Abstract

Assessment of (digital) health literacy in the hospital can raise staff awareness and facilitate tailored communication, leading to improved health outcomes. Assessment tools should ideally address multiple domains of health literacy, fit to the complex hospital context and have a short administration time, to enable routine assessment. This review aims to create an overview of tools for measuring (digital) health literacy in hospitals. A search in Scopus, PubMed, WoS and CINAHL, following PRISMA guidelines, generated 7252 hits; 251 studies were included in which 44 assessment tools were used. Most tools (57%) were self-reported and 27% reported an administration time of <5 min. Almost all tools addressed the domain ‘understanding’ (98%), followed by ‘access’ (52%), ‘apply’ (50%), ‘appraise’ (32%), ‘numeracy’ (18%), and ‘digital’ (18%). Only four tools were frequently used: the Newest Vital Sign (NVS), the Short Test of Functional Health Literacy for Adults ((S)TOFHLA), the Brief Health Literacy Screener (BHLS), and the Health Literacy Questionnaire (HLQ). While the NVS and BHLS have a low administration time, they cover only two domains. HLQ covers the most domains: access, understanding, appraise, and apply. None of these four most frequently used tools measured digital skills. This review can guide health professionals in choosing an instrument that is feasible in their daily practice, and measures the required domains.

1. Introduction

Every day, many patients visit their physician in, or are admitted to, the hospital. These patients usually need to read specific instructions about their visit beforehand, make decisions about treatments during their visit, and self-manage their disease after they have left the hospital. The hospital setting is complex: patients receive various health information from many different health professionals in a short period of time. Nowadays, hospital length of stay is increasingly reduced, as is the number of hospital visits [1]. As a consequence, health professionals have less time and opportunities to provide information about treatment and care and self-management becomes even more important. After a hospital admission patients receive instructions and advice which can have major consequences if not adhered to. Misunderstood information about potential complications after discharge may lead to serious consequences.

Studies have shown that there is a considerable gap between the information provided by health professionals and what patients need or can understand [2]. Especially, patients with limited health literacy have difficulties with understanding and processing health information. Health Literacy is defined as “the degree to which individuals have the ability to find, understand, and use information and services to inform health-related decisions and actions for themselves and others” [3,4]. It is estimated that almost half (47%) of Europeans have limited health literacy [5]. Having limited health literacy is associated with more hospitalizations [6,7] and a longer hospital length of stay [8,9,10]. For example, in pancreato-biliary cancer surgery the length of stay was 13.5 vs. 9 days, respectively, for patients with and without limited health literacy [11], and for colorectal surgery this difference was 5 vs. 3.5 days [9]. Additionally, poor patient self-care, insufficient adherence to medication, a higher risk of post-surgical complications and even a higher mortality rate [12,13,14] were associated with limited health literacy. For example, in colorectal surgery, the number of postoperative complications differed significantly between patients with and without limited health literacy (43.5% vs. 24.3%) [9].

Current digital developments in hospitals, and the transition from care given in hospitals to care given in the home situation require also digital health literacy skills of patients such as operating devices, navigating on the internet and formulating questions for health professionals in e-consultation [15]. Digital health literacy, as defined by the World Health Organization, is the ability to seek, find, understand, and appraise health information from electronic sources and apply the knowledge gained to address or solve a health problem. Therefore, scholars have emphasized the need for health professionals to also gain insight into the level of digital health literacy of their patients [16].

In order to support patients with limited (digital) health literacy, and to reduce these negative consequences and resulting health disparities, health professionals in hospitals should adapt their communication and education to the needs of patients. Avoiding medical terms, using pictures and animations, referring to or helping with reliable digital resources and using the teach back-method, could help patients to understand the provided health information [17,18]. Yet, to be able to adapt their communication to the (digital) health literacy level of their patients, health professionals first need to recognize and identify patients with limited (digital) health literacy.

Recognizing patients with limited (digital) health literacy can be difficult because patients are ashamed and therefore often do not spontaneously admit they have difficulties understanding the given information [9]. Moreover, health professionals often experience a high workload and as a result have limited time to identify a low (digital) health literacy level of patients. The hospital context makes this even more difficult, since patients often talk to many different care professionals in a relatively short period of time. Addressing patients’ health literacy cannot only solely depend on health professionals’ estimations or ‘gut-feelings’ but requires measurement and dialogue [19]. Unfortunately, (digital) health literacy is not often routinely measured in a hospital setting and studies have shown that patients’ (digital) health literacy level is often overestimated [19,20]. Health professionals have expressed a need for support in recognizing low (digital) health literacy, adapting communication [21]. Assessment tools for measuring (digital) health literacy level could be helpful to identify patients with limited (digital) health literacy, but should fit in the limited time available by health professionals.

Currently, there are various assessment tools available for measuring (digital) health literacy. These tools are usually not developed for use in the hospital setting. Often, administration time is rather long whereas available time in hospitals is short. Some tools are rather complex, and due to their physical or mental state, hospitalized patients may not be able to fill in elaborate questionnaires or answer questions. Therefore, more information is needed about which tools are useful in a hospital context.

Existing reviews on available instruments have been conducted, but these do not focus on the hospital context [22,23,24,25,26], or focus on specific diseases or patient groups [27,28] such as cardiovascular diseases, on targeted departments, such as the emergency department [29], or on health literacy on the organizational level [30]. To our knowledge, no review about tools to assess (digital) health literacy in patients in the hospital context is available. To consider whether tools are suitable for health professionals in hospitals, insight is needed into various characteristics of the tools, such as administration time and mode of administration (self-administered or by professional), and whether the tool consists of self-reported questions or rather of an objective assessment. Moreover, the assessment tools vary with regard to the covered domains of health literacy. Six important domains can be distinguished [2]. First, patients need to be able to find and obtain (access) health information. Second, patients need to understand the health information and, third, to appraise the information, for example to determine if the information is reliable and if it relates to their personal situation. Fourth, to communicate with health professionals, patients have to be able to apply the health information to make decisions to maintain and improve health. Fifth, patients need numeracy skills in order to look after their health, for example to manage their diets, and to take appropriate medicine doses. And finally, the current digital developments in hospitals like patient portals and telemonitoring require the digital skills of patients [31].

Assessment of (digital) health literacy can enable hospitals to raise staff awareness of limited (digital) health literacy and provide tailored interventions based on patients’ level of (digital) health literacy. Dependent on the patients’ situation and specific department, one domain may be more important to assess than another. Unfortunately, routine assessment of (digital) health literacy of patients in hospital is not yet common. One reason for this may be lack of suitable instruments. Therefore, the aims of this current review are

- To create an overview of existing assessment tools for measuring (digital) health literacy of patients in the hospital;

- To investigate the characteristics of these tools (objective vs. self-reported, mode of administration, and administration time) and the domains that are covered by the tools (access, understand, appraise, apply, numeracy and digital skills)

- To examine to what extent studies have investigated the routine assessment of (digital) health literacy in daily clinical hospital practice.

2. Methods

A scoping review was conducted following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [32]. A search in the databases’ Scopus, PubMed, Web of Science and CINAHL was conducted to identify eligible studies. The search string consisted of three search components combined by the Boolean operator AND, each containing a list of synonyms combined by the Boolean operator OR. The following key words were included in the search string: (digital) health literacy, assessment tool, and healthcare professional (Appendix A). A search string for each database was developed with support of an information specialist and can be found in Appendix B. All articles published before January 2023 were considered for eligibility. Duplicates of articles were removed.

2.1. Eligibility

Articles were included when they met the following inclusion criteria: (1) an assessment tool to measure (digital) health literacy was applied, and (2) participants were adult patients or familial caregivers, and (3) (digital) health literacy was measured in a hospital setting and (4) the article was published in English or Dutch. Excluded were (1) studies in which the used (digital) health literacy assessment tool measured only numeracy, or only literacy, mental literacy or oral literacy; (2) non-empirical studies; and (3) studies that used (digital) health literacy assessment tools that were developed only for specific patient groups (e.g., diabetes), and studies in which (digital) health literacy was only used to describe a population characteristic.

