Abstract

Background: Data on the health-related quality of life (HRQoL) for invasive meningococcal disease (IMD) survivors, particularly among adolescents and young adults (AYAs), are limited. This study aimed to investigate the in-depth experiences and impacts of IMD on AYAs. Methods: Participants were recruited from two Australian states, Victoria and South Australia. We conducted qualitative, semi-structured interviews with 30 patients diagnosed with IMD between 2016 and 2021. The interview transcripts were analyzed thematically. Results: Of the participants, 53% were aged 15–19 years old, and 47% were aged 20–24. The majority (70%) were female. Seven themes relating to the participants’ experience of IMD were identified: (1) underestimation of the initial symptoms and then rapid escalation of symptoms; (2) reliance on social support for emergency care access; (3) the symptoms prompting seeking medical care varied, with some key symptoms missed; (4) challenges in early medical diagnosis; (5) traumatic and life-changing experience; (6) a lingering impact on HRQoL; and (7) gaps in the continuity of care post-discharge. Conclusion: The themes raised by AYA IMD survivors identify multiple areas that can be addressed during their acute illness and recovery. Increasing awareness of meningococcal symptoms for AYAs may help reduce the time between the first symptoms and the first antibiotic dose, although this remains a challenging area for improvement. After the acute illness, conducting HRQoL assessments and providing multidisciplinary support will assist those who require more intensive and ongoing assistance during their recovery.

1. Introduction

Invasive meningococcal disease (IMD) is one of the most common causes of death due to an infectious disease in developed countries, such as Australia [1]. IMD manifests as septicemia and/or meningitis [2], and survivors can often experience permanent sequelae beyond their acute infection [3,4]. Disease sequelae can be present in both the short- and long-term recovery periods, affecting survivors’ health-related quality of life (HRQoL) [5,6].

While IMD affects all age groups, its incidence in most countries, including Australia, has a bimodal distribution, peaking in children (0–4 years) and then having a smaller peak in adolescents and young adults (AYAs) (15–25 years) [7,8,9]. IMD in AYAs is an important consideration because this is a time of increased independence, as well as the completion of secondary and tertiary education and training for entering the workforce. Additionally, this is a period of significant neurological development, with the maturation of the brain structure and neurochemical pathways [10]. The pathology of IMD can interrupt this development, causing ongoing neurological issues. Previous research has shown that AYA survivors of IMD have a lower academic performance and higher rates of mental ill health compared with controls [5,11].

Early diagnosis of meningococcal disease is difficult because the initial symptoms, such as fever, headache, muscle aches, and vomiting, are similar to common viral infections [12]. The triad of the classical features of meningitis, namely fever, neck stiffness, and altered mental state, is not always all present, resulting in health professionals missing bacterial meningitis cases [13]. Even when they are all present, appropriate and timely antibiotic therapy can be delayed [14]. Another classical sign of meningococcal disease is a hemorrhagic, non-blanching rash. However, this rash often appears later in the acute illness and not in all presentations [15]. In a UK study of adolescents aged 15–16 years with IMD, approximately 66% developed a rash, on average about 19 h after developing their first symptoms [16]. The progression of the disease is usually rapid, resulting in hospitalization and often intensive care admission. Among adolescents aged 16 years, the case fatality rate is estimated at 10.4%, increasing to 15.0% in young adults aged 28 years [17]. Reducing the time from healthcare presentation to antibiotic therapy reduces mortality for bacterial meningitis and sepsis [18,19].

IMD is a largely vaccine-preventable disease, with multi-component vaccines available for the A, C, W, and Y strains (MenACWY) and the B strain (MenB). However, few countries have publicly funded meningococcal B vaccine programs for adolescents due to unknown or unfavorable cost-effectiveness analyses, hindered by a lack of contemporary data on the disease burden [20]. One study [21] has explored the psychosocial impacts experienced by young people with IMD, but there remains a lack of published qualitative data.

