Effectiveness of Peer Support Programs for Severe Mental Illness: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

2.2. Study Design

2.3. PICO (Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome)

2.3.1. Population

2.3.2. Intervention

2.3.3. Comparator

2.3.4. Outcomes

2.4. Search Strategy

2.4.1. Search Methods

2.4.2. Study Selection and Data Extraction

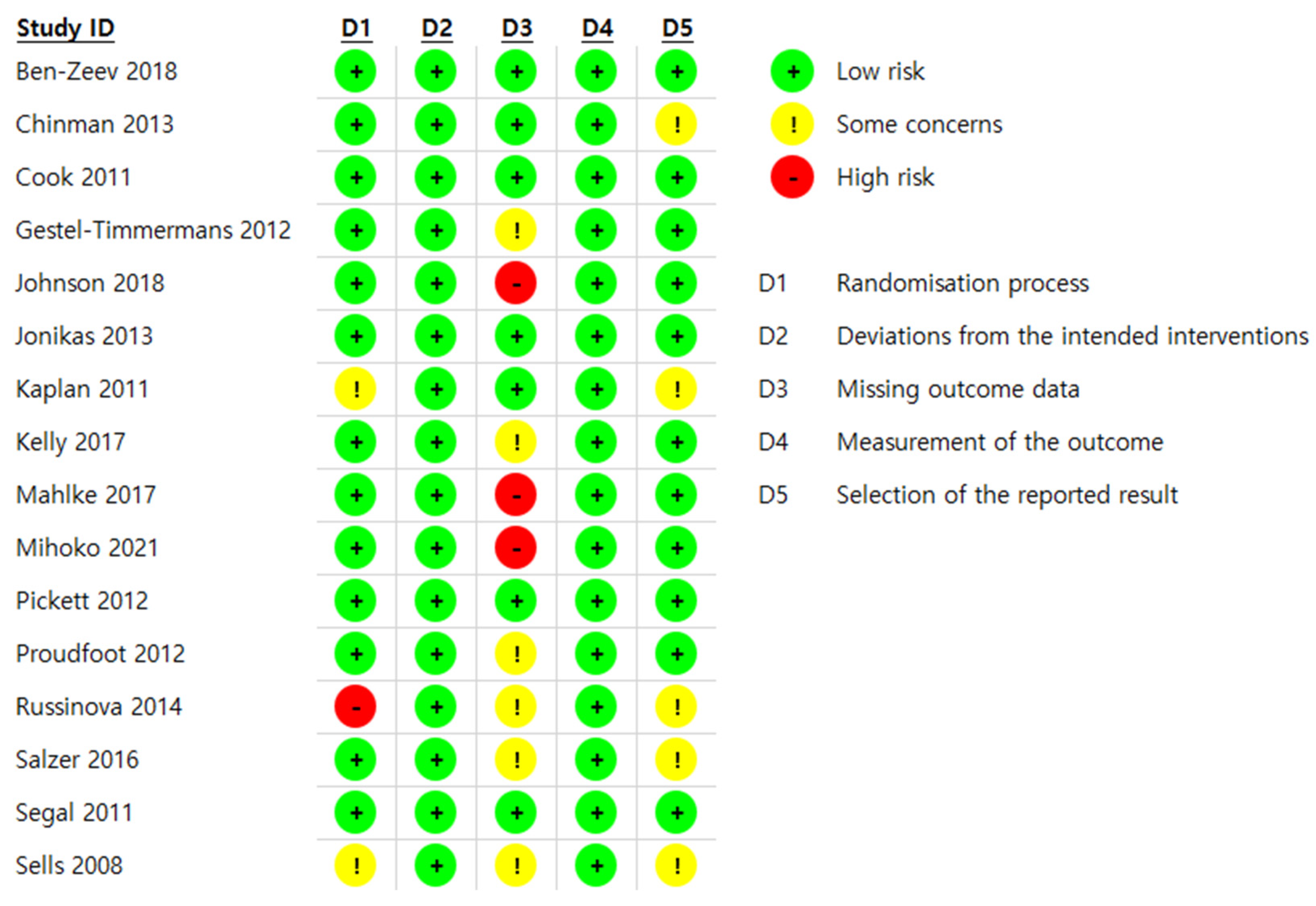

2.4.3. Assessment of Risk of Bias

2.4.4. Analysis Methods

2.4.5. Tests of Heterogeneity

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Included RCTs

3.2. Study Characteristics of the Measured Outcomes

3.3. Risk of Bias

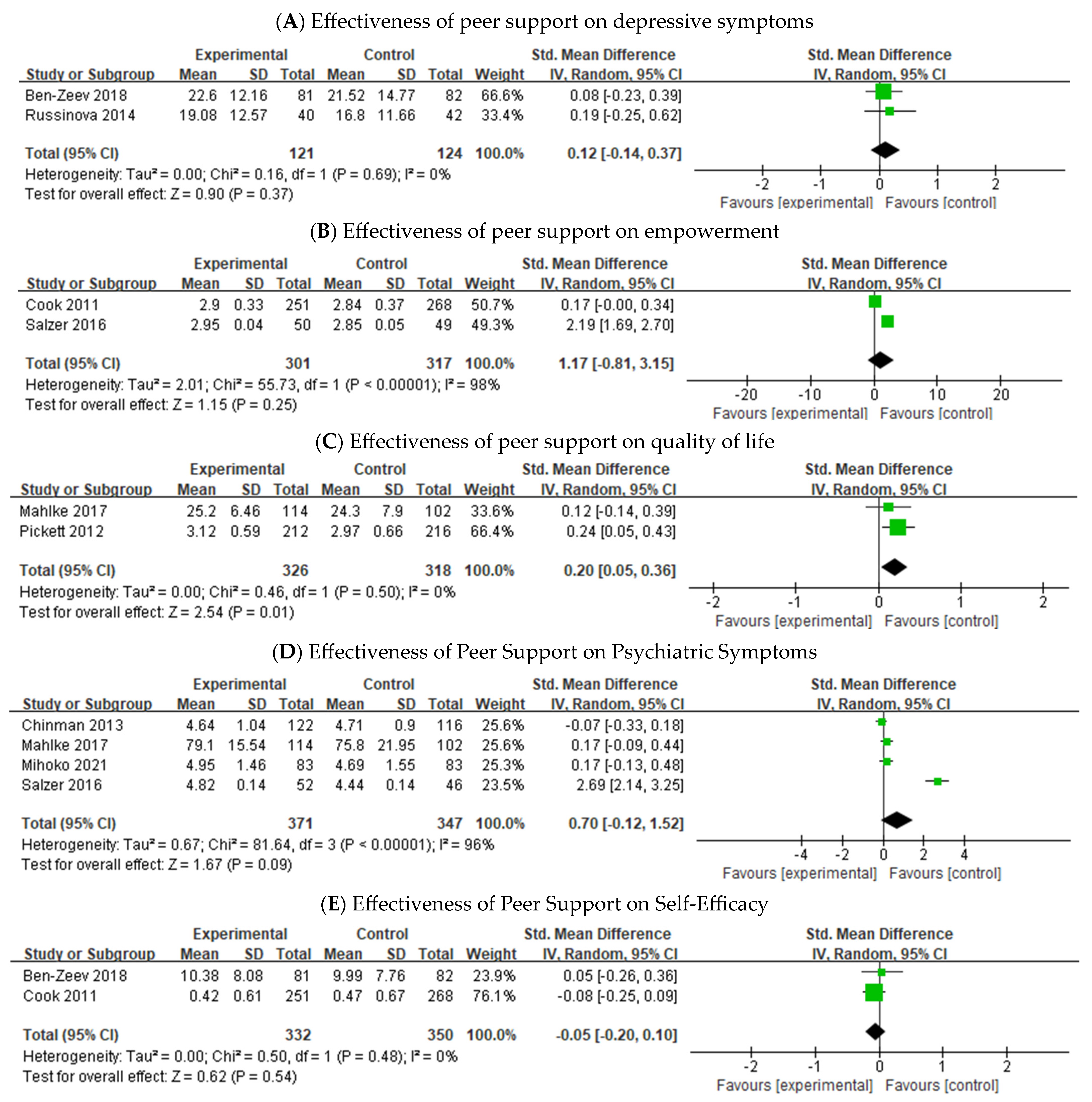

3.4. Effectiveness of Peer Support on Individuals with SMI

4. Discussion

4.1. Findings

4.2. Limitations

4.3. Suggestions

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- De Hert, M.; Correll, C.U.; Bobes, J.; Cetkovich-Bakmas, M.; Cohen, D.; Asai, I.; Detraux, J.; Gautam, S.; Möller, H.J.; Ndetei, D.M.; et al. Physical illness in patients with severe mental disorders. I. prevalence, impact of medications and disparities in health care. World J. Psychiatry 2011, 10, 52–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Mental Disorders Affect One in Four People. Available online: https://www.who.int/whr/2001/media_centre/press_release/en/ (accessed on 1 April 2024).

