Family Nursing Care during the Transition to Parenthood: A Scoping Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Families in Transition to Parenthood

1.2. Family Nursing and the Transition to Parenthood

2. Methods

2.1. Review Questions

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Types of Sources

2.4. Search Strategy

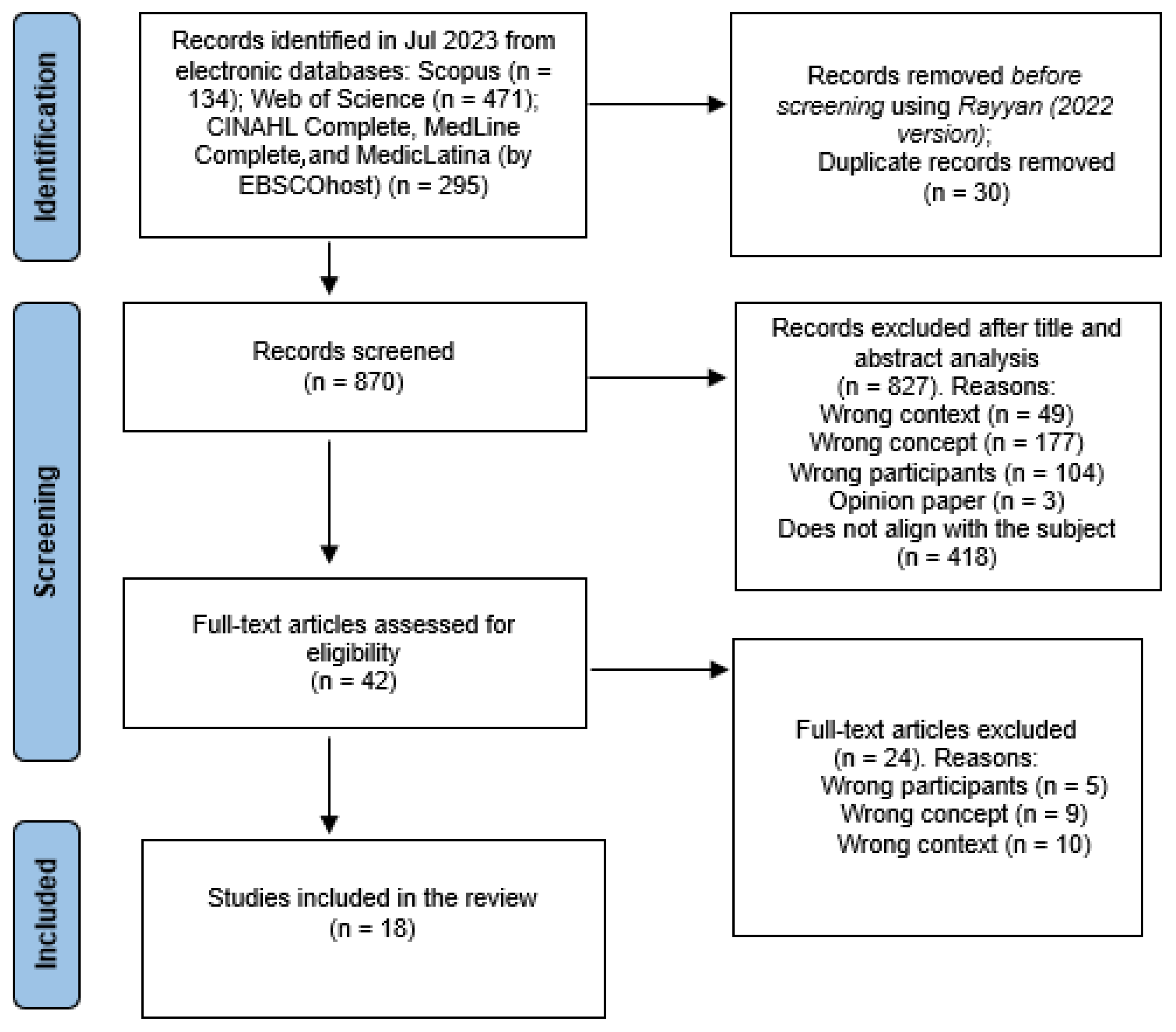

2.5. Study/Source of Evidence Selection

2.6. Data Extraction

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Transition to Parenthood

4.2. Families’ Characteristics

4.3. The Role of Family Nurses in Facilitating the Transition to Parenthood and the Adaption to the New Family Member

4.3.1. Family-Centered Approaches

4.3.2. Well-Being Promotion

4.3.3. Promoting Breastfeeding

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions and Implications to Practice

