Towards the Improvement of Patient Experience Evaluation Items for Patient-Centered Care in Head and Neck Cancer: A Qualitative Comparative Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Study Background

1.2. Study Aim and Research Questions

- (1)

- What aspects of PE should be comprehensively considered to improve patients’ QoL?;

- (2)

- What aspects of PE do current HNC measures address? Also, what aspects are lacking?;

- (3)

- What are users’ needs related to HNC treatment, and what new PE evaluation items can be added through this?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Phase 1: A Systematic Literature Review of PE Factors

2.2. Phase 2: Analysis of Current QoL Evaluation Tools

2.3. Phase 3: Analysis of HNC Patient Needs

2.4. Phase 4: Suggestion of HNC PE Evaluation Items through Validation

3. Results

3.1. Phase 1: Identification of Factors Influencing PE Improvement

3.2. Phase 2: Analysis of Current HNC PE Evaluation Tools

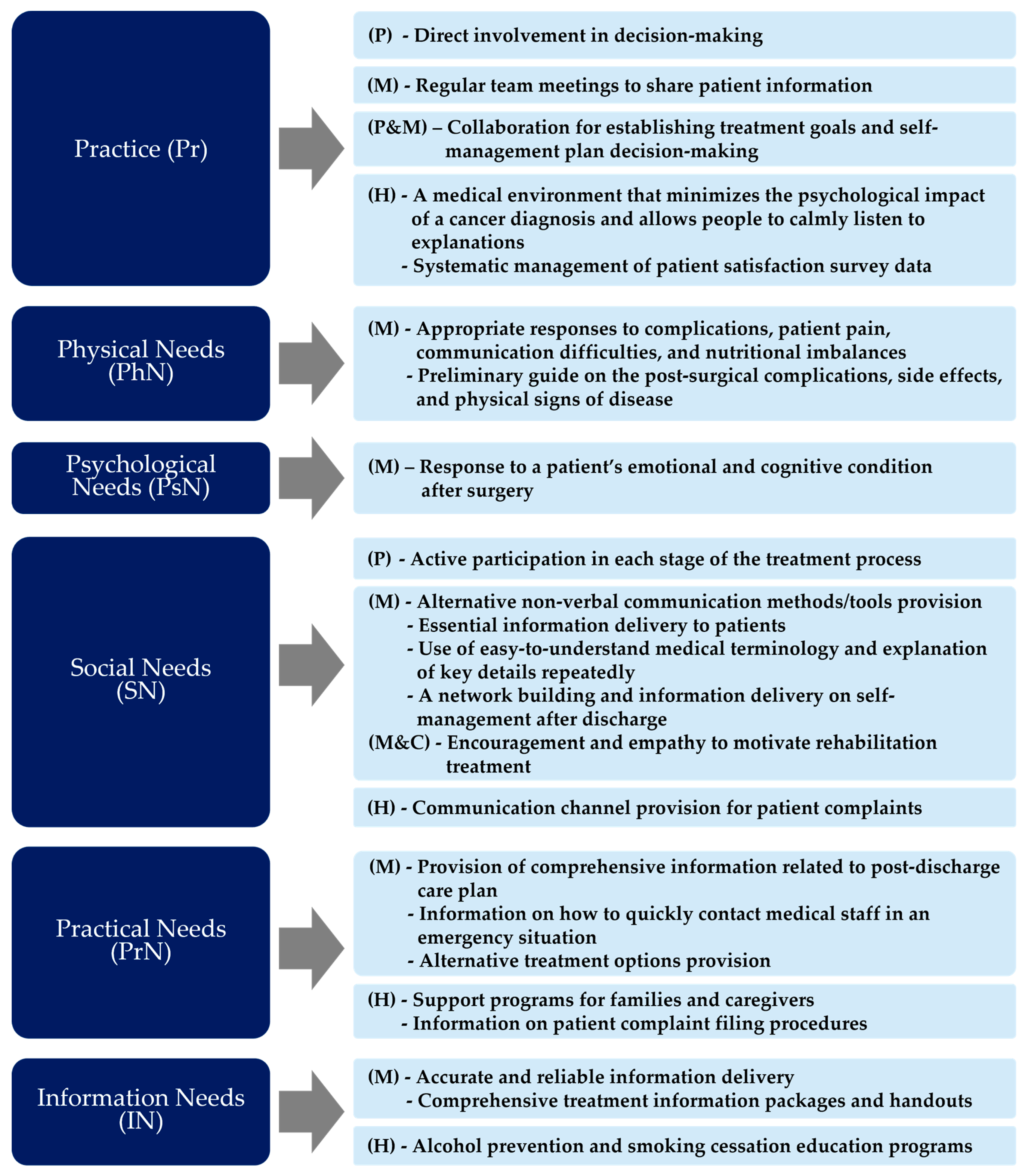

3.3. Phase 3: Identification of Insights for Potential Items Based on Patients with HNC Needs

3.4. Validation

4. Discussion

4.1. Summary

4.2. Implications and Study Limitation

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, X.S.; Gottumukkala, V. Patient-reported outcomes: Is this the missing link in patient-centered perioperative care? Best Pract. Res. Clin. Anaesthesiol. 2021, 35, 565–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, E.; Mavondo, F.; Fisher, J. Patient feedback to improve quality of patient-centred care in public hospitals: A systematic review of the evidence. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2020, 20, 530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taberna, M.; Gil Moncayo, F.; Jané-Salas, E.; Antonio, M.; Arribas, L.; Vilajosana, E.; Peralvez Torres, E.; Mesía, R. The multidisciplinary team (MDT) approach and quality of care. Front. Oncol. 2020, 10, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, B.; James, P.; Vijayasiri, G.; Li, Y.; Bozaan, D.; Okammor, N.; Hendee, K.; Jenq, G. Patient perspectives on care transitions from hospital to home. JAMA Netw. Open 2022, 5, e2210774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakeel, S.; Tung, J.; Rahal, R.; Finley, C. Evaluation of factors associated with unmet needs in adult cancer survivors in Canada. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e200506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendez, A.; Seikaly, H.; Eurich, D.; Dzioba, A.; Aalto, D.; Osswald, M.; Harris, J.R.; O’Connell, D.A.; Lazarus, C.; Urken, M.; et al. Development of a Patient-Centered Functional Outcomes Questionnaire in Head and Neck Cancer. JAMA Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2020, 146, 437–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grønkjær, L.L.; Lauridsen, M.M. Quality of life and unmet needs in patients with chronic liver disease: A mixed-method systematic review. JHEP Rep. 2021, 3, 100370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triberti, S.; Savioni, L.; Sebri, V.; Pravettoni, G. eHealth for improving quality of life in breast cancer patients: A systematic review. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2019, 74, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savioni, L.; Triberti, S.; Durosini, I.; Sebri, V.; Pravettoni, G. Cancer patients’ participation and commitment to psychological interventions: A scoping review. Psychol. Health 2022, 37, 1022–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grassi, L.; Caruso, R.; Da Ronch, C.; Härter, M.; Schulz, H.; Volkert, J.; Dehoust, M.; Sehner, S.; Suling, A.; Wegscheider, K.; et al. Quality of life, level of functioning, and its relationship with mental and physical disorders in the elderly: Results from the MentDis_ICF65+ study. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2020, 18, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveri, S.; Arnaboldi, P.; Pizzoli, S.F.; Faccio, F.; Giudice, A.V.; Sangalli, C.; Luini, A.; Pravettoni, G. PTSD symptom clusters associated with short-and long-term adjustment in early diagnosed breast cancer patients. Ecancermedicalscience 2019, 13, 917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauer, C.; Weis, J.; Faller, H.; Junne, F.; Hönig, K.; Bergelt, C.; Hornemann, B.; Stein, B.; Teufel, M.; Goerling, U.; et al. Impact of social support on psychosocial symptoms and quality of life in cancer patients: Results of a multilevel model approach from a longitudinal multicenter study. Acta Oncol. 2019, 58, 1298–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebri, V.; Mazzoni, D.; Triberti, S.; Pravettoni, G. The impact of unsupportive social support on the injured self in breast cancer patients. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 722211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takes, R.P.; Halmos, G.B.; Ridge, J.A.; Bossi, P.; Merkx, M.A.; Rinaldo, A.; Sanabria, A.; Smeele, L.E.; Mäkitie, A.A.; Ferlito, A. Value and quality of care in head and neck oncology. Curr. Oncol. Rep. 2020, 22, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Araújo Gomes, E.P.A.; Aranha, A.M.F.; Borges, A.H.; Volpato, L.E.R. Head and neck cancer patients’ quality of life: Analysis of three instruments. J. Dent. 2020, 21, 31. [Google Scholar]

