An International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health Model-Based Analysis of Suicidal Ideation among 9920 Community-Dwelling Korean Older Adults

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

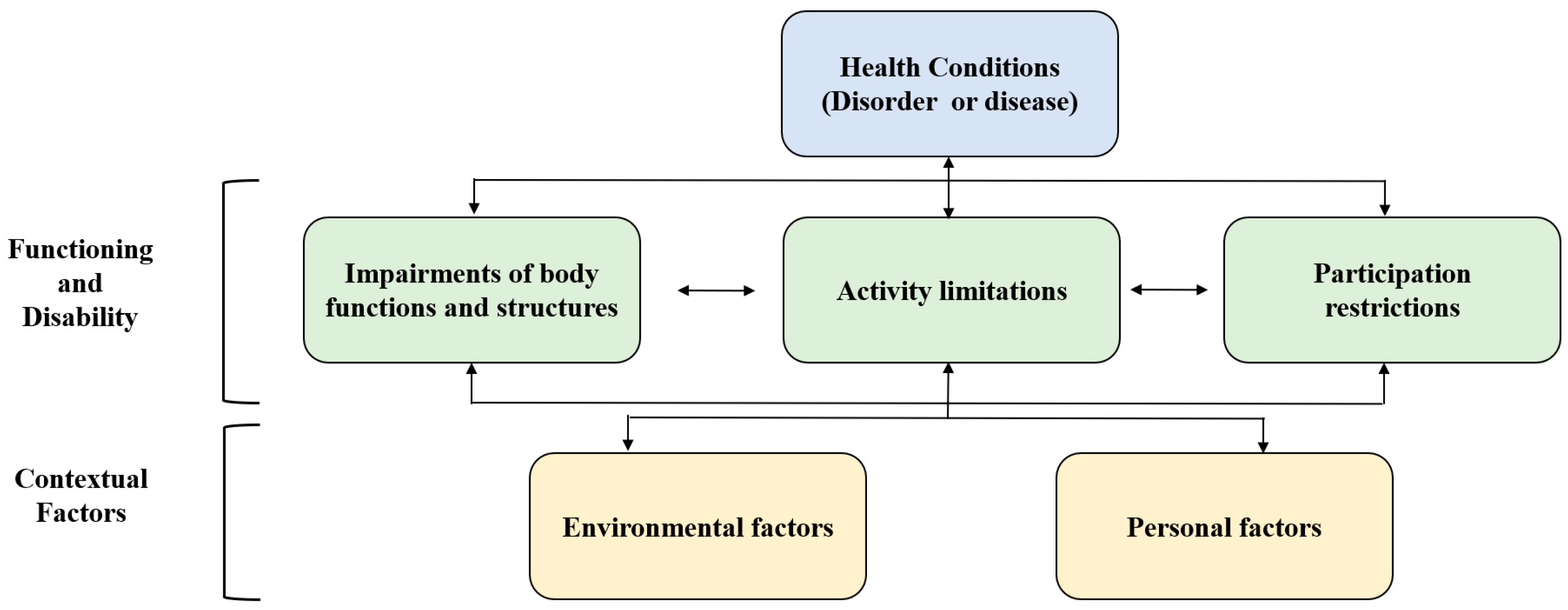

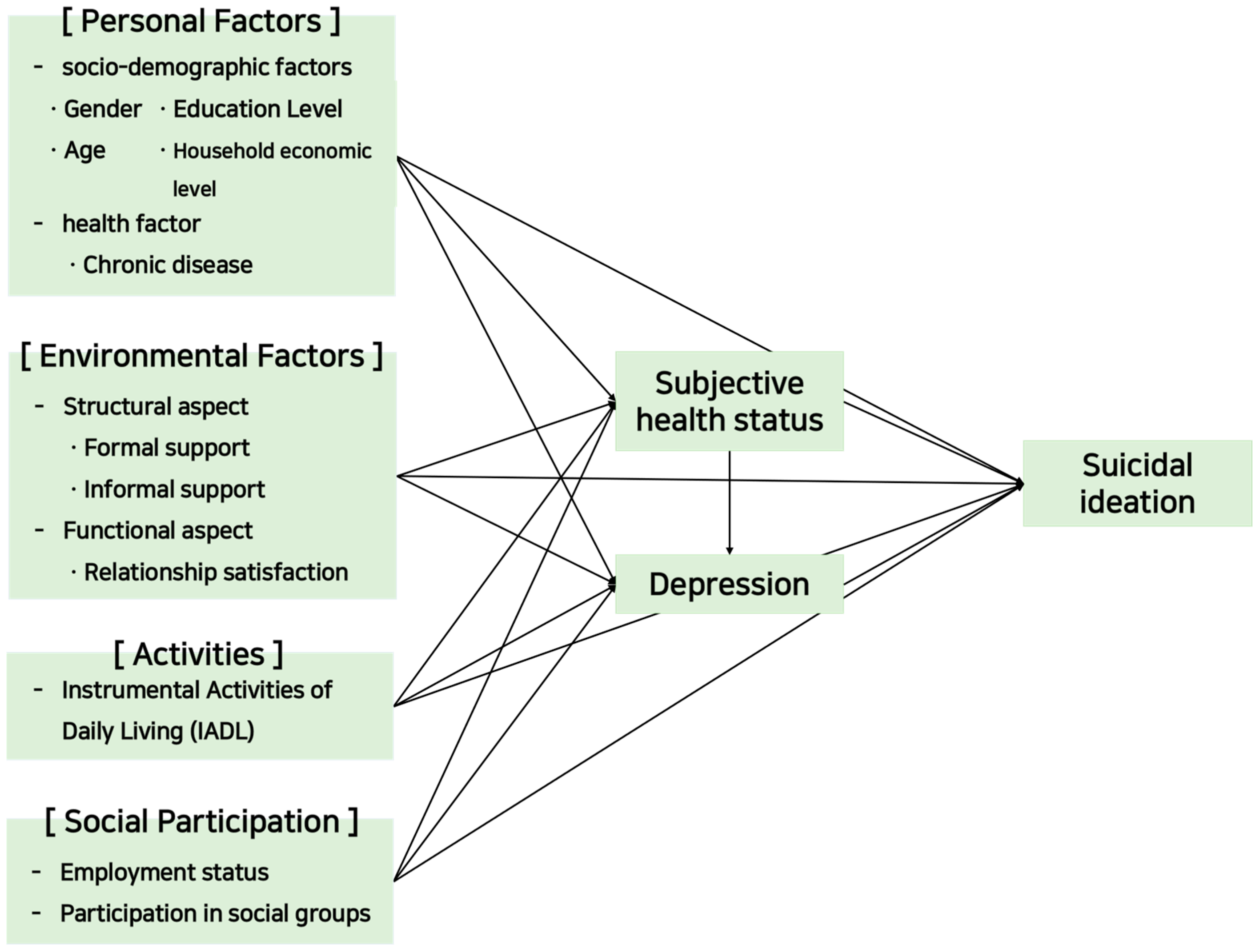

2.1. Research Model

2.2. Data Source

2.3. Measurement and Definition of Variables

3. Results

3.1. General Characteristics