- Saha, S.; Chant, D.; Welham, J.; McGrath, J. A systematic review of the prevalence of schizophrenia. PLoS Med. 2005, 2, e141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schinnar, A.P.; Rothbard, A.B.; Kanter, R.; Jung, Y.S. An empirical literature review of definitions of severe and persistent mental illness. Am. J. Psychiatry 1990, 147, 1602–1608. [Google Scholar]

- Killaspy, H.; Marston, L.; Omar, R.Z.; Green, N.; Harrison, I.; Lean, M.; Holloway, F.; Craig, T.; Leavey, G.; King, M. Service quality and clinical outcomes: An example from mental health rehabilitation services in England. Br. J. Psychiatry 2013, 202, 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, P.D.; Strassnig, M. Predicting the severity of everyday functional disability in people with schizophrenia: Cognitive deficits, functional capacity, symptoms, and health status. World J. Psychiatry 2012, 11, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dalton-Locke, C.; Marston, L.; McPherson, P.; Killaspy, H. The effectiveness of mental health rehabilitation services: A systematic review and narrative synthesis. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 11, 607933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anthony, W.A. Recovery from mental illness: The guiding vision of the mental health service system in the 1990s. Psychosoc. Rehabil. J. 1993, 16, 11–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, L.; Roe, D. Recovery from versus recovery in serious mental illness: One strategy for lessening confusion plaguing recovery. J. Ment. Health 2007, 16, 459–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Weeghel, J.; Van Zelst, C.; Boertien, D.; Hasson-Ohayon, I. Conceptualizations, assessments and implications of personal recovery from mental illness: A scoping review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Psychiatr. Rehabil. J. 2019, 42, 169–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mead, S.; Hilton, D.; Curtis, L. Peer support: A theoretical perspective. Psychiatr. Rehabil. J. 2001, 25, 134–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leamy, M.; Bird, V.; Le Boutillier, C.; Williams, J.; Slade, M. Conceptual framework for personal recovery in mental health: Systematic review and narrative synthesis. Br. J. Psychiatry 2011, 199, 445–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peck, C.K.H.; Thangavelu, D.P.; Li, Z.; Goh, Y.S. Effects of peer-delivered self-management, recovery education interventions for individuals with severe and enduring mental health challenges: A meta-analysis. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2023, 30, 54–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, L.; Chinman, M.; Sells, D.; Rowe, M. Peer support among adults with serious mental illness: A report from the field. Schizophr. Bull. 2006, 32, 443–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slade, M.; Amering, M.; Farkas, M.; Hamilton, B.; O’Hagan, M.; Panther, G.; Perkins, R.; Shepherd, G.; Tse, S.; Whitley, R. Uses and abuses of recovery: Implementing recovery-oriented practices in mental health systems. World Psychiatry 2014, 13, 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Ma, N.; Ma, L.; Zhang, W.; Xu, W.; Shi, R.; Chen, H.; Lamberti, J.S.; Caine, E.D. Feasibility of peer support services among people with severe mental illness in China. BMC Psychiatry 2019, 19, 360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connell, M.J.; Sledge, W.H.; Staeheli, M.; Sells, D.; Costa, M.; Wieland, M.; Davidson, L. Outcomes of a peer mentor intervention for persons with recurrent psychiatric hospitalization. Psychiatr. Serv. 2018, 69, 760–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchinson, D.S.; Anthony, W.A.; Ashcraft, L.; Johnson, E.; Dunn, E.C.; Lyass, A.; Rogers, E.S. The personal and vocational impact of training and employing people with psychiatric disabilities as providers. Psychiatr. Rehabil. J. 2006, 29, 205–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trachtenberg, M.; Parsonage, M.; Shepherd, G.; Boardman, J. Peer Support in Mental Health Care: Is it Good Value for Money? Centre for Mental Health: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Repper, J.; Carter, T.A. review of the literature on peer support in mental health services. J. Ment. Health 2011, 20, 392–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinman, M.; George, P.; Dougherty, R.H.; Daniels, A.S.; Ghose, S.S.; Swift, A.; Delphin-Rittmon, M.E. Peer support services for individuals with serious mental illnesses: Assessing the evidence. Psychiatr. Serv. 