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Population (P) | Concept (C) | Context (C) |

|---|---|---|

| Pregnancy | Education | Family nursing |

| New family | Adaptation | Primary healthcare |

| Parents | Transition | |

| Parenthood | Family | |

| Newborn | Family life cycle | |

| Family dynamic | ||

| Family relation |

| Database | Search Terms/Boolean Phrase | Results (n) |

|---|---|---|

| Scopus | (TITLE-ABS-KEY (parenthood OR “new family” OR pregnancy OR parents) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY (education OR adaptation OR transition OR “family life cycle”) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY (“family nursing” OR “primary health care”) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY (“family dynamic” OR family AND relations)) AND PUBYEAR > 2016 AND PUBYEAR < 2024 AND (LIMIT-TO (DOCTYPE, “ar”) OR LIMIT-TO (DOCTYPE, “re”)) AND (LIMIT-TO (LANGUAGE, “Portuguese”) OR LIMIT-TO (LANGUAGE, “Spanish”) OR LIMIT-TO (LANGUAGE, “English”)) AND (LIMIT-TO (SRCTYPE, “j”)) AND (LIMIT-TO (PUBSTAGE, “final”)) | n = 134 |

| CINAHL Complete, MedLine Complete, and MedicLatina (by EBSCOhost) | AB (newborn OR parenthood OR pregnancy OR parents) AND AB (family nursing OR primary health care) AND AB (education Or preparation) Limiters – Scientific Magazines (Peer Reviewed); Publication Date: 20170101-20231231; Expanders: Apply to equivalent subjects; Restrict by language: Spanish; Restrict by language: Portuguese; Restrict by language: English; Search modes: Boolean/Phrase 150 duplicates in the different databases were excluded, exporting 295 articles in total | n = 295 |

| Web of Science | Results for TI = (parenthood OR pregnancy OR parents AND education OR adaptation OR transition AND “family nursing” OR “primary health care” AND “family dynamic” OR “family relations”) and Highly Cited Papers and 2024 or 2023 or 2022 or 2021 or 2020 or 2019 or 2018 or 2017 (Publication Years) and Review Article or Article (Document Types) and Highly Cited Papers and Article or Review Article (Document Types) | n = 471 |

| Total n = 900 |

Appendix B

| Authors, Year, Country | Title | Purpose | Methods and Participants | Main Implications for Family Nursing | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agu, A.P.; Akamike, I.C.; Okedo-Alex, I.N.; Umeokonkwo, A.A.; Ogbonna-Igwenyi, C.O.; Madumere, O.D; Keke, C.O. (2022) [31] Nigeria. | Predictors of knowledge and practice of newborn care among post-natal mothers attending immunization clinics in Southeast Nigeria | To assess the knowledge, practice-associated factors, and predictors of essential newborn care among post-natal mothers. | Cross-sectional study. The population included two primary healthcare centers in Southeast Nigeria, with post-natal mothers who attended immunization clinics. | Family support is crucial during the transition to parenthood. Factors like marital status, age, residency, number of previous children, and the level of knowledge about newborn care should be taken into account as potential predictors of parenting practices. | The practice was self-reported and no observation of these mothers was performed. The generalizability of the findings may be limited. Women’s responses may have been subject to recall bias. |

| Alobaysi, H.; Jahan, S. (2022) [35] Saudi Arabia | Infant care practices among mothers attending well-baby clinics at primary healthcare centers in Unaizah City. | To determine practices regarding infant care and to explore the association of these practices with mothers’ demographic data. | Cross-sectional study using a self-administrated questionnaires. A total of 200 mothers attending well-baby clinics in primary healthcare centers (PHCCs) in Unaizah city, Saudi Arabia. | It is important to address infant immunization, ensure timely weaning, supervise the use of formula milk in hospitals, advocate for appropriate infant sleep positions, regulate the use of pacifiers, and strengthen health education initiatives for mothers, to enhance infant care practices. | Social desirability bias cannot be ruled out. This study was carried out in a single city, restricting the applicability of the findings. |

| Andrade, F.M.R.; Simões Figueiredo, A.; Capelas, M.L.; Charepe, Z.; Deodato, S. (2020) [28] Portugal | Experiences of Homeless Families in Parenthood: A Systematic Review and Synthesis of Qualitative Evidence. | To identify the available data and to develop a framework to address the life experiences of homeless families in parenthood. | Systematic review, considering all the studies that focused on homeless families constituted by adult parents, over 18 years of age, and their children, under 18 years of age. | It is crucial to take into consideration families, fathers, or mothers living in adverse conditions to tailor nursing interventions accordingly. | Self-reported experienced feelings; all works were conducted in temporary or transitional shelters; studies published in other languages that were not included; limited number of databases; and possibility of having excluded other valuable text types. |

| Angelhoff, C.; Askenteg, H.; Wikner, U.; Edéll-Gustafsson, U. (2018) [39] Sweden | “To Cope with Everyday Life, I Need to Sleep”—A Phenomenographic Study Exploring Sleep Loss in Parents of Children with Atopic Dermatitis. | To explore and describe perceptions of sleep in parents of children under <2 years old with AD, consequences of parental sleep loss, and what strategies the parents used to manage sleep loss and to improve sleep. | Qualitative interview study of 12 parents with an inductive and descriptive design. | Nurses should promptly identify sleep deprivation in parents of young children with AD to prevent adverse outcomes affecting overall family well-being. | Small sample. |

