Abstract

Nursing students’ integration of theoretical knowledge and practical abilities is facilitated by their practice of nursing skills in a clinical environment. A key role of preceptors is to assess the learning goals that nursing students must meet while participating in clinical practice. Consequently, the purpose of this study was to explore the current evidence in relation to competency assessment and assessment approaches, and the willingness of preceptors for assessing nursing students’ competency in a clinical setting. The scoping review used the five-stage methodological framework that was developed by Arksey and O’Malley, as well as the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Extension for Scoping Reviews. Relevant studies were searched by applying a comprehensive literature search strategy up to April 2024 across the following databases: CINAHL, OVID MEDLINE, EMBASE, and PUBMED. A total of 11,297 studies published between 2000 and April 2024 were revealed, and 38 were eligible for inclusion, which the research team categorised into three main themes: definitions of competence, tools for assessing competence and preceptors’ and mentors’ viewpoints in relation to the assessment of nursing students’ competence. This review established that there are a multitude of quantitative instruments available to assess clinical competence; however, a lack of consistency among assessment instruments and approaches between countries and higher education institutions is prevalent. Existing research evidence suggests that the preceptors carried out the assessment process clinically and they found difficulties in documenting assessment. The assessing of nursing students’ competency and the complexity of assessment is a concern for educators and mentors worldwide. The main concern centers around issues such as the interpretation of competence and complex measurement tools.

1. Introduction

Clinical assessment is an important issue in clinical nursing education programmes. Assessment provides an opportunity for nursing students to acquire the required knowledge through practice and assessment in a variety of clinical settings [1,2]. Clinical practice assists nursing students in improving nursing skills and adapting them to a variety of professional roles and clinical places [2]. Further, it contributes to the integration of theoretical knowledge and clinical skills for nursing students [2].

Most nursing scholars Expressed a broad view of competence as a virtue, as well as knowledge. Competence contains broad features that pertain to the capacity to carry out a task under various conditions and provide desired results [3,4]. It is further accomplished through good abilities, skills, attitudes, and values in the same line with ethical behaviour and the effective delivery of quality services [5,6,7,8]. Nursing competence is a crucial capability required to realise the responsibilities of nursing. Therefore, it is important to clearly define the concept of nursing competence and establish a fundamental definition for nursing education curricula. It would be helpful to understand how nurses develop competence in order to enhance continuous professional development and to support improvements in nursing quality [9].

Efficient mentoring in clinical environments assists nursing students in promoting the required competence and improving the integration of theory and practice [10]. The mentoring of nursing students is performed by nursing staff known as ‘nursing preceptors’ in Saudi Arabia (SA) [11], Ireland [12], and in the United States and Sweden [13]. They are known in the United Kingdom as ‘nursing mentors’ [14], and as ‘buddy nurses’ in Australia [15].

Nursing preceptors have a significant role in clinical nursing education. The role of nursing preceptors in clinical nursing education includes supervising nursing students who are enrolled in a rigorous clinical practicum program [16]. Among the responsibilities of nursing preceptors is guiding nursing students through the integration of theoretical knowledge into clinical practice, guiding and teaching practical nursing skills, and improving skills of problem-solving and critical thinking [17]. Preceptors are further included in assessing nursing students’ competence [18]. They have an essential responsibility in assessing the learning outcomes that must be fulfilled by nursing students in clinical environments [19].

Considering the importance of the preceptors’ roles, it might be helpful to explore how nursing preceptors view the assessment of competence. This would increase perception of the significance of competence assessment strategies in the nursing field and thus contribute to making the outcomes of nursing program more eligible and qualified.

It is essential to assess the competence of nursing students with professional practitioners in order to examine whether nursing students have developed sufficient competence levels for providing safe nursing care to patients [20,21,22]. Performance-based systems can be used to assess competency by using a variety of tools and allowing students to achieve certain levels of competence [21,22,23]. Using a valid assessment competence tool may be helpful in promoting and developing good-quality nursing education [24].

The complexity of assessing competence is still a concern for nursing educators and preceptors [22]. There is inconsistency in terms of assessment approaches and instruments [17] and a lack of validity and reliability of assessment instruments for measuring competence in clinical practice [25]. Part of the nurse preceptor’s role is to assess the competence of nursing students in order to make them ready for professional responsibilities and future tasks. However, preceptors find it difficult to assess students’ competencies in an objective manner [2,18,26]. Moreover, they encounter several challenges during the assessment of nursing students’ competencies, including responsibilities associated with conflict, work stress, overload work, and ambiguity of assessment documents [16,27].

The aim of the scoping review is to explore the current evidence in relation to competency assessment and assessment approaches, and the willingness of preceptors for assessing nursing students’ competency in clinical setting.

