An Epidemiological Study of Cervical Cancer Trends among Women with Human Immunodeficiency Virus

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Description

2.2. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Populations of Interest

3.2. Changes in Cervical Cancer Rates Based on Age

3.3. Geographic Variations in HIV and Cervical Cancer

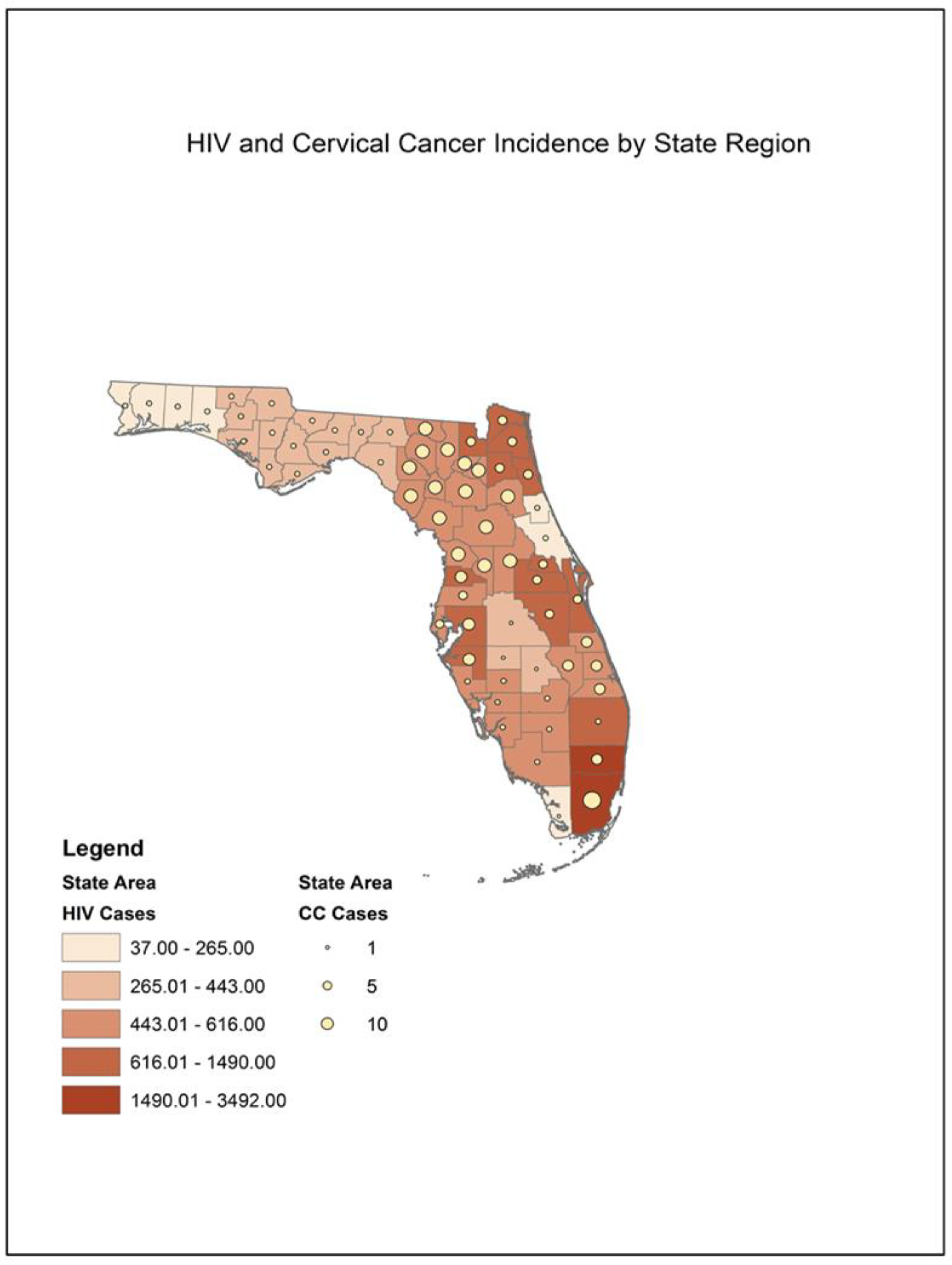

3.4. Geographic Variations in HIV and Cervical Cancer

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Implications for Policy and Practice

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Curtin, S.C.; Tejada-Vera, B.; Bastian, B.A. Deaths: Leading Causes for 2020; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Hyattsville, MD, USA, 2023; p. 114.