- Riechelmann, H.; Dejaco, D.; Steinbichler, T.B.; Lettenbichler-Haug, A.; Anegg, M.; Ganswindt, U.; Gamerith, G.; Riedl, D. Functional outcomes in head and neck cancer patients. Cancers 2022, 14, 2135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koo, Y.; Kim, E.; Jo, Y.; Nam, I. Patient Experience Factors and Implications for Improvement Based on the Treatment Journey of Patients with Head and Neck Cancer. Cancers 2023, 15, 2265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.-J.; Koo, Y.-R.; Nam, I.-C. Patients and Healthcare Providers’ Perspectives on Patient Experience Factors and a Model of Patient-Centered Care Communication: A Systematic Review. Healthcare 2024, 12, 1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langley, P.C.; McKenna, S.P. Fundamental Measurement: The Need Fulfilment Quality of Life (N-QOL) Measure. Innov. Pharm. 2021, 12, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bissenbakker, K.; Møller, A.; Brodersen, J.B.; Jønsson, A.B.R. Conceptualisation of a measurement framework for Needs-based Quality of Life among patients with multimorbidity. J. Patient-Rep. Outcomes 2022, 6, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, R.M.; Hays, R.D. Health-related quality of life measurement in public health. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2022, 43, 355–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDowell, L.; Rischin, D.; Gough, K.; Henson, C. Health-related quality of life, psychosocial distress and unmet needs in older patients with head and neck cancer. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 834068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The patient Satisfaction Questionnaire Short Form (PSQ-18). Available online: https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/papers/2006/P7865.pdf (accessed on 27 December 2023).

- 36-Item Short Form Survey (SF-36). Available online: https://www.rand.org/health-care/surveys_tools/mos/36-item-short-form.html (accessed on 27 December 2023).

- CAHPS Cancer Care Survey. Available online: https://www.ahrq.gov/cahps/surveys-guidance/cancer/index.html (accessed on 27 December 2023).

- Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy—Head & Neck (FACT-HN) (Version 4). Available online: https://www.facit.org/measures/FACT-HN (accessed on 27 December 2023).

- University of Washington Quality of Life Questionnaire (UW-QOL). Available online: http://www.hancsupport.com/sites/default/files/assets/pages/UW-QOL-update_2012.pdf (accessed on 27 December 2023).

- EORTC QLQ-C30 (Version 3). Available online: https://www.eortc.org/app/uploads/sites/2/2018/08/Specimen-QLQ-C30-English.pdf (accessed on 27 December 2023).

- Head & Neck Cancer (Update of QLQ-H&N35). Available online: https://qol.eortc.org/questionnaire/qlq-hn43/ (accessed on 27 December 2023).

- Graneheim, U.H.; Lundman, B. Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: Concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Educ. Today 2004, 24, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsang, S.; Royse, C.F.; Terkawi, A.S. Guidelines for developing, translating, and validating a questionnaire in perioperative and pain medicine. Saudi J. Anaesth. 2017, 11 (Suppl. S1), S80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinmann, G.; Delnoij, D.; Van De Bovenkamp, H.; Groote, R.; Ahaus, K. Expert consensus on moving towards a value-based healthcare system in the Netherlands: A Delphi study. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e043367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| User Research Method | Users Involved (Gender, Age) | Date |