3.2. Predictive Model Validation: Fitness of the Predictive Model

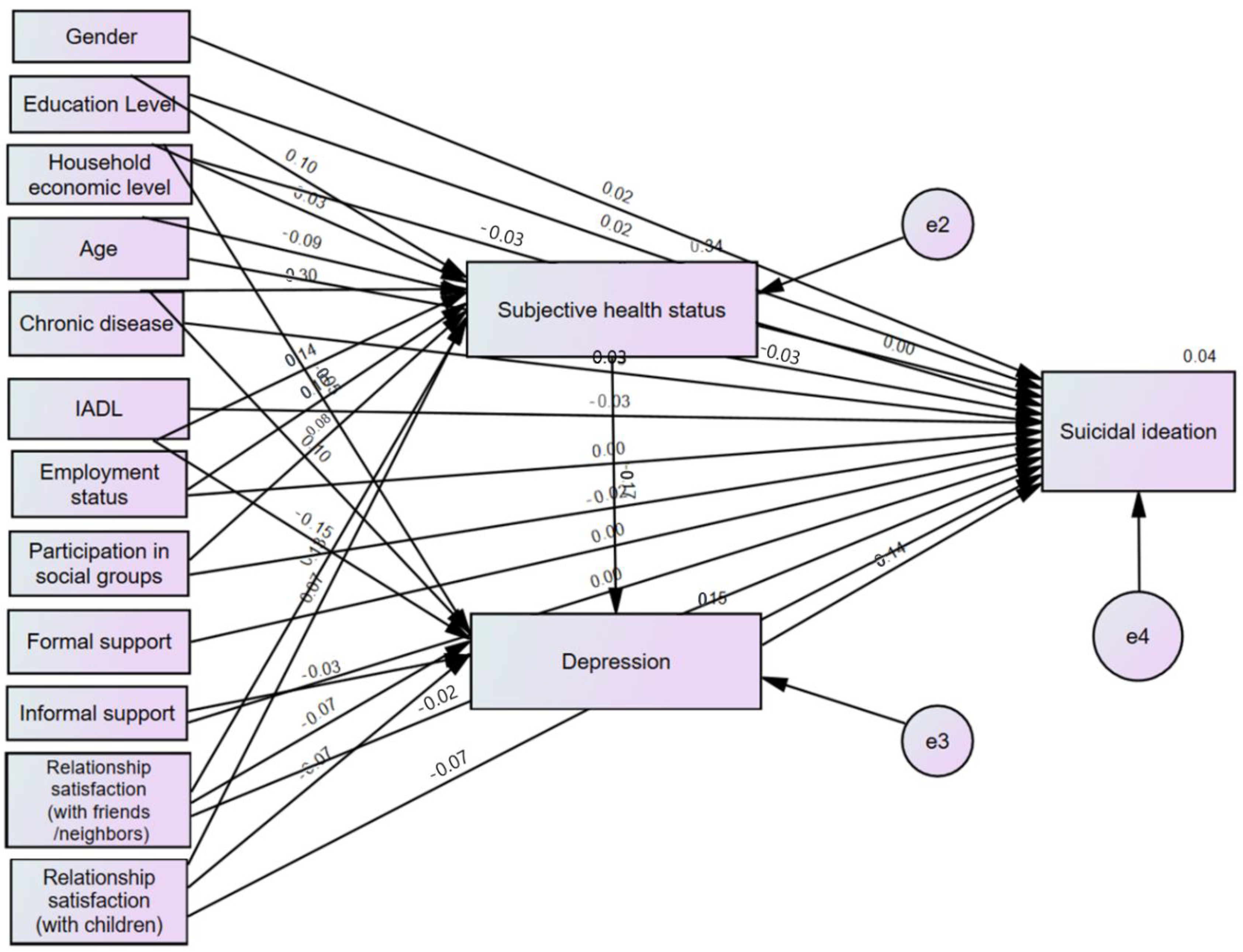

3.3. Estimation of Path Coefficients of the Predictive Model

3.4. Effect Analysis of the Predictive Model

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hong, S.B. Restriction on SSRI (Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitor) Antidepressant Prescription and Effort to Improve. Korean J. Fam. Pract. 2022, 12, 212–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, E. The influences of mental health problem on suicide-related behaviors among adolescents: Based on Korean Youth Health Behavior Survey. J. Korean Acad. Soc. Nurs. Educ. 2023, 29, 98–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Health and Welfare. White Paper on Suicide Prevention in 2022. Available online: https://www.korea.kr/archive/expDocView.do?docId=40007 (accessed on 9 September 2023).

