Association of Electronic Cigarette Usage with the Subsequent Initiation of Combustible Cigarette Smoking among Dental Students in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia: A Longitudinal Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

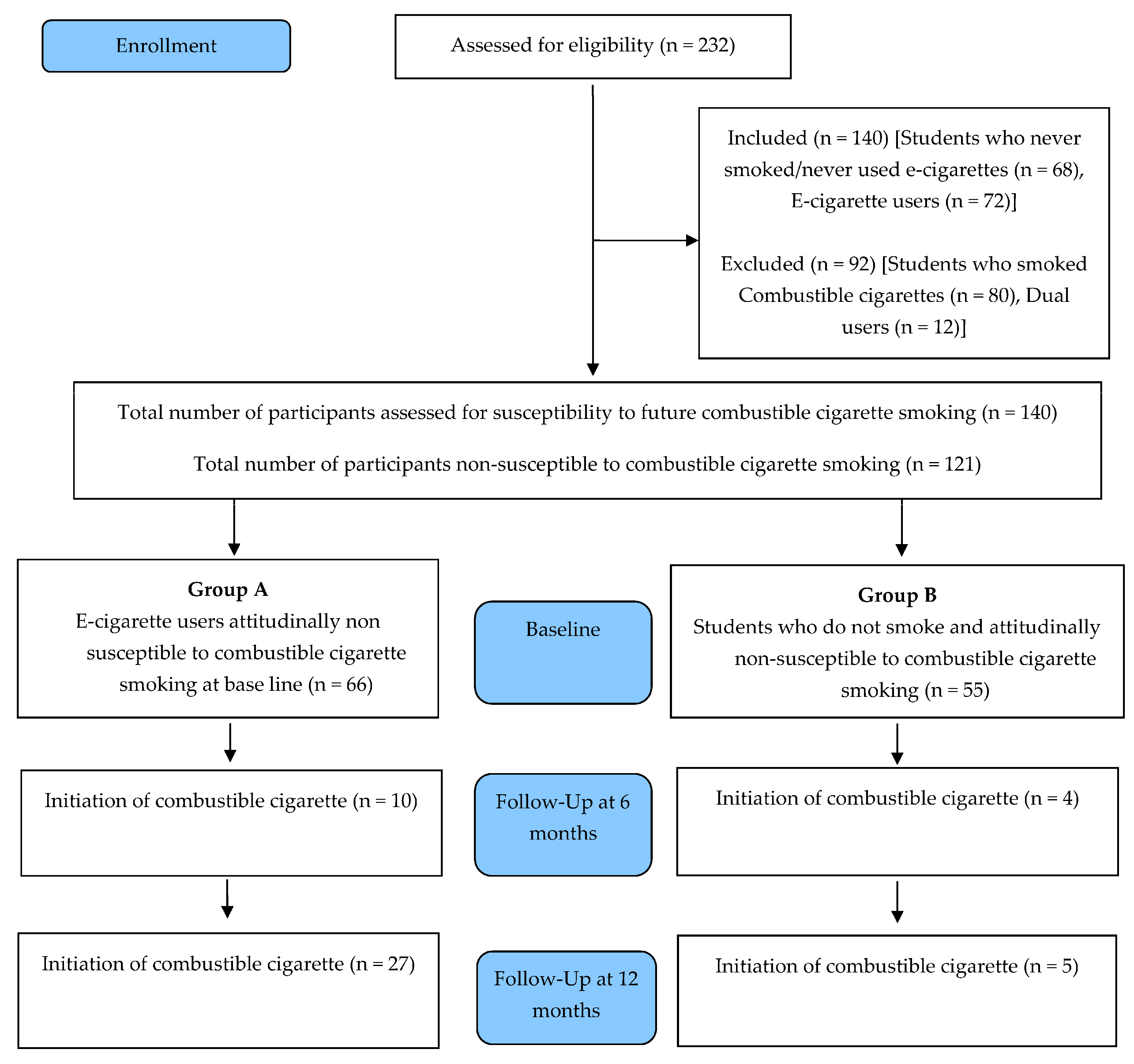

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design

2.2. Sample Size Estimation

2.3. Sampling Technique

2.4. Eligibility Criteria

2.4.1. Inclusion Criteria

2.4.2. Exclusion Criteria

2.5. Data Collection

2.6. Data Collection Tool

“If one of your friends offered you a cigarette, would you try it?” and

“Do you think you will smoke a cigarette sometime in the next year?”