2. Materials and Methods

A scoping review is a response to a particular methodology that involves identifying and evaluating previous research on a certain subject based on predetermined eligibility standards. The purpose of the scoping review is to summarise, analyse, and report the findings that clearly address a particular research question. A preliminary search of the International Databases to registered Systematic Reviews such as PROSPERO, OSF, and INPLASY® did not identify any reviews on the topic. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2020 guidelines were adopted for this study due to their applicability, as they are primarily intended to assess systematic reviews of studies, irrespective of the included studies’ designs [28,29]. Specifically, this scoping review was conducted using the PRISMA extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) checklist [29]; the scoping review’s protocol has been registered at Open Science Framework (OSF).

The methodology of the scoping review included the five-stage methodological framework that is designed by Arksey and O’Malley (2005) [30] and then advanced by Levac et al. (2010) [28]. These five stages are: (1) identifying the research question, (2) identifying relevant studies, (3) study selection, (4) charting the data, and (5) collating, summarising, and reporting the results [28,31]. The guidelines of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) checklist was followed to ensure rigour in reporting the results of the study [29].

2.1. Identifying the Research Questions

To achieve the aim of this scoping review, the following research questions were formulated after using the PCC framework: 1. What are the definitions of competence? 2. What are tools used for assessing competence? 3. What are the viewpoints of nursing preceptors and mentors regarding the assessment of competence?

2.2. Identifying Relevant Studies

After the research questions were created, in order to optimise the evidence recovered from the databases, the search strategy of the literature was based on the PCC frame-work, involving the dividing of the research question in accordance with the components that follow: Population (P), Concepts (C) and Context (C). Table 1 presents the PCC model:

Table 1.

The PCC model.

An analysis of the research questions’ terms was carried out to help guide the scoping review’s search strategy according to the PCC framework. A comprehensive list of terms was created for the research strategy in consultation with a research team and a nursing librarian after identifying them according to the terms MeSH (Medical Subject Headings) and DeCS (Health sciences desCriptors). The search strategy was conducted using the terms and the relevant synonyms were identified as follows in Table 2.

Table 2.

Terms and the relevant synonyms.

Relevant studies were searched by applying a comprehensive literature search strategy up to April 2024 across the following four databases: CINAHL, OVID MEDLINE, EMBASE, and PUBMED. Time limitations during the study searching were set for the last 5 years, then extended to 10, 15 and finally 20 years, however, there were no studies older than 15 years that met the inclusion criteria. Further, restricting the search date is a legitimate and fast way to provide reliable information for prompt decision-making. Xu et al. (2021) [32] conducted a study to investigate the accuracy and workload of search date limitations, and the search results and the results identified fell within a maximum tolerance of 5% and 10% for magnitude bias, indicating that a limitation on the last 20 years can save the most effort while still achieving high accuracy. The databases were selected with the goal of locating studies pertinent to the topic of the scoping literature review, and the reasons for choosing these databases was because of their widespread interdisciplinary coverage and worldwide renown. Furthermore, a manual search of the reference lists of eligible studies was also used. Studies containing descriptors linked to the terms MeSH (Medical Subject Headings) and DeCS (Health sciences desCriptors) were chosen based on the eligibility criteria. The MeSH and DeCS descriptors were used to identify the terms Preceptors, Competency, and Nursing. These terms and their synonyms were then combined with a Boolean operator to create a database search that would accomplish the proposed objectives. The searches with descriptors and Boolean AND and OR operators are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Search with descriptor and Boolean AND/OR operators.

The scoping review was conducted through many stages including organising, summarising, and integrating the findings from various studies to develop a coherent understanding of the competency assessment in clinical practice. The research team commenced by identifying common themes, patterns, and gaps in the included studies. Then, they created a table, and highlighted the key findings to present the information effectively. Finally, they ensured the synthesis was clear, concise, and accurately represented the breadth of the literature that were reviewed.

2.3. Study Selection

Studies were selected according to inclusion and exclusion criteria. Inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) All studies concerning the nursing assessment of competence and competence. (2) Studies examining nursing preceptors’ experiences in the nursing assessment of competence and their perspectives of making decisions in relation to the assessment of nursing students’ competence. (3) Studies which identified present instruments or had a developed instrument for assessing nursing students’ competence. (4) Peer-reviewed studies that have full text, open access studies and those published in academic journals and in the English language from 2000–2024, (5) Peer-reviewed reviews including systematic, scoping, narrative, and integrative reviews. The exclusion criteria in this scoping review were as follows: (1) Studies concerning assessment of healthcare students’ competence. (2) Studies concerning the perspectives of nursing educators and nursing students in relation to assessment of competence. (3) Conference abstracts, posters, and opinion studies. The benefit of a scoping review is that it offers the opportunity to include all types of studies, and so these are included in the interest of thoroughness.