- López-Goñi, J.J.; Fernández-Montalvo, J.; Arteaga, A.; Haro, B. Suicidal attempts among patients with substance use disorders who present with suicidal ideation. Addict. Behav. 2019, 89, 5–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sher, L.; Oquendo, M.A. Suicide: An overview for clinicians. Med. Clin. 2023, 107, 119–130. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.W.; Bae, K.Y.; Kim, J.M.; Kim, S.Y.; Yoo, J.A.; Yang, S.J.; Shin, I.S.; Park, J.H.; Kim, S.H.; Yoon, J.S. Psychosocial correlates of attempted suicide and attitudes toward suicide. J. Korean Neuropsychiatr. Assoc. 2010, 49, 367–373. [Google Scholar]

- Ko, J.; Harrington, D. Factor structure and validity of the K6 scale for adults with suicidal ideation. J. Soc. Soc. Work Res. 2016, 7, 43–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beghi, M.; Butera, E.; Cerri, C.G.; Cornaggia, C.M.; Febbo, F.; Mollica, A.; Berardino, G.; Piscitelli, D.; Resta, E.; Logroscino, G.; et al. Suicidal behaviour in older age: A systematic review of risk factors associated to suicide attempts and completed suicides. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2021, 127, 193–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alves, V.D.M.; Maia, A.C.C.; Nardi, A.E. Suicide among elderly: A systematic review. MedicalExpress 2014, 1, 9–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Rodrigues, V.; Sanchez-Carro, Y.; Lagunas, L.N.; Rico-Uribe, L.A.; Pemau, A.; Diaz-Carracedo, P.; Diaz-Marsa, M.; Hervas, G.; de la Torre-Luque, A. Risk factors for suicidal behaviour in late-life depression: A systematic review. World J. Psychiatry 2022, 12, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eom, T.W. Elderly suicide and its related factors: Focused on the role of social support and mastery in the effects of hopelessness and depression on suicidal ideation. Korean J. Soc. Welf. 2007, 59, 355–379. [Google Scholar]

- Cabello, M.; Miret, M.; Ayuso-Mateos, J.; Caballero, F.; Chatterji, S.; Tobiasz–Adamczyk, B.; Haro, J.; Koskinen, S.; Leonardi, M.; Borges, G. Cross-national prevalence and factors associated with suicide ideation and attempts in older and young-and-middle age people. Aging Ment. Health 2020, 24, 1625–1636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.h.; Kwon, J. The impact of health-related quality of life on suicidal ideation and suicide attempts among Korean older adults. J. Gerontol. Nurs. 2012, 38, 48–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health: ICF; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang, W.; Lee, J.h.; Ahn, S.; Guak, J.; Oh, J.; Park, I.; Cho, M. Exploring the Impact of Appetite Alteration on Self-Management and Malnutrition in Maintenance Hemodialysis Patients: A Mixed Methods Research Using the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) Framework. Clin. Nutr. Res. 2023, 12, 126–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rautiainen, I.; Parviainen, L.; Jakoaho, V.; Äyrämö, S.; Kauppi, J.-P. Utilizing the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) in forming a personal health index. arXiv 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostanjsek, N. Use of The International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) as a conceptual framework and common language for disability statistics and health information systems. BMC Public Health 2011, 11, S3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bufka, L.F.; Stewart, D.; Stark, S. The International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) is emerging as the principal framework for the description of health and health related status. Can. J. Occup. Ther. 2008, 75, 134. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ministry of Health and Welfare, Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs. A Survey of the Elderly in 2020. Available online: https://repository.kihasa.re.kr/handle/201002/38157 (accessed on 9 September 2023).

- Been, S.; Byeon, H. Predicting Depression in Older Adults after the COVID-19 Pandemic Using ICF Model. Healthcare 2023, 11, 1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bae, J.N.; Cho, M.J. Development of the Korean version of the Geriatric Depression Scale and its short form among elderly psychiatric patients. J. Psychosom. Res. 2004, 57, 297–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Won, C.W.; Rho, Y.G.; SunWoo, D.; Lee, Y.S. The validity and reliability of Korean Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (K-IADL) scale. J. Korean Geriatr. Soc. 2002, 6, 273–280. [Google Scholar]