|---|---|---|

| In-depth Interview | Resident (female, 31) | 27 August 2021 |

| Specialist (male, 45) | 10 September 2021 | |

| Resident (female, 31) | 10 September 2021 | |

| Patient (male, 65)/Caregiver (female, 39) | 27 August 2021 | |

| Patient (male, 56)/Caregiver (female, 54)/Specialist (male, 45) | 27 August 2021 | |

| Patient (male, 70)/Caregiver (female, 68) | 27 August 2021 | |

| Patient (male, 56)/Caregiver (female, 60)/Specialist (male, 45) | 1 October 2021 | |

| Patient (male, 70)/Caregiver (female, 68) | 7 October 2021 | |

| Patient (female, 74)/Specialist (male, 45) | 15 October 2021 | |

| Observation | Patient (male, 65)/Caregiver (male, 39)/Specialist (male, 45) | 27 August 2021 |

| Patient (male, 48)/Caregiver (male, 49)/Specialist (male, 45) | 27 August 2021 | |

| Patient (male, 70)/Caregiver (female, 68)/Resident (female, 31) | 10 September 2021 | |

| Patient (male, 56)/Caregiver (female, 60)/Specialist (male, 45) | 5 October 2021 | |

| Patient (female, 74)/Specialist (male, 45) | 15 October 2021 |

| No. | Criteria | Items for Validation |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Clarity of meaning | The factors described for each category were straightforward to understand |

| 2 | Diversity of stakeholder perspectives | The resulting factors covered various aspects of PE categories |

| 3 | Availability of use in hospital settings | The suggested factors can be used to evaluate QoL of HNC patients in the future |

| 4 | Importance as an evaluation indicator | The identified factors can be considered important regarding the QoL of HNC patients |

| 5 | Ethics that does not infringe on individual privacy | Some of the factors violate privacy issues |

| (A) | |||||

| Subcategory | Phase 1 | Phase 2 | Phase 3 | Initial Synthesis (Stakeholders) † | Newly Derived Items (Stakeholders) † |

| [Pr1] coordination | [a] scheduled team meetings [b] structured team communications focused on individual patient care | [c] review and discussion of prescription drugs | [d] consistent treatment and information delivery through effective communication between departments |

| [Pr1-1] regular team meetings to share patient information (a, d) (M) |

| [Pr2] skill | [a] reduce repetitive assessments by multiple staff [b] a dedicated space for diagnosis [c] written and verbal discharge information to patients | - | [d] comprehensive guidance on essential examination methods and procedures according to the treatment stage |

| [Pr2-1] a dedicated space for cancer diagnosis (b) (M, P) [Pr2-2] the treatment information provided in written and verbal forms (c, d) (M, P) |

| [Pr3] care plan | [a] the practice’s collaboration with the patient/caregivers for treatment goals and self-management planning [b] the practice’s coordination with healthcare providers/specialists/consultants for pertinent demographic and clinical data | [c] adequate discussion of treatment after cancer surgery decision | - |

| [Pr3-1] patients/medical staff/caregivers collaborating on treatment goals and self-management plans (a, c) (M, P) |

| [Pr4] organization | [a] reliable complaints data sets to govern care quality, safety, and patient centricity [b] leadership committed and engaged to unify and sustain the organization in a joint mission [c] a vision clearly and constantly communicated to every member of the organization | - | - |

| [Pr4-1] patient complaint data being systematically managed to ensure quality care, safety, and patient-centeredness (a) (H) |

| [Pr5] QI | [a] the opportunity to ask questions about recommended treatment [b] the doctors’ or nurses’ time spent with patients [c] patient involvement in decisions about their care [d] the practice’s ability to set goals, analyze, and act to improve performance on immunization rates, preventive care measures, resource use, and care coordination measures [e] structure and support provided by the organization for identifying and implementing QI [f] monitoring QI as part of staff performance assessment | [g] encouragement of medical staff to ask questions after cancer surgery decisions, before and after visits, if necessary [h] careful listening to and showing of respect and courtesy to the patient | - |