2.4. Charting the Data

The studies that met the inclusion criteria were uploaded into the reference manager Mendeley, and this application was used to remove duplicated studies. Included studies were downloaded into the Mendeley application to remove duplication. The process of data analysis started with the first author using a data extraction form and inputting the data into an Excel spreadsheet. The following categories were created to extract the data for each of the included studies, when eligible: Author(s), year, aim, country of the study, key words, study design, participants (sample or number of studies), instruments, and key findings that relate to the scoping review objectives, and these were then reviewed and verified by the research team.

2.5. Collating, Summarising, and Reporting the Results

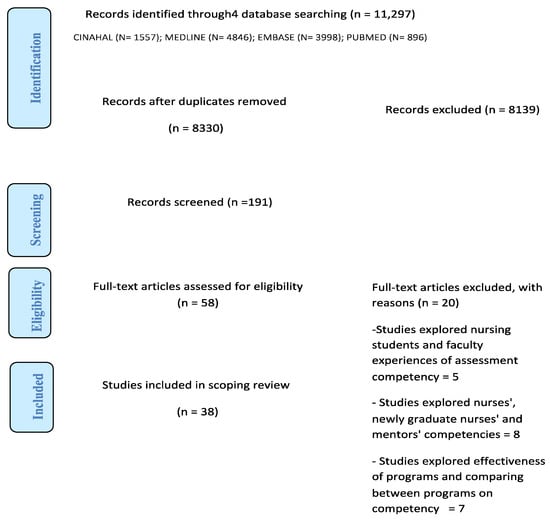

There were 11,297 studies found in the initial search results across all databases. One author initially reviewed the titles and abstracts; 191 studies were included while 8043 were excluded. One author conducted a second screening of these 191 studies’ titles and abstracts, and 58 studies were included. The 58 studies’ titles and abstracts were also reviewed by the research team and 20 studies did not meet the inclusion criteria, so were excluded. The first author retrieved the full texts of the included 38 studies and the research team reviewed the data extraction tables independently. The research team categorised the 38 studies into 3 main themes. The results of the literature search and study screening process are presented in the PRISMA-ScR flow diagram [29] in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

PRISMA Flow Diagram [33].

3. Results

3.1. Overview of Included Studies

Description of Studies

This scoping review included thirty-eight research studies published between 2008 and 2023 (Table 4). These studies took place in 19 countries: Ireland (n = 8), Australia (n = 5), UK (n = 3), with two studies in each of the following countries: Finland, Singapore, Korea, Taiwan, and USA and one study in each of the following countries: Sweden, Spain, Slovenia, Turkey, Japan, China, Thailand, Jorden, Iran, and New Zealand. Two studies were conducted in both Australia and Canada (Table 5). These studies used multiple research designs; a total of 15 were quantitative research studies, 6 were qualitative research studies, 5 were mixed methods research studies, and 12 were literature reviews. Nearly half of the studies (n = 17) used questionnaires as data collection methods, whereas 9 studies employed individual or focus group interviews as methods for data collection. The participants were diverse, including preceptors, nurses, mentors, clinical assessors, clinical educators, nursing teachers, practice educators, and nursing students.

Table 4.

(1) Definitions of competence (4 studies). (2) Identification of existing tools OR specific tools that are developed for assessing competencies and Evaluation of specific tools that are developed for measuring clinical nursing assessment competency (18 studies). (3) Preceptors and Mentors Viewpoints (16 studies).

Table 5.

Summary of the countries in which the research took place.

The themes category as follows: definitions of competence, tools for assessing competence, and preceptors’ and mentors’ viewpoints in relation to the assessment of nursing students’ competence. Following data extraction, the data were then mapped against the three stated research questions. For example, question one sought to define competence. Four studies [9,34,35,36] contributed to this, and their findings are presented below. Question two sought to identify the tools which are used for assessing competence. Eighteen studies [22,24,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52] contributed to find existing tools that were used to assess competency, as well as specific assessment competence tools developed for this purpose. Question three sought to examine preceptors’ and mentors’ viewpoints related to the assessment of nursing students’ competence. Sixteen studies [2,12,18,21,25,27,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62] contributed to examining this.