- Park, Y.K.; Suh, S.R. A predictive model of instrumental activities of daily living in community-dwelling elderly based on ICF model. J. Korea Contents Assoc. 2018, 18, 113–123. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, Y.J.; Hwang, Y.; Lee, C. Effects of Depression, Suicidal Ideation, and Gratitude on Flourishing of High School Students: A Moderated Mediation Model of Growth Mindset. Psychol. Educ. 2022, 2022, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, X.; Yang, G.-Y.; Feng, Z. Impulsiveness indirectly affects suicidal ideation through depression and simultaneously moderates the indirect effect: A moderated mediation path model. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 913680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, J.; Chen, X.; Dai, Z.-D.; Huang, Y.; Xiao, W.; Wang, H.; Si, M.; Wu, Y.-J.; Zhang, L.; Jing, S.; et al. HIV-related stigma, depression and suicidal ideation among HIV-positive MSM in China: A moderated mediation model. BMC Public Health 2023, 23, 2117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, J.R.; Ballard, E.D.; Galiano, C.S.; Nugent, A.C.; Zarate, C.A., Jr. Magnetoencephalographic correlates of suicidal ideation in major depression. Biol. Psychiatry Cogn. Neurosci. Neuroimaging 2020, 5, 354–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, H.G.; Sim, J.M.; Lee, K.C. An empirical analysis of effects of depression on suicidal ideation of Korean adults: Emphasis on 2008~2012 KNHANES dataset. J. Korea Contents Assoc. 2015, 15, 264–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmaal, L.; van Harmelen, A.L.; Chatzi, V.; Lippard, E.T.; Toenders, Y.J.; Averill, L.A.; Mazure, C.M.; Blumberg, H.P. Imaging suicidal thoughts and behaviors: A comprehensive review of 2 decades of neuroimaging studies. Mol. Psychiatry 2020, 25, 408–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, K.; Kim, S.W.; Myung, W.; Han, C.E.; Fava, M.; Mischoulon, D.; Papakostas, G.I.; Seo, S.W.; Cho, H.; Seong, J.-K.; et al. Reduced orbitofrontal-thalamic functional connectivity related to suicidal ideation in patients with major depressive disorder. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 15772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Won, M.; Choi, E.J.; Ko, E.; Um, Y.J.; Choi, Y. The mediating effect of life satisfaction and the moderated mediating effect of social support on the relationship between depression and suicidal behavior among older adults. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2021, 36, 1732–1738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, B.; Kihl, T. Suicidal ideation associated with depression and social support: A survey-based analysis of older adults in South Korea. BMC Psychiatry 2021, 21, 409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, Y.O.; Yoon, H.S.; Hwang, J.S. The Effect of Negative Self image on Self Neglect of Living alone Elderly with Low income: Focusing on the mediation effect of depression. Korean J. Soc. Welf. Res. 2016, 50, 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Y.R.; Park, C.S.; Nam, H.J. Comparative, integrated study on emotional support, physical support, socio-economic factors related with suicidal ideation of 75 or older seniors: Using the 2017 national survey of elderly. J. Korea Converg. Soc. 2019, 10, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueiredo, A.E.B.; Silva, R.M.D.; Vieira, L.J.E.S.; Mangas, R.M.D.N.; Sousa, G.S.D.; Freitas, J.S.; Conte, M.; Sougey, E.B. Is it possible to overcome suicidal ideation and suicide attempts? A study of the elderly. Cien. Saude Colet. 2015, 20, 1711–1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lutz, J.; Fiske, A. Functional disability and suicidal behavior in middle-aged and older adults: A systematic critical review. J. Affect. Disord. 2018, 227, 260–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sim, H.S.; Lee, S.G.; Kim, T.H. Physical Functioning, Depressive Symptoms, and Suicidal Ideation among Older Korean Adults. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 8781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becattini-Oliveira, A.C.; Câmara, L.; Dutra, D.F.; Sigrist, A.A.F.; Charchat-Fichman, H. Performance-based instrument to assess functional capacity in community-dwelling older adults. Dement. Neuropsychol. 2019, 13, 386–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Femia, E.E.; Zarit, S.H.; Johansson, B. The disablement process in very late life: A study of the oldest-old in Sweden. J. Gerontol. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2001, 56, P12–P23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Mehrabi, F.; Béland, F. Frailty as a moderator of the relationship between social isolation and health outcomes in community-dwelling older adults. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Classification | Variables | Suicidal Ideation | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (n = 187) | No (n = 9733) | ||||