- American Cancer Society. Key Statistics for Cervical Cancer. How Common Is Cervical Cancer? American Cancer Society: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- American Cancer Society. What Is Cervical Cancer? American Cancer Society: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- American Cancer Society. Risk Factors for Cervical Cancer. Cervical Cancer Causes, Risk Factors, and Prevention; American Cancer Society: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Sausen, D.G.; Shechter, O.; Gallo, E.S.; Dahari, H.; Borenstein, R. Herpes Simplex Virus, Human Papillomavirus, and Cervical Cancer: Overview, Relationship, and Treatment Implications. Cancers 2023, 15, 3692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cutrell, J.; Bedimo, R. Non-AIDS-defining Cancers among HIV-Infected Patients. Curr. HIV/AIDS Rep. 2013, 10, 207–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Ramírez, R.U.; Shiels, M.S.; Dubrow, R.; Engels, E.A. Cancer risk in HIV-infected people in the USA from 1996 to 2012: A population-based, registry-linkage study. Lancet HIV 2017, 4, e495–e504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shiels, M.P.; Ruth, M.; Gail, M.H.; Hall, I.H.; Li, J.; Chaturvedi, A.K.; Bhatia, K.; Uldrick, T.S.; Yarchoan, R.; Goedert, J.J.; et al. Cancer Burden in the HIV-Infected Population in the United States. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2011, 103, 753–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castle, P.E.E.; Mark, H.; Sahasrabuddhe, V.V. Cervical Cancer Prevention and Control in Women Living with Human Immunodeficiency Virus. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2021, 71, 455–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shiels, M.S.E.; Eric, A. Evolving Epidemiology of HIV-associated Malignancies. Curr. Opin. HIV AIDS 2017, 12, 6–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahangdale, L.; Sarnquist, C.; Yavari, A.; Blumenthal, P.; Israelski, D. Frequency of Cervical Cancer and Breast Cancer Screening in HIV–Infected Women in a County-Based HIV Clinic in the Western United States. J. Women’s Health 2010, 19, 709–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnes, A.; Betts, A.C.; Borton, E.K.; Sanders, J.M.; Pruitt, S.L.; Werner, C.; Bran, A.; Estelle, C.D.; Balasubramanian, B.A.; Inrig, S.J.; et al. Cervical cancer screening among HIV infected women in an urban, U.S. safety-net healthcare system. AIDS 2018, 32, 1861–1870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Office of AIDS Research Advisory Council (OARAC). Guidelines for the Prevention and Treatment of Opportunistic Infections in Adults and Adolescents with HIV. Women with HIV Infection 2021. Available online: https://clinicalinfo.hiv.gov/sites/default/files/guidelines/documents/adult-adolescent-oi/guidelines-adult-adolescent-oi.pdf (accessed on 22 February 2024).