3.2. The Definitions of Competence

In this scoping review, four of the included studies provided definitions of competence [9,34,35,36] and these varied based on the extensive literature review, Nehrir et al. (2016) [34] stated that nursing students’ competency is ‘‘the individual experiences, dynamic process, and positive interactive social and beneficial changes in the equality of one’s professional life that cause meta-cognitive abilities, touch reality, motivation, decision making, job involvement, professional authority, self-confidence, knowledge and professional skills”. Mrayyan et al. (2023) [36] stated that in the previous literature, competency in nursing practice was defined by knowledge, self-evaluation, and dynamic state. In addition, based on a Bachelor of Nursing degree course [35], competency was analysed as ‘‘the existence of a hierarchy of competencies that prioritises soft skills over intellectual and technical skills; the appearance of skills as personal qualities or individual attributes; and the absence of context in assessment”. Fukada (2018) [9] argues that the concept of nursing competency has not been fully developed. Thus, challenges remain in establishing an agreed definition and structure of nursing competency. Whilst there is no single agreed definition of competence, there is the agreement that competence includes a range of complex attributes such as theoretical and intellectual skills (e.g., knowledge and critical thinking), practical and behavioural skills (e.g., the ability to perform a skill safely and effectively), and personal and professional attributes (e.g., ethical practices and values).

3.3. Tools Are Used for Assessing Competence

The studies that explored tools used for assessing competence were analysed in two main subcategories including the identification of existing clinical nursing assessment competency tools, and the evaluation of specific tools that are developed for measuring clinical nursing assessment competency. There were diverse modes of assessing nursing competence assessment. Six studies identified the existing clinical nursing assessment competency tools [22,24,37,38,39,40] (Table 4 (2) theme 2). The last 12 studies in this category developed and evaluated specific nursing assessment competency instruments, such as the Nursing Students Competence Instrument (NSCI) [44], Advanced Practice Nursing Competency Assessment Instrument (APNCAI) [43], Amalgamated Student Assessment in Practice (ASAP) model and tool [46], Shared Specialist Placement Document (SSPD) tool [45], Australian Nursing Standards Assessment Tool (ANSAT) instrument [47], Competency Assessment Instrument [51], Nursing Practice Readiness Scale [49], Health Education Competency Scale (HECS) [48], Nurse Professional Competence (NPC) Scale [50] and the Nurse Competence Scale [52]. Whilst there are multiple different assessment competence tools across different countries, and assessment competence tools are developed based on the national standards, certifications, and licence criteria in each country, there is agreement that the tools focus on many domains, such as professional attributes, ethical practices, communication and interpersonal relationships, nursing processes, and critical thinking and reasoning. Also, using a valid assessment competence tool to assess certain levels of competence in students. This would be helpful in promoting and developing good-quality nursing education and achieving certain levels of competence.

3.4. The Viewpoints of Nursing Preceptors and Mentors of Assessment of Competence

This theme discussed the preceptors’ and mentors’ viewpoints of the assessment of competence in relation to preceptors’ experiences of the competency assessment process, the preceptors’ challenges of the competency assessment process, and mentor judgements and preceptors’ decision-making process/failing. Ten studies explored nursing preceptors’ perspectives of assessment competency in various research methods [2,18,21,25,53,54,55,56,57,62]. The preceptors indicated that they found difficulties in understanding the language used in the document for assessing competence. The wording lacked clarity and needed to be defined. Also, the need for a valid and reliable clinical assessment tool was required from preceptors. Two studies explored the challenges that nursing preceptors face during assessing the nursing competence [21,27]. These two studies’ findings reported that there are challenges face preceptors during the assessment process, such as difficulties in the language used for describing competencies; distinguishing among competency levels; the lack of constructive and clear feedback to nursing students; and the lack of transparent and explicit criteria, hinders the accurate and fair assessment of students. Further, numerous preceptors were inexperienced, did not completely understand the assessment procedure, and did not use all of the required assessment techniques while assessing students in clinical practice. Four studies considered preceptors’ decision-making process and mentor judgements for assessing nursing students’ competence [58,59,60,61]. Whilst the findings of the preceptors’ experiences about the assessment competence are indicated from preceptors from different countries, in various studies, and several clinical environments, there is agreement that the role of preceptors is complicated and they face challenges during the preceptorship process.

4. Discussion

The scoping review aimed to explore the existing evidence regarding the assessment of competence and assessment methods, and the preparedness of nursing preceptors to assess the competency of nursing students in clinical practice. The scoping review, comprising 38 studies, examined definitions of competence, assessment tools in current use, and the viewpoints of nursing preceptors and mentors of assessment of competence.

Variations in competence definitions were evident, reflecting contextual differences in practice [34]. Despite numerous proposed definitions, clarity remains elusive, necessitating a simple and coherent definition adaptable across institutions. Consensus suggests competence comprises multifaceted qualities, including knowledge, skills, and professional attributes, in order to improve the assessment of nursing competence for preceptors and nursing students in the clinical practice in a clear method. Moreover, identifying nursing competence promotes the continuous development of professional nursing and nursing quality [9].

