Musitu, G.; Estévez, E.; Emler, N. Adjustment problems in the family and school contexts, attitude towards authority, and violent behavior at school in adolescence. Adolescence 2007, 42, 779–794. [Google Scholar]

- Mazzone, A.; Camodeca, M. Bullying and Moral Disengagement in Early Adolescence: Do Personality and Family Functioning Matter? J. Child Fam. Stud. 2019, 28, 2120–2130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuñez-Fadda, S.M.; Castro-Castañeda, R.; Vargas-Jiménez, E.; Musitu-Ochoa, G.; Callejas-Jerónimo, J.E. Victimization among Mexican Adolescents: Psychosocial Differences from an Ecological Approach. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez, T.I.; Estévez, E.; Murgui, S. Ambiente comunitario y actitud hacia la autoridad: Relaciones con la calidad de las relaciones familiares y con la agresión hacia los iguales en adolescentes. An. Psicol. 2014, 30, 1086–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | |||||||

| 0.130 ** | 1 | ||||||

| 0.149 ** | 0.175 ** | 1 | |||||

| 0.222 ** | 0.429 ** | 0.396 ** | 1 | ||||

| 0.150 ** | 0.141 ** | 0.647 ** | 0.279 ** | 1 | |||

| 0.207 ** | 0.357 ** | 0.314 ** | 0.676 ** | 0.439 ** | 1 | ||

| 0.182 ** | 0.343 ** | 0.157 ** | 0.334 ** | 0.127 ** | 0.244 ** | 1 | |

| 0.145 ** | 0.252 ** | 0.099 ** | 0.233 ** | 0.132 ** | 0.296 ** | 0.691 ** | 1 |

| M/SD | 1.58/0.068 | 2.04/0.85 | 1.06/0.27 | 1.56/0.66 | 1.07/0.30 | 1.45/0.64 | 2.02/0.78 | 1.93/0.79 |

| Variables | Factorial Loading General Model |

|---|---|

| Offensive Family Communication | |

| Mother’s Offensive Communication | 5.195 (0.112) *** |

| Father’s Offensive Communication | 3.998 (0.100) *** |

| Psychological Distress | |

| Part 1 of Psychological Distress | 2.911 (0.040) *** |

| Part 2 of Psychological Distress | 2.469 (0.34) *** |

| Part 3 of Psychological Distress | 2.469 (0.034) *** |

| Positive Attitude Towards the Transgression of Rules | |

| Item 4 | 0.440 (0.015) *** |

| Item 8 | 0.649 (0.015) *** |

| Item 9 | 0.725 (0.014) *** |

| Item 10 | 0.608 (0.015) *** |

| Child-to-Parent Violence | |

| Child-to-parent Violence Mother | 2.631 (0.092) *** |

| Child-to-parent Violence Father | 2.263 (0.092) *** |

| β | Standard Errors (s) | p | 95% CI | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LCL | UCL | ||||

| Indirect effects | |||||

| OFC → PD → CPV | 0.131 | 0.009 | <0.001 | 0.113 | 0.150 |

| OFC → PATTR → CPV | 0.052 | 0.006 | <0.001 | 0.041 | 0.063 |

| Direct effects | |||||

| OFC → CPV | 0.173 | 0.019 | <0.001 | 0.136 | 0.210 |

| Total effects | |||||

| OFC → CPV | 0.357 | 0.019 | <0.001 | 0.306 | 0.408 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Romero-Abrio, A.; Musitu-Ochoa, G.; Sánchez-Sosa, J.C.; Callejas-Jerónimo, J.E. Psychosocial Adjustment Factors Associated with Child–Parent Violence: The Role of Family Communication and a Transgressive Attitude in Adolescence. Healthcare 2024, 12, 705. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12070705

Romero-Abrio A, Musitu-Ochoa G, Sánchez-Sosa JC, Callejas-Jerónimo JE. Psychosocial Adjustment Factors Associated with Child–Parent Violence: The Role of Family Communication and a Transgressive Attitude in Adolescence. Healthcare. 2024; 12(7):705. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12070705

Chicago/Turabian StyleRomero-Abrio, Ana, Gonzalo Musitu-Ochoa, Juan Carlos Sánchez-Sosa, and Juan Evaristo Callejas-Jerónimo. 2024. "Psychosocial Adjustment Factors Associated with Child–Parent Violence: The Role of Family Communication and a Transgressive Attitude in Adolescence" Healthcare 12, no. 7: 705. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12070705

APA StyleRomero-Abrio, A., Musitu-Ochoa, G., Sánchez-Sosa, J. C., & Callejas-Jerónimo, J. E. (2024). Psychosocial Adjustment Factors Associated with Child–Parent Violence: The Role of Family Communication and a Transgressive Attitude in Adolescence. Healthcare, 12(7), 705. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12070705