- Li, S.; Wen, X. Seropositivity to Herpes Simplex Virus Type 2, but not Type 1 is Associated with Cervical Cancer: NHANES (1999–2014). BMC Cancer 2017, 17, 726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bahena-Román, M.; Sánchez-Alemán, M.A.; Contreras-Ochoa, C.O.; Lagunas-Martínez, A.; Olamendi-Portugal, M.; López-Estrada, G.; Delgado-Romero, K.; Guzmán-Olea, E.; Madrid-Marina, V.; Torres-Poveda, K. Prevalance of Active Infection by Herpes Simplex Virus Type 2 in Patients with High-Risk Huan Papillomavirus Infection: A Cross-Sectional Study. J. Med. Virol. 2020, 92, 1246–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luther, K.M.M.; Annie, N.N.; Grace, D.N.; Michel, W.; Charlotte, B.E.; Henri, A.Z.P. Association of Cervical Inflammation and Cervical Abnormalities in Women Infected with Herpes Simplex Virus Type 2. Int. J. Trop. Med. Public Health 2014, 1, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Ballinger, G.A. Using Generalized Estimating Equations for Longitudinal Data Analysis. Organ. Res. Methods 2004, 7, 127–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nissim, O.; Dees, A.; Cooper, S.L.; Patel, K.; Lazenby, G.B. Cervical Cancer Among Women With HIV in South Carolina During the Era of Effective Antiretroviral Therapy. J. Low. Genit. Tract Dis. 2022, 26, 109–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stier, E.A.; Engels, E.; Horner, M.J.; Robinson, W.T.; Qiao, B.; Hayes, J.; Bayakly, R.; Anderson, B.J.; Gonsalves, L.; Pawlish, K.S.; et al. Cervical cancer incidence stratified by age in women with HIV compared with the general population in the United States, 2002–2016. AIDS 2021, 35, 1851–1856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, G.; Koroukian, S.M.; Navale, S.M.; Schiltz, N.K.; Kim, U.; Rose, J.; Cooper, G.S.; Moore, S.E.; Mintz, L.J.; Avery, A.K.; et al. Cancer Burden in Women with HIV on Medicaid: A Nationwide Analysis. Women’s Health 2023, 19, 17455057231170061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grover, S.; Bhatia, R.; Friebel-Klingner, T.M.; Mathoma, A.; Vuylsteke, P.; Khan, S.; Ralefala, T.; Tawe, L.; Bazzett-Matabele, L.; Monare, B.; et al. Cervical Cancer Screening in HIV-endemic Countries: An Urgent Call For Guideline Change. Cancer Treat. Res. Commun. 2023, 34, 100682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernstein, W.B.; Little, R.F.; Wilson, W.H.; Yarchoana, R. Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome-Related Malignancies in the Era of Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy. Int. J. Hematol. 2006, 84, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Office of National AIDS Policy. National HIV/AIDS Strategy: Updated to 2020. April 2022. Available online: https://ryanwhite.hrsa.gov/about/national-strategies (accessed on 22 February 2024).

- Office of National AIDS Policy. National HIV/AIDS Strategy 2023 Interim Action Report. What Is the National HIV/AIDS Strategy 2023. Available online: https://files.hiv.gov/s3fs-public/2023-12/National-HIV-AIDS-Strategy-2023-Interim-Action-Report.pdf (accessed on 22 February 2024).

- Office of National AIDS Policy. HIV Care Continuum. What Is the HIV Care Continuum? 2022. Available online: https://www.hiv.gov/federal-response/policies-issues/hiv-aids-care-continuum/ (accessed on 24 February 2024).

- Curry, S.J.; Krist, A.H.; Owens, D.K.; Barry, M.J.; Caughey, A.B.; Davidson, K.W.; Doubeni, C.A.; Epling, J.W.; Kemper, A.R.; Kubik, M.; et al. Screening for Cervical Cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2018, 320, 674–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suk, R.; Hong, Y.R.; Rajan, S.S.; Xie, Z.; Zhu, Y.; Spencer, J.C. Assessment of US Preventive Services Task Force Guideline-Concordant Cervical Cancer Screening Rates and Reasons for Underscreening by Age, Race and Ethnicity, Sexual Orientation, Rurality, and Insurance, 2005 to 2019. JAMA Netw. Open 2022, 5, e2143582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| HIV | Cervical Cancer | HSV-2 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||

| White | 2142 | (14.1) | 19 | (20.4) | 52 | (11.1) |

| Black | 10,748 | (70.9) | 65 | (69.9) | 349 | (74.6) |

| Hispanic | 1878 | (12.4) | 9 | (9.7) | 58 | (12.4) |

| Asian | 29 | (0.2) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) |

| Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander | 2 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) |