| Dlamini, L.P.; Hsu, Y.Y.; Shongwe, M.C.; Wang, S.T.; Gau, M.L. (2023) [40] Taiwan | Maternal Self-Efficacy as a Mediator in the Relationship Between Postpartum Depression and Maternal Role Competence: A Cross-Sectional Survey. | To examine the relationships among postpartum depression, maternal self-efficacy, and maternal role competence. | Cross-sectional design, with 343 postpartum mothers from 3 primary healthcare facilities in Eswatini. | It is imperative to identify and address depressive symptoms during the postpartum period to mitigate the risk of low maternal self-confidence and inadequate caregiving skills. | Potential selection bias; potential recall bias. The cross-sectional nature of the study only infers an association and does not establish a cause-and-effect relationship among the studied variables. |

| Hajipour, M., Soltani, M., Safari-Faramani, R., Khazaei, S., Etemad, K., Rahmann, S., Valadbeigi, T., Yaghoobi, H., Rezaeian, S. (2021) [41] Iran | Maternal Sleep and Related Pregnancy Outcomes: A Multicenter Cross-Sectional Study in 11 Provinces of Iran. | To assess the association between sleep disturbance in pregnancy and maternal and child outcomes. | Multicenter cross-sectional study, conducted on 3675 pregnant women across 11 provinces in Iran in 2018. | In addressing the impact of sleep quality on maternal outcomes, it is essential to plan and implement appropriate interventions within the realm of primary healthcare. | |

| Herval, A.; Dumont, D.P.; Gomes, V.E.; Vargas, A.M.D.; Schaller, B. (2019) [34] Brazil | Health education strategies targeting maternal and child health: A scoping review of educational methodologies. | To identify health education strategies targeting pregnant women to improve results of pregnancy at an urban level. | Scoping review. | Various health education strategies can be employed to enhance maternal and child outcomes. One crucial approach involves sustaining health education strategies beyond childbirth, with a particular emphasis on improving breastfeeding practices. | Most of the studies included were developed in high-income countries; therefore, the results should be carefully analyzed by policy makers from low- and middle-income regions and populations. Some studies did not provide enough information about how often and for how long people were educated. |

| Hickey, G.; McGilloway, S.; Leckey, Y.; Stokes, A. (2018) [30] Ireland | A Universal Early Parenting Education Intervention in Community-Based Primary Care Settings: Development and Installation Challenges. | To provide an overview of the development and setting up of the Parent and Infant (PIN) program and to explore its cost-effectiveness. | Multi-method evaluation; controlled trial evaluation. Total participants: 190 parents. | Creating a welcoming environment for interagency parenting support, especially during the child’s first 1000 days, is crucial. The objective is to engage and empower parents through evidence-based prevention and early intervention. | |

| Hopwood, N.; Clerke, T.; Nguyen, A. (2018) [42] Australia | A pedagogical framework for facilitating parents’ learning in nurse–parent Partnership. | To examine the role of nurses in facilitating parents’ learning in services for families with young children. | Descriptive study. Observational data were collected in home visiting, day-stay, and toddler clinics in 3 Local Health Districts (LHDs). Participants: 19 nurses and 60 parents from 58 different families. | Through observation of various aspects of children and parents, as well as their interactions, nurses can facilitate the transformative process by building on the strengths of parents. | |

| Massi, L.; Hickey, S.; Maidment, S.J.; Roe, Y.; Kildea, S.; Nelson, C.; Kruske, S. (2021) [37] Australia | Improving interagency service integration of the Australian Nurse-Family Partnership Program for First Nations women and babies: a qualitative study. | To explore the barriers and enablers to interagency service integration for the ANFPP in an urban setting. | Qualitative study with 76 participants. | The ANFPP supports women on their journey to motherhood by providing home visits, health education, guidance, and social and emotional support, with a particular focus on those from disadvantaged backgrounds. This approach aims to enhance child outcomes. | Data from women who left the program were included in the analysis. Some participants may have not expressed their views openly. The results may not be transferable to other settings, such as regional and remote locations. |

| Nomaguchi, K; Milkie, M. (2020) [27] Canada | Parenthood and Well-Being: A Decade in Review. | To provide a critical review of scholarship on parenthood and well-being in advanced economies published from 2010 to 2019. | Literature review of scholarly works published as peer-reviewed journal articles, books, and book chapters from 2010 to 2019. | Consideration should be given to the impact of child-rearing stressors. It is crucial to recognize variations in these stressors based on factors such as socioeconomic status, gender, partnership status, and race/ethnicity. Parental well-being should be a focal point in both pre- and postnatal care, emphasizing the importance of providing families with multifaceted social support. | Due to space limitations, this review is highly selective, focusing on significant themes in research from the past decade. |