The competence definitions were derived from a variety of resources and instruments. These variations in the definitions of competence result in a variety of resources to describe competency, which were defined locally with a variety of competency categories. Furthermore, it has been observed that there has been a change in use of the terms ‘competency’ and ‘competence’ in the existing literature. Nehrir et al. (2016) [34] identified that the competence definitions can be varied in a variety of ways based on profession and country. However, Fukada (2018) [9] contrasts the earlier discussion, having illustrated that the competence definitions were established from the previous literature according to international standards and the literature used in international and local databases. A range of variations has already been identified in the literature regarding the definitions of competence [9,34,35,36]; however, there is a consensus that competence encompasses a wide range of intricate qualities, including knowledge and critical thinking, practical and behavioural skills (like the ability to complete a task safely and successfully), and personal and professional qualities (like moral behaviour and values).

Assessment tools for nursing competence are diverse, covering various domains such as professional attributes and critical thinking. Although these tools are developed in various countries, there is a consensus that these tools are effective in many domains, including professional attributes, ethical practices, communication and interpersonal relationships, nursing processes, critical thinking and reasoning. The tools were designed and evaluated to achieve the needs of the assessment competence for a single institution according to a specific case measured in each situation and context, as well as the purpose of the assessment [41,42,43,50,51]. However, no universally applicable method exists, with tools tailored to specific contexts and purposes. Therefore, it is observed that there is a variety in nursing assessment competence methods and tools among countries and higher education institutions [17,22,23,37,63].

Reliability and validity concerns persist, highlighting the need for standardized assessment instruments aligned with professional standards [41,42,43,45,48,49]. Ko and Yu (2019) [51] indicated that a poor content validity in studies was described in the assessment tool. This finding is contrary to Charette et al. (2020) [39], who found that there is insufficient proof on the reliability and validity of the competence tools. Ossenberg et al. (2016) [47] discussed that the validity and reliability of the Australian Nursing Standards Assessment Tool (ANSAT) needed to be assessed.

The nursing profession is an internationally recognised professional qualification. So, it would be better to establish assessment competence tools for nursing students based on agreed professional standards for ensuring the abilities of nursing students in providing safe nursing care [20]. Standardized assessment tools would facilitate comparability and transparency across healthcare settings globally, enhancing nursing graduates’ readiness for practice.

As previously stated, the majority of preceptors from different studies face challenges in converting competence documentation into measurable criteria such as knowledge, abilities, and attitudes. This was ascribed to difficulties comprehending the terminology in the competency statements, indicating that the competency assessment document should be reviewed, as should the requirement for a trained clinical guide to assist preceptors in their duties. Consequently, it is important for people who are setting up or reviewing a nursing program to consider the principles and the mechanism of assessment competence; to establish a valid and reliable clinical assessment tool to assess certain levels of competence of students, it has to be written in simple, understandable and clear language, distinguishing between various levels of competence. Assessment competence tools should be developed collaboratively between clinical and academic colleagues, and training and other support (such as continuous mentorship) also need to be put in place to enable both preceptors and nursing students to clearly understand the criteria in the tool. Also, support for preceptors should be provided to enhance the quality of assessment process and achieve students’ outcomes to a high standard.

4.1. Strengths

This review has explored assessment competence in nursing clinical practice from various aspects, including definitions of competency, tools used to assess nursing students’ competence, and the viewpoints of nursing preceptors in relation to assessment of competence. Therefore, the scoping review would cover a wide range of areas in assessment competence. Although only English language studies were included in this review, the work represents 19 countries over the past 20 years, and thus, includes an in-depth review of the literature in this area.

4.2. Limitation

This review has a limitation in that it only included studies published in English.