2.7. Study Procedure

2.8. Data Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

Implications of the Study

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gilbert, H.A. Smokeless Non-Tobacco Cigarette. U.S. Patent No. 3,200,819, 1965. Brown & Williamson Collection. Bates No. 570328916-570328920. Available online: http://industrydocuments.library.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/hzxb0140 (accessed on 28 March 2024).

- Lik, H. Electronic Atomization Cigarette. U.S. Patent 8393331 B2, 2013. Available online: https://docs.google.com/viewer?url=patentimages.storage.googleapis.com/pdfs/US8393331 (accessed on 28 March 2024).

- Regan, A.K.; Promoff, G.; Dube, S.R.; Arrazola, R. Electronic Nicotine Delivery Systems: Adult Use and Awareness of the “E-Cigarette” in the USA. Tob. Control 2011, 22, 19–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanford, Z.; Goebel, L.J. E-Cigarettes: An up to Date Review and Discussion of the Controversy. West Va. Med. J. 2014, 110, 10–15. [Google Scholar]

- King, B.A.; Alam, S.; Promoff, G.; Arrazola, R.; Dube, S.R. Awareness and Ever-Use of Electronic Cigarettes among U.S. Adults, 2010–2011. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2013, 15, 1623–1627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Kornfield, R.; Szczypka, G.; Emery, S.L. A Cross-Sectional Examination of Marketing of Electronic Cigarettes on Twitter. Tob. Control 2014, 23, iii26–iii30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CDC Electronic Cigarettes. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/basic_information/e-cigarettes/index.htm (accessed on 28 March 2024).

- Olmedo, P.; Goessler, W.; Tanda, S.; Grau-Perez, M.; Jarmul, S.; Aherrera, A.; Chen, R.; Hilpert, M.; Cohen, J.E.; Navas-Acien, A.; et al. Metal Concentrations in E-Cigarette Liquid and Aerosol Samples: The Contribution of Metallic Coils. Environ. Health Perspect. 2018, 126, 027010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sleiman, M.; Logue, J.M.; Montesinos, V.N.; Russell, M.L.; Litter, M.I.; Gundel, L.A.; Destaillats, H. Emissions from Electronic Cigarettes: Key Parameters Affecting the Release of Harmful Chemicals. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016, 50, 9644–9651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (US) Office on Smoking and Health. Preventing Tobacco Use among Youth and Young Adults. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK99237/ (accessed on 28 May 2023).