HRQoL is a multidimensional concept that can be described as an individual’s personal health status [22]. Despite lacking a universal definition, most descriptions suggest that HRQoL is an individual’s subjective view of their own health status and includes the dimensions of physical, emotional, and social functioning [22]. Despite being a subjective concept, HRQoL can be measured quantitatively using generic HRQoL instruments. Another option is to develop or adapt instruments psychometrically tested to be specific to the disease of interest [23]. Tools developed for or adapted specifically to conditions such as IMD have the potential to provide unique information that is not captured by more generic instruments. However, a Delphi process that included clinicians and patient representatives revealed a preference for a generic HRQoL tool over an adapted or newly developed tool for assessing the HRQoL of survivors of IMD [23]. Currently, there is no disease-specific instrument for IMD. In the absence of a disease-specific instrument, HRQoL within specific populations can be assessed with either generic HRQoL instruments (e.g., the short-form 36 [24]) or through qualitative methods.

This qualitative study aims to explore the HRQoL and lived experience of adolescents following IMD, spanning from their initial symptoms to long-term recovery.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

We conducted semi-structured qualitative interviews with 17–25-year-olds diagnosed with IMD and enrolled in the Long-term Impact of Invasive Meningococcal Disease in Australian Adolescents and Young Adults (AMEND) study (NCT03798574) [25]. Interviews were conducted with IMD survivors in South Australia and Victoria by the research nurses M.M. and M.A. and the research scientist L.S. The participants were unknown to the interviewers prior to their study appointments. The study’s aims were described to the participants prior to them giving consent on written participant information sheets and in verbal conversation.

2.2. Recruitment

This research was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of the Women’s and Children’s Health Network (HREC/14/WCHN/024) and Monash Health (16093A). Eligible participants were prospectively and retrospectively identified through hospital records and by admitting physicians. All eligible retrospective participants were sent a letter inviting them to participate in the study. To be eligible, participants were required to meet the following criteria: confirmed IMD diagnosis by culture or polymerase chain reaction of Neisseria meningitidis in the blood or cerebrospinal fluid and being aged between 15 and 25 years at the time of IMD hospitalization. Potential participants were excluded if they were not fluent in English or had a known pre-existing intellectual disability or intracranial pathology.

Eligible participants were sent a letter inviting them to participate in the AMEND study or were recruited prior to discharge from the hospital. Consent was obtained prior to the interview. The participants received reimbursement for the time they spent completing the study process, including the semi-structured interviews. Assessments were performed between 2 and 10 years post-IMD diagnosis.

2.3. Data Collection

Face-to-face interviews were conducted individually at Women’s and Children’s Hospital in Adelaide and Monash Health in Melbourne. Each interview was audiotaped and transcribed with only the participant and the interviewer present. Transcripts were not returned to the participants for comments or corrections. The interviews, facilitated by an interview schedule (see Supplementary Material: AMEND Semi-Structured Interview Schedule) with open-ended questions, encouraged participant-directed responses. The questionnaire was developed by the study investigators and reviewed by an external qualitative research expert. Following the initial round of interviews, minor adjustments were made to refine the questions. The duration of the interviews ranged from 10 to 40 min. The participants were asked to describe how their experience with IMD had affected their HRQoL from the time they were hospitalized to the date of the interview. When needed, probing questions regarding the physical, emotional, and social aspects of HRQoL were used to elicit responses from participants. Data were collected until saturation was reached [26]. A case note review was conducted for the baseline characteristics. The Index of Relative Socioeconomic Disadvantage (IRSD) was used to classify the participants’ socioeconomic statuses based on postcode [27], and the Charlson Comorbidity Index was used for pre-existing comorbidities [28]. Participants were assigned a diagnosis of septicemia, meningitis, or mixed meningitis and septicemia by a pediatrician external to the study.

2.4. Analysis

The transcripts were thematically analyzed [29] using NVivo 12 software (QSR International, Chadstone, Victoria, Australia) following a critical realist paradigm. Critical realism recognizes that the world functions within a complex, multidimensional system, and therefore the phenomena that patients experience are likely to be informed by their generation of meaning and the broader structures within which patients exist [30]. The analysis was led by one author (J.M.), with each step audited by another (M.M.) to ensure consistency in the analysis. The transcripts were read several times to gain familiarity with individual accounts, with preliminary notes on salient topics. The coding followed an inductive approach, wherein the codes were driven by the data rather than a predetermined framework. Thus, the coding of earlier transcripts informed subsequent transcripts, and earlier transcripts were revisited when new themes were identified, ensuring coding consistency. Once each transcript had been analyzed, the codes were merged to form themes. Regular conversations within the research team ensured that the identified themes were captured and supported by the participant views and all relevant themes were included in the analysis. The quotes presented were selected as the most concise and comprehensive illustrations of the themes and labelled with participant numbers.