5. Conclusions

The results of this scoping review can be used by nurse educators to help in facilitating the competency assessment process in clinical practice from various aspects. This review provides a range of competency definitions in the nursing field and a multitude of the quantitative instruments available to assess clinical nursing students’ competence from many different countries. Further, it is important that the views of preceptors are considered because of their significant role in assessment the competency process in clinical practice with nursing students, as well as when designing tools for the assessment of competency, because assessment is critical to gather information about learning and measuring performance, which can be used to confirm the outcome and competency among nursing students, and also determines their eligibility to be placed on a professional nursing register. This would contribute to reducing the complexity of the assessment competency faced by nursing educators and preceptors worldwide.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.A.A., I.W., M.T. and K.R.; methodology, W.A.A., I.W., M.T. and K.R.; software, W.A.A., I.W., M.T. and K.R.; validation, W.A.A., I.W., M.T. and K.R.; formal analysis, W.A.A., I.W., M.T. and K.R.; investigation, W.A.A., I.W., M.T. and K.R.; resources, W.A.A., I.W., M.T. and K.R.; data curation, W.A.A., I.W., M.T. and K.R.; writing—original draft preparation, W.A.A.; writing—review and editing, W.A.A., I.W., M.T. and K.R.; visualization W.A.A., I.W., M.T. and K.R.; supervision, I.W., M.T. and K.R.; project administration, W.A.A., I.W., M.T. and K.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Getie, A.; Tsige, Y.; Birhanie, E.; Tlaye, K.G.; Demis, A. Clinical practice competencies and associated factors among graduating nursing students attending at universities in Northern Ethiopia: Institution-based cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2021, 11, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, X.V.; Enskär, K.; Pua, L.H.; Heng, D.G.N.; Wang, W. Clinical nurse leaders’ and academics’ perspectives in clinical assessment of final-year nursing students: A qualitative study. Nurs. Health Sci. 2017, 19, 287–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ten Cate, O.; Scheele, F.; Ten Cate, T.J. Viewpoint: Competency-based postgraduate training: Can we bridge the gap between theory and clinical practice? Acad. Med. 2007, 82, 542–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ääri, R.L.; Tarja, S.; Helena, L.K. Competence in intensive and critical care nursing: A literature review. Intensive Crit. Care Nurs. 2008, 24, 78–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunn, S.V.; Lawson, D.; Robertson, S.; Underwood, M.; Clark, R.; Valentine, T.; Walker, N.; Wilson-Row, C.; Crowder, K.; Herewane, D. The development of competency standards for specialist critical care nurses. J. Adv. Nurs. 2000, 31, 339–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paganini, M.C.; Egry, E.Y. The ethical component of professional competence in nursing: An analysis. Nurs. Ethics 2011, 18, 571–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takase, M.; Teraoka, S. Development of the holistic nursing competence scale. Nurs. Health Sci. 2011, 13, 396–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AlThiga, H.; Mohidin, S.; Park, Y.S.; Tekian, A. Preparing for practice: Nursing intern and faculty perceptions on clinical experiences. Med. Teach. 2017, 39, S55–S62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukada, M. CNCSS, Clinical Nursing Competence Self-Assess-ment Scale Nursing Competency: Definition, Structure and Development. Yonago Acta Med. 2018, 61, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikkonen, K.; Tomietto, M.; Tuomikoski, A.M.; Miha Kaučič, B.; Riklikiene, O.; Vizcaya-Moreno, F.; Pérez-Cañaveras, R.M.; Filej, B.; Baltinaite, G.; Cicolini, G.; et al. Mentors’ competence in mentoring nursing students in clinical practice: Detecting profiles to enhance mentoring practices. Nurs. Open 2022, 9, 593–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboshaiqah, A.; Qasim, A. Nursing interns’ perception of clinical competence upon completion of preceptorship experience in Saudi Arabia. Nurse Educ. Today 2018, 68, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cassidy, I.; Butler, M.P.; Quillinan, B.; Egan, G.; Mc Namara, M.C.; Tuohy, D.; Bradshaw, C.; Fahy, A.; Connor, M.O.; Tierney, C. Preceptors’ views of assessing nursing students using a competency based approach. Nurse Educ. Pract. 2012, 12, 346–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Löfmark, A.; Thorell-Ekstrand, I. Nursing students’ and preceptors’ perceptions of using a revised assessment form in clinical nursing education. Nurse Educ. Pract. 2014, 14, 275–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cassidy, S. Interpretation of competence in student assessment. Nurs. Stand. 2009, 23, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, A.; Eaton, E. Assisting nurses to facilitate student and new graduate learning in practice settings: What “support” do nurses at the bedside need? Nurse Educ. Pract. 2013, 13, 197–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Omansky, G.L. Staff nurses’ experiences as preceptors and mentors: An integrative review. J. Nurs. Manag. 2010, 18, 697–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cant, R.; Mckenna, L.; Cooper, S. Assessing preregistration nursing students’ clinical competence: A systematic review of objective measures. Int. J. Nurs. Pract. 