- Lee, H.-W.; Park, S.-H.; Weng, M.; Wang, H.-T.; Huang, W.C.; Lepor, H.; Wu, X.-R.; Chen, L.-C.; Tang, M. E-Cigarette Smoke Damages DNA and Reduces Repair Activity in Mouse Lung, Heart, and Bladder as Well as in Human Lung and Bladder Cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, E1560–E1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madison, M.C.; Landers, C.T.; Gu, B.-H.; Chang, C.-Y.; Tung, H.-Y.; You, R.; Hong, M.J.; Baghaei, N.; Song, L.-Z.; Porter, P.; et al. Electronic Cigarettes Disrupt Lung Lipid Homeostasis and Innate Immunity Independent of Nicotine. J. Clin. Investig. 2019, 129, 4290–4304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergman, B.C.; Perreault, L.; Hunerdosse, D.; Kerege, A.; Playdon, M.; Samek, A.M.; Eckel, R.H. Novel and Reversible Mechanisms of Smoking-Induced Insulin Resistance in Humans. Diabetes 2012, 61, 3156–3166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidel, R. Reducing the Health Consequences of Smoking: 25 Years of Progress. A Report of the Surgeon General. Popul. Dev. Rev. 1989, 15, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batra, V.; Patkar, A.A.; Berrettini, W.H.; Weinstein, S.P.; Leone, F.T. The Genetic Determinants of Smoking. Chest 2003, 123, 1730–1739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sundar, I.K.; Javed, F.; Romanos, G.E.; Rahman, I. E-Cigarettes and Flavorings Induce Inflammatory and Pro-Senescence Responses in Oral Epithelial Cells and Periodontal Fibroblasts. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 77196–77204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tellez, C.S.; Juri, D.E.; Phillips, L.M.; Do, K.; Yingling, C.M.; Thomas, C.P.; Dye, W.W.; Wu, G.; Kishida, S.; Kiyono, T.; et al. Cytotoxicity and Genotoxicity of E-Cigarette Generated Aerosols Containing Diverse Flavoring Products and Nicotine in Oral Epithelial Cell Lines. Toxicol. Sci. 2021, 179, 220–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ralho, A.; Coelho, A.; Ribeiro, M.; Paula, A.; Amaro, I.; Sousa, J.; Marto, C.; Ferreira, M.; Carrilho, E. Effects of Electronic Cigarettes on Oral Cavity: A Systematic Review. J. Evid. Based Dent. Pract. 2019, 19, 101318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knorst, M.M.; Benedetto, I.G.; Hoffmeister, M.C.; Gazzana, M.B. The Electronic Cigarette: The New Cigarette of the 21st Century? J. Bras. Pneumol. 2014, 40, 564–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hammond, D.; Reid, J.L.; Cole, A.G.; Leatherdale, S.T. Electronic Cigarette Use and Smoking Initiation among Youth: A Longitudinal Cohort Study. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 2017, 189, E1328–E1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jankowski, M.; Krzystanek, M.; Zejda, J.E.; Majek, P.; Lubanski, J.; Lawson, J.A.; Brozek, G. E-Cigarettes Are More Addictive than Traditional Cigarettes—A Study in Highly Educated Young People. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhave, S.Y.; Chadi, N. E-Cigarettes and Vaping: A Global Risk for Adolescents. Indian Pediatr. 2021, 58, 315–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ban on the Advertising of Electronic Cigarettes and Accessories. New South Wales. 2015. Available online: https://www.health.nsw.gov.au (accessed on 28 May 2023).

- 47 Countries Have Banned E-Cigarettes. Available online: https://profglantz.com/2021/11/03/47-countries-have-banned-e-cigarettes/ (accessed on 28 May 2023).

- Aqeeli, A.A.; Makeen, A.M.; Al Bahhawi, T.; Ryani, M.A.; Bahri, A.A.; Alqassim, A.Y.; El-Setouhy, M. Awareness, Knowledge and Perception of Electronic Cigarettes among Undergraduate Students in Jazan Region, Saudi Arabia. Health Soc. Care Community 2020, 30, 706–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saudi FDA Issues. New Regulations for Tobacco Imported for Personal Use 200 Cigarettes or 500 Grams for All Other Types of Tobacco Customs Directs Ports to Abide by SFDA Regulations. Available online: https://www.sfda.gov.sa/ (accessed on 28 May 2023).

- Althobaiti, N.K.; Mahfouz, M.E.M. Prevalence of Electronic Cigarette Use in Saudi Arabia. Cureus 2022, 14, e25731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, S.; Fageeh, H.; Mushtaq, S.; Ajmal, M.; Chalikkandy, S.; Ashi, H.; Ahmad, Z.; Khan, S.; Khanagar, S.; Varadarajan, S.; et al. Prevalence of Electronic Cigarette Usage among Medical Students in Saudi Arabia—A Systematic Review. Niger. J. Clin. Pract. 2022, 25, 765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharanesha, R.; Alkhaldi, A.; Alshehri, A.; Alanazi, M.; Al-shammri, T.; Alanazi, F. Knowledge and Perception of E-Cigarettes among Dental Students in Riyadh Region Saudi Arabia. J. Pharm. Bioallied Sci. 2022, 14, 340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhajj, M.N.; Al-Maweri, S.A.; Folayan, M.O.; Halboub, E.; Khader, Y.; Omar, R.; Amran, A.G.; Al-Batayneh, O.B.; Celebić, A.; Persic, S.; et al. Knowledge, Beliefs, Attitude, and Practices of E-Cigarette Use among Dental Students: A Multinational Survey. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0276191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aluckal, E.; Kunnilathu, A. Role of Dental Professionals in Tobacco Control. Available online: https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/288292418.pdf (accessed on 28 May 2023).