2.5. Role of the Funding Source

Pfizer funded the AMEND study to evaluate the long-term impact of IMD on the general intellectual functioning and quality of life of Australian AYAs, as described in the ClinicalTrials.gov clinical registry [25]. Pfizer reviewed the study protocol, but this funder had no role in the study design, data collection, or analysis and had no involvement in the development of this publication.

3. Results

Thirty young people participated in the interviews (see Table 1 for the participant characteristics). Prior to IMD, the majority of the participants had no pre-existing comorbidities. More than half of the participants (60%) were classified as having meningitis, with 40% having sepsis without meningitis. Over half of the participants were from the least socioeconomically disadvantaged residential areas. All had serogroup B IMD.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics (N = 30).

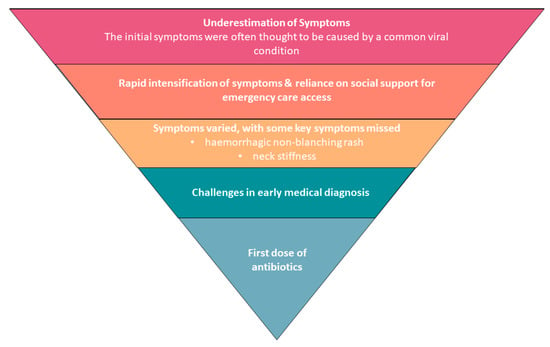

Our thematic analysis identified seven themes from the onset of meningococcal disease to recovery.

- A.

- Potential barriers to timely first dose of antibiotics

- (1)

- Underestimation of initial symptoms and then rapid progression of symptoms

- (2)

- Reliance on social support for emergency care access

- (3)

- Symptoms prompting seeking medical care varied, with some key symptoms missed

- (4)

- Challenges in early medical diagnosis

- B.

- The life-changing impact of meningococcal disease

- (5)

- Traumatic and life-changing experiences of IMD

- C.

- Ongoing HRQoL issues and impacts of IMD

- (6)

- IMD’s lingering impact on health-related quality of life

- (7)

- Gaps in the continuity of care post-discharge for patients and carers

These themes are further described below.

- A.

Figure 1. Barriers to timely first dose of antibiotics.

Figure 1. Barriers to timely first dose of antibiotics. Table 2. Themes and IMD survivor responses identifying potential barriers to a timely first dose of antibiotics.

Table 2. Themes and IMD survivor responses identifying potential barriers to a timely first dose of antibiotics.- B.

- The life-changing impact of meningococcal disease (Table 3)

Table 3. Themes and IMD survivor responses to the impact of meningococcal disease.

Table 3. Themes and IMD survivor responses to the impact of meningococcal disease. - C.

- Ongoing HRQoL issues and impact of IMD (Table 4)

Table 4. Themes and IMD survivor responses—ongoing HRQoL issues and impact of IMD.

Table 4. Themes and IMD survivor responses—ongoing HRQoL issues and impact of IMD.

4. Discussion

This is the first qualitative study to examine HRQoL issues and lived experience in AYAs following IMD. This qualitative research provides an in-depth understanding of AYAs’ experience and the impact of IMD on their HRQoL. The themes from this study identified the life-changing experience of IMD and the lingering impact it had on both the participants in this study and their families and carers, as well as the potential barriers to timely diagnosis and treatment, which represent targets for intervention.

Reducing the time to starting antibiotic therapy reduces mortality for bacterial meningitis [18,31]. The thematic analysis identified that the period from meningococcal symptoms to receiving antibiotics remains an area that could be improved. Most research focuses on the “door-to-needle” time, where the clock starts from hospital presentation to the first appropriate dose of antibiotics [18]. A Croatian study investigating the time from the onset of symptoms to the first appropriate dose of antibiotics found that only 20% of its patients with bacterial meningitis received the appropriate treatment during the first 24 h of the disease onset. They could not investigate the reasons behind these delays [14]. This analysis suggests that some of the reasons behind the delays in healthcare presentations for AYAs include underestimation of the seriousness of their initial symptoms and then rapid deterioration, which often leaves AYAs reliant on help from others to access medical care.