| Piro, S.S.; Ahmed, H.M. (2020) [32] Iraq | Impacts of antenatal nursing interventions on mothers’ breastfeeding self-efficacy: an experimental study. | To evaluate the role of nursing intervention on mother’s breastfeeding self-efficacy. | Experimental investigation with 130 pregnant women who attended a primary healthcare center. | Effective provision of antenatal breastfeeding education enhances breastfeeding self-efficacy, subsequently fostering increased self-confidence, knowledge, and positive attitudes toward the practice of exclusive breastfeeding. | The study sample is derived from one PHCC; so, findings generalization was not possible. Response bias might have occurred. The results may have been influenced by the personality and environment of the mother. The researcher’s preconceived expectations may have influenced their interaction with participants. |

| Sacks, E.; Freeman, P.A.; Sakyi, K.; Jennings, M.C.; Rassekh, B.M.; Gupta, S.; Perry, H.B. (2017) [38] USA | A comprehensive review of the evidence regarding the effectiveness of community-based primary healthcare in improving maternal, neonatal and child health: 3.Neonatal health findings. | To review the available evidence regarding the effectiveness of community-based primary healthcare (CBPHC) and common components of programs aiming to improve health during the first 28 days of life. | Systematic review of the effectiveness of projects, programs, and field research studies in improving maternal, neonatal, and child health through CBPHC. | CBPHC can significantly enhance neonatal health, particularly in settings with high mortality rates and limited resources. Key strategies include home visitation, education on preventing complications, recognizing alarming signs, providing early treatment or referrals, early immunization, outreach, and involving participatory women’s groups. | Notable geographic bias. Many of the studies were pilot studies rather than large-scale projects. A lack of information on the quality of care and the diverse definitions and measurements used in the studies. |

| Salih, B.B.; Khaleel, M.A. (2022) [36] Iraq | A Study on Pregnant Mothers’ Knowledge and Self-Management Toward Prenatal Care Services in Baghdad City. | To assess pregnant mothers’ knowledge and self-management toward prenatal care services by attending primary healthcare facilities in Baghdad City. | Descriptive cross-sectional study with 206 pregnant women taking prenatal care services in 3 primary healthcare centers of Baghdad City. | In order to reduce complications during and after pregnancy, it is recommended to establish additional and consistent instructions for prenatal care within primary health centers. These instructions should be presented in a clear and easily understandable format. | |

| Savci Bakan, A.; Aktas, B.; Yalcinoz Baysal, H.; Aykut, N. (2023) [43] Turkey | An Investigation of Pregnant Women’s Attitudes Towards Childhood Vaccination and Trust in Health Services. | To investigate pregnant women’s attitudes toward childhood vaccination and trust in health services. | Descriptive study, conducted in a city located in the eastern part of Turkey with 193 volunteer pregnant women. | Ensuring that children receive vaccinations is crucial for their overall health and well-being. Primary care community health nurses play a pivotal role in providing accurate information to parents, as parental education significantly reduces misunderstandings and promotes the vaccination of children. | |

| Shah, R.; Isaia, A.; Schwartz, A.; Atkins, M. (2019) [33] USA | Encouraging Parenting Behaviours that Promote Early Childhood Development Among Caregivers From Low-Income Urban Communities: A Randomized Static Group Comparison Trial of a Primary Care-Based Parenting Program. | To assess if the Sit Down and Play program can be successful in impacting key parenting behaviors that promote early childhood development. | Randomized controlled trial with an ethnically diverse group of predominantly low-income caregivers of children 2–6 months of age. | Through SDP, nurses can actively promote positive parenting behaviors, such as cognitive stimulation, providing learning materials, and enhancing the quality of parent–child verbal interactions. These efforts can contribute to improved developmental outcomes for children. | Small sample size; exclusion of families who did not speak English; recruitment from a single practice; potential recall bias; possible performance bias; and selection bias in allocation to the control versus intervention group. |

| Strobel, N.; Chamberlain, C.; Campbell, S.; Shields, L.; Bainbridge, R.; Adams, C.; Edmond, K.; Marriott, R.; McCalman, J. (2022) [44] Australia | Family-centered interventions for Indigenous early childhood well-being by primary healthcare services. | To evaluate the benefits and harms of family-centered interventions on a range of outcomes of Indigenous children, parents, and families. | Systematic review. | Family-centered care provided by primary healthcare services prioritizes elements such as the environment, communication, education, counseling, and support for families. Its objective is to improve the health and well-being of children, parents, and their families. | The quality of evidence for all outcomes is quite low. |

| Vidaurreta, M.; Lopez-Dicastillo, O.; Serrano-Monzó, I.; Belintxon, M.; Bermejo-Martins, E.; Mujika, A. (2021) [29] Spain | Placing myself in a new normalized life: The process of becoming a first-time father. A grounded theory study. | To explore the process of men becoming first-time fathers and the experiences and challenges involved. | Qualitative research to explore the experiences of 14 men during pregnancy and childbirth in different stages of pregnancy, childbirth, and the postpartum period. | Nurses should take into account the process of men’s transition to fatherhood, enabling a comprehensive understanding of their perspectives and needs at each stage of this transition. | Small sample size and the focus on men whose partners had singleton pregnancies without health risks. |

References

- Kaakinen, J.R. Family Health Care Nursing (Chapter 1). In Family Health Care Nursing: Theory, Practice, and Research, 6th ed.; Kaakinen, J.R., Coehlo, D.P., Steele, R., Robinson, M., Eds.; F.A. Davis Company: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- ICN. ICNP Browser: Family. 2023. Available online: https://www.icn.ch/what-we-do/projects/e-health-icnptm/icnp-browser (accessed on 24 September 2023).