2.2. Study Selection

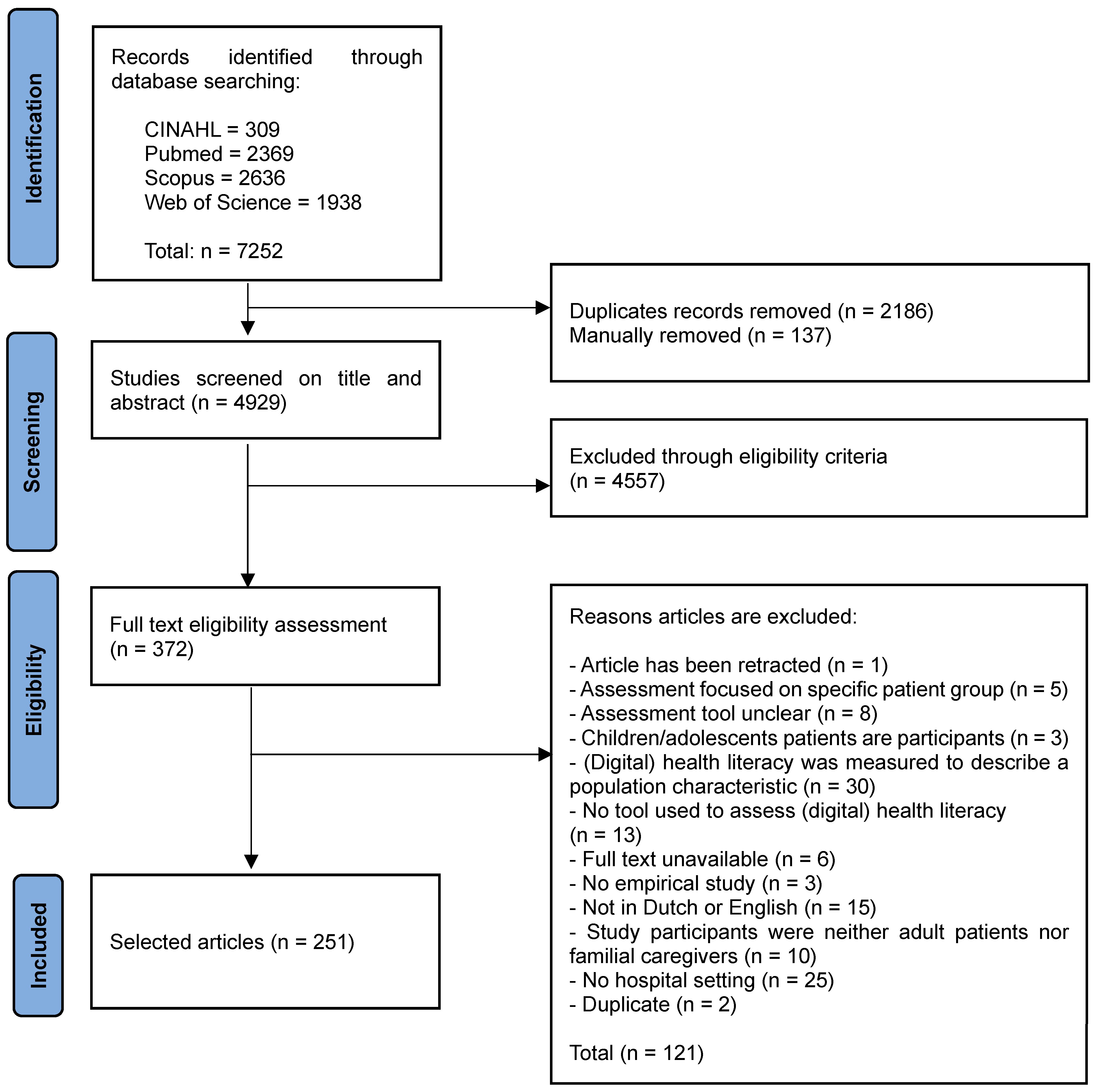

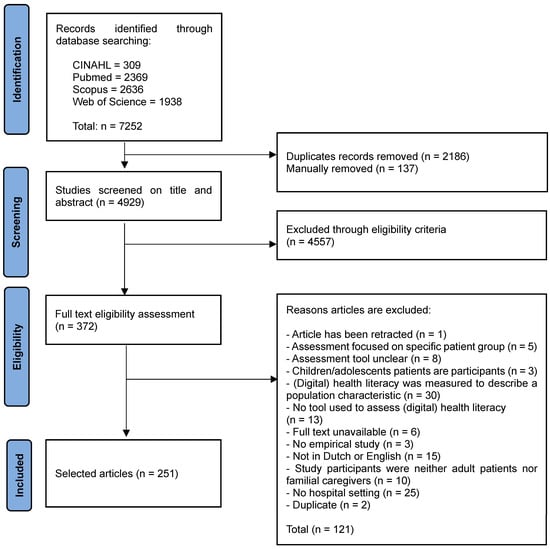

Two researchers (ED, WB) independently screened all studies for initial eligibility on the title and abstract (The PRISMA flow chart in Figure 1 summarizes the results of the search process). Differences were solved through consensus meetings. If there still was disagreement, a third and fourth researcher (CJMD, CHCD) were consulted to reach consensus. Studies included after the title and abstract screening were further assessed for eligibility through full-text reading by both ED and WB. Disagreements were resolved by discussion and, if no agreement could be reached, the third and fourth researchers were consulted.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flowchart of the search process.

2.3. Data Extraction

First, data were extracted of all the included studies regarding the year of publication, assessment tool, setting, type and number participants. Secondly, characteristics of each assessment tool were extracted, including administration time, mode of administration, objective and self-reported questions or items. Besides these characteristics, the domains measured by each assessment tool were ascertained. (Digital) health literacy can be summarized through six domains: access, understand, appraise, apply, numeracy and digital. In order to consistently assess each tool, the domains of five random tools were determined and discussed by the overall project group (ED, WB, CJMD, CHCD). After this first step, two researchers (ED, WB) determined independently for each assessment tool which domains were measured. If there was disagreement, the third and fourth researcher were consulted to reach a consensus.

3. Results

The PRISMA flow chart in Figure 1 summarizes the results of the search process. Our search generated 7252 articles. After duplicates were removed, 4929 were screened on title and abstract for eligibility, resulting in 4557 excluded articles. For the remaining 372 articles the full text was screened; 121 were excluded, mostly because (digital) health literacy was measured only for the purpose to describe a population characteristic (n = 30), no hospital setting (n = 25), not published in English or Dutch (n = 15), the article did not use an assessment tool for measuring (digital) health literacy (n = 13) or study participants were neither adult patients nor familial caregivers (n = 10). The remaining 251 articles were included in the analysis and the results of assessment tools that measured (digital) health literacy in a hospital setting are presented.

3.1. Included Studies

The 251 articles were selected. Especially in recent years, there has been an increase in number of publications: 157 (63%) articles were published in the last 5 years (2018–2022). Most studies aimed to measure the incidence of health literacy, for example in patients with diabetes, cancer and cardiac illness, or to determine an association (digital) between health literacy and another component, such as complications and length of hospital stay. The number of patients included in the studies varied broadly between 8 and 5611 patients.

3.2. Assessment Tools

In total, 44 different assessment tools for measuring (digital) health literacy were identified (Table 1). These 44 assessment tools were developed between 1991 and 2022. Tools that were most often used were the Newest Vital Sign (NVS) (n = 53 articles), the short Test of Functional Health Literacy for Adults ((S)TOFHLA) (n = 34), the Health Literacy Questionnaire (HLQ) (n = 32) and the Brief Health Literacy Screener (BHLS) (n = 28). Many of the identified assessment tools (25 out of 44) were used only occasionally, in only three or even fewer studies. Of the 44 assessment tools, fourteen were short or revised versions of an earlier developed assessment tool.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the (digital) health literacy assessment tools.

3.3. Characteristics of the Assessment Tools

The 44 assessment tools varied considerably in administration time, mode of administration (interview vs. self-report), type of assessment (objective vs. self-reported) and in the number of items or questions (Table 1). Of the 44 assessment tools, 24 (55%) did not specify the administration time. Twelve tools (27%) reported an administration time of <5 min. The SILS, BHLS, (S)BHLS and REALM-SF take only one minute to administer, in contrast to the HLS-EU-Q47, which takes over twenty minutes, the longest administration time of all tools. The mode of all assessment tools differed: some instruments were to be applied as an interview, in other instruments participants were asked to fill out a questionnaire or to perform a test. More than half of all assessment tools included only self-reported questions n = 25 (57%), meaning that participants are asked to self-assess their own skills, for example by indicating how easy or difficult they consider various tasks. Examples of these are the BHLS, SILS and HLQ. Only 17 (39%) tools used objective assessments to assess a patients’ health literacy. Examples of these are the REALM, in which patients are asked to read a list of words aloud to the health professionals, or the NVS, where patients have to answer six questions about a nutrition label. Regarding the number of items of the tool, the most concise assessment tool consists of a single item (SILS and (S)BHLS), compared to the most extensive tool that consists of 82 items or questions (Health LiTT).

3.4. Domains Measured by the Assessment Tools

The domains access, understanding, appraisal, application, numeracy and digital, which were covered by the assessment tools, are described in Table 2. Almost all tools address the understanding domain (98%). The access domain was covered by 20 (52%) tools, followed by 22 (50%) for apply, 14 (32%) for appraise, 8 (18%) for numeracy and 8 (18%) digital skills. The digital domain was added for the first time in 2006 in the assessment tool the eHEALS.

Table 2.

Domains of the (digital) health literacy assessment tools.

Regarding the number of domains included in the tools, eight assessment tools (18%) included only one domain, namely understanding, such as the REALM, SILS and PHLKS. All other tools addressed at least two (n = 11 tools), three (n = 12) or four domains (n = 9). Only three, the eHEALS, ehils and DHLI, included 5 of the 6 domains. None of the assessment tools measured all six domains.

3.5. Routine Assessment of (Digital) Health Literacy in Daily Practice in Hospitals

Out of the 251 included studies, only 4 studies reported about the routine assessment of (digital) health literacy in hospitals [111,150,254,284]. In the first study, the BHLS, a questionnaire consisting of three self-reported items, was used by 800 hospital and clinic patients and administered by nurses during routine clinical care. It demonstrated adequate reliability and validity to be used as a health literacy measure [150]. In the second study using the BHLS, health literacy was measured in 23,186 adult patients. The authors concluded that nurses in hospital and clinics adopted the new process quickly and reported it as beneficial for patient education discussions. The hospital setting had a rapid uptake of the BHLS and demonstrated sustained completion rates of more than 90% between November 2010 through April 2012 [111]. The third study [284] determined the feasibility of incorporating BHLS into EMR. Overall, nurses felt the screening was acceptable and useful. Nevertheless, some comments were noted: questions were repetitive, the patient did not understand questions or were annoyed, and nurses felt patients may not answer honestly. The last study used the REALM [254], a word recognition and pronunciation test consisting of seven items, was performed in a tertiary care academic medical center. In 1455 inpatients from nine representative floor units, the short version of the REALM was used to measure health literacy. The authors concluded that a routine health literacy assessment can be feasible and successfully implemented into the nursing workflow and electronic health record of a major academic medical center [254].