In some cases, the classical signs of meningococcal disease and meningitis were either missed or not considered serious by the participants, including neck stiffness and hemorrhagic rash. The Defeating Meningitis by 2030 global road map, developed by a World Health Organization task force, includes the strategic goal “ensure awareness, among all populations, of the symptoms, signs and consequences of meningitis so that they seek appropriate health care” [32]. One of the key activities in the strategic plan calls for understanding the factors that facilitate or act as barriers to seeking healthcare. This analysis suggests that for AYAs, knowledge of distinct symptoms remains a barrier to seeking healthcare, as does reliance on others, during a time when many are becoming increasingly independent and less reliant on their families. Enhancing public awareness about key meningococcal signs, such as a stiff neck and rashes, may improve the outcomes for AYAs with IMD [33]. Future research should seek to quantitatively assess these dynamics in a larger cohort, exploring the relationship between diagnostic delays, symptom presentation and progression, and patient outcomes.

Delays in effective treatment for more than two hours after presenting to a hospital are associated with more than double the odds of death in patients with community-acquired bacterial meningitis [18]. This qualitative analysis did not investigate the reasons behind the delays in receiving an appropriate antibiotic following initial medical presentation. However, several participants had significant delays in receiving antibiotics. The causes of delays are most commonly considered to be an atypical presentation and waiting for investigations, such as lumbar puncture [31]. Some participants may not have had signs of meningitis, a hemorrhagic rash, or septicemia at their initial presentation. In two cases, neck stiffness and rashes were present but not conveyed to the treating doctor by the AYAs, suggesting some of the questions needed for an accurate assessment of IMD were not asked, nor was a thorough physical assessment conducted. A Dutch study demonstrates that the classic triad of fever, neck stiffness, and altered mental status is commonly fully not present in adults with community-acquired bacterial meningitis. They reported that 95% of their cohort had at least two of the four symptoms of headache, fever, neck stiffness, or altered mental status [13]. In this study, most of the delays were reported after presenting to a primary healthcare setting. Quality improvement processes for primary and acute care should be initiated or continued to improve the management of meningitis and acute sepsis cases [34].

Almost all of the participants in this study were hospitalized prior to a nationally funded MenACWY adolescent school vaccination program that has run since 2019. In South Australia, a state-funded MenB school immunization program for South Australian adolescents was launched in February 2019 [35], with Queensland commencing a program in 2024 [36]. Maintaining high vaccination coverage against IMD, tailored to the local epidemiology and burden, is considered the number one strategy for improving the outcomes for risk groups [32].

The participants described the HRQoL issues they experienced during their hospitalization as well as beyond their acute infection, including the traumatic elements of the disease, described as often having inadequate follow-up. The disease sequelae identified by the participants following hospitalization in our study spanned across the physical, emotional, and social aspects of HRQoL. They included pain, fatigue, difficulty concentrating, persistent headaches, a lack of motivation, poor mood, changes to hobbies, the inability to work, and changes to relationships with family and friends, among others. These experiences are consistent with the published literature and our clinical understanding of IMD sequelae and adds to our understanding of the HRQoL impacts of IMD [4]. Further qualitative and quantitative research exploring HRQoL issues in AYAs hospitalized for IMD could be conducted to help generate further understanding of the disease’s effects and promote a more holistic approach to research, as well as disease prevention and management.

Experiencing IMD during adolescence can have a particularly negative impact on a person’s HRQoL. Pain, fatigue, depression, and low motivation limit people’s ability to engage with work, education, and training, as well as limiting how people socialize. If unaddressed, these can present as issues for people long after hospitalization and potentially negatively impact their HRQoL for the remainder of their lives. Therefore, there should be some consideration of how IMD cases are managed after they have been discharged from hospital. The participants in this study identified the lack of follow-up and information regarding their recovery as an area of unmet need. Interventions aiming to empower people post-hospitalization and manage their recovery may help reduce the distress caused by the fear of the unknown and improve HRQoL [37]. All AYAs admitted with IMD should be given an individual plan for future care, regardless of their condition at discharge. Detailed information should be provided to their GP, who can assist with support and recovery and play a key role in assisting their return to study or work after the acute phase of their illness.