- Bertalanffy, L.V. General System Theory: Foundations, Development, Applications; George Brazillier: New York, NY, USA, 1968; ISBN 978-0807604533. [Google Scholar]

- Feinberg, M.; Hotez, E.; Roy, K.; Ledford, C.J.W.; Lewin, A.B.; Perez-Brena, N.; Childress, S.; Berge, J.M. Family Health Development: A Theoretical Framework. Pediatrics 2022, 149, e2021053509I. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, F. Family resilience: A developmental systems framework. Eur. J. Dev. Psychol. 2016, 13, 313–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meleis, A.I.; Sawyer, L.M.; Im, E.O.; Messias, D.K.H.; Schumacher, K.L. Experiencing Transitions: An Emerging Middle-Range Theory. In Transitions Theory Middle-Range and Situation-Specific Theories in Nursing Research and Practice; Meleis, A.I., Ed.; Springer Publishing Company: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 52–64. [Google Scholar]

- Chick, N.; Meleis, A.I. Transitions: A Nursing Concern. In Transitions Theory Middle-Range and Situation-Specific Theories in Nursing Research and Practice; Meleis, A.I., Ed.; Springer Publishing Company: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 24–37. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, C.; Pinto, C.; Martins, C. Transition to Fatherhood in the Prenatal Period: A Qualitative Study. Ciência Saúde Coletiva 2021, 26, 465–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eddy, B.; Fife, S. Active Husband Involvement During Pregnancy: A Grounded Theory. Fam. Relations 2020, 70, 1222–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manjrekar, S.; Patil, S. Perception and attitude toward mental illness in antenatal mothers in rural population of Southern India: A cross-sectional study. J. Neurosci. Rural. Pract. 2018, 9, 473–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Shi, H.; Chen, C.; Ren, Z.; Li, X.; Pu, Y.; Cui, L.; Wang, S.; Zhao, J.; Liu, H.; et al. Association between pregnant specific stress and depressive symptoms in the late pregnancy of Chinese women: The moderate role of family relationship and leisure hobbies. J. Public Health 2024, 32, 145–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eick, S.M.; Goin, D.E.; Izano, M.A.; Cushing, L.; DeMicco, E.; Padula, A.M.; Woodruff, T.J.; Morello-Frosch, R. Relationships between psychosocial stressors among pregnant women in San Francisco: A path analysis. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0234579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuersten-Hogan, R.; McHale, J.P. The Transition to Parenthood: A Theoretical and Empirical Overview. In Prenatal Family Dynamics; Kuersten-Hogan, R., McHale, J.P., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ordem dos Enfermeiros. Order of Nurses Position Statement on Family Nursing Referencial. 2023. Available online: https://www.ordemenfermeiros.pt/media/28497/tomada-de-posic-a-o-1-2023_mceec_referencial-em-enfermagem-de-sau-de-familiar.pdf (accessed on 3 January 2024).

- International Family Nursing Association. IFNA Position Statement on Generalist Competencies for Family Nursing Practice. 2015. Available online: https://internationalfamilynursing.org/2015/07/31/ifna-position-statement-on-generalist-competencies-for-family-nursing-practice/ (accessed on 3 January 2024).

- International Family Nursing Association. IFNA Position Statement on Advanced Practice Competencies for Family Nursing. 2017. Available online: https://internationalfamilynursing.org/2017/05/19/advanced-practice-competencies/ (accessed on 3 January 2024).