4. Discussion

When health professionals are aware of the (digital) health literacy level of their patients, health care delivery can be adapted to the needs of these patients and negative patient outcomes may be prevented. However, in hospitals the routine assessment of (digital) health literacy of patients is not common, possibly because of lack of (knowledge about) suitable instruments. This is the first scoping review that provides an overview of (digital) health literacy assessment tools used in the hospital setting. In total, 44 assessment tools were identified. Of all assessment tools, 27% reported an administration time of less than 5 minutes and 57% used self-reported questions. Almost all assessment tools addressed the domains of understanding (98%), followed by access (52%), apply (by 50%), appraise (32%), numeracy (18%) and digital skills (18%). Only four studies described routine use of (digital) health literacy in daily clinical practice in a hospital.

Despite growing interest for the topic of (digital) health literacy in the last decade, our review revealed that relatively few studies (n = 251) have examined (digital) health literacy in the specific hospital context. Thereby, more than half of these studies were published in the last five years, indicating an increasing interest for the topic. No fewer than 44 assessment tools were identified. However, 4 four tools, Newest Vital Sign, the short Test of Functional Health Literacy for Adults, the Brief Health Literacy Screener, and the Health Literacy Questionnaire, were frequently used, while 18 (41%) assessment tools were used in only one study. A strength of the Newest Vital Sign and Brief Health Literacy Screener is their relatively short administration time of <5 min. Yet, for the Newest Vital Sign reading skills are required of patients when using this assessment tool, also when the instrument is administered by a health care provider. In addition, the NVS, BHLS and the (S)TOFHLA measure only two domains. Only the HLQ include four domains: access, understand, appraise and apply. None of these four tools measure the digital skills, which is a serious disadvantage given the current digitalization in hospital care, along with tools as patient portals, e-consultations, electronic patient reported outcome measurements (ePRO’s), and devices for (home) monitoring are increasingly being used.

The assessment tools differed widely in terms of characteristics and in the domains that are assessed. With respect to administration time, almost a third of the tools took 5 min or less. In hospital care, a short administration time is crucial, because of the high workload and short time available for consultations. Thereby, also patients are not motivated to fill in long surveys [310].

Both self-reported (57%) and objective (39%) assessment tools were found in our review. Only one tool, the eHLA, included both self-reported and objective questions. Depending on the specific clinical practice, there may be a preference for an objective or self-reported assessment. Moreover, patients often need reading skills to complete these assessments. The NVS, an objective assessment tool, was used most often. Another review identified the NVS as a practical instrument to quickly assess health literacy in the absence of a more comprehensive health literacy instrument [31]. However, the acceptability of self-reported instruments for patients is probably higher because it feels less like a test [150].

With respect to the domains, almost all tools address the domain understanding (98%), followed by access (52%), apply (50%), appraise (32%), numeracy (18%) and digital (18%). None of the assessment tools covered all six domains of (digital) health literacy. Only three instruments addressed five of the six domains and almost a third included only one domain. Thus, although new instruments have been developed over the last years, there is not yet one assessment tool which includes all the domains. This indicates the difficulty of developing an assessment tool which can easily be used in a hospital by health professionals, which includes all the necessary domains and still does not require a long administration time.

Another notable finding was that only eight instruments address the digital domain. This in an era where increasingly, digital devices are implemented in hospitals, such as telemonitoring, apps, and patient portals. These innovations can contribute to a high patient engagement and improve patient outcomes. Unfortunately, to use these innovations patients need adequate digital skills. Thus, knowledge of the (lack of) digital skills of a patient may help the health professional in the decision to offer digital devices or not.

It turns out to be difficult to develop one tool that meets all the requirements of a suitable assessment tool to be used in daily clinical practice. A relatively new assessment tool, the Conversational Health Literacy Assessment tool (CHAT), provides insight into HL skills without using a long questionnaire. This assessment tool consists of 10 questions which support health professionals to engage in conversations with patients about specific health literacy strengths and challenges. The conversational approach of the CHAT promotes open communication instead of measuring what a patient is not capable of. Further evaluation of the utility and feasibility in daily practice is necessary and the digital component was still lacking.

To our knowledge, this is the first review including studies that assess the effect of the routine screening of (digital) health literacy in the hospital. Despite the importance of identifying patients with low (digital) health literacy, we found that it is still not common in daily practice. Only four studies [111,150,254,284] reported the routine assessment and registration of health literacy. Despite the importance, only four studies reported on the routine assessment of health literacy in the hospital setting. In the literature, various challenges are mentioned that can explain the paucity of studies on the topic. These include a lack of knowledge about suitable instruments and about the prevalence and consequences of low (digital) health literacy [311], a lack of belief in the benefits of assessing health literacy [311] or being afraid that discussing this delicate issue may cause shame or have a negative impact on patient engagement, trust and willingness to seek healthcare services [312], a lack of skills [312] and a lack of time [150].

Nevertheless, the four studies that were conducted all concluded that the routine assessment of health literacy is feasible, suggesting that the aforementioned challenges can be overcome. However, various limitations should be taken into account when interpreting the results of these studies. First, two of the four studies took place in the same hospital [111,150]. Second, one of the four studies was conducted in a university hospital where the educational level of patients was relatively high, limiting its generalizability [111]. Third, even though nurses in one of the studies were positive about feasibility in the questionnaire, this questionnaire was only completed by 27% [284].

Studies have reported reluctance among health care professionals towards the routine assessment of (digital) health literacy, because health literacy screening can contribute to patients feeling stigmatized and ashamed of having limited (digital) health literacy [313]. Recognizing the (digital) health literacy level of patients is important for health professionals to adapt their communication to the level of each individual patient. There are advantages and disadvantages for measuring health literacy in clinical practice. First, using an assessment tool is important because there are differences between (digital) health literacy estimation by health professionals and the actual (digital) health literacy level of patients [314]. Also, patients recognize the importance of literacy in their healthcare and most are comfortable with literacy assessment [315]. On the other hand, patients can feel ashamed and stigmatized having low (digital) health literacy.

Future research should focus on the actual use of assessment tools in daily practice and explore the facilitators and barriers of nurses in identifying patients with low (digital) health literacy. Moreover, more attention should be paid on cultural and linguistic diversity on health literacy assessment. In general, knowledge and education of available assessment tools for health professionals creates awareness and prevents negative outcomes for patients [20]. There are several training programs available for health professionals on health literacy resulting in positive outcomes on for example knowledge and skills [316]. These training programs are diverse, varying in duration, frequency and content. Some training programs also include specific education about assessment of health literacy.

However, we do not yet know if nurses in hospitals are educated, and if so, how they receive training in identifying patients with low (digital) health literacy. Insight into facilitators and barriers in using assessment tools gives the opportunity to improve communication between nurses and their patients.

This review has some notable strengths: first, the search string consists of multiple keywords to broaden the scope of the search in several databases. In addition, the data extraction was performed by two researchers, after the first five assessment tools were discussed by all four researchers to reach consensus. A limitation is that the review only included articles written in English and Dutch. Moreover, this review did not measure the quality of the included articles because the main aim was to find available assessment tools for (digital) health literacy.

5. Conclusions

This review provides an overview of available assessment tools for (digital) health literacy used in hospitals. Thereby, it provides insight into the variation in characteristics and domains included in the assessment tools. Ideally, such a tool should be able to assess several domains of health literacy including digital skills, and have a short administration time, so it can be routinely used. Currently, there is not one assessment tool that meets all these requirements and does not cause shame. We may question whether it is even possible to develop such a tool that fits all requirements. The results of this review can be used to guide health professionals in hospitals in choosing an assessment tool that is feasible in their own daily clinical practice and measures the domains that are most relevant in the particular situation. Future research should examine how the barriers for routine assessment of (digital) health literacy in the hospital can be overcome.