There is no disease-specific HRQoL instrument for AYAs hospitalized with IMD. Such an instrument could be used within hospitals and general practice to screen for those with significant deficits in their HRQoL and identify patients requiring ongoing care. Additionally, an IMD-specific HRQoL instrument could benefit future research aiming to understand better the impact of HRQoL on AYAs who become hospitalized due to IMD. Barriers to using HRQoL instruments within clinical practice have been documented at the patient, clinician, and service levels due to time constraints, unfamiliarity with patient-reported outcome measures, and a lack of infrastructure to support ongoing HRQoL measurements [38]. Despite these barriers, there is still an opportunity for future research to develop and test disease-specific instruments for IMD to aid future clinical care and research efforts.

Negative HRQoL impacts also need to be considered for the parents and caregivers of adolescents diagnosed with IMD. It is well documented that carers of people with significant illnesses have unmet support needs, which has also been identified in carers of people hospitalized with IMD [39]. The participants in this study described their caregivers’ ongoing issues as a response to their hospitalization. Caring for their child as they experience potential morbidity and mortality can impact a carer’s social and emotional functioning. A Delphi study highlighted the importance of considering not just the QoL losses experienced directly by patients but also the effects on their families, especially for 6–18-year-olds, where the impact on parents and siblings is particularly significant [40]. In this study, we only have the perspectives of the IMD cases. However, many were concerned about the effects of their illness on their immediate family. There may be a need for post-IMD infection interventions for caregivers to manage these feelings and improve their emotional functioning, as carried out for carers of patients with other diseases [41,42]. Furthermore, the clinical management of patients with IMD could consider shifting towards a multidisciplinary approach, where patients are treated during their acute infection but are also provided the opportunity for follow-up services that address the concerns of patients and carers beyond their hospitalization. This multidisciplinary approach has proven effective in other conditions, such as cancer [43], and may help center HRQoL in treating patients with IMD.

IMD can be a distressing experience for AYAs and their caregivers, with ongoing HRQoL impacts. Despite being a vaccine-preventable disease, many countries do not include a publicly funded meningococcal vaccine program for adolescents or have limited access to meningococcal vaccines [25]. However, there is some evidence supported by the findings of our study to indicate that the longer-term disease burden of IMD has been underestimated [25]; thus, a detailed and coordinated collection of disease burden data is warranted to better inform public vaccination policy for meningococcal disease.

Limitations

Our research demonstrates that patients who are diagnosed with IMD may experience long-term HRQoL implications as a result of the disease. Due to the nature of qualitative research, our sample’s experiences are unlikely to broadly represent patients with IMD, particularly as the participants were recruited from two Australian states: South Australia and Victoria. To further understand the burden of IMD, our data should be combined with quantifiable clinical and patient-reported data from across Australia to understand better the societal and economic impact of IMD, which better informs disease prevention and management. The research participants were primarily from the least disadvantaged decile in terms of socioeconomic disadvantage. In countries similar to Australia, this is a common problem, with socially disadvantaged groups often under-represented in research [44]. Our results may not fully capture the intersection between IMD and socioeconomic disadvantage. Further research targeting more disadvantaged socioeconomic groups would be needed to investigate whether this cohort has unique experiences requiring specialist intervention and support.

5. Conclusions

Seven themes relating to the participants’ experience of IMD were identified in this analysis. They identified some barriers to seeking timely healthcare access. They also identified the profound impact IMD had on the adolescents and their families, including a lingering impact on their quality of life for some. Post-discharge care was highlighted as an area that could be enhanced for AYAs following discharge.