- Gordon, J.S.; Albert, D.A.; Crews, K.M.; Fried, J. Tobacco Education in Dentistry and Dental Hygiene. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2009, 28, 517–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trybek, G.; Preuss, O.; Aniko-Wlodarczyk, M.; Kuligowski, P.; Gabrysz-Trybek, E.; Suchanecka, A.; Grzywacz, A.; Niewczas, P. The Effect of Nicotine on Oral Health. Balt. J. Health Phys. Act. 2018, 10, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, J.S.; Severson, H.H. Tobacco Cessation through Dental Office Settings. J. Dent. Educ. 2001, 65, 354–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanioka, T.; Ojima, M.; Tanaka, H.; Naito, M.; Hamajima, N.; Matsuse, R. Intensive Smoking-Cessation Intervention in the Dental Setting. J. Dent. Res. 2009, 89, 66–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leventhal, A.M.; Strong, D.R.; Kirkpatrick, M.G.; Unger, J.B.; Sussman, S.; Riggs, N.R.; Stone, M.D.; Khoddam, R.; Samet, J.M.; Audrain-McGovern, J. Association of Electronic Cigarette Use with Initiation of Combustible Tobacco Product Smoking in Early Adolescence. JAMA 2015, 314, 700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wills, T.A.; Knight, R.; Sargent, J.D.; Gibbons, F.X.; Pagano, I.; Williams, R.J. Longitudinal Study of E-Cigarette Use and Onset of Cigarette Smoking among High School Students in Hawaii. Tob. Control 2016, 26, 34–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Primack, B.A.; Soneji, S.; Stoolmiller, M.; Fine, M.J.; Sargent, J.D. Progression to Traditional Cigarette Smoking after Electronic Cigarette Use among US Adolescents and Young Adults. JAMA Pediatr. 2015, 169, 1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrington-Trimis, J.L.; Berhane, K.; Unger, J.B.; Cruz, T.B.; Urman, R.; Chou, C.P.; Howland, S.; Wang, K.; Pentz, M.A.; Gilreath, T.D.; et al. The E-Cigarette Social Environment, E-Cigarette Use, and Susceptibility to Cigarette Smoking. J. Adolesc. Health 2016, 59, 75–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaffee, B.W.; Watkins, S.L.; Glantz, S.A. Electronic Cigarette Use and Progression from Experimentation to Established Smoking. Pediatrics 2018, 141, e20173594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watkins, S.L.; Glantz, S.A.; Chaffee, B.W. Association of Noncigarette Tobacco Product Use with Future Cigarette Smoking among Youth in the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health (PATH) Study, 2013–2015. JAMA Pediatr. 2018, 172, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conner, M.; Grogan, S.; Simms-Ellis, R.; Flett, K.; Sykes-Muskett, B.; Cowap, L.; Lawton, R.; Armitage, C.J.; Meads, D.; Torgerson, C.; et al. Do Electronic Cigarettes Increase Cigarette Smoking in UK Adolescents? Evidence from a 12-Month Prospective Study. Tob. Control 2017, 27, 365–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miech, R.; Patrick, M.E.; O’Malley, P.M.; Johnston, L.D. E-Cigarette Use as a Predictor of Cigarette Smoking: Results from a 1-Year Follow-up of a National Sample of 12th Grade Students. Tob. Control 2017, 26, e106–e111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrington-Trimis, J.L.; Kong, G.; Leventhal, A.M.; Liu, F.; Mayer, M.; Cruz, T.B.; Krishnan-Sarin, S.; McConnell, R. E-Cigarette Use and Subsequent Smoking Frequency among Adolescents. Pediatrics 2018, 142, e20180486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kinnunen, J.M.; Ollila, H.; Minkkinen, J.; Lindfors, P.L.; Timberlake, D.S.; Rimpelä, A.H. Nicotine Matters in Predicting Subsequent Smoking after E-Cigarette Experimentation: A Longitudinal Study among Finnish Adolescents. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2019, 201, 182–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, K.M.; Fetterman, J.L.; Benjamin, E.J.; Bhatnagar, A.; Barrington-Trimis, J.L.; Leventhal, A.M.; Stokes, A. Association of Electronic Cigarette Use with Subsequent Initiation of Tobacco Cigarettes in US Youths. JAMA Netw. Open 2019, 2, e187794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, A.S.; Xu, S. Associations of Flavored E-Cigarette Uptake with Subsequent Smoking Initiation and Cessation. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e203826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owotomo, O.; Stritzel, H.; McCabe, S.E.; Boyd, C.J.; Maslowsky, J. Smoking Intention and Progression from E-Cigarette Use to Cigarette Smoking. Pediatrics 2020, 146, e2020002881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odani, S.; Armour, B.S.; King, B.A.; Agaku, I.T. E-Cigarette Use and Subsequent Cigarette Initiation and Sustained Use among Youth, U.S., 2015–2017. J. Adolesc. Health 2019, 66, 34–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahai, H.; Khurshid, A. Formulae and Tables for the Determination of Sample Size and Power in Clinical Trials for Testing Differences in Proportions for the Two Sample Design: A Review. Stat. Med. 1996, 15, 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, W.S.; Gilpin, E.A.; Farkas, A.J.; Pierce, J.P. Determining the Probability of Future Smoking among Adolescents. Addiction 2001, 96, 313–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakefield, M.; Kloska, D.D.; O’Malley, P.M.; Johnston, L.D.; Chaloupka, F.; Pierce, J.; Giovino, G.; Ruel, E.; Flay, B.R. The Role of Smoking Intentions in Predicting Future Smoking among Youth: Findings from Monitoring the Future Data. Addiction 2004, 99, 914–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunnell, R.E.; Agaku, I.T.; Arrazola, R.A.; Apelberg, B.J.; Caraballo, R.S.; Corey, C.G.; Coleman, B.N.; Dube, S.R.; King, B.A. Intentions to Smoke Cigarettes among Never-Smoking US Middle and High School Electronic Cigarette Users: National Youth Tobacco Survey, 2011–2013. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2014, 17, 228–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grana, R.; Benowitz, N.; Glantz, S.A. E-Cigarettes. Circulation 2014, 129, 1972–1986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pepper, J.K.; Brewer, N.T. Electronic Nicotine Delivery System (Electronic Cigarette) Awareness, Use, Reactions and Beliefs: A Systematic Review. Tob. Control 2013, 23, 375–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carroll Chapman, S.L.; Wu, L.-T. E-Cigarette Prevalence and Correlates of Use among Adolescents versus Adults: A Review and Comparison. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2014, 54, 43–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinnunen, J.M.; Ollila, H.; El-Amin, S.E.-T.; Pere, L.A.; Lindfors, P.L.; Rimpelä, A.H. Awareness and Determinants of Electronic Cigarette Use among Finnish Adolescents in 2013: A Population-Based Study. Tob. Control 2014, 24, e264–e270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cullen, K.A.; Ambrose, B.K.; Gentzke, A.S.; Apelberg, B.J.; Jamal, A.; King, B.A. Notes from the Field: Use of Electronic Cigarettes and Any Tobacco Product among Middle and High School Students—United States, 2011–2018. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2018, 67, 1276–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saudi Arabia—Tobacco Control Laws. Available online: https://www.tobaccocontrollaws.org/legislation/saudi-arabia (accessed on 29 May 2023).