2014, 65, 429–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Easter, M.M.; Swanson, J.W.; Robertson, A.G.; Moser, L.L.; Swartz, M.S. Impact of psychiatric advance directive facilitation on mental health consumers: Empowerment, treatment attitudes and the role of peer support specialists. J. Ment. Health 2021, 30, 585–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salzer, M.S.; Rogers, J.; Salandra, N.; O’Callaghan, C.; Fulton, F.; Balletta, A.A.; Pizziketti, K.; Brusilovskiy, E. Effectiveness of peer-delivered center for independent living supports for individuals with psychiatric disabilities: A randomized, controlled trial. Psychiatr. Rehabil. J. 2016, 39, 239–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segal, S.P.; Silverman, C.J.; Temkin, T.L. Outcomes from consumer-operated and community mental health services: A randomized controlled trial. Psychiatr. Serv. 2011, 62, 915–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloyd-Evans, B.; Mayo-Wilson, E.; Harrison, B.; Istead, H.; Brown, E.; Pilling, S.; Johnson, S.; Kendall, T. A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials of peer support for people with severe mental illness. BMC Psychiaty 2014, 14, 14–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, S.; Foster, R.; Marks, J.; Morshead, R.; Goldsmith, L.; Barlow, S.; Sin, J.; Gillard, S. The effectiveness of one-to-one peer support in mental health services: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry 2020, 20, 534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyons, N.; Cooper, N.; Lloyd-Evans, B. A systematic review and meta-analysis of group peer support interventions for people experiencing mental health conditions. BMC Psychiatry 2021, 21, 315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellamy, C.; Schmutte, C.; Davidson, L. An update on the growing evidence base for peer support. Ment. Health Soc. Incl. 2017, 21, 161–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortuna, K.L.; Solomon, P.; Rivera, J. An update of peer support/peer provided services underlying processes, benefits, and critical ingredients. Psychiatr Q. 2022, 93, 571–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weikel, K.; Tomer, A.; Davis, L.; Sieke, R. Recovery and self-efficacy of a newly trained certified peer specialist following supplemental weekly group supervision: A case-based time-series analysis. Am. J. Psychiatr. Rehabil. 2017, 20, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forbes, J.; Pratt, C.; Cronise, R. Experiences of peer support specialists supervised by nonpeer supervisors. Psychiatr. Rehabil. J. 2022, 45, 54–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gates, L.B.; Akabas, S.H. Developing strategies to integrate peer providers into the staff of mental health agencies. Adm Policy Ment. Health 2007, 34, 293–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.P.T.; Green, S. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions; Cochrane Collaboration: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. PLoS Med. 2021, 18, e1003583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalton, J.E.; Bolen, S.D.; Mascha, E.J. Publication bias: The elephant in the review. Anesth. Analg. 2016, 123, 812–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sells, D.; Black, R.; Davidson, L.; Rowe, M. Beyond generic support: Incidence and impact of invalidation in peer services for clients with severe mental illness. Psychiatr. Serv. 2008, 59, 1322–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proudfoot, J.; Parker, G.; Manicavasagar, V.; Hadzi-Pavlovic, D.; Whitton, A.; Nicholas, J.; Smith, M.; Burckhardt, R. Effects of adjunctive peer support on perceptions of illness control and understanding in an online psychoeducation program for bipolar disorder: A randomised controlled trial. J. Affect. Disord. 2012, 142, 98–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, E.; Duan, L.; Cohen, H.; Kiger, H.; Pancake, L.; Brekke, J. Integrating behavioral healthcare for individuals with serious mental illness: A randomized controlled trial of a peer health navigator intervention. Schizophr. Res. 2017, 182, 135–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahlke, C.I.; Priebe, S.; Heumann, K.; Daubmann, A.; Wegscheider, K.; Bock, T. Effectiveness of one-to-one peer support for patients with severe mental illness—A randomised controlled trial. Eur. Psychiatry 2017, 42, 103–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, S.; Lamb, D.; Marston, L.; Osborn, D.; Mason, O.; Henderson, C.; Ambler, G.; Milton, A.; Davidson, M.; Christoforou, M.; et