| [Pr5-1] the time per day doctors/nurses spend with patients (face-to-face interaction) (b) (M, P) [Pr5-2] the patient being directly involved in treatment decision-making (e) (M, P) [Pr5-3] practice plan; analysis of the implementation and rates of immunization, preventive care, resource use, and care coordination measures adequate for QI analysis and implementation (d) (H) |

| [Pr6] management | [a] the practice’s ability to proactively identify patient populations for periodic care needs [b] collaboration and team management [c] monitoring the impact of specific interventions and change strategies [d] scheduling meetings to discuss PE results, plan improvements, and triangulating multiple data sources to understand feedback | [e] assessment of the adequacy of the details of the information provided to the patient, timing of information provided, amount of verbally transmitted information, amount of written information provided, information provided to family/caregivers, and information provided to the patient | - |

| [Pr6-1] discussion of PE results and improvement plans and verification of data between the teams (b, d) (M, H) |

| (B) | |||||

| Subcategory | Phase 1 | Phase 2 | Phase 3 | Initial Synthesis (Stakeholders) † | Newly Derived Factors (Stakeholders) † |

| [PhN1] physical supports | [a] physical functioning, role functioning, arm symptoms, body image, and pain [b] physical comfort, freedom from pain, cognitive symptoms, and fatigue [c] treatment-related side effects; fertility concerns [d] physical manifestations of the disease (nausea and fatigue) | [e] pain, soreness, swallowing (mouth, chin, neck, shoulders) [f] swallowing food (liquids, solid foods, pureed formula) [g] discomfort (teeth, tooth loss, mouth opening, smell, taste, cough, hoarseness, appearance, eating (chewing), arm movement, itchy and dry skin, dry mouth, and sticky saliva) [h] pain due to cancer or cancer surgery [i] counseling on pain due to cancer or cancer surgery | [j] medical staff’s treatment method to minimize side effects [k] preliminary guidance on the possibility of external disorders and side effects after surgery [l] response and treatment of physical symptoms (communication difficulties, nutritional imbalance) that may occur during the recovery process after surgery | [PhN1-1] the pain level, symptoms, and dysfunction (physical functioning, role functioning, arm symptoms, body image, pain) (a, e, f, g, h) (P)

| [PhN1-1] response/treatment being appropriately performed to minimize side effects and relieve pain (b, j) (P) [PhN1-2] preliminary guidance on the possibility of external disorders, complications after surgery, side effects from treatment, and physical signs of illness (c, d, k) (P) [PhN1-3] the medical team appropriately responding to and treating possible communication difficulties and nutritional imbalances during the recovery period after surgery (l) (P) |

| (C) | |||||

| Subcategory | Phase 1 | Phase 2 | Phase 3 | Initial Synthesis (Stakeholders) † | Newly Derived Factors (Stakeholders) † |

| [PsN1] Psychological support | [a] emotion, concentration, remembering, and fatigue [b] introduction of hourly proactive nursing rounds/weekly senior executive rounds [c] telephone contact to nurses regarding health concerns and clinical leads to review care information flow [d] ability to cope [e] social/family relationships [f] reassurance [g] emotional health | [h] pain advice and help [i] counseling for emotional problems such as anxiety or depression related to cancer or cancer surgery [j] suffering from emotional problems such as anxiety or depression [k] advice and help with emotional problems [l] feeling physically less attractive because of an illness or treatment [m] worries about cancer, anxiety, and retaining a hopeful attitude toward treatment | [n] medical staff’s empathy for the psychological aspects of patients/caregivers [o] emotional support from medical staff to relieve patients’ anxiety and motivate them to recover [p] appropriate response to the anxiety felt by patients/caregivers |

| [PsN1-1] the patient’s emotional health index of concentration, remembering, fatigue, and loss of confidence (a, g, l) (P) [PsN1-2] information regarding the nurse’s round time/schedule being provided to the patient (b) (M, P) [PsN1-3] empathy and motivation among medical staff for the psychological aspects of patients/caregivers (n, o) (M, P) |