- Smoking in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia: Findings from the Saudi Health Interview Survey; Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation K.S.A. Available online: https://www.healthdata.org (accessed on 28 March 2024).

- Carr, A.B.; Ebbert, J. Interventions for Tobacco Cessation in the Dental Setting. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2012, 2012, CD005084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warnakulasuriya, S. Effectiveness of Tobacco Counseling in the Dental Office. J. Dent. Educ. 2002, 66, 1079–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomar, S.L. Dentistry’s Role in Tobacco Control. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 2001, 132 (Suppl. 1), 30S–35S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomar, S.L.; Winn, D.M.; Swango, P.A.; Giovino, G.A.; Kleinman, D.V. Oral Mucosal Smokeless Tobacco Lesions among Adolescents in the United States. J. Dent. Res. 1997, 76, 1277–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hashim, R.; Thomson, W.M.; Pack, A.R.C. Smoking in Adolescence as a Predictor of Early Loss of Periodontal Attachment. Community Dent. Oral Epidemiol. 2001, 29, 130–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petersen, P.E. Oral Cancer Prevention and Control—The Approach of the World Health Organization. Oral Oncol. 2009, 45, 454–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ke, O.; Ballard, J.A. Attitudes of Patients toward Smoking by Health Professionals. Public Health Rep. 1992, 107, 335–339. [Google Scholar]