al. Peer-supported self-management for people discharged from a mental health crisis team: A randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2018, 392, 409–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maru, M.; Rogers, E.S.; Nicolellis, D.; Legere, L.; Placencio-Castro, M.; Magee, C.; Harbaugh, A.G. Vocational peer support for adults with psychiatric disabilities: Results of a randomized trial. Psychiatr. Rehabil. J. 2021, 44, 327–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, K.; Salzer, M.S.; Solomon, P.; Brusilovskiy, E.; Cousounis, P. Internet peer support for individuals with psychiatric disabilities: A randomized controlled trial. Soc. Sci. Med. 2011, 72, 54–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, D.; Jia, R.; Zhou, X.; Lu, G.; Wu, Z.; Yu, J.; Wang, Z.; Huang, H.; Guo, J.; Chen, C. The effectiveness of peer support on self-efficacy and self-management in people with type 2 diabetes: A meta-analysis. Patient Educ. Couns. 2021, 104, 760–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, E.; Pyle, M.; Machin, K.; Varese, F.; Morrison, A.P. The effects of peer support on empowerment, self-efficacy, and internalized stigma: A narrative synthesis and meta-analysis. Stigma Health 2019, 4, 337–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirkis, J.; Burgess, P.; Hardy, J.; Harris, M.; Slade, T.; Johnston, A. Who cares? A profile of people who care for relatives with a mental disorder. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 2010, 44, 929–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wingate, L.; Graffy, J.; Holman, D.; Simmons, D. Can peer support be cost saving? An economic evaluation of RAPSID: A randomized controlled trial of peer support in diabetes compared to usual care alone in East of England communities. BMJ Open Diabetes Res. Care 2017, 5, e000328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, L.D.; Vasquez, D.; Wolf, J.; Robison, J.; Hartigan, L.; Hollman, R. Supporting peer support workers and their supervisors: Cluster-randomized trial evaluating a systems-level intervention. Psychiatr. Serv. 2024, 50, appips20230112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cook, J.A.; Steigman, P.; Pickett, S.; Diehl, S.; Fox, A.; Shipley, P.; Burke-Miller, J.K. Randomized controlled trial of peer-led recovery education using building recovery of individual dreams and goals through education and support (BRIDGES). Schizophr. Res. 2012, 136, 36–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pickett, S.A.; Diehl, S.M.; Steigman, P.J.; Prater, J.D.; Fox, A.; Shipley, P.; Cook, J.A. Consumer empowerment and self-advocacy outcomes in a randomized study of peer-led education. Commun. Ment. Health J. 2012, 48, 420–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Gestel-Timmermans, H.; Brouwers, E.P.; van Assen, M.A.; van Nieuwenhuizen, C. Effects of a peer-run course on recovery from serious mental illness: A randomized controlled trial. Psychiatr. Serv. 2012, 63, 54–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jonikas, J.A.; Grey, D.D.; Copeland, M.E.; Razzano, L.A.; Hamilton, M.M.; Floyd, C.B.; Hudson, W.B.; Cook, J.A. Improving propensity for patient self-advocacy through wellness recovery action planning: Results of a randomized controlled trial. Commun. Ment. Health J. 2013, 49, 260–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russinova, Z.; Rogers, E.S.; Gagne, C.; Bloch, P.; Drake, K.M.; Mueser, K.T. A randomized controlled trial of a peer-run antistigma. Photovoice Interv. Psychiatr. Serv. 2014, 65, 242–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ben-Zeev, D.; Brian, R.M.; Jonathan, G.; Razzano, L.; Pashka, N.; Carpenter-Song, E.; Drake, R.E.; Scherer, E.A. Mobile health (mHealth) versus clinic-based group intervention for people with serious mental illness: A randomized controlled trial. Psychiatr. Serv. 2018, 69, 978–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, S.; Choi, H. A systematic review on peer support services related to the mental health services utilization for people with severe mental illness. J. Korean Acad. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2020, 29, 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Trials/ Study Design | Country- Recruitment | Diagnosis | Mean Age (Year) | Female (%) | No. of Participants (Intervention/ Control) | Peer Support Intervention | Comparison | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type | Provider Supervision | Duration/ No. of Sessions | Min/Session | |||||||