Author Contributions

E.M.D.: Conceptualization, methodology, validation, analysis, investigation, writing—original draft, project administration; W.W.M.t.B.: conceptualization, validation, analysis, investigation, writing—original draft; C.H.C.D.: conceptualization, writing—review and editing, supervision; C.J.M.D.: conceptualization, writing—review and editing, supervision. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by The Netherlands Organisation for Health Research and Development (ZonMw), grant number 10040022010001.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

| NVS | Newest Vital Sign |

| HLQ | Health Literacy Questionnaire |

| (S)TOFHLA | Short Test of Functional Health Literacy in Adults |

| BHLS | Brief Health Literacy Screener |

| REALM | Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Medicine |

| FCCHL | Functional Communicative Critical Health Literacy |

| eHEALS | eHealth Literacy Scale |

| SAHL (S&E) | Short Assessment of Health Literacy—Spanish & English |

| TOFHLA | Test of Functional Health Literacy for Adults |

| HLS-EU-Q47 | European Health Literacy Survey Questionnaire |

| HLS-EU-Q16 | European Health Literacy Survey Questionnaire 16 items short |

| HELIA | Health Literacy for Iranian Adults/Health Literacy Instrument for Adults |

| (S)BHLS | Short Brief Health Literacy Screener |

| REALM-R | Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Medicine—Revised |

| REALM-SF | Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Medicine—short form |

| SAHLSA_50 | Short Assessment of Health Literacy for Spanish Adults |

| SILS | Single Item Literacy Screener |

| eHLQ | eHealth Literacy Questionnaire |

| HLS-SF12 | Short Form Health Literacy Questionnaire |

| BRIEF | Brief Health Literacy Screening Tool |

| HLS(-14) | Health Literacy Scale -14 |

| Health LiTT | Health Literacy Assessment Using Talking Touchscreen Technology |

| (S)MHLS | Short-form Mandarin Health Literacy Scale |

| HELP | Health Education Literacy of patients |

| AHLS | Adult Health Literacy Scale |

| (S)KHLT | Short Form of the Korean Functional Health Literacy Test |

| EBHLS | Expanded Brief Health Literacy Screening Tool |

| PHLKS | Public Health Literacy Knowledge Scale |

| (S)Health LiTT | Short Form Health Literacy Assessment Using Talking Touchscreen Technology |

| EHILS | Everyday Health Information Literacy Screening Tool |

| (S)KHLS | Korean Health Literacy Scale short form |

| HeLMS | Health Literacy Management Scale |

| HLS | Health Literacy Scale |

| HLS-EU-Q6 | 6 items short European Health Literacy Survey Questionnaire |

| TSOY-32 | Turkish Health Literacy Scale-32 |

| (S)DHLI | Short Digital Health Literacy Instrument |

| eHLA | Electronic Health Literacy Assessment Toolkit |

| READHY | Readiness and Enablement Index for Health Technology |

| MMHLQ | Mandarin Multidimensional Health Literacy Questionnaire |

| NLP | Natural Language Processing tools |

| HLS-(19)-COM-P-Q11 | Communicative Health Literacy Survey Questionnaire |

| RIHLA | Rapid Independent Health Literacy Assessment |

| ComprehENotes | Comprehension Electronic health record Notes |

| CHAT | Conversational Health Literacy Assessment tool |

Appendix A. Search Terms

| 1 | 2 | 3 |

| “Health literacy”, “health competence”, “eHealth literacy”, “e-health literacy” “digital literacy”. | “Assessment” “assessment tool”, “questionnaire”, “scale”, “screening tool”, “survey”, “literacy screen”, “measure”, “tool”. | “Nurses”, “health care professional”, “healthcare professional”, “health care provider”, “healthcare provider”, “health care worker”, “healthcare worker”, “caregiver”, “health personnel”, “physician”, “clinical staff”, “health staff” “patient-professional communication”. |

Appendix B. Search Strings

- PubMed search string

((((((((((((nurs*[Title/Abstract]) OR (health care professional*[Title/Abstract])) OR (healthcare professional*[Title/Abstract])) OR (health care provider*[Title/Abstract])) OR (healthcare provider*[Title/Abstract])) OR (health care worker*[Title/Abstract])) OR (healthcare worker*[Title/Abstract])) OR (caregiver*[Title/Abstract])) OR (health personnel*[Title/Abstract])) OR (physician*[Title/Abstract])) OR (clinical staff*[Title/Abstract])) OR (health staff*[Title/Abstract])) OR (patient professional communication[Title/Abstract])

AND

((((((Health literacy[MeSH Terms])) OR (Health literacy[Title/Abstract])) OR (Health competence[Title/Abstract])) OR (Ehealth literacy[Title/Abstract])) OR (E-health literacy[Title/Abstract])) OR (Digital literacy[Title/Abstract])

AND

((((((((Assessment[Title/Abstract]) OR (Assessment tool[Title/Abstract])) OR (Questionnaire*[Title/Abstract])) OR (Scale[Title/Abstract])) OR (Screening tool[Title/Abstract])) OR (Survey[Title/Abstract])) OR (Literacy Screen[Title/Abstract])) OR (Measure*[Title/Abstract])) OR (Tool*[Title/Abstract])

- 2.

- Scopus search string

TITLE-ABS-KEY ((nurs* OR professional OR provider) AND (“health literacy” OR “digital literacy”) AND (“assessment tool” OR questionnaire OR survey OR “literacy scale”))

- 3.

- Web of Science search string

TS = ((nurs* OR professional OR provider) AND (“health literacy” OR “digital literacy”) AND (“assessment tool” OR questionnaire OR survey OR “literacy scale”))

- 4.

- CINAHL search string

((MH “Health Literacy”) OR “health competence” OR ehealth OR “digital literacy”) AND (assessment OR MH “Questionnaires+” OR MH “Scales” OR screening tools OR MH “Surveys+”) AND MH “Nurses+”

References

- OECD. Length of Hospital Stay (Indicator). 2023. Available online: https://data.oecd.org/healthcare/length-of-hospital-stay.htm (accessed on 24 November 2023).

- Safeer, R.S.; Keenan, J. Health literacy: The gap between physicians and patients. Am. Fam. Physician 2005, 72, 463–468. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- National Library of Medicine. An Introduction to Health Literacy. Available online: https://www.nnlm.gov/guides/intro-health-literacy (accessed on 24 November 2023).

- Sorensen, K.; Van den Broucke, S.; Fullam, J.; Doyle, G.; Pelikan, J.; Slonska, Z.; Brand, H.; Consortium Health Literacy Project, E. Health literacy and public health: A systematic review and integration of definitions and models. BMC Public Health 2012, 12, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sorensen, K.; Pelikan, J.M.; Rothlin, F.; Ganahl, K.; Slonska, Z.; Doyle, G.; Fullam, J.; Kondilis, B.; Agrafiotis, D.; Uiters, E.; et al. Health literacy in Europe: Comparative results of the European health literacy survey (HLS-EU). Eur. J. Public Health 2015, 25, 1053–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baker, D.W.; Parker, R.M.; Williams, M.V.; Clark, W.S.; Nurss, J. The relationship of patient reading ability to self-reported health and use of health services. Am. J. Public Health 1997, 87, 1027–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fabbri, M.; Murad, M.H.; Wennberg, A.M.; Turcano, P.; Erwin, P.J.; Alahdab, F.; Berti, A.; Manemann, S.M.; Yost, K.J.; Finney Rutten, L.J.; et al. Health Literacy and Outcomes Among Patients With Heart Failure: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JACC Heart Fail 2020, 8, 451–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaffee, E.G.; Arora, V.M.; Matthiesen, M.I.; Meltzer, D.O.; Press, V.G. Health Literacy and Hospital Length of Stay: An Inpatient Cohort Study. J. Hosp. Med. 2017, 12, 969–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Theiss, L.M.; Wood, T.; McLeod, M.C.; Shao, C.; Santos Marques, I.D.; Bajpai, S.; Lopez, E.; Duong, A.M.; Hollis, R.; Morris, M.S.; et al. The association of health literacy and postoperative complications after colorectal surgery: A cohort study. Am. J. Surg. 2022, 223, 1047–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berkman, N.D.; Sheridan, S.L.; Donahue, K.E.; Halpern, D.J.; Viera, A.; Crotty, K.; Holland, A.; Brasure, M.; Lohr, K.N.; Harden, E.; et al. Health literacy interventions and outcomes: An updated systematic review. Evid. Rep. Technol. Assess (Full Rep.) 2011, 199, 1–941. [Google Scholar]

- Driessens, H.; van Wijk, L.; Buis, C.I.; Klaase, J.M. Low health literacy is associated with worse postoperative outcomes following hepato-pancreato-biliary cancer surgery. HPB 2022, 24, 1869–1877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, A. Poor health literacy: A ‘hidden’ risk factor. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2010, 7, 473–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayasinghe, U.W.; Harris, M.F.; Parker, S.M.; Litt, J.; van Driel, M.; Mazza, D.; Del Mar, C.; Lloyd, J.; Smith, J.; Zwar, N.; et al. The impact of health literacy and life style risk factors on health-related quality of life of Australian patients. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2016, 14, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berkman, N.D.; Sheridan, S.L.; Donahue, K.E.; Halpern, D.J.; Crotty, K. Low Health Literacy and Health Outcomes: An Updated Systematic Review. Ann. Intern. Med. 2011, 155, 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Vaart, R.; Drossaert, C. Development of the Digital Health Literacy Instrument: Measuring a Broad Spectrum of Health 1.0 and Health 2.0 Skills. J. Med. Internet. Res. 2017, 19, e27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vollbrecht, H.; Arora, V.; Otero, S.; Carey, K.; Meltzer, D.; Press, V.G. Evaluating the Need to Address Digital Literacy Among Hospitalized Patients: Cross-Sectional Observational Study. J. Med. Internet. Res. 2020, 22, e17519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larrotta-Castillo, D.; Moreno-Chaparro, J.; Amaya-Moreno, A.; Gaitan-Duarte, H.; Estrada-Orozco, K. Health literacy interventions in the hospital setting: An overview. Health Promot. Int. 2022, 38, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, Y.R.; Huo, J.; Jo, A.; Cardel, M.; Mainous, A.G. Association of Patient-Provider Teach-Back Communication with Diabetic Outcomes: A Cohort Study. J. Am. Board Fam. Med. 2020, 33, 903–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dickens, C.; Lambert, B.L.; Cromwell, T.; Piano, M.R. Nurse overestimation of patients’ health literacy. J. Health Commun. 2013, 18 (Suppl. S1), 62–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, A. Health literacy: How nurses can make a difference. Aust. J. Adv. Nurs. 2015, 33, 20–27. [Google Scholar]