- Pipe, A.; Sorensen, M.; Reid, R. Physician Smoking Status, Attitudes toward Smoking, and Cessation Advice to Patients: An International Survey. Patient Educ. Couns. 2009, 74, 118–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AlSwuailem, A.S.; AlShehri, M.K.; Al-Sadhan, S. Smoking among Dental Students at King Saud University: Consumption Patterns and Risk Factors. Saudi Dent. J. 2014, 26, 88–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahamad Sobri, M.; Azlan, A.; Bohari, N.M.; Mohd Radzi, N.; Bakri, N. Knowledge, Attitude, and Perceived Harm of E-Cigarette Use Behaviour among Medical and Dental Undergraduate Students in UiTM. Compend. Oral Sci. 2022, 9, 69–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsanea, S.; Alrabiah, Z.; Samreen, S.; Syed, W.; Bin Khunayn, R.M.; Al-Arifi, N.M.; Alenazi, M.; Alghadeer, S.; Alhossan, A.; Alwhaibi, A.; et al. Prevalence, Knowledge and Attitude toward Electronic Cigarette Use among Male Health Colleges Students in Saudi Arabia—A Cross-Sectional Study. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 827089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurdi, R.; Al-Jayyousi, G.F.; Yaseen, M.; Ali, A.; Mosleh, N.; Abdul Rahim, H.F. Prevalence, Risk Factors, Harm Perception, and Attitudes toward E-Cigarette Use among University Students in Qatar: A Cross-Sectional Study. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 682355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wamamili, B.; Wallace-Bell, M.; Richardson, A.; Grace, R.C.; Coope, P. Electronic Cigarette Use among University Students Aged 18–24 Years in New Zealand: Results of a 2018 National Cross-Sectional Survey. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e035093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nodora, J.; Hartman, S.J.; Strong, D.R.; Messer, K.; Vera, L.E.; White, M.M.; Portnoy, D.B.; Choiniere, C.J.; Vullo, G.C.; Pierce, J.P. Curiosity Predicts Smoking Experimentation Independent of Susceptibility in a US National Sample. Addict. Behav. 2014, 39, 1695–1700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Staff, J.; Kelly, B.C.; Maggs, J.L.; Vuolo, M. Adolescent Electronic Cigarette Use and Tobacco Smoking in the Millennium Cohort Study. Addiction 2021, 117, 484–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, S.; Coffman, D.L.; Liu, B.; Xu, Y.; He, J.; Niaura, R.S. Relationships between E-Cigarette Use and Subsequent Cigarette Initiation among Adolescents in the PATH Study: An Entropy Balancing Propensity Score Analysis. Prev. Sci. 2021, 23, 608–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahab, L.; Beard, E.; Brown, J. Association of Initial E-Cigarette and Other Tobacco Product Use with Subsequent Cigarette Smoking in Adolescents: A Cross-Sectional, Matched Control Study. Tob. Control 2020, 30, tobaccocontrol-2019-055283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alves, J.; Perelman, J.; Soto-Rojas, V.; Richter, M.; Rimpelä, A.; Loureiro, I.; Federico, B.; Kuipers, M.A.G.; Kunst, A.E.; Lorant, V. The Role of Parental Smoking on Adolescent Smoking and Its Social Patterning: A Cross-Sectional Survey in Six European Cities. J. Public Health 2016, 39, fdw040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leonardi-Bee, J.; Jere, M.L.; Britton, J. Exposure to Parental and Sibling Smoking and the Risk of Smoking Uptake in Childhood and Adolescence: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Thorax 2011, 66, 847–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Žaloudíková, I.; Hrubá, D.; Samara, I. Parental Education and Family Status—Association with Children’s Cigarette Smoking. Cent. Eur. J. Public Health 2012, 20, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inagaki, K.; Hayashi, J.I.; Ting, C.-Y.; Noguchi, T.; Senda, A.; Hanamura, H.; Morita, I.; Nakagaki, H.; Koide, T.; Shieh, T.-Y.; et al. Dental Undergraduates’ Smoking Status and Social Nicotine Dependence in Japan and Taiwan—Comparison between Two Dental Schools. Jpn. J. Tob. Control 2008, 3, 81–85. [Google Scholar]