| Sells 2008 [36] RCT | The USA— community | 61% SPR 70% Multiple | 42 | 38.7 | 68/69 | One-on-one offline (no manual) | Supervised | 12 mos. /N/A | N/A | TAU |

| Cook 2011 [48] RCT | The USA— community | 21% SPR 38% BPD 25% DD | 46 | 65.9 | 276/279 | Group offline (manual) | Unknown | 8 wks/8 | 2.5 h | TAU |

| Segal 2011 [24] RCT | The USA— community | 100% SPR | 39 | 53.9 | 86/53 | One-on-one (manual) | No | 8 mos /N/A | N/A | TAU |

| Kaplan 2011 [42] RCT | The USA— community | 100% SPR | 47 | 65.7 | 200/100 | One-on-one online (no manual) | No | 12 mos/ N/A | N/A | TAU |

| Pickett 2012 [49] RCT | The USA— community | 39% SPR 40% BPD | 43 | 55.6 | 212/216 | Group (manual) | Unknown | 8 wks/ N/A | 2.5 h | TAU |

| Gestel-Timmermans 2012 [50] RCT | The Netherlands— community | 33% SPR | 44 | 66.1 | 168/165 | Group offline (manual) | No | 12 wks/ weekly | 2 h | TAU |

| Proudfoot 2012 [37] RCT | Australia— community | 100% BPD | 18–75 | 69.8 | 139/134/134 | One-on-one online (manual) | No | 8 wks/ N/A | N/A | TAU |

| Chinman 2013 [21] RCT | The USA— community | 100% SMI | 53 | 25.5 | 149/133 | One-on-one offline (manual) | Supervised weekly | 12 mos/ 8 | 2.5 h | TAU |

| Jonikas 2013 [51] RCT | The USA— community | 21% SPR 38% BPD 25% DD | older than 18 | 65.9 | 276/279 | Individual and group offline (manual) | Unknown | 2 mos/ weekly | 2.5 h | TAU |

| Russinova 2014 [52] RCT | The USA— community | 34% SPR 33% BPD 26% DD | older than 18 | 68.3 | 40/42 | Group offline (manual) | No | 10 wks/ N/A | 90 min | TAU |

| Salzer 2016 [23] RCT | The USA— community | 100% SPR | 49 | 46.5 | 50/49 | One-on-one offline (manual) | Supervised | 12 mos/ N/A | N/A | TAU |

| Kelly 2017 [38] RCT | The USA— community | 37% SPR 19.2% BPD 39% DD | 46 | 53.6 | 76/75 | One-on-one offline (manual) | Supervised weekly | 6 mos/ N/A | N/A | TAU |

| Mahlke 2017 [39] RCT | Germany— four hospitals | 28% SPR 15% BPD 25% DD | 42 | 57.4 | 114/102 | One-on- one offline (manual) | Supervised bi-weekly | 12 mos/ 1 meeting per week | 1 h | TAU |

| Ben-Zeev 2018 [53] RCT | The USA— community | 49% SPR 28% BPD 23% MDD | 49 | 41.1% | 163 (81/82) | One-on-one mobile (manual) | No | 3 mos/ weekly | N/A | TAU |

| Johnson 2018 [40] RCT | The UK— community | 14% SPR 12% BPD 23% DD | 40 | 60.1% | 441 (220/218) | One-on-one offline (manual) | Supervised bi-weekly | 18 mos/ 10 | 1 h | TAU |

| Maru 2021 [41] RCT | The USA— community | 33% SPR 29% BPD 15% DD | 45 | 51.2% | 166 (83/83) | One-on-one and group offline (manual) | Supervised weekly | 12 mos/ 23 | N/A | TAU |

| Trials | Outcomes | Assessments | Measure by Time Point | Result-Key Finding |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sells 2008 [36] | (1) Relationship (2) Addiction severity (3) Quality of life | (1) Barrett-Lennard Relationship Inventory (BLRI) (2) Addiction Severity Index (ASI) (3) Quality of Life Inventory– Brief Version (QOLI-B) | (1) Post-intervention (6 mos) (2) Post-intervention (12 mos) | Participants with peers reported a better therapeutic relationship than the control group at the 6-mo follow-up. |