A multifaceted approach should be considered to improve the experience and outcomes for AYAs with IMD. These approaches should include (a) improving early detection through increasing awareness of the key IMD symptoms for AYAs and continuing education and conducting quality improvement processes for primary and acute care to ensure the timely management of meningitis and sepsis, (b) developing follow-up care plans based on HRQoL screening of AYAs at discharge, (c) ensuring these plans include the input of members of a multidisciplinary team, and (d) conducting a questionnaire or follow-up with the parents and caregivers of AYAs to gain additional insights into the family experience with meningococcal disease, which could enhance care.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/healthcare12111075/s1. AMEND Semi-Structured Interview Schedule.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.S.M.; methodology, M.M., J.M., J.B., D.S., D.G. and H.S.M.; formal analysis, J.M.; investigation, M.M., M.A., L.S. and S.M.M.; resources, D.S., D.G., M.S.W., R.N. and R.H.; data curation, M.M. and J.M.; writing—original draft, J.M.; writing—review and editing, all authors; project administration, M.M., M.A., J.B., L.S., M.S.W., R.N. and R.H.; funding acquisition, H.S.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors declare that this study received funding from Pfizer. The funder had the following involvement with the study: a review of the study protocol. The funder was not involved in the study design, collection, analysis, interpretation of data, the writing of this article or the decision to submit it for publication.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of the Women’s and Children’s Health Network (HREC/14/WCHN/024; approval date: 10 June 2014) and Monash Health (16093A; approval date: 13 May 2016).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all the subjects involved in the study. Written informed consent for publication was waived because there is no identifying information.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study may be made available on request by the corresponding author. Individual participant data (IPD) will be provided on a case-by-case basis at the discretion of the study investigators and the WCHN HREC to maintain confidentiality. Access to IPD will be granted solely for the purposes outlined in the approved proposal.

Acknowledgments

We want to thank the participants who shared their experiences and insights.