- Almutairi, K.M. Smoking among Saudi Students: A Review of Risk Factors and Early Intentions of Smoking. J. Community Health 2014, 39, 901–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maharani, D.A.; Nadira, K.V.; Setiawati, F.; El Tantawi, M. Intention to Provide Tobacco Cessation Counseling among Indonesian Dental Students and Association with the Theory of Planned Behavior. BMC Oral Health 2021, 21, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Priya, H.; Deb Barma, M.; Purohit, B.M.; Agarwal, D.; Bhadauria, U.S.; Tewari, N.; Gupta, S.; Mishra, D.; Morankar, R.; Mathur, V.P.; et al. Global Status of Knowledge, Attitude and Practice on Tobacco Cessation Interventions among Dental Professionals: A Systematic Review. Tob. Use Insights 2022, 15, 1179173X2211372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koka, K.; Yadlapalli, S.; Pillarisetti, P.; Yasangi, M.; Yaragani, A.; Kummamuru, S. The Barriers for Tobacco Cessation Counseling in Teaching Health Care Institutions: A Qualitative Data Analysis Using MAXQDA Software. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 2021, 10, 3262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alhussain, A.A.; AlSaif, R.F.; Alahmari, J.M.; Aleheideb, A.A. Perceptions of Smoking Cessation Counseling among Dental Students in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia: A Cross-Sectional Study. Imam J. Appl. Sci. 2019, 4, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, J.M.; Arnett, M.R.; Loewen, J.; Romito, L.; Gordon, S.C. Tobacco Dependence Education. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 2016, 147, 405–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, J.M.; Ramseier, C.A.; Mattheos, N.; Schoonheim-Klein, M.; Compton, S.; Al-Hazmi, N.; Polychronopoulou, A.; Suvan, J.; Antohé, M.E.; Forna, D.A.; et al. Education of Tobacco Use Prevention and Cessation for Dental Professionals—A Paradigm Shift. Int. Dent. J. 2010, 60, 60–72. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Vanobbergen, J.; Nuytens, P.; van Herk, M.; De Visschere, L. Dental Students? Attitude towards Anti-Smoking Programmes: A Study in Flanders, Belgium. Eur. J. Dent. Educ. 2007, 11, 177–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghasemi, H.; Khami, M.R.; Virtanen, J.I.; Vehkalahti, M.M. Does Smoking Hamper Oral Self-Care among Dental Professionals? J. Dent. 2015, 12, 333–339. [Google Scholar]

- Ramseier, C.A.; Christen, A.; McGowan, J.; McCartan, B.; Minenna, L.; Ohrn, K.; Walter, C. Tobacco Use Prevention and Cessation in Dental and Dental Hygiene Undergraduate Education. Oral Health Prev. Dent. 2006, 4, 49–60. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

| Study Parameters | Frequency | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Current use of tobacco | Yes | 164 | 70.7% |

| No | 68 | 29.3% | |

| Total | 232 | 100% | |

| Type of cigarette usage | Combustible cigarette | 80 | 48.8% |

| Electronic cigarette | 72 | 43.9% | |

| Both | 12 | 7.3% | |

| Total | 164 | 100% | |

| Statements | Responses | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| If one of your friends offered you a cigarette, would you try it? | Definitely Yes | 0 | 0% |

| Probably Yes | 0 | 0% | |

| Definitely No | 121 | 86.43% | |

| Probably No | 19 | 13.57% | |

| Do you think you will smoke combustible cigarette in the next year? | Definitely Yes | 0 | 0% |

| Probably Yes | 0 | 0% | |

| Definitely No | 140 | 100% | |

| Probably No | 0 | 0% |

| Study Parameters | Frequency | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age group wise distribution | 21 | 13 | 10.7% |