| (D) | |||||

| Subcategory | Phase 1 | Phase 2 | Phase 3 | Initial Synthesis (Stakeholders) † | Newly Derived Factors (Stakeholders) † |

| [SN1] Communication | [a] family life; social encounters [b] involvement of patients and families at multiple levels in the care process [c] communication with caregivers [d] use of slogans and acronyms to promote communication [e] interpersonal skills training for staff [f] setting of behavioral standards for staff [g] use of filmed PE interviews as communication education | [h] problems with communication with medical staff, caregivers, and family members [i] inconvenience of phone calls [j] limitations of clarification | [k] use of terms that are easy for elderly patients to understand [l] sufficient and repetitive explanations to help elderly patients understand [m] various communication methods and tools in preparation for cases when verbal communication is difficult |

| [SN1-1] the various communication tools provided in case verbal communication is not possible (m) (M, P) [SN1-2] the necessary information delivered to the patient; and contacting the patient by phone if necessary (i, j) (P) [SN1-3] the terms used that are easy for older patients to understand; explanations given several times to aid understanding (k, l) (M, P) [SN1-4] the patient and family being involved in the care process at multiple levels (b, c, h) (M, P) [SN1-5] the interpersonal skill training conducted for staff; the behavioral standards for staff presented (e, f, g) (M, H) |

| [SN2] support | [a] the practice’s collaboration with the patient/caregivers for treatment goals and self-management planning [b] network support to readjust to living independently post-discharge [c] accessibility improvement for commonly excluded patient groups (complainants burdened by health conditions or language barriers) | [d] provision of service information for home care after discharge [e] interpretation service for foreigners [f] provision of information on patient support groups for patients and caregivers | [g] preliminary information on self-management, such as regular exercise and lifestyle to follow surgery [h] encouragement and consolation of medical staff to motivate rehabilitation treatment [i] comfort and encouragement from people around the patient [j] relief of the burden of treatment costs, such as additional non-coverage costs in case of emergency (medical cost support plan guide) |

| [SN2-1] the practice establishing a network and providing information to support self-management after discharge (b, d, g) (M, P) [SN2-2] accessibility being improved for commonly excluded patient groups (c, e, f) (H, P) [SN2-3] the medical staff and people around them providing encouragement and comfort to motivate rehabilitation treatment (h, i) (M, P) [SN2-4] plans or support being made to reduce the burden of treatment costs (j) (H, P) |

| [SN3] respect | [a] staff encouragement of complaint procedures [b] explaining things to understand [c] listening carefully to patients [d] showing respect to patients for their needs and preferences | [e] easy-to-understand explanation (how easy it is to understand the information) [f] listening carefully and respectfully | [g] communication and efforts of medical staff to build bond and trust between patient and medical staff [h] maintaining a positive attitude based on objective facts rather than excessive hope [i] use of terms that are easy for patients to understand [j] a communication window where patients can express their feelings to medical staff |

| [SN3-1] communication channels being provided for patients and caregivers to file complaints (a, j) (H, P) [SN3-2] the medical team maintaining a positive attitude (h) (M, P) |

| [SN4] responsive-ness | [a] comprehensive and bespoke responding to improve complainant satisfaction [b] spending enough time with patients | [c] medical staff devote enough time to patients | - |

| |

| (E) | |||||

| Subcategory | Phase 1 | Phase 2 | Phase 3 | Initial Synthesis (Stakeholders) † | Final Factors (Stakeholders) † |

| [PrN1] Access to care | [a] assistance in affording and access to care services not covered by insurance or transportation [b] health insurance coverage [c] assistance with transportation to appointments driving, offering refreshments, navigation through the center, and parking [d] finance, parking cost, and information about post-discharge care [e] medical staff available when needing care [f] process for providing appointments and alternative types of clinical encounters [g] easy access to information that outlines procedures involved | [h] quick and convenient booking process [i] calling immediately if specific symptoms or side effects occur [j] instructions on how to contact us after regular office hours [k] sharing cancer diagnosis results [l] ordering blood tests, X-rays, and other tests [m] follow-up for the explanation of test results | [n] minimization of wait times for surgery and examinations [o] staff help with guidance and reservation process [p] the location of the hospital closest to the patient’s home (accessibility utilizing transportation) |