- Frosch, C.; Schoppe-Sullivan, S.O.D. Parenting and Child Development: A Relational Health Perspective. Am. J. Lifestyle Med. 2019, 15, 45–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coyne, I.; Holmström, I.; Söderbäck, M. Centeredness in Healthcare: A Concept Synthesis of Family-centered Care, Person-centered Care and Child-centered Care. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2018, 42, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostlund, U.; Bäckström, B.; Lindh, V.; Sundin, K.; Saveman, B. Nurses’ fidelity to theory-based core components when implementing Family Health Conversations – a qualitative inquiry. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 2015, 29, 582–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deepika; Rani, S.; Rahman, J. Patient and Family Centered Care: Practices in Pediatrics. Int. J. Nurs. Educ. 2020, 12, 44–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Condon, E.M. Maternal, Infant, and Early Childhood Home Visiting: A Call for a Paradigm Shift in States’ Approaches to Funding. Policy Politics Nurs. Pract. 2019, 20, 28–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thürlimann, E.; Verweij, L.; Naef, R. The Implementation of Evidence-Informed Family Nursing Practices: A Scoping Review of Strategies, Contextual Determinants, and Outcomes. J. Fam. Nurs. 2022, 28, 258–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ridgway, L.; Hackworth, N.; Nicholson, J.M.; McKenna, L. Working with families: A systematic scoping review of family-centred care in universal, community-based maternal, child, and family health services. J. Child Health Care 2021, 25, 268–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peters, M.; Godfrey, C.; McInerney, P.; Munn, Z.; Tricco, A.; Khalil, H. Chapter 11: Scoping Reviews (2020 version). In JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis; Aromataris, E., Munn, Z., Eds.; JBI: North Adelaide, SA, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.D.J.; Marnie, C.; Tricco, A.C.; Pollock, D.; Munn, Z.; Alexander, L.; McInerney, P.; Godfrey, C.M.; Khalil, H. Updated methodological guidance for the conduct of scoping reviews. JBI Evid. Synth. 2020, 18, 2119–2126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.; Colquhoun, H.; Peters, M.; Akl, E.; Stewart, L.; Wilson, M.; Godfrey, C.; Soares-Weiser, K.; Tunçalp, O. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nomaguchi, K.; Milkie, M. Parenthood and Well-Being: A Decade in Review. J. Marriage Fam. 2020, 82, 198–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrade, F.M.R.; Simões Figueiredo, A.; Capelas, M.L.; Charepe, Z.; Deodato, S. Experiences of Homeless Families in Parenthood: A Systematic Review and Synthesis of Qualitative Evidence. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vidaurreta, M.; Lopez-Dicastillo, O.; Serrano-Monzó, I.; Belintxon, M.; Bermejo-Martins, E.; Mujika, A. Placing myself in a new normalized life: The process of becoming a first-time father. A grounded theory study. Nurs. Health Sci. 2022, 24, 152–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hickey, G.; McGilloway, S.; Leckey, Y.; Stokes, A. A Universal Early Parenting Education Intervention in Community-Based Primary Care Settings: Development and Installation Challenges. Educ. Sci. 2018, 8, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agu, A.P.; Akamike, I.C.; Okedo-Alex, I.N.; Umeokonkwo, A.A.; Ogbonna-Igwenyi, C.O.; Madumere, O.D.; Keke, C.O. Predictors of knowledge and practice of newborn care among post-natal mothers attending immunisation clinics in Southeast Nigeria. Ghana Med. J. 2022, 56, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piro, S.S.; Ahmed, H.M. Impacts of antenatal nursing interventions on mothers’ breastfeeding self-efficacy: An experimental study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2020, 20, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, R.; Isaia, A.; Schwartz, A.; Atkins, M. Encouraging Parenting Behaviors That Promote Early Childhood Development Among Caregivers From Low-Income Urban Communities: A Randomized Static Group Comparison Trial of a Primary Care-Based Parenting Program. Matern. Child Health J. 2019, 23, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herval, A.; Dumont, D.P.; Gomes, V.E.; Vargas, A.M.D.; Schaller, B. Health education strategies targeting maternal and child health: A scoping review of educational methodologies. Medicine 2019, 98, e16174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alobaysi, H.; Jahan, S. Infant care practices among mothers attending well-baby clinics at primary health care centers in Unaizah city. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 2022, 11, 4766–4772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salih, B.B.; Khaleel, M.A. A Study on Pregnant Mothers’ Knowledge and Self-Management Toward Prenatal Care Services in Baghdad City. HIV Nurs. 2022, 22, 360–364. [Google Scholar]