| n | % | n | % | ||

| Impairments of body functions and structures | Subjective health status: | ||||

| Poor | 74 | 39.6 | 1786 | 18.3 | |

| Average | 61 | 32.6 | 3059 | 31.4 | |

| Good | 52 | 27.8 | 4888 | 50.2 | |

| Depression: | |||||

| No depression | 57 | 49.5 | 8540 | 87.7 | |

| Depression | 100 | 53.5 | 1193 | 12.3 | |

| Personal Factors: socio-demographic factors | Gender: | ||||

| Male | 54 | 28.9 | 3917 | 40.2 | |

| Female | 133 | 71.1 | 5816 | 59.8 | |

| Age: | |||||

| 65–74 years old | 104 | 55.6 | 5873 | 60.3 | |

| 75–84 years old | 78 | 41.7 | 3255 | 33.4 | |

| ≥85 years old | 5 | 2.7 | 605 | 6.2 | |

| Education Level: | |||||

| Elementary school graduation or below | 90 | 48.1 | 4341 | 44.6 | |

| Middle school graduation | 52 | 27.8 | 2278 | 23.4 | |

| High school graduation | 38 | 20.3 | 2616 | 26.9 | |

| College graduation or above | 7 | 3.7 | 498 | 5.1 | |

| Household economic level: | |||||

| National basic livelihood security recipient | 37 | 19.8 | 688 | 7.1 | |

| National basic livelihood security non-recipient | 150 | 80.2 | 9045 | 92.9 | |

| Personal Factors: health factor | Chronic disease: | ||||

| ≤1 | 47 | 25.1 | 4553 | 46.8 | |

| 2–4 | 111 | 59.4 | 4725 | 48.5 | |

| ≥5 | 29 | 15.5 | 455 | 4.7 | |

| Environmental Factors | Formal support | ||||

| (used a senior citizen center or senior welfare service center in the community in the past year): | |||||

| Used | 51 | 27.3 | 2907 | 29.9 | |

| Never used | 136 | 72.7 | 6826 | 70.1 | |

| Informal support | |||||

| (frequency of meeting an acquaintance in the past year): | |||||

| ≥2 times a year | 42 | 22.5 | 1644 | 16.9 | |

| 1–2 times every 3 months | 49 | 26.2 | 2749 | 28.2 | |

| 1–2 times a month | 68 | 36.4 | 3761 | 38.6 | |

| Once a week | 18 | 9.6 | 1016 | 10.4 | |

| Everyday | 10 | 5.3 | 563 | 5.8 | |

| Relationship satisfaction | |||||

| (with children): | |||||

| Dissatisfied | 38 | 20.3 | 343 | 3.5 | |

| Not satisfied or dissatisfied | 53 | 28.3 | 2063 | 21.2 | |

| Satisfied | 96 | 51.3 | 7327 | 75.3 | |

| Relationship satisfaction | |||||

| (with friends/neighbors): | |||||

| Dissatisfied | 46 | 24.6 | 566 | 5.8 | |

| Not satisfied or dissatisfied | 64 | 34.2 | 3316 | 34.1 | |

| Satisfied | 77 | 41.2 | 5851 | 60.1 | |

| Activities | Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADL): | ||||

| ≤25 points | 28 | 15 | 376 | 3.9 | |

| ≥26 points | 159 | 85 | 9357 | 96.1 | |

| Social Participation | Employment status: | ||||

| No | 140 | 74.9 | 6166 | 63.4 | |

| Yes | 47 | 25.1 | 3567 | 36.6 | |

| Participation in social groups: | |||||

| No | 137 | 73.3 | 5642 | 58 | |

| Yes | 50 | 26.7 | 4091 | 42 | |

| CMIN/DF | GFI | AGFI | CFI | TLI | RMSEA | SRMR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2.811 | 1.00 | 0.995 | 0.999 | 0.989 | 0.014 | 0.004 |

| Path | β | S.E. | C.R. | SMC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subjective Health Status | ← Education level | 0.104 | 0.007 | 11.299 *** | 0.338 |