| 22 | 31 | 25.6% | |

| 23 | 45 | 37.2% | |

| 24 | 31 | 25.6% | |

| 25 | 1 | 0.8% | |

| Mean Age | 22.80 ± 0.98 | ||

| Biological sex | Male | 4 | 3.3% |

| Female | 117 | 96.7% | |

| Father’s education | Illiterate | 16 | 13.2% |

| Intermediate School | 17 | 14.0% | |

| High School | 30 | 25.0% | |

| Bachelor’s/Master’s Degrees/Above | 58 | 47.8% | |

| Mother’s education | Illiterate | 09 | 7.5% |

| Intermediate School | 07 | 5.8% | |

| High School | 53 | 43.8% | |

| Bachelor’s/Master’s Degrees/Above | 52 | 42.9% | |

| Family income | Less than SAR 10,000 | 46 | 38.0% |

| SAR 10,000–19,000 | 36 | 29.7% | |

| SAR 20,000 and Above | 39 | 32.3% | |

| Parental cigarette smoking | Yes | 59 | 48.8% |

| No | 62 | 51.2% | |

| Smoking among friends | Yes | 77 | 63.6% |

| No | 44 | 36.4% | |

| Total | 121 | 100% | |

| Study Parameters | At Baseline | At 6 Months | At 12 Months | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency | Percentage | Frequency | Percentage | Frequency | Percentage | |

| Usage of combustible cigarettes among e-cigarette users | Nil | Nil | 10 | 15.1% | 27 | 40.9% |

| Usage of combustible cigarettes among never-users | Nil | Nil | 4 | 7.2% | 5 | 9.09% |

| Independent Variable | Dependent Variable | Chi-Square Test | df | Sign |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mother’s Education | Do you smoke? | 0.96 | 3 | 0.81 |

| Father’s Education | 34.68 | 3 | 0.00 * | |

| Parental Cigarette Smoking | 13.44 | 1 | 0.00 * | |

| Parental Cigarette Smoking | What do you smoke? | 13.44 | 1 | 0.00 * |

| Cigarette Smoking among Friends | 16.94 | 1 | 0.00 * | |

| Family Income | 37.74 | 2 | 0.00 * | |

| Electronic Cigarette is Healthier than Regular Combustible Cigarettes | 74.61 | 1 | 0.00 * |

| Variable | df | Sign | Exp (B) | 95% Confidence Interval of RR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||

| E-cigarette ref: non-user | 1 | 0.000 | 9.395 | 3.039 | 29.045 |

| Family income (SAR 20,000 and above) Family Income (SAR 10,000–19,000) Ref: SAR < 10,000 | 1 | 0.012 | 0.286 | 0.108 | 0.758 |

| 1 | 0.001 | 0.026 | 0.003 | 0.208 | |

| Father education: Bachelor’s/Master’s degrees | 1 | 0.005 | 0.180 | 0.054 | 0.604 |

| Father education: high school | 1 | 0.487 | 0.651 | 0.195 | 2.179 |

| Father education: intermediate school ref: illiterate | 1 | 0.356 | 0.511 | 0.123 | 2.122 |

| Parental cigarette smoking ref: non-users | 1 | 0.012 | 2.667 | 1.241 | 5.730 |

| Omnibus Test of Model Coeiffcient | p = 0.000 | Nagelkerke R Square | 0.307 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Khanagar, S.B.; Aldawas, I.; Alrusaini, S.K.; Albalawi, F.; Alshehri, A.; Awawdeh, M.; Iyer, K.; Divakar, D.D. Association of Electronic Cigarette Usage with the Subsequent Initiation of Combustible Cigarette Smoking among Dental Students in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia: A Longitudinal Study. Healthcare 2024, 12, 1092. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12111092

Khanagar SB, Aldawas I, Alrusaini SK, Albalawi F, Alshehri A, Awawdeh M, Iyer K, Divakar DD. Association of Electronic Cigarette Usage with the Subsequent Initiation of Combustible Cigarette Smoking among Dental Students in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia: A Longitudinal Study. Healthcare. 2024; 12(11):1092. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12111092

Chicago/Turabian StyleKhanagar, Sanjeev B., Ibrahim Aldawas, Salman Khalid Alrusaini, Farraj Albalawi, Aram Alshehri, Mohammed Awawdeh, Kiran Iyer, and Darshan Devang Divakar. 2024. "Association of Electronic Cigarette Usage with the Subsequent Initiation of Combustible Cigarette Smoking among Dental Students in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia: A Longitudinal Study" Healthcare 12, no. 11: 1092. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12111092

APA StyleKhanagar, S. B., Aldawas, I., Alrusaini, S. K., Albalawi, F., Alshehri, A., Awawdeh, M., Iyer, K., & Divakar, D. D. (2024). Association of Electronic Cigarette Usage with the Subsequent Initiation of Combustible Cigarette Smoking among Dental Students in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia: A Longitudinal Study. Healthcare, 12(11), 1092. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12111092

_MD__MPH_PhD.png)