- Massi, L.; Hickey, S.; Maidment, S.J.; Roe, Y.; Kildea, S.; Nelson, C.; Kruske, S. Improving interagency service integration of the Australian Nurse Family Partnership Program for First Nations women and babies: A qualitative study. Int. J. Equity Health 2021, 20, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sacks, E.; Freeman, P.A.; Sakyi, K.; Jennings, M.C.; Rassekh, B.M.; Gupta, S.; Perry, H.B. Comprehensive review of the evidence regarding the effectiveness of community-based primary health care in improving maternal, neonatal and child health: 3. neonatal health findings. J. Glob. Health 2017, 7, 355–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angelhoff, C.; Askenteg, H.; Wikner, U.; Edéll-Gustafsson, U. “To Cope with Everyday Life, I Need to Sleep”—A Phenomenographic Study Exploring Sleep Loss in Parents of Children with Atopic Dermatitis. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2018, 43, e59–e65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dlamini, L.P.; Hsu, Y.Y.; Shongwe, M.C.; Wang, S.T.; Gau, M.L. Maternal Self-Efficacy as a Mediator in the Relationship Between Postpartum Depression and Maternal Role Competence: A Cross-Sectional Survey. J. Midwifery Women’s Health 2023, 68, 499–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajipour, M.; Soltani, M.; Safari-Faramani, R.; Khazaei, S.; Etemad, K.; Rahmani, S.; Valadbeigi, T.; Yaghoobi, H.; Rezaeian, S. Maternal Sleep and Related Pregnancy Outcomes: A Multicenter Cross-Sectional Study in 11 Provinces of Iran. J. Fam. Reprod. Health 2021, 15, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopwood, N.; Clerke, T.; Nguyen, A. A pedagogical framework for facilitating parents’ learning in nurse-parent partnership. Nurs. Inq. 2018, 25, e12220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savci Bakan, A.B.; Aktas, B.; Yalcinoz Baysal, H.; Aykut, N. An Investigation of Pregnant Women’s Attitudes Towards Childhood Vaccination and Trust in Health Services. Matern. Child Health J. 2023, 27, 1051–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strobel, N.; Chamberlain, C.; Campbell, S.; Shields, L.; Bainbridge, R.; Adams, C.; Edmond, K.; Marriott, R.; McCalman, J. Family-centred interventions for Indigenous early childhood well-being by primary healthcare services. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2022, 12, 1–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daelmans, B.; Manji, S.A.; Raina, N. Nurturing Care for Early Childhood Development: Global Perspective and Guidance. Indian Pediatr. 2021, 58, S11–S15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, S.E.; Fredericks, E.M.; Janisse, H.C.; Cousino, M.K. Systematic review of father involvement and child outcomes in pediatric chronic illness populations. J. Clin. Psychol. Med. Settings 2020, 27, 89–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, W.; Liu, Y.; Lv, H.; Ge, J.; Meng, Y.; Zhao, N.; Zhao, N.; Guo, Q.; Hu, J. Effects of family relationship and social support on the mental health of Chinese postpartum women. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2022, 22, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hickey, G.; McGilloway, S.; Leckey, Y.; Leavy, S.; Stokes, A.; O’Connor, S.; Donnelly, M.; Bywater, T. Exploring the potential utility and impact of a universal, multi-component early parenting intervention through a community-based, controlled trial. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2020, 118, 105458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckenrode, J.; Campa, M.I.; Morris, P.A.; Henderson, C.R.; Bolger, K.E.; Kitzman, H.; Olds, D.L. The Prevention of Child Maltreatment Through the Nurse Family Partnership Program: Mediating Effects in a Long-Term Follow-Up Study. Child Maltreatment 2017, 22, 92–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffee, J.H.; Mendelsohn, A.L.; Kuo, A.A.; Legano, L.A.; Earls, M.F.; Chilton, L.A.; Flanagan, P.J.; Dilley, K.J.; Green, A.E.; Gutierrez, J.R.; et al. Early Childhood Home Visiting. Pediatrics 2017, 140, e20172150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masten, A.S.; Barnes, A.J. Resilience in Children: Developmental Perspectives. Children 2018, 5, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aass, L.K.; Skundberg-Kletthagen, H.; Schrøder, A.; Moen, O.L. Young Adults and Their Families Living With Mental Illness: Evaluation of the Usefulness of Family-Centered Support Conversations in Community Mental Health Care Settings. J. Fam. Nurs. 2020, 26, 302–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsons, A.H.; Jones, C.A.; Surtees, A.D. Changes in parental sleep from pregnancy to postpartum: A meta-analytic review of actigraphy studies. Sleep Med. Rev. 2023, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, N.A.L.; Tam, W.W.; Shorey, S. Enhancing first-time parents’ self-efficacy: A systematic review and meta-analysis of universal parent education interventions’ efficacy. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2018, 82, 149–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-Liria, R.; Vargas-Muñoz, E.; Aguilar-Parra, J.M.; Padilla-Góngora, D.; Mañas-Rodriguez, M.A.; Rocamora-Pérez, P. Effectiveness of a Training Program in the Management of Stress for Parents of Disabled Children. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2020, 29, 964–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO—World Health Organization. Breastfeeding. 2023. Available online: https://www.who.int/health-topics/breastfeeding (accessed on 21 November 2023).

- Bastos, F.; Cruz, I.; Campos, J.; Brito, A.; Parente, P.; Morais, E. Representação do conhecimento em enfermagem—A família como cliente. Rev. Investig. Inovação Saúde 2022, 5, 81–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eggenberger, S.K.; Sanders, M. A family nursing educational intervention supports nurses and families in an adult intensive care unit. Aust. Crit. Care 2016, 29, 217–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Authors and Year | Country | Methods and Participants | Main Implications for Family Nursing |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nomaguchi; Milkie 2020 [27] | Canada | Literature review | Consideration should be given to the impact of child-rearing stressors. It is crucial to recognize factors such as socioeconomic status, gender, partnership status, and race/ethnicity. Parental well-being should be a focal point in both pre- and postnatal care. |