- Murugesu, L.; Heijmans, M.; Rademakers, J.; Fransen, M.P. Challenges and solutions in communication with patients with low health literacy: Perspectives of healthcare providers. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0267782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Zeng, H.; Shen, Y.; Zhang, F.; Sharma, M.; Lai, W.; Zhao, Y.; Tao, G.; Yuan, J.; Zhao, Y. Assessment Tools for Health Literacy among the General Population: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faux-Nightingale, A.; Philp, F.; Chadwick, D.; Singh, B.; Pandyan, A. Available tools to evaluate digital health literacy and engagement with eHealth resources: A scoping review. Heliyon 2022, 8, e10380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, C.Y.; Xu, R.H.; Mo, P.K.; Dong, D.; Wong, E.L. Generic Health Literacy Measurements for Adults: A Scoping Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huhta, A.M.; Hirvonen, N.; Huotari, M.L. Health Literacy in Web-Based Health Information Environments: Systematic Review of Concepts, Definitions, and Operationalization for Measurement. J. Med. Internet. Res. 2018, 20, e10273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavousi, M.; Mohammadi, S.; Sadighi, J.; Zarei, F.; Kermani, R.M.; Rostami, R.; Montazeri, A. Measuring health literacy: A systematic review and bibliometric analysis of instruments from 1993 to 2021. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0271524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, R.W.Y.; Kisa, A. A Scoping Review of Health Literacy Measurement Tools in the Context of Cardiovascular Health. Health Educ. Behav. 2019, 46, 677–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slatyer, S.; Toye, C.; Burton, E.; Jacinto, A.F.; Hill, K.D. Measurement properties of self-report instruments to assess health literacy in older adults: A systematic review. Disabil. Rehabil. 2022, 44, 2241–2257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hesselink, G.; Cheng, J.; Schoon, Y. A systematic review of instruments to measure health literacy of patients in emergency departments. Acad. Emerg. Med. 2022, 29, 890–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanobini, P.; Lorini, C.; Baldasseroni, A.; Dellisanti, C.; Bonaccorsi, G. A Scoping Review on How to Make Hospitals health Literate Healthcare Organizations. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duell, P.; Wright, D.; Renzaho, A.M.; Bhattacharya, D. Optimal health literacy measurement for the clinical setting: A systematic review. Patient Educ. Couns. 2015, 98, 1295–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Int. J. Surg. 2021, 88, 105906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, B.D.; Mays, M.Z.; Martz, W.; Castro, K.M.; DeWalt, D.A.; Pignone, M.P.; Mockbee, J.; Hale, F.A. Quick assessment of literacy in primary care: The newest vital sign. Ann. Fam. Med. 2005, 3, 514–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Abdulrazzaq, D.; Al-Taiar, A.; Al-Haddad, M.; Al-Tararwa, A.; Al-Zanati, N.; Al-Yousef, A.; Davidsson, L.; Al-Kandari, H. Cultural Adaptation of Health Literacy Measures: Translation Validation of the Newest Vital Sign in Arabic-Speaking Parents of Children with Type 1 Diabetes in Kuwait. Sci. Diabetes Self. Manag. Care 2021, 47, 164–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alberti, T.L.; Morris, N.J. Health literacy in the urgent care setting: What factors impact consumer comprehension of health information? J. Am. Assoc. Nurse Pract. 2017, 29, 242–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnekow, K.; Shyken, P.; Ito, J.; Deng, J.; Mohammad, S.; Fishbein, M. Magnetic Resonance Imaging: A Personalized Approach to Understanding Fatty Liver Disease. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2019, 68, 777–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belice, P.J.; Mosnaim, G.; Galant, S.; Kim, Y.; Shin, H.W.; Pires-Barracosa, N.; Hall, J.P.; Malik, R.; Becker, E. The impact of caregiver health literacy on healthcare outcomes for low income minority children with asthma. J. Asthma 2020, 57, 1316–1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brangan, S.; Ivanišić, M.; Rafaj, G.; Rowlands, G. Health literacy of hospital patients using a linguistically validated Croatian version of the Newest Vital Sign screening test (NVS-HR). PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0193079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpenter, C.R.; Kaphingst, K.A.; Goodman, M.S.; Lin, M.J.; Melson, A.T.; Griffey, R.T. Feasibility and diagnostic accuracy of brief health literacy and numeracy screening instruments in an urban emergency department. Acad. Emerg. Med. 2014, 21, 137–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro-Sánchez, E.; Vila-Candel, R.; Soriano-Vidal, F.J.; Navarro-Illana, E.; Díez-Domingo, J. Influence of health literacy on acceptance of influenza and pertussis vaccinations: A cross-sectional study among Spanish pregnant women. BMJ Open 2018, 8, e022132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, M., Jr.; Blucker, R.; Thompson, D.; Griffeth, E.; Grassi, M.; Damron, K.; Parrish, C.; Gillaspy, S.; Dunlap, M. Health Literacy Estimation of English and Spanish Language Caregivers. Health Lit. Res. Pract. 2018, 2, e107–e114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creary, S.; Adan, I.; Stanek, J.; O’Brien, S.H.; Chisolm, D.J.; Jeffries, T.; Zajo, K.; Varga, E. Sickle cell trait knowledge and health literacy in caregivers who receive in-person sickle cell trait education. Mol. Genet. Genomic Med. 2017, 5, 692–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escobedo, W.; Weismuller, P. Assessing health literacy in renal failure and kidney transplant patients. Prog. Transplant. 2013, 23, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esen, İ.; Aktürk Esen, S. Health Literacy and Quality of Life in Patients With Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus. Cureus 2020, 12, e10860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fleisher, J.E.; Shah, K.; Fitts, W.; Dahodwala, N.A. Associations and implications of low health literacy in Parkinson’s Disease. Mov. Disord. Clin. Pract. 2016, 3, 250–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griffey, R.T.; Melson, A.T.; Lin, M.J.; Carpenter, C.R.; Goodman, M.S.; Kaphingst, K.A. Does numeracy correlate with measures of health literacy in the emergency department? Acad. Emerg. Med. 2014, 21, 147–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassan, K.; Heptulla, R.A. Glycemic control in pediatric type 1 diabetes: Role of caregiver literacy. Pediatrics 2010, 125, e1104–e1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heberer, M.A.; Komenaka, I.K.; Nodora, J.N.; Hsu, C.H.; Gandhi, S.G.; Welch, L.E.; Bouton, M.E.; Aristizabal, P.; Weiss, B.D.; Martinez, M.E. Factors associated with cervical cancer screening in a safety net population. World J. Clin. Oncol. 2016, 7, 406–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, M.; Ren, D.; Gary-Webb, T.L.; Dunbar-Jacob, J.; Erlen, J.A. Characterizing a Sample of Chinese Patients with Type 2 Diabetes and Selected Health Outcomes. Diabetes Educ. 2019, 45, 105–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazley, A.S.; Hund, J.J.; Simpson, K.N.; Chavin, K.; Baliga, P. Health literacy and kidney transplant outcomes. Prog. Transplant. 2015, 25, 85–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lennerling, A.; Kisch, A.M.; Forsberg, A. Health literacy among swedish lung transplant recipients 1 to 5 years after transplantation. Prog. Transplant. 2018, 28, 338–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, J.B.; Peterson, P.N.; Dolansky, M.A.; Boxer, R.S. Health literacy and heart failure management in patient-caregiver dyads. J. Card. Fail. 2014, 20, 755–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maasdam, L.; Timman, R.; Cadogan, M.; Tielen, M.; van Buren, M.C.; Weimar, W.; Massey, E.K. Exploring health literacy and self-management after kidney transplantation: A prospective cohort study. Patient Educ. Couns. 2021, 105, 440–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mackley, A.; Winter, M.; Guillen, U.; Paul, D.A.; Locke, R. Health Literacy Among Parents of Newborn Infants. Adv. Neonatal. Care 2016, 16, 283–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGuinness, M.J.; Bucher, J.; Karz, J.; Pardee, C.; Patti, L.; Ohman-Strickland, P.; McCoy, J.V. Feasibility of Health Literacy Tools for Older Patients in the Emergency Department. West J. Emerg. Med. 2020, 21, 1270–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menendez, M.E.; Chen, N.C.; Mudgal, C.S.; Jupiter, J.B.; Ring, D. Physician Empathy as a Driver of Hand Surgery Patient Satisfaction. J. Hand Surg. Am. 2015, 40, 1860–1865.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menendez, M.E.; Mudgal, C.S.; Jupiter, J.B.; Ring, D. Health literacy in hand surgery patients: A cross-sectional survey. J. Hand Surg. 2015, 40, 798–804.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyers, N.; Glick, A.F.; Mendelsohn, A.L.; Parker, R.M.; Sanders, L.M.; Wolf, M.S.; Bailey, S.; Dreyer, B.P.; Velazquez, J.J.; Yin, H.S. Parents’ Use of Technologies for Health Management: A Health Literacy Perspective. Acad. Pediatr. 2020, 20, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, J.L.; Chung, M.L.; Etaee, F.; Hammash, M.; Thylen, I.; Biddle, M.J.; Elayi, S.C.; Czarapata, M.M.; McEvedy, S.; Cameron, J.; et al. Missed opportunities! End of life decision making and discussions in implantable cardioverter defibrillator recipients. Heart Lung 2019, 48, 313–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mock, M.S.; Sethares, K.A. Concurrent validity and acceptability of health literacy measures of adults hospitalized with heart failure. Appl. Nurs. Res. 2019, 46, 50–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, A.K.; Schapira, M.M.; Gorelick, M.H.; Hoffmann, R.G.; Brousseau, D.C. Low caregiver health literacy is associated with higher pediatric emergency department use and nonurgent visits. Acad. Pediatr. 2014, 14, 309–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, A.K.; Schapira, M.M.; Hoffmann, R.G.; Brousseau, D.C. Measuring health literacy in caregivers of children: A comparison of the newest vital sign and S-TOFHLA. Clin. Pediatr. 2014, 53, 1264–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Náfrádi, L.; Galimberti, E.; Nakamoto, K.; Schulz, P.J. Intentional and Unintentional Medication Non-Adherence in Hypertension: The Role of Health Literacy, Empowerment and Medication Beliefs. J. Public Health Res. 2016, 5, 762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oscalices, M.I.L.; Okuno, M.F.P.; Lopes, M.; Batista, R.E.A.; Campanharo, C.R.V. Health literacy and adherence to treatment of patients with heart failure. In Revista Da Escola De Enfermagem Da Usp; Universidade Federal de São Paulo: Santo Amaro, São Paulo, 2019; Volume 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palumbo, R.; Annarumma, C.; Adinolfi, P.; Musella, M. The missing link to patient engagement in Italy. J. Health Organ. Manag. 2016, 30, 1183–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, P.J.; Joel, S.; Rovena, G.; Pedireddy, S.; Saad, S.; Rachmale, R.; Shukla, M.; Deol, B.B.; Cardozo, L. Testing the utility of the newest vital sign (NVS) health literacy assessment tool in older African-American patients. Patient Educ. Couns. 