| [PrN1-1] assistance with health insurance coverage, finance, and parking costs (a, b, d) (H, P) [PrN1-2] assistance with transportation to appointments driving, offering refreshments, navigation through the center, and parking (c) (H, P) [PrN1-3] information provided about post-discharge care and procedures involved (d, g, k, l, m) (M, P) [PrN1-4] medical staff being available when the patients need care (e, i, j) (P) [PrN1-5] the doctor offering alternative types of clinical options (f, h, o) (M, P) [PrN1-6] minimization of wait times for surgery and examinations (n) (H, P) |

| [PrN2] environment | [a] care for the caregivers through a supportive work environment [b] floor coverings to reduce noise [c] creation of family rooms [d] quiet spaces [e] signposting to complaint procedures to prevent patients from filing a complaint | [f] noise management for conversation | [g] pleasant hospital environment |

| [PrN2-1] family rooms and care for the caregivers being provided through a supportive work environment (a, c) (H, P) [PrN2-2] reduction of noise and provision of a quiet space (b, d, f) (H, P) [PrN2-3] signposting of complaint procedures to prevent patients from filing a complaint (e) (H, P) |

| (F) | |||||

| Subcategory | Phase 1 | Phase 2 | Phase 3 | Initial Synthesis (Stakeholders) † | Newly Derived Factors (Stakeholders) † |

| [IN1] Information & knowledge | [a] more information for being involved, decision-making, or planning future care [b] access to individual information | [c] provision of sufficient information (whether there is a conflict of medications due to treatment; symptoms that can be felt after treatment; effect of treatment on workability, financial support, and future additional treatment; effect of treatment on appearance; expected time to recover; treatment impact on life; information on patient support organizations) | [d] prompt and continuous updates on postoperative progress [e] comprehensive information about the entire treatment process [f] delivery of additional information, such as the cause of cancer [g] information on care plans after discharge, self-management methods, and precautions [h] acquiring accurate and reliable information about HNC |

| [IN1-1] access to individual information for prompt and continuous updates on postoperative progress (b, d) (M, P) [IN1-2] acquisition of accurate and reliable information about HNC (h) (P) |

| [IN2] education | [a] information pack and handouts on treatment options, care navigation, and discharge processes to patients/families | - | [b] educational materials that can systematically and continuously continue rehabilitation training after treatment [c] preventive drinking and smoking cessation education program [d] provision of educational methods and materials for self-management after discharge |

| [IN2-1] information packages and handouts provided on treatment options, discharge procedures, and rehabilitation (a, b, d) (M, P) [IN2-2] preventive drinking and smoking cessation education programs provided (c) (H, P) |

| Category | Round 1 (n = 39) | Between the Rounds | Round 2 (n = 14) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Included | 17 | - | - |

| Excluded | 11 | 3 modified | 2 Included |

| 1 Excluded | |||

| 8 Excluded | - | ||

| Discordance | 11 | 11 modified | 6 Included |

| 2 Excluded | |||

| 3 Discordance | |||

| Summary | 25 Included (17 from Round 1, 8 from Round 2) 11 Excluded (8 from Round 1, 3 from Round 2) 3 Discordance (Round 2) | ||

| No. | Category | Subcategory | PE Factor (Item) | Average Score | Standard Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Practice | Coordination | Organizing regular team meetings to share patient information | 3.45 | 0.56 |

| 2 | Skill | Establishing a medical environment that minimizes the psychological impact of a cancer diagnosis and allows people to calmly listen to explanations | 3.20 | 0.40 | |

| 3 | Providing treatment information to patients through written information in addition to verbal explanations | 3.68 | 0.49 | ||

| 4 | Care Plan | Patients, medical staff, and caregivers working together to establish treatment goals and make decisions about self-management plans | 3.55 | 0.52 | |

| 5 | Organization | Systematic management of patient satisfaction survey (feedback) data to increase patients’ treatment satisfaction (patient experience) | 3.40 | 0.39 | |