2013, 19, 163–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, X.V.; Enskär, K.; Heng, D.G.N.; Pua, L.H.; Wang, W. The perspectives of preceptors regarding clinical assessment for undergraduate nursing students. Int. Nurs. Rev. 2016, 63, 473–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dobrowolska, B.; McGonagle, I.; Kane, R.; Jackson, C.S.; Kegl, B.; Bergin, M.; Cabrera, E.; Cooney-Miner, D.; Di Cara, V.; Dimoski, Z.; et al. Patterns of clinical mentorship in undergraduate nurse education: A comparative case analysis of eleven EU and non-EU countries. Nurse Educ. Today 2016, 36, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trede, F.; Smith, M. Teaching reflective practice in practice settings: Students’ perceptions of their clinical educators. Teach. High. Educ. 2012, 17, 615–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almalkawi, I.; Jester, R.; Terry, L. Exploring mentors’ interpretation of terminology and levels of competence when assessing nursing students: An integrative review. Nurse Educ. Today 2018, 69, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Immonen, K.; Oikarainen, A.; Tomietto, M.; Kääriäinen, M.; Tuomikoski, A.M.; Kaučič, B.M.; Filej, B.; Riklikiene, O.; Flores Vizcaya-Moreno, M.; Perez-Cañaveras, R.M.; et al. Assessment of nursing students’ competence in clinical practice: A systematic review of reviews. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2019, 100, 103414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helminen, K.; Coco, K.; Johnson, M.; Turunen, H.; Tossavainen, K. Summative assessment of clinical practice of student nurses: A review of the literature. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2016, 53, 308–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ličen, S.; Plazar, N. Identification of nursing competency assessment tools as possibility of their use in nursing education in Slovenia—A systematic literature review. Nurse Educ. Today 2015, 35, 602–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helminen, K.; Johnson, M.; Isoaho, H.; Turunen, H.; Tossavainen, K. Final assessment of nursing students in clinical practice: Perspectives of nursing teachers, students and mentors. J. Clin. Nurs. 2017, 26, 4795–4803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forsberg, E.; Georg, C.; Ziegert, K.; Fors, U. Virtual patients for assessment of clinical reasoning in nursing—A pilot study. Nurse Educ. Today 2011, 31, 757–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, B.; Murphy, S. Assessing undergraduate nursing students in clinical practice: Do preceptors use assessment strategies? Nurse Educ. Today 2008, 28, 301–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levac, D.; Colquhoun, H.; Brien, K.K.O. Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implement. Sci. 2010, 5, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; Brien, K.K.O.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Ma, Q.; Horsley, T.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arksey, H.; Malley, L.O.; Arksey, H.; Malley, L.O. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework Scoping Studies: Towards a Methodological Framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 5579, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.; Marnie, C.; Tricco, A.C.; Pollock, D.; Munn, Z.; Alexander, L.; McInerney, P.; Godfrey, C.M.; Khalil, H. Updated methodological guidance for the conduct of scoping reviews. JBI Evid. Synth. 2020, 18, 2119–2126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, C.; Ju, K.; Lin, L.; Jia, P.; Kwong, J.S.; Syed, A.; Furuya-Kanamori, L. Rapid evidence synthesis approach for limits on the search date: How rapid could it be? Res. Synth. Methods 2022, 13, 68–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; Group, T.P. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. J. Integr. Med. 2009, 6, 889–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nehrir, B.; Vanaki, Z.; Mokhtari Nouri, J.; Khademolhosseini, S.M.; Ebadi, A. Competency in Nursing Students: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Travel Med. Glob. Health 2016, 4, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Windsor, C.; Douglas, C.; Harvey, T. Nursing and competencies—A natural fit: The politics of skill/competency formation in nursing. Nurs. Inq. 2012, 19, 213–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mrayyan, M.T.; Abunab, H.Y.; Abu Khait ARawashdeh, S.; Algunmeeyn, A.; Saraya, A.A. Competency in nursing practice: A concept analysis. BMJ Open 2023, 13, e067352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanhua, C.; Watson, R. A review of clinical competence assessment in nursing. Nurse Educ. Today 2011, 31, 832–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charette, M.; McKenna, L.G.; Deschênes, M.F.; Ha, L.; Merisier, S.; Lavoie, P. New graduate nurses’ clinical competence: A mixed methods systematic review. J. Adv. Nurs. 2020, 76, 2810–2829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charette, M.; McKenna, L.G.; Maheu-Cadotte, M.A.; Deschênes, M.F.; Ha, L.; Merisier, S. Measurement properties of scales assessing new graduate nurses’ clinical competence: A systematic review of psychometric properties. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2020, 110, 103734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Horn, E.; Lewallen, L.P. Clinical Evaluation of Competence in Nursing Education: What Do We Know? Nurs Educ. Perspect. 