| Cook 2011 [48] | (1) Psychiatric symptom (2) Hopefulness (3) Quality of life | (1) Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI) (2) Hope Scale (HP) (3) World Health Organization Quality of Life Brief Instrument (WHOQOL-BREF) | (1) Baseline (2) Post-intervention (8 weeks) (3) Post-intervention (6 mos) | Significantly improved increases in overall clinical symptoms, hopefulness, and quality of life over time compared with the control group |

| Segal 2011 [24] | (1) Empowerment (2) Self-Efficacy (3) Social integration (4) Psychiatric symptoms (5) Hopefulness | (1) Empowerment scale (2) Self-Efficacy Scale (3) Independent Social Integration Scale (ISIS) (4) Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) (5) Hopelessness Scale | (1) Baseline (2) Post-intervention (8 mos) | Neither psychiatric symptoms nor hopelessness differed by service condition across time. |

| Kaplan 2011 [42] | (1) Recovery (2) Quality of life (3) Empowerment (4) Medical & social support (5) Psychiatric symptoms | (1) Recovery Assessment Scale (RAS) (2) Quality of Life (3) Empowerment Scale (4) Medical Outcomes Study (MOS) (5) Hopkins Symptoms Checklist (HSCL) | (1) Baseline (2) Post-intervention (4 mos) (3) Post-intervention (12 mos) | No differences between conditions on the main outcomes |

| Pickett 2012 [49] | (1) Attendance (2) Empowerment (3) Self-efficacy | (1) Attendance Rates (2) 28-item Empowerment Scale (3) Patients Self-advocacy Scale (PSAS) | (1) Baseline (2) Post-intervention (8 wks) (3) Post-intervention (6 mos) | Significant increases in overall empowerment, empowerment-self-esteem, self-advocacy, and assertiveness, with these outcomes improved over time |

| Gestel-Timmermans 2012 [50] | (1) Hopefulness (2) Quality of life (3) Self-efficacy (4) Empowerment (5) Loneliness | (1) Health Hope Index (HHI) (2) Manchester Short Assessment of Quality of Life (MANSA) (3) Mental Health Confidence Scale (MHCS) (4) Dutch Empowerment Scale (5) Loneliness Scale | (1) Baseline (2) Post-intervention (3 mos) (3) Post-intervention (6 mos) | A significant and positive effect on empowerment, hope, and self-efficacy beliefs but not on quality of life and loneliness; effects of the intervention persisted three months after participants completed the course |

| Proudfoot 2012 [37] | (1) Perceptions (2) Secondary outcomes: anxiety, depression, work and social adjustment, self-esteem, life satisfaction, health focus of control, stigma | (1) Brief Illness Perception Questionnaire (Brief IPQ) (2) Goldberg Anxiety and Depression Scale (GADS) (3) Work and Social Adjustment Scale (WSAS) (4) Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS) (5) Multidimensional Health Locus of Control (MHLC) (6) Mood Monitoring | (1) Baseline (2) Post-intervention (8 weeks) (3) Post-intervention (3 mos) (4) Post-intervention (6 mos) | Increased perceptions of control, decreased perceptions of stigmatization, and improvements in levels of anxiety and depression but no differences between groups on outcomes; adherence to the treatment program was significantly higher than that in the control group |

| Chinman 2013 [21] | (1) Recovery (2) Quality of life (3) Activation (health self-management efficacy (4) Interpersonal relations (5) Psychiatric symptoms | (1) Recovery Self-Assessment (RSA) (2) Mental Health Recovery Measure (MHRM) (3) Quality of Life Instrument Brief Version (QOLI) (4) Patient Activation Measure (PAM) (5) BASIS-R Scales | (1) Baseline (2) Post-intervention (12 mos) | Improved significantly more than control group, but with no significant differences |

| Jonikas 2013 [51] | (1) Patient self-advocacy (2) Hopefulness (3) Quality of life (4) Psychiatric symptoms | (1) Patient-Self-Advocacy Scale (PSAS) (2) Hope Scale (HS) (3) Quality of Life Brief Instrument (WHOQOLBREF) (4) Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI) | (1) Baseline (before 6 wks) (2) Post-intervention (6 weeks) (3) Post-intervention (6 mos) | Significantly more engaged in self-advocacy with service providers compared with the control group |