Conflicts of Interest

H.S.M. is an investigator of vaccine trials sponsored by industry (the GSK group of companies, Novavax, Pfizer). H.S.M.’s, S.M.M.’s M.M.’s, J.B.’s, L.S.’s, and J.M.’s respective institutions receive funding for investigator-led studies (including from Pfizer, Sanofi-Pasteur, and the GSK group of companies). H.S.M., S.M.M., M.M., J.B., L.S., and J.M. receive no personal payments from industry. R.N. is an investigator of trials sponsored by industry (Astra Zeneca, Medpace Armata Pharmaceuticals). R.N. does not receive any personal payments from industry. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of the data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Hart, C.A.; Thomson, A.P. Meningococcal disease and its management in children. BMJ (Clin. Res. Ed.) 2006, 333, 685–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baker, C.J. Prevention of Meningococcal Infection in the United States: Current Recommendations and Future Considerations. J. Adolesc. Health Off. Publ. Soc. Adolesc. Med. 2016, 59, S29–S37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edmond, K.; Clark, A.; Korczak, V.S.; Sanderson, C.; Griffiths, U.K.; Rudan, I. Global and regional risk of disabling sequelae from bacterial meningitis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2010, 10, 317–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voss, S.S.; Nielsen, J.; Valentiner-Branth, P. Risk of sequelae after invasive meningococcal disease. BMC Infect. Dis. 2022, 22, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borg, J.; Christie, D.; Coen, P.G.; Booy, R.; Viner, R.M. Outcomes of meningococcal disease in adolescence: Prospective, matched-cohort study. Pediatrics 2009, 123, e502–e509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viner, R.M.; Booy, R.; Johnson, H.; Edmunds, W.J.; Hudson, L.; Bedford, H.; Kaczmarski, E.; Rajput, K.; Ramsay, M.; Christie, D. Outcomes of invasive meningococcal serogroup B disease in children and adolescents (MOSAIC): A case-control study. Lancet Neurol. 2012, 11, 774–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, K.L.; Bell, T.J.; Miller, J.M.; Misurski, D.A.; Bapat, B. Hospital costs, length of stay and mortality associated with childhood, adolescent and young adult meningococcal disease in the US. Appl. Health Econ. Health Policy 2011, 9, 197–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lahra, M.M.; Enriquez, R.P. Australian Meningococcal Surveillance Programme annual report, 2014. Commun. Dis. Intell. Q. Rep. 2016, 40, E221–E228. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pelton, S.I. The Global Evolution of Meningococcal Epidemiology Following the Introduction of Meningococcal Vaccines. J. Adolesc. Health Off. Publ. Soc. Adolesc. Med. 2016, 59, S3–S11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keshavan, M.S.; Giedd, J.; Lau, J.Y.; Lewis, D.A.; Paus, T. Changes in the adolescent brain and the pathophysiology of psychotic disorders. Lancet Psychiatry 2014, 1, 549–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sander, J.; Bay, D.; Gedde-Dahl, T.W.; Borchgrevink, H.M.; Froholm, L.O.; Oftedal, S.I.; Vandvik, B. Late sequelae after meningococcal disease. A controlled study in young men. NIPH Ann. 1984, 7, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Young, N.; Thomas, M. Meningitis in adults: Diagnosis and management. Intern. Med. J. 2018, 48, 1294–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van de Beek, D.; de Gans, J.; Spanjaard, L.; Weisfelt, M.; Reitsma, J.B.; Vermeulen, M. Clinical features and prognostic factors in adults with bacterial meningitis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2004, 351, 1849–1859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lepur, D.; Barsic, B. Community-acquired bacterial meningitis in adults: Antibiotic timing in disease course and outcome. Infection 2007, 35, 225–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelton, S.I. Meningococcal Disease Awareness: Clinical and Epidemiological Factors Affecting Prevention and Management in Adolescents. J. Adolesc. Health 2010, 46, S9–S15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, M.J.; Ninis, N.; Perera, R.; Mayon-White, R.; Phillips, C.; Bailey, L.; Harnden, A.; Mant, D.; Levin, M. Clinical recognition of meningococcal disease in children and adolescents. Lancet 2006, 367, 397–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Santoreneos, R.; Giles, L.; Haji Ali Afzali, H.; Marshall, H. Case fatality rates of invasive meningococcal disease by serogroup and age: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Vaccine 2019, 37, 2768–2782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eisen, D.P.; Hamilton, E.; Bodilsen, J.; Koster-Rasmussen, R.; Stockdale, A.J.; Miner, J.; Nielsen, H.; Dzupova, O.; Sethi, V.; Copson, R.K.; et al. Longer than 2 hours to antibiotics is associated with doubling of mortality in a multinational community-acquired bacterial meningitis cohort. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinberger, J.; Rhee, C.; Klompas, M. A Critical Analysis of the Literature on Time-to-Antibiotics in Suspected Sepsis. J. Infect. Dis. 2020, 222, S110–S118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Centre for Disease Prevention Control. Expert Opinion on the Introduction of the Meningococcal B (4CMenB) Vaccine in the EU/EEA. Available online: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications-data/expert-opinion-introduction-meningococcal-b-4cmenb-vaccine-eueea (accessed on 9 April 2024).

- Wallace, M.; Harcourt, D.; Rumsey, N. Adjustment to appearance changes resulting from meningococcal septicaemia during adolescence: A qualitative study. Dev. Neurorehabilit. 2007, 10, 125–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orbell, S.; Schneider, H.; Esbitt, S.; Gonzalez, J.S.; Gonzalez, J.S.; Shreck, E.; Batchelder, A.; Gidron, Y.; Pressman, S.D.; Hooker, E.D.; et al. Health-Related Quality of Life. In Encyclopedia of Behavioral Medicine; Gellman, M.D., Turner, J.R., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 929–931. [Google Scholar]

- Stevens, K.; Palfreyman, S. The use of qualitative methods in developing the descriptive systems of preference-based measures of health-related quality of life for use in economic evaluation. Value Health 2012, 15, 991–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McHorney, C.A.; Ware, J.E., Jr.; Lu, J.F.; Sherbourne, C.D. The MOS 36-item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36): III. Tests of data quality, scaling assumptions, and reliability across diverse patient groups. Med. Care 1994, 32, 40–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marshall, H.; McMillan, M.; Wang, B.; Booy, R.; Afzali, H.; Buttery, J.; Blyth, C.C.; Richmond, P.; Shaw, D.; Gordon, D.; et al. AMEND study protocol: A case-control study to assess the long-term impact of invasive meningococcal disease in Australian adolescents and young adults. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e032583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fusch, P.; Ness, L. Are We There Yet? Data Saturation in Qualitative Research. Qual. Rep. 2015, 20, 1408–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. Socioeconomic Indexes for Areas (SEIFA). Available online: https://www.abs.gov.au/websitedbs/censushome.nsf/home/seifa (accessed on 9 May 2024).