2023, 44, 335–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laokhompruttajarn, J.; Panya, P.; Suikraduang, A. The Development of a Professional Competency Evaluation Model of Nursing Students. Int. J. Nurs. Educ. 2021, 13, 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manz, J.A.; Tracy, M.; Hercinger, M.; Todd, M.; Iverson, L.; Hawkins, K. Assessing Competency: An Integrative Review of The Creighton Simulation Evaluation Instrument (C-SEI) and Creighton Competency Evaluation Instrument (C-CEI). Clin. Simul. Nurs. 2022, 66, 66–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sastre-Fullana, P.; Morales-Asencio, J.M.; Sesé-Abad, A.; Bennasar-Veny, M.; Fernández-Domínguez, J.C.; De Pedro-Gómez, J. Advanced Practice Nursing Competency Assessment Instrument (APNCAI): Clinimetric validation. BMJ Open 2017, 7, e013659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahin, S.K.; Sunal, N.; Altun, I. The Development of Nursing Competencies in Student Nurses in Turkey. Int. J. Caring Sci. 2021, 14, 1908–1916. [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor, T.; Fealy, G.M.; Kelly, M.; Guinness, A.M.M.; Timmins, F. An evaluation of a collaborative approach to the assessment of competence among nursing students of three universities in Ireland. Nurse Educ. Today 2009, 29, 493–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zasadny, M.F.; Bull, R.M. Assessing competence in undergraduate nursing students: The Amalgamated Students Assessment in Practice model. Nurse Educ. Pract. 2015, 15, 126–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ossenberg, C.; Dalton, M.; Henderson, A. Validation of the Australian Nursing Standards Assessment Tool (ANSAT): A pilot study. Nurse Educ. Today 2016, 36, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hwang, H.L.; Kuo, M.L.; Tu, C.T. Health education and competency scale: Development and testing. J. Clin. Nurs. 2018, 27, e658–e667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Shin, S. Development of the Nursing Practice Readiness Scale for new graduate nurses: A methodological study. Nurse Educ. Pract. 2022, 59, 103298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardulf, A.; Nilsson, J.; Florin, J.; Leksell, J.; Lepp, M.; Lindholm, C.; Nordström, G.; Theander, K.; Wilde-Larsson, B.; Carlsson, M.; et al. The Nurse Professional Competence (NPC) Scale: Self-reported competence among nursing students on the point of graduation. Nurse Educ. Today 2016, 36, 165–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, Y.K.; Yu, S. Core nursing competency assessment tool for graduates of outcome-based nursing education in South Korea: A validation study. Japan J. Nurs. Sci. 2019, 16, 155–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, S.M.; Fang, S.C.; Hung, C.T.; Chen, Y.H. Psychometric evaluation of a nursing competence assessment tool among nursing students: A development and validation study. BMC Med. Educ. 2022, 22, 372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butler, M.P.; Cassidy, I.; Quillinan, B.; Fahy, A.; Bradshaw, C.; Tuohy, D.; O’Connor, M.; Mc Namara, M.C.; Egan, G.; Tierney, C. Competency assessment methods—Tool and processes: A survey of nurse preceptors in Ireland. Nurse Educ. Pract. 2011, 11, 298–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fahy, A.; Tuohy, D.; McNamara, M.C.; Butler, M.P.; Cassidy, I.; Bradshaw, C. Evaluating clinical competence assessment. Nurs. Stand. 2011, 25, 42–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kennedy, S.; Chesser-Smyth, P. Assessment of undergraduate nursing students from an Irish perspective: Decisions and dilemmas? Nurse Educ. Pract. 2017, 27, 95–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burke, E.; Kelly, M.; Byrne, E.; Ui Chiardha, T.; Mc Nicholas, M.; Montgomery, A. Preceptors’ experiences of using a competence assessment tool to assess undergraduate nursing students. Nurse Educ. Pract. 2016, 17, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cassidy, S.; Coffey, M.; Murphy, F. ‘Seeking authorization’: A grounded theory exploration of mentors’ experiences of assessing nursing students on the borderline of achievement of competence in clinical practice. J. Adv. Nurs. 2017, 73, 2167–2178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burden, S.; Topping, A.E.; O’Halloran, C. Mentor judgements and decision-making in the assessment of student nurse competence in practice: A mixed-methods study. J. Adv. Nurs. 2018, 74, 1078–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hughes, L.J.; Mitchell, M.L.; Johnston, A.N.B. Just how bad does it have to be? Industry and academic assessors’ experiences of failing to fail—A descriptive study. Nurse Educ. Today 2019, 76, 206–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, R.A.; Crookes, P.A. How do expert clinicians assess student nurses competency during workplace experience? A modified nominal group approach to devising a guidance package. Collegian 2017, 24, 219–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nugent, O.; Lydon, C.; Part, S.; Dennehy, C.; Fenn, H.; Keane, L.; Prizeman, G.; Timmins, F. Who is failing who? A survey exploration of the barriers & enablers to accurate decision making when nursing students’ competence is below required standards. Nurse Educ. Pract. 2020, 45, 102791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borren, J.; Brogt, E.; Andrew, C.; Milligan, K. A qualitative analysis investigating competence assessment of undergraduatenuring students. Contemp. Nurse 2023, 59, 392–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, X.V.; Enskär, K.; Lee, C.C.S.; Wang, W. A systematic review of clinical assessment for undergraduate nursing students. Nurse Educ. Today 2015, 35, 347–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).