| 6 | QI | Patients directly participating in decision making about treatment methods, including surgery, after a cancer diagnosis | 3.45 | 0.57 | |

| 7 | Physical Needs | Physical Supports | Medical staff providing appropriate response and treatment to minimize complications that may occur in patients after surgery and to relieve pain | 3.45 | 0.40 |

| 8 | Advancing the availability of information on post-surgical complications, side effects from treatment, and physical signs of disease | 3.18 | 0.53 | ||

| 9 | Medical staff appropriately responding to and treating communication difficulties and nutritional imbalances that may occur during the recovery period after surgery | 3.65 | 0.45 | ||

| 10 | Psychological Needs | Psychological Supports | Diagnosing and responding to the patient’s mental (emotional and cognitive) condition after surgery, including concentration, memory, fatigue, and loss of confidence | 3.48 | 0.44 |

| 11 | Social Needs | Communication | If a patient is unable to communicate verbally due to a tracheostomy after surgery, providing alternative non-verbal communication methods and tools | 3.4 | 0.64 |

| 12 | Medical staff delivering/guiding essential information to patients | 3.23 | 0.56 | ||

| 13 | Using easy-to-understand medical terminology that is easy for older patients to understand; explaining key details repeatedly to help patients and their caregivers understand | 3.55 | 0.53 | ||

| 14 | Giving consideration to patients and their families to participate as much as possible in each stage of the treatment process (throughout the entire treatment process) | 3.40 | 0.52 | ||

| 15 | Support | Building a network and providing related information to support self-management after discharge | 3.40 | 0.53 | |

| 16 | The medical staff and people around the patient providing encouragement and comfort to maintain and motivate rehabilitation training/treatment to restore the patient’s function | 3.45 | 0.60 | ||

| 17 | Respect | Providing a communication channel through which patients and caregivers can file complaints | 3.40 | 0.74 | |

| 18 | Practical Needs | Access to Care | Providing comprehensive information on outpatient treatment, rehabilitation treatment, and self-management after discharge at the time of patient discharge | 3.33 | 0.79 |

| 19 | Providing guidance on how to quickly contact medical staff in the event of unexpected symptoms or complications | 3.33 | 0.49 | ||

| 20 | Providing alternative treatment options that patients can choose from in addition to the treatment methods suggested to them | 3.08 | 0.51 | ||

| 21 | Environment | Providing support programs for families and caregivers | 3.08 | 0.69 | |

| 22 | Providing information on patient complaint-filing procedures | 3.13 | 0.64 | ||

| 23 | Informational Needs | Information and Knowledge | Obtaining accurate and reliable information about head and neck cancer | 3.15 | 0.63 |

| 24 | Education | Providing a comprehensive information package and handouts regarding treatment options, discharge procedures, and rehabilitation treatment | 3.45 | 0.50 | |

| 25 | Providing alcohol prevention and smoking cessation education programs | 3.23 | 0.61 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kim, E.-J.; Koo, Y.-R.; Nam, I.-C. Towards the Improvement of Patient Experience Evaluation Items for Patient-Centered Care in Head and Neck Cancer: A Qualitative Comparative Study. Healthcare 2024, 12, 1164. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12121164

Kim E-J, Koo Y-R, Nam I-C. Towards the Improvement of Patient Experience Evaluation Items for Patient-Centered Care in Head and Neck Cancer: A Qualitative Comparative Study. Healthcare. 2024; 12(12):1164. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12121164

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, Eun-Jeong, Yoo-Ri Koo, and Inn-Chul Nam. 2024. "Towards the Improvement of Patient Experience Evaluation Items for Patient-Centered Care in Head and Neck Cancer: A Qualitative Comparative Study" Healthcare 12, no. 12: 1164. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12121164

APA StyleKim, E.-J., Koo, Y.-R., & Nam, I.-C. (2024). Towards the Improvement of Patient Experience Evaluation Items for Patient-Centered Care in Head and Neck Cancer: A Qualitative Comparative Study. Healthcare, 12(12), 1164. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12121164