2011, 85, 505–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pendlimari, R.; Holubar, S.D.; Hassinger, J.P.; Cima, R.R. Assessment of colon cancer literacy in screening colonoscopy patients: A validation study. J. Surg. Res. 2012, 175, 221–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodts, M.E.; Unaka, N.I.; Statile, C.J.; Madsen, N.L. Health literacy and caregiver understanding in the CHD population. Cardiol. Young 2020, 30, 1439–1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roh, Y.H.; Lee, B.K.; Park, M.H.; Noh, J.H.; Gong, H.S.; Baek, G.H. Effects of health literacy on treatment outcome and satisfaction in patients with mallet finger injury. J. Hand Ther. 2016, 29, 459–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenbaum, A.J.; Pauze, D.; Pauze, D.; Robak, N.; Zade, R.; Mulligan, M.; Uhl, R.L. Health Literacy in Patients Seeking Orthopaedic Care: Results of the Literacy in Musculoskeletal Problems (LIMP) Project. Iowa Orthop. J. 2015, 35, 187–192. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sheinis, M.; Bensimon, K.; Selk, A. Patients’ Knowledge of Prenatal Screening for Trisomy 21. J. Genet. Couns. 2018, 27, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singleton, I.M.; Garfinkel, R.J.; Malone, J.B.; Temkit, M.H.; Belthur, M.V. Determinants of caregiver satisfaction in pediatric orthopedics. J. Pediatr. Orthop. B 2021, 30, 393–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suka, M.; Odajima, T.; Okamoto, M.; Sumitani, M.; Igarashi, A.; Ishikawa, H.; Kusama, M.; Yamamoto, M.; Nakayama, T.; Sugimori, H. Relationship between health literacy, health information access, health behavior, and health status in Japanese people. Patient Educ. Couns. 2015, 98, 660–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valero-Chillerón, M.J.; González-Chordà, V.M.; Cervera-Gasch, Á.; Vila-Candel, R.; Soriano-Vidal, F.J.; Mena-Tudela, D. Health literacy and its relation to continuing with breastfeeding at six months post-partum in a sample of Spanish women. Nurs. Open 2021, 8, 3394–3402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wallace, A.S.; Perkhounkova, Y.; Bohr, N.L.; Chung, S.J. Readiness for Hospital Discharge, Health Literacy, and Social Living Status. Clin. Nurs. Res. 2016, 25, 494–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weinberg, J.A.; Shehada, M.Z.; Chapple, K.M.; Israr, S.; Jones, M.D.; Jacobs, J.V.; Bogert, J.N. The health literacy of hospitalized trauma patients: We should be screening for deficiencies. J. Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2019, 87, 1214–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wood, M.R.; Price, J.H.; Dake, J.A.; Telljohann, S.K.; Khuder, S.A. African American parents’/guardians’ health literacy and self-efficacy and their child’s level of asthma control. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2010, 25, 418–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yim, C.K.; Shumate, L.; Barnett, S.H.; Leitman, I.M. Health literacy assessment and patient satisfaction in surgical practice. Ann. Med. Surg. 2018, 35, 25–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, H.S.; Mendelsohn, A.L.; Fierman, A.; van Schaick, L.; Bazan, I.S.; Dreyer, B.P. Use of a pictographic diagram to decrease parent dosing errors with infant acetaminophen: A health literacy perspective. Acad. Pediatr. 2011, 11, 50–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Algabbani, A.M.; Alzahrani, K.A.; Sayed, S.K.; Alrasheed, M.; Sorani, D.; Almohammed, O.A.; Alqahtani, A.S. The impact of using pictorial aids in caregivers’ understanding of patient information leaflets of pediatric pain medications: A quasi-experimental study. Saudi. Pharm. J. 2022, 30, 544–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demir, N.; Koz, S.; Ugurlu, C.T. Health literacy in chronic kidney disease patients: Association with self-reported presence of acquaintance with kidney disease, disease burden and frequent contact with health care provider. Int. Urol. Nephrol. 2022, 54, 2295–2304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.H. Influences of decision preferences and health literacy on temporomandibular disorder treatment outcome. BMC Oral Health 2022, 22, 385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanu, C.; Brown, C.M.; Rascati, K.; Moczygemba, L.R.; Mackert, M.; Wilfong, L. General versus disease-specific health literacy in patients with breast cancer: A cross-sectional study. Support. Care Cancer 2022, 30, 5533–5538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorini, C.; Buscemi, P.; Mossello, E.; Schirripa, A.; Giammarco, B.; Rigon, L.; Albora, G.; Giorgetti, D.; Biamonte, M.A.; Fattorini, L.; et al. Health literacy of informal caregivers of older adults with dementia: Results from a cross-sectional study conducted in Florence (Italy). Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2023, 35, 61–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valero-Chilleron, M.J.; Mena-Tudela, D.; Cervera-Gasch, A.; Gonzalez-Chorda, V.M.; Soriano-Vidal, F.J.; Quesada, J.A.; Castro-Sanchez, E.; Vila-Candel, R. Influence of Health Literacy on Maintenance of Exclusive Breastfeeding at 6 Months Postpartum: A Multicentre Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 5411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baker, D.W.; Williams, M.V.; Parker, R.M.; Gazmararian, J.A.; Nurss, J. Development of a brief test to measure functional health literacy. Patient Educ. Couns. 1999, 38, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, P.; Callisaya, M.; Wills, K.; Greenaway, T.; Winzenberg, T. Cognition, educational attainment and diabetes distress predict poor health literacy in diabetes: A cross-sectional analysis of the SHELLED study. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0267265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abed, M.A.; Khalifeh, A.H.; Khalil, A.A.; Darawad, M.W.; Moser, D.K. Functional health literacy and caregiving burden among family caregivers of patients with end-stage renal disease. Res. Nurs. Health 2020, 43, 529–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alsomali, H.J.; Vines, D.L.; Stein, B.D.; Becker, E.A. Evaluating the Effectiveness of Written Dry Powder Inhaler Instructions and Health Literacy in Subjects Diagnosed with COPD. Respir. Care 2017, 62, 172–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carden, M.A.; Newlin, J.; Smith, W.; Sisler, I. Health literacy and disease-specific knowledge of caregivers for children with sickle cell disease. Pediatr. Hematol. Oncol. 2016, 33, 121–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, A.M.; Yehle, K.S.; Albert, N.M.; Ferraro, K.F.; Mason, H.L.; Murawski, M.M.; Plake, K.S. Health Literacy Influences Heart Failure Knowledge Attainment but Not Self-Efficacy for Self-Care or Adherence to Self-Care over Time. Nurs. Res. Pract. 2013, 2013, 353290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciampa, P.J.; White, R.O.; Perrin, E.M.; Yin, H.S.; Sanders, L.M.; Gayle, E.A.; Rothman, R.L. The association of acculturation and health literacy, numeracy and health-related skills in Spanish-speaking caregivers of young children. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2013, 15, 492–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Federman, A.D.; Wolf, M.S.; Sofianou, A.; Martynenko, M.; O’Connor, R.; Halm, E.A.; Leventhal, H.; Wisnivesky, J.P. Self-management behaviors in older adults with asthma: Associations with health literacy. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2014, 62, 872–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleisher, J.; Bhatia, R.; Margus, C.; Pruitt, A.; Dahodwala, N. Health literacy and medication awareness in outpatient neurology. Neurol. Clin. Pract. 2014, 4, 71–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goggins, K.M.; Wallston, K.A.; Nwosu, S.; Schildcrout, J.S.; Castel, L.; Kripalani, S. Health literacy, numeracy, and other characteristics associated with hospitalized patients’ preferences for involvement in decision making. J. Health Commun. 2014, 19 (Suppl. S2), 29–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guerra, C.E.; Dominguez, F.; Shea, J.A. Literacy and knowledge, attitudes, and behavior about colorectal cancer screening. J. Health Commun. 2005, 10, 651–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, V.; Shivaprakash, G.; Bhattacherjee, D.; Udupa, K.; Poojar, B.; Sori, R.; Mishra, S. Association of health literacy and cognition levels with severity of adverse drug reactions in cancer patients: A South Asian experience. Int. J. Clin. Pharm. 2020, 42, 1168–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirsh, J.M.; Boyle, D.J.; Collier, D.H.; Oxenfeld, A.J.; Caplan, L. Health literacy predicts the discrepancy between patient and provider global assessments of rheumatoid arthritis activity at a public urban rheumatology clinic. J. Rheumatol. 2010, 37, 961–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirsh, J.M.; Boyle, D.J.; Collier, D.H.; Oxenfeld, A.J.; Nash, A.; Quinzanos, I.; Caplan, L. Limited health literacy is a common finding in a public health hospital’s rheumatology clinic and is predictive of disease severity. J. Clin. Rheumatol. 2011, 17, 236–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iosifescu, A.; Halm, E.A.; McGinn, T.; Siu, A.L.; Federman, A.D. Beliefs about generic drugs among elderly adults in hospital-based primary care practices. Patient Educ. Couns. 2008, 73, 377–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivynian, S.E.; Ferguson, C.; Newton, P.J.; DiGiacomo, M. Factors influencing care-seeking delay or avoidance of heart failure management: A mixed-methods study. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2020, 108, 103603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehna, C.; McNeil, J. Mixed-methods exploration of parents’ health information understanding. Clin. Nurs. Res. 2008, 17, 133–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naik, A.D.; Street, R.L., Jr.; Castillo, D.; Abraham, N.S. Health literacy and decision making styles for complex antithrombotic therapy among older multimorbid adults. Patient Educ. Couns. 2011, 85, 499–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noureldin, M.; Plake, K.S.; Morrow, D.G.; Tu, W.; Wu, J.; Murray, M.D. Effect of health literacy on drug adherence in patients with heart failure. Pharmacotherapy 2012, 32, 819–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Conor, R.; Muellers, K.; Arvanitis, M.; Vicencio, D.P.; Wolf, M.S.; Wisnivesky, J.P.; Federman, A.D. Effects of health literacy and cognitive abilities on COPD self-management behaviors: A prospective cohort study. Respir. Med. 2019, 160, 105630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, C.; Kim, D.S.; Mika, V.H.; Ayaz, S.I.; Millis, S.R.; Dunne, R.; Levy, P.D. Emergency department visits in patients with low acuity conditions: Factors associated with resource utilization. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2018, 36, 1327–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinlan, P.; Price, K.O.; Magid, S.K.; Lyman, S.; Mandl, L.A.; Stone, P.W. The Relationship Among Health Literacy, Health Knowledge, and Adherence to Treatment in Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis. HSS J. 2013, 9, 42–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reisi, M.; Mostafavi, F.; Javadzede, H.; Mahaki, B.; Sharifirad, G.; Tavassoli, E. The Functional, Communicative, and Critical Health Literacy (FCCHL) Scales: Cross-Cultural Adaptation and the Psychometric Properties of the Iranian Version. Iran. Red. Crescent Med. J. 2017, 19, e29700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Sanders, L.M.; Thompson, V.T.; Wilkinson, J.D. Caregiver health literacy and the use of child health services. Pediatrics 2007, 119, e86–e92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, Y.H.; Pang, S.M.C.; Chan, M.F.; Yeung, G.S.P.; Yeung, V.T.F. Health literacy, complication awareness, and diabetic control in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J. Adv. Nurs. 2008, 62, 74–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallston, K.A.; Cawthon, C.; McNaughton, C.D.; Rothman, R.L.; Osborn, C.Y.; Kripalani, S. Psychometric properties of the brief health literacy screen in clinical practice. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2014, 29, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, R.O.; Chakkalakal, R.J.; Presley, C.A.; Bian, A.H.; Schildcrout, J.S.; Wallston, K.A.; Barto, S.; Kripalani, S.; Rothman, R. Perceptions of Provider Communication Among Vulnerable Patients with Diabetes: Influences of Medical Mistrust and Health Literacy. J. Health Commun. 2016, 21, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, R.O.; Osborn, C.Y.; Gebretsadik, T.; Kripalani, S.; Rothman, R.L. Health literacy, physician trust, and diabetes-related self-care activities in Hispanics with limited resources. J. Health Care Poor Underserved 2013, 24, 1756–1768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina, L.A.C.; Silva, R.A.; de Sousa Lima, M.M.; Barros, L.M.; Lopes, R.O.P.; Melo, G.A.A.; Garcia Lira Neto, J.C.; Caetano, J.A. Correlation Between Functional Health Literacy and Self-efficacy in People with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: Cross-sectional Study. Clin. Nurs. Res. 2022, 31, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osborne, R.H.; Batterham, R.W.; Elsworth, G.R.; Hawkins, M.; Buchbinder, R. The grounded psychometric development and initial validation of the Health Literacy Questionnaire (HLQ). BMC Public Health 2013, 13, 658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakker, M.M.; Putrik, P.; Rademakers, J.; van de Laar, M.; Vonkeman, H.; Kok, M.R.; Voorneveld-Nieuwenhuis, H.; Ramiro, S.; de Wit, M.; Buchbinder, R.; et al. Addressing Health Literacy Needs in Rheumatology: Which Patient Health Literacy Profiles Need the Attention of Health Professionals? Arthritis Care Res. 2021, 73, 100–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bourne, A.; Peerbux, S.; Jessup, R.; Staples, M.; Beauchamp, A.; Buchbinder, R. Health literacy profile of recently hospitalised patients in the private hospital setting: A cross sectional survey using the Health Literacy Questionnaire (HLQ). BMC Health Serv. Res. 2018, 18, 877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brorsen, E.; Rasmussen, T.D.; Ekstrøm, C.T.; Osborne, R.H.; Villadsen, S.F. Health literacy responsiveness: A cross-sectional study among pregnant women in Denmark. Scand. J. Public Health 2021, 50, 507–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.; Zheng, J.; Driessnack, M.; Liu, X.; Liu, J.; Liu, K.; Peng, J.; You, L. Health literacy as predictors of fluid management in people receiving hemodialysis in China: A structural equation modeling analysis. Patient Educ. Couns. 2021, 104, 1159–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cianfrocca, C.; Caponnetto, V.; Donati, D.; Lancia, L.; Tartaglini, D.; Di Stasio, E. The effects of a multidisciplinary education course on the burden, health literacy and needs of family caregivers. Appl. Nurs. Res. 2018, 44, 100–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahl, K.G.; Andersen, M.H.; Urstad, K.H.; Falk, R.S.; Engebretsen, E.; Wahl, A.K. Identifying Core Variables Associated With Health Literacy in Kidney Transplant Recipients. Prog. Transplant. 2020, 30, 38–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawson, J.; Hoffman, A.; Josland, E.; Smyth, A.; Brennan, F.; Brown, M. Evaluation of health literacy in end-stage kidney disease using a multi-dimensional tool. Ren. Soc. Australas. J. 2020, 16, 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinh, H.T.T.; Nguyen, N.T.; Bonner, A. Health literacy profiles of adults with multiple chronic diseases: A cross-sectional study using the Health Literacy Questionnaire. Nurs. Health Sci. 2020, 22, 1153–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodson, S.; Osicka, T.; Huang, L.; McMahon, L.P.; Roberts, M.A. Multifaceted Assessment of Health Literacy in People Receiving Dialysis: Associations With Psychological Stress and Quality of Life. J. Health Commun. 2016, 21, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freundlich Grydgaard, M.; Bager, P. Health literacy levels in outpatients with liver cirrhosis. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 2018, 53, 1584–1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hawkins, M.; Gill, S.D.; Batterham, R.; Elsworth, G.R.; Osborne, R.H. The Health Literacy Questionnaire (HLQ) at the patient-clinician interface: A qualitative study of what patients and clinicians mean by their HLQ scores. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2017, 17, 309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, L.Y.; Lin, Y.P.; Glass, G.F.; Chan, E.Y. Health literacy and patient activation among adults with chronic diseases in Singapore: A cross-sectional study. Nurs. Open 2021, 8, 2857–2865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kayser, L.; Hansen-Nord, N.S.; Osborne, R.H.; Tjønneland, A.; Hansen, R.D. Responses and relationship dynamics of men and their spouses during active surveillance for prostate cancer: Health literacy as an inquiry framework. BMC Public Health 2015, 15, 741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knudsen, M.V.; Petersen, A.K.; Angel, S.; Hjortdal, V.E.; Maindal, H.T.; Laustsen, S. Tele-rehabilitation and hospital-based cardiac rehabilitation are comparable in increasing patient activation and health literacy: A pilot study. Eur. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2020, 19, 376–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larsen, M.H.; Strumse, Y.S.; Andersen, M.H.; Borge, C.R.; Wahl, A.K. Associations between disease education, self-management support, and health literacy in psoriasis. J. Dermatol. Treat. 2021, 32, 603–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosallanezhad, Z.; Poornowrooz, N.; Javadpour, S.; Haghbeen, M.; Jamali, S. Health Literacy and its Relationship with Quality of Life in Postmenopausal Women. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2019, 13, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murali, K.; Mullan, J.; Roodenrys, S.; Lonergan, M. Comparison of health literacy profile of patients with end-stage kidney disease on dialysis versus non-dialysis chronic kidney disease and the influencing factors: A cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e041404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinderup, T.; Bager, P. Health literacy and liver cirrhosis: Testing three screening tools for face validity. Br. J. Nurs. 2019, 28, 441–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stømer, U.E.; Gøransson, L.G.; Wahl, A.K.; Urstad, K.H. A cross-sectional study of health literacy in patients with chronic kidney disease: Associations with demographic and clinical variables. Nurs. Open 2019, 6, 1481–1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stomer, U.E.; Wahl, A.K.; Goransson, L.G.; Urstad, K.H. Health literacy in kidney disease: Associations with quality of life and adherence. J. Ren. Care 2020, 46, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villadsen, S.F.; Hadi, H.; Ismail, I.; Osborne, R.H.; Ekstrøm, C.T.; Kayser, L. ehealth literacy and health literacy among immigrants and their descendants compared with women of Danish origin: A cross-sectional study using a multidimensional approach among pregnant women. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e037076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahl, A.K.; Hermansen, Å.; Osborne, R.H.; Larsen, M.H. A validation study of the Norwegian version of the Health Literacy Questionnaire: A robust nine-dimension factor model. Scand. J. Public Health 2021, 49, 471–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyer, A.; Begin, Y.; Dupont, J.; Rousseau-Gagnon, M.; Fernandez, N.; Demian, M.; Simonyan, D.; Agharazii, M.; Mac-Way, F. Health literacy level in a various nephrology population from Quebec: Predialysis clinic, in-centre hemodialysis and home dialysis; a transversal monocentric observational study. BMC Nephrol. 2021, 22, 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinh, H.T.T.; Nguyen, N.T.; Bonner, A. Healthcare systems and professionals are key to improving health literacy in chronic kidney disease. J. Ren. Care 2021, 48, 4–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Høeg, B.L.; Frederiksen, M.H.; Andersen, E.A.W.; Saltbæk, L.; Friberg, A.S.; Karlsen, R.V.; Dalton, S.O.; Horsbøl, T.O.; Bidstrup, P.E. Is the health literacy of informal caregivers associated with the psychological outcomes of breast cancer survivors? J. Cancer Surviv. 2020, 15, 729–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaps, L.; Omogbehin, L.; Hildebrand, K.; Gairing, S.J.; Schleicher, E.M.; Moehler, M.; Rahman, F.; Schattenberg, J.M.; Wörns, M.-A.; Galle, P.R.; et al. Health literacy in gastrointestinal diseases: A comparative analysis between patients with liver cirrhosis, inflammatory bowel disease and gastrointestinal cancer. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 21072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaps, L.; Hildebrand, K.; Nagel, M.; Michel, M.; Kremer, W.M.; Hilscher, M.; Galle, P.R.; Schattenberg, J.M.; Wörns, M.-A.; Labenz, C. Risk factors for poorer health literacy in patients with liver cirrhosis. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0255349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gurmu Dugasa, Y. Level of Patient Health Literacy and Associated Factors Among Adult Admitted Patients at Public Hospitals of West Shoa Oromia, Ethiopia. Patient Prefer. Adherence 2022, 16, 853–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tilahun, D.; Abera, A.; Nemera, G. Communicative health literacy in patients with non-communicable diseases in Ethiopia: A cross-sectional study. Trop. Med. Health 2021, 49, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, M.M.; Putrik, P.; Dikovec, C.; Rademakers, J.; E Vonkeman, H.; Kok, M.R.; Voorneveld-Nieuwenhuis, H.; Ramiro, S.; de Wit, M.; Buchbinder, R.; et al. Exploring discordance between Health Literacy Questionnaire scores of people with RMDs and assessment by treating health professionals. Rheumatology 2022, 62, 52–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chew, L.D.; Bradley Ka Fau—Boyko, E.J.; Boyko, E.J. Brief questions to identify patients with inadequate health literacy. Fam. Med. 2004, 36, 588–594. [Google Scholar]