| Russinova 2014 [52] | (1) Stigma (2) Self-efficacy (3) Recovery (4) Depression | (1) Internalized Stigma of Mental Illness Scale (2) Approaches to Coping With Stigma Scales (3) Personal Growth and Recovery Scale (PGRS) (4) Empowerment Scale (5) Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) (6) Self-Efficacy Scale | (1) Baseline (2) Post-intervention (10 wks) (3) Post-intervention (3 mos) | Significantly reduced self-stigma, greater use of proactive coping with community activism, and perceived recovery and growth |

| Slazer 2016 [23] | (1) Community Participation (2) Recovery (3) Quality of life (4) Empowerment (5) Working alliance | (1) Temple University Community Participation Measure (2) Recovery Assessment Scale (RAS) (3) Lehman’s Quality of Life (4) Empowerment Scale (5) Working Alliance Measure | (1) Baseline (2) Post-intervention (6 mos) (3) Post-intervention (12 mos) | No differences between groups in outcomes |

| Kelly 2017 [38] | (1) Health service (2) Satisfaction (3) Self-management confidence (4) Health issues | (1) Health service utilization (2) Satisfaction with primary care provider (3) Self-management attitudes and behaviors (4) Routine health screening (5) Health status (medical diagnosis, pain) | (1) Baseline (2) Post-intervention (6 mos) | Significant improvements in the therapeutic relationship, increased preference for primary care clinics, and improved reductions in pain compared with the control group but increased confidence in consumer self-management of healthcare and decreased preference for emergencies were not significantly higher than the control group |

| Mahlke 2017 [39] | (1) General self-efficacy scale (GSE) (2) Quality of life (3) Clinician ratings (4) Service use | (1) General Self-Efficacy Scale (GSE) (2) EQ5D (EuroQoL-D5) (3) GAF (Global Assessment Functioning), CGI (Clinical Global Impression) (4) MSLQ-R (Motivated Strategies for Learning Questionnaire) | (1) Baseline (2) Post-intervention (6 mos) (3) Post-intervention (12 mos) | Significantly higher scores of self-efficacy at the 6-month follow-up compared with the control group |

| Ben-Zeev 2018 [53] | (1) Participant (2) Satisfaction (3) Clinical outcomes | (1) Engagement Rate (2) Satisfaction Rate (3) Symptom Checklist–9 (SCL-9) (4) Beck Depression Inventory-2 (BDI-2) (5) Psychotic Symptom Rating Scales (PSYRATS) (6) Recovery Assessment Scale (RAS) (7) Quality of Life (QoL) | (1) Baseline (2) Post-intervention (3 mos) (3) Post-intervention (6 mos) | Significant improvements in recovery were seen for the control group post-treatment, and significant improvements in recovery and quality of life were seen for the intervention group at 6 mos. Clinical outcomes significantly improved in both groups but did not differ. |

| Johnson 2018 [40] | Acute care readmission | (1) Client Satisfaction Questionnaire (2) Illness Management and Recovery Scale (3) University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) Loneliness Scale (4) Lubben Social Network Scale | (1) Baseline (2) Post-intervention (4 mos) (3) Post-intervention (18 mos) | Readmission to acute care within 1 year was significantly lower in the intervention group than in the control group. |

| Maru 2021 [41] | (1) Vocational and prevocational activity (2) Quality of life (3) Work hope (4) Work readiness (5) Working alliance (6) Participant rate | (1) Vocational and Prevocational Activity (2) Quality of Life (3) Work Hope Scale (4) Work Readiness Scale (5) Working Alliance Inventory-Short Form (6) Participant data of session | (1) Baseline (2) Post-intervention (6 mos) (3) Post-intervention (12 mos) | There were some differences in vocational preparation areas and vocational activities between the intervention and control groups. Some aspects of quality of life and career aspirations improved in the intervention group compared with the control group. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lee, S.-N.; Yu, H.-J. Effectiveness of Peer Support Programs for Severe Mental Illness: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Healthcare 2024, 12, 1179. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12121179

Lee S-N, Yu H-J. Effectiveness of Peer Support Programs for Severe Mental Illness: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Healthcare. 2024; 12(12):1179. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12121179

Chicago/Turabian StyleLee, Sung-Nam, and Hea-Jin Yu. 2024. "Effectiveness of Peer Support Programs for Severe Mental Illness: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis" Healthcare 12, no. 12: 1179. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12121179

APA StyleLee, S.-N., & Yu, H.-J. (2024). Effectiveness of Peer Support Programs for Severe Mental Illness: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Healthcare, 12(12), 1179. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12121179