| Andrade et al., 2020 [28] | Portugal | Systematic review | Families, fathers, or mothers living in adverse conditions should be considered in tailoring nursing interventions accordingly. It is crucial to address their specific needs and challenges during the care planning process. |

| Vidaurreta et al., 2021 [29] | Spain | Qualitative research; 14 men | The process of men’s transition to fatherhood should be considered, enabling a comprehensive understanding of their perspectives and needs at each stage of this journey. |

| Hickey et al., 2018 [30] | Ireland | Controlled trial; 190 parents | Creating a welcoming environment for interagency parenting support is crucial. The objective is to engage and empower parents through evidence-based prevention and early intervention. |

| Agu, A. et al., 2022 [31] | Nigeria | Cross-sectional study; 400 participants | It is crucial to consider the impact of community resources, families’ characteristics, and family support in the transition to parenthood. |

| Piro; Ahmed 2020 [32] | Iraq | Experimental investigation; 130 pregnant women | The effective provision of antenatal breastfeeding education enhances breastfeeding self-efficacy, fostering increased self-confidence, knowledge, and positive attitudes toward the practice of breastfeeding. |

| Shah et al., 2019 [33] | USA | Randomized controlled trial; 40 participants | Through SDP, nurses can actively promote positive parenting behaviors, such as cognitive stimulation, providing learning materials, and enhancing the quality of parent–child verbal interactions. These efforts improve developmental outcomes for children. |

| Herval et al., 2019 [34] | Brazil | Scoping review | Sustaining health education strategies, with a particular emphasis on improving breastfeeding practices, is one crucial approach that can be employed to enhance maternal and child outcomes. |

| Alobaysi; Jahan 2022 [35] | Saudi Arabia | Cross-sectional study; 200 mothers | To enhance infant care practices, it is important to address certain aspects of child care and strengthen health education initiatives for mothers. |

| Salih; Khalee 2022 [36] | Iraq | Descriptive cross-sectional study; 206 pregnant women | Establishing additional and consistent instructions for prenatal care within primary health centers is recommended to reduce complications during and after pregnancy. |

| Massi et al., 2021 [37] | Australia | Qualitative study; 76 participants | The ANFPP supports women on their journey to motherhood by providing home visits, health education, guidance, and social and emotional support. This approach aims to enhance child outcomes. |

| Sacks et al., 2017 [38] | USA | Systematic review | CBPHC can significantly enhance neonatal health. Key strategies include home visitation, education on preventing complications, recognizing alarming signs, providing early treatment or referrals for neonatal illnesses, early immunization, outreach by mobile teams, and participatory women’s groups. |

| Angelhoff et al., 2018 [39] | Sweden | Qualitative interview study; 12 parents | Sleep deprivation in parents of young children with AD should be promptly identified to prevent adverse outcomes affecting overall family well-being. |

| Dlamini, L. et al., 2023 [40] | Taiwan | Cross-sectional study; 343 postpartum mothers | Addressing depressive symptoms during the postpartum period is imperative to mitigate the risk of low maternal self-confidence and inadequate caregiving skills. |

| Hajipour et al., 2021 [41] | Iran | Multicentered cross-sectional study; 3675 pregnant women across 11 provinces | In addressing the impact of sleep quality on maternal outcomes, it is essential to plan and implement appropriate interventions within the realm of primary healthcare. |

| Hopwood; Clerke; Nguyen 2018 [42] | Australia | Descriptive study; 19 nurses and 60 parents from 58 different families | Through observation of various aspects and interactions of children and parents, nurses can build on the strengths of parents. |

| Savci et al., 2023 [43] | Turkey | Descriptive study; 193 pregnant women | Ensuring that children receive vaccinations is crucial for their overall health and well-being. Primary care community health nurses play a pivotal role in providing accurate information to parents to promote children vaccination. |

| Strobel et al., 2022 [44] | Australia | Systematic review | Family-centered care provided by primary healthcare services prioritizes elements such as the environment, communication, education, counseling, and support for families. It aims to improve the health and well-being of children, parents, and their families. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

César-Santos, B.; Bastos, F.; Dias, A.; Campos, M.J. Family Nursing Care during the Transition to Parenthood: A Scoping Review. Healthcare 2024, 12, 515. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12050515

César-Santos B, Bastos F, Dias A, Campos MJ. Family Nursing Care during the Transition to Parenthood: A Scoping Review. Healthcare. 2024; 12(5):515. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12050515

Chicago/Turabian StyleCésar-Santos, Bruna, Fernanda Bastos, António Dias, and Maria Joana Campos. 2024. "Family Nursing Care during the Transition to Parenthood: A Scoping Review" Healthcare 12, no. 5: 515. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12050515

APA StyleCésar-Santos, B., Bastos, F., Dias, A., & Campos, M. J. (2024). Family Nursing Care during the Transition to Parenthood: A Scoping Review. Healthcare, 12(5), 515. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12050515