- Albert, N.M.; Dinesen, B.; Spindler, H.; Southard, J.; Bena, J.F.; Catz, S.; Kim, T.Y.; Nielsen, G.; Tong, K.; Nesbitt, T.S. Factors associated with telemonitoring use among patients with chronic heart failure. J. Telemed. Telecare 2017, 23, 283–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacon, O.; Vandenberg, A.; May, M.E. Provider and patient perception of psychiatry patient health literacy. Pharm. Pract. (Granada) 2017, 15, 908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyle, J.; Speroff, T.; Worley, K.; Cao, A.; Goggins, K.; Dittus, R.S.; Kripalani, S. Low Health Literacy Is Associated with Increased Transitional Care Needs in Hospitalized Patients. J. Hosp. Med. 2017, 12, 918–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cawthon, C.; Mion, L.C.; Willens, D.E.; Roumie, C.L.; Kripalani, S. Implementing routine health literacy assessment in hospital and primary care patients. Jt. Comm. J. Qual. Patient Saf. 2014, 40, 68–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohn, J.A.; Shah, A.S.; Goggins, K.M.; Simmons, S.F.; Kripalani, S.; Dmochowski, R.R.; Schnelle, J.F.; Reynolds, W.S. Health literacy, cognition, and urinary incontinence among geriatric inpatients discharged to skilled nursing facilities. Neurourol. Urodyn. 2018, 37, 854–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cronin, R.M.; Hankins, J.S.; Byrd, J.; Pernell, B.M.; Kassim, A.; Adams-Graves, P.; Thompson, A.A.; Kalinyak, K.; DeBaun, M.R.; Treadwell, M. Modifying factors of the health belief model associated with missed clinic appointments among individuals with sickle cell disease. Hematology 2018, 23, 683–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cronin, R.M.; Yang, M.S.; Hankins, J.S.; Byrd, J.; Pernell, B.M.; Kassim, A.; Adams-Graves, P.; Thompson, A.A.; Kalinyak, K.; DeBaun, M.; et al. Association between hospital admissions and healthcare provider communication for individuals with sickle cell disease. Hematology 2020, 25, 229–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goggins, K.; Wallston, K.A.; Mion, L.; Cawthon, C.; Kripalani, S. What Patient Characteristics Influence Nurses’ Assessment of Health Literacy? J. Health Commun. 2016, 21, 105–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hillyer, G.C.; Park, Y.A.; Rosenberg, T.H.; Mundi, P.; Patel, I.; Bates, S.E. Positive attitudes toward clinical trials among military veterans leaves unanswered questions about poor trial accrual. Semin. Oncol. 2021, 48, 130–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inglehart, R.C.; Taberna, M.; Pickard, R.K.; Hoff, M.; Fakhry, C.; Ozer, E.; Katz, M.; Gillison, M.L. HPV knowledge gaps and information seeking by oral cancer patients. Oral Oncol. 2016, 63, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jo, A.; Ji Seo, E.; Son, Y.J. The roles of health literacy and social support in improving adherence to self-care behaviours among older adults with heart failure. Nurs. Open 2020, 7, 2039–2046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joyce, D.D.; Heslop, D.L.; Umoh, J.I.; Brown, S.D.; Robles, J.A.; Wallston, K.A.; Moses, K.A. Examining the association of health literacy and numeracy with prostate-related knowledge and prostate cancer treatment regret. Urol. Oncol. Semin. Orig. Investig. 2020, 38, 682.e11–682.e19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katz, P.; Dall’Era, M.; Trupin, L.; Rush, S.; Murphy, L.B.; Lanata, C.; Criswell, L.A.; Yazdany, J. Impact of Limited Health Literacy on Patient-Reported Outcomes in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Arthritis Care Res. (Hoboken) 2021, 73, 110–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, X.; Wang, M.; Zuo, Y.; Li, M.; Lin, X.; Zhu, S.; Zheng, Y.; Yu, M.; Lamoureux, E.L. Health literacy, computer skills and quality of patient-physician communication in Chinese patients with cataract. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e107615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNaughton, C.D.; Cawthon, C.; Kripalani, S.; Liu, D.; Storrow, A.B.; Roumie, C.L. Health literacy and mortality: A cohort study of patients hospitalized for acute heart failure. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2015, 4, e001799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munkhtogoo, D.; Nansalmaa, E.; Chung, K.P. The relationships of health literacy, preferred involvement, and patient activation with perceived involvement in care among Mongolian patients with breast and cervical cancer. Patient Educ. Couns. 2021, 105, 158–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrin, A.; Do Prado, L.S.; Duché, A.; Schott, A.M.; Dima, A.L.; Haesebaert, J. Using the brief health literacy screen in chronic care in french hospital settings: Content validity of patient and healthcare professional reports. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayan-Gharra, N.; Tadmor, B.; Balicer, R.D.; Shadmi, E. Multicultural Transitions: Caregiver Presence and Language-Concordance at Discharge. Int. J. Integr. Care 2018, 18, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, Y.J.; Shim, D.K.; Seo, E.K.; Seo, E.J. Health Literacy but Not Frailty Predict Self-Care Behaviors in Patients with Heart Failure. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Son, Y.J.; Won, M.H. Gender differences in the impact of health literacy on hospital readmission among older heart failure patients: A prospective cohort study. J. Adv. Nurs. 2020, 76, 1345–1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wright, J.P.; Edwards, G.C.; Goggins, K.; Tiwari, V.; Maiga, A.; Moses, K.; Kripalani, S.; Idrees, K. Association of Health Literacy With Postoperative Outcomes in Patients Undergoing Major Abdominal Surgery. JAMA Surg. 2018, 153, 137–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]