| ← Household economic level | 0.033 | 0.025 | 3.918 *** | ||

| ← Age | −0.094 | 0.012 | −9.98 *** | ||

| ← Chronic disease | −0.305 | 0.011 | −35.411 *** | ||

| ← IADL | 0.143 | 0.033 | 16.634 *** | ||

| ← Employment status | 0.102 | 0.014 | 11.884 *** | ||

| ← Informal support | 0.083 | 0.014 | 9.149 *** | ||

| ← Relationship satisfaction (with friends/neighbors) | 0.131 | 0.012 | 14.234 *** | ||

| ← Relationship satisfaction (with children) | 0.067 | 0.013 | 7.565 *** | ||

| Depression | ← Subjective Health Status | −0.171 | 0.005 | −15.688 *** | 0.146 |

| ← Household economic level | −0.053 | 0.012 | −5.543 *** | ||

| ← Chronic disease | 0.101 | 0.006 | 9.789 *** | ||

| ← IADL | −0.149 | 0.017 | −15.187 *** | ||

| ← Informal support | −0.031 | 0.003 | −3.31 *** | ||

| ← Relationship satisfaction (with friends/neighbors) | −0.068 | 0.006 | −6.566 *** | ||

| ← Relationship satisfaction (with children) | −0.074 | 0.006 | −7.359 *** | ||

| Suicidal ideation | ← Gender | 0.025 | 0.003 | 2.354 * | 0.039 |

| ← Education level | 0.023 | 0.002 | 1.968 * | ||

| ← Household economic level | −0.034 | 0.005 | −3.401 *** | ||

| ← Age | −0.03 | 0.003 | −2.616 ** | ||

| ← IADL | −0.029 | 0.007 | −2.707 ** | ||

| ← Employment status | −0.003 | 0.003 | −0.325 | ||

| ← Participation in social groups | −0.016 | 0.003 | −1.428 | ||

| ← Employment status | 0.001 | 0.003 | 0.114 | ||

| ← Informal support | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.138 | ||

| ← Relationship satisfaction (with friends/neighbors) | −0.021 | 0.003 | −1.846 | ||

| ← Relationship satisfaction (with children) | −0.066 | 0.003 | −6.133 *** | ||

| ← Subjective Health Status | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.144 | ||

| ← Depression | 0.136 | 0.004 | 12.767 *** | ||

| ← Chronic disease | 0.028 | 0.003 | 2.504 * | ||

| Path | Total Effect | Direct Effect | Indirect Effect | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subjective Health Status | ← Education level | 0.104 *** | 0.104 *** | − |

| ← Household economic level | 0.033 *** | 0.033 *** | − | |

| ← Age | −0.094 *** | −0.094 *** | − | |

| ← Chronic disease | −0.305 *** | −0.305 *** | − | |

| ← IADL | 0.143 *** | 0.143 *** | − | |

| ← Employment status | 0.102 *** | 0.102 *** | − | |

| ← Informal support | <0.001 | <0.001 | − | |

| ←Relationship satisfaction (with friends/neighbors) | 0.131 *** | 0.131 *** | − | |

| ← Relationship satisfaction (with children) | 0.067 *** | 0.067 *** | − | |

| Depression | ← Subjective Health Status | −0.171 *** | −0.171 *** | − |

| ← Household economic level | −0.058 *** | −0.053 *** | −0.006 *** | |

| ← Chronic disease | 0.154 *** | 0.101 *** | 0.052 *** | |

| ← IADL | −0.174 *** | −0.149 *** | −0.023 *** | |

| ← Informal support | −0.031 ** | −0.031 ** | −0.004 | |

| ←Relationship satisfaction (with friends/neighbors) | −0.091 *** | −0.068 *** | −0.022 *** | |

| ← Relationship satisfaction (with children) | −0.086 *** | −0.074 *** | −0.011 *** | |