| Native American | 10 | (0.1) | 0 | (0.0) | 0 | (0.0) |

| Multi-racial | 345 | (2.3) | 0 | (0.0) | 9 | (1.9) |

| Unknown | 5 | (0.0) | 27 | (29.0) | 0 | (0.0) |

| Total | 15,159 | 93 | 468 | |||

| Year | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ages | ||||||||||||

| 13–19 yrs | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | - |

| 20–29 yrs | 4.67 | 14.02 | 12.99 | 8.51 | 4.95 | 4.98 | 0.00 | 5.46 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | <0.01 |

| 30–39 yrs | 21.84 | 9.71 | 6.52 | 8.47 | 14.81 | 0.00 | 4.75 | 0.00 | 5.29 | 10.75 | 7.49 | 0.12 |

| 40–49 yrs | 23.32 | 7.69 | 8.83 | 3.63 | 2.13 | 9.11 | 4.34 | 2.42 | 10.20 | 9.40 | 6.85 | 0.62 |

| 50+ yrs | 9.66 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 7.07 | 7.17 | 7.41 | 0.00 | 3.17 | 3.13 | 11.24 | 0.00 | 0.69 |

| Overall | 11.90 | 6.28 | 5.67 | 5.54 | 5.81 | 4.30 | 1.82 | 2.21 | 3.72 | 6.28 | 2.87 | 0.11 |

| HIV | HIV/HSV-2 | HIV/Cervical Cancer | HIV/HSV-2 and Cervical Cancer | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases | 14,603 | 463 | 88 | 5 | 15,159 |

| Percentage | 96.3% | 3.1% | 0.6% | 0.03% | 100% |

| Year | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ages | ||||||||||||

| 13–19 yrs | 17.65 | 15.38 | 10.53 | 0.00 | 20.00 | 0.00 | 5.00 | 18.75 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 12.50 | 0.15 |

| 20–29 yrs | 5.58 | 7.52 | 6.61 | 6.40 | 2.01 | 2.30 | 5.31 | 1.08 | 1.25 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.03 * |

| 30–39 yrs | 4.36 | 4.17 | 2.71 | 2.83 | 1.48 | 2.69 | 2.34 | 0.54 | 0.00 | 0.89 | 0.93 | 0.01 * |

| 40–49 yrs | 3.13 | 3.93 | 2.76 | 2.59 | 3.27 | 1.49 | 3.05 | 2.84 | 1.10 | 0.79 | 1.11 | 0.02 * |

| 50+ yrs | 2.89 | 3.80 | 2.39 | 1.59 | 4.24 | 0.87 | 0.44 | 1.42 | 0.62 | 0.65 | 0.74 | 0.01 * |

| Overall | 4.04 | 4.74 | 3.49 | 2.97 | 3.16 | 1.73 | 2.51 | 1.96 | 0.69 | 0.63 | 1.00 | 0.001 * |

| Parameter | β | SE | 95% CI | Wald Chi-Square | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Upper | Lower | |||||

| Intercept | 2.102 | 0.13 | 1.84 | 2.36 | 256.28 | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mathis, A.; Smith, U.D.; Crowther, V.; Lee, T.; Suther, S. An Epidemiological Study of Cervical Cancer Trends among Women with Human Immunodeficiency Virus. Healthcare 2024, 12, 1178. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12121178

Mathis A, Smith UD, Crowther V, Lee T, Suther S. An Epidemiological Study of Cervical Cancer Trends among Women with Human Immunodeficiency Virus. Healthcare. 2024; 12(12):1178. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12121178

Chicago/Turabian StyleMathis, Arlesia, Ukamaka D. Smith, Vanessa Crowther, Torhonda Lee, and Sandra Suther. 2024. "An Epidemiological Study of Cervical Cancer Trends among Women with Human Immunodeficiency Virus" Healthcare 12, no. 12: 1178. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12121178

APA StyleMathis, A., Smith, U. D., Crowther, V., Lee, T., & Suther, S. (2024). An Epidemiological Study of Cervical Cancer Trends among Women with Human Immunodeficiency Virus. Healthcare, 12(12), 1178. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12121178