- Charlson, M.E.; Carrozzino, D.; Guidi, J.; Patierno, C. Charlson Comorbidity Index: A Critical Review of Clinimetric Properties. Psychother. Psychosom. 2022, 91, 8–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sims-Schouten, W.; Riley, S.C.E.; Willig, C. Critical Realism in Discourse Analysis. Theory Psychol. 2016, 17, 101–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glimåker, M.; Johansson, B.; Grindborg, Ö.; Bottai, M.; Lindquist, L.; Sjölin, J. Adult Bacterial Meningitis: Earlier Treatment and Improved Outcome Following Guideline Revision Promoting Prompt Lumbar Puncture. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2015, 60, 1162–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO. Defeating Meningitis by 2030: A Global Road Map; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Bullen, C. Taking public health to the streets: The 1998 Auckland Meningococcal Disease Awareness Program. Health Educ. Behav. 2000, 27, 363–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guimont, C.; Hullick, C.; Durrheim, D.; Ryan, N.; Ferguson, J.; Massey, P. Invasive meningococcal disease—Improving management through structured review of cases in the Hunter New England area, Australia. J. Public Health 2010, 32, 38–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meningococcal B Immunisation Program. Available online: https://www.sahealth.sa.gov.au/wps/wcm/connect/public+content/sa+health+internet/conditions/immunisation/immunisation+programs/meningococcal+b+immunisation+program (accessed on 13 December 2023).

- Queensland MenB Vaccination Program. Available online: https://www.health.qld.gov.au/clinical-practice/guidelines-procedures/diseases-infection/immunisation/meningococcal-b (accessed on 5 April 2024).

- Wisemantel, M.; Maple, M.; Massey, P.D.; Osbourn, M.; Kohlhagen, J. Psychosocial Challenges of Invasive Meningococcal Disease for Children and their Families. Aust. Soc. Work. 2018, 71, 478–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.; Butow, P.; Dhillon, H.; Sundaresan, P. A review of the barriers to using Patient-Reported Outcomes (PROs) and Patient-Reported Outcome Measures (PROMs) in routine cancer care. J. Med. Radiat. Sci. 2021, 68, 186–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olbrich, K.J.; Muller, D.; Schumacher, S.; Beck, E.; Meszaros, K.; Koerber, F. Systematic Review of Invasive Meningococcal Disease: Sequelae and Quality of Life Impact on Patients and Their Caregivers. Infect. Dis. Ther. 2018, 7, 421–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marten, O.; Koerber, F.; Bloom, D.; Bullinger, M.; Buysse, C.; Christensen, H.; De Wals, P.; Dohna-Schwake, C.; Henneke, P.; Kirchner, M.; et al. A DELPHI study on aspects of study design to overcome knowledge gaps on the burden of disease caused by serogroup B invasive meningococcal disease. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2019, 17, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woolf, C.; Muscara, F.; Anderson, V.A.; McCarthy, M.C. Early Traumatic Stress Responses in Parents Following a Serious Illness in Their Child: A Systematic Review. J. Clin. Psychol. Med. Settings 2016, 23, 53–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yi-Frazier, J.P.; Fladeboe, K.; Klein, V.; Eaton, L.; Wharton, C.; McCauley, E.; Rosenberg, A.R. Promoting Resilience in Stress Management for Parents (PRISM-P): An intervention for caregivers of youth with serious illness. Fam. Syst. Health J. Collab. Fam. Healthc. 2017, 35, 341–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, C.; Shewbridge, A.; Harris, J.; Green, J.S. Benefits of multidisciplinary teamwork in the management of breast cancer. Breast Cancer (Dove Med. Press) 2013, 5, 79–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonevski, B.; Randell, M.; Paul, C.; Chapman, K.; Twyman, L.; Bryant, J.; Brozek, I.; Hughes, C. Reaching the hard-to-reach: A systematic review of strategies for improving health and medical research with socially disadvantaged groups. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2014, 14, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).