| Suicidal ideation | ← Gender | 0.025 ** | 0.025 ** | − |

| ← Education level | 0.021 | 0.023 * | −0.002 | |

| ← Household economic level | −0.042 ** | −0.034 ** | −0.008 *** | |

| ← Age | −0.028 ** | −0.03 ** | 0.002 | |

| ← IADL | −0.052 ** | −0.029 ** | −0.023 *** | |

| ← Employment status | −0.006 | −0.003 *** | −0.002 | |

| ← Participation in social groups | −0.018 | −0.016 | −0.002 | |

| ← Employment status | 0.001 | 0.001 | <0.001 | |

| ← Informal support | −0.003 | 0.001 | −0.004 ** | |

| ← Relationship satisfaction (with friends/neighbors) | −0.033 ** | −0.021 | −0.012 *** | |

| ← Relationship satisfaction (with children) | −0.078 *** | −0.066 *** | −0.012 *** | |

| ← Subjective Health Status | −0.022 | 0.002 | −0.023 *** | |

| ← Depression | 0.136 *** | 0.136 *** | <0.001 | |

| ← Chronic disease | 0.048 *** | 0.028 ** | 0.02 *** | |

| Path | Estimate |

|---|---|

| Subjective health status | |

| Education level → Subjective Health Status → Suicidal ideation | <0.001 |

| Household economic level → Subjective Health Status → Suicidal ideation | <0.001 |

| Age → Subjective Health Status → Suicidal ideation | <0.001 |

| Chronic disease → Subjective Health Status → Suicidal ideation | −0.001 |

| IADL → Subjective Health Status → Suicidal ideation | <0.001 |

| Employment status → Subjective Health Status → Suicidal ideation | <0.001 |

| Participation in social groups → Subjective Health Status → Suicidal ideation | <0.001 |

| Relationship satisfaction (with friends/neighbors) → Subjective Health Status → Suicidal ideation | <0.001 |

| Relationship satisfaction (with children) → Subjective Health Status → Suicidal ideation | <0.001 |

| Depression | |

| Household economic level → Depression → Suicidal ideation | −0.007 *** |

| Chronic disease → Depression → Suicidal ideation | 0.014 *** |

| IADL → Depression → Suicidal ideation | −0.02 *** |

| Informal support → Depression → Suicidal ideation | −0.004 *** |

| Relationship satisfaction (with friends/neighbors) → Depression → Suicidal ideation | −0.009 *** |

| Relationship satisfaction (with children) → Depression → Suicidal ideation | −0.001 *** |

| Subjective health status → Depression | |

| Education level → Subjective Health Status → Depression → Suicidal ideation | −0.002 *** |

| Household economic level → Subjective Health Status → Depression → Suicidal ideation | −0.001 *** |

| Age → Subjective Health Status → Depression → Suicidal ideation | 0.002 *** |

| Chronic disease → Subjective Health Status → Depression → Suicidal ideation | 0.007 *** |

| IADL → Subjective Health Status → Depression → Suicidal ideation | −0.003 *** |

| Employment status → Subjective Health Status → Depression → Suicidal ideation | −0.002 *** |

| Participation in social groups → Subjective Health Status → Depression → Suicidal ideation | −0.002 *** |

| Relationship satisfaction (with friends/neighbors) → Subjective Health Status → Depression → Suicidal ideation | −0.003 *** |

| Relationship satisfaction (with children) → Subjective Health Status → Depression → Suicidal ideation | −0.002 *** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Byeon, H. An International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health Model-Based Analysis of Suicidal Ideation among 9920 Community-Dwelling Korean Older Adults. Healthcare 2024, 12, 538. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12050538

Byeon H. An International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health Model-Based Analysis of Suicidal Ideation among 9920 Community-Dwelling Korean Older Adults. Healthcare. 2024; 12(5):538. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12050538

Chicago/Turabian StyleByeon, Haewon. 2024. "An International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health Model-Based Analysis of Suicidal Ideation among 9920 Community-Dwelling Korean Older Adults" Healthcare 12, no. 5: 538. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12050538

APA StyleByeon, H. (2024). An International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health Model-Based Analysis of Suicidal Ideation among 9920 Community-Dwelling Korean Older Adults. Healthcare, 12(5), 538. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12050538